Abstract

Background

A thorough understanding of gastric cancer at the molecular level is urgently needed. One prominent oncogenic microRNA, miR-21, was previously reported to be upregulated in gastric cancer.

Methods

We performed an unbiased search for downstream messenger RNA targets of miR-21, based on miR-21 dysregulation, by using human tissue specimens and the MKN-28 human gastric carcinoma cell line. Molecular techniques include microRNA microarrays, cDNA microarrays, qRT-PCR for miR and mRNA expression, transfection of MKN-28 with miR-21 inhibitor or Serpini1 followed by Western blotting, cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry and luciferase reporter assay.

Results

This search identified Serpini1 as a putative miR-21 target. Luciferase assays demonstrated direct interaction between miR-21 and Serpini1 3’UTR. MiR-21 and Serpini1 expression levels were inversely correlated in a subgroup of gastric cancers, suggesting a regulatory mechanism that included both of these molecules. Furthermore, Serpini1 induced growth retardation of MKN28 and induced vigorous G1/S arrest suggesting its potential tumour-suppressive function in the stomach.

Conclusion

Taken together, these data suggest that in a subgroup of gastric cancers, miR-21 is upregulated, inducing downregulation of Serpini1, which in turn releases the G1-S transition checkpoint, with the end result being increased tumour growth.

Keywords: microRNA-21, Serpini1 gene, gastric cancer

INTRODUCTION

The worldwide incidence of gastric cancer (GC) is second only to lung cancer, with an estimated 850,000 newly diagnosed cases and 650,000 deaths occurring per year 1. The 5-year overall survival of resectable GC in specialized centres in Europe or the United States is only approximately 35% 2. Basic research investigating GC over the past two decades has yielded a multitude of findings. Although there is still no single molecular event or biomarker that can accurately predict GC development, behaviour, prognosis, or response to treatment, significant progress has been made in this context. For example, mutations in tumour suppressor genes, microsatellite instability, and DNA hypermethylation have all been shown to occur with regularity during the genesis and progression of this cancer 3–16. In addition, alterations in global gene expression patterns 17 or in the expression of individual tumour-related genes 18–21 have been reported in gastric neoplasia. More specifically, mutations in k-Ras were found to predict a 3-fold increase in the risk of malignant progression in patients with atrophic gastritis 22. Cancer invasiveness appears to correlate with DNA ploidy and the expression of p53 23. Microsatellite instability is also involved in gastric carcinogenesis 24–26. A deeper understanding of these molecular events and mechanisms in gastric carcinogenesis, along with their timing during this process, could lead to novel early detection and risk stratification biomarkers, as well as ultimately to novel therapeutic approaches to this common and deadly disease.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are a new class of small non-coding RNAs 27 that are 18–25 nucleotides in length 28. After synthesis, nascent miRs associate with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which in turn binds to mRNA 29. According to some bioinformatics estimates, miRs may regulate up to 30% of human genes 30. miRs are involved in a myriad of cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and response to stress 29. The functional effects of miRs are mediated by their binding to target mRNAs and consist of 2 types: 1) miR-bound mRNA is not translated, resulting in decreased production of protein; or 2) miR-bound mRNA is directly degraded, resulting in fewer transcript copies 29. However, new data suggest that miRs act primarily by decreasing the amount of mRNA 31. These data demonstrated that approximately 84% of miR-mediated effects on proteins are attributable to decreased corresponding mRNA levels, suggesting that quantifying miR effects at the mRNA level is a valuable approach to identifying miR targets.

Cancer-specific miR fingerprints have been identified in every type of tumour analyzed, including B-CLL 32, breast carcinoma 33, hepatocellular carcinoma 34, lung cancer 35, 36, and colon carcinoma 37. To date, several miRs have been identified as tumour-related, such as cluster miR-15a-16 38, cluster miR-143-145 33, the let-7 family 35, miR-21 33, miR-155 33, and the miR-17-19b cluster 39.

Among miRs previously reported to be dysregulated in specific cancer types, miR-21 is one of the most widely overexpressed in a variety of solid tumours, including GC 40, 44. Additional work further linked miR-21 to GC and Zhang et al. suggested that gastric mucosal infection with Helicobacter pylori, a known causative agent of GC, stimulates miR-21 expression 41. Furthermore, miR-21 resulted in increased GC cell proliferation 41. Nonetheless, the downstream effectors of miR-21 in GC continue to prove elusive, and thus further research is required to fully understand its effects in this malignancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human tissues

The tissue specimens were obtained at surgery performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland and Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania, after written informed patient consent was obtained. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for all cases included in the study. Human tissue was flash frozen immediately after removal from the patient and collection of relevant material for pathological diagnosis. Our tissue bank contained 51 pairs of gastric cancer and their matched normal stomach, for a total of 102 specimens. However, following RNA extraction, only 79 tissues demonstrated good quality RNA and were used for all subsequent studies. These 79 tissues included 28 pairs of matched gastric cancer and normal stomach (total of 56 specimens), 12 gastric cancer specimens with no matched normal stomach and 11 normal stomach specimens with no matched gastric cancer.

Cell lines

The present study used MKN-28 human gastric carcinoma cell line generously provided by Dr. Yutaka Shimada, Kyoto University. The cell line identity was checked by STR profile and compared with the original MKN-28 STR profile from The Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics. Cell passage and culture was carried out as previously described 42.

DNA and RNA extraction

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), as previously described 43.

MicroRNA arrays

100 ng of total RNA per specimen was used for miR arrays. We employed an Agilent Human miR array chip (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) containing 15.000 probes corresponding to 470 unique human miRs. Data was extracted using Feature Extraction Software 9.3 and GeneSpring software (Agilent). Raw array values below 5 were considered at or below background level. Array data was normalized to the 75th percentile, as previously described 43. The data was deposited on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

cDNA microarrays and filtering genes

The Illumina cDNA microarray platform was used for cDNA microarrays. Cells were treated with miR-21 mimic, inhibitor and non-specific, respectively, and 72 hours later were harvested and the RNA was extracted. The arrays were performed at the Johns Hopkins Bayview genomics core facility, as per the manufacturer protocol.

Transfection of miR-21 inhibitor

Synthesized RNA duplexes of miR-21 inhibitor were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). 30–50% confluent cells were transfected with 60 nM of miR-21 inhibitor or inhibitor negative control using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (Invitrogen). RNA and proteins were harvested 72 hours after transfection.

Transfection of MKN-28 cells with Serpini-1

MKN-28 cells were transfected with pCMV-XL5-Serpini-1 (Origene Technologies, Lafayette, CO, USA). As control group we used pCMV-XL5-empty plasmid. The transfection was performed by using Lipofectamine 2000 and proteins were extracted 3 days later.

Quantitative qRT-PCR (qRT-PCR) for miR and mRNA expression

We performed miR qRP-PCR to confirm the expression of miR-21 and mRNA of Serpini1. TaqMan MiR Assays (Human Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were used. Cycle passing threshold (Ct) was recorded and normalized to RNU6B expression. Relative expression was calculated as 2Ct_miR-21-Ct_RNU6B. PCR reactions were carried out in duplicate. All mRNA qRT-PCR values were normalized to beta-actin and the relative expression was calculated as 2Ct_target gene-Ct_beta-actin. PCR reactions were carried out in duplicate.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor complete EDTA-free (Roche). Protein concentration was measured using BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, MA, USA). Cell lysates (50 µg) were electrophoresed on 10–20% polyacrylamide gells (Bio-Rad) and transferred to Immobilon-PSQ membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with TBS containing 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween-20, then incubated with the primary antibody. Antibody to Serpini-1 was purchased from Abcam (ab46761). The membranes were incubated after washing with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ, USA) and analyzed using enhanced chemiluminescence-plus reagent (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Densitometry was performed on the western blot images by using the J-Image software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Cell counting

Ten thousand cells were plated in 24-well plates (Day 0), transfected after 24 hours and counted at days 1, 6 and 9 by using a hemocytometer and an inverted-light microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Staining was performed on gastric tissue microarrays by using an Envision kit (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). The specimens were stained with an antibody to Serpini1 purchased from Abcam (ab16171-100).

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis of DNA content was performed to assess cell cycle phase distribution. After transfection of Serpini1 at day 0, cells were harvested at day 3 and incubated with PI staining buffer (PBS 0.1 mg/mL PI, 0.6% NP40, 2 mg/mL Rnase A for 30 minutes on ice) (Roche Diagnostics). The DNA content was analyzed using FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, SAN Jose, CA, USA) and Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences) for histogram analysis. Nocodazole treatment, where applicable, was performed 24 hours prior to harvesting cells at a final concentration of 100 ng/mL. Attached cells and cells in the medium were collected and processed as above.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

A truncated fragment of Serpini1 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) containing the miR-21 predicted binding site was amplified from genomic DNA using linker primers containing XbaI restriction sites. Amplicons were cut by XbaI and cloned into an XbaI site just downstream of the firefly luciferase structural gene into vector pGL3 (Promega, Madison, WI). After ligation, we obtained plasmid clones containing the correct orientation (forward) insert (Serpini1 Fw). In addition, we have constructed plasmid clones with the 3’UTR of Serpini1 in reverse orientation (Serpini1 Rv). We also constructed separate plasmids containing Serpini1-3′UTR with mutated seed region for the predicted miR-21 binding site as negative controls. Eight thousand cells per well were seeded onto 96-well plates on the day prior to transfection, then transfected with miR-21 inhibitor and negative control, as described above. The constructed pGL3 vector and an internal control pRL-CMV (Renilla luciferase) vector (Promega, Madison, WI) were co-transfected 24 h after miR inhibitor transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). 24 hours after plasmid vector transfection, the luciferase reporter assay was performed using a Dual-Glo luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Luminescence intensity was measured by VICTOR2 fluorometry (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), and the luminescence intensity of Firefly luciferase was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase. Each treatment condition was performed in four replicates.

RESULTS

MicroRNA-21 expression in gastric cancer compared to normal stomach

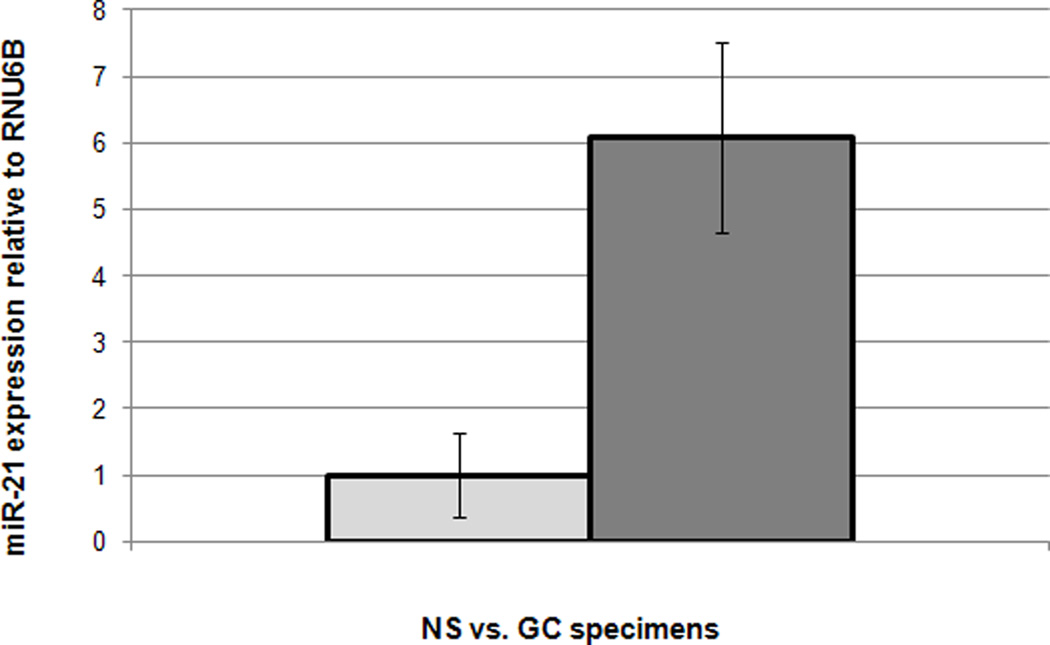

Prior to publications by other groups using miR microarrays in GC, we had already performed miR array hybridizations on 3 NS and 7 GC specimens. Raw data was 75th percentile normalized and subsequent analyses using Significance Analysis of Microarrays revealed that miR-21 was upregulated in GC vs. normal stomach (NS, p-value < 0.01, unpaired Student’s T test, Figure 1). These data are in accord with other published reports regarding upregulation of miR-21 in GC 44. Next, we sought to verify array data using quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) on a larger cohort of 79 gastric tissues, including 40 NS and 39 GC specimens. The cohort of 79 specimens included 28 pairs of matched gastric cancers and normal stomach (total number of 56 tissues). Supplementary Figure 1 displays the expression of miR-21 in these matched specimens. The p-value of the difference in miR-21 levels between matched gastric cancers and normal tissues was 0.02 (paired Student’s t-test). When analyzing the expression of miR-21 in the whole cohort of 79 tissues, miR-21 was found to be upregulated 1.8-fold in GCs vs. NSs (p-value < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t-test; Supplementary Figure 2), results which were also confirmed independently by another group 44.

Figure 1.

miR-21 is overexpressed in gastric cancer (GC) vs. normal stomach (NS) specimens. X-axis: specimens; Y-axis: microarray values for miR-21

Serpini1 as a target of miR-21

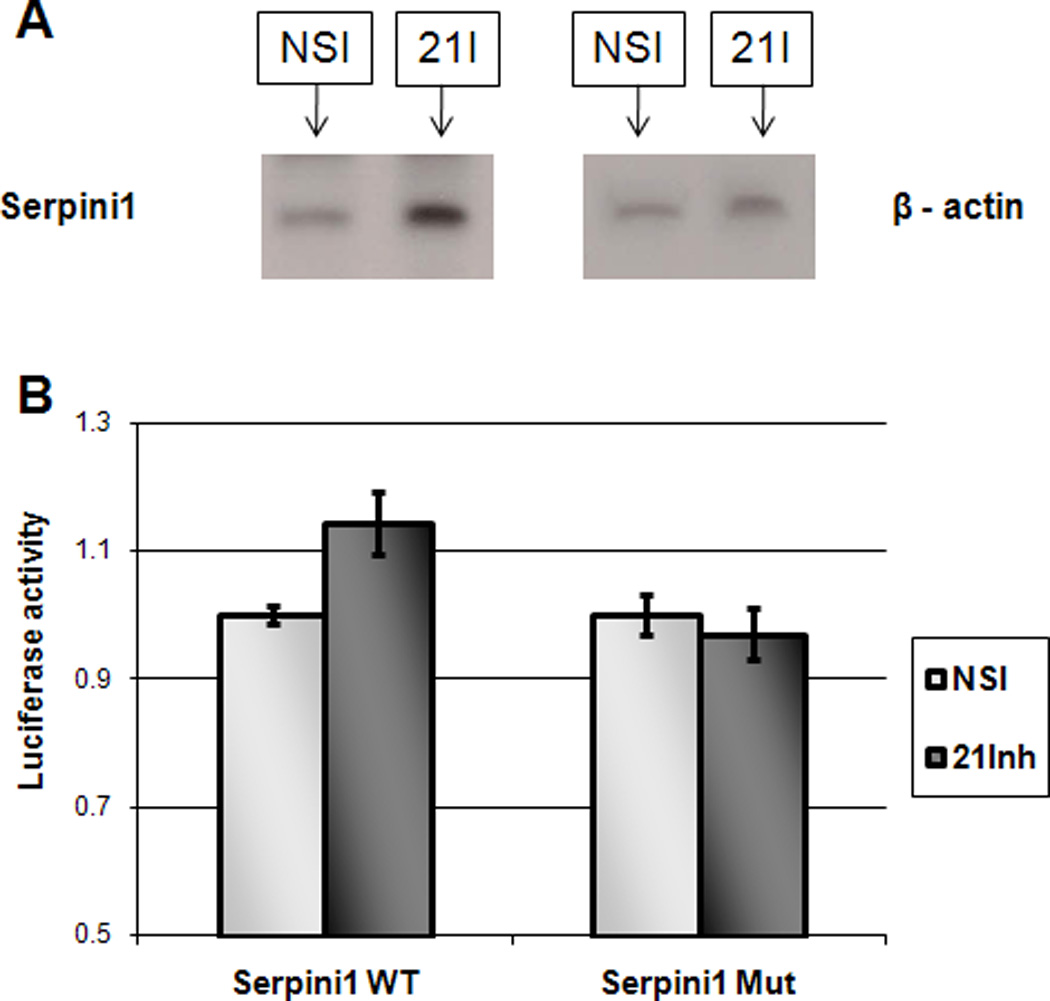

We sought to identify novel targets for miR-21 that could exert a biological impact on GC. To screen for potential targets in an unbiased fashion, we transfected MKN28 GC cells with a miR-21 inhibitor and with a non-specific inhibitor, respectively, then hybridized RNAs from these cells with mRNA arrays. Similarly, MKN28 cells were treated with a miR-21 mimic and a nonspecific mimic, followed by mRNA array hybridizations. Genes exhibiting raw expression values less than 35 were not further analyzed, since their expression was deemed to be too low. Next, we searched for genes whose expression levels increased upon inhibition of miR-21 and whose expression was decreased after treatment with a miR-21 mimic. This gene set was further reduced to mRNAs with putative miR-21 binding sites in their 3’UTRs. To increase specificity, we employed 2 search engines, (TargetScan and PicTar) for the in silico search for miR-21 targets. We further selected genes that demonstrated at least a 20% change in expression following miR-21 transfections. These filtering procedures reduced the candidate gene list to 22 (Table 1). MKN28 cells produce miR-21; thus, we deemed a gene to be more important if its expression was increased by miR-21 inhibition than if its expression was downregulated by miR-21 stimulation. Therefore, we ordered genes by their percent increase upon miR-21 inhibition. To further filter the gene list to identify a single suitable candidate for further study, we explored which proteins in Table 1 were known to be expressed in gastric tissues. Based on data available in the Protein Atlas (http://www.proteinatlas.org/), Serpini1 was the highest-ranked gene whose protein was expressed in normal gastric tissue as well as in gastric cancers. We therefore selected Serpini1 for further analyses. Next, we verified with RT-PCR that the mRNA level of Serpini1 increases upon miR-21 inhibition. Indeed, inhibiting miR-21 in MKN28 cells induced an increase of approximately 11% in the level of Serpini1 mRNA (Supplementary Figure 3). To verify that the expression of Serpini1 changed at the protein level in response to miR-21 manipulation, we performed Western blotting on cells treated with a miR-21 inhibitor. Figure 2A illustrates our finding that the Serpini1 protein levels increased upon miR-21 inhibition, in accord with mRNA data. The density of the NSI band was measured by employing ImageJ at 96 units, and the density of the 21I band was measured at 146 units, which represents an approximately 50% increase in protein level.

Table 1.

miR-21 impacts the expression of 22 genes.

| Probe ID | Symbol | Increase with miR-21Inh (%) | Decrease with miR-21Mim (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ILMN_1686116 | THBS1 | 76.38 | 51.37 |

| ILMN_2183216 | TTRAP | 71.65 | 50.67 |

| ILMN_2278512 | NFATC2IP | 64.34 | 55.30 |

| ILMN_1814333 | SERPINI1 | 58.02 | 22.46 |

| ILMN_2050654 | SAV1 | 46.67 | 35.97 |

| ILMN_1769040 | NCOA2 | 46.64 | 27.80 |

| ILMN_2366703 | SGK3 | 46.60 | 22.87 |

| ILMN_1774259 | FAM63B | 45.04 | 20.52 |

| ILMN_1722426 | OR7D2 | 42.59 | 21.76 |

| ILMN_2315964 | PSRC1 | 41.38 | 36.33 |

| ILMN_2052686 | LCA5 | 41.10 | 20.23 |

| ILMN_1720988 | ABI2 | 39.90 | 26.65 |

| ILMN_1659470 | PBRM1 | 37.08 | 31.19 |

| ILMN_1809607 | PPIF | 36.76 | 30.16 |

| ILMN_1744709 | DLG5 | 36.22 | 29.99 |

| ILMN_1668507 | DDAH1 | 35.62 | 48.80 |

| ILMN_2136423 | MARS2 | 35.33 | 24.49 |

| ILMN_2060145 | GRHL2 | 34.25 | 43.42 |

| ILMN_1786852 | ZCCHC3 | 32.99 | 24.74 |

| ILMN_2334350 | BTBD3 | 30.88 | 26.12 |

| ILMN_1737124 | PRPF4B | 30.88 | 23.29 |

| ILMN_1655577 | TIAM1 | 30.58 | 26.40 |

ProbeID – Illumina identifier; miR-21Inh – miR-21 inhibition; miR21-Mim – miR-21 stimulation. Genes are ordered base on the percent increase upon miR-21 inhibition.

Figure 2.

miR-21 modulates the expression of Serpini1 and directly interacts with Serpini1 3’UTR.

Panel A. Representative Western blot demonstrating increased protein level of Serpini1 following miR-21 inhibition (21-I in the figure). NSI – non specific inhibitor.

Panel B. MKN28 cells were transfected with a fragment of Serpini1 3’UTR (Serpini1 in the figure) or with a fragment of Serpini1 3’UTR with a mutated miR-21 binding site (Serpini1Mut in the figure), cloned downstream of the luciferase promoter. These cells were co-transfected with either miR-21 inhibitor (21Inh in the figure) or with a non-specific inhibitor (NSI in the figure). miR-21 inhibitor moderately increases the activity of the luciferase compared to the mutated control. Y-axis: arbitrary luminescence units. Standard errors are shown.

MiR-21 binding to Serpini1 3’UTR and effect on expression

MKN28 cells were transfected with a luciferase expressing plasmid containing a fragment of Serpini1 3’UTR that included a miR-21 binding site. Cells were also transfected with an expression plasmid containing the same Serpini1 3’UTR fragment, with a mutated miR-21 binding site, serving as a control. Figure 2B demonstrates that miR-21 inhibitor transfected cells demonstrated a moderate, but statistically significantly higher Serpini1 3’UTR luciferase activity (14.38%, p<0.05 Student’s T-test). Transfecting cells with the mutated 3’UTR plasmid demonstrated no effect of miR-21 inhibitor onto the luciferase activity, confirming the direct interaction between miR-21 and the 3’UTR of Serpini1 mRNA. To demonstrate that in the complete absence of miR-21 binding site, the luciferase expression is not changed, we devised a control vector that contains the Serpini1 3’UTR sequence in a reverse orientation (Serpini1 Rv), and then verified that in this orientation there is no binding site for miR-21. We used the reverse orientation of Serpini1 3’UTR so that the total length of the construct is the same as in the rest of the luciferase experiments. These experiments demonstrated that, in the absence of a miR-21 binding site, there is no difference between the luciferase intensity in cells treated with NSI (non specific inhibitor) and cells treated with miR-21 inhibitor (miR-21I, Supplementary Figure 4).

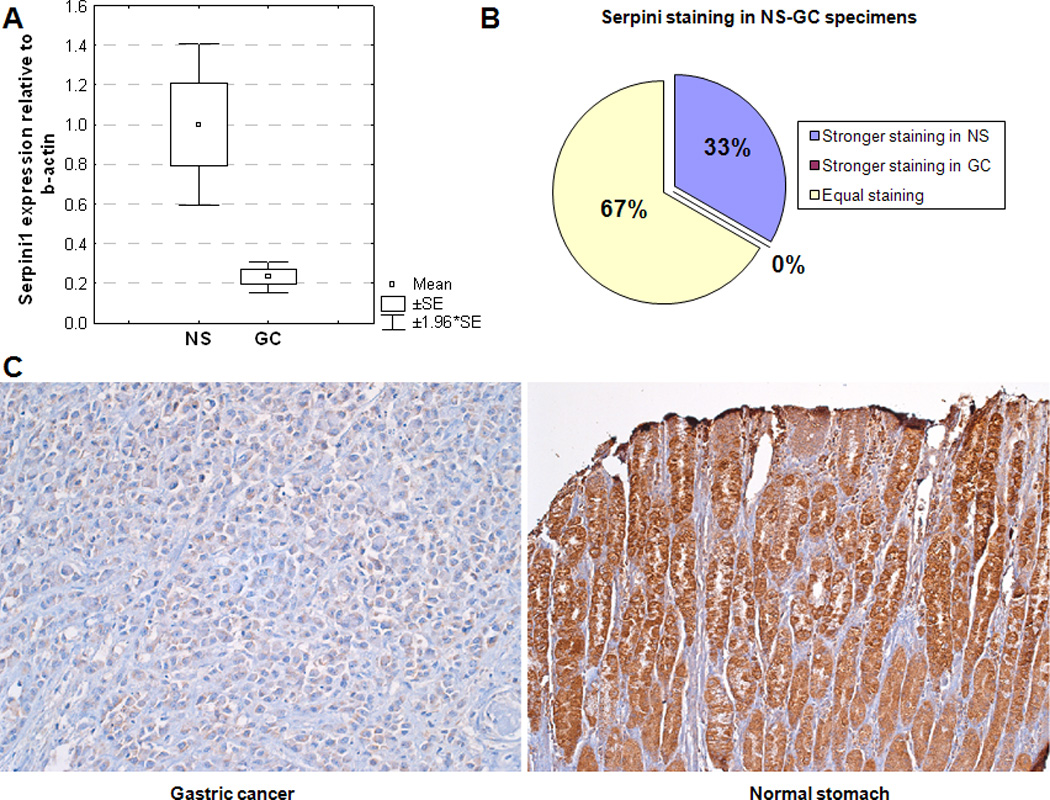

Serpini1 expression levels in human gastric cancer compared to normal stomach

mRNA and protein levels of Serpini1 appeared to be significantly modulated by miR-21. Since miR-21 was already known to be more highly expressed in GCs than NSs, we determined whether the levels of Serpini1 differed between GCs and NSs, by utilizing the whole cohort of 79 specimens. Figure 3A shows that Serpini1 mRNA levels were significantly lower in GCs than in NS specimens (p-value < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t-test). To obtain further information regarding protein levels of Serpini1 in human specimens, we performed immunohistochemical (IHC) staining with an anti-Serpini1 antibody on a human tissue microarray. This tissue microarray contained 36 paired specimens: 18 GCs and matching 18 NSs. The stained tissue microarray was read by a pathologist with expertise in gastrointestinal cancers. Staining intensity was scored from 0 to 9, with 0 connoting no staining and 9 signifying the most intense staining. A score of 0–4 was labeled as low-grade and 5–9 as high-grade staining. In comparing the 18 pairs in terms of their staining with Serpini1, 12 pairs displayed equal staining in GC and NS. However, 6 pairs displayed high-grade staining in NS but low-grade staining in GC. In addition, there were no pairs in which GC displayed higher staining than did matched NS (Figure 3B). These data suggest that a subgroup of GCs – approximately 33% - display decreased Serpini1 protein levels relative to NS. The difference in the expression level of Serpini1 mRNA and protein between GC and NS is, perhaps, secondary to other regulatory influences, outside of miR-21, exerted upon translating Serpini1 mRNA into protein. Although miR-21 appears to have a consistent and reproducible effect, other factors may influence the protein level of Serpini1. Taken together, the mRNA and protein data presented in Figure 3 suggest that Serpini1 tends to be expressed at lower levels in GCs than in NSs. Figure 3C displays representative staining from the tissue microarrays for 1 GC and 1 NS specimen, respectively.

Figure 3.

Serpini1 is expressed at lower levels in gastric cancer (GC) vs. normal stomach (NS).

Panel A. mRNA levels of Serpini1 are lower in GC than in NS. X-axis: specimens; Y-axis: mRNA level of Serpini1 relative to beta-actin.

Panel B. Approximately 2/3 of specimens demonstrated similar Serpini1 staining in GC and matched NS (green in the figure). Approximately 1/3 of specimens demonstrated stronger staining in NS than in matched GC (blue in the figure)

Panel C. Representative image of staining with Serpini1 antibody in GC and NS, demonstrating stronger staining in NS than in GC.

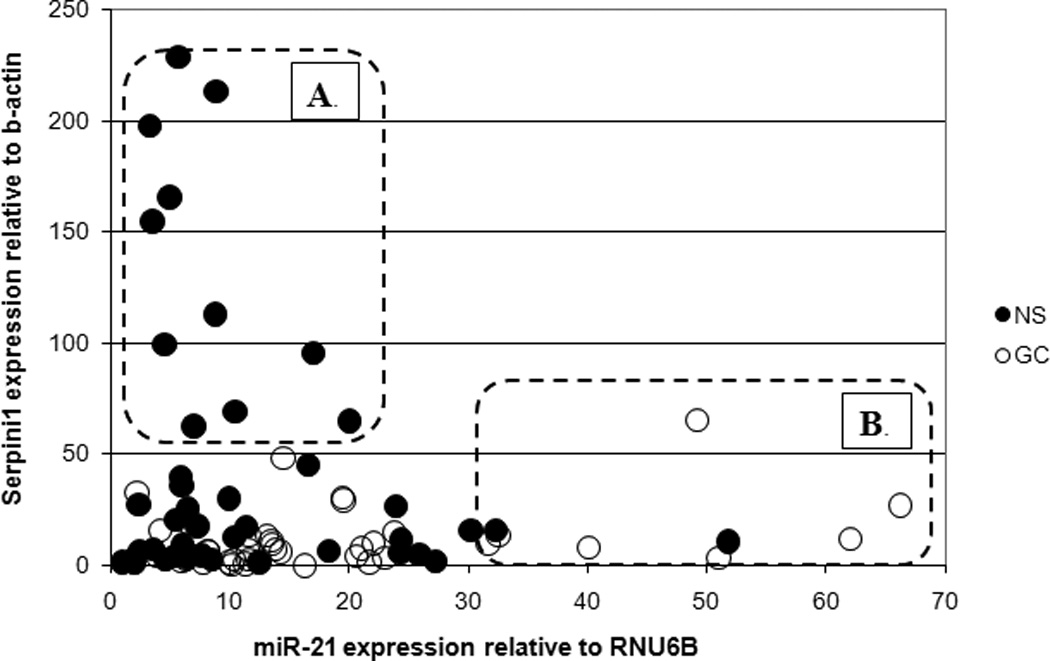

Correlation of MiR-21 levels with Serpini1 expression in human gastric specimens

We determined that miR-21 modulates the level of Serpini1 in gastric cells. To ascertain whether there was any correlation between miR-21 and Serpini1 levels in primary human gastric specimens, we performed qRT-PCRs for miR-21 and for Serpini1 on 28 pairs of matched human gastric specimens. Results of these experiments are displayed in Figure 4. Although the correlation between miR-21 and Serpini did not reach statistical significance for all 28 pairs, there was an inverse correlation between the expression levels of miR-21 and those of Serpini1 in a subgroup of NS and GC tissues. These findings suggest that, in at least some specimens, miR-21 and Serpini1 constitute participants in a unified signaling pathway. In addition, analogously to the IHC data, Figure 4 shows that there is a subgroup of NSs with low expression of Serpini1, suggesting that other tumour suppressor pathways are likely important in this latter subgroup.

Figure 4.

Serpini1 inversely correlates with miR-21 in a subgroup of gastric cancer and normal stomach specimens. X-axis: miR-21 expression relative to RNU6B; Y-axis: Serpini1 expression relative to beta-actin; NS, normal stomach (green in the figure); GC, gastric cancer (red in the figure). A subgroup of NS specimens (A in the figure) demonstrates low levels of miR-21 and high levels of Serpini1, suggestive of a functioning miR-21 – Serpini1 pathway. A subgroup of GC specimens (B in the figure) demonstrates high levels of miR-21 and low levels of Serpini1, suggestive of dysregulated miR-21 expression, impacting Serpini1 which in turn may induce faster cancer growth. The third group of specimens (all dots outside of A and B) demonstrate low levels of both Serpini1 and miR-21.

Serpini1 tumour-suppressive functions in gastric cancer cells

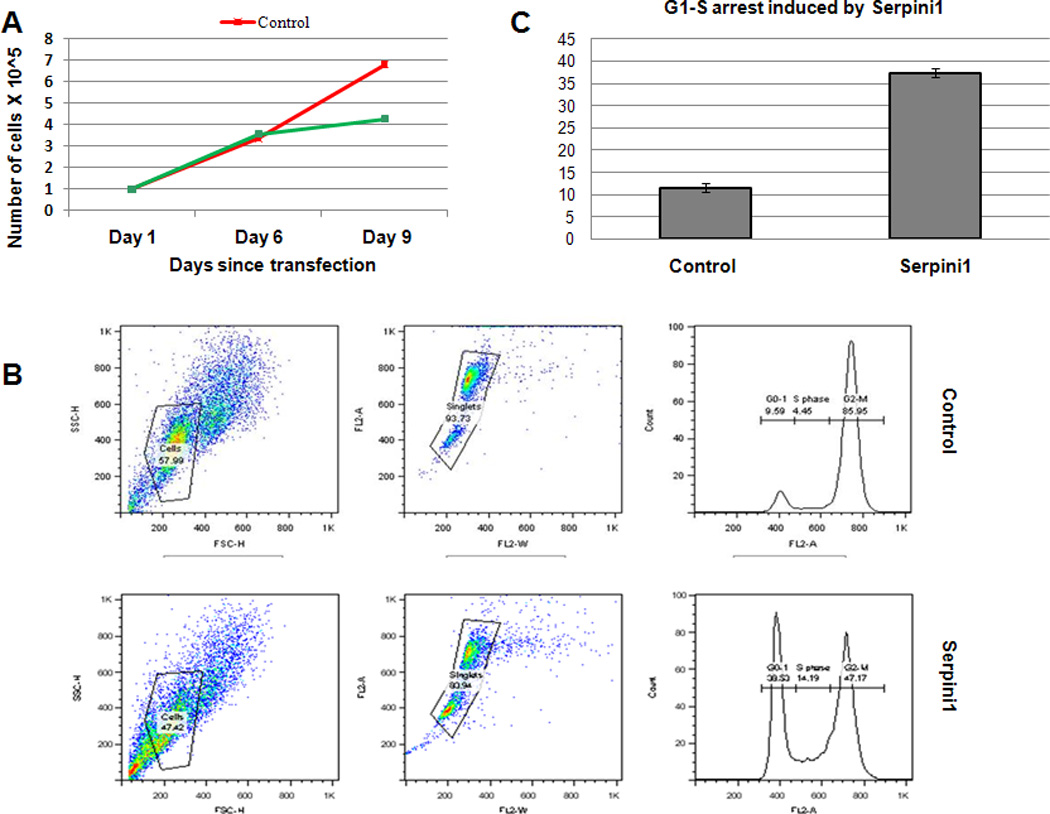

MiR-21 had previously been proven to exert tumour-promoting effects in human cancers, acting as a bona-fide oncogene or oncomiR 45. Since our data suggested that 1) miR-21 was elevated in GC and regulated Serpini1 in gastric tissues, and 2) Serpini1 was downregulated in GCs, we hypothesized that Serpini1 exerted tumour-suppressive effects in gastric cells. As Figure 5A shows, cells overexpressing Serpini1 grew slower than cells expressing only baseline (endogenous) Serpini1. These findings suggested that Serpini1 could exert a tumour-suppressive function in gastric cancer cells, and that miR-21 could be exerting at least part of its tumour-promoting actions via Serpini1 inhibition. Next, we sought to identify the mechanisms through which Serpini1 decreased the growth of gastric cancer cells. To this end, we performed cell cycle analyses on GC cells transfected with Serpini1 vs. a control vector. At baseline, there was no difference between cells transfected with Serpini1 vs. control in the percentage of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle. Nevertheless, upon synchronization of cancer cells with Nocodazole, Serpini1 induced reproducible and highly significant G1-S arrest (Figure 5B and C). These results suggest that G1/S arrest represents a mechanism thorough which Serpini1 suppresses GC cell growth.

Figure 5.

Serpini1 induces growth retardation in gastric cancer cells by reinforcing G1 to S transition checkpoint.

Panel A. X-axis: days since transfection; Y-axis: number of cells X 10^5. Cells treated with control (Red in the figure) continue to grow, while cells transfected with Serpini1 (Green in the figure) demonstrate grow retardation.

Panel B. Serpini1 induces a strong G1 arrest upon cell synchronization with Nocodazole.

Panel C. The results of 3 experiments done in triplicate are shown, with a statistically significantly increased in the proportion in G1 in cells transfected with Serpini1 (green in the figure) vs. cells treated with control. X-axis: control vs. Serpini1-transfected cells; Y-axis: proportion

DISCUSSION

Gastric cancer represents an important burden on human health, with hundreds of thousands of newly diagnosed cases as well as related deaths worldwide per year. Improved understanding of this deadly cancer at the basic molecular level is greatly needed. The current study provides insight into a potential novel regulatory mechanism involved in gastric carcinogenesis. Our data suggests that miR-21, which is known to be overexpressed in gastric cancer, downregulates Serpini1, which in turn releases cells from the G1-S transition checkpoint.

Our data shows that transfecting Serpini1 into MKN28 cells induces slower growth, however, these effects are not obvious until Day 6. A potential explanation is that MKN28 cells already express Serpini1 at baseline and adding Serpini1 may only mildly contribute to the growth arrest effects of Serpini1, at least in basal conditions. In accord with this hypothesis, as mentioned in the Cell Cycle section within Results, at baseline, transfecting Serpini1 into MKN28 cells does not induce G1 arrest. However, upon synchronization of cells with Nocodazole, which can be interpreted (due to its effects on the mitotic spindle) as a stressor on these cells, Serpini1 induces a vigorous G1 arrest, as demonstrated in Figure 5B and C. However, the growth curve in Figure 5A is performed with cells at baseline, and it is possible that the growth suppressive effects of Serpini1 are not obvious until cells reach a certain confluence, and become stressed either by the lack of nutrients or by paracrine signals secreted in the media by themselves.

MiR-21 was previously reported to be upregulated in a number of malignancies, including lymphoma, glioblastoma multiforme, osteosarcoma, cholangiocarcinoma and gastric cancer 41, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48. Our data confirmed its upregulation on a large cohort of GC vs. NS subjects. In addition, the fold difference in miR-21 levels between GCs and NSs in our study is similar to other reports 44. To understand the involvement of miR-21 in GC, in the current study, its downstream targets were searched for in an unbiased fashion, by employing mRNA arrays. This approach offers the benefit of performing an impartial and comprehensive search for downstream targets and is based on growing evidence suggesting that the majority of miR functions are exerted through mRNA downregulation, rather than by protein translation inhibition 31. This search identified as a putative miR-21 target the gene Serpini1, a previously unstudied gene in gastric cancer.

Serpini1, also known as neuroserpin, is an inhibitor of tissue plasminogen activator that is normally expressed during development and in the adult nervous systems 49. Serpini1 was also recently identified in myeloid lineage cells 50. Its expression is downregulated in glioblastomas and pheochromocytomas 49, but, to our knowledge, it has never been reported to be downregulated in gastric cancer. Our report also suggests, for the first time, that Serpini1 appears to play a tumour-suppressive role in GC.

The data presented herein strongly suggest that miR-21 and Serpini1 are inversely expressed in a subgroup of gastric cancers, suggesting a regulatory network that includes both of these molecules. Further work is needed to characterize this subgroup of gastric cancers, with the purpose of advancing current molecular taxonomies, as well as in pursuit of potential novel therapeutics based on the interaction between miR-21 and Serpini1. Discoveries regarding the role of microRNAs in cancer have pointed to a broad array of potential applications regarding diagnostics and prognostics. The current manuscript describes, to our knowledge for the first time, the involvement of microRNA-21 and its downstream target, Serpini-1, in gastric adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. miR-21 is expressed at higher levels in gastric cancer (GC) vs. matched normal stomach (NS) specimens. The X-axis displays the type of specimen (GC vs. NS). The Y-axis shows fold difference in miR-21 expression between every GC specimen and the matched NS specimen.

Supplementary Figure 2. miR-21 is overexpressed in gastric cancer (GC) vs. normal stomach (NS) specimens based on RT-PCR data obtained for 79 specimens. miR-21 was found to be upregulated in GC compared to NS specimens. X-axis: specimens; Y-axis: RT-PCR values for miR-21. The average expression of miR-21 in NS was normalized to 1. The error bars signify Standard Error of the Mean.

Supplementary Figure 3. The level of Serpini1 mRNA increases with miR-21 inhibition. MKN28 gastric cancer cells were transfected with NSI and 21I and RT-PCR was performed to detect the level of Serpini1 mRNA. The increase in the level of Serpini1 mRNA is in line with the luciferase experiments and RT-PCR results on human gastric specimens.

Supplementary Figure 4. Luciferase activity is the same when cells are transfected with a construct that does not include miR-21 binding site. MKN28 cells were transfected with Seripini1 Rv then with NSI or 21I. The figure demonstrates that the luciferase intensity is approximately the same (p-value 0.9, unpaired Student’s t-test) for NSI and 21I.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This work was supported by an American Gastroenterological Association grant to F.M.S. (Fellowship to Faculty Transition Award), by a Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute (FAMRI) grant (072119_YCSA) to F.M.S., by the Johns Hopkins Clinician Scientist Award to F.M.S., by a Pilot Project from the The Hopkins Conte Digestive Diseases Basic & Translational Research Core Center to F.M.S., and by a K08 Award (DK090154-01) from the NIH to F.M.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 46:765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi Y, Zhou Y. The role of surgery in the treatment of gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 101:687–692. doi: 10.1002/jso.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han HJ, Yanagisawa A, Kato Y, et al. Genetic instability in pancreatic cancer and poorly differentiated type of gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5087–5089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhyu MG, Park WS, Meltzer SJ. Microsatellite instability occurs frequently in human gastric carcinoma. Oncogene. 1994;9:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakashima H, Inoue H, Mori M, et al. Microsatellite instability in Japanese gastric cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:1503–1507. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950315)75:6+<1503::aid-cncr2820751520>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamura G, Sakata K, Maesawa C, et al. Microsatellite alterations in adenoma and differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1933–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmutte C, Baffa R, Veronese LM, et al. Human thymine-DNA glycosylase maps at chromosome 12q22-q24.1: a region of high loss of heterozygosity in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3010–3015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleisher AS, Esteller M, Wang S, et al. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter in human gastric cancers with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1090–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki H, Itoh F, Toyota M, et al. Distinct methylation pattern and microsatellite instability in sporadic gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:309–313. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991029)83:3<309::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto H, Perez-Piteira J, Yoshida T, et al. Gastric cancers of the microsatellite mutator phenotype display characteristic genetic and clinical features. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1348–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70499-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung SY, Yuen ST, Chung LP, et al. hMLH1 promoter methylation and lack of hMLH1 expression in sporadic gastric carcinomas with high-frequency microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 1999;59:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Suzuki H, et al. Aberrant methylation in gastric cancer associated with the CpG island methylator phenotype. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5438–5442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toyota M, Ho C, Ohe-Toyota M, et al. Inactivation of CACNA1G, a T-type calcium channel gene, by aberrant methylation of its 5' CpG island in human tumours. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4535–4541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuchiya T, Tamura G, Sato K, et al. Distinct methylation patterns of two APC gene promoters in normal and cancerous gastric epithelia. Oncogene. 2000;19:3642–3646. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura G, Yin J, Wang S, et al. E-Cadherin gene promoter hypermethylation in primary human gastric carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:569–573. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleisher AS, Esteller M, Tamura G, et al. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter is associated with microsatellite instability in early human gastric neoplasia. Oncogene. 2001;20:329–335. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hippo Y, Taniguchi H, Tsutsumi S, et al. Global gene expression analysis of gastric cancer by oligonucleotide microarrays. Cancer Res. 2002;62:233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsui S, Shiozaki H, Inoue M, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of alpha-catenin expression in human gastric cancer. Virchows Arch. 1994;424:375–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00190559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baffa R, Veronese ML, Santoro R, et al. Loss of FHIT expression in gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4708–4714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shun CT, Wu MS, Lin JT, et al. An immunohistochemical study of E-cadherin expression with correlations to clinicopathological features in gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:944–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takakura S, Kohno T, Manda R, et al. Genetic alterations and expression of the protein phosphatase 1 genes in human cancers. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:817–824. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong C, Mera R, Bravo JC, et al. KRAS mutations predict progression of preneoplastic gastric lesions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugai T, Nakamura S, Uesugi N, et al. Role of DNA aneuploidy, overexpression of p53 gene product, and cellular proliferation in the progression of gastric cancer. Cytometry. 1999;38:111–117. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990615)38:3<111::aid-cyto4>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semba S, Yokozaki H, Yasui W, et al. Frequent microsatellite instability and loss of heterozygosity in the region including BRCA1 (17q21) in young patients with gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 1998;12:1245–1251. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.6.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiao YH, Bovo D, Guido M, et al. Microsatellite instability and/or loss of heterozygosity in young gastric cancer patients in Italy. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:59–62. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990702)82:1<59::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mori Y, Sato F, Selaru FM, et al. Instabilotyping reveals unique mutational spectra in microsatellite-unstable gastric cancers. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3641–3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummins JM, Velculescu VE. Implications of micro-RNA profiling for cancer diagnosis. Oncogene. 2006;25:6220–6227. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Croce CM, Calin GA. miRNAs, cancer, and stem cell division. Cell. 2005;122:6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, et al. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calin GA, Liu CG, Sevignani C, et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11755–11760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404432101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu CG, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7065–7070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami Y, Yasuda T, Saigo K, et al. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA expression patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma and non-tumourous tissues. Oncogene. 2006;25:2537–2545. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K, et al. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3753–3756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michael MZ, SM OC, van Holst Pellekaan NG, et al. Reduced accumulation of specific microRNAs in colorectal neoplasia. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumours defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z, Li Z, Gao C, et al. miR-21 plays a pivotal role in gastric cancer pathogenesis and progression. Lab Invest. 2008;88:1358–1366. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agarwal R, Mori Y, Cheng Y, et al. Silencing of claudin-11 is associated with increased invasiveness of gastric cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olaru AV, Selaru FM, Mori Y, et al. Dynamic changes in the expression of MicroRNA-31 during inflammatory bowel disease-associated neoplastic transformation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan SH, Wu CW, Li AF, et al. miR-21 microRNA expression in human gastric carcinomas and its clinical association. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:907–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medina PP, Nolde M, Slack FJ. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 467:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi L, Chen J, Yang J, et al. MiR-21 protected human glioblastoma U87MG cells from chemotherapeutic drug temozolomide induced apoptosis by decreasing Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 activity. Brain Res. 1352:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziyan W, Shuhua Y, Xiufang W, et al. MicroRNA-21 is involved in osteosarcoma cell invasion and migration. Med Oncol. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9563-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selaru FM, Olaru AV, Kan T, et al. MicroRNA-21 is overexpressed in human cholangiocarcinoma and regulates programmed cell death 4 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3. Hepatology. 2009;49:1595–1601. doi: 10.1002/hep.22838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee TW, Coates LC, Birch NP. Neuroserpin regulates N-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion independently of its activity as an inhibitor of tissue plasminogen activator. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1243–1253. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kennedy SA, van Diepen AC, van den Hurk CM, et al. Expression of the serine protease inhibitor neuroserpin in cells of the human myeloid lineage. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:394–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. miR-21 is expressed at higher levels in gastric cancer (GC) vs. matched normal stomach (NS) specimens. The X-axis displays the type of specimen (GC vs. NS). The Y-axis shows fold difference in miR-21 expression between every GC specimen and the matched NS specimen.

Supplementary Figure 2. miR-21 is overexpressed in gastric cancer (GC) vs. normal stomach (NS) specimens based on RT-PCR data obtained for 79 specimens. miR-21 was found to be upregulated in GC compared to NS specimens. X-axis: specimens; Y-axis: RT-PCR values for miR-21. The average expression of miR-21 in NS was normalized to 1. The error bars signify Standard Error of the Mean.

Supplementary Figure 3. The level of Serpini1 mRNA increases with miR-21 inhibition. MKN28 gastric cancer cells were transfected with NSI and 21I and RT-PCR was performed to detect the level of Serpini1 mRNA. The increase in the level of Serpini1 mRNA is in line with the luciferase experiments and RT-PCR results on human gastric specimens.

Supplementary Figure 4. Luciferase activity is the same when cells are transfected with a construct that does not include miR-21 binding site. MKN28 cells were transfected with Seripini1 Rv then with NSI or 21I. The figure demonstrates that the luciferase intensity is approximately the same (p-value 0.9, unpaired Student’s t-test) for NSI and 21I.