Abstract

A molecular modeling strategy is proposed to describe the temperature (T) dependence of solubility parameter (δ) for the amorphous polymers which exhibit glass-rubber transition behavior. The commercial forcefield “COMPASS” is used to support the atomistic simulations of the polymer. The temperature dependence behavior of δ for the polymer is modeled by running molecular dynamics (MD) simulation at temperatures ranging from 250 up to 650 K. Comparing the MD predicted δ value at 298 K and the glass transition temperature (T g) of the polymer determined from δ–T curve with the experimental value confirm the accuracy of our method. The MD modeled relationship between δ and T agrees well with the previous theoretical works. We also observe the specific volume (v), cohesive energy (U coh), cohesive energy density (E CED) and δ shows a similar temperature dependence characteristics and a drastic change around the T g. Meanwhile, the applications of δ and its temperature dependence property are addressed and discussed.

Keywords: Glass transition temperature, Molecular simulation, Solubility parameter

Introduction

The solubility parameter, δ, concept provides a numerical estimate of the degree of interaction between materials, and can be a good indication of solubility, particularly for polymers [1–8]. As Bicerano emphasized in his book [8], the utilizations of polymers in many technological and industrial applications are critically dependent on their δ. The δ is often used in industry to predict the compatibility [1], permeation [1, 2], and swelling [2], bulk and solution properties [9–12] of polymers. In sensor applications δ can provide insights to predict the swelling changes of polymers in the presence of volatile chemical compounds [13, 14]. Furthermore, it is useful to optimize processing conditions, as well as select the suitable solvent or the optimum solvents combinations in coatings industry [2]. The δ for a pure compound is defined from Hildebrand-Scatchard solution theory as [3–7]

|

1 |

The δ is defined as the square root of the E CED. The E CED is the amount of energy needed to completely remove unit volume of molecules from their neighbors to infinite separation (an ideal gas), which is equal to the molar energy of vaporization (ΔH vap–RT) divided by molar volume (V) [4–6]. Equation 1 can then be converted to

|

2 |

where ΔH is the molar enthalpy of vaporization, R is the gas constant, with all physical quantities refering to the same temperature T. The division of the Hildebrand parameter into three component Hansen parameters (dispersion force, polar force, and hydrogen bonding force) can be expressed in terms of the individual solubility parameters δ d, δ p and δ h [6, 8]

|

3 |

where δ d, δ h, and δ p are respectively representing Hansen parameter contribution from dispersion, hydrogen bond, and polar interactions [6, 8].

The δ of polymers is a thermophysical property [12–14], and it shows high dependency to the temperature, T [2, 11–16]. In fact, the T g of a polymer is closely related to its δ [8, 12, 15, 16]. By considering the T effects on the fractional free volume (v f) and the enthalpy (H) change, Eqs. 4 and 5 have been proposed to describe the relationship between δ and T respectively above and below T g for the polymers exhibiting a glass-rubber transition.

For a temperature above Tg, T ≥ T g, the polymer is at rubbery state [15, 16]

|

4 |

where H

c(T

g) is a molar composite enthalpy at T

g consisting of a conformational and an intermolecular interaction component, α

l is the volume thermal expansion coefficient above T

g, M is the molar mass, v

l(T) is the specific volume above T

g, and ΔT equals the temperature difference with reference to  The v equals the reciprocal of its mass density (ρ); molar volume equals the molar mass divided by the mass density (ρ) (V = M/ρ). Thus, the molar volume can be expressed as V = vM. The molar mass of a polymer is a constant.

The v equals the reciprocal of its mass density (ρ); molar volume equals the molar mass divided by the mass density (ρ) (V = M/ρ). Thus, the molar volume can be expressed as V = vM. The molar mass of a polymer is a constant.

For a temperature below T g, T ≤ T g, a polymer at glassy state [15]

|

5 |

where  , with C

pl(T) and C

ps(T) being the specific heat capacities at a constant pressure (p) of the polymer in the liquid and glassy states at T respectively, and v

s(T) is the specific volume below T

g.

, with C

pl(T) and C

ps(T) being the specific heat capacities at a constant pressure (p) of the polymer in the liquid and glassy states at T respectively, and v

s(T) is the specific volume below T

g.

Although theoretical works [8, 12, 15, 16] have greatly contributed to the understanding of the relationship between δ and T, a number of fundamental questions remain uncovered, for example, more experimental data on δ at different T are required to support Eqs. 4 and 5. However, determination of δ at different T from experimental methods is time consuming and labor intensive. Moreover, Eqs. 4 and 5 are too complex to be applied practically. The δ can be considered to be linear proportional to T separately in a temperature above and below T g [15, 16]. Thus, Eqs. 4 and 5 can be are respectively simplified to two linear functions: For T ≤ T g, when the polymer is at glassy state (solid phase)

|

6 |

where δ g is the δ at T g and m s is the thermal coefficient of δ at glassy state (solid phase); For T ≥ T g, when the polymer is at rubbery state

|

7 |

where m l is the thermal coefficient of δ at rubbery state (liquid phase).

Equations 6 and 7 show simple mathematical relations between δ and T. Given the m s (or m l) and T g, δ at a given temperature can be calculated easily from the equations. The two equations and the material constants (m s, m l and T g,) is very important for the physical properties of the polymer. They can provide a fundamental understanding of temperature effects on the bulk and solution properties [1–8, 13, 14, 17] and also help in selecting or designing materials for specific applications. Moreover, they can be utilized in setting protocol for processes related to polymer–solvent interactions [1, 2, 15].

Literature [18–20] shows the possibility in calculating the δ of polymers via MD techniques. Additionally, simulations on bulk systems of moderate size (1000–5000 atoms) using recent systematically-derived “class II” forcefields such as “COMPASS” are capable of making predictions of δ with an accuracy that compares with experiment [21–25]. The forcefield describes approximately the potential energy hypersurface on which the atomic nuclei move. An accurate selection of forcefields is a key in enabling accurate predictions of the molecular interactions and material properties [17–25].

COMPASS is a powerful forcefield that supports atomistic simulations of condensed phase materials [23–25]. It has been parameterized and validated using condensed-phase properties in addition to various ab initio and empirical data for molecules in isolation [23, 24]. The forcefield enables accurate and simultaneous prediction of structural, conformational, vibrational, and thermophysical properties, that exist for organic molecules, inorganic small molecules, and polymers in isolation and in condensed phases, and under a wide range of conditions of temperature and pressure [23–25].

In this investigation, our objective is to model the temperature dependence characteristics of δ for emeraldine based polyaniline (EB–PANI) by using the COMPASS forcefield based MD techniques. The decrease of δ with increasing T for the polymer is plotted by running MD simulations at temperatures ranging from 250 up to 650 K and taking readings for δ at various temperatures. Due to the lack of published δ data at temperature other than 298 K, in order to verify the accuracy of our method, two kind of analysis has been are performed: (i) the δ value at 298 K for EB–PANI is predicted and compared with the literature reported data; (ii) the T g of the polymer is determined from the δ–T curve and compared with the experimental value. The temperature effects on the physical quantities (v, U coh and E CED) used in the definition of δ are also studied. The applications of the temperature dependence of δ on optimizing processing conditions will be addressed and discussed later in the discussion section.

Computational methodology

The use of atomistic methods to furnish a first principle calculation of E CED, is a desirable tool [18–25]. In atomistic simulations, the cohesive energy, U coh, is defined as the increase in energy per mole of a material if all intermolecular forces are eliminated [18, 19, 25]. The E CED corresponds to the cohesive energy per unit volume. It is a measure of the intermolecular forces within a system, and is estimated via the non-bonded van der Waals and electrostatic (includes hydrogen bond) interactions [18–20, 25, 26]. Equation 2 can be written in the form of:

|

8 |

where U vdw and U Q are respectively van der Waals and electrostatic energy [8, 14, 18–20, 25]. Hence, the δ can be formally expressed in terms of

|

9 |

where δ vdw and δ Q are respectively representing the contributions from van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions and

|

10 |

|

11 |

where E Q is the electrostatic energy density and E vdw is the van der Waals energy density. Counting hydrogen bonding energy to electrostatic energy results in

|

12 |

In the general case of a gas, liquid, or solid at a constant pressure, p, the volume thermal expansion coefficient, α, is given by

|

13 |

Since the thermal expansion gradients of α for above and below the T g are different, and it can be used to predict the T g of a polymer [25–28]. Applying Eqs. 8–13 to a polymer, the thermal properties of solubility parameter and its related cohesive properties can be investigated and established by MD simulation.

Molecular modeling details

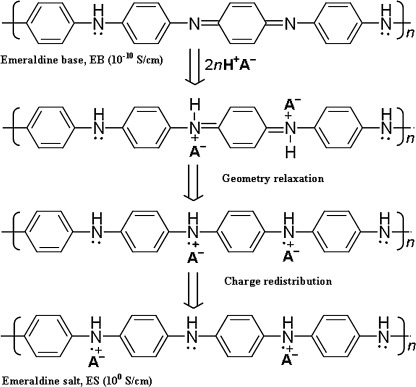

The polymer considered in this work is EB−PANI which consists of equal numbers of reduced (diamine) and oxidized (diimine) units: [(C6H4N)2(C6H4NH)2]n. It is regarded as one of the most useful conducting polymers due to its ease of synthesis, environmental stability and its semi-conductive characteristic upon protonic acid doping (Fig. 1) [25, 29–31]. Structurally, EB–PANI contains benzene rings and amine entity. The cohesive energy contributes from all types of interactions including the polar, the nonpolar (or dispersive), and the specific ones (or hydrogen bonding). The large amounts of benzene rings in the EB–PANI structure enhance the intermolecular interaction among the polymer chains [32–34]. These characteristics inherently make the physical properties of EB–PANI sensitive to temperature. EB−PANI is a good candidate for studying the thermal characteristics of δ and its related cohesive properties.

Fig. 1.

Non-oxidizing protonic acid (e.g., HCl, H2CO3) doping of EB–PANI: 2n is the number of protonic acid molecules, H+ is the proton, A− is an anion, e.g., chloride

The molecular simulations are performed by the Forcite Plus module of the commercial software Materials Studio® 5.0 using COMPASS forcefield. Simulation approaches include MM and MD with canonical ensemble (NVT) and isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT). All MD simulations are run with a 1.0 fs time step. In all MD simulations, temperature and pressure were controlled by the Berendsen’s method using a half-life for decay to the target temperature of 0.1 ps (decay constant) and 0.1 ps for the pressure scaling constant. The non-bonded electrostatic and van der Waals forces are controlled by “atom based” summation and a cutoff value of 15.5 Å is used.

Building the amorphous polymer system

The EB−PANI polymer molecule is constructed using the polymer builder based on its stereoisomerism (tacticity) and sequence isomerism (connectivity). The tacticity of the repeat units (Fig. 2a) in the constructed polymer is isotactic. The connectivity of the monomer units (Fig. 2a) is head-to-tail. After geometry optimization, polymer chains are assembled into a three-dimensional (3D) unit cell subject to periodic boundary conditions by an “Amorphous Cell” module. The “Amorphous Cell” module provides a comprehensive set of tools to construct 3D periodic structures of molecular liquids and polymeric systems. The module builds molecules in a cell in a Monte Carlo fashion, by minimizing close contacts between atoms, whilst ensuring a realistic distribution of torsion angles for any given forcefield [35]. Using this algorithm, an amorphous polymer structure can be built with realistic conformations, while minimizing the number of close contacts [25, 35].

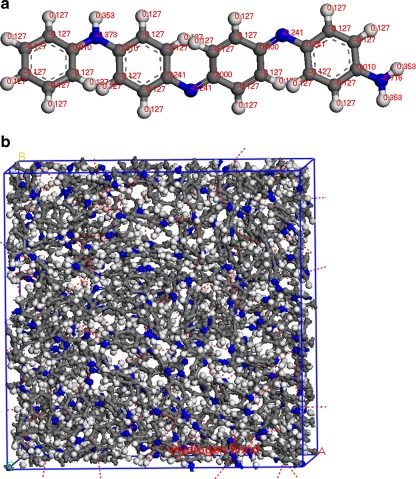

Fig. 2.

a Polymer monomer of EB–PANI with COMPASS forcefield assigned atomic charges. b Schematic illustration of a cubic unit cell for amorphous EB–PANI. Colors: carbon–gray, hydrogen–white, oxygen–red, nitrogen–blue, and hydrogen bond–red dotted line

In order to suppress surface effects while keeping the number of particles in the model to a reasonable size, 3D periodic boundary condition (PBC), in which the system is considered to be surrounded on all sides by replicas of itself (Fig. 2b), has been employed. The length of the cubic unit cell is about 34 Å with 3688 atoms (4 polymer chains) (Fig. 2b). Each polymer chain in the amorphous model has 20 monomers and the polymer density is 1.23 g/cm3 [25]. The atomic charges are forcefield assigned [23–25] and hydrogen bonding interactions have been monitored as illustrated in Fig. 2b.

Geometry optimization and equilibration of polymer system

To create a final structure with realistic density and low-potential-energy characteristics, polymer system is subjected to geometry optimization and an equilibration cycles. The Forcite geometry optimization is employed to refine the geometry of polymer structure until it satisfies a certain criteria with the settings listed in Table 1. Equilibration of polymer system is conducted by an equilibrating protocol which consists of 13 intermediate MD stages (NVT annealings and NPT equilibration) as described in Table 1 [25]. The purpose of an annealing strategy in equilibration is to find the different local minimum energy structures by using the higher temperature periods of each annealing cycle to overcome energy barriers.

Table 1.

Settings for geometry optimization and equilibration process of polymer system

| Geometry optimization | Equilibration process | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Forcefield: COMPASS | Step | Simulation conditions | Time (ps) |

| Charges: Forcefield assigned | 1 | NVT, 750 K | 50 |

| Summation method: Ewald for Electrostatic & van der Waals forces | 2 | A stepwise procedure of NVT of heating and cooling from 600K to 300 K by a step of 50 K | 50 ps/step |

| Algorithm: Smart | 3 | NVT, 298 K | 100 |

| Maximum iterations: Unlimited | 4 | NPT, 0.1 GPa, 298 K | 100 |

| Quality: Ultra-fine; | 5, 6 | Repeat step 2 and step 3 | as above |

| Energy (kcal mol−1): 2 × 10−5 | 7 | NPT, 3 GPa, 298 K | 100 |

| Force (kcal mol−1 Å−1): 0.001 | 8, 9 | Repeat step 2 and step 3 | as above |

| Stress (GPa): 0.001 | 10 | NPT, 0.5 GPa, 298 K | 100 |

| Displacement (Å): 1 × 10−5 | 11, 12 | Repeat step 2 and step 3 | as above |

| External pressure (GPa): 0.0 | 13 | NPT, 0.0001 GPa, 298 K | 1,500 |

Glass-rubber transition of polymer

Once the cell structures have been optimized and equilibrated, NPT–MD simulations over a range of temperature above and below the T g are employed to model the glass-rubber transition of polymer. Experimentally, the T g value of EB−PANI range over 460 K interval [(473 K) [33] or (523 K) [34]]. A series of NPT–MD simulations over a temperature range from 250 up to 650 K with an interval of 25 K (each of 500 ps) are carried out for the prediction of T g. The simulation is continued, with the input of the final state from the previous simulation trajectory. With the simulation trajectory from the NPT–MD simulations, the specific volume, v, and cohesive energy, U coh, at various temperatures is calculated. The δ and its related physical quantities (E CED, E vdw, E Q), can be calculated by running the Forcite cohesive energy density calculation on the series of structures generated. The three components, van der Waals energy (δ vdw), hydrogen bonding energy (δ h), and polar interaction (δ p) contribute to the total solubility parameter, δ, are reported with their associated standard deviation.

Results and discussion

Validation of model in predicting solubility parameter

In order to validate the accuracy, the δ of EB−PANI at 298 K have been predicted and compared with the empirical data. Shacklette and Han determined the total solubility parameters of EB−PANI at 298 K by using empirical measurement and group additive based on Eq. 3. The value of each component is δ d = 17.40 (J/cm3)1/2, δ h = 10.70 (J/cm3)1/2, and δ p = 8.10 (J/cm3)1/2, which is equivalent to a total solubility parameter of δ = 22.2 (J/cm3)1/2 [36–39]. The solubility parameters of EB−PANI at 298 K are estimated in the current MD study as follows: δ vdw = 17.94 (J/cm3)1/2, δ Q = 14.07 (J/cm3)1/2, and the total solubility parameter of δ = 22.80 (J/cm3)1/2, which are in reasonable agreement with the reported values as listed in Table 2) [36–39]. The agreement between simulation results and empirical data indicates that it is possible to predict the δ at various temperatures by MD.

Table 2.

Comparing the MD simulation predicted solubility parameters with experimental data (T = 298 K)

| Solubility parameter | Experimental data | MD predicted data |

|---|---|---|

| Dispersion (δ d) | 17.40 (J/cm3)1/2 | δ vdw = 17.94 (J/cm3)1/2 |

| Hydrogen bonding (δ h) | 10.70 (J/cm3)1/2 | δ Q = 14.07 (J/cm3)1/2 |

| Polar interaction (δ p) | 8.10 (J/cm3)1/2 | |

| Total solubility parameter (δ) | 22.20 (J/cm3)1/2 | 22.80 (J/cm3)1/2 |

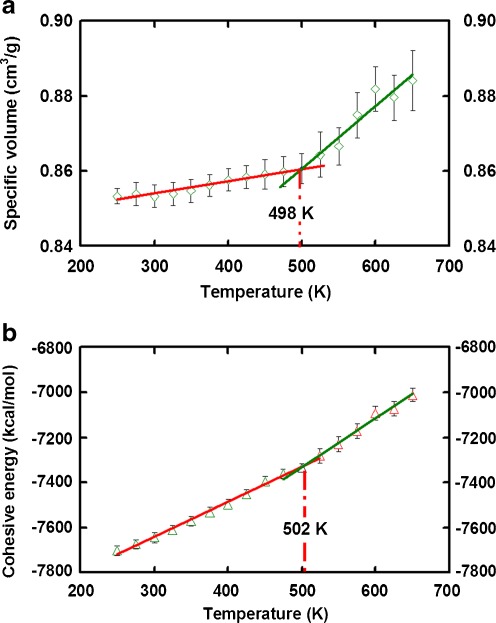

Temperature dependence of specific volume and cohesive energy

Figure 3a shows that the specific volume as a function of temperature ranging from 250 to 650 K. There is a discontinuity at temperature 498 K, which represents a different thermal expansion in the rubbery and glassy states. Two best-fit lines have been drawn to represent the thermal expansion below and above T g. The T g is estimated as the point of intersection (approximately 498 K) between two fit lines. Again, it agrees well with the experimental data which is 473 K [33] and 523 K [34]. In addition to specific volume, the cohesive energy of polymer shows a relatively sudden change at the T g. To verify this argument, we plot the variation of cohesive energy against the temperature. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, an insignificant discontinuity is observed in the vicinity of T g. The T g as determined from the cohesive energy plot is 502 K, which is within the reported range from 473 K [33] to 523 K [34] in the literature. As also indicates from the other groups [27, 28], it demonstrates that T g can be estimated from change of physical entities along temperature obtained from MD studies.

Fig. 3.

Plots of specific volume and cohesive energy against temperature. There is a break in both plots of (a) specific volume vs. temperature and (b) cohesive energy vs. temperature. Experimental glass transition temperature of T g = 473 K [33] or 523 K [34]

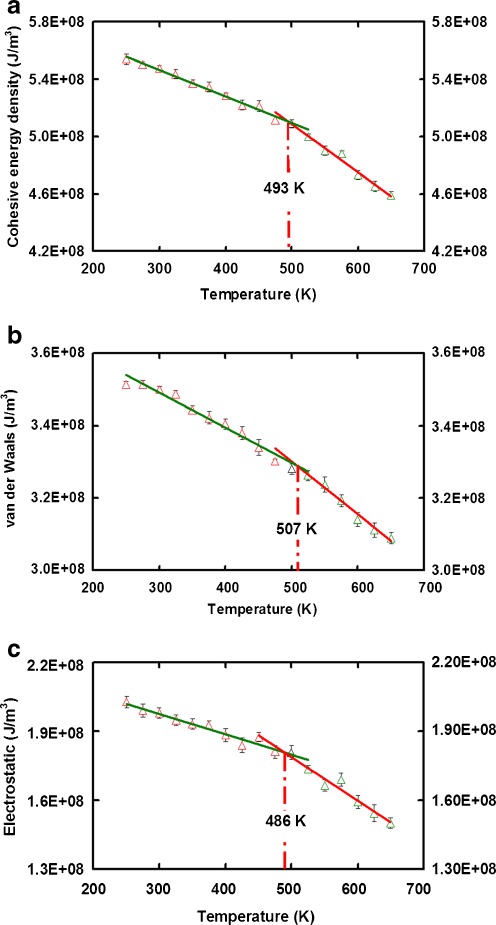

Temperature effects on the cohesive energy components related to solubility parameters

The thermal properties of total cohesive energy density, van der Waals energy, and electrostatic energy density used in defining δ, have been investigated. Figure 4a−c exhibit the various relationships between different physical entities and temperature (E CED vs. T, E vdw vs. T, and E Q vs. T). A noticeable break is detected from every plot. The corresponding temperature (493 K in Fig. 4a, 507 K in Fig. 4b, and 486 K in Fig. 4c) of these break are closed to the experimental T g data [33, 34]. These results indicate the cohesive energy density components versus temperature can also be used to determine T g. As formulated by Eq. 8, when an amorphous polymer undergoes a phase transition, the specific volume, cohesive energy, and cohesive energy density undergo a drastic change in the vicinity of the glass transition temperature, T g. The sudden jump at the glass transition temperature in these plots can be regarded as the evidence for Eqs. 4–7 from the previously theoretical works [8, 12, 15, 16].

Fig. 4.

Plots of cohesive energy density components related to solubility parameter against temperature. There is a discontinuous change in the vicinity of glass transition temperature, T g, in each plot of (a) cohesive energy density (b) van der Waals energy density (c) electrostatic energy density versus temperature. Experimental glass transition temperature of T g = 473 K [33] or 523 K [34]

Temperature dependence of solubility parameters

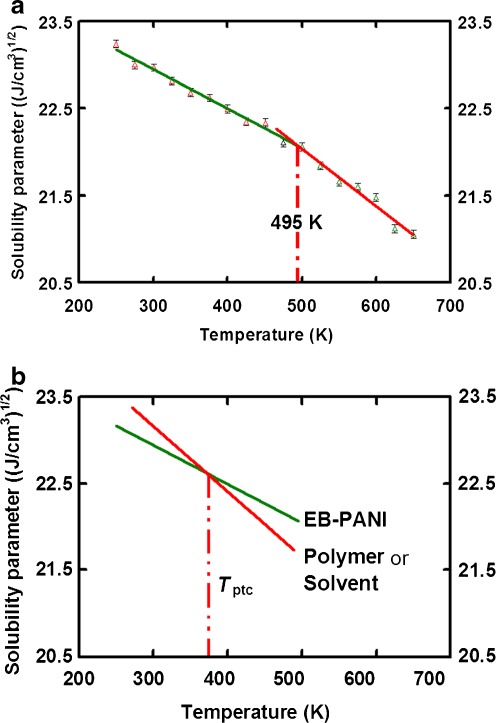

Figure 5a shows the variation of the δ of EB−PANI as a function of T ranging from 250 to 650 K. An abrupt change is noticeable at a temperature of 495 K which indicates the occurrence of glass transition. The curve can be split into two linear sections in below and above the breaking point (T g). In each linear section, the solubility parameter decreases with increasing temperature. The corresponding temperature (495 K) of the breaking point agrees well with the T g value ranges (486 K–507 K) predicted from Fig. 3a–b and Fig. 4a–c, and it is in reasonable agreement with experiment T g ranges from 473 K [33] to 523 K [34]. Since the T g is an important characteristic for amorphous polymer, we believe the accuracy in getting T g from the calculated δ can justify the validation in estimating the δ with MD method.

Fig. 5.

a Plots of solubility parameter against temperature. There is a break at T = 495 K in the plot, which indicates the occurrence of glass-rubber transition. Experimental glass transition temperature of T g = 473 K [33] or 523 K [34]. b An example to determine the suitable processing temperature condition (T ptc) by using the δ–T curve. The EB–PANI has the best miscibility (or best solubility) with the target polymer (or solvent) at T ptc

In applying Eqs. 6 and 7 to the current study, the thermal coefficient of solubility parameter at glassy state (m s) or liquid state (m l) and the solubility parameter at glass transition temperature (δ g) are calculated as:For T ≤ T g, the polymer at glassy state

|

14 |

where the thermal coefficient of solubility parameter at solid phase m s = −0.0045 ((J/cm3)1/2 T −1) and the solubility parameter at T g , δ g = 22.07((J/cm3)1/2.

For T ≥ T g, the polymer at glassy state

|

15 |

where the thermal coefficient of solubility parameter at liquid phase m l = −0.0066 ((J/cm3)1/2 T −1). Equation 14 and Eq. 15 are useful for EB−PANI in the technical and industrial applications. For instance, it can be used to select a second polymer in formulating a polymer composite; incorporating a second component into conducting polymer film is one of the most important methods to develop new sensors [13, 14]. In comparison with modification of molecular structure of conducting polymers, the advantage of this technique is that it can avoid complicated chemical syntheses. Using Eq. 14, we can determine the miscibility of two polymers and the suitable processing temperature condition (T ptc) in fabrication as illustrated in Fig. 5b. In another scenario, the equations can help in the optimization of processing conditions, as well as selecting appropriate solvents or predicting the suitable temperature (see Fig. 5b) for combinations in coatings industry [2].

Conclusions

The molecular modeling methodology, which is capable of investigating the temperature dependence characteristics of δ of amorphous polymer, has been formulated. The temperature effects on δ are studied by running MD simulations at various temperatures. From the δ–T curve, the glassy phase and the rubbery phase are clearly seen. The MD predicted results over the significant range (from 250 up to 650 K) of temperatures are conveniently fitted to the two linear equations (Eqs. 5 and 6) of the form. Comparisons with experimental data confirm the validity of our method. The δ, v, U coh, and E CED show a similar temperature dependence characteristics and a drastic change around the T g. Thus, the temperature dependence of δ and its related cohesive properties (v, U coh, and E CED) may be utilized in determining T g of a polymer which has the glass-rubber transition. Furthermore, the applications of the temperature dependence characteristics of δ have been addressed and discussed.

Acknowledgments

The study is supported by the Dutch Technology Foundation (STW) (Project No. 10058). We thank Prof. Dr. Cees J. M. van Rijn and Tin Doan from Wageningen University for their kind support and technical discussion.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Inzelt G. Conducting polymers a new era in electrochemistry. Berlin: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirsat MD, Bangar MA, Deshusses MA, Myung NV, Mulchandani A. Polyaniline nanowires-gold nanoparticles hybrid network based chemiresistive hydrogen sulfide sensor. Appl Phys Lett. 2009;94(083502):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scatchard G. Equilibria in non-electrolyte solutions in relation to the vapor pressures and densities of the components. Chem Rev. 1931;8:321–333. doi: 10.1021/cr60030a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hildebrand JH. Solubility. J Am Chem Soc. 1916;38:1452–1473. doi: 10.1021/ja02265a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildebrand JH. Solubility III. Relative values of internal pressures and their practical application. J Am Chem Soc. 1919;41:1067–1080. doi: 10.1021/ja02228a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton AFM. Solubility parameters. Chem Rev. 1975;75:731–753. doi: 10.1021/cr60298a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hildebrand JH, Prausnitz JM, Scott RL. Regular and related solutions: The solubility of gases, liquids, and solids. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bicerano J. Prediction of polymer properties. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardon JL. Relationship between cohesive energy densities of polymers and Zisman’s critical surface tensions. J Phys Chem. 1963;67:1935–1936. doi: 10.1021/j100803a515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girifalco LA, Good RJ. A theory for the estimation of surface and interfacial energies. I. derivation and application to interfacial tension. J Phys Chem. 1957;61:904–909. doi: 10.1021/j150553a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildebrand JH, Scott RL. The solubility of non-electrolytes. New York: Dover Publications; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes RA. The relationship between glass temperature, molar cohesion, and polymer structure. J Appl Polym Sci. 1961;5:318–321. doi: 10.1002/app.1961.070051511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanto N, Dougami N, Mukai T, Habara M, Kusano E, Kinbara A, Ogawa T, Oyabu T. A smart gas sensor using polymer-film-coated quartz resonator microbalance. Sens Actuators B. 2000;66:16–18. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4005(99)00450-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shevade AV, Ryan MA, Homer ML, Manfreda AM, Zhou H, Manatt KS. Molecular modeling of polymer composite–analyte interactions in electronic nose sensors. Sens Actuators B. 2003;93:84–91. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4005(03)00245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chee KK. Temperature dependence of solubility parameters of polymers. Malaysian J Chem. 2005;7:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka N. Prediction of solubility parameter from thermal transition behaviour in polymers. Polym. 1992;33:623–626. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(92)90741-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charles M, Hansen, Just L. Prediction of environmental stress cracking in plastics with Hansen solubility parameters. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2001;40:21–25. doi: 10.1021/ie9904955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick J, Marsac, Sheri L, Shamblin, Lynne S, Taylor L. Theoretical and practical approaches for prediction of drug–polymer miscibility and solubility. Pharm Res. 2006;23:2417–2426. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belmares M, Blanco LM, Goddard WA, III, Ross RB, Caldwell G, Chou SH, Pham J, Olofson PM, Thomas C. Hildebrand and Hansen solubility parameters from molecular dynamics with applications to electronic nose polymer sensors. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1814–1826. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tantishaiyakul V, Worakul N, Wongpoowarak W. Prediction of solubility parameters using partial least square regression. Int J Pharm. 2006;325:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun H, Rigby D. Polysiloxanes: ab initio forcefield and structural, conformational and thermophysical properties. Spectrochim Acta Part A. 1997;53:1301–1323. doi: 10.1016/S1386-1425(97)00013-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rigby D, Sun H, Eichinger BE. Computer simulations of poly(ethylene oxides): Forcefield, PVT diagram and cyclization behavior. Polym Int. 1998;44:311–330. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0126(199711)44:3<311::AID-PI880>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun H, Ren P, Fried JR. The COMPASS forcefield: parameterization and validation for polyphosphazenes. Comput Theor Polym Sci. 1998;8:229–246. doi: 10.1016/S1089-3156(98)00042-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun H. COMPASS: an ab initio forcefield optimized for condensed-phase application-overview with details on alkane and benzene compounds. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:7338–7364. doi: 10.1021/jp980939v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen XP, Yuan CA, Wong CKL, Zhang GQ. Validation of forcefields in predicting the physical and thermophysical properties of emeraldine base polyaniline. Mol Simulat. 2011;37:990–996. doi: 10.1080/08927022.2011.562503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barton AFM. Handbook of solubility parameters and other cohesion parameters. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu CF, Xu EJ. Atomistic molecular simulations of structure and dynamics of crosslinked epoxy resin. Polym. 2007;48:5802–5812. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2007.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fried JR, Li B. Atomistic simulation of the glass transition of di-substituted polysilanes. Comput Theor Polym Sci. 2001;11:273–281. doi: 10.1016/S1089-3156(00)00021-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang JC, MacDiarmid AG. Polyaniline: Protonic acid doping of the emeraldine form to the metallic regime. Synth Met. 1986;13:193–205. doi: 10.1016/0379-6779(86)90070-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacDiarmid AG. Nobel Lecture: “Synthetic metals”: a novel role for organic polymers. Rev Mod Phys. 2001;73:701–712. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.73.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDiarmid AG. Synthetic metals: a novel role for organic polymers. Synth Met. 2001;125:11–22. doi: 10.1016/S0379-6779(01)00508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowie JMG, Arrighi V. Polymers: chemistry and physics of modern materials. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pellegrino J, Radebaugh R. Gas sorption in polyaniline. 1. emeraldine base. Mattes Macromol. 1996;29:4985–4991. doi: 10.1021/ma951333x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei Y, Jang GW, Hsueh KF, Sherr EM, MacDiarmid AG, Epstein AJ. Thermal transitions and mechanical properties of films of chemically prepared polyaniline. Polym. 1992;33:314–322. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(92)90988-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theodorou DN, Suter UW. Shape of unperturbed linear polymers: polypropylene. Macromolecules. 1985;18:1206–1214. doi: 10.1021/ma00148a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shacklette L, Han C. Solubility and dispersion characteristics of polyaniline. Mat Res Soc: Symp Proc. 1994;328:157–166. doi: 10.1557/PROC-328-157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gregory RV, Jain R. Solubility and rheological characterization of polyaniline base in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone and N, N′-dimethylpropylene urea. Synth Met. 1995;74:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0379-6779(95)03372-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skotheim TA, Elsenbaumer RL, Reynolds JR. Handbook of conducting polymers. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Krevelen DW. Properties of polymers. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1990. [Google Scholar]