This study sought to understand why some women reject conventional breast cancer treatment and opt for unproven alternative therapy and to identify messages that might lead to greater acceptance of evidence-based treatment. Recommendations for physicians treating patients with early breast cancer are provided.

Keywords: Breast cancers, Patient compliance, Refusal of treatment

Abstract

Purpose.

Although breast cancer is a highly treatable disease, some women reject conventional treatment opting for unproven “alternative therapy” that may contribute to poor health outcomes. This study sought to understand why some women make this decision and to identify messages that might lead to greater acceptance of evidence-based treatment.

Patients and Methods.

This study explored treatment decision making through in-depth interviews with 60 breast cancer patients identified by their treating oncologists. Thirty refused some or all conventional treatment, opting for alternative therapies, whereas 30 accepted both conventional and alternative treatments. All completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Rotter Locus of Control scale.

Results.

Negative first experiences with “uncaring, insensitive, and unnecessarily harsh” oncologists, fear of side effects, and belief in the efficacy of alternative therapies were key factors in the decision to reject potentially life-prolonging conventional therapy. Refusers differed from controls in their perceptions of the value of conventional treatment, believing that chemotherapy and radiotherapy were riskier (p < .0073) and less beneficial (p < .0001) than did controls. Controls perceived alternative medicine alone as riskier than did refusers because its value for treating cancer is unproven (p < .0001). Refusers believed they could heal themselves naturally from cancer with simple holistic methods like raw fruits, vegetables, and supplements.

Conclusion.

According to interviewees, a compassionate approach to cancer care plus physicians who acknowledge their fears, communicate hope, educate them about their options, and allow them time to come to terms with their diagnosis before starting treatment might have led them to better treatment choices.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a common disease, with 200,000 new cases and 40,000 deaths each year in the U.S. [1]. Early breast cancer is, however, a highly treatable condition, with current conventional treatment modalities such as surgery (often combined with radiation) and adjuvant drug treatment (chemotherapy, hormones, and trastuzumab, depending on the biologic characteristics of the tumor). A patient diagnosed today with early breast cancer has an excellent prognosis for cure, unless a negative prognostic feature such as extensive axillary lymph node involvement is present.

Many women with breast cancer choose a combination of conventional cancer treatment and alternative medicine [2]. Some seek a balance between conventional treatments to cure their disease and alternative therapies that they believe can strengthen the immune system and mitigate the side effects of treatment. However, there are patients with breast cancer who refuse some or all recommended conventional treatments, opting for alternative regimens alone. There are few data on the extent of this problem, but oncologists see these patients in their practices and the issue is discussed anecdotally in the literature [3].

Alternative therapies among breast cancer patients is one of the fastest-growing treatment modalities in the U.S. [4]. There is evidence, however, that patients with early breast cancer who refuse conventional breast cancer treatment and rely instead on alternative therapies alone experience a higher rate of recurrence and death [5, 6]. Although there is much research on why women with breast cancer use alternative therapies, there are few studies on why many do so to the exclusion of conventional treatment. Considering that breast cancer is now a highly treatable disease and the mounting evidence that patients who initially forgo conventional protocols have poor outcomes [6, 7], it is important to understand the motivations that underlie this decision and what can be done to encourage these women to accept evidence-based treatment.

According to the breast cancer literature, reasons for declining conventional treatment in favor of alternative therapies include: need for control [8–11], fear of adverse effects [7, 10], dissatisfaction and poor communication with physicians [4, 7, 8, 10, 11], and perceived outcomes and toxicity of treatment [7, 8, 11]. This suggests that there are potentially modifiable barriers to choosing conventional therapy that might be addressed through better communication and educational initiatives aimed at both patients and physicians.

The objectives of this study were to: (a) understand the beliefs and perceptions that underlie the decision to refuse conventional treatment in favor of alternative therapies, (b) identify messages and approaches that might increase the likelihood of women accepting conventional therapy (particularly in the adjuvant setting), and (c) provide treating physicians with recommendations for better management of these patients.

Patients and Methods

Patient Population

Sixty in-depth telephone interviews were conducted with breast cancer patients from the Midwestern Regional Medical Center (MRMC) in Zion, IL, a cancer treatment facility operated by Cancer Treatment Centers of America (CTCA). The recruitment and interviews spanned 8 months from February–October 2009.

With its reputation as a patient-empowered cancer center offering state-of-the-art, integrative, multidisciplinary treatment, MRMC attracts a large number of breast cancer patients who previously refused conventional treatment elsewhere. All participants reported seeking consultation and/or treatment at a community hospital or university medical center before coming to MRMC. Women recruited for the study were breast cancer patients aged <70 years with at least a high school education.

Thirty interviews were conducted with women who, when first diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, refused some or all recommended conventional treatments in favor of alternative approaches (hereafter, refusers). Thirty additional interviews were conducted with a comparison group who accepted conventional treatment and alternative therapies at the outset (hereafter, acceptors). Acceptors were chosen to reflect the racial mix and education level of refusers. The women were at variable stages in the course of their disease when interviewed. The study was approved by the institutional review board at CTCA-MRMC.

Sampling and Preinterview Process

Breast cancer patients who met the study criteria were identified by their treating oncologists. At their scheduled medical appointments, the study coordinator provided patients with verbal and written information about the study and requested their participation. Those who chose to participate signed consent forms at that time. They also completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Rotter Locus of Control scale to assess differences in trait anxiety and locus of control between the two groups. The BAI is a 21-item scale that measures the severity of self-reported anxiety. The Rotter Locus of Control scale is a 23-item questionnaire. “Externals” tend to perceive what happens to them as the result of luck, fate, or powerful others whereas “internals” believe what happens to them is generally under their own control.

Interview Process

Interviews were conducted using an open-ended topic guide that assured that all patients were asked the same questions but also allowed the interviewer to introduce additional questions as appropriate to the dynamics of each interview. This methodology was chosen because it allowed for in-depth exploration of topics. The discussion focused on treatment decision making after diagnosis, perceptions of treatment options, reasons some declined conventional treatment, and what might have changed their minds.

Eight quantitative questions asked patients to rate, on a 10-point Likert scale, their perceptions of the risks and benefits of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and alternative therapies. The interviews lasted approximately 1 hour and were audiorecorded.

Data Analyses

The interviewer reviewed audiotapes, making detailed notes including verbatim quotes in preparation for a systematic qualitative analysis. All quotes were assigned to a content category from one of the constructs in the topic guide, for example, “perceptions of chemotherapy.” The interviewer reviewed the quotes in each category, noting which point(s) of view prevailed and which were less common in order to identify the strongest themes with particular attention to “barriers to conventional medicine” and “overcoming those barriers.”

χ2 statistics were used to analyze categorical variables. Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks was used to test equality of population medians among groups.

An effect was considered statistically significant if the p-value was ≤.05. All statistical tests were two sided. All data were analyzed using JMP® 8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Pre-CTCA Patient Experience

Refusers used alternative therapies such as raw fruits and vegetables, juicing, supplements, and prayer. Some chose more extreme therapies like colon cleanses, proprietary herbs, and salves purported to dissolve tumors, insulin-potentiated chemotherapy, Laetrile, and treatment involving lasers, oxygen, and ozone. Some pursued treatments at Mexican clinics under practitioners with questionable credentials. All who reported travelling for such alternative treatments believed that these therapies would cure them. They came to MRMC after obvious disease progression. Almost all who initially rejected conventional treatment ultimately accepted it at MRMC, but did so generally when the disease was no longer curable.

Treatment at CTCA

All patients treated at CTCA received conventional breast cancer treatment appropriate for their stage and biological type of disease, consistent with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines [12].

In addition, all patients were offered alternative therapies designed to reduce treatment side effects and to support their general health while receiving conventional treatment, consistent with the CTCA integrative breast cancer treatment model. These measures included nutritional counseling and support, evidence-based naturopathic medicine, vitamin and supplement therapy, acupuncture, massage, spiritual support, and mind–body medicine.

Attitudes and Beliefs of Refusers

Looking back to the time of initial diagnosis, most refusers reported that they were neither opposed to conventional treatment nor deeply rooted in alternative medicine. In fact, all started out in the conventional medical arena. At that time, refusers reported knowing little about breast cancer treatment. Most recalled a fear of dying and of treatment side effects and said that they needed time to absorb the shock of their diagnosis and educate themselves about options.

Their reasons for rejecting conventional therapy included: negative experiences with physicians soon after diagnosis, belief in holistic therapy as a viable alternative, perceptions that chemotherapy and radiotherapy were high risk and low benefit, and misinformation.

Negative Experiences with Physicians

Negative experiences with physicians soon after their diagnosis drove many refusers away from conventional medicine into the hands of holistic practitioners that they perceived as more compassionate.

Looking back, refusers reported dissatisfaction with their initial oncologists, describing them as “intimidating,” “cold,” “uncaring,” “unnecessarily harsh,” “thinking they were God,” and “not even knowing [their] names.” Some reported difficulty getting lab results and said their physicians became adversarial when questioned about treatment recommendations. Refusers also said that their physicians gave them little reason for hope. Some refusers perceived their doctors as dismissive of their wishes to incorporate alternative medicine into their regimens. Some said their doctors did not understand the depth of their fear and tried to pressure them to make quick treatment decisions while they were still trying to adjust to their diagnosis. Refusers became cynical about their physicians' motives for rushing them into chemotherapy, suspecting it was more about institutional pressure and big money than about the patient's well-being. Some became further alienated when their physicians used fear tactics to convince them to accept conventional treatment, for example, “You'll never live to see your grandchildren born.”

Almost all described the way they were treated as impersonal, and few believed their doctors were working in their best interests. Refusers said they left conventional medicine in search of more caring practitioners who offered hope, encouragement, and less toxic treatment.

Belief in Alternative Therapy as a Viable Option

From their research (the Internet, other patients, networking), refusers concluded that they could cure themselves naturally from cancer. All viewed alternative therapy as a viable and safer option than conventional treatments. None were aware of studies suggesting that alternative therapies used as primary cancer treatment are associated with poor outcomes. In fact, most refusers believed that there were no outcome studies of alternative therapies because “there's no big money in it.” Some assumed that if there were studies, those would demonstrate alternative therapies to be as effective as conventional treatments with less toxicity.

Perceptions of the Risks and Benefits of Conventional Treatment

Although open to some aspects of conventional treatment, for example, surgery, many drew the line at chemotherapy and radiotherapy, which they perceived as high risk and low benefit. Refusers knew of chemotherapy's negative impacts but felt they were inadequately informed of its benefits or focused on risks over benefits when making initial treatment decisions. Many characterized chemotherapy as a “poison” and feared that conventional cancer treatments would weaken their body's ability to fight cancer, but that alternative treatments intended to boost the immune response would strengthen it.

The origin of many of these patients' negative perceptions of cancer treatment was previous experience with family members who died from cancer after suffering through treatment. Some of the patients said they were less afraid of dying than of suffering the side effects of treatment. Their own Internet research, finding celebrity testimonials of alternative cancer cures, and claims of holistic practitioners bolstered those beliefs.

Misinformation

Refusers had little knowledge of breast cancer treatment protocols proven to be effective for particular tumor types and did not understand the importance of compliance: even relatively minor deviations from guidelines can result in poorer outcomes. Therefore, when physicians presented them with treatment plans based on guidelines, refusers criticized their perceived one-size-fits-all approach.

Some refusers were also not well informed about the need for follow-up treatment after surgery, believing that if they had clean margins, they did not need chemotherapy or radiation because a healthy diet and lifestyle would keep the cancer from recurring.

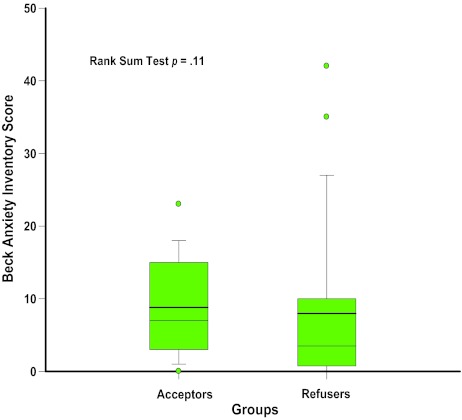

Differences Between Refusers and Acceptors

Refusers and acceptors were well matched demographically and in terms of initial breast cancer stage (Tables 1 and 2). Additionally, they showed no significant differences in locus of control or trait anxiety (Figs. 1 and 2). Both groups reported significant fear after their diagnosis and recalled negative experiences or poor communication with their first physicians. Despite their similarities, the two groups made very different treatment decisions. By definition, women in the acceptor group chose mainstream cancer treatment supported by alternative therapies whereas refusers declined conventional cancer treatment and chose alternative medicine as their primary cancer treatment.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of acceptors versus refusers

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of acceptors versus refusers

Figure 1.

Rotter Locus of Control results: 30 acceptors compared with 26 refusers.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Beck Anxiety Inventory scores by refusers (n = 30) and acceptors (n = 25).

One of the most notable differences between the groups was their perception of the value of treatment options (Tables 3 and 4). These tables are based on a sample of 29 acceptors and 27 refusers because one acceptor and three refusers chose not to answer the risk–benefit questions. Refusers perceived chemotherapy and radiotherapy as riskier (p < .001) and less beneficial (p < .0001) than did acceptors. Acceptors also perceived chemotherapy as risky, but considered it more beneficial than refusers did and a “necessary evil” for long-term survival. Acceptors perceived alternative medicine alone as holding greater risk with less benefit than did refusers (p < .0001), because its value for treating cancer was unproven. Whereas refusers believed they could heal themselves from cancer using only alternative therapies, this was, by definition, never an option for the acceptors, who were unwilling to take a chance on therapies not supported by data.

Table 3.

Perceived risks of therapy

On a scale of 0–10, patients were asked to evaluate the risks (0, no risk; 10, maximum risk) of therapy. The table contains mean values of patient scores.

Table 4.

Perceived benefits of therapy

On a scale of 0–10, patients were asked to evaluate the benefits (0, no benefit; 10, maximum benefit) of therapy. The table contains mean values of patient scores.

From the interviews, acceptors appeared to have more adaptive coping skills than refusers, as revealed in their descriptions of their reactions to fear at diagnosis and its impact on decision making. Although the women in both groups said that they experienced intense fear when diagnosed, refusers remained overwhelmed whereas acceptors got beyond their fear and proceeded to making treatment decisions. Both groups were very apprehensive about receiving chemotherapy, but whereas refusers focused on the risk of irreversible damage, acceptors focused on the short-term nature of the treatment, its long-term benefit, and alternative therapies to mitigate side effects and keep their bodies strong. Whereas refusers believed that they had time to cure themselves naturally before trying conventional treatments, acceptors believed that time was of the essence in getting treatment before the cancer spread.

Discussion

It is particularly frustrating for health care providers when patients with a potentially curable disease refuse conventional treatment of demonstrated efficacy in favor of unproven methods of “treatment.” This study was designed to provide treating physicians with insights into why some women make this decision and to identify messages that would have led them to more appropriate treatment choices.

The interviews revealed that patients' treatment decisions have both rational and emotional components and that it is not enough for oncologists to merely make good treatment recommendations—the way those recommendations are communicated can make a large difference in patient acceptance.

When the refusers were first diagnosed, they experienced significant fear, which was intensified after their first interactions with oncologists. Fear plus misinformation led many to seek holistic practitioners who gave them hope, promised a cure, and offered less-toxic treatment alternatives. Unfortunately, those practitioners did not have the expertise or credentials to treat cancer, and in all cases the women's disease progressed.

It is likely that many of the oncologists who used fear tactics, such as “You won't live to see…” did so in an attempt to motivate their patients to accept conventional treatment. However, refusers reported that such statements made them defensive and suspicious that the treatment was being “pushed” purely for profit. Ironically, the impact of such statements was to drive patients away from that physician and institution, and sometimes away from conventional medicine altogether.

Refusers said that, looking back, a better first experience with their physicians might have made a difference in the treatment path they ultimately chose. They said that they would have been more likely to accept conventional treatment earlier had they felt that they had caring physicians who acknowledged their fears, communicated hope, educated them about treatment possibilities, and allowed them time to adjust to their diagnosis and assimilate information before starting treatment.

Six Recommendations for Physicians Treating Patients with Early Breast Cancer

During the interviews, refusers were asked what could have been done to have increased their likelihood of accepting conventional treatment. The following recommendations for physicians are based on their responses. These principles would be beneficial, in general, for all breast cancer patients but could mean the difference between life and death for this particular subset of women.

Be compassionate and nonjudgmental. How treatment recommendations are communicated is as important as the recommendations themselves. Take time to answer patients' questions.

Give words of hope appropriate to each situation. Do not give false hope, but do not take all hope away. Acknowledge the deep fear that patients experience when diagnosed with cancer.

Underscore the patient's decision-making power. Explain your treatment recommendations but emphasize that the final decision rests with her. Describe the treatment program realistically but emphasize measures that minimize toxicity and discomfort.

Give patients time to decide. Don't unduly pressure them or rush them into starting treatment; avoid fear tactics to convince them to accept conventional treatment. Patients need time to come to terms with their diagnosis and assimilate a large amount of information before committing to treatment. Take extra time with patients who need it.

Be supportive but realistic. Acknowledge the patient's wish to use alternative therapies but explain that breast cancer is too powerful to treat with alternative methods alone. Share the results of studies supporting conventional treatment protocols as well as those showing that alternative therapies used as primary treatment lead to recurrences and death.

Explain your position. Clarify that you are not recommending a one-size-fits-all approach to cancer treatment. Breast cancer treatment guidelines are based on scientific studies that have demonstrated success with particular tumor types. Emphasize the importance of complying with those protocols, because even minor deviations can lead to poorer outcomes.

Some limitations of this study require careful acknowledgment. Qualitative research techniques can provide useful, detailed insights into a target audience's perceptions and beliefs. However, by definition, data gathered qualitatively are not as objective or clear-cut as quantitative data and may not necessarily be generalizable to a larger audience. Rather, these findings are intended to give oncologists a sense of how a particular subset of women thinks about treatment and how physicians can help them make better decisions. In these interviews, patients looked back to their experiences after diagnosis. Such retrospective techniques may not accurately reflect patients' thinking in the midst of these experiences. In spite of these limitations, the interviews yielded strong, consistent themes.

Another potential limitation of this study is that all interviewees were recruited from one site, putting in question the generalizability of the findings. However, given that all study participants came from other university medical centers or community hospitals in 23 states, the sample is diverse.

The subset of breast cancer patients who are inclined to forgo conventional treatment in favor of a holistic approach presents a perplexing problem that is not frequently discussed in the literature. The women who declined conventional therapy reported that differences in communication style and the information conveyed might have changed their decisions. Our research suggests means to improve education and communication, which may translate into more evidence-based decision making and better outcomes.

In conclusion, there is a steep learning curve for both physicians and patients who find themselves in this scenario. Patients need time to come to terms with having cancer, to reduce their fear level, and to digest a great deal of information. Physicians need to understand these women's mindsets, their barriers to conventional treatment, and their need for assurances that their physicians have their best interests at heart.

See the accompanying commentary on pages 590–591 of this issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeffrey Peppercorn of Duke University Medical School for his input and guidance with this manuscript.

This study was funded by Cancer Treatment Centers of America at Midwestern Regional Medical Center, Zion, IL.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Dennis L. Citrin, Diane L. Bloom, James F. Grutsch, Sara J. Mortensen, Christopher G. Lis

Provision of study material or patients: Dennis L. Citrin, Diane L. Bloom, James F. Grutsch, Sara J. Mortensen, Christopher G. Lis

Collection and/or assembly of data: Dennis L. Citrin, Diane L. Bloom, James F. Grutsch, Sara J. Mortensen, Christopher G. Lis

Data analysis and interpretation: Dennis L. Citrin, Diane L. Bloom, James F. Grutsch, Sara J. Mortensen, Christopher G. Lis

Manuscript writing: Dennis L. Citrin, Diane L. Bloom, James F. Grutsch, Sara J. Mortensen, Christopher G. Lis

Final approval of manuscript: Dennis L. Citrin, Diane L. Bloom, James F. Grutsch, Sara J. Mortensen, Christopher G. Lis

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris KT, Johnson N, Homer L, et al. A comparison of complementary therapy use between breast cancer patients and patients with other primary tumor sites. Am J Surg. 2000;179:407–411. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groopman J. New York: Penguin Books; 1997. Measure of Our Days: A Spiritual Exploration of Illness; pp. 114–138. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirois FM, Gick ML. An investigation of the health beliefs and motivations of complementary medicine clients. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boon H, Brown JB, Gavin A, et al. Breast cancer survivors' perceptions of complementary/alternative medicine (CAM): Making the decision to use or not to use. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:639–653. doi: 10.1177/104973299129122135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang EY, Glissmeyer M, Tonnes S, et al. Outcomes of breast cancer in patients who use alternative therapies as primary treatment. Am J Surg. 2006;192:471–473. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shumay DM, Maskarinec G, Kakai H, et al. Why some cancer patients choose complementary and alternative medicine instead of conventional treatment. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montbriand MJ. Abandoning biomedicine for alternate therapies: Oncology patients' stories. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21:36–45. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199802000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truant T, Bottorff JL. Decision making related to complementary therapies: A process of regaining control. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verhoef MJ, White MA. Factors in making the decision to forgo conventional cancer treatment. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:201–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.104002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verhoef MJ, Rose MS, White M, et al. Declining conventional cancer treatment and using complementary and alternative medicine: A problem or a challenge? Curr Oncol. 2008;15(suppl 2):s101–s106. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i0.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson RW, Brown E, Burstein HJ, et al. NCCN Task Force report: adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4(suppl 1):S1–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]