Ninety-one elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma were given tailored treatment based on the results of a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Treatment was feasible with encouraging outcomes.

Keywords: Elderly patients, DLBCL, CGA, R-CHOP

Learning Objectives:

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Demonstrate the proper use of a simplified comprehensive geriatric analysis, including activities of daily living (ADL), Mini-Mental State Evaluation (MMSE), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatrics (CIRS-G), and geriatric syndromes (multidimensional geriatric assessment [MGA]).

Maintaining a tailored anthracycline-based therapy, describe alternative treatment in elderly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients unfit for the standard chemotherapy.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

Background.

Elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) are a heterogeneous population; clinical trials have evaluated a minority of these patients.

Patients and Methods.

Ninety-one elderly patients with DLBCL received tailored treatment based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). Three groups were identified: I, fit patients; II, patients with comorbidities; III, frail patients. Group I received 21-day cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP-21), group II received R-CHOP-21 with liposomal doxorubicin, and group III received 21-day cycles of reduced-dose CHOP. Fifty-four patients (59%) were allocated to group I, 22 (25%) were allocated to group II, and 15 (16%) were allocated to group III.

Results.

The complete response (CR) rates were 81.5% in group I, 64% in group II, and 60% in group III. With a median follow-up of 57 months, 42 patients are alive, with 41 in continuous CR: 31 patients (57%) in group I, seven patients (32%) in group II, and four patients (20%) in group III. The 5-year overall survival, event-free survival, and disease-free survival rates in all patients were 46%, 31%, and 41%, respectively. Multivariate analysis selected group I assignment as the main significant prognostic factor for outcome.

Conclusions.

This approach in an unselected population of elderly DLBCL patients shows that treatment tailored according to a CGA allows the evaluation of elderly patients who are currently excluded from clinical trials.

Introduction

In western countries, about half of the patients with newly diagnosed aggressive CD20+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) are aged ≥65 years [1], with older patients having a poorer prognosis according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI) [2]. Elderly patients with DLBCL comprise a heterogeneous population, and because of a greater prevalence of comorbidities and poor performance status (PS) scores, they are often excluded from clinical trials and treatment [1, 3]. The definition of elderly has been approached in several trials, including those with high-dose therapy, wherein the age limits were in the range of 55–70 years [4–6]. Today, age is no longer a contraindication to autologous stem cell transplantation in patients aged >70 years with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) [7, 8].

Although cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) therapy appears to be more toxic in patients aged >70 years [9, 10], age cutoff alone is not an adequate parameter to discriminate patients at higher risk for severe toxicity after conventional treatment, and indeed, since the incorporation of rituximab into the CHOP schedule (R-CHOP), which is now the standard of care for DLBCL patients [11], outcomes in elderly patients have improved [12]. This schedule was evaluated in the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) trial [13] with a conventional interval of 3 weeks in so-called fit elderly patients and in the RICOVER-60 trial [14], which evaluated the R-CHOP schedule in the same setting, both the conventional regimen and a shortened schedule. However, in the GELA trial, patients were eligible for treatment based on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS evaluation. Furthermore, some exclusion criteria did not appear to be unequivocally defined, such as serious active concomitant disease not otherwise specified and patient's general condition unsuitable for the administration of eight courses of CHOP as judged by the investigator. Finally, the study also excluded patients with cardiac contra-indications to doxorubicin, or neurologic contraindications to vincristine. Similarly, in the RICOVER-60 trial, impairment of cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal function was an exclusion criterion that was not well defined, as was a poor PS.

Currently, individual functional reserve and life expectancy can be reliably evaluated by means of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) [15]. However, it is not clear whether or not a CGA may help estimate the risks and benefits of treatment in patients with hematological malignancies. CGA can, however, help recognize patients with different life expectancies—patients who are functionally independent and without serious comorbidities, who are expected to have the best outcome, frail patients, and patients in a grey zone, who are not completely independent or may have relevant comorbidities [16, 17].

Nonetheless, to date, it appears that no studies have ever evaluated the feasibility of a preliminary CGA for tailored treatment, nor has CGA been prospectively tested in a large population in the setting of aggressive lymphomas. Moreover, data on use of anthracycline-containing regimens in DLBCL patients unfit for conventional therapy are limited. Finally, there are still no prospective trials aimed at evaluating this approach in terms of outcome in an unselected population of elderly patients with DLBCL.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

This was a prospective, multicenter, observational study. The primary endpoint was the outcome of an unselected population of elderly patients with DLBCL receiving a tailored treatment based on a simplified multidimensional geriatric assessment (MGA). Secondary endpoints were: (a) the feasibility of using the MGA and distributing patients into different risk groups according to their MGA score; (b) evaluation of the toxicity, response rate, and outcome according to MGA score and tailored treatment.

The study was approved in September 2002 by our institutional review board and was performed in accordance with the principles set by the Helsinki Declaration. All patients gave written informed consent. Data collection was centralized in our center, which was the coordinating center.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and the Geriatric Assessment

The study consecutively enrolled 91 elderly patients aged ≥65 years with CD20+ DLBCL, according to the Revised European–American Lymphoma World Health Organization (WHO) classification [18, 19], from October 2002 to November 2006 in nine centers across the region of Marche, Italy. After pathological confirmation, all patients were given the MGA, which assessed the risk for treatment and allocated patients to specific groups for tailored treatment.

Exclusion criteria were DLBCL localized in the central nervous system (CNS), HIV infection, previous treatment with chemotherapy or rituximab, a second malignancy (excluding in situ skin or prostate cancer), the inability to give informed consent, the lack of transportation, and the lack of a caregiver in cases of frail patients.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients. The median age was 74 years. Twenty-seven patients (30%) had a (non–age-adjusted) IPI score ≥3 [2]. Twenty-five patients (27%) had systemic symptoms.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 91 patients enrolled

To make statistical comparisons among the three groups consistent, the risk categories according (non–age-adjusted) IPI score were dichotomized into low–intermediate risk (score ≤2) and intermediate–high risk (score ≥3).

Abbreviations: IPI, International Prognostic Index; ns, not significant.

At baseline, patients underwent clinical tests evaluating blood chemistry and lactate dehydrogenase, a bone marrow biopsy, a total body computed tomography (CT) scan, electrocardiography, left ventricular ejection fraction evaluation, forced expiratory volume assessment, and evaluation of carbon monoxide diffusion capacity. Patients at high risk for CNS involvement also underwent a lumbar puncture.

The MGA was performed using a simplified CGA proposed by Balducci and Extermann [16] based on age, functional status, comorbidities, and geriatric syndromes. Assessment of socioeconomic conditions and emotional and cognitive conditions that could interfere with comprehension of treatment plans was performed with standardized questionnaires (supplemental online data). Cognitive status was assessed using the Folstein Mini-Mental State Evaluation (MMSE) [20].

Functional status was evaluated according to an activities of daily living (ADL) scale, including the following six abilities: feeding, continence, grooming, dressing, functional transferring, and ambulation [21].

Comorbidities were evaluated using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatrics (CIRS-G) [22], and the severity of concomitant conditions was evaluated according to the following scale: 0, absent; 1, light, not interfering with normal activities, therapy optional; 2, moderate, interfering with normal activities, needing treatment, with a good prognosis; 3, serious, disabling, requiring urgent treatment, prognosis reserved; 4, very serious, potentially lethal, emergency therapy needed.

Geriatric syndromes were as follows: dementia (previously established clinical diagnosis or defined by a MMSE score <24), delirium appearing during simple infections or during treatment with drugs that would normally not cause delirium, depression refractory to treatment, falls (three or more in 1 month), complete and irreversible fecal or urinary incontinence, osteoporosis with spontaneous fractures, neglect or abuse (e.g., a patient wearing dirty clothes with spots of organic liquids or signs of abuse at two or more consecutive visits) [23, 24].

The criteria for identifying a frail patient were established as: age ≥85 years, dependence for one or more ADLs, the presence of one or more geriatric syndromes. The occurrence of one or more severe comorbidities (CIRS-G score ≥3) was sufficient to define a frail patient, whereas the presence of two or fewer moderate concomitant comorbidities (CIRS-G score, 0–2) was not.

The MGA was performed at each participating center by a senior hematologist in cooperation with a trained nurse using standard forms that had been reviewed centrally. Based on the MGA score, 91 patients were allocated into three different risk groups, each receiving a treatment tailored to their age group. Baseline characteristics (Table 1) were used to make group assignments (Table 2). No differences were noted regarding distribution according to sex, IPI score, and stage, whereas there were differences in the age distribution. Feasibility of the MGA was measured as the ability to complete the MGA by each eligible patient, that is, the number of patients enrolled after MGA evaluation divided by the number of patients registered before MGA evaluation (according to the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Table 2.

Allocation of patients into three risk groups according to MGA score

aGeriatric syndromes: 1, osteoporosis with fracture; 2, dementia and depression.

bComorbidities scored ≥2 according to the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatrics.

cR-CHOP-21: cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2), doxorubicin (50 mg/m2), and vincristine (1.5 mg/m2) on day 1; prednisone (60 mg/m2) on days 1–5; rituximab (375 mg/m2) was administered on day 1 for each of the six courses.

dR-CDOP-21: cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2), liposomal doxorubicin (30 mg/m2), and vincristine (1.5 mg/m2) on day 1; prednisone (60 mg/m2) on days 1–5; rituximab (375 mg/m2) was administered on day 1 for each of the six courses.

eMini-CHOP-21: cyclophosphamide (350 mg/m2), doxorubicin (25 mg/m2), and vincristine (1 mg/m2) on day 1; prednisone (30 mg/m2) for 6 courses every 21 days.

Abbreviations: MGA, multidimensional geriatric assessment.

Treatment and Relative Dose of Chemotherapy

Fifty-four patients in group I (fit) received R-CHOP in 21-day cycles (R-CHOP-21). Twenty-two patients in group II (with comorbidities) received modified R-CHOP-21 (R-CDOP), with doxorubicin replaced by pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (LD) at 30 mg/m2 [25]. Fourteen frail patients received mini-CHOP-21, with reduced doses of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (1 patient allocated in group 3 died before starting treatment). All patients received recombinant human G-CSF in cases of febrile neutropenia or previously documented febrile neutropenia.

Radiotherapy for a bulky initial or residual mass was performed in all patients; salvage therapy was planned based on the physician's judgment.

The relative doses (RDs) of cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin were compared in the three groups at each cycle as: (actual dose in mg/body surface area (BSA) in m2)/(protocol-specified dose in mg/m2) × 100 [26]. The median RDs were compared in representative samples of the three groups, by comparing the proportions of patients who received the full dose (≥85% of the planned dose) using χ2 and Fisher's exact tests. The same approach was used to compare baseline characteristics by which patients achieved the full dose of the average RDs of cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin. Because in frail patients the planned dose was 50% of the standard dose by default, the delivered dose was compared with the planned 50% doses of the CHOP schedule.

Evaluation of Toxicity, Response, and Follow-Up

Adverse events were reported following the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0). Adverse events were defined as any adverse change from the patient's baseline condition after starting treatment, whether or not it was deemed to be associated with treatment. WHO grades for hematological toxicities were assessed from blood counts within treatment-specific nadir windows.

All patients underwent restaging after the end of treatment. Response was classified as a complete response or unconfirmed complete response (CR) or a partial response (PR), whereas stable disease and progressive disease were considered as no response, as stated by the International Workshop criteria [27].

Follow-up, which consisted of a physical examination, relevant laboratory tests (the same as those done for staging), and a total-body CT scan, was performed every 3 months during the first 2 years and every 6 months during year 3–5. The last follow-up was in August 2009.

Statistical analysis

Evaluation of the RD was made as described above. Descriptive analyses were performed for all evaluated variables. Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 and Fisher's exact tests. Overall survival (OS), event-free survival (EFS), and disease-free survival (DFS) (time to relapse in patients reaching CR) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method: survival curves were generated and compared using the log-rank test. A univariate analysis for survival was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Assessment of the proportional hazard assumption was carried out with Schoenfeld's residuals test. The following potential prognostic parameters were evaluated: sex, age, stage, IPI score, and group allocation, whereas rituximab use and comorbidities were not evaluated because of collinearity with group. Variables reaching statistical significance at a 90% level (p ≤ .1) on the univariate analysis were included in the regression model for the multivariate analysis.

Results

Identification of Groups According to MGA Score and Feasibility

The 91 enrolled patients were categorized according to MGA score into three groups. Group I (fit patients) included 54 patients, identified by a full ADL score (6), no grade 2 comorbidities or geriatric syndromes, and age <85 years, who received R-CHOP-21. Group II (patients with comorbidities) included 22 patients, identified by age <85 years, normal ADLs, no geriatric syndromes, and two or fewer comorbidities (grade 2), who received R-CDOP. Group III (frail patients) consisted of 15 patients, identified by age >85 years or at least one of the following conditions: ADL score <6, three or more grade 2 or one or more grade 3 comorbidities, and one or more geriatric syndromes. These patients were treated with the CHOP-21 schedule at reduced doses (50% of the standard for all the drugs), without rituximab (Tables 1 and 2). All senior hematologists and all nurses involved in the MGA were able to complete the testing on all 91 patients, including those with limited compliance who were aided by a caregiver. The median time to complete the MGA, including both the patient and health care professional portions, was 30 minutes.

Toxicity and Response

We observed four early treatment-related deaths (4.4%). Three were caused by infections (one in group I and two in group II) and one was caused by a myocardial infarction (in group III). One patient died before starting chemotherapy. Hematological and extrahematological toxicities were common, but only a few patients developed grade 3–4 toxicities. Severe extrahematological toxicities were characterized by infections and mucositis, whereas three patients in group II developed hand–foot dysesthesia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Major extrahematological and hematological toxicities (grade 3–4 according to the World Health Organization classification) observed in the 91 patients receiving tailored treatment

According to the intention-to-treat criteria, the overall response rate was 79% (67 CRs and five PRs). Three additional patients achieved a CR after second-line treatment. There were no statistical differences in the CR rate among the three groups. Details of responses are reported in supplemental online Table 1S.

Outcome

With a median follow-up of 57 months (range, 6–78 months), 42 patients were alive (31 in group I, seven in group II, and four in group III). Thirty-nine patients (43%) died as a result of lymphoma (19 in group I, 12 in group II, and eight in group III). The overall nonlymphoma mortality was 11%. Four patients (4.4%) died because of early treatment-related toxicity. Six patients died later while in CR: three as a result of a second cancer (one leukemia and two solid tumors) and three as a result of heart disease (myocardial infarction or heart failure).

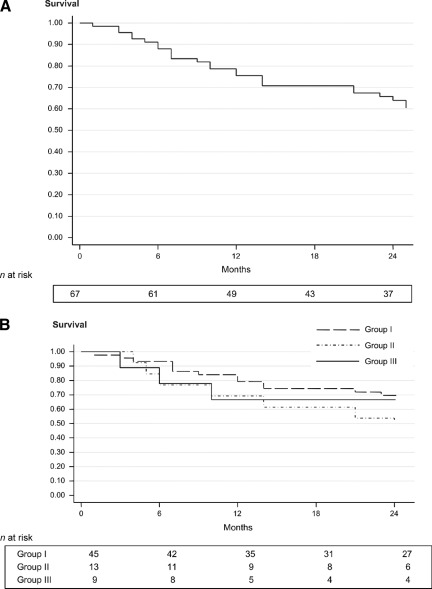

The median OS was 37 months in all patients. This was significantly better in group I than in group II (p = .0093) and in group III (p = .0033), without any statistical difference between group II and group III (p = .63) (Fig. 1). Among the 70 patients in first CR, 33 relapsed. Twenty-six received salvage treatment, with 13 achieving a second CR. At the last follow-up, 41 patients were alive and in CR. The DFS at 24 months was 64%, without statistical differences among the three groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Overall survival outcomes for all patients (A) and for patients according to group assignment (B).

Figure 2.

Disease-free survival outcomes for all patients (A) and for patients according to group assignment (B).

The 60-month EFS was 31%. This was significantly higher in group I than in group III (p = .001), and higher with borderline significance in group I than in group II (p = .088). No statistical difference was observed between group II and group III (Fig. 3). Univariate analysis revealed age >70 years and group allocation as significant factors predicting OS, but on multivariate analysis, group allocation was the only independent factor. In a subgroup analysis in patients aged ≥70 years, OS was significantly different in the three groups (p = .0265) (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Event-free survival outcomes for all patients (A) and for patients according to group assignment (B).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis for factors affecting outcome

Because only age >70 years and group allocation were significant for overall survival in the univariate analysis, these factors were included in the regression model for overall survival. In this model, the multivariate analysis showed that only group allocation remained as an independent and significant predictor of overall survival.

p < .05.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IPI, International Prognostic Index.

Discussion

Many clinical trials on NHL exclude elderly patients because of their advanced age and poor PS. In a Dutch registry study in NHL patients aged ≥70 years, only 26% received anthracycline-based chemotherapy [28]. In a more recent survey of 205 NHL patients aged >80 years [29], 87% had comorbidities and only 32% received anthracycline-based treatment. Apart from these retrospective data, the outcomes reported in recent trials in fit elderly patients with DLBCL [13, 14] cannot be considered representative of daily clinical practice in elderly patients with DLBCL.

Emerging data support the value of CGA in balancing the risks and benefits of treatment in elderly cancer patients. However, traditional CGAs are time-consuming and not routinely incorporated into oncology practice [30]. To date, studies using a CGA-based intervention are rare, and except for two reports, none address the setting of elderly patients with DLBCL [31, 32].

Our study tested the feasibility of implementing a simplified CGA in a cooperative group setting to tailor treatment to an unselected cohort of elderly DLBCL patients. Our results suggest that this approach is feasible and would allow the enrollment in future trials of a more representative population than those of studies including only fit patients aged 61–80 years [13, 14, 33]. Our study included both fit and frail DLBCL patients aged ≥65 years, without upper age limits, allowing us to prospectively test in daily clinical practice the feasibility and impact on OS outcomes of a tailored anthracycline-based treatment.

Categorization of patients into three groups using the MGA was easy and likely reduced the risk for undertreatment of fit patients and overtreatment of frail patients. The toxicity was acceptable, and long-term OS and EFS rates (46% and 31% at 5 years, respectively) were encouraging, comparing favorably with the recently updated GELA study that reported a 43.5% OS rate in a selected population aged 61–80 years [34].

Despite being slightly time-consuming, the CGA compares favorably with other apparently easier tools for assessing elderly patients, such as the abbreviated CGA proposed by Overcash et al. [35] and the self-administered CGA recently tested by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B and developed by Hurria et al. [36, 37], or even the Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 for identifying people with a higher degree of vulnerability, which was shown to be predictive for identifying impaired functional status, yet with weak correlation with comorbidity scales [38]. Our MGA was not self-administered, but it is easy and short, keeping an objective evaluation of elderly patients.

On the other hand, our results must take into account a number of study limitations: (a) low numbers of patients were included in group II and group III, requiring confirmation in a larger series; (b) assessment measures did not include a functional status examination using instrumental ADLs; (c) polypharmacy and nutritional status evaluation, psychological state, and social support were screened using a simplified questionnaire; and (d) patients unable to undergo treatment because of the absence of a caregiver were excluded, which is why the group of frail patients in our series is small and underestimates the real impact of frailty in patients aged ≥65 years.

The multivariate analysis showed group allocation to be the most important factor predicting the OS time, suggesting that the MGA score could be a better predictor than other factors (IPI, PS, age cutoff) in elderly DLBCL patients. In particular, because age >70 years has been emphasized as a strong predictor of inferior outcome in some trials [8, 9, 16, 39], our findings suggest prospectively comparing age cutoff with the MGA.

Our assumption that allocation to a risk group according to MGA score could, by itself, influence outcome through a modification of standard treatment remains a matter of debate, although the CR rate was not statistically different in the three groups. Patients in group III received 50% of the doses of the chemotherapy agents without rituximab. This could have worsened their outcome. However, the 2-year OS rate in this group was an unexpected 32%. Today, excluding frail DLBCL patients from rituximab-based therapy may be questionable, but at the time that this study was started these patients were usually candidates for palliative treatment. Frail patients were excluded from both the GELA trial [13] and the German trial, in which fit patients received CHOP on a 14-day schedule without rituximab [40]. Dose reduction in the CHOP schedule was successfully tested in a previous series of elderly DLBCL patients [41], and recently, promising results were reported with mini-CHOP plus rituximab in 150 fit elderly DLBCL patients aged >80 years [42]. So far, several frail patients are candidates for dose-adjusted anthracycline-based regimens including rituximab.

Regarding group II, standard R-CHOP was modified by introducing pegylated LD. Replacement of conventional doxorubicin with LD in the R-CHOP schedule was associated with a low rate of extrahematological toxicities, in particular cardiac and infectious complications. Moreover LD (pegylated and nonpegylated) has achieved encouraging results in DLBCL patients [43, 44]. R-CDOP with pegylated LD at a dose of 30 mg/m2 achieved a 76% response rate and 65% 2- year EFS rate in elderly DLBCL patients without treatment-related mortality [25]. Similar encouraging results were reported in patients with impaired cardiac function or preexisting cardiac risk factors [45]. Therefore, replacing conventional doxorubicin with LD seems an efficient alternative in the treatment of patients with preexisting cardiac dysfunction.

Although MGA can easily discriminate fit from frail patients, it could be troublesome to identify patients in group II. This group included patients with a median age intermediate between that of group I and group III. They were functionally independent and without geriatric syndromes, but many had one or more serious cardiac comorbidities, indirectly confirming the importance of comorbidities as an independent risk factor, as previously reported [46, 47].

In conclusion, this approach confirms that a tailored strategy in an unselected population of elderly DLBCL patients, which represents daily clinical practice, is feasible and achieved encouraging outcomes. However, larger series of patients to be included in the group II and group III are needed in order to confirm our data.

See www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank AIL ONLUS Ancona for economic support.

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- Consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

- (SAB)

- Scientific advisory board

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Attilio Olivieri, Guido Gini, Mauro Montanari, Marino Brunori, Pietro Leoni

Provision of study material or patients: Attilio Olivieri, Guido Gini, Mauro Montanari, Giuseppe Visani, Marino Brunori, Barbara Guiducci, Massimo Catarini, Massimo Marcellini, Luciano Giuliodori, Francesco Alesiani, Antonella Poloni

Collection and/or assembly of data: Attilio Olivieri, Guido Gini, Caterina Bocci, Mauro Montanari, Silvia Trappolini, Jacopo Olivieri, Giuseppe Visani, Alessandro Isidori, Marino Brunori, Barbara Guiducci, Massimo Catarini, Massimo Marcellini, Luciano Giuliodori, Francesco Alesiani, Antonella Poloni

Data analysis and interpretation: Attilio Olivieri, Guido Gini, Caterina Bocci, Jacopo Olivieri

Manuscript writing: Attilio Olivieri, Guido Gini, Caterina Bocci, Silvia Trappolini, Jacopo Olivieri

Final approval of manuscript: Attilio Olivieri, Guido Gini, Pietro Leoni

References

- 1.Balducci L, Extermann M. Cancer and aging. An evolving panorama. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balducci L, Beghe C. Cancer and age in the USA. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;37:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olivieri A, Capelli D, Montanari M, et al. Very low toxicity and good quality of life in 48 elderly patients autotransplanted for hematological malignancies: A single center experience. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:1189–1195. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olivieri A, Santini G, Patti C, et al. Upfront high-dose sequential therapy (HDS) versus VACOP-B with or without HDS in aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Long-term results by the NHLCSG. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1941–1948. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jantunen E, Mahlamäki E, Nousiainen T. Feasibility and toxicity of high-dose chemotherapy supported by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in elderly patients (≥60 years) with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Comparison with patients <60 years treated within the same protocol. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:737–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jantunen E, Canals C, Rambaldi A, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients (≥60 years) with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: An analysis based on data in the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation registry. Haematologica. 2008;93:1837–1842. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliansky DM, Czuczman M, Fisher RI, et al. The role of cytotoxic therapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the treatment of diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Update of the 2001 evidence-based review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:20–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gómez H, Mas L, Casanova L, et al. Elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: Identification of two age subgroups with differing hematologic toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2352–2358. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gómez H, Hidalgo M, Casanova L, et al. Risk factors for treatment-related death in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Results of a multivariate analysis. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2065–2069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, et al. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1002–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304083281404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5027–5033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: A randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:105–116. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Extermann MS, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1824–1831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balducci L, Extermann M. Management of cancer in the older person: A practical approach. The Oncologist. 2000;5:224–237. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-3-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balducci L. Management of cancer in the elderly. Oncology (Williston Park) 2006;20:135–143. discussion 144, 136, 151–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pileri SA, Leoncini L, Falini B. Revised European-American lymphoma classification. Curr Opin Oncol. 1995;7:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Non-Hodgkins' Lymphoma Classification Project. A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997;89:3909–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cockrell JR, Folstein MF. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmelee PA, Thuras PD, Katz IR, et al. Validation of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale in a geriatric residential population. J Am Geriatric Soc. 1995;43:130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winograd CH, Gerety MB, Chung M, et al. Screening for frailty: Criteria and predictors of outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:778–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balducci L, Extermann M. Management of the frail person with advanced cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;33:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(99)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaja F, Tomadini V, Zaccaria A, et al. CHOP-rituximab with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymph. 2006;47:2174–2180. doi: 10.1080/10428190600799946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epelbaum R, Haim N, Ben-Shahar M, et al. Dose intensity analysis for CHOP chemotherapy in diffuse aggressive large cell lymphoma. Isr J Med Sci. 1990;24:533–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maartense E, Hermans J, Kluin-Nelemans JC, et al. Elderly patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Population-based results in The Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1219–1227. doi: 10.1023/a:1008485722472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thieblemont C, Grossoeuvre A, Houot R, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in very elderly patients over 80 years. A descriptive analysis of clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:774–779. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfreundschuh M. How I treat elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:5103–5110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-259333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernardi D, Milan I, Balzarotti M, et al. Comprehensive geriatric evaluation in elderly patients with lymphoma: Feasibility of a patient-tailored treatment plan. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:754–755. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tucci A, Ferrari S, Bottelli C, et al. A comprehensive geriatric assessment is more effective than clinical judgment to identify elderly diffuse large cell lymphoma patients who benefit from aggressive therapy. Cancer. 2009;115:4547–4553. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–3127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: A study by Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Overcash JA, Beckstead J, Extermann M, et al. The abbreviated comprehensive geriatric assessment (aCGA): A retrospective analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;54:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: A feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104:1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, et al. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1290–1296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: A tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691–1699. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Advani RH, Chen H, Habermann TH, et al. Comparison of conventional prognostic indices in patients older than 60 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP in the US Intergroup Study (ECOG 4494, CALGB 9793): consideration of age greater than 70 years in an elderly prognostic index (E-IPI) Br J Haematol. 2010;151:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfreundschuh M, Trm̈per L, Kloess M, et al. German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group. Two-weekly or 3-weekly CHOP chemotherapy with or without etoposide for the treatment of elderly patients with aggressive lymphomas: Results of the NHL-B2 trial of the DSHNHL. Blood. 2004;104:634–641. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shikama N, Oguchi M, Isobe K, et al. A prospective study of reduced-dose three-course CHOP followed by involved-field radiotherapy for patients 70 years old or more with localized aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peyrade F, Jardin F, Thieblemont C, et al. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) investigators. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:460–468. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luminari S, Montanini A, Caballero D, et al. Nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Myocet™) combination (R-COMP) chemotherapy in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): Results from the phase II EUR018 trial. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1492–1499. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avilés A, Neri N, Castañeda C, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination chemotherapy in the treatment of previously untreated aggressive diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2002;19:55–58. doi: 10.1385/MO:19:1:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitt CJ, Dietrich S, Ho AD, et al. Replacement of conventional doxorubicin by pegylated liposomal doxorubicin is a safe and effective alternative in the treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients with cardiac risk factors. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:391–397. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1308-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, et al. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janssen-Heijnen ML, Van Spronsen DJ, Lemmens VE, et al. A population-based study of severity of comorbidity among patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Prognostic impact independent of International Prognostic Index. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:597–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.