Summary

The somitic compartment that gives rise to trunk muscle and dermis in amniotes is an epithelial sheet on the external surface of the somite, and is known as the dermomyotome. However, despite its central role in the development of the trunk and limbs, the evolutionary history of the dermomyotome and its role in non-amniotes is poorly understood. We have tested whether a tissue with the morphological and molecular characteristics of a dermomyotome exists in non-amniotes. We show that representatives of the agnathans and of all major clades of gnathostomes each have a layer of cells on the surface of the somite, external to the embryonic myotome. These external cells do not show any signs of terminal myogenic or dermogenic differentiation. Moreover, in the embryos of bony fishes as diverse as sturgeons (Chondrostei) and zebrafish (Teleostei) this layer of cells expresses the pax 3 and 7 genes that mark myogenic precursors. Some of the pax7-expressing cells also express the differentiation-promoting myogenic regulatory factor Myogenin and appear to enter into the myotome. We therefore suggest that the dermomyotome is an ancient and conserved structure that evolved prior to the last common ancestor of all vertebrates. The identification of a dermomyotome in fish makes it possible to apply the powerful cellular and genetic approaches available in zebrafish to the understanding of this key developmental structure.

Keywords: myogenesis, dermomyotome, dermatome, dermis, phylogeny, vertebrate, muscle, fish

Introduction

Rapid movement is a characteristic of animal life that became possible with the evolution of striated muscle. As the deuterostome lineage gave rise to vertebrates, most striated muscle became anchored to the newly evolved endoskeleton, innervated by central motor neurons and responsible for voluntary movement. In vertebrates, most skeletal muscle begins to develop during maturation of the somites. The somites themselves are transient embryonic structures located in pairs on either side of the axial organs. They arise from the rostro-caudally progressing segmentation of the trunk paraxial mesoderm. The somites of most vertebrates form as blocks of tissue with an epithelial coating (epithelial somite) and a space in the centre, the somitocoel, which may contain a loose meshwork of cells. During amniote somite maturation, a ventral part of the epithelial somite delaminates into the mesenchymal sclerotome, whereas dorsal cells retain their epithelial nature. This dorsal portion is referred to as the dermomyotome and, as well as being the origin of trunk and limb skeletal muscle, is also the source of other mesodermal tissues in the amniote body, including dermis and vascular endothelia. Thus, the dermomyotome is a multipotent tissue important for the development of skin, blood vessels, and the striated muscles responsible for voluntary movement (Buckingham et al., 2003; Olivera-Martinez et al., 2004; Scaal and Christ, 2004).

In amniotes, the four edges of the dermomyotome (the dorsomedial, ventrolateral, rostral, and caudal dermomyotome lips) are the main sources of early myogenic cells that translocate underneath the dermomyotome epithelium and lead to growth of the myotome (the first skeletal muscle fibers in the body). At these lips, the dermomyotome epithelium curls inward, cells leave the dermomyotome, enter the myotome and elongate into muscle fibers. New muscle fibers are added progressively at the edges of the myotome until the dermomyotome is fully de-epithelialized (Ben-Yair et al., 2003; Denetclaw and Ordahl, 2000; Kahane et al., 2001). Cells from the ventrolateral lip also delaminate and migrate laterally to yield muscle in the limb buds and ventral body wall. Thus, the dermomyotome is the source of myogenic cells in the trunk and limbs of amniotes (see Tajbakhsh, 2003).

The dermomyotome also contributes to other tissues. Studies of dermis development in chick and mouse indicate that in both, dermal progenitors de-epithelialize from distinct dermomyotome regions, particularly the central sheet, to form the subectodermal mesenchyme before differentiating into distinct areas of the dorsal dermis (Ben-Yair and Kalcheim, 2005). Angiogenic cells from the dermomyotome form the walls of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels in the dermis, the body wall and the limb buds of amniote embryos (He et al., 2003; Kardon et al., 2002). Myogenic precursors responsible for post-natal growth and muscle repair also derive from the somite, presumably from the dermomyotome (Armand et al., 1983). It is unclear when during development dermomyotome cells become restricted to the generation of one of these fates (Huang and Christ, 2000; Scaal and Christ, 2004).

The above model for development of dermomyotome into myotome, dermis, and other cell types has largely been elucidated in a few ‘model’ amniotes. In many teleosts, myogenic differentiation begins at much earlier stages of development, relative to its commencement in amniotes. Myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs: myf5, myoD or myogenin) and Myosin Heavy Chain genes are expressed prior to segmentation in cells adjacent to the notochord, called adaxial cells (Coutelle et al., 2001; Kobiyama et al., 1998; Rescan, 2001; Weinberg et al., 1996). In zebrafish (Danio rerio), around the time of incorporation into a somite, adaxial cells begin to differentiate into elongated muscle fibers, dependent on midline-derived Hedgehog signaling. During this elongation, adaxial cells move laterally to form a monolayer of mononucleated embryonic slow muscle fibers located superficially on the somite (Devoto et al., 1996). Following the movement of slow muscle precursors to the surface of the somite, deeper cells differentiate as fast muscle fibers (Blagden et al., 1997; Henry and Amacher, 2004). Similar movement of adaxial cells probably occurs in other teleosts, based on histological and gene expression studies (e.g. pearlfish and trout, Rescan et al., 2001; Stoiber et al., 1998). The development of a primary myotome prior to the establishment of a dermomyotome in amniotes may be analogous to the development of adaxial cells in teleosts (Kalcheim et al., 1999).

After this embryonic phase of myogenesis, several phases of muscle growth have been defined in teleosts. During stratified hyperplasia, new muscle fibers form either solely at the dorsal and ventral extremes of the myotome, or in addition in a layer between the superficial muscle layer and the deeper fast fibers (Rowlerson and Veggetti, 2001). Subsequently, mosaic hyperplasia is distributed throughout the myotome suggesting that myogenic precursors are resident within the tissue, as is the case with amniote satellite cells (Rowlerson and Veggetti, 2001). The distinctions between embryonic, stratified, and mosaic hyperplasia suggest that there may be several distinct mechanisms for developing muscle fibers in teleosts. The distinct mechanisms of myf5 induction in numerous regions of the mouse somite suggest that amniotes also have several modes of somitic myogenesis analogous to stratified hyperplasia (Hadchouel et al., 2003). Moreover, the classical description of secondary fiber formation in amniotes is analogous to mosaic hyperplasia (Kelly and Rubinstein, 1980). Thus, fish myogenesis has numerous similarities to that in amniotes.

The role of a dermomyotome in non-amniote myotome and dermis development has been generally ignored in recent years, simply because it has been taken for granted that a dermomyotome (sensu amniotes) does not occur in these animals (Hollway and Currie, 2003; but see also Kaestner, 1892; Sporle, 2001; Stickney et al., 2000). Modern work on zebrafish has occasionally used the term dermomyotome to refer to the non-sclerotome compartment of the somite (Nornes et al., 1996; Schvarzstein et al., 1999), but there has been no evidence suggesting a layer of myogenic cells external to the embryonic myotome homologous to the amniote dermomyotome. We combine new research with a critical re-evaluation of published work to test whether the dermomyotome is conserved through all vertebrates, including teleosts. We first outline briefly the evolutionary origins of the dermomyotome in vertebrates, and then explore the evolution and function of the dermomyotome in non-amniote vertebrates. We discuss evidence that cells previously called ‘external cells’ in teleosts have the morphological and molecular characteristics of a dermomyotome. We suggest that study of the teleost dermomyotome may shed light on the cellular and genetic basis for the development of dermomyotome form. Finally, we discuss the implications of the inclusion of non-tetrapod vertebrates for understanding the evolution of dermomyotome function in vertebrates.

Dawn of the dermomyotome

The primary ancestral function of mesoderm was likely myogenesis because skeletal, cardiac and smooth muscles are major derivatives of mesoderm in both protostomes and deuterostomes. In most metazoans, there are two (or more) phases of myogenesis, with myogenesis during larval growth occurring from cells ‘set aside’ during earlier embryonic development: two phases of myogenesis has been proposed as a basal bilaterian character (Peterson et al., 1997). It is unclear whether the earliest chordate larvae had a large myogenic precursor population. Extant urochordate larvae have unsegmented tail mesoderm that is primarily one type of skeletal muscle flanking a stiffened rod-like notochord, and urochordates are small with little significant muscle growth prior to metamorphosis (Jeffery and Swalla, 1997). During the evolution of chordates, a segmented mesoderm yielded somite-derived cartilage and tendon cells in addition to muscle. Thus, the somites became specialized for production of the musculoskeletal system of trunk and tail.

The life history and size of the earliest chordates is unknown, however, it is clear that muscle growth became quite significant in chordates. In cephalochordates and vertebrates, muscle growth persists beyond embryogenesis, suggesting that some myogenic cells must have been reserved for later myogenesis. In extant segmented cephalochordates like amphioxus, two kinds of muscle form in the anterior segments: slow muscle fibers are located superficially and fast muscle fibers are located deep in the myotome, just as in teleosts (Lacalli and Kelly, 1999). Although extant cephalochordates may have diverged considerably from the main vertebrate lineage, the fact that early myogenesis is similar in cephalochordates and teleosts suggests that the common ancestor already had rather sophisticated myogenesis. Like amphioxus, vertebrates form several early populations of myotomal muscle fibers (reviewed in Bone, 1978) and muscle growth and repair continues throughout life. This raises the possibility that in all chordates, the somites contain not only precursors to early embryonic myogenesis, but also populations of myogenic stem cells underlying later muscle growth.

Agnathans from the Lower Cambrian reveal that early vertebrates could be large, requiring significant post-embryonic muscle growth (Shu et al., 1999). In contrast to cephalochordates, where no late myogenic cells have been described, cells similar to the dermomyotome may be present in the lamprey, a representative of agnathan vertebrates (Fig. 1). A lamprey has stacks of muscle lamella similar to those in amphioxus (Maurer, 1906). The 26-day lamprey tail also has a distinct layer of ‘undifferentiated’ cells on the external surface of the myotome underlying the ectoderm (Fig. 2A, from Nakao, 1977). These ‘external cells’ are sparsely distributed, forming an extremely thin layer of cells on the surface of the myotome. These cells are not muscle, as revealed by their lack of myofibrils; we suggest that they are multipotent precursor cells.

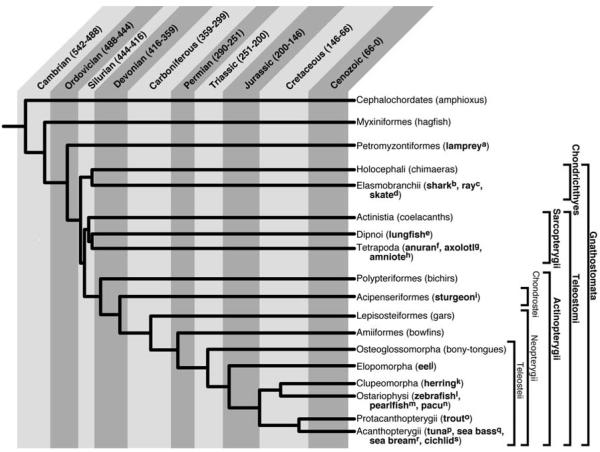

1. Phylogenetic relationships among selected groups of extant vertebrates. Cladogram is based on Helfman et al., 1997. with some modifications based on recent analysis of the evolutionary relationships between Petromyzontiformes, Myxiniformes, and the Gnathostomata (Furlong and Holland, 2002; Takezaki et al., 2004). The time of divergence between groups is approximately indicated (Stiassny, et al., 2004). In embryos of all the animals listed in bold there is evidence of a layer of undifferentiated cells external to the embryonic myotome. Selected references for each are as follows:

aMaurer, 1894; Nakao, 1977; see Fig. 2A

cKaestner, 1892; Maurer, 1894; Sunier, 1911

dSunier, 1911; see Figs. 2B, C

gTajbakhsh, 2003; see Fig. 2E

hMaurer, 1894; Grimaldi et al., 2004, see Fig. 2D

iMaurer, 1894; see Fig. 3A, 4A

jSunier, 1911; see Fig. 3B

lWaterman, 1969; see Fig. 4B-D, F

mStoiber et al., 1998; Fig. 3C

oMaurer, 1894; Vialleton, 1902; see Figs. 3E, F

pSee Fig. 3D

rLopez-Albors et al., 1998; Ramirez-Zarzosa et al., 1995

sSee Fig. 4E

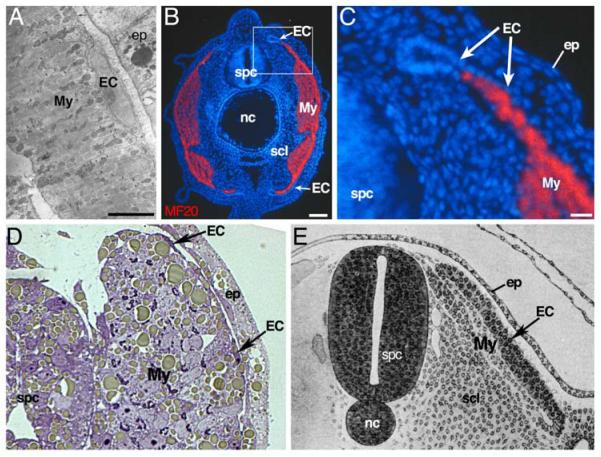

2. Representative agnathan, chondrichthyan and sarcopterygian embryos each have a layer of undifferentiated cells external to the myotome.

A. External cells in a lamprey, Lampetra japonica. Electron micrograph of a transverse section of a midtrunk myotome of a 5-day lamprey (modified from Nakao, 1977). The myotome is composed of horizontal muscle lamellae, bounded on the lateral surface by undifferentiated external cells which are separated from the epidermis by a large extracellular space containing basal lamina (thick arrow). Scale bar = 5 μm

B. External cells in a skate Raja erinacea: transverse section of the anterior tail of an embryo. The myotome is immunolabeled with the MF20 myosin antibody (red), and nuclei with Hoechst 33258 (blue). An apparent epithelial cell layer external to the myotome does not express myosin at this time. Scale bar = 100 μm.

C. High magnification view of boxed area in B. The external cells form structures similar to the dorsomedial and ventrolateral lips of the amniote dermomyotome. Scale bar = 25 μm.

D. External cells in Xenopus sp. Transverse section of somite 8 in a stage 35 tadpole (modified from Grimaldi et al., 2004). External to the myotome is a thin layer of external cells.

E. ’External cells’ in a chick, Gallus gallus: drawing of transverse section through the trunk of an embryo (modified from Lillie, 1919). The chick somite begins as an epithelial sphere and then de-epithelializes as it becomes subdivided into sclerotome, myotome, and an epithelial layer external to the myotome. This epithelial layer was called the dermatome by early investigators, but is now known as the dermomyotome; we have labeled it ‘external cells’ to emphasize its similarity to other vertebrates.

EC, external cells; My, myotome; ep, epidermis; scl, sclerotome; spc, spinal cord; nc, notochord.

To address whether undifferentiated cells external to the embryonic myotome are evolutionarily widespread, we examined embryos of the skate Raja erinacea, an elasmobranch example of the chondrichthyan branch of gnathostome diversity (Fig. 1). We used a pan-myosin antibody to label the primary myotome and found that there is a layer of somite cells external to the primary myotome (Fig. 2B). This external cell layer is curled inward at its dorsomedial and ventrolateral edges (Fig. 2C), forming structures strikingly similar to the dorsomedial and ventrolateral lips of the dermomyotome in amniotes (Fig. 2E). Available molecular markers do not allow us to determine if the cells between the external cell layer and the epidermis are neural crest cells or the beginning of the skate dermis.

In addition to amniotes, embryos of other sarcopterygians have external cells (Sunier, 1911). In embryos of the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, Hamilton (1969) described a ‘dermatome’ as a thickened epithelial veil hanging over the myotome. The thickness of the Xenopus external cell layer varies according to the stage of development and the anterior-posterior position in the embryo; it can be a structure morphologically similar to the cuboidal epithelial monolayer in amniotes and skates, or a very thin squamous epithelium more similar to that seen in lampreys (Fig. 2D, Grimaldi et al., 2004). At dorsomedial and ventrolateral extremes this layer expresses myogenic markers as it curls inward in a manner similar to amniote dermomyotome and skate (Grimaldi et al., 2004). Thin external cells have also been described in lungfish, a non-tetrapod representative of the sarcopterygians (Maurer, 1906). Thus, representatives of the agnathan vertebrates, chondrichthyans and sarcopterygians all have a layer of undifferentiated cells external to the embryonic myotome. In the amniotes, this external cell layer is the dermomyotome. The simplest interpretation of the similar position, morphology and lack of myosin labeling is that a dermomyotome epithelium is a shared, ancestral vertebrate characteristic. This begs the question: what happened to the dermomyotome in actinopterygians, the sister group to the sarcopterygians (Fig. 1)?

External cells in ray-finned fishes: topological dermomyotome

To test whether the external cell layer is a primitive characteristic in actinopterygians, we have examined sturgeon (Acipenser ruthens), which, as a chondrostean, exemplifies a clade rooted close to the base of the modern actinopterygian radiation. Sturgeons, like most teleosts, have an embryonic myotome consisting of distinguishable superficial (presumed slow) and deep (presumed fast) fibers (Bone, 1978; Flood et al., 1987; Flood and Kryvi, 1982). On the external surface of this embryonic myotome is a thin layer of cells very similar to the external cells of lamprey (above) and anurans (Fig. 3A, compare to Fig. 2A, D, Grimaldi et al., 2004). These external cells do not show any characters of differentiated muscle visible in the electron microscope, and are not labeled by pan-myosin immunolabeling (P.S. and W.S., unpublished).

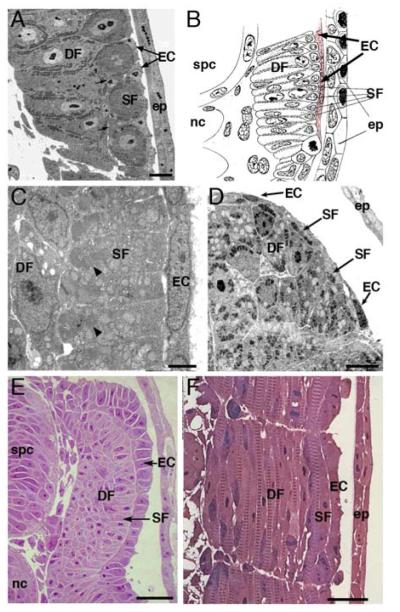

3. Actinopterygian embryos have a layer of undifferentiated cells external to the myotome. All species examined have two layers of differentiated muscle fibers: superficial and deep.

A. External cells in the sturgeon Acipenser ruthenus. Semi-thin transverse section posterior to the anal vent of an embryo at hatching (at least 60 somites). External to the superficial fibers is a layer of thin external cells. Scale bar = 2 μm.

B. External cells in an eel Muraena sp. Transverse section of 5 days old embryo; drawing modified from (modified from Sunier, 1911). A layer of external cells (pale red) is clearly attached to the myotome and separated from the epidermis.

C. External cells in the pearlfish Rutilus frisii meidingeri. Electron micrograph of a segment of the dorsolateral surface of the myotome in a transverse section of a 40 somite stage embryo. External cells form a very thin squamous epithelium and show no evidence of myogenic differentiation. Scale bar = 2 μm.

D. External cells in the yellowfin tuna Thunnus albacares. Transverse section of an epaxial quadrant from an embryo at hatching (21 hrs post fertilization). Some flattened ECs are present at the lateral surface of the myotome. Superficial fibers are very small in size and arranged in a discontinuous layer. Scale bar = 5 μm.

E. External cells in trout Salmo trutta. Semi-thin transverse section just posterior to the anal vent of an eyed stage trout embryo (55-60 somites). External cells lie over the superficial fibers as in other actinopterygians. However, the cells form an apparent cuboidal epithelium more similar to the external layer in skate (Fig. 1B) and chick (Figure 1C). Scale bar = 25 μm.

F. External cells in trout are not elongated and do not show any indications of myogenic differentiation. Semi-thin horizontal section of an eyed stage trout (55-60 somites), just posterior to the anal vent. Superficial and deep fibers have clear myofibril striations. No myofibrils or any other signs of differentiation are found in external cells. Scale bar = 25 μm.

EC, external cells; DF, deep fibers; SF, superficial fibers, scl; sclerotome; spc, spinal cord; nc, notochord; ep, epidermis

External cells are present not only in non-teleost actinopterygians. A transient population of undifferentiated external cells has been found in diverse teleosts (summarized in Fig. 1), including herring (Clupea harengus, Johnston, 1993), eel (Muraena sp., Fig. 3B, modified from Sunier, 1911), pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus, Dal Pai-Silva et al., 2003), sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax, Veggetti et al., 1990) and sea bream (Sparus aurata, Patruno et al., 1998; Ramirez-Zarzosa et al., 1995). External cells have been most thoroughly characterized in zebrafish, where they are present from the end of segmentation to at least the newly hatched larva (Waterman, 1969). In electron micrographs, external cells are extremely flattened cells on the external surface of the primary myotome. They do not show any characteristics of immature muscle fibers, such as myofibrils or clusters of filaments and ribosomes. External cells overlap each other and there may be specialized junctions between adjacent external cells (Waterman, 1969). We have re-examined zebrafish external cells by electron microscopy and confirmed Waterman’s characterization (Groves et al. 2005 and W.S., unpublished). Although described previously, external cells in these fish species have not been recognized as homologous to the dermomyotome of tetrapods.

Zebrafish are highly derived cyprinid teleosts, raising the possibility that the flattened external cells in this species are not an ancestral characteristic, but an evolutionary novelty. Another cyprinid, the pearlfish (Rutilus frisii meidingeri) has flattened external cells similar to those of zebrafish shortly after the end of segmentation. Pearlfish external cells form an apparently squamous epithelial layer closely apposed to the primary myotome but clearly separated from the epidermis (Fig. 3C). Thus, both cyprinids for which there is reliable histological information have a thin layer of external cells outside of the embryonic myotome. It is not clear how many of the over 2000 other cyprinid species are similar.

Flattened external cells are not unique to cyprinids. The very distantly related yellow fin tuna is a scombroid percomorph teleost that attains a large adult size. Like sturgeon, eel and the cyprinids, tuna embryos have a continuous layer of extremely thin cells on the external surface of superficial muscle fibers, similar to that in some stages of Xenopus (Fig. 2D, Grimaldi et al., 2004). On the other hand, the trout external cell layer is a robust, apparently cuboidal epithelium (Fig. 3E, F), much more similar to that in the chondrichthyan skate (Fig. 2B, C) and sarcopterygian chick (Fig. 2E). Cichlids, illustrated by Astatotilapia burtoni, a labroid percomorph teleost, also have a robust external cell layer (see Figure 4E). Nevertheless, the embryonic myotome of these teleosts is similar to that in cyprinids, with a superficial layer of small diameter (presumably slow) fibers and a deeper mass of larger diameter (presumably fast) fibers that grow by stratified hyperplasia (E.G.A. and S.H.D., unpublished, Rescan et al., 2001; Rowlerson and Veggetti, 2001). Thus, it is probably a general characteristic of teleosts to have an apparently myogenic external cell layer, but the thickness of this layer is not conserved phylogenetically.

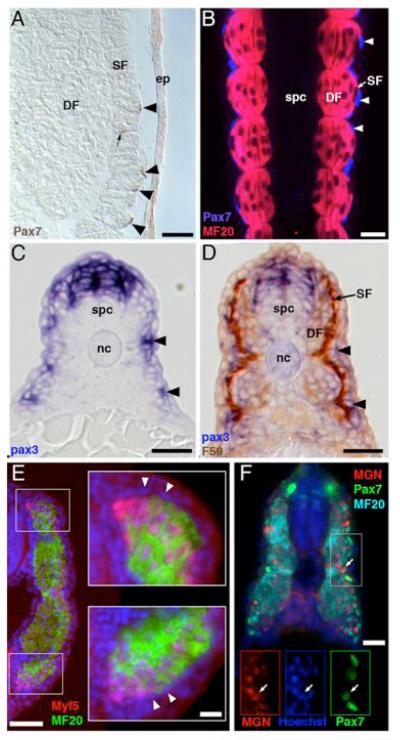

4. Cells external to the embryonic myotome express myogenic pax genes in actinopterygians

A. Sturgeon, Acipenser ruthenus, larva, 14 days posthatching. Pax7-positive cells (arrows) external to, and inserted between, the superficial dorsal myotome fibers in near the anal vent, revealed with a Pax7 antibody (brown, DSHB). Note that the stained cells are at positions similar to those of the external cells in Fig. 3A. Scale bar, 25 μm.

B. Pax7-positive, myosin-negative cells have the same distribution as external cells in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Zebrafish embryos at the end of segmentation (24h) were double labeled with Pax7 antibody (blue, arrowhead) and a myosin antibody (MF20, red) and optically sectioned in the horizontal plane by confocal microscopy. Pax7-positive nuclei are external to the superficial muscle fibers of the myotome, which are distinguished from the multinucleated deep fibers by being mononucleated. Scale bar, 25μm.

C. pax3 is expressed in somitic cells on the external surface of the zebrafish myotome (arrowheads). Embryos at the end of the segmentation period (24h) were labeled for pax3 (Seo et al., 1998) in whole mount by in situ hybridization and then sectioned transversely. pax3 is also expressed in the dorsal neural tube. Scale bar, 25μm.

D. pax3-expressing somitic cells (purple, arrowheads) in zebrafish are external to the myotome and do not express the superficial muscle marker slow myosin (F59 antibody, brown). Scale bar, 25μm.

E. Myf5-expressing cells are subjacent to the external cell layer in cichlid embryos. Cichlid (Astatotilapia burtoni) embryos at the early pectoral fin bud stage were fixed, and transverse sections from the tail were labeled with antibodies to myosin (MF20, green) and to myf5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, green), nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). External cells form a continuous layer surrounding the MF20-labeled myotome. Myf5 is expressed in myotomal cells subjacent to the dorsomedial and ventral tips of the external layer. Compare to figure 2B, C, E. Scale bar, 50 μm; inset, 10 μm.

F. Pax7 and Myogenin are co-expressed in zebrafish. Zebrafish embryos at the end of segmentation (24h) were sectioned and labeled with antibodies against Myogenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, green), Pax7, and myosin (MF20, cyan). Myogenin is expressed in cells in the lateral portion of the myotome, the most lateral of which co-express Myogenin and Pax7. Scale bar, 25 μm.

SF, superficial fibers; DF, deep fibers; spc, spinal cord; nc, notochord; ep, epidermis.

In summary, representatives of all extant vertebrate taxa have a layer of non-muscle cells on the external surface of the embryonic myotome (Fig. 1). The thickness of this external cell layer varies considerably between species and developmental stages, and fails to correlate with evolutionary relationships or adult body size.

Molecular characteristics of the external cell layer

If the external cell layer in non-amniotes and the dermomyotome of amniotes are homologous, they should express similar sets of genes. Fortunately, teleosts, and especially zebrafish, are now open to a level of molecular genetic and manipulative embryology comparable with that in amniotes. As discussed above, neither external cells nor dermomyotome cells express myogenic differentiation markers such as myosin. Myogenic precursors in the amniote dermomyotome express either or both the pax3 and pax7 genes, each of which is required for normal myogenesis (Pownall et al., 2002). Pax3 is required for migration of myogenic precursors into the limb bud, and Pax7 is required for the normal development of postnatal myogenic precursors (Oustanina et al., 2004; Seale et al., 2000). Recently, the external cell layer of Xenopus was shown to express pax3 throughout most of its dorso-ventral extent, and MRFs Myf5 and MyoD near the dorsal and ventral tips of the myotome and elsewhere (Grimaldi et al., 2004). Thus, in the amphibian Xenopus, external cells are likely to include myogenic precursors. The lamprey also expresses Pax3/7 in cells on the external layer of the embryonic myotome, with particularly strong expression near the dorsal and ventral tips, suggesting that external cells include myogenic precursors in agnathans (Kusakabe and Kuratani, personal communication). In early diverging, ancestral actinopterygians such as the sturgeon, a Pax7 antibody labels nuclei in flattened cells on the external surface of the somite, suggesting that sturgeon external cells include myogenic precursors (Fig. 4A). Sturgeon has in addition some Pax7-positive nuclei deeper in the myotome, on the surface of differentiating cells. Whether these cells are similar to myogenic precursors of amniote satellite cells (Seale et al., 2000) or have another fate remains to be determined. In zebrafish, pax3 and pax7 mRNAs are expressed sequentially in the somites (Seo et al., 1998). The Pax7 antibody strongly labels the nuclei of cells on the surface of the somite (Fig. 4B). Some of these nuclei are flattened round nuclei over the external surface of the central part of the somite. Pax3 mRNA is also expressed in cells external to the superficial monolayer of the myotome, but still apparently within the somite (Fig. 4C, D and Groves et al., 2005). Pax3 mRNA is expressed prior to pax7 mRNA (Seo et al., 1998 and data not shown), this may in part explain why there appear to be more pax3 positive cells. The morphology and distribution of these pax3 and pax7 expressing cells is similar to the external cells, suggesting that external cells in zebrafish include myogenic precursors. As in Xenopus and amniotes, the pax3 and pax7 expressing cells cover the entire dorsoventral extent of the embryonic myotome. Other Pax7 positive cells have elongated nuclei within the horizontal or transverse septa, which may be within migrating external cells.

We examined the expression of Myf5 and Myogenin to identify specified myogenic precursors. In a cichlid, Astatotilapia sp., Myf5 is expressed most strongly in cells at the dorsal and ventral tips of the myotome, subjacent to the external cell layer (Fig. 4E), In zebrafish, Myogenin is expressed in cells at the dorsal and ventral tips of the myotome, but also in cells in the lateral third of the myotome. Some of the most lateral cells expressing Myogenin also express Pax7, suggesting that Pax7-expressing external cells are myogenic (Fig. 4F).

Dermal precursors begin to express collagen genes while they are still part of the dermomyotome. In both Xenopus and trout, col1a1 is expressed in dermis and also in external cells, suggesting that external cells share with the amniote dermomyotome the property of including dermal precursors (Grimaldi et al., 2004; Rescan et al., 2005). Similarly, in zebrafish, cells within the somite but external to the superficial slow muscle layer express col1a2 (Le Guellec et al., 2004; Sire and Akimenko, 2004).

In conclusion, our analysis of pax3, Pax7, Myf5, and Myogenin expression suggests that the external cell layer includes myogenic precursors, while the expression of collagen suggests that the external cell layer includes dermal precursors. Gene expression analysis supports a homology between amniote dermomyotome and teleost external cells.

Conservation of the dermomyotome

We propose that the dermomyotome is an evolutionarily ancient structure that is conserved in all vertebrates. Representatives of all vertebrate taxa have a layer of undifferentiated cells external to the embryonic myotome. This external cell layer is a robust cuboidal epithelium in at least one representative of three major gnathostome clades: chondrichthyans (skate), sarcopterygians (chick), and actinopterygians (trout). We have also shown that actinopterygians share with tetrapods the expression of Pax3 and Pax7 in the external dermomyotomal cell layer. Finally, we have shown that MRF genes are expressed in some of these cells. Below we discuss the practical and evolutionary issues that are raised by the realization that the dermomyotome evolved prior to the radiation of the vertebrates, and has been conserved in teleosts.

The dermomyotome and myogenesis

The basic cellular mechanism that generates the primary, embryonic myotome is quite similar in all vertebrates that have been examined. In several well-characterized species, including some teleosts, amniotes, and amphibians, myotome formation has been described as a multistage process. Paraxial mesoderm cells closest to the dorsal midline are the first cells to express MRFs; in quail, Xenopus, and zebrafish, myf5 is expressed in the medial cells of the still fully epithelial somite (Pownall et al., 2002). These medial cells probably give rise to the primary myotome (a sheet of mononucleated fibers). This primary myotome is immediately expanded as other cells that were initially not the most medial somitic cells differentiate into muscle fibers. In amniotes, myotome expansion is achieved by the immigration of myogenic cells from the dermomyotome lips into the myotome. The presence of a morphological dermomyotome expressing known myogenic genes in all vertebrates strongly argues that at least some cellular and molecular mechanisms of myotome expansion are also conserved. We suggest that in all vertebrates, myogenic precursors express pax3 and pax7 as external cells on the surface of the embryonic myotome, and down-regulate these genes as they begin to express MRF genes and move into the myotome.

The cellular embryology of the dermomyotome remains incompletely understood in any organism. In amniotes, dermomyotome origin is generally described as a default that occurs if sclerotome is not induced, but in aquatic vertebrates, where sclerotome develops late, this is not a viable mechanism and the primary choice appears to be dermomyotome versus myotome. In teleosts, it is not clear if the myogenic precursor cells that migrate from the somite to the fin buds are derived from the dermomyotome, as limb bud myogenic precursors are in amniotes (Neyt et al., 2000). Outstanding questions about the dermomyotome in amniotes may be profitably addressed in teleosts. Basic aspects of dermomyotomal cell lineage and cell movements are poorly understood. For example, it is unknown whether the dermomyotome derives from one type of epithelial somite cell or multiple types. Are there are any differences in cell fate between dorsal cells in the anterior of the somite and dorsal cells in the posterior of the somite? Are pax3 and pax7 expressed in the same dermomyotomal cells? If not, do these transcription factors identify distinct types of myogenic precursor cells? In addition, there is considerable controversy over whether cells from the dermomyotome lips all move directly into the myotome, or whether some first migrate to the rostral or caudal edge of the dermomyotome before entering the myotome (Ben-Yair et al., 2003; Denetclaw and Ordahl, 2000). Finally, there is controversy over whether the earliest myotome develops from cells that were never part of the dermomyotome (Gros et al., 2004; Kahane et al., 2001). The small and rapidly developing dermomyotome of zebrafish makes these questions relatively simple to address. The same detailed lineage and time-lapse analyses that have been so fruitful in understanding segmentation and early embryonic myotome specification should be informative for understanding dermomyotome cell lineage and cell behavior. Zebrafish genetic and cell biological approaches provide a new means of unraveling the molecular basis for the initial specification of dermomyotome and its subsequent differentiation into muscle fibers.

The dermomyotome and dermis formation

Within the amniotes, the dorsal dermis is derived from the dermomyotome (Scaal and Christ, 2004). In both birds (chick) and mammals (mouse) dermal progenitors have been shown to de-epithelialize from the dermomyotome regions including the dorsomedial lip. Moreover, single cells in dermomyotome can contribute to both dermis and later myotomal myogenesis in chick (Ben-Yair and Kalcheim, 2005). These progenitors first merge into the subectodermal mesenchyme before becoming part of distinct areas of the dermis (Olivera-Martinez et al., 2004; Scaal and Christ, 2004). As mentioned above, collagen is expressed in cells on the external surface of the teleost myotome, underlying the epidermis (Le Guellec et al., 2004; Rescan et al., 2005; Sire and Akimenko, 2004). Cell lineage labeling can directly test whether these cells are derived from the dermomyotome.

The dermomyotome and vascular formation

The dermomyotome contributes to blood vessels in amniotes. In the avian somite, angioblasts from the dermomyotome migrate into the dorsal dermis and also to the ventrolateral body wall and the limbs (He et al., 2003; Wilting et al., 1995). Clonal analysis in the chick has shown that angioblasts and myoblasts originate, at least in part, from the same precursor cells in the dermomyotome (Kardon et al., 2002). Somitic cells in zebrafish can be converted to a vascular fate by over-expression of a single gene, scl (Gering et al., 2003). Whether external cells in teleosts generate vascular endothelial cells during normal development can be readily determined by the types of cell lineage experiments discussed above.

Evolutionary considerations

The dermomyotome is a transient structure in all species, of variable thickness, becoming apparent shortly after somite formation, and disappearing during the early growth period. The thickness of the dermomyotome does not correlate with evolutionary relationships between species, nor does it correlate with ultimate body size or morphology of the adult. Further characterization of the early development of external cells and their subsequent differentiation may indicate whether the variation in thickness simply reflects differences in the relative developmental stage at which we and others have looked for the dermomyotome and/or has functional implications.

There are several possible reasons for dermomyotome conservation. First, other cells of the embryo may depend on the epithelial cell layer for their normal development. These may include neural crest or the primordium of the lateral line, both of which likely migrate on the external surface of the somite in all vertebrates. Second, an epithelial external layer may provide a mechanical constraining force for the embryo prior to the development of more mature connective tissue and epidermis. This mechanical role may be required to shape the myotome. Third, some aspect of myogenic cell differentiation or morphogenesis may require cell-cell interactions that are only possible in an epithelium. Finally, the epithelium may provide a simple and adaptable mechanism for sequestering stem cells capable of contributing to later muscle growth. One or more of these factors may be a developmental constraint that has maintained an epithelial external cell layer in all vertebrates.

No sign of the dermomyotome has been reported in cephalochordates, raising the question of whether its first appearance coincides with the vertebrate radiation. If the dermomyotome is an ancient and conserved structure that evolved in the last common ancestor of all extant vertebrates, it may have a similar level of significance for developmental evolution as, for example, that already attributed to the neural crest (though clearly in different ways). Although the importance of the dermomyotome has long been accepted in the amniotes, the idea is new for other vertebrates including teleosts.

Acknowledgements

Embryos were generously provided by Hans Hoffman (Bauer Labs, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.), David Bodznick (Wesleyan University), Vernon Scholey (Comision Interamericana del Atun Tropical, Bellavista, Panama), Hans Bergler (Teichwirtschaftlicher Beispielsbetrieb Woellershof, Stoernstein, Germany), Hans-Peter Gollmann, BAW Scharfling, Mondsee, Austria). We thank Ann Burke for helpful discussions, and Xuesong Feng for contributions to Fig. 3. This work was supported by a Donaghue Investigator Award and NIH R01 HD37509 (SHD, MJFB, SEP, EA), by Austrian Science Foundation (FWF) grants P16425 and P14193 (WS, PS, JRH), and the MRC (SMH and CLH).

References

- Armand O, Boutineau AM, Mauger A, Pautou MP, Kieny M. Origin of satellite cells in avian skeletal muscles. Arch Anat Microsc Morphol Exp. 1983;72:163–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yair R, Kahane N, Kalcheim C. Coherent development of dermomyotome and dermis from the entire mediolateral extent of the dorsal somite. Development. 2003;130:4325–4336. doi: 10.1242/dev.00667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yair R, Kalcheim C. Lineage analysis of the avian dermomyotome sheet reveals the existence of single cells with both dermal and muscle progenitor fates. Development. 2005;132:689–701. doi: 10.1242/dev.01617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagden CS, Currie PD, Ingham PW, Hughes SM. Notochord induction of zebrafish slow muscle mediated by Sonic hedgehog. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2163–2175. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.17.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone Q. Locomotor muscle. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, editors. Fish Physiology. Academic Press; New York: 1978. pp. 361–424. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M, Bajard L, Chang T, Daubas P, Hadchouel J, Meilhac S, Montarras D, Rocancourt D, Relaix F. The formation of skeletal muscle: from somite to limb. J Anat. 2003;202:59–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutelle O, Blagden CS, Hampson R, Halai C, Rigby PW, Hughes SM. Hedgehog signalling is required for maintenance of myf5 and myoD expression and timely terminal differentiation in zebrafish adaxial myogenesis. Dev Biol. 2001;236:136–150. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Pai V, Dal Pai-Silva M, Carvalho ED, Fujihara CY, Gregorio EA, Curi PR. Morphological, histochemical and morphometric study of the myotomal muscle tissue of the pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus Holmberg 1887): Serrasalminae, Characidae, Teleostei. Anat Histol Embryol. 2000;29:283–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0264.2000.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Pai-Silva M, Freitas EMS, Dal Pai V, Rodrigues AD. Morphological and histochemical study of the myotomal muscle in pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus Holmberg, 1887) during the initial growth phases. Arch Fish Mar Res. 2003;50:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Denetclaw WF, Ordahl CP. The growth of the dermomyotome and formation of early myotome lineages in thoracolumbar somites of chicken embryos. Development. 2000;127:893–905. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto SH, Melançon E, Eisen JS, Westerfield M. Identification of separate slow and fast muscle precursor cells in vivo, prior to somite formation. Development. 1996;122:3371–3380. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood PR, Gulyaev D, Kryvi H. Origin and differentiation of muscle fibre types in the trunk of the sturgeon, Acipenser stellatus Pallas. Sarsia. 1987;72:343–344. [Google Scholar]

- Flood PR, Kryvi H. The origin and differentiation of red and white muscle fibres in the sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus) J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1982;3:125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong RF, Holland PWH. Bayesian phylogenetic analysis supports monophyly of ambulacraria and of cyclostomes. Zool Sci. 2002;19:593–599. doi: 10.2108/zsj.19.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gering M, Yamada Y, Rabbitts TH, Patient RK. Lmo2 and Scl/Tal1 convert non-axial mesoderm into haemangioblasts which differentiate into endothelial cells in the absence of Gata1. Development. 2003;130:6187–6199. doi: 10.1242/dev.00875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi A, Tettamanti G, Martin BL, Gaffield W, Pownall ME, Hughes SM. Hedgehog regulation of superficial slow muscle fibres in Xenopus and the evolution of tetrapod trunk myogenesis. Development. 2004;131:3249–3262. doi: 10.1242/dev.01194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros J, Scaal M, Marcelle C. A two-step mechanism for myotome formation in chick. Dev Cell. 2004;6:875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves JA, Hammond CL, Hughes SM. Fgf8 drives myogenic progression of a novel lateral fast muscle fibre population in zebrafish. Development. 2005;132 doi: 10.1242/dev.01958. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadchouel J, Carvajal JJ, Daubas P, Bajard L, Chang T, Rocancourt D, Cox D, Summerbell D, Tajbakhsh S, Rigby PW, Buckingham M. Analysis of a key regulatory region upstream of the Myf5 gene reveals multiple phases of myogenesis, orchestrated at each site by a combination of elements dispersed throughout the locus. Development. 2003;130:3415–3426. doi: 10.1242/dev.00552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton L. The formation of somites in Xenopus. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1969;22:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Papoutsi M, Huang R, Tomarev SI, Christ B, Kurz H, Wilting J. Three different fates of cells migrating from somites into the limb bud. Anat Embryol. 2003;207:29–34. doi: 10.1007/s00429-003-0327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE. The Diversity of Fishes. Blackwell Sciences; Malden: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Henry CA, Amacher SL. Zebrafish slow muscle cell migration induces a wave of fast muscle morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;7:917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollway GE, Currie PD. Myotome meanderings. Cellular morphogenesis and the making of muscle. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:855–860. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Christ B. Origin of the epaxial and hypaxial myotome in avian embryos. Anat Embryol. 2000;202:369–374. doi: 10.1007/s004290000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery WR, Swalla BJ. Tunicates. In: Gilbert SF, Raunio AM, editors. Embryology, constructing the organism. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland: 1997. pp. 331–364. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston IA. Temperature influences muscle differentiation and the relative timing of organogenesis in herring (Clupea harengus) larvae. Mar Biol. 1993;116:363–379. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner S. Mit besonderer Beruecksichtigung der Selachier. Archiv fuer Anatomie und Entwickelungsgeschichte; 1892. Ueber die allgemeine Entwicklung der Rumpf- und Schwanzmusculatur bei Wirbelthieren; pp. 153–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kahane N, Cinnamon Y, Bachelet I, Kalcheim C. The third wave of myotome colonization by mitotically competent progenitors: regulating the balance between differentiation and proliferation during muscle development. Development. 2001;128:2187–2198. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalcheim C, Cinnamon Y, Kahane N. Myotome formation: a multistage process. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:161–173. doi: 10.1007/s004410051277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G, Campbell JK, Tabin CJ. Local extrinsic signals determine muscle and endothelial cell fate and patterning in the vertebrate limb. Dev Cell. 2002;3:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AM, Rubinstein NA. Why are fetal muscles slow? Nature. 1980;288:266–269. doi: 10.1038/288266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobiyama A, Nihei Y, Hirayama Y, Kikuchi K, Suetake H, Johnston IA, Watabe S. Molecular cloning and developmental expression patterns of the myoD and MEF2 families of muscle transcription factors in the carp. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:2801–2813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacalli TC, Kelly SJ. Somatic motoneurones in amphioxus larvae: cell types, cell position and innervation patterns. Acta Zool. 1999;80:113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Le Guellec D, Morvan-Dubois G, Sire JY. Skin development in bony fish with particular emphasis on collagen deposition in the dermis of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:217–231. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15272388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie FR. The development of the chick. Henry Holt and Company; New York: 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Albors O, Gil F, Ramirez-Zarzosa G, Vazquez JM, Latorre R, Garcia-Alcazar A, Arencibia A, Moreno F. Muscle development in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata, L.) and sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax, L.): Further histochemical and ultrastructural aspects. Anat Histol Embryol. 1998;27:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1998.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer F. Die Elemente der Rumpfmuskulatur bei Cyclostomen und Hoeheren Wirbelthieren. Ein Beitrag zur Phylogenie der quergestreiften Muskelfaser. Morphol Jahrb. 1894;21:473–619. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer F. Die Entwicklung des Muskelsystems und der electrischen Organe. In: Hertwig O, editor. Handbuch der Vergleichenden und Experimentellen Entwicklungslehre der Wirbeltiere. Gustav Fischer Verlag; Jena: 1906. pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao T. Electron-microscopic studies on myotomes of larval lamprey, Lampetra japonica. Anat Rec. 1977;187:383–403. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091870309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyt C, Jagla K, Thisse C, Thisse B, Haines L, Currie PD. Evolutionary origins of vertebrate appendicular muscle. Nature. 2000;408:82–86. doi: 10.1038/35040549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nornes S, Mikkola I, Krauss S, Delghandi M, Perander M, Johansen T. Zebrafish Pax9 encodes two proteins with distinct C-terminal transactivating domains of different potency negatively regulated by adjacent N-terminal sequences. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26914–26923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera-Martinez I, Thelu J, Dhouailly D. Molecular mechanisms controlling dorsal dermis generation from the somitic dermomyotome. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:93–101. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15272374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oustanina S, Hause G, Braun T. Pax7 directs postnatal renewal and propagation of myogenic satellite cells but not their specification. EMBO J. 2004;23:3430–3439. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patruno M, Radaelli G, Mascarello F, Candia Carnevali MD. Muscle growth in response to changing demands of functions in the teleost Sparus aurata (L.) during development from hatching to juvenile. Anat Embryol. 1998;198:487–504. doi: 10.1007/s004290050199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson KJ, Cameron RA, Davidson EH. Set-aside cells in maximal indirect development: Evolutionary and developmental significance. Bioessays. 1997;19:623–631. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pownall ME, Gustafsson MK, Emerson CP., Jr. Myogenic regulatory factors and the specification of muscle progenitors in vertebrate embryos. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:747–783. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Zarzosa G, Gil F, Latorre R, Ortega A, Garcia-Alcaraz A, Abellan E, Vazquez JM, Lopez-Albors O, Arencibia A, Moreno F. The larval development of lateral musculature in gilthead sea bream Sparus aurata and sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;280:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rescan PY. Regulation and functions of myogenic regulatory factors in lower vertebrates. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 2001;130:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescan PY, Collet B, Ralliere C, Cauty C, Delalande JM, Goldspink G, Fauconneau B. Red and white muscle development in the trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) as shown by in situ hybridisation of fast and slow myosin heavy chain transcripts. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:2097–2101. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.12.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescan PY, Ralliere C, Chauvigne F, Cauty C. Expression patterns of collagen I (alpha1) encoding gene and muscle-specific genes reveal that the lateral domain of the fish somite forms a connective tissue surrounding the myotome. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:605–611. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlerson A, Veggetti A. Cellular echanisms of ost-embryonic muscle growth in aquaculture species. In: Johnston IA, editor. Muscle development and growth. Academic Press; San Diego: 2001. pp. 103–140. [Google Scholar]

- Scaal M, Christ B. Formation and differentiation of the avian dermomyotome. Anat Embryol. 2004;208:411–424. doi: 10.1007/s00429-004-0417-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvarzstein M, Kirn A, Haffter P, Cordes SP. Expression of Zkrml2, a homologue of the Krml1/val segmentation gene, during embryonic patterning of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) Mech Dev. 1999;80:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P, Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Mansouri A, Gruss P, Rudnicki MA. Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells. Cell. 2000;102:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HC, Saetre BO, Havik B, Ellingsen S, Fjose A. The zebrafish Pax3 and Pax7 homologues are highly conserved, encode multiple isoforms and show dynamic segment-like expression in the developing brain. Mech Dev. 1998;70:49–63. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu DG, Luo HL, Morris SC, Zhang XL, Hu SX, Chen L, Han J, Zhu M, Li Y, Chen LZ. Lower Cambrian vertebrates from south China. Nature. 1999;402:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sire JY, Akimenko MA. Scale development in fish: a review, with description of sonic hedgehog (shh) expression in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:233–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporle R. Epaxial-adaxial-hypaxial regionalisation of the vertebrate somite: evidence for a somitic organiser and a mirror-image duplication. Dev Genes Evol. 2001;211:198–217. doi: 10.1007/s004270100139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiassny MLJ, Wiley EO, Johnson GD, de Carvalho MR. Gnathostome Fishes. In: Donaghue MJ, Cracraft J, editors. Assembling the Tree of Life. OUP; NY: 2004. pp. 410–429. [Google Scholar]

- Stickney HL, Barresi MJ, Devoto SH. Somite development in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:287–303. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1065>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber W, Haslett JR, Goldschmid A, Sanger AM. Patterns of superficial fibre formation in the European pearlfish (Rutilus frisii meidingeri) provide a general template for slow muscle development in teleost fish. Anat Embryol. 1998;197:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s004290050159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunier ALJ. Les premiers stades de la differentiation interne du myotome et la formation des elements sclerotomatiques chez les acraniens, les Selaciens, et les Teleosteens. Tijdschrifts Nederlandsche Dierkunkige Vereniging. 1911;12:75–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S. Stem cells to tissue: molecular, cellular and anatomical heterogeneity in skeletal muscle. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:413–422. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezaki N, Figueroa F, Zaleska-Rutczynska Z, Takahata N, Klein J. The phylogenetic relationship of tetrapod, coelacanth, and lungfish revealed by the sequences of forty-four nuclear genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1512–1524. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veggetti A, Mascarello F, Scapolo PA, Rowlerson A. Hyperplastic and hypertrophic growth of lateral muscle in Dicentrarchus labrax (L.). An ultrastructural and morphometric study. Anat Embryol. 1990;182:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00187522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialleton L. Le devellopement des muscles rouges. Comptes Rendus de L’Association des Anatomistes. 1902;1902:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman RE. Development of the lateral musculature in the teleost, Brachydanio rerio: a fine structural study. Am J Anat. 1969;125:457–493. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001250406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg ES, Allende ML, Kelly CS, Abdelhamid A, Andermann P, Doerre G, Grunwald DJ, Riggleman B. Developmental regulation of zebrafish MyoD in wild-type, no tail, and spadetail embryos. Development. 1996;122:271–280. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilting J, Brand-Saberi B, Huang R, Zhi Q, Kontges G, Ordahl CP, Christ B. Angiogenic potential of the avian somite. Dev Dyn. 1995;202:165–171. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]