Abstract

A healthy lifestyle may ameliorate metabolic syndrome (MetS); however, it remains unclear if incorporating nuts or seeds into lifestyle counseling (LC) has additional benefit. A 3-arm, randomized, controlled trial was conducted among 283 participants screened for MetS using the updated National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for Asian Americans. Participants were assigned to a LC on the AHA guidelines, LC + flaxseed (30 g/d) (LCF), or LC + walnuts (30 g/d) (LCW) group. After the 12-wk intervention, the prevalence of MetS decreased significantly in all groups: −16.9% (LC), −20.2% (LCF), and −16.0% (LCW). The reversion rate of MetS, i.e. those no longer meeting the MetS criteria at 12 wk, was not significantly different among groups (LC group, 21.1%; LCF group, 26.6%; and LCW group, 25.5%). However, the reversion rate of central obesity was higher in the LCF (19.2%; P = 0.008) and LCW (16.0%; P = 0.04) groups than in the LC group (6.3%). Most of the metabolic variables (weight, waist circumference, serum glucose, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein (Apo) B, ApoE, and blood pressure) were significantly reduced from baseline in all 3 groups. However, the severity of MetS, presented as the mean count of MetS components, was significantly reduced in the LCW group compared with the LC group among participants with confirmed MetS at baseline (P = 0.045). Our results suggest that a low-intensity lifestyle education program is effective in MetS management. Flaxseed and walnut supplementation may ameliorate central obesity. Further studies with larger sample sizes and of longer duration are needed to examine the role of these foods in the prevention and management of MetS.

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS),12 a constellation of metabolic abnormalities including central obesity, dyslipidemia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia, is a well-established risk factor for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1). Owing to rapid transitions toward high energy intake and sedentary lifestyle in last few decades, MetS has become a major health challenge in China and affects ∼15.1% (71 million people) of Chinese adults according to the updated National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) criteria for Asian Americans (2). Thus, it is critical to establish strategies to prevent or control the epidemic trend of MetS and its consequences.

Compelling evidence supports the role of diet in the development of MetS (3). The scientific advisory committee of the AHA has published dietary recommendations for MetS management (4). A decreased prevalence of MetS was reported with intensive approaches (5), i.e. very low-energy diets (6) and structured dietary regimens, including low-fat and high-carbohydrate diets (7), and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension eating program (8). However, it is unknown whether a less intensive lifestyle program might also be effective.

Flaxseed is a complex food containing high amounts of PUFA, mainly α-linolenic acid (ALA), an (n-3) fatty acid, as well as soluble fiber, lignan precursors, and other substances that may have health benefits (9). Similarly, walnuts are also a rich source of PUFA [both (n-3) and (n-6) fatty acids] and contain several nonfat constituents, such as plant protein (particularly arginine-rich proteins) and fiber. Recently, 2 meta-analyses found that flaxseed and walnut interventions improved lipid profiles and reduced CVD risk (10, 11). However, the effects of these foods on MetS remain unclear.

Therefore, we conducted a 3-arm, randomized, controlled clinical trial to investigate the effects of flaxseed and walnut supplementation as an adjunct intervention to healthy lifestyle counseling (LC) on the management of MetS in Chinese men and women. In addition, we also evaluated the effects of all 3 interventions on MetS components, especially central obesity, which is particularly important for Chinese, who are known to have higher amounts of abdominal adiposity with a given BMI, i.e. a metabolically obese phenotype as compared with Europeans (12).

Methods

Study design and participants.

The present study was a randomized controlled trial. Participant screening was performed at 2 large universities in Shanghai by reviewing clinical records of annual physical examinations conducted in 2008. MetS was defined by the updated NCEP ATP III criteria for Asian Americans. LDL cholesterol ≥ 3.4mmol/L was also added as an additional inclusion criteria to reflect borderline high LDL cholesterol level (13). Therefore, individuals were included if they met at least 3 of the following criteria: 1) waist circumference ≥ 90 cm for men or ≥ 80 cm for women (defined as central obesity); 2) triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L; 3) HDL cholesterol < 1.03 mmol/L for men or < 1.30 mmol/L for women; 4) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mm Hg 5) fasting glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L; and 6) LDL cholesterol ≥ 3.4 mmol/L. Exclusion criteria were: 1) history of allergy or high consumption of nuts, flaxseed, or sesame seeds (>120 g/wk); 2) clinically diagnosed renal, liver, heart, pituitary, thyroid, or mental diseases, or alimentary tract ulceration or diseases affecting absorption; 3) history of CVD, cancer(s), or mental disorders; 4) current or previous (in the preceding 6 mo) use of antidepressants, estrogen, or steroid therapy; and 5) pregnancy or lactation.

A total of 5845 university faculty and staff members were screened for eligibility and 331 individuals responded to our recruitment solicitations and were then invited to attend a screening visit, during which time eligibility was verified (see CONSORT diagram, Supplemental Fig. 1). A total of 283 participants (158 men and 125 women) were recruited. Based on the screening data, 239 patients had MetS and 44 had 2 components of MetS plus elevated LDL cholesterol. Participants were block randomized to 1 of the 3 intervention arms: 1) LC; 2) LC with 30 g/d of flaxseed supplementation (LCF); or 3) LC with 30 g/d of walnuts (LCW) supplementation. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute for Nutritional Sciences and all participants provided written informed consent.

Intervention.

All participants received counseling and written materials based on the AHA guidelines, including a low-fat diet; limited consumption of red or processed meat; decreasing salt intake to <5 g/d; increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, and fish; smoking cessation; and, if they consumed alcohol, moderate consumption of wine was encouraged (4). At the beginning of the intervention, participants engaged in a 1-h group session with a registered dietitian and were provided with guidance on maintaining their usual levels of energy intake and physical activity.

Two isocaloric breads were provided for each participant every day. The breads were similar except that 30 g of flaxseed or walnuts were incorporated into the 100-g-weight bread for the LCF or LCW groups, respectively. The 2 breads provided 1600–2100 kJ/d energy. All breads were prepared in a single bakery under the supervision of 2 registered dietitians. Quality control was conducted by random sampling and weighing the breads weekly. Participants were instructed to substitute the breads for part of the staple food such as rice and other wheat products in their diet. It should be noted that the flaxseed and walnut breads could be differentiated by their appearance and taste; therefore, the participants were not necessarily unaware of the intervention arms. However, researchers, dietitians, laboratory technicians, and statisticians were unaware of the group assignment.

Adherence to study protocol was ensured by asking participants to return any unused bread that was then weighed. Compliance was calculated as the weight of breads consumed divided by the prescribed weight of total breads throughout the intervention. In addition, the ALA content of erythrocyte membranes was used as a marker of adherence to flaxseed and walnut breads.

Measurements.

At baseline, we administered a short-form FFQ, a 3-d food record, and a 32-item general questionnaire about education, physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire, short 7-d format), lifestyle, health status, history of disease, and medication use. Standardized protocols were used to collect anthropometric measures. Body weight and height were measured in light indoor clothing without shoes to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. BMI was calculated as kg/m2. Waist circumference was obtained at the mid-point between the lowest rib and the iliac crest to the nearest 0.1 cm, after inhalation and exhalation and using nonstretch tape measures. Blood pressure was measured on the right arm using an electronic blood pressure monitor (Omron HEM- 705CP, OMRON Healthcare) with participants in a comfortable seated position after at least a 5-min rest. Participants were required to fast overnight and blood samples were collected. Serum samples were stored at −80°C until laboratory analyses. All examinations and sample collections were repeated at the completion of the 12-wk intervention.

Serum glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and apolipoprotein (Apo) A-1, B, and E were measured enzymatically on an automatic analyzer (Hitachi 7080) with reagents purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries. Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) was quantified from resolved erythrocyte with automated immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics). Serum insulin levels were determined by a sandwich ELISA (Linco Research). ALA levels in erythrocyte membranes were measured by GC (14).

Statistical methods.

The analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle. We used descriptive statistics with means and SD to characterize the study participants. ANOVA and χ2 tests were used to compare means of quantitative variables and qualitative traits, respectively. Natural-logarithmic transformation was applied prior to analyses if values had a skewed distribution (triglycerides and ApoE). Within- and between-group differences were expressed as means (95% CI) or medians [interquartile range (IQR)]. Within-group and between-group differences were compared using paired Student’s t tests and ANOVA, respectively. At 12 wk, we calculated the proportion of participants who no longer met the criteria for MetS (i.e. reverted MetS). The severity of MetS was presented by the mean number (count) of MetS components. Subgroup analyses stratified by sex, baseline central obesity status, baseline BMI, and weight change were also performed. Differences in the reversion of MetS and its components were assessed by using logistic regression analysis with the LC group set as the referent. Data were analyzed using Stata (version 9.2) and P < 0.05 (2-sided) was considered significant. Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust for multiple testing due to a large number of outcome variables.

Results

A total of 277 (97.9%) of the 283 participants randomized completed the 12-wk intervention. Participants dropped out due to intervention-unrelated health conditions, business issues, and loss of interest (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics.

The age range was 25–65 y and 55.8% (n = 158) of the participants were men. After randomization, the 3 groups appeared fairly balanced with respect to major demographic characteristics, medication uses, and metabolic profiles. Based on the baseline survey, 179 participants (63.3%) met the MetS criteria and 256 (90.5%) had at least 2 components of MetS (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the randomized participants at baseline1

| Intervention groups |

||||

| Variable | LC, n = 95 | LCF, n = 94 | LCW, n = 94 | P-value4 |

| Age, y | 48.6 ± 8.0 | 48.5 ± 8.0 | 48.2 ± 8.4 | 0.95 |

| Men, n (%) | 52 (54.7) | 53 (56.4) | 53 (56.4) | 0.97 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 21 (22.1) | 27 (28.7) | 26 (27.7) | 0.54 |

| Alcohol drinkers, n (%) | 51 (53.7) | 61 (64.9) | 54 (57.4) | 0.47 |

| Medication, n (%) | ||||

| Antihypertensive agents | 32 (33.7) | 34 (36.2) | 39 (31.7) | 0.45 |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 6 (6.3) | 4 (4.3) | 5 (5.3) | 0.81 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 2 (2.1) | 3 (3.2) | 4 (4.3) | 0.69 |

| Aspirin and antiphlogiston agents | 9 (9.5) | 6 (6.4) | 12 (12.8) | 0.36 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.4 ± 2.4 | 25.1 ± 2.3 | 25.7 ± 2.9 | 0.22 |

| MetS (NCEP ATP III),2n (%) | 64 (67.4) | 57 (60.6) | 58 (61.7) | 0.59 |

| MetS components, n (%) | ||||

| Central obesity2 | 66 (69.5) | 70 (74.5) | 73 (77.7) | 0.44 |

| Elevated fasting glucose2 | 64 (67.4) | 58 (61.7) | 55 (58.5) | 0.45 |

| Elevated triglycerides2 | 59 (62.1) | 60 (63.8) | 57 (60.6) | 0.90 |

| Reduced HDL cholesterol2 | 36 (37.9) | 22 (23.4) | 28 (29.8) | 0.10 |

| Elevated blood pressure2 | 61 (64.2) | 54 (57.5) | 60 (63.8) | 0.56 |

| Metabolic profile | ||||

| Weight, kg | 70.6 ± 10.9 | 69.7 ± 9.4 | 72.2 ± 11.4 | 0.28 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 89.7 ± 7.6 | 88.7 ± 6.2 | 90.0 ± 7.8 | 0.42 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 133.7 ± 14.6 | 133.0 ± 17.1 | 135.0 ± 16.2 | 0.69 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 85.4 ± 9.0 | 85.6 ± 11.6 | 86.5 ± 9.9 | 0.75 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 6.1 ± 1.3 | 0.49 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 0.76 |

| Triglycerides3, mmol/L | 1.94 (1.45–2.80) | 1.89 (1.36–2.77) | 1.99 (1.44–2.66) | 0.53 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 0.26 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 4.2 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 0.47 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.56 |

| ApoA1, g/L | 1.54 ± 0.38 | 1.53 ± 0.35 | 1.47 ± 0.31 | 0.28 |

| ApoB, g/L | 1.15 ± 0.32 | 1.10 ± 0.30 | 1.08 ± 0.27 | 0.24 |

| ApoE3, g/L | 0.59 (0.50–0.75) | 0.56 (0.16–0.68) | 0.54 (0.45–0.67) | 0.15 |

| Insulin, pmol/L | 52.4 ± 34.1 | 47.1 ± 28.0 | 47.5 ± 24.4 | 0.38 |

Data are mean ± SD or (%) unless otherwise indicated.

(%) of the participants who met the specific criteria.

3Data are medians (IQR) and were log-transformed for across group comparisons.

-value for comparison across groups.

Dietary intake and physical activity levels.

Based on the weight ratio of consumed and prescribed breads, dietary adherence was deemed excellent, with a mean adherence of 98.7%. At 12 wk, total energy intakes decreased from baseline and in all groups (all P < 0.02 for within-group differences). The percent of energy from protein increased in all groups (all P < 0.002 for within-group differences). The percent of energy from dietary fat increased, whereas that from carbohydrate decreased in the LCF and LCW groups (all P < 0.006 for within-group differences). The consumption of PUFA was higher in the LCF and LCW groups (all P < 0.001 for between-group differences) than in the LC group. Compared with the LC group, the LCF and LCW groups consumed more dietary fiber and had greater ALA levels in their erythrocyte membranes (P < 0.001 for both between-group differences) (Table 2). Physical activity did not change in any of the groups or differ from the LC group in the LCF or LCW group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Dietary intake and physical activity level of the participants during the 12-wk intervention period1

| Variable | LC, n = 95 | LCF, n = 94 | LCW, n = 94 |

| Total energy intake, kJ/d | |||

| Baseline | 10,341 ± 268 | 9915 ± 259 | 9873 ± 238 |

| 12 wk | 8665 ± 276a | 8740 ± 263b | 9058 ± 247b |

| Energy from carbohydrates, % | |||

| Baseline | 51.3 ± 0.7 | 51.5 ± 0.8 | 51.7 ± 0.7 |

| 12 wk | 49.9 ± 0.7 | 46.6 ± 0.8a, d | 48.1 ± 0.7a |

| Energy from protein, % | |||

| Baseline | 14.3 ± 0.2 | 14.3 ± 0.2 | 13.8 ± 0.2 |

| 12 wk | 15.3 ± 0.2b | 15.7 ± 0.2a | 15.1 ± 0.2a |

| Energy from fat, % | |||

| Baseline | 33.7 ± 0.7 | 34.4 ± 0.7 | 34.0 ± 0.6 |

| 12 wk | 34.3 ± 0.7 | 37.5 ± 0.8b,c | 36.5 ± 0.7b,d |

| SFA, g/d | |||

| Baseline | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 0.5 |

| 12 wk | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 10.8 ± 0.5 | 11.5 ± 0.5d |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids, g/d | |||

| Baseline | 13.4 ± 0.7 | 14.2 ± 0.6 | 14.3 ± 0.6 |

| 12 wk | 17.9 ± 0.7a | 17.9 ± 0.7a | 17.5 ± 0.6a |

| PUFA, g/d | |||

| Baseline | 25.3 ± 0.9 | 26.6 ± 1.1 | 24.9 ± 1.1 |

| 12 wk | 17.9 ± 0.9a | 32.3 ± 1.6a,c | 33.6 ± 1.2a,c |

| Dietary fiber, g/1000 kJ | |||

| Baseline | 22.6 ± 0.8 | 20.5 ± 1.3 | 20.5 ± 1.3 |

| 12 wk | 16.7 ± 0.8a | 42.2 ± 1.3a,c | 33.9 ± 1.3a,c |

| Physical activity,2MET-min/d | |||

| Baseline | 313 ± 27 | 329 ± 25 | 373 ± 27 |

| 12 wk | 347 ± 28 | 339 ± 26 | 390 ± 27 |

| Erythrocyte membrane ALA, % of total fatty acids | |||

| Baseline | 0.24 ± 0.10 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 0.22 ± 0.10 |

| 12 wk | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.27 ± 0.11 |

| Change from baseline to 12 wk | −0.02 ± 0.12 | 0.16 ± 0.17a,c | 0.04 ± 0.10a,c |

Data are mean ± SD. Letters indicate different from baseline (a < 0.001; b P < 0.05) or from LC (c P < 0.001; d P < 0.05).

MET-min, minutes at a given metabolic equivalent level.

Changes in MetS status.

The percentage of all participants with MetS was ∼46% at completion of the study, which was lower than that at baseline (P < 0.05). The percentage of individuals with MetS decreased from baseline by 16.9, 20.2, and 16.0% in the LC, LCF, and LCW groups, respectively. The percentage of participants with each MetS component also decreased significantly from baseline. In addition, the reversion rate of central obesity was higher in the LCF (19.2%; P = 0.008) and LCW (16.0%; P = 0.04) groups than in the LC group (6.3%) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of MetS and its components among study participants1

| LC, n = 95 | LCF, n = 94 | LCW, n = 94 | |

| MetS and its components | |||

| MetS (NCEP ATP III) | |||

| Baseline | 64 (67.4) | 57 (60.6) | 58 (61.7) |

| 12 wk | 48 (50.5) | 38 (40.4) | 43 (45.7) |

| Reversion rate2 | 20 (21.1) | 25 (26.6) | 24 (25.5) |

| Central obesity | |||

| Baseline | 66 (69.5) | 70 (74.5) | 73 (77.7) |

| 12 wk | 62 (65.3) | 54 (57.5) | 61 (64.9) |

| Reversion rate2 | 6 (6.3) | 18 (19.2)a | 15 (16.0)a |

| Elevated fasting glucose | |||

| Baseline | 64 (67.4) | 58 (61.7) | 55 (58.5) |

| 12 wk | 50 (52.6) | 38 (40.4) | 38 (40.4) |

| Reversion rate2 | 20 (21.1) | 28 (29.8) | 22 (23.4) |

| Elevated triglycerides | |||

| Baseline | 59 (62.1) | 60 (63.8) | 57 (60.6) |

| 12 wk | 57 (60.0) | 54 (57.5) | 47 (50.0) |

| Reversion rate2 | 10 (10.5) | 15 (16.0) | 17 (18.1) |

| Reduced HDL cholesterol | |||

| Baseline | 36 (37.9) | 22 (23.4) | 28 (29.8) |

| 12 wk | 37 (39.0) | 31 (33.0) | 36 (38.3) |

| Reversion rate2 | 14 (14.7) | 7 (7.5) | 8 (8.5) |

| Elevated blood pressure | |||

| Baseline | 61 (64.2) | 54 (57.5) | 60 (63.8) |

| 12 wk | 40 (42.1) | 42 (44.7) | 48 (51.0) |

| Reversion rate2 | 24 (25.3) | 14 (14.9) | 21 (22.3) |

Data are (%). a Different from the LC group, P < 0.05.

Reversion rate indicated the proportion of participants who met the criterion at baseline but not at 12 wk.

We observed no between-group differences in outcomes for any subgroup analyses defined by sex, baseline central obesity status, baseline BMI, or weight change, except that among participants with central obesity at baseline, reversion of hyperglycemia was notable in the LCF group, with an odds ratio (95% CI) of 3.01 (1.10–7.54) for LCF compared with the LC group after multivariate adjustment (Supplemental Fig. 2).

In addition, the severity of MetS, presented as the mean count of MetS components, was lower in the LCW group compared with the LC group (P = 0.045) among participants with confirmed MetS at baseline, although the 2 groups did not differ after Bonferroni’s correction (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Differences in anthropometrics and serum biochemistry between the LCF or LCW group and the LC group and changes within groups during the 12-wk intervention period1

| Within-group differences |

Between-group differences |

||||

| LC, n = 95 | LCF, n = 94 | LCW, n = 94 | LCF vs. LC | LCW vs. LC | |

| Weight, kg | −0.82 (−1.11 to −0.52)a | −1.18 (−1.51 to −0.86)a | −0.92 (−1.19 to −0.65)a | −0.37 (−0.81 to 0.07) | −0.10 (−0.50 to 0.30) |

| Waist circumference, cm | −1.23 (−1.82 to −0.63)a | −1.50 (−2.09 to −0.91)a | −1.16 (−1.72 to −0.61)a | −0.27 (−1.11 to 0.56) | 0.06 (−0.75 to 0.87) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | −7.0 (−9.5 to −4.5)a | −8.8 (−11.0 to −6.6)a | −8.2 (−10.7 to −5.8)a | −1.77 (−5.10 to 1.55) | −1.22 (−4.71 to 2.27) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | −4.4 (−5.8 to −3.1)a | −5.0 (−6.3 to −3.7)a | −4.2 (−5.7 to −2.7)a | −0.57 (−2.46 to 1.31) | −0.23 (−1.79 to 2.25) |

| HbA1c, % | 0.06 (−0.11 to 0.21) | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.04) | 0.05 (−0.02 to 0.12) | −0.07 (−0.16 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.10 to 0.09) |

| Glucose, mmol/L | −0.44 (−0.67 to −0.21)a | −0.57 (−0.77 to −0.37)a | −0.40 (−0.61 to −0.20)a | −0.13 (−0.44 to 0.17) | 0.03 (−0.27 to 0.34) |

| Triglycerides,2mmol/L | −0.04 (−0.50 to 0.33) | −0.07 (−0.50 to 0.32) | −0.07 (−0.52 to 0.36) | −0.02 (−0.30 to 0.25) | −0.02 (−0.27 to 0.24) |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | −0.47 (−0.73 to −0.20)a | −0.56 (−0.82 to −0.29)a | −0.35 (−0.59 to −0.10)a | −0.09 (−0.46 to 0.28) | 0.12 (−0.23 to 0.48) |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | −0.37 (−0.59 to −0.15)a | −0.44 (−0.67 to −0.21)a | −0.27 (−0.47 to −0.08)a | −0.07 (−0.39 to 0.24) | 0.10 (−0.19 to 0.38) |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | −0.12 (−0.19 to −0.05)a | −0.15 (−0.20 to −0.09)a | −0.09 (−0.15 to −0.03)a | −0.03 (−0.11 to 0.06) | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.12) |

| ApoA1, g/L | −0.09 (−0.15 to −0.03) a | −0.13 (−0.18 to −0.07) a | −0.07 (−0.13 to −0.01) a | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.05) | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.11) |

| ApoB, g/L | −0.07 (−0.11 to −0.02) a | −0.09 (−0.14 to −0.04) a | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.02) a | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.07) |

| ApoE,2g/L | −0.05 (−0.18 to 0.06) a | −0.05 (−0.17 to 0.05) a | −0.04 (−0.14 to 0.05) a | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.07) |

| Insulin, pmol/L | 4.14 (−8.52 to 16.9) | −0.48 (−6.54 to 5.58) | 3.66 (−1.32 to 8.70) | −4.68 (−18.7 to 9.36) | −0.48 (−13.1 to 14.1) |

| MetS counts,3n | −0.58 (−0.79 to −0.37)a | −0.81 (−1.08 to −0.53)a | −0.93 (−1.21 to −0.65)a | −0.23 (−0.57 to 0.11) | −0.35 (−0.69 to −0.01)b |

Data are means (95% CI) unless otherwise indicated. a Different from baseline, < 0.05; b Different from the LC group, P < 0.05.

Data are medians (IQR) and were log-transformed for across group comparisons.

Data from participants with MetS at baseline were analyzed [ = 64 (LC), n = 57 (LCF), and n = 58 (LCW)].

Effects on MetS traits.

Body weight decreased significantly in all groups. Weight loss tended to be greater in the LCF group (P = 0.10) compared with the LC group. Most of the other CVD risk factors (waist circumference, serum glucose, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, ApoB, ApoE, and blood pressure) decreased significantly from baseline in all 3 groups (Table 4).

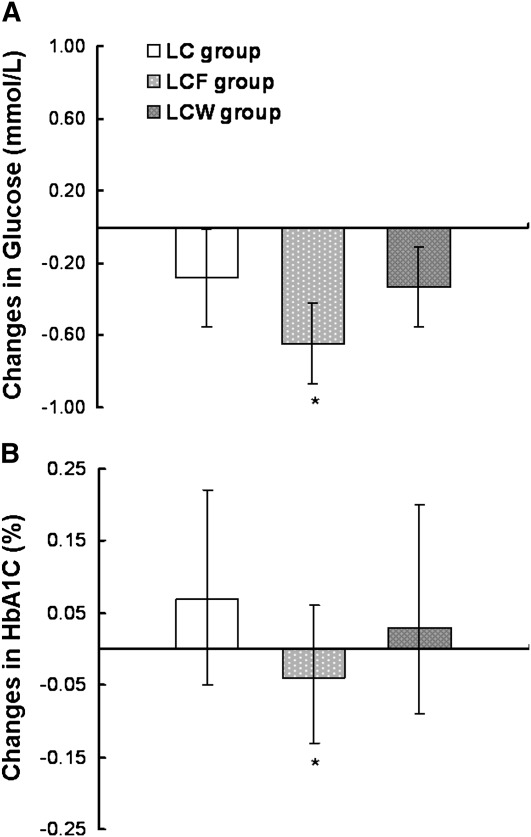

Because flaxseed supplementation has effects on central obesity and hyperglycemia, we further performed a post hoc analysis of between-group differences in diabetes-related traits among participants with central obesity at baseline (Fig. 1). Compared with the LC group, serum glucose was lower in the LCF group, with a between-group mean difference of −0.35 mmol/L (95% CI, −0.69 to −0.01; P = 0.047). Moreover, flaxseed supplementation also prevented an increase of HbA1c, with a between-group mean difference of −0.10 (95% CI, −0.20 to 0.00; P = 0.05). Among LC and LCF participants without central obesity at baseline, serum glucose also decreased during the study (P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Changes in the serum glucose concentration (A) and blood HbA1c (B) during the 12-wk intervention period in participants with central obesity at baseline. Values are means (95% CI), n = 66 (LC), n = 70 (LCF), and n = 73 (LCW). * Different from LC group, P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this 3-arm, randomized controlled dietary intervention, a less-intensive LC program was found to significantly decrease body weight and CVD risk factors among Chinese participants with clinically confirmed MetS or higher MetS risk. This also is one of the first studies to document the comparative effects of flaxseed and walnut supplementation in ameliorating central obesity as well as the severity of MetS in this high risk population.

Previous studies have demonstrated that lifestyle modification, especially combined with dietary change, plays an important role in controlling MetS (3, 5, 8, 15–17), although many of these interventions were far more intensive than the regimens pursued in the current study and promoted substantive weight loss or large shifts in dietary patterns. In this study, all participants were instructed to follow a general healthy lifestyle according to AHA guidelines. After the 12-wk intervention, a 16.7% reduction of MetS was observed, which suggests that a low-intensity LC program could be useful for MetS management.

Flaxseed and walnuts are considered energy-dense foods due to their high contents of PUFA. Interestingly, participants assigned to the 30 g/d flaxseed- or walnut-supplemented diets did not gain weight, and participants in the LCF group showed a tendency to lose more weight than those in the LC group. Moreover, our data showed that LC plus flaxseed or walnuts may have additional benefits on central adiposity compared with LC only. Abdominal obesity is well recognized as a potential etiologic factor of MetS (18); hence, reverted central obesity is important for overall MetS management. This finding from our study is particularly important for Asians, a population that is likely to have metabolic obesity (12), even under normal weight conditions, compared with Caucasians (19). However, the mechanisms by which flaxseed and walnuts act in reverting abdominal obesity remain unclear, although limited evidence suggests that the abundance of PUFA in the diet might serve as an important modulator for body fat deposition. In a small clinical trial, Summers et al. (20) reported that changing from a diet rich in SFA to one abundant in PUFA resulted in a 25% reduction of abdominal fat without altering body weight. A cross-sectional study also reported that a high dietary PUFA:SFA ratio was inversely associated with waist circumference and waist:hip ratio (21).

Another noteworthy finding is that among participants with central obesity at baseline, flaxseed incorporation seemed to decrease fasting glucose and prevent the increase of HbA1c. Few studies have evaluated the effect of flaxseed on glucose metabolism. Nonetheless, administering flaxseed lignan in rodents was shown to prevent and delay the development of diabetes (22). Our previous intervention trial also showed that flaxseed lignan improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetics patients (23). Thus, consistent with these results, this study provides evidence for the first time, to our knowledge, that flaxseed may have a favorable impact on glycemic control in individuals with MetS or at increased risk for MetS.

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial with a feeding component to evaluate the effects of lifestyle education with and without supplementation of whole flaxseed or walnuts among individuals with MetS. Our study, however, has certain limitations. First, due to discrepancies in screening between physicians and study staff, not all study participants met the criteria for MetS, although the vast majority (91%) had at least 2 components of MetS. Second, the relatively small sample size limited our power to detect differences in many metabolic endpoints, especially because our control group also lost weight. It should be noted that in previous studies, the control group received virtually no intervention and thus had a greater likelihood of detecting between-group differences (8, 24). Finally, the duration of this intervention, although fairly typical for diet interventions, may be too short to detect clinically meaningful changes in metabolic disorders.

In conclusion, our results suggest that a low-intensity LC program could be useful in MetS management. Although flaxseed or walnut supplementation did not provide additional benefits on blood lipids, incorporating these foods into diets may improve central obesity status. Further studies with larger sample sizes and of longer duration are needed to examine the role of these foods in the prevention and management of MetS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yiping Qiu and Zhiming Ye, Xichao Teng, Lili Chen, and Xiaoqiang Fei from Huadong Hospital, Shanghai University, and Donghua University for taking part in this study. We also thank Liang Sun, Chen Liu, Jing Wang, Wei Gan, Jingwen Zhu, Qianlu Jin, Shaojie Ma, and He Zheng in our research group for their kind assistance at various stages of this trial. H.W. conducted research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.P., Z.Y., Q.Q., H.L., and X.C. conducted research and analyzed data; W. D-W. edited the paper; L.L., G.Z., D.Y., G.Z., and Y.Z. conducted research and collected data; L.T. and Y.F. collected dietary intake data; H.Z. and X.C. recruited participants and conducted research; and F.B.H. and X.L. designed research and edited the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (The Knowledge Innovation Program, grant no. KSCX1-YW-02), the Chief Scientist Program of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SIBS2008006), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, grant no. 2011CB504002), and the California Walnut Commission (Sacramento, CA), who provided funding and donated walnuts. Pizzey's Milling (Glanbia plc., North America) donated the flaxseed.

This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT00733772 and NCT00742742.

Supplemental Figures 1 and 2 are available with the online posting of this paper at jn.nutrition.org.

Abbreviations used: ALA, α-linolenic acid; IQR, interquartile range; LC, lifestyle counseling; LCF, lifestyle counseling with 30 g/d of flaxseed supplementation; LCW, lifestyle counseling with 30 g/d of walnuts supplementation; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NCEP ATP III, National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III.

Literature Cited

- 1.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Executive summary. Cardiol Rev. 2005;13:322–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu D, Reynolds K, Wu X, Chen J, Duan X, Reynolds RF, Whelton PK, He J. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and overweight among adults in China. Lancet. 2005;365:1398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreassi MG. Metabolic syndrome, diabetes and atherosclerosis: influence of gene-environment interaction. Mutat Res. 2009;667:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, Appel LJ, Daniels SR, Deckelbaum RJ, Erdman JW, Jr, Kris-Etherton P, Goldberg IJ, et al. AHA Dietary Guidelines: revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:2284–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Goldberg R, Haffner S, Ratner R, Marcovina S, Fowler S. The effect of metformin and intensive lifestyle intervention on the metabolic syndrome: the Diabetes Prevention Program randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:611–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kukkonen-Harjula KT, Borg PT, Nenonen AM, Fogelholm MG. Effects of a weight maintenance program with or without exercise on the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial in obese men. Prev Med. 2005;41:784–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poppitt SD, Keogh GF, Prentice AM, Williams DEM, Sonnemans HMW, Valk EEJ, Robinson E, Wareham NJ. Long-term effects of ad libitum low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets on body weight and serum lipids in overweight subjects with metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi T, Azizi F. Beneficial effects of a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2823–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall Iii C, Tulbek MC, Xu Y, Steve LT. Flaxseed. Advances in food and nutrition research. Fargo: Academic Press; 2006. p. 1–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan A, Yu D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Franco OH, Lin X. Meta-analysis of the effects of flaxseed interventions on blood lipids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:288–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banel DK, Hu FB. Effects of walnut consumption on blood lipids and other cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:56–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lear SA, Humphries KH, Kohli S, Chockalingam A, Frohlich JJ, Birmingham CL. Visceral adipose tissue accumulation differs according to ethnic background: results of the Multicultural Community Health Assessment Trial (M-CHAT). Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:353–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bondia-Pons I, Castellote AI, López-Sabater MC. Comparison of conventional and fast gas chromatography in human plasma fatty acid determination. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;809:339–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu FB, Willett WC. Dietary patterns, insulin resistance, and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:910–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutsey PL, Steffen LM, Stevens J. Dietary intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2008;117:754–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esposito K, Marfella R, Ciotola M, Di Palo C, Giugliano F, Giugliano G, D'Armiento M, D'Andrea F, Giugliano D. Effect of a Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1440–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson LE, Graham TE. Metabolic syndrome, a cardiovascular disease risk factor: role of adipocytokines and impact of diet and physical activity. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29:808–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan JCN, Malik V, Jia W, Kadowaki T, Yajnik CS, Yoon K-H, Hu FB. Diabetes in Asia: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. JAMA. 2009;301:2129–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Summers LK, Fielding BA, Bradshaw HA, Ilic V, Beysen C, Clark ML, Moore NR, Frayn KN. Substituting dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat changes abdominal fat distribution and improves insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia. 2002;45:369–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh A. Comparison of anthropometric, metabolic and dietary fatty acids profiles in lean and obese dyslipidaemic Asian Indian male subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;61:412–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad K. Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside from flaxseed delays the development of type 2 diabetes in Zucker rat. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;138:32–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan A, Sun J, Chen Y, Ye X, Li H, Yu Z, Wang Y, Gu W, Zhang X, et al. Effects of a flaxseed-derived lignan supplement in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salas-Salvado J, Fernandez-Ballart J, Ros E, Martinez-Gonzalez M-A, Fito M, Estruch R, Corella D, Fiol M, Gomez-Gracia E, et al. Effect of a Mediterranean diet supplemented with nuts on metabolic syndrome status: one-year results of the PREDIMED randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2449–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]