Abstract

Introduction

The current medical literature has conflicting results about factors related to hypothyroidism and nodular recurrences during follow-up of hemithyroidectomized patients. We aimed to evaluate factors that may have a role in new nodule formation, hypothyroidism, increase in thyroid lobe and increase in nodule volumes in these patients with and without Hashimoto's thyroiditis (HT), and with and without levothyroxine (LT4) use.

Material and methods

We enrolled 140 patients from five different hospitals in Ankara and evaluated their thyroid tests, autoantibody titre results and ultrasonographic findings longitudinally between two visits with a minimum 6-month interval.

Results

In patients with HT there was no significant difference between the two visits but in patients without HT, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels and nodule volume were higher, and free T4 levels were lower in the second visit. Similarly, in patients with LT4 treatment there was no difference in TSH, free T4 levels, or lobe or nodule size between the two visits, but the patients without LT4 had free T4 levels lower in the second visit. Regression analysis revealed a relationship between first visit TSH levels and hypothyroidism during follow-up.

Conclusions

Patients who have undergone hemithyroidectomy without LT4 treatment and without HT diagnosis should be followed up more carefully for thyroid tests, new nodule formation and increase in nodule size. The TSH levels at the beginning of the follow-up may be helpful to estimate hypothyroidism in hemithyroidectomized patients.

Keywords: hemithyroidectomy, hypothyroidism, nodular goitre, Hashimoto's disease, thyroid lobectomy

Introduction

Thyroid nodules are one of the most frequent endocrinological problems in the adult population [1, 2]. The use of fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) gives clues prior to surgical intervention about pathology of the nodule [3], and improved ultrasonographic techniques provide better evaluation of the whole thyroid parenchyma. Therefore, surgical interventions aimed at saving the nodule-free part of the thyroid parenchyma are increasingly employed, to avoid postoperative hypothyroidism and complications of bilateral surgical techniques [4, 5].

Thyroid lobectomy or hemithyroidectomy has advantages over total thyroidectomy [4–6] for solitary nodules but it comes with the risk of nodule recurrence [4–6]. Nodule recurrence may be problematic during follow-up, particularly in patients who are found to have carcinoma at postoperative pathological evaluation [4–6]. Higher risk of nodule recurrence or risk of hypothyroidism after hemithyroidectomy, increase in remaining thyroid lobe volume and/or nodule volume and benefits of levothyroxine (LT4) use in these patients remain unclear [6–11]. Meanwhile, the role of iodine deficiency or the effects of successful iodization (as in Turkey) on nodule recurrence after hemithyroidectomy still remain unknown [12, 13]. Iodine intake may have effects in Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT) [14]. It is also not clear whether presence of HT may have an impact on nodular recurrence in these patients.

In the present study we sought the risk factors that may be associated with nodular recurrence, hypothyroidism, increase in thyroid lobe or nodule volume in patients with or without HT, and in patients on and not on LT4 use, by evaluation of longitudinal data of patients who had undergone hemithyroidectomy.

Material and methods

We enrolled 140 patients (27 men, 113 women) within ages 18-80 years from five different hospitals in Ankara. We included patients who had undergone hemithyroidectomy and had records of two different visits which were separated by at least 6 months duration. Patients with a history of multiple thyroid operations, radioactive iodine treatment, patients who were receiving drugs for other ailments that may affect thyroid functions (such as amiodarone or steroids), hypophyseal pathologies, patients with renal impairments and patients who had changes in the drug regimen between the 2 visits were excluded. Second visit measurements were accepted if they were a minimum of 3 months after the surgery, to exclude effects of postoperative oedema and thyroid function variations. The interval between the two visits was 30.6 ±9.7 months. All patients were informed about the study and all provided written informed consent before their evaluation. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Ufuk University as the main centre and carried out following the principles of the Helsinki Conference.

We collected data on the pre- and postoperative diagnosis at the first visit, on thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4 and free T3), serum thyroid autoantibodies, LT4 use, remaining lobe volume, and nodule volumes on ultrasonography at both visits, and assessed for the presence and/or appearance of new nodules on the second visit. Nodules were defined as > 3 mm diameter on ultrasonography in all three dimensions and ultrasonographic thyroid evaluation was made by the same endocrinologists educated by the same thyroid centre. Increase in nodule volume was defined as > 20% increase in at least two dimensions of the nodule and increase in lobe volume was defined as > 10% increase in lobe volume across the study interval [15, 16]. Hypothyroidism was defined as serum TSH ≥ 5 mIU/ ml, including subclinical hypothyroidism.

For diagnosis of HT, we accepted pathological examination of operated thyroid lobe parenchyma.

Hormonal measurements and thyroid autoantibodies

Thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4, free T3) were measured by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) Immulite 2000 (Diagnostic Products Corp, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and Abbot Architect 2000 in four hospitals and by the same method, and by Elecsys 170® in one hospital. Measured TSH levels were recorded as mIU/ml and free T4 and free T3 as pmol/l to have the same SI (Système International d'Unités) units. Thyroid autoantibodies were measured by the competitive radioimmunoassay (RIA) method (using Brahms® Dynotest) in one hospital, by the ECLIA method using Roche Elecsys 2010 in another hospital, and by the ECLIA method using Abbott Architect 2000 in three other hospitals. Interchangeability of Roche Elecsys 2010 and Abbot Architect 2000 measurements was tested before starting the study.

Ultrasonographic evaluation

Three university hospitals used General Electric® Logiq 5000 and a 9 mHz linear probe, and two hospitals used Esaote Colour Doppler US (MAG Technology Co, Ltd. Model: 796FDII Yung-ho City, Taipei; Taiwan) ultrasonography and a 9 mHz linear probe and General Electric Logiq 400 and an 11 mHz linear probe. Three dimensions of the thyroid gland were recorded and thyroid and nodule volumes were calculated by the formula “length X height X depth X pi/6” as ml [17]. Ultrasonographic evaluations were performed by endocrinologists who had ultrasonography education from the same centre (Ankara University, Endocrinology and Metabolic Diseases Department).

Statistical analysis

Differences in the test results between the two visits were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test by presence of HT, by gender, and by LT4 use. Factors found in bivariate analyses to be associated with hypothyroidism (increase in nodule number and volume, increase in thyroid volume) were evaluated by multivariate logistic regression analysis, using the program SPSS 16.0. Two-sided statistical significance was considered if the p value was < 0.05. For evaluation of increase in nodule size we compared the size of each nodule (there were 4 nodules maximum) between the two visits.

Results

Among 140 patients 27 (19.3%) were male, 113 (80.7%) were female, and mean age (± SD) was 52.7 (±11.9) years. Postoperative pathological examination revealed HT in 40 patients (28.6%). Incidence of HT (p = 0.018) and the anti-TPO antibody levels (p = 0.004 at first visit and p = 0.035 at second visit) were higher in women (Table I).

Table I.

Comparison of thyroid tests and ultrasonographic findings in men and women for two different visits

| Parameter | Female (mean ± SD) | Male (mean ± SD) | All patients (mean ± SD) | Difference (value of p)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 51.5 ±11.36 | 57.2 ±13.4 | 52.6 ±11.96 | 0.712 |

| Hashimoto thyroiditis [%] | 32.7 | 11.1 | 28.6 | 0.018* |

| LT4 use [%] | 83.8 | 16.2 | 48.6 | 0.245 |

| 1st visit TSH [mIU/ml] | 3.2 ±3.19 | 1.42 ±1.16 | 2.85 ±2.62 | 0.063 |

| 1st visit sT3 [pmol/l] | 3.67 ±1.04 | 4.33 ±1.35 | 3.80 ±1.13 | 0.172 |

| 1st visit sT4 [pmol/l] | 16.03 ±3.72 | 16.74 ±4.15 | 16.17 ±3.81 | 0.623 |

| 1st visit anti-TG | 69.18 ±63.31 | 20.88 ±16.04 | 60.25 ±53.44 | 0.246 |

| 1st visit anti-TPO | 56.30 ±42.5 | 11.97 ±8.50 | 47.06 ±28.05 | 0.004* |

| 2nd visit TSH | 4.29 ±3.45 | 2.15 ±1.95 | 3.88 ±2.92 | 0.583 |

| 2nd visit sT3 | 3.71 ±1.49 | 3.73 ±0.94 | 3.71 ±1.39 | 0.587 |

| 2nd visit T4 | 14.62 ±4.34 | 14.92 ±3.41 | 14.68 ±4.17 | 0.697 |

| 2nd visit anti-TG | 78.30 ±76.12 | 21.46 ±19.70 | 68.13 ±64.01 | 0.865 |

| 2nd visit anti-TPO | 63.74 ±60.21 | 13.17 ±14.10 | 53.85 ±45.03 | 0.035* |

| 1st visit nodule no. | 0.89 ±0.79 | 1.00 ±0.97 | 0.91 ±0.89 | 0.685 |

| 2nd visit nodule no. | 1.15 ±1.18 | 1.00 ±1.33 | 1.12 ±1.20 | 0.784 |

| 1st visit remaining lobe volume [ml] | 9.8 ±8.2 | 12.0 ±9.11 | 10.2 ±8.4 | 0.816 |

| 2nd visit remaining lobe volume [ml] | 9.2 ±9.1 | 11.95 ±8.22 | 9.78 ±9.07 | 0.017* |

SD – standard deviation

statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Thyroid tests and ultrasonography in HT and non-HT groups

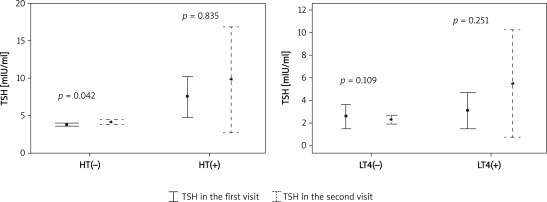

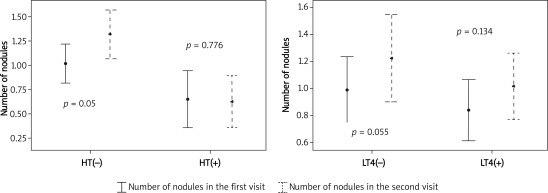

Comparison of thyroid tests and ultrasonographic evaluation between the two visits in HT and non-HT patients are summarized in Table II. There were no differences between the two visits among patients with HT, whereas in patients without HT, TSH was higher at the second visit (p = 0.042), free T4 was lower (p = 0.001), number of nodules was higher (p = 0.005) and nodule sizes were increased with a slight statistically significant difference (p = 0.043) (Figures 1 and 2). However, when we compared the two visits using the clinical significance definitions (i.e. > 20% increase in nodule volume and > 10% increase in remaining lobe volume) those differences were not significant (for nodule size p = 0.523 and for lobe size p = 0.329).

Table II.

Comparison of thyroid tests and ultrasonographic findings in HT and non-HT patients for two successive visits

| Parameter | Hashimoto (+) | Hashimoto (–) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st visit | 2nd visit | Value of p | 1st visit | 2nd visit | Value of p* | |

| TSH [mIU/ml] | 5.93 ±5.81 | 8.58 ±7.57 | 0.835 | 1.72 ±1.07 | 2.00 ±1.47 | 0.042* |

| sT4 [pmol/l] | 15.66 ±4.01 | 14.73 ±5.34 | 0.122 | 16.38 ±3.72 | 14.65 ±3.61 | 0.001* |

| sT3 [pmol/l] | 3.85 ±1.22 | 3.94 ±2.11 | 0.641 | 3.78 ±1.10 | 3.62 ±0.93 | 0.394 |

| Anti-TG | 159.53 ±151.17 | 214.95 ±207.29 | 0.491 | 13.67 ±6.61 | 15.7 ±7.97 | 0.412 |

| Anti-TPO | 125.14 ±112.17 | 174.53 ±157.54 | 0.761 | 12.26 ±7.52 | 13.62 ±11.07 | 0.736 |

| Remaining lobe volume** | 9.15 ±7.94 | 8.78 ±7.94 | 0.554 | 10.69 ±8.62 | 10.17 ±7.71 | 0.811 |

| Number of nodules | 0.65 ±0.83 | 0.65 ±0.92 | 0.776 | 1.02 ±1.01 | 1.3 ±1.27 | 0.005* |

| Nodule 1 volume | 9.8 ±2.7 | 10.5 ±2.6 | 0.494 | 9.0 ±3.7 | 9.6 ±3.8 | 0.135 |

| Nodule 2 volume | 3.7 ±2.2 | 4.2 ±2.8 | 0.515 | 2.0 ±1.5 | 2.2 ±1.8 | 0.209 |

| Nodule 3 volume | 2.9 ±1.2 | 2.8 ±2.0 | 0.109 | 3.7 ±1.7 | 3.9 ±1.4 | 0.136 |

| Nodule 4 volume** | 2.1 ±1.0 | 2.0 ±1.0 | 0.981 | 2.03 ±2.0 | 2.52 ±1.9 | 0.043* |

p < 0.05

Nodule volumes are calculated in millilitres (ml)

Figure 1.

Comparison between two visits regarding TSH levels, in HT vs. non-HT, on LT4 vs. not on LT4 groups

Figure 2.

Comparison between two visits regarding number of nodules, in HT vs. non-HT, on LT4 vs. not on LT4 groups

Among these patients with HT 11 (27.5%) were having LT4 treatment, and among the patients without HT, 39 (39%) were taking LT4.

Thyroid tests and ultrasonography in patients with and without LT4 use

Ultrasonography findings and thyroid tests of patients were compared separately between the two visits by LT4 use (Table III). There was no significant difference between the two visits in patients on LT4 treatment, but in patients not on LT4, free T4 was significantly lower at the second visit (p = 0.001) and nodule size had increased in one nodule slightly (p = 0.043). There was an increase in nodule number but statistical tests did not reveal significance (p = 0.055). For clinical significance the two groups were compared (by χ2 test) and neither nodule size (p = 0.588) nor remaining lobe volume (p = 0.513) was statistically or clinically different.

Table III.

Comparison of thyroid tests and ultrasonographic findings in patients on and not on LT4 use, for two different visits

| Parameter | Patients on LT4 | Patients not on LT4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st visit | 2nd visit | Value of p | 1st visit | 2nd visit | Value of p* | |

| TSH [mIU/ml] | 3.11 ±2.86 | 5.55 ±4.84 | 0.251 | 2.61 ±4.46 | 2.31 ±1.67 | 0.109 |

| sT4 [pmol/l] | 17.07 ±4.45 | 16.51 ±4.87 | 0.053 | 15.31 ±2.84 | 13.81 ±3.10 | 0.001* |

| sT3 [pmol/l] | 3.76 ±1.31 | 3.44 ±3.11 | 0.069 | 3.84 ±0.95 | 4.03 ±1.75 | 0.572 |

| Remaining lobe volume** | 9.96 ±9.75 | 9.83 ±9.18 | 0.274 | 10.53 ±7.03 | 9.72 ±6.55 | 0.329 |

| Number of nodules | 0.83 ±0.94 | 1.01 ±1.01 | 0.134 | 0.98 ±1.05 | 1.22 ±1.36 | 0.055 |

| Nodule 1 volume** | 12.8 ±4.7 | 13.2 ±4.8 | 0.274 | 5.8 ±1.4 | 6.2 ±1.6 | 0.288 |

| Nodule 2 volume | 8.9 ±2.4 | 9.4 ±3.5 | 0.195 | 2.1 ±1.1 | 2.0 ±1.4 | 0.446 |

| Nodule 3 volume | 2.8 ±1.4 | 2.9 ±2.5 | 0.799 | 1.4 ±1.2 | 1.4 ±1.6 | 0.347 |

| Nodule volume** | 1.3 ±1.0 | 1.3 ±1.1 | 0.891 | 2.2 ±2.3 | 3.1 ±1.1 | 0.043* |

p < 0.05

Nodule volumes are calculated in millilitres (ml)

Factors related to hypothyroidism, number of nodules, increase in nodule and remaining lobe volumes

We evaluated the role of age, gender, presence of HT, LT4 use and TSH value at the first visit on hypothyroidism at the second visit. Only the TSH value at the first visit was associated with hypothyroidism (p = 0.035, exp(B) = 1.083, 95% CI: 1.006-1.167). The same parameters were also tested for increase in number of nodules, for nodule size and for remaining lobe volume (by logistic regression analysis) and none of them were significantly related (p > 0.05).

Discussion

Partial thyroidectomies provide some advantages to the patient, for example they are associated with lower incidence of hypothyroidism and lower risks of surgical complications. Risk of chronic hypothyroidism was found to be 87% in subtotal and 46% in hemithyroidectomies compared to 100% in total thyroidectomies [4]. Hemithyroidectomy also lessens the risk of hypocalcaemia and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, but with a risk of nodule recurrence [5, 6]. The medical literature provides conflicting findings with regard to the factors associated with hypothyroidism and formation of new nodules, and the need for LT4 use to prevent recurrences. In the study by Niepomniszcze et al., 47 women with hemithyroidectomy due to follicular adenoma were evaluated with palpation for 7 years and they found 32% new nodule and goitre formation in patients without LT4 use [7]. In another study by Bellantone et al. evaluating patients with unilateral toxic nodular goitre, LT4 use decreased the recurrence of nodules [8], whereas Waldström et al. did not find any benefit of LT4 use in multinodular goitre patients after hemithyroidectomy [9]. In our study we did not find a relationship between number of nodules, nodule volume, lobe volume and LT4 use or HT. But when we compared patients on LT4 treatment with those not on LT4, patients not on LT4 treatment had lower free T4 and it resulted in a statistically significant (but not clinically important) increase in nodule volume at the second visit. Thus, we suggest that patients, particularly those not on LT4 treatment, should be followed closely for nodule enlargement and new nodule formation.

Wolmard et al. suggested the importance of starting TSH levels (> 1.6 µU/ml) and lymphocytic infiltration in thyroid parenchyma to predict risk of hypothyroidism in these patients [18]. Like Wormald et al., in our study, baseline TSH levels were significantly associated with hypothyroidism. However, in our study, patients with HT did not have a significant increase in TSH and number of nodules in the follow-up visit, while among those without HT patients had a significant increase in TSH and number of nodules. It is known that patients with nodular goitres may be predisposed to clonal or polyclonal nodular recurrence tendency [19] but in HT, lymphocytic infiltration and atrophy of the gland [20] may be the reason for the lower number of nodules.

There is also a debate on LT4 use for the prevention of nodule formation in the remaining thyroid lobe after a partial thyroidectomy. Alba et al. followed 223 patients and they found less nodular recurrence among patients with LT4 use [21]. Yetkin et al. reported that the nodular recurrence was associated with multinodularity, specific histopathological characteristics of the nodule and larger preoperative volume of the thyroid [10]. In our study although we found that patients not on LT4 treatment had a larger nodule volume and non-HT patients had an increased number of nodules, regression analysis did not reveal any significant relationship between presence of HT, LT4 use and nodule number or volume of lobes or nodules.

Our study is the first clinical study to evaluate nodules and volumes of the remaining lobes among HT and non-HT patients in an iodine deficient area. Studies in similar geographic areas are scarce and have different methodological criteria and/or surgical approaches [8–10]. Limitations of our study include the possibility of omitting the TSH fluctuations between the two visits due to possible poor compliance of LT4 in patients with drug use, and underestimating the effect of TSH on thyroid and/or nodule volumes. Another limitation is the absence of knowledge on simultaneous urinary iodine levels of patients, because some patients have tests before and after iodization in Ankara. Strengths include the fact that the ultrasonographic evaluations were all made by endocrinology specialists to provide standardization. An important point is the absence of the definition of increased lobe volume in medical literature, although there are defined criteria about increase in nodule volume. For consistency, we accepted more than 10% increase in the remaining lobe volume as “increase” for lobe evaluation. Finally, we cannot extrapolate these results to other partial thyroidectomies, since we only included hemithyroidectomized patients. Similarly, since we excluded patients with a history of multiple thyroid surgical interventions, we cannot make inferences on pathologies of recurrent nodules following multiple surgical interventions.

Meanwhile, despite continuing discussions and studies about benefits of LT4 treatment on nodule and thyroid volume, the dosage should be titrated carefully, considering multiple organ systems [22] and special groups of patients such as pregnant women [23].

In conclusion, our study revealed that starting TSH levels at a given time may have some value for prediction of the risk of hypothyroidism in the future. Caution is however needed with patients not on LT4 treatment for thyroid test abnormalities and in patients without HT diagnosis for the potential of a modest increase in nodule volume and increase in TSH levels. There is a need for additional prospective studies with larger sample sizes and meta-analyses to further explore risk factors associated with hypothyroidism and recurrence after hemithyroidectomies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express special thanks to Dr. AslIhan Alhan from Ufuk University Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of Statistics, for her precious effort in statistical calculations of the data, and to Assoc. Prof. Mkaya Mwanburi from Tufts University, Boston for his help in editing the paper and his interest in the topic. Also we would like to thank Dr. Zafer ŞahlI and surgeons from Ufuk University General Surgery Department, and all medical staff of Endocrinology Departments from Ankara University Ibni Sina Hospital, Baskent University, Ankara Numune Hospital, Ataturk Hospital and Ufuk University.

References

- 1.Bruneton JN, Balu-Maestro C, Marcy PY, et al. Very high frequency (13MHz) ultrasonographic examination of the normal neck: detection of normal lymph nodes and thyroid nodules. J Ultrasound Med. 1994;13:87–90. doi: 10.7863/jum.1994.13.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mortensen JD, Woolner LB, Bnnett WA. Gross and macroscopic findings in clinically normal thyroid glands. J Endocrinol Metab. 1955;15:1270–80. doi: 10.1210/jcem-15-10-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gharib H. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules: advantages, limitations, and effect. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:44–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaiman M, Nagibin A, Hagag P, et al. Hypothyroidism following partial thyroidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchesi M, Biffoni M, Faloci C, et al. High rate of recurrence after lobectomy for solitary thyroid nodule. World J Surg. 2000;24:1295–302. doi: 10.1080/110241502320789078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farkas EA, King TA, Bolton JS, et al. A comparison of total thyroidectomy and lobectomy in the treatment of dominant thyroid nodules. Am Surg. 2002;68:678–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niepomniszcze H, Garcia A, Faure E, et al. Long term folow-up og contralateral lobe in patients hemithyroidectomized for solitary follicular adenoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:509–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Boscherini M, et al. Predictive factors for recurrence after thyroid lobectomy for unilateral non-toxic goiter in an endemic area: results of a multivariate analysis. Surgery. 2004;136:1247–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldström C, Zedenius J, Guinea A, et al. Multinodular goitre presenting as a clinical single nodule: how effective is hemithyroidectomy? Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:34–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yetkin G, Uludag M, Onceken O, et al. Does unilateral lobectomy suffice to manage unilateral toxic goiter? Endocr Pract. 2010;16:36–41. doi: 10.4158/EP09140.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaitan E, Nelson CN, Poole GV. Endemic goitre and endemic thyroid disorder. World J Surg. 1991;21:205–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01659054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erdoğan G, Erdogan MF, Emral R, et al. Iodine status and goiter prevalence in Turkey before mandatory iodization. J Endocrinol Invest. 2002;25:224–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03343994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erdoğan MF, Ağbaht K, Altunsu T, et al. Current iodine status in Turkey. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32:617–22. doi: 10.1007/BF03346519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roti E, Montermini M, Robuschi G. Prevalance of hypothyroidism and Hashimoto's thyroiditis in two elderly populations with different iodine intake. In: Pinchera A, Ingbar SH, McKenzie JM, editors. Thyroid autoimunity. New York PA: Plenium Press; 1987. pp. 545–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brader AE, Viikinoski VP, Nickels JI, et al. Importance of thyroid abnormalities detected at US screening: a 5 year follow-up. Radiology. 2000;215:801–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn07801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. American Thyroid Association Guidelines Taskforce 2006. Management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differenciated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2006;16:109–42. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baskin HJ. Anatomy and anomalies. In: Baskin HJ, Duick DS, Levine RA, editors. Thyroid ultrasound and ultrasound-guided FNA. 2nd ed. USA: Springer Science and Business Media; 2008. pp. 47–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wormald R, Sheahan P, Rowley S, et al. Hemithyroidectomy for benign thyroid disease: who needs follow-up for hypothyroidism? Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33:587–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrer P, Broecker M, Zint A, et al. Thyroid nodules in recurrent multinodular goitres are predominantly polyclonal. J Endocrinol Invest. 1998;21:380–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03350774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dayan CM, Daniels GH. Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:99–107. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alba M, Fintini D, Lovicu RM, et al. Levothyroxine therapy in preventing nodular recurrence after hemithyroidectomy: a retrospective study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32:330–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03345722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salama HM, El-Dayem SA, Yousef H, Fawzy A, Abou-Ismail L, El-Lebedy D. The effects of L-thyroxine replacement on bone minerals and body composition in hypothyroid children. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6:407–13. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.14264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Q, Yu B, Huang R, et al. Assessment of thyroid function during pregnancy: the advantage of self-sequential longitudinal reference intervals. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:679–84. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.24139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]