Abstract

Introduction

Standard procedures carried out at a stroke department in patients after a cerebral event may prove insufficient for monitoring hemodynamic indices. Impedance cardiography enables hemodynamic changes to be monitored non-invasively. The aim of the work was to describe hemodynamic parameters in patients with acute phase of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and to analyse the correlation between the type of hemodynamic response and long-term prognosis.

Material and methods

The 45 consecutive subjects with ischemic stroke and 16 with a hemorrhagic stroke were examined additionally with impedance cardiography during the first day of hospitalization. The heart contractility, pump performance, afterload and preload indices were recorded and calculated automatically and the data analyzed in terms of 6-month mortality.

Results

We found a significant association between the systemic vascular resistance index, Heather index, stroke index, heart rate, systolic and diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure and mortality in patients with ischemic stroke (p = 0.002, p = 0.008, p = 0.012, p = 0.005, p = 0.007, p = 0.009, p = 0.002 respectively). Logistic regression analysis identified the thoracic fluid content as the most significant variable correlating with the non-survival of the patients with ischemic stroke and in the whole group (ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke). The significant parameters were also mean arterial pressure and stroke index in ischemic stroke (the correct answer ratio was 86.67%) and heart rate in the whole group (the correct answer ratio was 80.33%). There were no significant associations in hemorrhagic stroke.

Conclusions

The hemodynamic parameters correlate with long term prognosis in patients with ischemic brain stroke.

Keywords: ischaemic stroke, hemorrhagic, hemodynamics, impedance cardiography

Introduction

Brain stroke is one of the most common causes of death and a major cause of disability worldwide [1]. Every year 610,000 individuals suffer an ischemic stroke and 185,000 a hemorrhagic stroke in the United States [2]. New parameters are under evaluation as screening tools to select subjects with an elevated event risk [3–5]. Standard procedures carried out at a stroke department in patients after a cerebral event may prove insufficient for monitoring hemodynamic indices. The significance of hemodynamic monitoring is indicated by the high prevalence of ECG changes in patients after brain stroke [6]. The problem of the hospital and late mortality rate with stroke patients has not been solved. Based on the previously conducted research, it was believed that modifications of blood pressure affect the mortality rate of stroke patients [7]. Unfortunately, in the recently published research SCAST (SCAST Trial), where candesartan was used, it was indeed possible to lower blood pressure, but neither fewer cases of complications nor a lower late mortality rate were noted [8]. It appears that using one method of blood pressure reduction in patients with higher blood pressure is responsible for this occurrence. The above problem may be perhaps explained by a full analysis of the hemodynamic changes occurring in the acute phase of stroke. It may be performed by use of impedance cardiography (ICG) – a non-invasive method applied for the evaluation of hemodynamic parameters [9]. Its use can be justified by the high degree of reproducibility and short learning curve.

We assumed that an examination of patients with ICG would enable hemodynamic changes to be monitored in the acute phase of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and thus facilitate the right choice of medicine.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the hemodynamic parameters in patients with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. The second aim was to identify the hemodynamic predictors of 6-month mortality.

Material and methods

A total of 61 consecutive patients with stroke (30 men, 31 women) admitted to the Department of Neurology of the Medical University of Gdansk were recruited between December 2009 and May 2010. After routine examination all the patients with symptoms of stroke underwent computed tomography (CT) of the head. Their condition was assessed on the basis of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. The patients were divided into two groups according to the diagnosis (45 subjects with ischemic stroke and 16 with hemorrhagic stroke). An ICG was performed on the first post-admission day. The eight standard spot electrodes, a cuff, manometer and pulse oximeter were used. The NiccomoTM – Non Invasive Continuous Cardiac Output Monitor by Medis, made in Germany, was applied. The heart contractility indices, the acceleration index (ACI) and Heather index (HI), heart rate (HR), stroke index (SI), thoracic fluid content (TFC) and blood pressure were measured and the cardiac index (CI), left ventricular capacity work index (LCWI) and systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI) were then calculated automatically. Blood pressure was evaluated five times during a 10-min recording. The patients were administered with statins, antiplatelet medication and antihypertensive agents. Additional therapy was monitored by general practitioners. All the patients were referred to the neurological outpatient clinic. All of them underwent a 6-month follow-up.

The inclusion criteria were: diagnosed brain stroke confirmed by the computed tomography (CT) and evaluation by the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

Exclusion criteria were: unconfirmed or equivocal diagnosis and transient ischemic attacks. The other exclusion criteria were the general contraindications against ICG examination: severe aortic regurgitation, intra-aortic balloon pump, severe hypertension, a very low or high growth, severe obesity or severe malnutrition (septic shock is not considered as a contraindication [10, 11]).

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical University of Gdansk.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was conducted with the Student t-test for independent samples or with the Mann-Whitney U test. The analyses were performed separately for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. The normality of distribution was confirmed with the Brown-Forsythe test. Additionally, logistic regression for the ischemic stroke, for the hemorrhagic stroke and for the whole group was performed. All statistical calculations were performed using the Statistica 9.0 PL software package. A significance level of p < 0.05 was assumed.

Results

The patients’ ages ranged from 24 to 87 years; the mean age was 68.8 in the cohort as a whole (72.6 ±14.58 years in women and 64.6 ±12.16 years in men). Baseline clinical profile of the study is shown in Table I. Comparison of hemodynamic parameters obtained at 6-month follow-up in 45 patients with ischemic stroke and 16 patients with hemorrhagic stroke is shown in Table II. Logistic regression analysis identified the HR and the TFC as the most significant variables correlating with the non-survival of the patients in the whole group (ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke); the odds ratio for HR was 1.08 (95% CI 1.02-1.13) and the odds ratio for TFC was 1.12 (95% CI 1.01-1.24). The correct answer ratio was 80.33%. The most significant parameters in the ischemic stroke group were as follows: the TFC with the odds ratio 1.26 (95% CI 1.03-1.54), the MAP with the odds ratio 1.11 (95% CI 1.01-1.22), and SI with the odds ratio 0.86 (95% CI 0.75-0.99). The correct answer ratio was 86.67%. Logistic regression analysis in the hemorrhagic stroke group was not significant due to the small size of the group.

Equation 1. Logistic regression equation for the general group (ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke). P indicates the risk of death within 6 months.

Table I.

Baseline clinical profile of the study population

| Ischemic stroke (n = 45) | Hemorrhagic stroke (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|

| National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) | 10.6 ±6.6 | 15.6 ±7.6 |

| Thrombolysis therapy [%] | 11.8 | 0.0 |

| Arterial hypertension [%] | 85.3 | 69.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus [%] | 35.3 | 46.2 |

| Coronary artery disease [%] | 26.5 | 23.1 |

| Hyperlipidemia [%] | 44.1 | 46.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation [%] | 44.1 | 15.4 |

| Smoking [%] | 32.4 | 53.8 |

Table II.

Comparison of hemodynamic parameters obtained at 6-month follow-up in 45 patients with ischemic stroke and 16 patients with hemorrhagic stroke

| ICG parameter | Ischemic stroke | Hemorrhagic stroke | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death within 6 months (n = 10) | 6 months survival (n = 35) | Significance level p | Death within 6 months (n = 8) | 6 months survival (n = 8) | Significance level p | |

| ACI [1/100/s2] | 69.6 ±33.4 | 72.8 ±28.6 | 0.257† | 96.2 ±43.1 | 85.7 ±49.9 | 0.564† |

| CI [l/min/m2] | 3.0 ±0.5 | 3.3 ±0.7 | 0.224† | 3.7 ±0.7 | 3.0 ±1.0 | 0.111Δ |

| HI [Ohm/s2] | 7.6 ±4.2 | 12.0 ±5.0 | 0.008† | 13.3 ±4.9 | 13.7 ±7.7 | 0.793† |

| HR [1/min] | 91.2 ±18.6 | 75.8 ±14.5 | 0.005† | 97.3 ±19.7 | 83.4 ±13.9 | 0.104† |

| LCWI [kg × m/m2] | 4.1 ±0.7 | 4.0 ±1.0 | 0.614† | 4.8 ±1.1 | 4.1 ±1.1 | 0.495† |

| SI [ml/m2] | 33.6 ±8.8 | 44.4 ±12.2 | 0.012Δ | 39.2 ±9.5 | 36.8 ±13.4 | 0.676Δ |

| SVRI [dynes × s × m2/cm5] | 2951.6 ±721.8 | 2315.4 ±496.6 | 0.002Δ | 2141.1 ±645.3 | 3083.7 ±1237.6 | 0.128† |

| TFC [1/kOhm] | 42.4 ±8.0 | 37.0 ±7.5 | 0.054Δ | 39.9 ±6.5 | 36.5 ±6.8 | 0.318† |

| BPdia [mm Hg] | 90.4 ±16.0 | 79.2 ±9.7 | 0.009Δ | 84.9 ±14.8 | 92.2 ±11.7 | 0.318† |

| BPsys [mm Hg] | 164.8 ±20.7 | 141.8 ±20.3 | 0.007† | 144.8 ±25.1 | 155.0 ±29.2 | 0.466Δ |

| MAP [mm Hg] | 108.1 ±12.8 | 95.1 ±10.5 | 0.002Δ | 99.9 ±16.6 | 107.6 ±14.3 | 0.713† |

Values (mean ± standard deviation)

Student t test

Mann-Whitney U test

ACI – acceleration index, HR – heart rate, SI – stroke index, CI – cardiac index, HI – Heather index, LCWI – left ventricular capacity work index, TFC – thoracic fluid content, BPsys – systolic blood pressure, BPdia – diastolic blood pressure, MAP – mean arterial pressure

Ischemic stroke

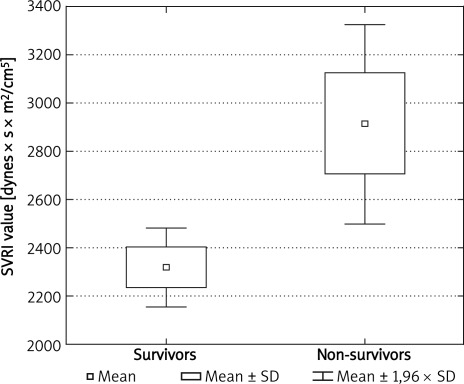

Patients with a low stroke index had a worse survival rate (p = 0.012). The HI, evaluating myocardial contractility, was lower in non-survivors (p = 0.008). An increased HR was a significant adverse prognostic factor (p = 0.005). Elevated systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure influenced long-term prognosis negatively. Individuals who survived 6 months after the stroke revealed a lower (p = 0.002) systemic vascular resistance index (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of SVRI in ischemic strokes in a 6-month follow-up).

Hemorrhagic stroke

In the group of patients suffering a hemorrhagic stroke, considerably fewer parameters acquired statistical significance (Table II). The SVRI index was the most remarkable. In contrast to the results for ischemic stroke, low values of this parameter were an adverse prognostic factor with p = 0.128. Because the group of patients was small, this tendency did not reach a significant level. The cardiac index, left cardiac work index and chest fluid did not reveal statistical significance. On the basis of blood pressure measurements, it was impossible to evaluate the long-term prognosis.

Discussion

The ICG is a useful tool for hemodynamic monitoring but in some clinical situations the data may be with bias [12]. This situations were mentioned before. Patients in very severe condition were not included to this study because of exlusion criteria. We present only a preliminary report because of the relatively small number of patients after brain stroke. The data were very impressive, so we decided to present them in this paper. The results show that the ICG data, together with the results of the physical examination and head CT, indicate a patient's prognosis. The most significant parameters influencing the 6-month prognosis of an ischemic stroke patient include the HI, HR, SVRI, SI, TFC and BP values. Better prognosis was obtained with a higher SVRI value. In contrast, a lower SVRI is probably useful as an indicator in patients with hemorrhagic stroke. Although the SVRI seems to be a significant predictor for the patients with stroke, it cannot be treated as an independent risk factor as it is a dependent parameter calculated on the basis of other parameters. The results of the logistic regression for ischemic stroke suggest that the survival of the patients after stroke is influenced by the preload and afterload of heart, described by the TFC and the MAP. The logistic regression for hemorrhagic stroke was not significant, but the character of the group was noticeable in the whole group analysis (the ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke together). In the best model the most important factors were the TFC and the HR. There were also ACI and CI present in the model, but they were not statistically significant. The differences between the model for ischemic stroke and the model for the whole group may suggest distinct factors corresponding with the death risk after ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. The evaluation of the importance of these findings needs further research. This report suggests that hemodynamic monitoring may support the diagnostic and therapeutic process in brain stroke patients.

In conclusion, the hemodynamic parameters correlate with long term prognosis in patients with ischemic brain stroke.

References

- 1.Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM. Stroke. Lancet. 2008;371:1612–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Vital statistics of the United States, data warehouse. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/MortFinal2003_WorkTable307.pdf. Accessed Spring/Summer 2008.

- 3.Lorenz MW, Schaefer C, Steinmetz H, Stizer M. Is carotid intima media thickness useful for individual prediction of cardiovascular risk? Ten-year results from the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS) Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2041–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen ZJ, Olsen TS, Andersen KK, Loft S, Ketzel M, Raaschou-Nielsen O. Association between short-term exposure to ultrafine particles and hospital admissions for stroke in Copenhagen, Denmark. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2034–40. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooney MT, Vartiainen E, Laatikainen T, Joulevi A, Dudi-na A, Graham I. Simplifying cardiovascular risk estimation using resting heart rate. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2141–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lleva P, Aronow WS, Amin H, Sandhu R, D'Aquila K. Prevalence of electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients with ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4:259–62. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandset EC, Murray G, Boysen G, et al. SCAST Study Group. Angiotensin receptor blockade in acute stroke. The Scandinavian Candesartan Acute Stroke Trial: rationale, methods and design of a multicentre, randomised- and placebo-controlled clinical trial ( NCT00120003) Int J Stroke. 2010;5:423–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hankey GJ. Lowering blood pressure in acute stroke: the SCAST trial. Lancet. 2011;377:696–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siebert J, Wtorek J, Rogowski J. Stroke volume variability – cardiovascular response to orthostatic maneuver in patients with coronary artery disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;873:182–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piechota M, Irzmański R, Banach M, Kowalski J, Pawlicki L. Impedance cardiography in haemodynamic monitoring of septic patients: a prospective study. Arch Med Sci. 2007;3:145–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piechota M, Irzmański R, Banach M, et al. Can impedance cardiography be routinely applied in patients with sepsis and severe sepsis? Arch Med Sci. 2006;2:114–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez MF, Tibayan RT, Marinas CE, Yamamoto ME, Caguioa EV. Prognostic value of hemodynamic findings from impedance cardiography in hypertensive stroke. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:65S–72S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]