Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor (EGIST) is a special type of gastrointestinal stromal tumor, which has similar biological characteristics to its counterpart, and occurs outside the gastrointestinal tract. It was identified first by Miettinen et al. [1], and named by Reith et al. [2]. The incidence of EGIST is extremely low, and so far there is no detailed epidemiological figure. To the best of our knowledge, EGIST has been commonly reported in the mesentery, omentum or retroperitoneum [1–4], and sporadically in the pleura [5], pancreas [6–12], liver [13–17], gallbladder [18], adrenal gland [19], bladder [20–22], prostate [23] and vagina [24, 25]. Most existing studies of EGIST are case reports, lacking enough information to clarify the disease; thus it is very difficult to establish helpful guidelines for clinicians. It is very common that EGIST is misdiagnosed for other tumors. Herein, we report an extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver, which was diagnosed by ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (US-FNAC), and review the literature, so as to help understand EGIST better.

A 53-year-old Chinese man was admitted to the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical College in July 2011 with the chief complaint of abdominal discomfort in the right upper quadrant for 1 month. The patient denied abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, hematochezia, fevers or chills. There was no loss of appetite or weight. He had an ultrasound scan three days previously in a local hospital, revealing a giant mass in the liver. He had had sub-total gastrectomy because of gastric ulcer in 2005.

Physical examination showed a well-developed man with abdominal distention; yellow pigmented lesions, hepatic palm and spider angioma were not seen; palpation indicated a large mass extending subcostally approximately 18 cm, moderately tender and non-pulsatile; percussion tenderness over hepatic region and shifting dullness were negative.

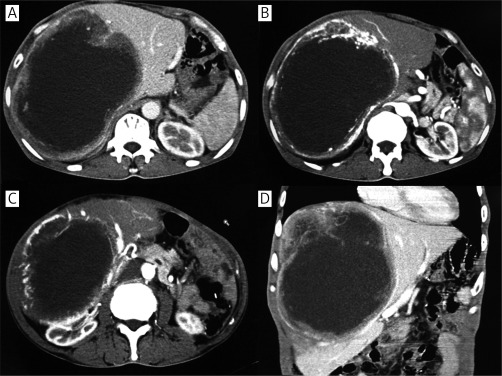

Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography of the upper abdomen was performed. It showed a giant irregular low-density mass almost occupying the full right lobe of the liver; it was encircled by rich blood vessels, and the maximum dimensions were about 17 cm × 20 cm; the pancreas and right kidney were dislocated (Figure 1). Chest X-ray showed no abnormal lesions. Tumor markers AFP, CA19-9 and CEA were all negative. Fecal occult blood test was also negative. Both glutamate alanine aminotransferase and glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase were in the normal range. HBsAg, HBeAb and HBcAb were positive in second liver two half-and-half tests.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography. Contrast-enhanced CT shows a large mass about 17 cm × 20 cm almost occupying the full right lobe of the liver, which was encircled by rich blood vessels. The pancreas and right kidney were dislocated (A, B, C – transverse scan; D – coronal scan)

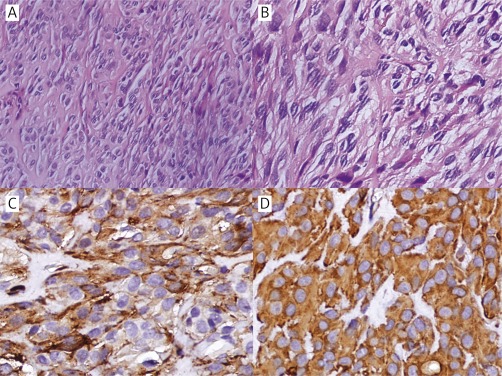

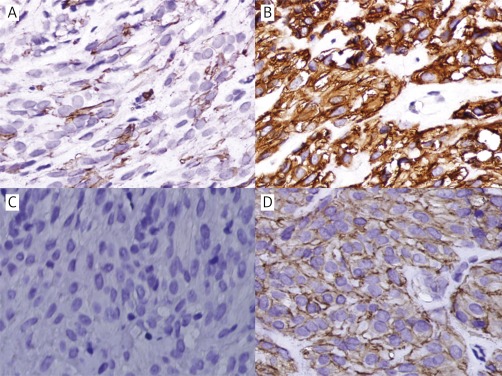

Due to the patient's condition, hepatectomy could not be performed, and a US-FNAB from the liver mass was taken. Histologically the tumor consisted of spindle cells with pleomorphic nuclei, commonly vacuoles beside the nuclei and abundant intercellular collagen (Figures 2A–B). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the spindle cells were positive for CD117 (Figure 3 B), CD34 (Figure 3 A), discovered on GIST1 (DOG-1) (focal) (Figure 3 D), SMA (Figure 2 C), and vimentin (Figure 2 D), while they were negative for CK (Figure 3 C) and S-100 (figure not shown). All these results indicated that the diagnosis was extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor. The tumor's mitotic activity could not be evaluated because of the small amount of examined material. KIT gene mutation analysis was not performed due to its non-availability at our institute.

Figure 2.

Histological and immunohistochemical findings of hepatic EGIST. A – The tumor is composed of spindle cells (hematoxylin and original magnification 200×).B – The spindle cells show pleomorphic nuclei, commonly vacuoles beside the nuclei and abundant intercellular collagen (hematoxylin and original magnification 400×).C – The tumor cells test positive for SMA (original magnification 400×).D – Vimentin is diffusely and strongly positive in the tumor cells (original magnification 400×)

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical findings of hepatic EGIST. A – CD34 positive in tumor cells (original magnification 400×).B – CD117 positive in tumor cells (original magnification 400×).C – CK negative in tumor cells (original magnification 400×).D – DOG-1 focally positive in tumor cells (original magnification 400×)

We advised the patient to take imatinib mesylate (Glivec), but he refused because of financial problems, and was discharged 13 days later.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is a common tumor of the gastrointestinal tract, which mainly occurs in the stomach. When this kind of neoplasm develops outside the gastrointestinal tract, it is defined as EGIST. Metastasis of GIST to the liver is very common, while primary GIST of the liver is extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 5 cases of primary hepatic EGIST have been reported previously in English [13–17] (Table I). There is a distinct male predominance, and their age ranges from 17 to 79 years, average 47.7 years. The majority have a large tumor size, only one under 10 cm. Four of 6 cases have a spindle cell type. Both CD117 and CD34 have only one case that is negative. The mitotic rate and outcome are hard to analyze. Due to the particularity of hepatic EGIST, it should be diagnosed differentially with primary or metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma, angiomyolipoma, leiomyosarcoma, or malignant melanoma. HMB-45 and PKCθ were recommended in immunohistochemical analysis, so as to exclude the mimics mentioned above [17].

Table I.

Hepatic EGIST reported in the literature

| Author, year | Age [years] | Gender | Tumor size [cm] | Cell type | Mitosis/50HPFa | CD117 | CD34 | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamamoto et al., 2010 | 70 | Male | 20 | Epithelioid | 1 | – | + | NAb |

| Luo et al., 2009 | 17 | Male | 5.1 | Spindle | NA | + | + | Alive and well 3 months |

| Ochiai et al., 2009 | 30 | Male | > 10 | Mixed | 75 | + | + | Alive and well 42 months |

| De Chiara et al., 2006 | 37 | Male | 18 | Spindle | 20 | + | – | Alive and well 36 months |

| Hu et al., 2003 | 79 | Female | 15 | Spindle | 4/10HPF | + | + | Recurrence 16 months |

| The current study | 53 | Male | 20 | Spindle | NA | + | + | NA |

HPF – high-power field

NA – not available

US-FNAC is the quickest and least painful way to obtain an accurate tissue diagnosis of a lump anywhere in the body. There are three steps in US-FNAC: firstly, the position, size and adjacent structure of the lesion are evaluated by ultrasound; secondly, two or more samples are taken with a 23-gauge or 25-gauge needle; lastly, the obtained samples are stained and examined by a pathologist. It has multiple advantages compared to open biopsy, which is not only inexpensive and minimally invasive but is also performed simply and easily. Furthermore, it allows surgery or neoadjuvant treatment to be performed expeditiously with a confirmed preoperative diagnosis. An accurate diagnosis is made with the combination of clinical examination, radiology and FNAC. Although EGIST is rare, it also could be diagnosed by this technique. Rao et al. [26] reported a case and reviewed three cases of pancreatic EGIST, which were diagnosed by US-FNAC. Luo et al. [15] showed that there was no exception on hepatic EGIST. The present case revealed that the biopsy samples were enough for cytological analysis, although the mitotic rate could not be determined.

In order to understand EGIST more clearly, we have reviewed several quite large studies [1–4, 27–30] (Table II) published recently. When these data are summarized together, some similarities can be seen distinctly. The incidence of EGIST is 5%-7% of cases of GIST [4, 28], with a female predominance (64.9%, 98/151), and the most frequent lesion sites are the mesentery, omentum and retroperitoneum [1–4]. The median age is 58.5 years, which is similar to jejunal and ileal GISTs (59 years) [31]. Due to EGIST being outside of the gastrointestinal tract, there are no common symptoms such as bleeding or obstruction. Furthermore, the abdominopelvic cavity and retroperitoneum have enough room for a neoplasm to grow. Thus most of the cases presented a tremendous mass when first detected, with median size of 13.5 cm. Whether the tumor size is a prognostic factor or not, it should be taken into account. Reith et al. [2] found that there were no significant differences between large (> 10 cm) and small (≤ 10 cm) tumors in outcome. The cell morphological pattern of EGIST is predominantly spindle (71 cases) or epithelioid (54 cases). Three studies [1–3], in which the number of patients was more than 20, were in accord with the figure. Spindle cell EGIST should be diagnosed differentially with smooth muscle tumors, schwannoma, solitary fibrous tumor and sarcomatoid carcinoma, while epithelioid EGIST should be diagnosed differentially with metastatic melanoma, carcinoma, clear cell sarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma [32]. More than one third (55/135) of cases displayed a mitotic index more than 5 per high-power field (HPF). Yamamoto et al. [3] revealed that a high mitotic rate (≥ 5/50 HPF) had significantly shorter disease-specific survival than a low rate (< 5/50 HPF) (p = 0.015). Almost 100% were positive for CD117 [2–4, 29]. We think that it may be because most of them are retrospective studies. The patients were used to being easily misdiagnosed with other diseases. With this type of issue, CD117 was recommended as a selection criterion. CD117-negative tumors should be taken seriously; it still cannot exclude EGIST. Demetri et al. [32] recommended using DOG-1 as a candidate when CD117 immunostaining and mutation testing for KIT and PDGFRA were all negative. About 57.1% (84/147) of patients were CD34-positive, which was lower than GIST (81%) [33]. Other antibody markers were different in these studies; thus it was hard to analyze. Considering the follow-up data from different studies, it is very difficult to reach a persuasive conclusion. However, there is a trend that EGIST is an aggressive group with worse outcome.

Table II.

Summary of clinicopathological features of seven case series of EGIST

| Author, year | Patients (n) | Age [years] Mean (range) | Gender F/Ma | Location A/R/Pb | Tumor size [cm] Mean (range) | Cell type S/E/Mc | Mitosis/50 HPFd> 5/n | CD117 (+)/ne | CD34(+)/ne | Follow-up [months] Mean (range)/ne |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barros et al., 20114 | 9 | 56.8 (36-81) | 7/2 | 5/3/1 | 18 (8.5-27) | NAf | 2/9 | 9/9 | 5/9 | 26.4 (4-114)/9 |

| Padhi et al., 201027 | 9 | 56.1 (38-72) | 8/1 | 9/0/0 | 14.7 (2.5-35) | NA | 3/9 | 6/9 | 6/7 | 16.3 (1-30)/7 |

| Li et al., 200529 | 14 | 55 (33-79) | 9/5 | 14/0/0 | 12.4 (3.5-29) | 9/2/3 | 8/14 | 14/14 | 8/14 | 45 (18-96)/13 |

| Yamamoto et al., 20043 | 39 | 59 (30-88) | 24/15 | 17/17/5 | 13.5 (3-35) | 21/18/0 | 17/39 | 33/39 | 24/39 | 56 (5-192)/33 |

| Hou et al., 200330 | 9 | 61.7 (38-72) | 7/2 | 7/2/0 | 12.9 (5-23) | 7/1/1 | 5/9 | 9/9 | 5/9 | 68.8 (18-132)/5 |

| Reith et al., 20002 | 48 | 58 (31-80) | 32/16 | 40/8/0 | 12 (2.1-32) | 20/24/4 | 11/32g | 48/48 | 24/48 | 24 (4-84)/31 |

| Miettinen et al., 19991 | 23 | 60.5 (31-80) | 11/12 | 23/0/0 | 15 (2.3-36) | 14/9/0 | 9/23 | 13/14 | 12/21 | 31.5 (6-102)/16 |

| Summary | 151 | 58.5 (30-88) | 98/53 | 115/30/6 | 13.5 (2.1-36) | 71/54/8 | 55/135 | 132/142 | 84/147 | 38.4 (1-192)/114 |

F/M – female/male

A/R/P – intra-abdominal/retroperitoneum/pelvis

S/E/M – spindle/epithelioid/mixed

HPF – high-power field

n – number of patients investigated in this subject

NA – not available

32 out of 48 patients were analyzed in this subject

In conclusion, we have presented a case of hepatic EGIST diagnosed by US-FNAC. The incidence of EGIST is low, and it has a younger age of diagnosis and large tumor size. The mitotic index can be a prognostic factor; however, tumor size still needs more proof. Furthermore, EGIST can be misdiagnosed for other diseases, and clinicians should take it seriously.

References

- 1.Miettinen M, Monihan JM, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1109–18. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reith JD, Goldblum JR, Lyles RH, Weiss SW. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:577–85. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K, et al. c-kit and PDGFRA mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the soft tissue) Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:479–88. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barros A, Linhares E, Valadao M, et al. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumors (EGIST): a series of case reports. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:865–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long KB, Butrynski JE, Blank SD, et al. Primary extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of the pleura: report of a unique case with genetic confirmation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:907–12. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9f18f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cecka F, Jon B, Ferko A, Subrt Z, Nikolov DH, Tycova V. Long-term survival of a patient after resection of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising from the pancreas. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:330–2. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao RN, Vij M, Singla N, Kumar A. Malignant pancreatic extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor diagnosed by ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology. A case report with a review of the literature. JOP. 2011;12:283–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vij M, Agrawal V, Pandey R. Malignant extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the pancreas. A case report and review of literature. JOP. 2011;12:200–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang F, Jin C, Fu D, Ni Q. Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the pancreas: clinical characteristics, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:739–40. doi: 10.1002/jso.21833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirabayashi K, Fujihira T, Oyamada H, et al. First case of primary phyllodes tumor of the pancreas: case report and findings of immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:587–93. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0893-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Showalter SL, Lloyd JM, Glassman DT, Berger AC. Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the pancreas: case report and a review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143:305–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaura K, Kato K, Miyazawa M, et al. Stromal tumor of the pancreas with expression of c-kit protein: report of a case. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:467–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Chiara A, De Rosa V, Lastoria S, et al. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver with lung metastases successfully treated with STI-571 (imatinib mesylate) Front Biosci. 2006;11:498–501. doi: 10.2741/1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu X, Forster J, Damjanov I. Primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1606–8. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-1606-PMGSTO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo XL, Liu D, Yang JJ, et al. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3704–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochiai T, Sonoyama T, Kikuchi S, et al. Primary large gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39:633–6. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3885-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto H, Miyamoto Y, Nishihara Y, et al. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver with PDGFRA gene mutation. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:605–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JK, Choi SH, Lee S, Min KO, Yun SS, Jeon HM. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the gallbladder. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:763–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.5.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sereg M, Buzogány I, Gonda G, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as a hormonally inactive adrenal mass. Endocrine. 2011;39:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin HS, Cho CH, Kum YS. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of the urinary bladder: a case report. Urol J. 2011;8:165–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mekni A, Chelly I, Azzouz H, et al. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of the urinary wall bladder: case report and review of the literature. Pathologica. 2008;100:173–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krokowski M, Jocham D, Choi H, Feller AC, Horny HP. Malignant extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of bladder. J Urol. 2003;169:1790–1. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000062606.13148.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yinghao S, Bo Y, Xiaofeng G. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor possibly originating from the prostate. Int J Urol. 2007;14:869–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YJ, Jeong YY, Kim SM. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor arising from the vagina: MR findings. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1860–1. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weppler EH, Gaertner EM. Malignant extragastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting as a vaginal mass: report of an unusual case with literature review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:1169–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao RN, Vij M, Singla N, Kumar A. Malignant pancreatic extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor diagnosed by ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology: a case report with a review of the literature. J Pancreas. 2011;12:283–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padhi S, Kongara R, Uppin SG, et al. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the pancreas: a case report with a review of the literature. JOP. 2010;11:244–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W, Peng Z, Xu L. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the rectovaginal septum: report of an unusual case with literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li ZY, Huan XQ, Liang XJ, Li ZS, Tan AZ. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors arising from the omentum and mesentery [Chinese] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2005;34:11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou YY, Sun MH, Wei YK, et al. Clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study of intra-abdomen extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors [Chinese] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2003;32:422–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miettinen M, Makhlouf H, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the jejunum and ileum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 906 cases before imatinib with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:477–89. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Antonescu CR, et al. NCCN Task Force report. Update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(Suppl):S1–41. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:52–68. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146010.92933.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]