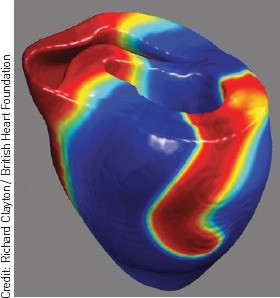

Computer simulation of electrical activity in the heart during the onset of cardiac arrest. Instead of regular activity controlled by the pacemaker of the heart, electrical activation (shown in red) has looped around into a spiral that will fragment, resulting in lethal electrical anarchy. This type of computational model gives a powerful insight into the mechanisms of normal and abnormal electrical activity in the heart while reducing the need for experiments using animal tissue.

Taking medication is arguably one of the most common behavioural changes that GPs and other healthcare professionals require patients to make. Yet taking medicines is a complex behaviour, involving at least three stages — prescribing, dispensing, and the actual taking of the medication — that must all be effectively carried out for treatment to be successful, and in all of which personal and interpersonal factors, and the exchange and use of information play important parts. The impact on patients who fail to take their medicines correctly can be devastating in terms of their health and quality of life, and the burden to them and to society includes the cost of poorly managed risk factors, under treated symptoms, poor health outcomes, and inefficient use of NHS resources. A recent Cochrane review, Interventions for Enhancing Medicine Adherence, concluded that improved adherence to prescribed medication may have a greater impact on clinical outcomes than improvement in treatments.1

THE COST OF NON-ADHERENCE

The cost to the NHS of cardiovascular drugs alone is £2.8 billion, and this accounts for 20% of healthcare costs associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD).2 It is estimated that between one-half and one-third of all medicines prescribed for long-term conditions are not taken as recommended,3 and non-adherence to medication costs the NHS up to £100 million a year.3 The British Heart Foundation (BHF) YouGov Survey has recently found that one in three people with high cholesterol and one in four people with high blood pressure do not take their medication correctly (BHF, YouGov, unpublished data, 2011). Adherence is defined as ‘the extent to which a patient's behaviour matches agreed recommendations from the prescriber’.5 It is implicit that there should be an agreement between the professional and the patient, and the patient is free to decide what to do about the prescriber's recommendation. The term adherence is preferred to compliance, which lacks the implication that patients are free to make informed but divergent choices about prescribing recommendations. The term concordance has also been used almost synonymously to emphasise the need for negotiation between prescribers and patients and the positive impact on adherence of a management plan agreed (concordant) between both parties.6,7

WHOSE RESPONSIBILITY IS IT?

There are many reasons for non-adherence, but they should not all be seen as the patient's problem. Some of these include problems with the drug regime, the cost of prescription charges, poor information about the logistics and benefits of medicine taking, unpleasant side effects, cognitive and sensory impairment, and confusion caused by polypharmacy. The BHF YouGov data indicate that the main reasons for people with high cholesterol or high blood pressure not taking their medication are that they do not have symptoms or they have problems with side effects. In this issue of the BJGP Murray and colleagues report the results of a systematic review of influences on lifestyle modification in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease, and identify a wide range of factors, among which five main themes emerged. These were to do with transport and mobility, information and communication, friends and family support, emotional issues, and psychological and spiritual beliefs.8

IMPROVING NON-ADHERENCE

Given the magnitude and importance of the problems surrounding adherence, what steps might reasonably be taken to improve the situation? The evidence on which to base interventions is still surprisingly limited, and a Cochrane overview of 37 systematic reviews of interventions to improve medicines use9 concluded that ‘promising’ interventions to improve adherence include self-monitoring and self-management, simplified dosing, and interventions directly involving pharmacists. Other candidate strategies were reminders, education combined with self-management skills training, financial incentives, and lay health worker interventions. Some of these may well have implications for the promotion of adherence to cardiovascular medications. The need to provide clear information to patients is well-exemplified in this month's paper from Wald and colleagues, in which they describe a simple algorithm to enable the reduction in a given value of body mass index to be converted into a more readily understood weight reduction target.10

The BHF is currently running a social marketing campaign reminding heart patients and people with risk factor conditions, such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure, about the importance of taking their medication correctly. To reach out to the target audience, the BHF is using the face and voice of comedy legend Tommy Cooper, who famously and tragically died of a heart attack on stage. We hope that the radio advertisements, magazine inserts, and leaflets we drop through people's doors featuring Tommy will increase awareness of the importance of adherence (http://www.bhf.org.uk/tommy).

The achievement of adherence to medication has many implications for general practice. Another finding of the BHF YouGov survey was that one in five people would never tell their GP if they were no longer taking their medication as prescribed. Nearly one-third said they felt their GP was too busy to give them the time they needed. Many non-adherent patients do not tell their GP that they are not taking their medications because of shame, embarrassment, or awkwardness and patients tell us that they often feel judged by GPs. These data remind us that we should not underestimate the number of people who might not be taking their medication and emphasise the importance of including a discussion about adherence at medication reviews.

The Royal College of General Practitioners’ position paper Promoting Continuity of Care in General Practice11 highlights the importance of continuity, and includes evidence that personal and organisational continuity of care contributes to adherence to drug regimes.7,12 The RCGP's Care Planning Initiative, which aims to improve outcomes for patients with long-term conditions, also has a major focus on patient–professional engagement and shared decision-making about medication,3 and using techniques such as goal setting and action planning with patients.

Finally, there is a need for more research into effective interventions that will improve adherence. Our understanding of the reasons for non-adherence is still imperfect. Older patients with multimorbidity requiring multiple medications are a particularly important and challenging group, and we need to develop better ways of supporting adherence among these patients, as well as having a better understanding of some of the complex interactions between medications in those with long-term comorbidity.

In conclusion, we need to improve outcomes for patients, reduce the societal costs of under-treated illness, and reduce waste in the NHS at a time of financial austerity, by addressing the causes of non-adherence. This is an opportunity to make real improvements in line with the NHS Quality Innovation Productivity and Prevention agenda.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scarborough P, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, et al. Coronary disease statistics. Oxford: University of Oxford and the British Heart Foundation Health Promotion Research Group; 2010. http://www.bhf.org.uk/idoc.ashx?docid=9ef69170-3edf-4fbb-a202-a93955c1283d&version=-1 (accessed 14 May 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, et al. Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine-taking. Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service delivery and organisation R & D. Southampton: NCCSDO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. Pharmacy in England, building on strengths — delivering the future. London: TSO; 2008. Cm 7341. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunes V, Neilson J, O'Flynn N, et al. Clinical guidelines and evidence review for medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Britten N. ‘Doing prescribing’: how clinicians might work differently for better, safer care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(Suppl 1):i33–36. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_1.i33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson FA, Cox K, Britten N, Dundar Y. A systematic review of the research on communication between patients and health care professionals about medicines: the consequences for concordance. Health Expect. 2004;7(3):235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray J, Honey S, Hill K. Individual influences on lifestyle change to reduce vascular risk: a qualitative literature review. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X649089. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp12X649089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan R, Santesso N, Hill S, et al. Consumer-oriented interventions for evidence-based prescribing and medicines use: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(5) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007768.pub2. CD007768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wald NJ, Bestwick JP, Morris JK. Body weight reduction to avoid the excess risk of type 2 diabetes. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X649098. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp12X649098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill AP, Freeman GK. Promoting continuity of care in general practice. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ettlinger PR, Freeman GK. General practice compliance study: is it worth being a personal doctor? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282(6271):1192–1194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6271.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathers N, Roberts S, Hodkinson I, Karet B. Care planning improving the lives of people with long term conditions. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2011. [Google Scholar]