Abstract

Pandemic infection or reemergence of Enterovirus 71 (EV71) and coxsackievirus A16 (CVA16) occurs in tropical and subtropical regions, being associated with hand-foot-and-mouth disease, herpangina, aseptic meningitis, brain stem encephalitis, pulmonary edema, and paralysis. However, effective therapeutic drugs against EV71 and CVA16 are rare. Kalanchoe gracilis (L.) DC is used for the treatment of injuries, pain, and inflammation. This study investigated antiviral effects of K. gracilis leaf extract on EV71 and CVA16 replications. HPLC analysis with a C-18 reverse phase column showed fingerprint profiles of K. gracilis leaf extract had 15 chromatographic peaks. UV/vis absorption spectra revealed peaks 5, 12, and 15 as ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol, respectively. K. gracilis leaf extract showed little cytotoxicity, but exhibited concentration-dependent antiviral activities including cytopathic effect, plaque, and virus yield reductions. K. gracilis leaf extract was shown to be more potent in antiviral activity than ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol, significantly inhibiting in vitro replication of EV71 (IC50 = 35.88 μg/mL) and CVA16 (IC50 = 42.91 μg/mL). Moreover, K. gracilis leaf extract is a safe antienteroviral agent with the inactivation of viral 2A protease and reduction of IL-6 and RANTES expressions.

1. Introduction

Kalanchoe gracilis (L.) DC, “Da-Huan-Hun” in Chinese, is a traditional Chinese medicinal herb belonging to the Crassulaceae family, a folk medicine commonly used for treating injuries, pain, fever, and inflammation in Taiwan [1, 2]. Extracts of K. gracilis have high amounts of polyphenol and flavonoid contents that may generate potential antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activities [2, 3]. Identified constituents include coumarin, bufadienolides, flavonoids (e.g., teolin, quercetin, quercitrin, kaempferol and eupafolin), and glycosidic derivatives of eupafolin [4, 5]. The latter is a vital bioactive compound shown to possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in lipopolysaccahride-treated RAW264.7 cells as well as antiproliferating effect against HepG2 cells [3]. Coumarin-based compounds are reported with antiviral activities against Hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) [6–10]. 3-Phenyl coumarin-based compounds were previously reported to bind with viral protein R (Vpr) and inhibit Vpr-dependent HIV replication in human macrophages [10]. Chiang et al. [7] also proved less than 1 μM of synthetic analogue of bis- or tetra-coumarin required to inhibit HIV-1 integrate by half. Flavonoids are reported to hold a broad spectrum of antiviral activity efficiently inhibiting replication of human rhinovirus, Sabin type 2 polio, Hepatitis A, coxsackievirus B4, and echovirus 6 [11–14]. Extract of Kalanchoe farinacea, another species of the Crassulaceae family, has shown antiviral activity against influenza A and herpes simplex virus Type 1 in vitro [15]. Bufadienolides identified from leaves of two other Crassulaceae plants, Kalanchoe pinnata and K. daigremontiana x tubiflora, inhibit activation of Epstein-Barr virus early antigen in Raji cells [16]. Together with antiviral data of related compounds and Crassulaceae plants, K. gracilis offers a valuable source of antiviral agents.

Enteroviruses (EVs) are members of the Picornaviridae family, which have in common a 7.4 kb single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome [17]. Enterovirus genome encodes a single large polyprotein cleaved by enteroviral 2A and 3C proteases. After protein synthesis, viral polyproteins are cleaved into four capsid (VP1 to VP4) and seven nonstructural proteins (2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D). Many crucial pathogens are enteroviruses: for example, polioviruses, coxsackievirus A (CVA) and B (CVB), echovirus EV68, EV69, EV70, EV71. CVA and EV71 are independent aetiological agents of hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), myocarditis, ocular conjunctivitis, herpangina, aseptic meningitis, or severe neurological complications, such as encephalitis and poliomyelitis-like paralysis [18]. Particularly, EV71-induced brainstem encephalitis has poor prognosis with high mortality [19]; EV71 outbreaks have been reported in countries in the Western Pacific, Sweden, and Australia [19–22]. Such epidemics in Taiwan caused 78 deaths in 1998 [23–26], 25 deaths in 2000, and 26 deaths in 2001 [21]. Importantly, cocirculations of EV71 and CVA appear in serious HFMD outbreaks in China, Taiwan, and Malaysia [26–28]. In Taiwan, coxsackievirus A16 (CVA16) is a major serotype of CVA isolates identified in HFMD outbreaks [26, 28]. Global poliovirus vaccination program plans to eradicate poliovirus diseases like severe poliomyelitis worldwide; yet no antiviral drug has been approved by FDA for treatment of EV infection. Strategy to prevent or treat EV infection proves essential, especially for EV71 and CVA16.

This study investigated in vitro antiviral activity of K. gracilis leaf extract against EV71 and CVA16, using in vitro models in pretreatment before virus adsorption, simultaneous treatment during infection and posttreatment after virus adsorption. All showed significantly less viral replication in vitro; treatment at early and late stages showed potent inhibition. This study also examined possible antiviral mechanisms: for example, inhibition of in vitro and cell-based 2A protease activity, anti-inflammatory effect on expression of virus-induced inflammatory genes, activation of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, and NF-κB signaling pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses and Cells

EV71 and CVA16 were obtained from clinical isolates in the Clinical Virology Laboratory, China Medical University Hospital at Taichung, Taiwan. RD cells (ATCC accession no. CCL-136) were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco). All media were supplemented with 100 U/mL of penicillin and streptomycin and 2 mM of l-glutamine. HeLa-G2AwtR cells were derived from HeLa cells containing pG2AwtR plasmid that encodes an FRET probe as well as the fusion protein of red fluorescent protein (DsRed)—2Apro cleavage motif—green fluorescent protein (GFP) as described by Tsai et al. [29]. Cells were cultured in Modified Eagle's Medium (MEM; Gibco) with 10% FBS and 20 μg/mL zeocin.

2.2. Preparation of K. gracilis Leaf Juice Extract

K. gracilis was collected from farmlands and gardens in Chiayi County, Taiwan as described in Flora of Taiwan and identified by Professor Hsin-Fu Yen from the National Museum of Natural Science at Taichung, Taiwan. Fresh K. gracilis leaves were cold-pressed, resulting leaf juice filtered through Whatman No. 1 paper, then lyophilized in a freeze dryer (IWAKI FDR-50P). This powder of leaf juice extract was stored in sterile bottles and kept in −20°C freezer.

2.3. Fingerprint Analysis by HPLC

For analyzing HPLC fingerprint profiles, filtered extract of K. gracilis leaf of ethyl acetate layer or the marker mixture of ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol (10 μL) was injected directly into the HPLC instrument (Shimadzu LC-10A) with a C-18 reverse phase column. Ferulic acid was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co (St. Louis, Mo, USA). Quercetin was purchased from Alfa Aesar-A Johnson Matthey Company. Kaempferol was purchased from Extrasynthese (France). Separation was conducted with a gradient elution of 0.25% formic acid and acetonitrile (40% between 0 and 9 min, 40–60% between 9 and 30 min) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. Chromatographic peaks were detected at 260/360 nm with a 2996 PDA detector.

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

For cell viability, RD cells were cultured overnight on 96-well plates. Medium containing 0, 1, 50, 250, 500, or 1000 μg/mL of K. gracilis leaf extract was added and incubated for 24 and 48 hours, followed by MTT assay. Survival rates of cells were calculated as the ratio of optical density at 570–630 nm (OD570–630) of treated cells to OD570–630 of untreated cells. Quintuplicate wells were analyzed for each concentration. The data represented the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Cytotoxic concentration of 50% toxic effect (CC50) was determined using a computer program (provided by John Spouge, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health). Ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol at concentrations of 1, 10, 50, 100, and 500 μg/mL were also tested for cytotoxicity.

2.5. Cytopathic Effect (CPE) Reduction Assay

RD cells (4 × 105 RD cells per well) were seeded to the 6-well plate. Next day, EV71 or CVA16 at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 was mixed with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 2% FBS alone or medium with 100 μg/mL of K. gracilis leaf extract before adding to the RD cells to incubate for 24 and 48 h at 37°C. Cell morphology was observed and photographed under microscopy.

2.6. Plaque Reduction Assay

RD cells (4 × 105 RD cells per well) were seeded to the 6-well plates. Next day, cells were infected with EV71 or CVA16 (100 pfu) in the absence or presence of K. gracilis leaf extract at 10, 50, or 100 μg/mL or the marker compound (quercetin, ferulic acid, and kaempferol) at 0.1, 1, 10, and 50 μg/mL 1 h at 37°C. Then, 2 mL of medium containing 3% agarose was overlaid onto the cells and incubated for 2 days at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. At the end of incubation, cells were stained with 0.1% Crystal Violet. Ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol at the concentrations of 0.1, 1, 10, and 50 μg/mL were also tested for plaque reduction. The concentrations that reduced the number of plaques by 50% (IC50) were then determined. The therapeutic index (TI) was determined by the ratio of CC50 to IC50.

2.7. Virucidal Activity Assay

EV71 or CVA16 (104 pfu) was mixed with test compounds of various concentrations (0, 50, and 100 μg/mL) or medium and incubated for 30 min at room temperature, then serial dilutions of the mixture were performed using the plaque assay. The residual infectivity was measured as described in the plaque assay.

2.8. Virus Yield and Time-of-Addition Assays

K. gracilis leaf extract was added to RD cells before (30 min pretreatment), during (simultaneous treatment), and after (30 min posttreatment) the viral infections of EV71 and CVA16 at the titer of 300 pfu. 48 h after infection, culture media were collected and RNA genomes were extracted by QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Real-time RT-PCR was performed with specific primers, SYBR green PCR Master Mix, and SYBR green I dsDNA binding dye. Oligonucleotides for VP1 were forward primer 5′-GGCCCCTGAATGCGGCTAATCC-3′ (nt 458–480) and reverse primer 5′-GCGATTGTCA CCATWAGCAGYCA-3′ (nt 603–581) as described in the report of Oberste et al. [30]. PCR product level was monitored with an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). For comparing the viral RNA load in the cultured media, a delta Ct value was calculated by subtracting the Ct value for viral load in cultured media of K. gracilis leaf-extract-treated infected cells from the Ct value for viral load in cultured media of infected cells without treatment. If the delta Ct value was greater than 3.3, indicating 50 μg/mL of K. gracilis leaf extract had more than 1-log reduction (equal to 90% effective concentration [EC90]) in virus RNA loads.

2.9. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Assay

HeLa-G2AwtR cells (1 × 106 cells per well) expressing the FRET probe were seeded to the 6-well tissue culture plates and infected with EV71 or CVA16 (1 × 106 pfu). After 1 h of adsorption, the inoculum was aspirated and 200 μL of modified Eagle's medium containing 2% FBS alone or medium with 1, 10, 50, 100, or 150 μg/mL of K. gracilis leaf extract was added to each well. Cells were harvested 48 h after infection, and lysates were transferred to 96-well plates for fluorescence. The fluorescent intensity of the FRET probes was measured by a fluorescent-plate reader with an excitation wavelength at 390/20 nm (for GFP2 at 510/10 nm) and an emission wavelength at 590/14 nm (for DsRed2), in which DsRed2 was excited by the emission of GFP2 at 510/10 nm. The data presented are mean values of three independent experiments, and the error bars represent standard deviations.

2.10. Construction, Expression, and Purification of EV71 2A Protease

The gene encoding EV71 2A protease was amplified using PCR with cDNA of EV71 isolate CMUH01. The forward primer 5′-GCGCGGATCCGGGAAATTCGGTCAGCAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GCGCCTCGAGCTGCTCCATCGCTTCCTC-3′, which contain BamHI and XhoI restriction enzyme sites (underlined), were used for C-terminal His-tagged protease. PCR products were digested with BamHI and XhoI, and the DNA fragment was cloned into pET24a (Novagen). The plasmid containing the protease gene was subsequently transformed into E. coli Origami B (DE3) (Novagen) for protein expression. A 10 mL overnight culture of a single colony was used to inoculate 400 mL of fresh LB medium containing 25 μg/mL kanamycin. Cells were grown to an A600 of 0.6 and induced with 1 mM IPTG. After IPTG induction overnight, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 min, and then resuspended in a denaturing buffer (10 mM imidazole, 8 M urea and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol) before subjecting to sonication. Separation of the supernatant was conducted in Ni-NTA column, and His-tagged 2A protease was allowed to renature slowly by gradient washing with refolding buffer (10 mM imidazole and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol) overnight. Finally, recombinant 2A protease was eluted with 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 300 mM imidazole. The concentration of purified protein was determined using Bio-Rad protein assay.

2.11. In Vitro 2A Protease Activity Assay

In the protease activity assay, 2A protease was designed to interact with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). HRP is a commercially available substrate, and its Leu-Gly pairs at residues 122-123 correspond to the cleavage site by 2A protease. To examine the most suitable concentration of 2A protease for interaction with HRP, 2A proteases of various concentrations ranging from 1 μg/mL to 150 μg/mL were each added and incubated with 1 μg/mL of HRP for 2 h at 37°C. Mixtures were then developed with ABTS/H2O2 and measured at OD405. The extract of K. gracilis leaf was tested for anti-EV71 2A protease activity, thus it was incubated with HRP for 2 h at 37°C in 96-well plates in vitro. The remaining activity of HRP in each reaction was determined with a chromogenic substrate ABTS/H2O2 and the intensity of the developed color was measured at 405 nm. Percentage of inhibition of EV71 2A protease activity was calculated by the following equation: (OD405HRP+drug+2Apro − OD405HRP+2Apro)/(OD405HRP only − OD405HRP+2Apro) × 100%.

2.12. Quantification of Proinflammatory Gene Expression Using Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from RD cells with or without the treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract and with or without virus infection via purification kit (PureLink Micro-to-Midi total RNA Purification System, Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 1000 ng total RNA with oligo dT primer and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). To gauge expression in response to treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract and/or virus infection, a two-step RT-PCR using SYBR Green I was used. The following oligonucleotide primer pairs were used in the present study for the detection of cytokines, including (1) forward primer 5′-TCCCCATATTCCTCGGAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GATGTACTCCCGAACCCA-3′ for human RANTES, (2) forward primer 5′-ATGCCCCAAGCTGAGAACCAAGACCCA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TCTCAAGGGGCTGGGTCAGCTATCCCA-3′ for human IL-10, (3) forward primer 5′-GATGGATGCTTCCAATCTGGAT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGTTCTCCATAGAGAACAACATA-3′ for human IL-6, (4) forward primer 5′-CTCTAGAGCACCATGCTACAGAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TGGAATCCAGGGGAAACACTG-3′ for human IL-1α, and (5) forward primer 5′- CATGCGTTTCCGTTACAAGTGCGA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TGGGTGCGTCTTAGTGGTATCTGT-3′ for human NF-κB. In addition, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA, a housekeeping gene, was measured using 5′-AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC-3′ and 5′-GCCCCA ATACGACCAAATCC-3′ as forward and reverse primers. Real-time PCR reaction mixture contained 2.5 μL of cDNA (reverse transcription mixture), 200 nM of each primer in SYBR Green I master mix (LightCycler TaqMAn Master, Roche Diagnostics). PCR was performed by an amplification protocol consisting of 1 cycle at 50°C for 2 min, 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1 min. Specific products were amplified and detected in ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (PE Applied Biosystems), and relative changes in mRNA levels of indicated genes were gene normalized by housekeeping gene GAPDH.

2.13. Western Blot Analysis

RD cells were infected with the virus (8 × 105 pfu) in the presence or absence of K. gracilis leaf extract. The lysate proteins of RD cells were dissolved in 2x SDS-PAGE sample buffer without 2-mercaptoethanol, boiled for 10 min, and then separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels before being transferred to nitrocellulose paper. Resultant blots were blocked with 5% skim milk then reacted with properly diluted monoclonal antibodies including anti-ERK1/2, anti-phospho-ERK1/2, anti-p38 MAPK, anti-phospho-p38 MAPK, anti-p65, anti-phospho-p65, anti-caspase 9 (Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-β-actin. The immune complexes were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies followed by enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

2.14. In Vivo Anti-EV71 Assay

Suckling mice of 1-day-old were intraperitoneally inoculated with EV71 (1.7 × 105 pfu) and intraperitoneally injected with K. gracilis leaf extract (0, 1, 2 mg/kg) once on day 1, 3, 5, 7 after-infection. 3 mice from each group were sacrificed on day 2, 4, 6, and 8. Intestine samples were collected for detection of virus loads using real-time RT PCR.

2.15. Statistical Analysis

ANOVA analysis using SPSS program (version 10.1, SPSS Inc., IL, USA) or Scheffe test was used to analyze all data. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Fingerprint Profiling of K. gracilis Leaf Extract

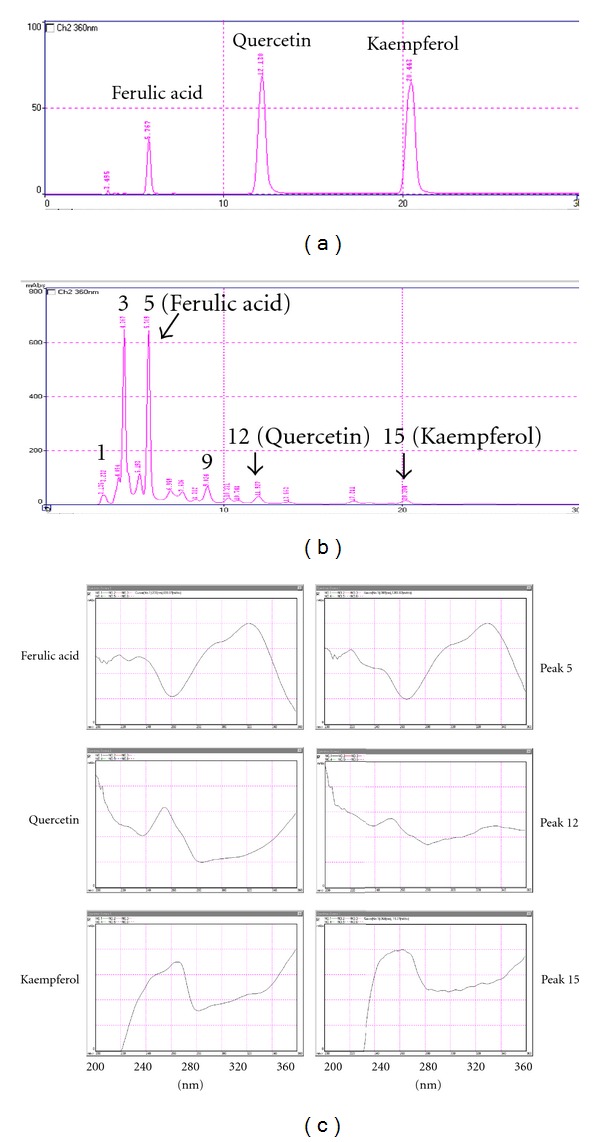

To determine the fingerprint of K. gracilis leaf extract, the ethyl acetate layer of filtered leaf extract and marker components of ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol as well were analyzed using HPLC with a C-18 reverse phase column (Figure 1). The retention time was found at 5.74 min for ferulic acid, 12.13 min for quercetin, and 20.44 min for kaempferol at 360 nm (Figure 1(a)). HPLC chromatographic peaks of K. gracilis leaf extract of ethyl acetate layer indicated the retention times of peaks 5, 12, and 15 were identical to those of ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol, repectively (Figure 1(b)). UV absorption spectra (200–360 nm) of peaks 5, 12, and 15 were identical as compared to the marker components of ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol, respectively (Figure 1(c)). HPLC and UV absorption analyses revealed fingerprint profiling as well as the maker components in K. gracilis leaf extract.

Figure 1.

HPLC fingerprint profiles and UV/vis absorption spectra of K. gracilis leaf extract of ethyl acetate layer and marker components. Marker components of ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol (a) and K. gracilis leaf extract of ethyl acetate layer (b) were analyzed using HPLC with a C-18 reverse phase column. Eluents were detected at 360 nm. Maximum absorption wavelengths of ferulic acid, quercetin, kaempferol, and chromatographic peaks 5, 12, and 15 were measured by UV/vis absorption spectra (200–360 nm).

3.2. Cytotoxicity of K. gracilis Leaf Extract in RD Cells

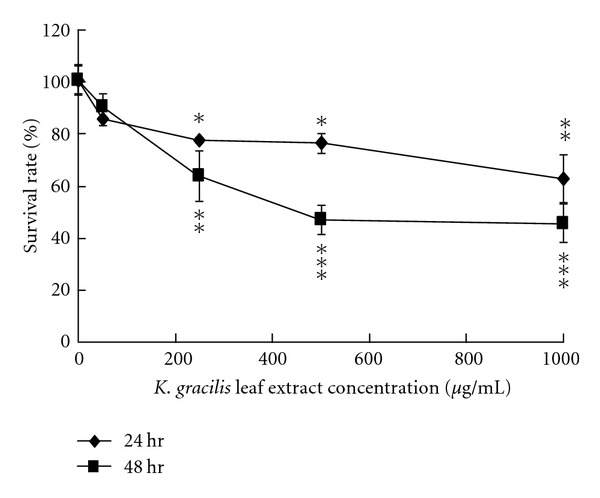

To evaluate the cytotoxicity of K. gracilis leaf extract, RD cells were treated with K. gracilis leaf extract at the concentration range of 1–1000 μg/mL. In vitro cytotoxicity assay showed that K. gracilis leaf extract was not cytotoxic to RD cells in the concentration range of 1–500 μg/mL 24 and 48 h posttreatment (Figure 2). 50% cytotoxicity concentrations (CC50) of ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol were all greater than 500 μg/mL, and so was that of K. gracilis leaf extract (data not shown). The results also demonstrated K. gracilis leaf extract as being less cytotoxic in comparison with the 3 marker components.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity of K. gracilis leaf extract. RD cells were cultured overnight on 96-well plates. Serial dilutions of K. gracilis leaf extract were added and incubated for 24 and 48 hours, followed by MTT assay. Survival rates of cells were calculated as the ratio of optical density at 570–630 nm (OD570–630) of treated cells to OD570–630 of untreated cells. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe's test.

3.3. Inhibitory Effect of K. gracilis Leaf Extract on the Replication of EV71 and CVA16

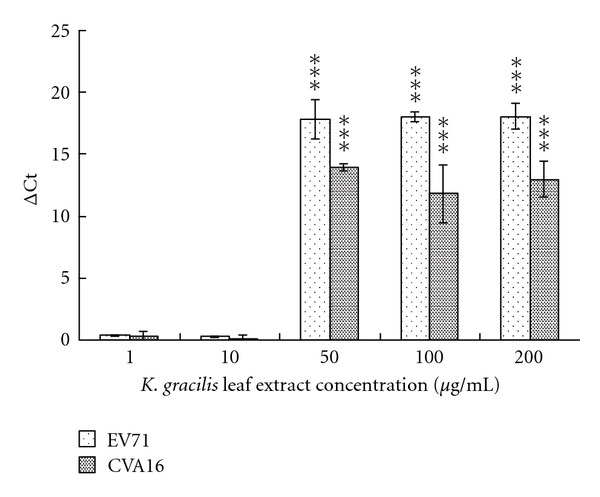

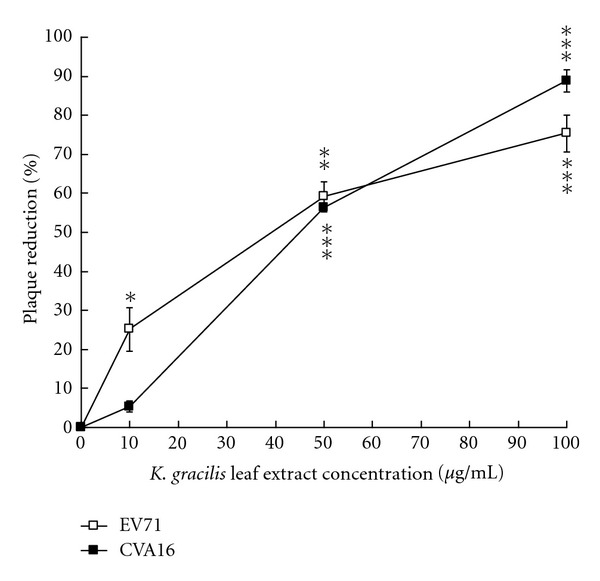

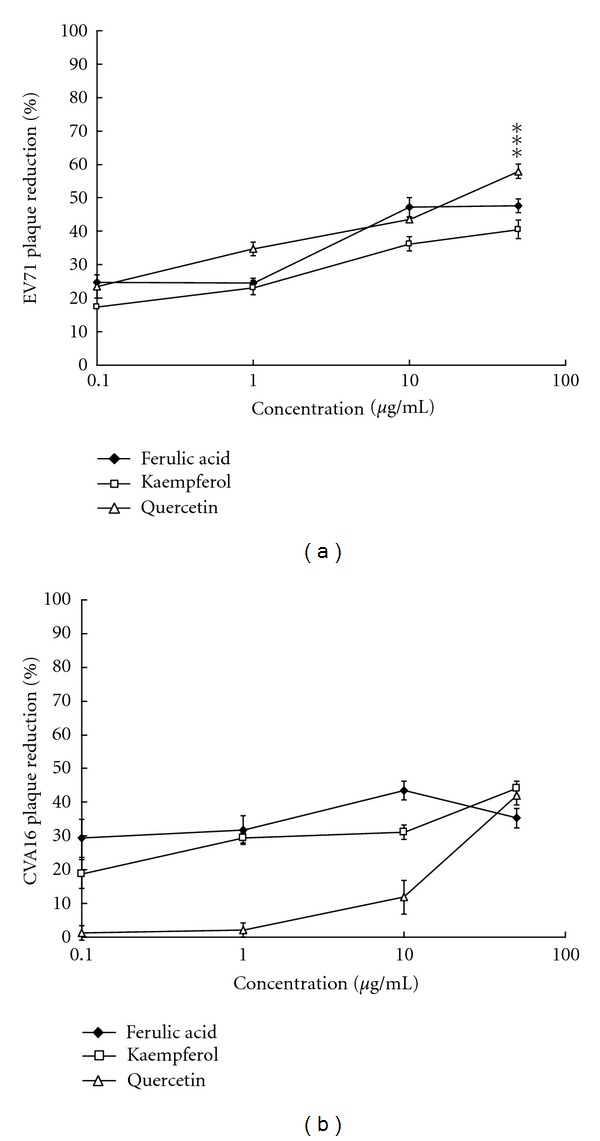

The anti-viral effects of K. gracilis leaf extract against EV71 and CVA16 were further evaluated in virucidal activity, cytopathic effect (CPE) reduction, viral plaque reduction, and virus yield reduction assays (see supplemental Figure 1 in Supplementary Material available online at doi:10.1155/2012/503165, Figures 3 and 4). In vitro incubation with 100 μg/mL of K. gracilis leaf extract for 30 min at room temperature had no significant effect on EV71 or CVA16 infectivity, indicating K. gracilis leaf extract had no virucidal activity against EV71 and CVA16 (data not shown). However, when K. gracilis leaf extract was added to EV71- and CVA16-infected RD cells, significant inhibition on EV71- and CVA16-induced CPE was observed, as shown in Supplemental Figures 1(a) and 1(b). For detection of virus yields in RD cells, the culture supernatants of EV71- and CVA16-infected RD cells with and without simultaneous-treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract in the concentration range of 1–200 μg/mL were harvested on day 2 and analyzed for viral RNA loads, using quantitative real-time RT-PCR (Figure 3). Real-time RT-PCR assay indicated that viral RNA loads in the supernatant of infected cells treated with 50 μg/mL of K. gracilis leaf extract (a Ct value of 31.68 for EV71 and a Ct value of 28.20 for CVA16) were significantly lower than those of infected cells without K. gracilis leaf extract treatment (a Ct value of 13.82 for EV71 and a Ct value of 14.25 for CVA16) (Figure 3). Moreover, treatment with K. gracilis leaf extract at 50 μg/mL had more than 1-log reduction in virus RNA loads since its delta Ct value was greater than 3.3. In addition, K. gracilis leaf extract exhibited concentration-dependent inhibitory effects on the replication of EV71 and CVA16 using plaque assay (Figure 4). IC50 value of K. gracilis leaf extract in plaque reduction assay was 35.88 μg/mL for EV71 and 42.91 μg/mL for CVA16. Moreover, quercetin, but not ferulic acid and kaempferol, showed a concentration-dependent manner on plaque reduction (IC50 = 39.63 μg/mL for EV71; IC50 = 59.53 μg/mL for CVA16) (Figure 5). The therapeutic index (TI) of K. gracilis leaf extract was greater than 10 against EV71 and CVA16, while quercetin TI was less than 10 against CVA16. K. gracilis leaf extract demonstrated higher antiviral potential than its marker component quercetin in treatment of EV71 and CVA16 infections.

Figure 3.

Reduction of virus yields by K. gracilis leaf extract. Each virus at the titer of 300 pfu was mixed with K. gracilis leaf extract and then added into RD cell cultures. Virus titers in each cultured supernatant were measured 48 h after infection using real-time RT-PCR. The delta Ct value was calculated by subtracting the Ct value for viral load in cultured media of K. gracilis leaf-extract-treated infected cells from the Ct value for viral load in cultured media of infected cells without treatment. Assay was performed as described in the Section 2. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe test.

Figure 4.

Plaque reduction of K. gracilis leaf extract. RD cells were infected with EV71 or CVA16 at a titer of 100 pfu and simultaneously treated with K. gracilis leaf extract at concentrations of 0, 10, 50, and 100 μg/mL. After 1 h incubation, RD cells were covered with agarose overlay medium and incubated for 2 days at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Finally, the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe test.

Figure 5.

Plaque reduction of quercetin, ferulic acid and kaempferol. RD cells were infected with EV71 (a) or CVA16 (b) at a titer of 100 pfu and simultaneously treated with quercetin, ferulic acid, and kaempferol at concentrations of 0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 50 μg/mL. After 1 h incubation, RD cells were covered with agarose overlay medium and incubated for 2 days at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Finally, the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe test.

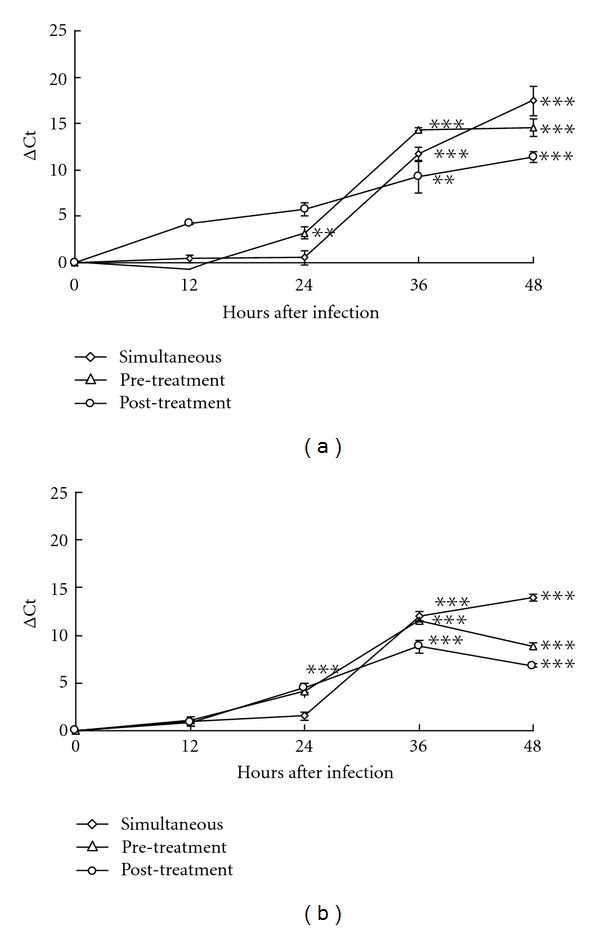

3.4. Antiviral Effect in Different Stages of EV71 and CVA16 Infections

To examine the possible mechanisms of K. gracilis leaf extract against EV71 and CVA16, the antiviral activity of K. gracilis leaf extract was further determined using time of addition studies (Figure 6). RD cells were treated with 50 μg/mL of K. gracilis leaf extract 30 min before, during, and 30 min after infection. Viral RNA quantitative real-time PCR demonstrated that K. gracilis leaf extract reached 90% yield reduction of EV71 at 12 h by the post-treatment procedure and at 36 h by the pre-treatment and simultaneous treatment procedures (Figure 6(a)). In addition, pre- and post-treatments of K. gracilis leaf extract both exerted 90% reductions in the yield of CVA16 at 24 h, and simultaneous-treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract achieved 90% reduction at 36 h (Figure 6(b)). The results showed antiviral effects of K. gracilis leaf extract on EV71 and CVA16 replications, being possibly associated with targeting viral protein function, reducing virus-induced cytopathogenesis, or inducing host antiviral responses.

Figure 6.

Time of addition assay for analysis of inhibitory effects of K. gracilis leaf extract on viral replication processes. K. gracilis leaf extracts at concentrations of 0 and 50 μg/mL were added to RD cells before (pre-treatment), during (simultaneous treatment), and after (post-treatment) infection with EV71 (a) or CVA16 (b) at the titer of 300 pfu. Virus titer in each cultured supernatant was measured 48 h after infection using real-time RT-PCR. Assay was performed as described in Section 2. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe's test.

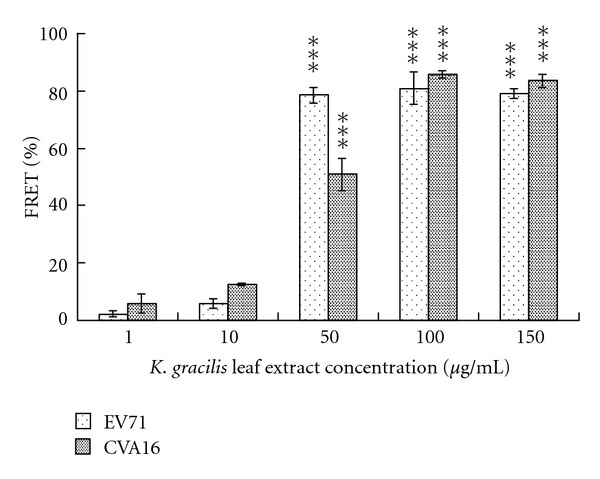

3.5. Inhibition of Viral 2A Protease Activity in Cell-Based FRET by K. gracilis Leaf Extract

Since enterovirus 2A protease that cleaves viral polyproteins and cellular factors has multifaceted activities for regulating different viral and cellular processes including viral replication and cytopathogenesis, particular in apoptosis and innate immunity [31], the possible inhibitory mechanisms of K. gracilis leaf extract on viral 2A protease was tested using a cell-based FRET assay of viral 2A protease activity. In general, a stable cell line continuously expressing GFP2-DsRed2 fusion protein connected by 2A protease cleavage site was used (HeLa-G2AwtR cells; GRTTLSTR↓GPPRGGPG; ↓ indicates cleavage site). The fusion protein would be cleaved by viral 2A protease at time of infection. To test FRET efficiency, HeLa-G2AwtR cells were infected with EV71 or CVA16 at MOIs of 0.25, 0.5, and 1 for 48 h and were harvested and subjected to measurement by a fluorescent-plate reader. The FRET ratio was defined as the intensity of emission at 590/14 nm for DsRed2 divided by that of GFP2 at 510/10 nm. Compared with the mock infection control, infected HeLa-G2AwtR cells exhibited a decline in percentage of the emission intensity of FRET probes in a virus titer-dependent manner (data not shown).

To further evaluate the inhibitory effects of K. gracilis leaf extract on the emission intensity of FRET probes in infected cells, HeLa-G2AwtR cells were infected with EV71 or CVA16 at MOI = 1 for 48 h. After 60 min of adsorption, the inoculum was aspirated and 200 μL of medium (modified Eagle's medium containing 2% FBS) alone or medium with K. gracilis leaf extract at various concentrations was added to each well (Figure 7). As shown in Figure 7, K. gracilis leaf extract increased the emission intensity of FRET probes in cells infected with EV71 and CVA16, exhibiting inhibitory effect on enteroviral 2A protease activity in a dose-dependent manner. IC50 values of K. gracilis leaf extract in cell-based FRET assay were 40.82 μg/mL for EV71 and 47.84 μg/mL for CVA16. The result implied K. gracilis leaf extract inhibited the proteolytic activity of EV71 and CVA16 2A proteases.

Figure 7.

Cell-based FRET assays for characterization of inhibitory effects of K. gracilis leaf extract on virus 2A protease enzymatic activity. HeLa-G2AwtR cells were infected with EV71 or CVA16 at a MOI of 1, and the cells were washed with MEM and then treated with K. gracilis leaf extract at the dosages of 1, 10, 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL. 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after infection, cells were harvested and subjected to measurement by a fluorescent-plate reader with the excitation wavelength at 390/20 nm and emission wavelength at 510/10 nm (for GFP2) or 590/14 nm (for DsRed2). FRET ratio was defined as intensity of emission at 590/14 nm divided by that at 510/10 nm. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe test.

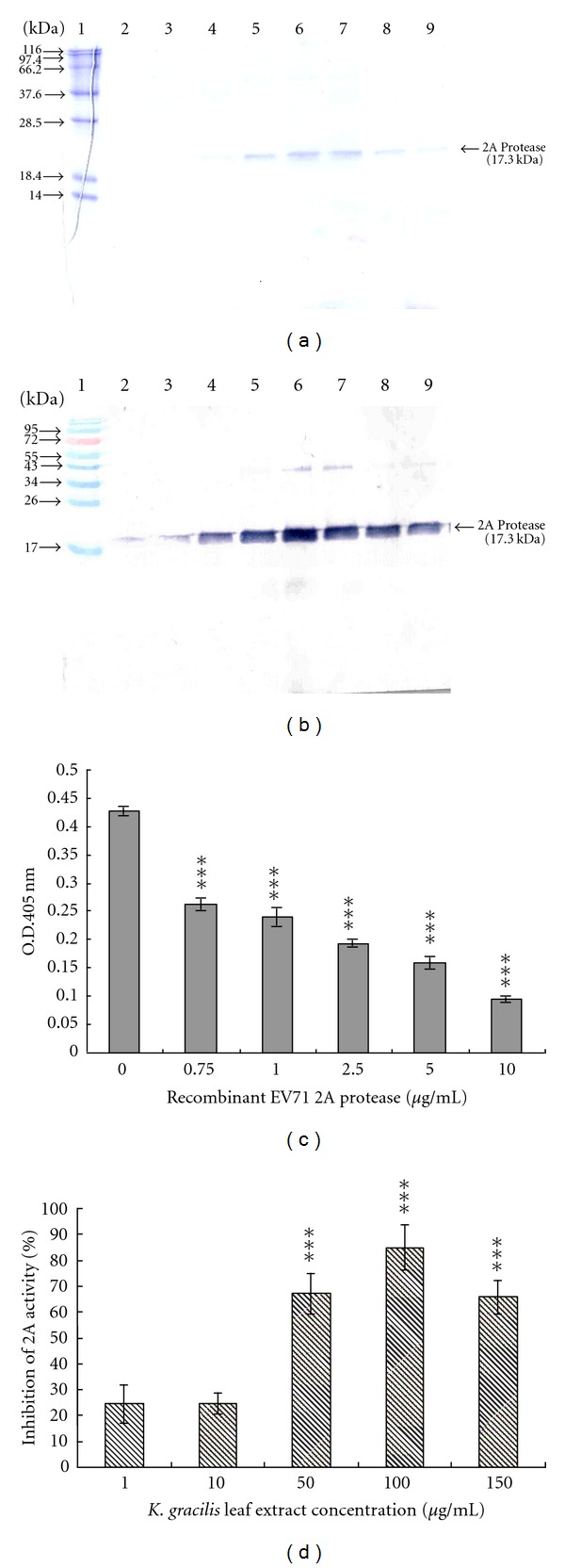

3.6. Inhibition of In Vitro 2A Protease Activity by K. gracilis Leaf Extract

To confirm the inhibitory effect of K. gracilis leaf extract on viral 2A protease, in vitro cleavage assay of recombinant 2A protease was performed using horseradish peroxidase-based substrate. The cDNA fragment of EV71 2A protease gene was cloned into pET24a expression vector and in-frame-fused with a C-terminal hexa-His-tag. EV71 2A protease protein was expressed in the recombinant E. coli cells after IPTG induction and purified using immobilized-metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) (Figure 8(a)). Western blot analysis of purified recombinant 2A protein with anti-His-tag antibody revealed an immunoreactive band near 17.3 kDa, matching closely to the expected molecular weight (Figure 8(b)). Recombinant 2A proteases of various concentrations (0.75, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL) were each added and incubated with HRP. The uncleaved HRP in each reaction was then incubated with ABTS/H2O2 and the remaining HRP activity measured at OD405. As shown, OD405 exhibited a reverse dose-dependent relationship with the increase of 2A protease (Figure 8(c)). IC50 value of K. gracilis leaf extract in 2A protease assay was 32.46 μg/mL for EV71. Moreover, this in vitro cleavage assay of recombinant 2A protease using HRP-based enzymatic method demonstrated K. gracilis leaf extract processed a specific inhibition of 2A protease.

Figure 8.

In vitro recombinant 2A protease enzymatic assay. SDS-PAGE (a) and Western blot analysis (b) of the purified 2A protease. Recombinant 2A protease protein was expressed after induction of IPTG treatment and purified through fusion His-tag bound to Ni-NTA agarose column. Purified recombinant 2A protease proteins were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose paper. The blot was probed with anti-His-tag and developed with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody and NBT/BCIP substrates. Lane 1 represents protein molecular weight markers. Lanes 2–9 show the fractions of the purified 2A protease proteins. For characterization of recombinant 2A protease activity in vitro (c), purified 2A protease at concentrations of 0, 0.75, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 μg/mL were incubated with HRP (0.5 μg/mL concentration) for 2 h at 37°C. Mixtures were developed with ABTS/H2O2 and measured at OD405. For inhibitory enzymatic assays (d), K. gracilis leaf extract at concentration of 1, 10, 50, 100, or 150 μg/mL was added into the mixture of purified 2A protease and HRP then incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 96-well plates in vitro. Mixtures were developed with ABTS/H2O2 and measured at OD405. Percentage of inhibition of 2A protease activity was calculated as (OD405HRP + drug + 2A protease − OD405HRP + 2A protease)/(OD405HRP only − OD405HRP + 2A protease) × 100%. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe's test.

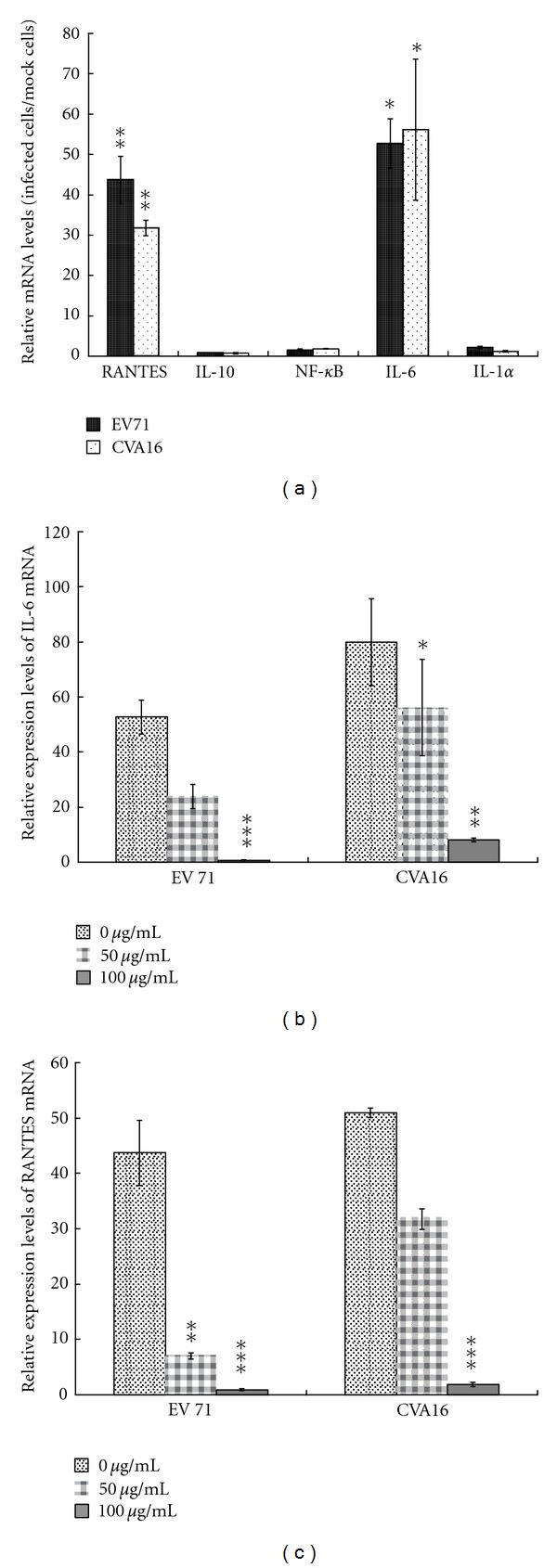

3.7. Inhibition of Virus-Induced Apoptosis and Proinflammatory Gene Expression by K. gracilis Leaf Extract

Since 2A protease was associated with EV71-induced apoptosis [32], Western blotting analysis of EV71-infected cells with or without the treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract was performed using anti-caspase 9 antibodies (Supplemental Figure 3). K. gracilis leaf extract significantly reduced the proform and active form of caspase 9 in EV71-infected cells, indicating that the inhibitory effect of K. gracilis leaf extract on 2A protease correlated with the decrease of EV71-induced apoptosis. Moreover, 2A protease interferes nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking of NF-κB via the cleavage of FG nucleoporins [31]; the present study further examined whether K. gracilis leaf extract inhibited virus-induced inflammatory gene expression and induced signal pathways by quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot assay (Figure 9 and Supplemental Figure 2). Both EV71 and CVA16 caused significant increases in IL-6 and RANTES mRNA levels; on the other hand, IL-10, NF-κB p65 and IL-1α were not elevated in RD cells 8 h after infection (Figure 9(a)). Treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract showed concentration-dependent inhibitions of EV71- and CVA16-induced IL-6 and RANTES expressions (Figures 9(b) and 9(c)), indicating significant inhibitory effect on EV71- and CVA16-induced inflammations. Subsequently, phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, and NF-κB p65 in virus-infected RD cells with or without treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract was analyzed by Western blotting with phosphorylation site-specific antibodies (Supplemental Figure 2). EV71 and CVA16 infections caused time-dependent increases of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, and NF-κB p65 phosphorylation. Treatment with K. gracilis leaf extract in infected cells inhibited NF-κB p65 phosphorylation 4 h after infection. Results demonstrated that inhibition of EV71- and CVA16-induced IL-6 and RANTES expressions correlated with the reduction of NF-κB p65 activation in RD cells and suggested that the antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory effect of K. gracilis leaf extract was involved in its antiviral activity against EV71 and CVA16.

Figure 9.

Relative levels of pro-inflammatory gene expression in infected RD cells with or without the treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract. For detection of virus-induced proinflammatory gene expression (a), RD cells were infected with EV71 or CVA16 for 8 h then harvested for RNA extraction. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described in Section 2. For detection of inhibitory effect of K. gracilis leaf extract on virus-induced proinflammatory gene expression, EV71- or CVA16-infected cells (b, c) were simultaneously treated with K. gracilis leaf extract at concentrations of 0, 50, and 100 μg/mL. After 8 h of incubation, total RNA was isolated from each group and Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described in Section 2. *P value < 0.05; **P value < 0.01; ***P value < 0.001 by Scheffe's test.

3.8. In Vivo Antiviral Activity by K. gracilis Leaf Extract

To evaluate in vivo antiviral activities of K. gracilis leaf extract, viral loads were examined in intestine samples from EV71-inoculated suckling mice with or without treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract (Supplemental Table 1). In a suckling mouse model, EV71 were detectable in intestine samples on days 2, 4, and 6 after intraperitoneal inoculation. Effect of treatment with K. gracilis leaf extract in EV71 EV71-inoculated suckling mice demonstrated an undetectable virus load in intestine samples on day 2 by one intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg of K. gracilis leaf extract and on day 6 by three intraperitoneal injections of 1 mg/kg of K. gracilis leaf extract. Results revealed in vivo antiviral activity of K. gracilis leaf extract as well as a concentration-dependent manner on inhibiting EV71 replication in the intestine of suckling mice.

4. Discussion

K. gracilis is a traditional Chinese medicinal herb commonly used for the treatments of injury, pain, and inflammation; such effects have also been evidenced in animal experiments of formalin-induced nociception and λ-carrageenan-induced inflammation recently [2]. This study demonstrated K. gracilis leaf extract exhibiting the antiviral activity against EV71 and CVA16 in vitro and in vivo (Figures 3–8, Supplemental Table 1). The results indicated K. gracilis exhibiting antiviral effects similar to other species in the Kalanchoe genus. For example, K. pinnata Pers. has been shown with significant antiviral activity against Herpes Simplex and Epstein-Barr viruses [16]. K. farinacea inhibits in vitro replication of Influenza A and Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 [15]. K. brasiliensis possesses anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects on zymosan-induced inflammation in mice [33]. Extracts of Kalanchoe farinacea have in vitro antiviral activity against Influenza A and Herpes Simplex Type 1 [15]. Together with the results and the previous reports, herb species in the Kalanchoe genus could possess active antiviral compounds.

HPLC and UV/vis absorption spectra demonstrated the chemical contents and the fingerprint profile of K. gracilis leaf extract of ethyl acetate layer by using a photodiode array detector (Figure 1). The relative amounts of ferulic acid (~7.59% w/w), quercetin (~0.33% w/w), and kaempferol (~0.16% w/w) were also identified in K. gracilis leaf extract of ethyl acetate layer and were found to be in agreement with identified flavonoids of K. gracilis in previous reports [3–5]. Flavonoids exhibit multiple functions, of which inhibition on viral replication [11–14] is among. In the present study, quercetin was demonstrated to possess concentration-dependent antienteroviral activities with the IC50 values of 39.63 μg/mL for EV71 and 59.53 μg/mL for CVA16 (Figure 5). However, anti-enteroviral activity of quercetin was less effective than that of K. gracilis leaf extract (Figure 4). K. gracilis leaf extract is suggested to contain other potent anti-enteroviral components besides quercetin. Phytochemically, Kalanchoe species are known to contain flavonoids (e.g., teolin, quercetin, quercitrin, kaempferol, eupafolin), glycosidic derivatives of eupafolin, bufadienolides, and coumarins [4, 5, 16], of which bis- and tetra-coumarins have been shown with inhibitory effects on the activity of HIV-1 integrase [7], while bufadienolides can reduce the activation of Epstein-Barr virus early antigen [16]. In addition, many active compounds of natural products have been identified as potential anti-EV71 agents, including gallic acid (IC50 = 0.8 μg/mL) [34], allophycocyanin (IC50 = 0.056 μM) [35], chrysosplenetin (IC50 = 0.2 μM), penduletin (IC50 = 0.2 μM) [36], and aloe-emodin (IC50 = 0.14 μM) [37]. This study revealed that quercetin showed a specific anti-EV71 activity (IC50 = 39.6 μg/mL), but might be less potent than the active compounds of natural products in above previous reports. Therefore, active phytochemical contents of K. gracilis leaf extract against EV71 and CVA16 should be further characterized.

In the evaluation of cytotoxicity of K. gracilis leaf extract, it was shown that it manifested less cytotoxicity in comparison with ferulic acid, quercetin, and kaempferol. Not only that, it showed better antiviral activities against EV71 and CVA16 as compared to the three marker components (Figures 2–4, Supplemental Figure 1). K. gracilis leaf extract at the concentration of 50 μg/mL potently inhibited 90% yield production of both viruses in RD cells (Figure 3). Also, IC50 value of K. gracilis leaf extract against EV71 and CVA16 were 35.88 μg/mL and 42.91 μg/mL, respectively (Figure 4), while the therapeutic index of K. gracilis leaf extract against EV71 and CVA16 ranged from 23 to 28. A literature survey indicated some extracts of Chinese herbs exhibiting anti-EV71 activities in vitro, such as Houttuynia cordata Thunb (IC50 = 125.9 μg/mL) [38], Woodfordia fruticosa Kurz (IC50 = 1.2 μg/mL) [34], Salvia miltiorrhiza (IC50 = 585 μg/mL) [39], Pueraria lobata (IC50 = 0.028 μg/mL) [40], and Glycyrrhiza uralensis (IC50 = 0.056 μg/mL) [41]. Therefore, K. gracilis leaf extract exhibited moderately potent anti- EV71 and CVA16 activities.

Although pre- and post-treatments of K. gracilis leaf extract exhibited time differences, the two treatments reached 90% viral reductions (Figure 6), implying that antiviral activity of K. gracilis leaf extract could be associated with targeting viral proteolytic enzymes, viral RNA replication machinery, and host cell factors, and even reducing virus-induced cytopathogenesis, or inducing host antiviral responses. Because enterovirus 2A protease cleaves viral polyproteins and cellular factors in which regulates in apoptosis and nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking of NF-κB [31, 32], viral 2A protease was selected as the possible target by K. gracilis leaf extract. In vitro recombinant 2A protease and cell-based FRET assays indicated K. gracilis leaf extract inhibited the enzymatic activity of viral 2A proteases in a concentration-dependent manner (Figures 7 and 8). In addition, K. gracilis leaf extract significantly reduced the EV71-induced apoptosis, such as decreasing proform and active form of caspase 9 in EV71-infected cells (Supplemental Figure 3). Likewise, K. gracilis leaf extract abated the up-regulation of IL-6 and RANTES gene expressions due to EV71 and/or CVA16 infection (Figure 9) which correlated with down-regulation of virus-induced NF-κB-mediated signaling (Supplemental Figure 2). Therefore, K. gracilis leaf extract exhibited an inhibitory effect on enteroviral 2A protease. This action might be in agreement with the decrease of virus-induced apoptosis and NF-κB-mediated proinflammation. Our future perspective would be to purify and identify potent K. gracili compounds as viral 2A inhibitors.

It has been shown that significant increases in the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, IFN-γ, and TNF-α are detected in the serum and cerebral spinal fluid of EV71-infected patients [23, 42–45]. Moreover, elevation of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in CSF strongly correlates with clinical severity and is believed to be responsible for EV71-induced immunopathogenesis [26, 44, 46]. Clinically, treatment of anti-IL-6 neutralizing antibodies increases survival rates, reduces tissue damage, and activates immune cells, but could not affect the viral loads in EV71-infected neonate mice [47]. We demonstrated K. gracilis leaf extract concentration dependently reduced IL-6 mRNA levels upregulated by EV71 or CVA16 infection in RD cells (Figures 9(a)–9(c)). Moreover, we suggested significant inhibitory effects of K. gracilis leaf extract on in vitro replications of EV71 and CVA16 (Supplemental Figure 1, Figures 4–6) associated with its potent inhibition on viral 2A protease activities (Figures 7 and 8). Therefore, a combination of effective compounds of K. gracilis leaf extract shows a potential therapeutic approach against enteroviral infection.

In conclusion, K. gracilis leaf extract contains effective compounds with anti-enteroviral activities. K. gracilis leaf extract possesses potent effects in inhibiting enzymatic activities of viral 2A protease and reducing virus-induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and RANTES. K. gracilis leaf extract could be a safe and potential therapeutic agent against enteroviral infection.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Reduction of cytopathic effects by K. gracilis leaf extract. The morphology of RD cells infected with EV71 (A) or CVA16 (B) were observed for the effect of K. gracilis leaf extract in CPE reduction assay. EV71 and CVA16 at the MOI of 1 was each mixed with K. gracilis leaf extract, and then added into RD cell cultures. Incubated RD cells were observed and photographed under microscopy 24- and 48-h post infection.

Supplemental Figure 2: Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2 and NF-κB p65 in infected RD cells with or without the treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract. RD cells were infected with EV71 (A) or CVA16 (B) and simultaneously treated with K. racilis leaf extract at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. The cells were harvested at 0-, 30-, 60- and 240 min post infection, and Western blotting analysis was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Supplemental Figure 3: Western blotting of caspase 9 in EV71-infected RD cells with or without the treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract. RD cells were infected with EV71 at a MOI of 1 in the absence (Lane 1) and presence of K. racilis leaf extract at concentrations of 10, 50 and 100 μg/ml (Lanes 2-4). The cells were harvested 1 day post infection, and Western blotting analysis was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Supplemental Table 1: Virus loads in pooled intestines from EV71-inoculated suckling mice with or without treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by Grants from China Medical University (CMU99-NSC-08, CMU99-S-23, CMU98-P-03-M, CMU100-S-33) and the Republic of China National Science Council (NSC97–2320-B-039-023-MY3, NSC99–2628-B-039-006-MY3).

References

- 1.Kao MC. Handbook of Taiwan Medicinal Plants. Taipei, Taiwan: Southern Materials Center; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai ZR, Peng WH, Ho YL, et al. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of the methanol extract of Kalanchoe gracilis (L.) DC stem in mice. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2010;38(3):529–546. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X10008032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai ZR, Ho YL, Hung SC, et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative activities of Kalanchoe gracilis (L.) DC stem. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2011;39(6):1275–1290. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X1100955X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin CSL, Yang SL, Roberts MF, Phillipson JD. Eupafolin rhamnosides from Kalanchoe gracilis . Journal of Natural Products. 1989;52(5):970–974. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu PL, Hsu YL, Wu TS, Bastow KF, Lee KH. Kalanchosides A-C, new cytotoxic bufadienolides from the aerial parts of Kalanchoe gracilis . Organic Letters. 2006;8(23):5207–5210. doi: 10.1021/ol061873m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwu JR, Singha R, Hong SC, et al. Synthesis of new benzimidazole-coumarin conjugates as anti-hepatitis C virus agents. Antiviral Research. 2008;77(2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang CC, Mouscadet JF, Tsai HJ, Liu CT, Hsu LY. Synthesis and HIV-1 integrase inhibition of novel bis- or tetra-coumarin analogues. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2007;55(12):1740–1743. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu M, Cong XJ, Li P, Tan JJ, Chen WZ, Wang CX. Study on the inhibitory mechanism and binding mode of the hydroxycoumarin compound NSC158393 to HIV-1 integraseby molecular modeling. Biopolymers. 2009;91(9):700–709. doi: 10.1002/bip.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwu JR, Lin SY, Tsay SC, De Clercq E, Leyssen P, Neyts J. Coumarin-purine ribofuranoside conjugates as new agents against hepatitis c virus. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;54(7):2114–2126. doi: 10.1021/jm101337v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong EBB, Watanabe N, Saito A, et al. Vipirinin, a coumarin-based HIV-1 Vpr inhibitor, interacts with a hydrophobic region of Vpr. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(16):14049–14056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conti C, Tomao P, Genovese D, Desideri N, Stein ML, Orsi N. Mechanism of action of the antirhinovirus flavanoid 4′,6-dicyanoflavan. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1992;36(1):95–99. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conti C, Genovese D, Santoro R, Stein ML, Orsi N, Fiore L. Activities and mechanisms of action of halogen-substituted flavanoids against poliovirus type 2 infection in vitro. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1990;34(3):460–466. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.3.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genovese D, Conti C, Tomao P, et al. Effect of chloro-, cyano-, and amidino-substituted flavanoids on enterovirus infection in vitro. Antiviral Research. 1995;27(1-2):123–136. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvati AL, De Dominicis A, Tait S, Canitano A, Lahm A, Fiore L. Mechanism of action at the molecular level of the antiviral drug 3(2H)-isoflavene against type 2 poliovirus. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48(6):2233–2243. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2233-2243.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mothana RA, Mentel R, Reiss C, Lindequist U. Phytochemical screening and antiviral activity of some medicinal plants from the island Soqotra. Phytotherapy Research. 2006;20(4):298–302. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Supratman U, Fujita T, Akiyama K, et al. Anti-tumor promoting activity of bufadienolides from Kalanchoe pinnata and K. Daigremontiana × tubiflora. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2001;65(4):947–949. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knipe DN, Howley PM, Griffin DE, et al. Enteroviruses: Polioviruses, Coxsackieviruses, Echoviruses, and Newer Enteroviruses. Fields Virology. (5th edition) 2007;1 Edited by Pallansch M. A. and Roos R. P. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S, Chow VT, Phoon MC, Chan KP, Poh CL. Direct detection of enterovirus 71 (EV71) in clinical specimens from a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Singapore by reverse transcription-PCR with universal enterovirus and EV71-specific primers. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002;40(8):2823–2827. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2823-2827.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng H, Wen F, Gan Y, Huang W. MRI and associated clinical characteristics of EV71-induced brainstem encephalitis in children with hand-foot-mouth disease. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0979-3. Neuroradiology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders SA, Herrero LJ, McPhie K, et al. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71 over two decades in an Australian urban community. Archives of Virology. 2006;151(5):1003–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin KH, Hwang KP, Ke GM, et al. Evolution of EV71 genogroup in Taiwan from 1998 to 2005: an emerging of subgenogroup C4 of EV71. Journal of Medical Virology. 2006;78(2):254–262. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang B, Chuang H, Yang KD. Sialylated glycans as receptor and inhibitor of enterovirus 71 infection to DLD-1 intestinal cells. Virology Journal. 2009;6:141–146. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang LY, Lin TY, Hsu KH, et al. Clinical features and risk factors of pulmonary oedema after enterovirus-71-related hand, foot, and mouth disease. The Lancet. 1999;354(9191):1682–1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho M, Chen ER, Hsu KH, et al. An epidemic of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(13):929–935. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang CC, Liu CC, Chang YC, Chen CY, Wang ST, Yeh TF. Neurologic complications in children with enterovirus 71 infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(13):936–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin TY, Hsia SH, Huang YC, Wu CT, Chang LY. Proinflammatory cytokine reactions in enterovirus 71 infections of the central nervous system. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36(3):269–274. doi: 10.1086/345905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podin Y, Gias EL, Ong F, et al. Sentinel surveillance for human enterovirus 71 in Sarawak, Malaysia: lessons from the first 7 years. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:180–189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yen FB, Chang LY, Kao CL, et al. Coxsackieviruses infection in northern Taiwan—epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2009;42(1):38–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai MT, Cheng YH, Liu YN, Liao NC, Lu WW, Kung SH. Real-time monitoring of human enterovirus (HEV)-infected cells and anti-HEV 3C protease potency by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2009;53(2):748–755. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00841-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oberste MS, Peñaranda S, Rogers SL, Henderson E, Nix WA. Comparative evaluation of Taqman real-time PCR and semi-nested VP1 PCR for detection of enteroviruses in clinical specimens. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2010;49(1):73–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castelló A, Alvarez E, Carrasco L. The multifaceted poliovirus 2A protease: regulation of gene expression by picornavirus proteases. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2011;2011:23 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/369648. Article ID 369648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo RL, Kung SH, Hsu YY, Liu WT. Infection with enterovirus 71 or expression of its 24 protease induces apoptotic cell death. Journal of General Virology. 2002;83(6):1367–1376. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-6-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibrahim T, Cunha JM, Madi K, da Fonseca LM, Costa SS, Gonçalves Koatz KVL. Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of Kalanchoe brasiliensis . International Immunopharmacology. 2002;2(7):875–883. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi HJ, Song JH, Park KS, Baek SH. In vitro anti-enterovirus 71 activity of gallic acid from Woodfordia fruticosa flowers. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2010;50(4):438–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shih SR, Tsai KN, Li YS, Chueh CC, Chan EC. Inhibition of enterovirus 71-induced apoptosis by allophycocyanin isolated from a blue-green alga Spirulina platensis . Journal of Medical Virology. 2003;70(1):119–125. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu QC, Wang Y, Liu YP, et al. Inhibition of enterovirus 71 replication by chrysosplenetin and penduletin. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;44(3):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin CW, Wu CF, Hsiao NW, et al. Aloe-emodin is an interferon-inducing agent with antiviral activity against Japanese encephalitis virus and enterovirus 71. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2008;32(4):355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin TY, Liu YC, Jheng JR, et al. Anti-enterovirus 71 activity screening of Chinese herbs with anti-infection and inflammation activities. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2009;37(1):143–158. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X09006734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu BW, Pan TL, Leu YL, et al. Antiviral effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen) against enterovirus 71. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2007;35(1):153–168. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X07004709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su FM, Chang JS, Wang KC, Tsai JJ, Chiang LC. A water extract of Pueraria lobata inhibited cytotoxicity of enterovirus 71 in a human foreskin fibroblast cell line. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2008;24(10):523–530. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo KK, Chang JS, Wang KC, Chiang LC. Water extract of Glycyrrhiza uralensis inhibited enterovirus 71 in a human foreskin fibroblast cell line. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2009;37(2):383–394. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X09006904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang LY, Huang YC, Lin TY. Fulminant neurogenic pulmonary oedema with hand, foot, and mouth disease. The Lancet. 1998;352(9125):367–368. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)24031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang SM, Lei HY, Huang KJ, et al. Pathogenesis of enterovirus 71 brainstem encephalitis in pediatric patients: roles of cytokines and cellular immune activation in patients with pulmonary edema. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2003;188(4):564–570. doi: 10.1086/376998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang SM, Lei HY, Su LY, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid cytokines in enterovirus 71 brain stem encephalitis and echovirus meningitis infections of varying severity. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2007;13(7):677–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin TY, Chang LY, Huang YC, Hsu KH, Chiu CH, Yang KD. Different proinflammatory reactions in fatal and non-fatal enterovirus 71 infections: implications for early recognition and therapy. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91(6):632–635. doi: 10.1080/080352502760069016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weng KF, Chen LL, Huang PN, Shih SR. Neural pathogenesis of enterovirus 71 infection. Microbes and Infection. 2010;12(7):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khong WX, Foo DG, Trasti SL, Tan EL, Alonso S. Sustained high levels of interleukin-6 contribute to the pathogenesis of enterovirus 71 in a neonate mouse model. Journal of Virology. 2011;85(7):3067–3076. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01779-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Reduction of cytopathic effects by K. gracilis leaf extract. The morphology of RD cells infected with EV71 (A) or CVA16 (B) were observed for the effect of K. gracilis leaf extract in CPE reduction assay. EV71 and CVA16 at the MOI of 1 was each mixed with K. gracilis leaf extract, and then added into RD cell cultures. Incubated RD cells were observed and photographed under microscopy 24- and 48-h post infection.

Supplemental Figure 2: Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, ERK1/2 and NF-κB p65 in infected RD cells with or without the treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract. RD cells were infected with EV71 (A) or CVA16 (B) and simultaneously treated with K. racilis leaf extract at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. The cells were harvested at 0-, 30-, 60- and 240 min post infection, and Western blotting analysis was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Supplemental Figure 3: Western blotting of caspase 9 in EV71-infected RD cells with or without the treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract. RD cells were infected with EV71 at a MOI of 1 in the absence (Lane 1) and presence of K. racilis leaf extract at concentrations of 10, 50 and 100 μg/ml (Lanes 2-4). The cells were harvested 1 day post infection, and Western blotting analysis was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Supplemental Table 1: Virus loads in pooled intestines from EV71-inoculated suckling mice with or without treatment of K. gracilis leaf extract.