Abstract

Background

Inhalation of diesel exhaust impairs vascular function in man, by a mechanism that has yet to be fully established. We hypothesised that pulmonary exposure to diesel exhaust particles (DEP) would cause endothelial dysfunction in rats as a consequence of pulmonary and systemic inflammation.

Methods

Wistar rats were exposed to DEP (0.5 mg) or saline vehicle by intratracheal instillation and hind-limb blood flow, blood pressure and heart rate were monitored in situ 6 or 24 h after exposure. Vascular function was tested by administration of the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine (ACh) and the endothelium-independent vasodilator sodium nitroprusside (SNP) in vivo and ex vivo in isolated rings of thoracic aorta, femoral and mesenteric artery from DEP exposed rats. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and blood plasma were collected to assess pulmonary (cell differentials, protein levels & interleukin-6 (IL-6)) and systemic (IL-6), tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and C-reactive protein (CRP)) inflammation, respectively.

Results

DEP instillation increased cell counts, total protein and IL-6 in BALF 6 h after exposure, while levels of IL-6 and TNFα were only raised in blood 24 h after DEP exposure. DEP had no effect on the increased hind-limb blood flow induced by ACh in vivo at 6 or 24 h. However, responses to SNP were impaired at both time points. In contrast, ex vivo responses to ACh and SNP were unaltered in arteries isolated from rats exposed to DEP.

Conclusions

Exposure of rats to DEP induces both pulmonary and systemic inflammation, but does not modify endothelium-dependent vasodilatation. Other mechanisms in vivo limit dilator responses to SNP and these require further investigation.

Keywords: Diesel, Pollution, Particle, Particulate, Blood vessel, Artery, Vasodilatation, Endothelium, Inflammation

Background and objectives

Exposure to air pollution has been associated with increased cardiovascular mortality and morbidity [1-3]. These associations are strongest for the particulate matter (PM) in air pollution, and the World Health Organisation has estimated that airborne particles are responsible for half a million premature deaths each year [4]. Ultrafine particles (or nanoparticles) are of specific concern because their small size allows them to penetrate deep into the respiratory tract [5] and also engenders them with a large reactive surface area. Exhaust from diesel engines is especially rich in nanoparticles and, therefore, may contribute greatly to the health effects of PM in urban environments [6,7].

The mechanism(s) by which inhaled PM alters cardiovascular function has not been established. We have shown that controlled exposure to diesel exhaust impairs endothelial vasomotor function in healthy volunteers [8-10] and in patients with stable coronary heart disease [11]. The vascular impairment observed appears to be mediated by the particulate component of the exhaust rather than the gaseous co-pollutants [7,10]. Furthermore, ex vivo exposure of blood vessels to diesel exhaust particles (DEP) inhibits nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilatation via generation of superoxide free radicals [12]. Thus, DEP can directly alter endothelial cell function but this assumes that a considerable number of the particles are able to translocate from the lung to the circulation. While studies have demonstrated that translocation of nanoparticles is feasible [13-15] there remains considerable uncertainty over whether this mechanism underlies the health effects of combustion-derived nanoparticles [16-18]. An alternative suggestion is that inflammation induced by PM in the lung may spill-over into the systemic circulation, causing indirect cardiovascular changes [19]. Several different types of particulate have been shown to induce pulmonary inflammation [18,20], but the occurrence and potential role of systemic inflammation following pulmonary exposure to particulates is often inconsistent [8,21,22]. We hypothesise that instillation of DEP will cause endothelial dysfunction in rats as a consequence of pulmonary and systemic inflammation. Analysis of arteries isolated from PM-exposed animals has generally shown little evidence of dysfunction. However, this may be due to limitations of ex vivo analyses, which remove the vessel from neurohumoural control in vivo. Therefore, we addressed our hypothesis by measuring arterial function both in vivo (in the hind-limb resistance bed) and ex vivo in isolated conduit (aorta, femoral) and resistance (mesenteric) arteries following intra-tracheal instillation of rats with DEP or vehicle (saline).

Results

Assessment of pulmonary inflammation

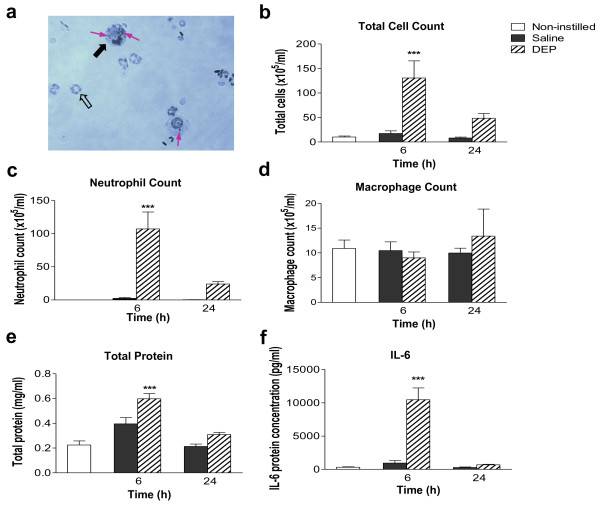

Instillation of DEP was associated with an influx of neutrophils and macrophages into bronchoaveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Black particles were evident within these cells following DEP instillation (Figure 1a). Instillation of saline produced no significant alteration in the total cell number in BALF compared with untreated control animals. However, instillation of DEP increased the number of cells in lavage 6 h and 24 h post-exposure (Figure 1b). Total cell counts were greatest 6 h post-exposure (130 ± 35 × 105/mL versus 17 ± 5 × 105/mL in saline controls, P < 0.001) and remained elevated at 24 h (49 ± 10 × 105 cells/mL versus 8.3 ± 1.8 × 105 cells/mL in saline-treated controls). The increase in the total cell count 6 h after DEP instillation was predominately due to increases in neutrophil number (Figure 1c). There were no differences in the number of macrophages in BALF between the treatment groups (Figure 1d) and, in all groups, eosinophil and lymphocyte numbers were below the threshold for detection. This pattern of cell differentials was identical when expressed as a percentage of total cell number (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Instillation of diesel exhaust particles (DEP) causes transient pulmonary inflammation. (a) Representative photomicrograph of a cytocentrifuge slide prepared from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collected from a DEP-instilled animal 6 h after instillation. Neutrophils (open arrow) and alveolar macrophages (black arrow) containing particulate (purple arrow) are apparent. Diff-Quick™ staining, ×400 magnification. BALF was analysed for (b) total cell count, (c) neutrophils, (d) alveolar macrophages, (e) total protein (bicinchonic acid assay) and (f) interleukin-6 (IL-6). Non-instilled (open columns), saline-instilled (solid columns) and DEP-instilled (hatched columns) animals 6 and 24 h after instillation. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4-8; data for non-instilled groups were pooled, n = 11) ***P < 0.001 DEP versus saline; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Protein concentration in the BALF was measured as a surrogate of lung permeability [23]. After saline-instillation, total protein concentration was similar to baseline levels at all time-points (Figure 1e). In contrast, total protein increased 2- to 3-fold 6 h after DEP instillation (P < 0.001, n = 6-8; Figure 1e), with levels returning to baseline by 24 h. Measurement of the cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) showed a similar pattern with levels increasing above baseline (0.30 ± 0.07 ng/ml) 6 h after DEP instillation (10.5 ± 1.8 ng/ml; P < 0.001) and returning to baseline within 24 h (Figure 1f). Levels of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were also measured in the BALF, but both were below the limits of detection (< 16 pg/ml for TNFα and < 39 pg/ml for CRP).

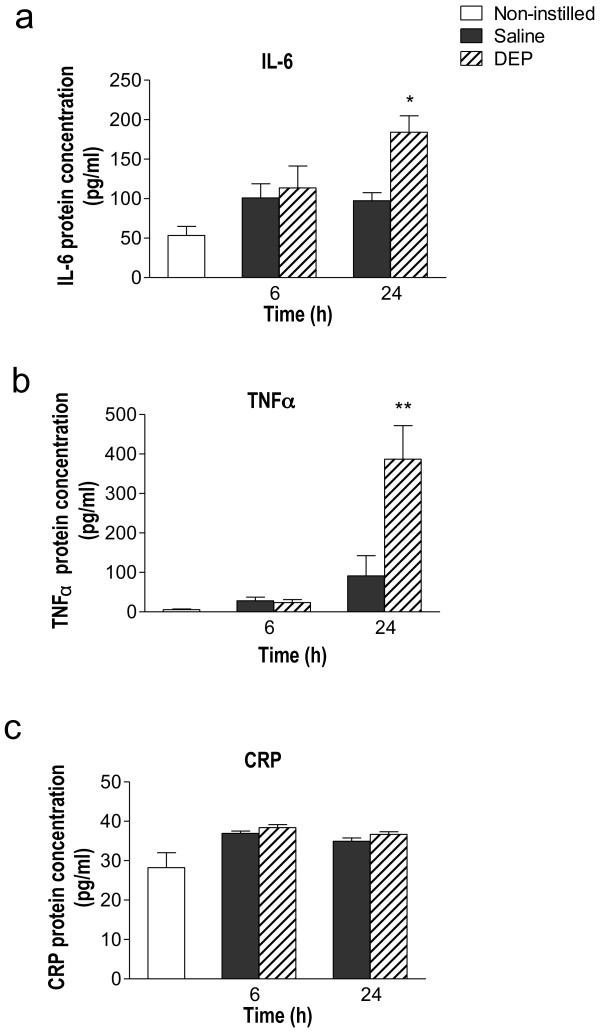

Assessment of inflammatory response in blood

Red blood cell and platelet counts were not different across treatment groups (Table 1). There was a significant increase in numbers of white blood cells at 6 h after instillation (P < 0.05), that decreased to levels that were not significantly different to those of the saline-treated group at 24 h (Table 1). Baseline plasma IL-6 and TNFα levels were 53.5 ± 11.5 pg/ml and 5.8 ± 1.5 pg/ml, respectively (Figure 2a &2b) and there was no significant change from baseline at 6 h after DEP or saline instillation. At 24 h after instillation, DEP induced significantly higher levels of both IL-6 (P < 0.05; Figure 2a) and TNFα (P < 0.01; Figure 2b) in comparison to the saline instilled group. Although intratracheal instillation of DEP elevated baseline levels of circulating CRP at both time points (Figure 2c), no statistical differences were observed between the saline and DEP groups.

Table 1.

Blood cell differentials 6 or 24 h after instillation of diesel exhaust particulate (DEP) or saline

| Treatment group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 h | 24 h | ||||

| Non-instilled | Saline | DEP | Saline | DEP | |

|

RBC (×103/pl) |

5.9 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.3 |

|

WBC (×103/μl) |

4.6 ± 0.5 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.3* | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 1.4 |

|

platelets (×103/μl) |

358 ± 93 | 415 ± 106 | 447 ± 49 | 525 ± 177 | 618 ± 164 |

Abbreviations: DEP, diesel exhaust particles; RBC = red blood cells; WBC, white blood cells.

Results are mean ± SEM (n = 5). Not significant (P > 0.05) unless otherwise stated. *P < 0.05, saline vs DEP, Bonferroni post-hoc test, following two-way ANOVA

Figure 2.

Instillation of diesel exhaust particles (DEP) causes systemic inflammation. Plasma cytokines (a) Interleukin-6 (IL-6) (b) Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) & (c) C-reactive protein (CRP) were detected by ELISA. Non-instilled (open columns), saline-instilled (solid column) or DEP-instilled (0.5 mg; hatched columns) animals 6 and 24 h after instillation. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4-6). , *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 DEP versus saline; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

In vivo vascular function

Baseline systolic blood pressure was significantly higher in DEP-, than in saline-, treated rats 6 h after exposure (P < 0.05; Table 2). Diastolic and mean arterial pressure showed the same trend, but this failed to reach statistical significance. Baseline heart rate and blood flow were not different between treatment groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline heart rate, arterial pressure and hind-limb blood flow 6 and 24 h after instillation of diesel exhaust particulate (DEP) or saline (assessed before vasodilator administration)

| Treatment group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 h | 24 h | ||||

| Non-instilled | Saline | DEP | Saline | DEP | |

|

HR (bpm) |

354 ± 6 | 352 ± 7 | 372 ± 11 | 335 ± 6 | 353 ± 7 |

|

SBP (mmHg) |

103.9 ± 5.7 | 105.1 ± 5.1 | 130.7 ± 13.4* | 101.3 ± 2.4 | 116.9 ± 5.9 |

|

DBP (mmHg) |

88.9 ± 6.5 | 98.7 ± 5.0 | 122.5 ± 12.8 | 85.3 ± 2.2 | 101.8 ± 7.1 |

|

MABP (mmHg) |

91.4 ± 7.4 | 100.9 ± 5.0 | 125.3 ± 13.0 | 91.2 ± 1.8 | 106.8 ± 6.5 |

|

HBF (ml/min) |

2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

DEP, Diesel Exhaust Particles; HR, heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; HBF, hind-limb blood flow.

Results are mean ± SEM (n = 5-8). Not significant (P > 0.05) unless otherwise stated. *P < 0.05, saline vs DEP, Bonferroni post-hoc test, following two-way ANOVA

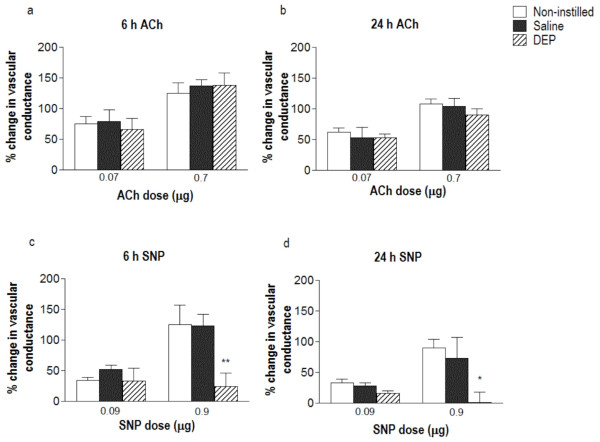

Intra-arterial injections of acetylcholine (ACh) into the hind-limb vascular bed increased femoral vascular conductance (FVC; Figure 3a &3b) without affecting mean arterial blood pressure. Neither saline nor DEP administration altered arteriolar dilations in response to ACh at either 6 h (Figure 3a) or 24 h (Figure 3b) after instillation. Intra-arterial administration of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was associated with a tendency for a transient reduction in mean arterial blood pressure (6-12 mmHg in both saline- and DEP- exposed rats) but this change in blood pressure was not statistically significant in any group (P > 0.10 for all). SNP (0.9 μg) produced approximately a 2-fold increase in vascular conductance above baseline in the non-instilled control animals and in saline-instilled animals at 6 h or 24 h after instillation (Figure 3c & Figure 3d). At both time points DEP significantly suppressed this increase in conductance evoked by SNP (Figure 3c &3d).

Figure 3.

Instillation of diesel exhaust particles (DEP) does not affect endothelium-dependent relaxation, but impairs vasodilator response to sodium nitroprusside, in vivo. Percent change in femoral vascular conductance (FVC) from baseline in response to intra-arterial acetylcholine (ACh; 0.07 & 0.7 μg) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 0.09 & 0.9 μg) 6 h (a &c) and 24 h (b &d) after instillation. Responses were obtained in non-instilled rats (open column), saline-instilled rats (solid column) or DEP-instilled rats (0.5 mg; hatched column). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4-6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 DEP versus saline; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Ex vivo vascular function

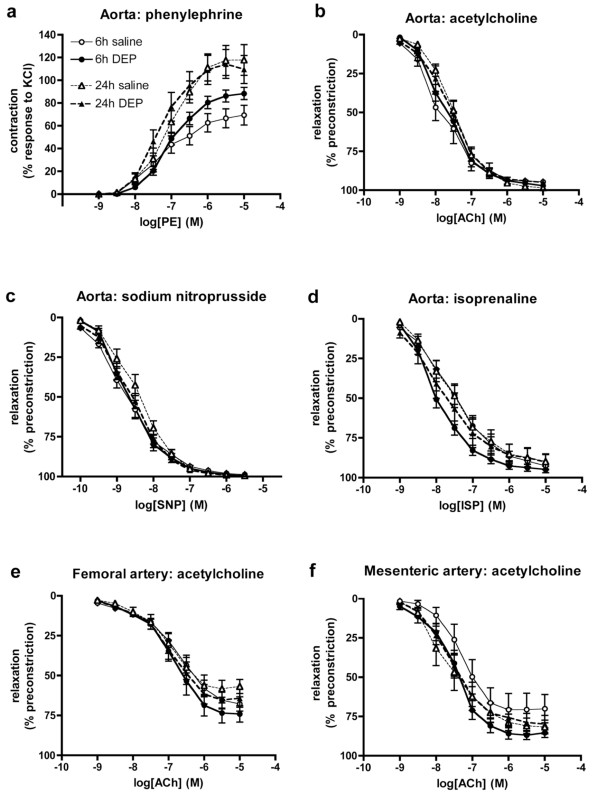

Responses to vasodilator drugs were assessed ex vivo in thoracic aortas from rats, 6 or 24 h after instillation (Figure 4, Table 3). DEP-instillation had no effect on the sensitivity of the contractile responses to phenylephrine in either the 6 h (P = 0.31) or 24 h groups (P = 0.82; Figure 4a), although there was a significantly greater maximum contraction to phenylephrine in the 6 h DEP group (P = 0.045; Table 3). Importantly, DEP had no influence on vasodilator responses to ACh (P = 0.68 for 6 h, P = 0.89 for 24 h; Figure 4b) or SNP (P = 0.79 for 6 h, P = 0.22 for 24 h; Figure 4c) at either time point. In an additional group of animals sacrificed 2 h after instillation, responses to ACh and SNP were identical in saline- and DEP-treated animals at this earlier time point (n = 6; data not shown). There was no significant difference between the concentration-response curves to isoprenaline, as a whole, in the aortas from saline- and DEP-treated animals (two-way ANOVA; P > 0.06; Figure 4d), although a small, but significant, difference in IC50 values was observed at 6 h (unpaired t-test; P = 0.013; Table 3).

Figure 4.

Instillation of diesel exhaust particles (DEP) has no effect on vascular responses ex vivo. (a) Contraction to phenylephrine (PE), and relaxation to (b) acetylcholine (ACh), (c) sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and (d) isoprenaline (ISP) in the thoracic aorta. Responses to ACh in (e) femoral artery and (f) 3rd order mesenteric arteries. Data from saline-instilled animals (open symbols) and DEP-instilled animals (closed symbols) sacrificed at 6 h (circles, solid line) or 24 h (triangles, dashed line) after instillation. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6-10). No significant differences were found between saline or DEP instilled animals at either time points for all vessels (two-way ANOVA).

Table 3.

Ex vivo contractile and relaxant responses in arterial rings isolated 6 and 24 h after instillation of rats with diesel exhaust particles (DEP) or saline

| phenylephrine | acetylcholine | sodium nitroprusside | isoprenaline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logEC50 | Max (% response to KCl) |

logIC50 | Imax (% preconstriction) |

logIC50 | Imax (% preconstriction) |

logIC50 | Imax (% preconstriction) |

|

| Aorta | ||||||||

| 6 h | ||||||||

| saline | -7.24 ± 0.14 | 67.1 ± 8.1 | -7.88 ± 0.20 | 94.9 ± 1.3 | -8.67 ± 0.13 | 96.7 ± 1.0 | -7.52 ± 0.15 | 90.0 ± 1.8 |

| DEP | -7.03 ± 0.07 | 88.6 ± 5.1* | -7.75 ± 0.11 | 96.1 ± 1.4 | -8.70 ± 0.11 | 87.9 ± 1.0 | -8.07 ± 0.10* | 93.1 ± 2.2 |

| 24 h | ||||||||

| saline | -7.29 ± 0.13 | 120.8 ± 14.5 | -7.52 ± 0.10 | 99.3 ± 0.5 | -8.43 ± 0.13 | 99.3 ± 0.6 | -7.62 ± 0.16 | 88.0 ± 5.8 |

| DEP | -7.38 ± 0.11 | 115.3 ± 13.0 | -7.67 ± 0.17 | 96.2 ± 1.5 | -8.60 ± 0.10 | 98.9 ± 0.4 | -7.62 ± 0.26 | 87.8 ± 6.4 |

| Femoral Artery | ||||||||

| 6 h | ||||||||

| saline | -5.59 ± 0.08 | 115.1 ± 24.2 | -6.69 ± 0.11 | 68.9 ± 4.9 | -7.80 ± 0.15 | 94.1 ± 2.9 | -6.39 ± 0.29 | 67.3 ± 7.1 |

| DEP | -5.53 ± 0.06 | 91.8 ± 4.0 | -6.81 ± 0.14 | 77.2 ± 5.6 | -7.81 ± 0.18 | 95.1 ± 1.9 | -6.51 ± 0.27 | 77.4 ± 3.9 |

| 24 h | ||||||||

| saline | -5.46 ± 0.24 | 136.0 ± 32.4 | -6.79 ± 0.18 | 61.2 ± 4.7 | -7.64 ± 0.18 | 92.7 ± 2.7 | -7.03 ± 0.14 | 41.8 ± 4.8 |

| DEP | -5.46 ± 0.09 | 124.2 ± 11.4 | -6.86 ± 0.14 | 68.3 ± 6.3 | -7.81 ± 0.18 | 92.5 ± 2.2 | -7.07 ± 0.23 | 58.7 ± 6.5 |

| Mesenteric Artery | ||||||||

| 6 h | ||||||||

| saline | -6.02 ± 0.15 | 96.1 ± 3.6 | -7.29 ± 0.27 | 76.4 ± 7.8 | -7.82 ± 0.15 | 98.1 ± 2.2 | -8.19 ± 0.17 | 101.3 ± 0.7 |

| DEP | -5.76 ± 0.19 | 99.3 ± 3.9 | -7.51 ± 0.11 | 88.4 ± 3.6 | -8.36 ± 0.05** | 98.3 ± 1.4 | -8.80 ± 0.24 | 99.6 ± 1.2 |

| 24 h | ||||||||

| saline | -6.19 ± 0.11 | 103.6 ± 5.9 | -7.65 ± 0.23 | 82.0 ± 5.0 | -8.40 ± 0.15 | 99.1 ± 1.1 | -8.74 ± 0.16 | 102.4 ± 0.9 |

| DEP | -6.07 ± 0.11 | 132.9 ± 13.1 | -7.58 ± 0.17 | 80.6 ± 5.8 | -8.28 ± 0.19 | 99.3 ± 3.4 | -8.32 ± 0.21 | 102.5 ± 0.4 |

Results are mean ± SEM (n = 5-10), obtained by non-linear regression

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, control vs DEP, unpaired t-test.

EC50 - concentration producing 50% of maximum contraction

Emax - maximum contraction

IC50 - concentration producing 50% of maximum vasodilatation

Imax - maximum vasodilatation

To assess the possibility of the effects of DEP being apparent in blood vessels other than the thoracic aorta, vascular responses were also assessed in another conduit artery (femoral) and in a resistance artery (3rd order mesenteric). Responses to phenylephrine were similar in femoral and mesenteric arteries from DEP- and saline-treated animals (P > 0.05; Table 3). There were no differences in the responses to ACh between saline-instilled or DEP-instilled animals in either femoral (P > 0.36; Figure 4e) or mesenteric arteries (P > 0.08; Figure 4f) at either time point. Responses to other vasodilators were similar in these vessels from DEP and saline treated animals, with the exception that there was a significantly greater sensitivity to SNP in mesenteric arteries (P = 0.002; two-way ANOVA; IC50, P = 0.004) from DEP-treated rats (Table 3).

Discussion

Using a rat model, we have shown that acute pulmonary exposure to DEP induces both pulmonary and systemic inflammation, yet does not cause vascular endothelial dysfunction measured either in vivo or ex vivo.

In recent studies, we have shown both short- and long-term vascular and endothelial impairment in humans after exposure to diesel exhaust [8,9,11]. These effects appear to be mediated by the particulate components of the diesel exhaust [7,10]. To permit further investigation into the mechanism of DEP-induced vascular dysfunction, we exposed rats specifically to the particulate components of diesel exhaust via pulmonary instillation. Intratracheal instillation of particle suspensions has been shown to be a reliable way of producing excellent dispersion of particles throughout the lobes of rodent lungs and across the surface of the alveoli, leading to pulmonary effects that are directly comparable to that of inhalation studies [24-27]. Thus we used this method to test the hypothesis that DEP impairs endothelial function through the generation of pulmonary and systemic inflammation.

Inflammation has been implicated in many of the actions of DEP and other particles, including actions on the cardiovascular system [19]. It has been suggested that the pulmonary inflammation induced by particles leads to raised levels of inflammatory mediators within the circulation, that have detrimental actions on the vasculature. Pulmonary exposure to DEP produces a clear lung inflammation that peaks ~6-12 h after instillation and persists for over 24 h [18,20]. While the pulmonary actions of DEP are relatively consistent, measures of particle-induced systemic inflammatory response are notoriously variable [28-30]. In the present study we showed that DEP induced pulmonary inflammation 6 h after exposure. This was characterised by marked neutrophil infiltration, raised levels of the inflammatory mediator IL-6 and an increase in alveolar permeability, characterised by increased levels of protein in BALF. Pulmonary inflammation was largely resolved 24 h after exposure. While there was no indication of systemic inflammation at 6 h after DEP instillation, the levels of two inflammatory mediators, IL-6 and TNFα were increased in the plasma by 24 h after exposure. The time course of these responses could suggest that these factors originate from the prior inflammatory response in the lung. Previous studies in animals [31,32] and man [33,34] report raised levels of CRP in the blood following exposure to urban particulates or episodes of high air pollution, yet we did not find any changes in this mediator after DEP instillation. Differences in the type and composition of the particulate or co-pollutant may explain these discrepancies (see below). Regardless, these results highlight the need to measure multiple markers of inflammation to ensure that the systemic consequences of particle instillation are not overlooked.

In the present study we found that DEP instillation had no effect on endothelium-dependent vasodilatation, either in vivo or ex vivo. Previous studies have reported that DEP exposure by either inhalation or instillation is associated with endothelial dysfunction [35-37]. Similarly, exposure of rodents to urban PM has been reported to attenuate vascular function [38-41]. However, several studies have found that pulmonary exposure to DEP or urban PM, by both inhalation and instillation, had no effect on responses to vasodilators despite the high doses of particulate employed [42-44]. Similarly negative findings may be under-represented due to the tendency not to report negative data. The reason for these discrepancies is likely to be multifactorial, being influenced by dose and duration employed, type of particle, differences in animal species and blood vessel used as well as how the measurements are made.

The dose of particle used in the current study is high: approximately 30-fold higher than the comparable alveolar deposition from a 24 h inhalation of 100 μg/m3 in man (MPPD model, adjusted rat lung surface area) [45]. Thus, we do not believe that we have failed to observe an effect due to use of an inappropriately low dose. One of the notable differences between the present instillation study and real world exposures is that here we administer the particulate alone. Gases and semi-volatile compounds in whole diesel exhaust have the potential to produce vascular effects, although data from gaseous constituents alone is highly inconsistent and often only seen at high concentrations of these pollutants [44,46]. Furthermore, in our clinical exposures, the vascular action of diesel exhaust was abolished if particles were filtered from the emissions [7,10]. A second consideration is the composition of the particulate itself. The physiochemical properties of DEP vary markedly depending on the fuel used and the engine type and running conditions. In the present study we used widely available 'standard' DEP from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a frequently used source of DEP that acts as a benchmark for comparisons of the biological effects of DEP between studies. Interestingly isolated studies have shown that 'clean' carbon particles have the capacity to impair vascular function [47] or promote atherosclerosis [48]. Similarly, even nanoparticles believed to be inert (e.g. titanium dioxide nanoparticles) have occasional been reported to have vascular effects [41,49]. However, generally, the cardiovascular actions of these particles are small in comparison to that of urban PM or DEP [50,51], and are not evident in controlled exposures in humans [10]. Therefore, the quantities and properties of surface chemicals within DEP (e.g. organic constituents, transition metals) could account from a degree of variability between the vascular effects of different sources of DEP. Finally, species differences should also be considered, not just between human and rodent models, but also between different animal species, source of animals (e.g. inbred vs outbred animals) and the use of different animal models of disease.

Experiments in the present study were specifically designed to maximise the chances of detecting alterations in vascular function by making measurements in vivo where the neurohumoural systems are intact, as well as ex vivo both in conduit and resistance arteries. In the anaesthetised rat, both the endothelium-dependent vasodilator ACh and the endothelium-independent vasodilator SNP induced an increase in hind-limb blood flow. Both agents were delivered locally via the femoral artery to avoid reduction of systemic blood pressure and the associated reflex vasoconstriction [52], although there was a tendency for SNP to induce a small transient reduction in mean arterial blood pressure, suggesting a small degree of systemic activity. In animals that had received DEP 6 h prior to assessment of vascular function, responses to ACh in the hind-limb resistance bed were not different from those achieved in saline-instilled animals. This contrasts with our clinical studies in the forearm resistance bed, in which endothelium-dependent relaxation was impaired after diesel exhaust exposure [8,9,11]. The in vivo measurements were supported by a lack of effect of DEP on vascular function ex vivo. This lack of effect of DEP disproves our original hypothesis that pulmonary exposure to this particulate will impair vasodilator responses. However, the results do provide important insights into the mechanism of the cardiovascular effects of instilled DEP. Importantly, endothelial function was preserved at times when there was significant pulmonary (6 h) and systemic (24 h) inflammation, suggesting that inflammation alone is unlikely to account for the cardiovascular actions of inhaled particulates. Indeed, other studies have demonstrated endothelial dysfunction without inflammation [53,54], supporting the notion that the two phenomena are independent.

Endothelium-independent relaxation (SNP, isoprenaline) ex vivo was also unaffected by DEP instillation, suggesting that the ability of smooth muscle to relax is not impaired following exposure to DEP in vivo. However, in contrast, the increase in hind-limb blood flow induced by SNP in vivo was impaired both 6 and 24 h after administration of DEP. The change in blood flow in vivo depends on the balance between vasorelaxation and vasoconstriction after drug administration. The fact that the increase in hind-limb blood flow induced by SNP is reduced in animals that received DEP could, therefore, be the result of reduced vasorelaxation. A change in muscle sensitivity is unlikely as responses to ACh were not affected and we could not detect any change ex vivo, but we cannot rule out a change in bioactivity as a result of, say, increased oxidative stress [12,55] localised to the site of NO release from SNP. The reduced response to SNP could also be explained by increased vasoconstriction due to other counteracting constrictor influences such as endothelin or angiotensin II, or to increased sympathetic nerve activity. Alterations in these pathways could account for the raised blood pressure following PM exposure [56-58], as evidenced by the increased baseline systolic blood pressure in DEP-instilled rats in the current study. Additionally, the latter hypothesis is attractive given the evidence in the literature for increased autonomic activity and baroreceptor sensitivity in response to PM [17,59-62]. However, at present we can only speculate on the mechanism involved. Further experimentation is required to fully investigate the mechanisms involved.

Conclusions

Using a series of in vivo and ex vivo experiments we have shown that instillation of diesel exhaust particulate in rats causes both pulmonary and systemic inflammation, but this is not associated with impaired endothelial function. However, DEP administration produced specific impairments in the response to SNP in vivo that require further investigation.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult male Wistar rats (200-250 g; Charles River, Margate, UK; at least 4 animals per treatment group) were housed under controlled environmental conditions (21 ± 2°C; 12 h light/dark cycle) with access to tap water and standard laboratory rat chow ad-libitum. All rats were allowed to acclimatize to the environment for at least one week before experimental procedures were initiated. All experiments were performed according to the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (U.K. Home Office).

Pulmonary instillation of DEP

DEP (SRM-2975; National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, USA) was suspended in 0.9% sterile saline at a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL and sonicated for 5 min (70% power; 5 Hz) in an ice bath using a probe-type sonicator (US70; Philip Harris Scientific, Lichfield, U.K.) to minimise particulate aggregation.

DEP was administered by intra-tracheal instillation as previously described [59]. Briefly, rats were anesthetised, using 5% isoflurane inhalation (Meriol, Essex, UK), and positioned head-upwards on a board inclined at a 45° angle. The vocal chords were visualised by passing a pediatric laryngoscope with a plastic cannula into the trachea. Particles (0.5 mg/rat) or vehicle (saline) were then instilled as a 0.5 mL bolus. The dose used is comparable to previous studies [20,30,63,64] and preliminary experiments showed that this dose of DEP induces systemic effects without acute toxicity [59]. An additional group of non-instilled rats was used to confirm that saline instillation itself did not have significant pulmonary and systemic actions.

Collection and analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

Immediately after sacrifice BALF was collected for assessment of the inflammatory responses in the lungs of instilled animals, as described [59]. Briefly, the trachea was exposed and cannulated (0.3 mm O.D., stainless steel) allowing the lungs to be lavaged with 8 mL of sterile saline. The lungs were gently aspirated and the process repeated a further three times (24 ml total). BALF was centrifuged at 1800 g for 5 min. The supernatant from the first lavage was separated into 1 mL aliquots and stored at -80°C until required for biochemical determination. Total protein levels in BALF were determined using a standard bicinchoninic acid kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Northumberland, UK) to assess alveolo-capillary permeability as an indicator of lung inflammation. Additionally BALF was analysed for changes in the inflammatory mediators, C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; DuoSet kits, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The cell pellets from all lavages were resuspended in 1 mL of physiological saline and combined. Total cell number was measured using an automatic cell counter (Sartorius Steadman, Chemometec, Nuclecounter®, Gydevang, Denmark (941-0002)). For cell differentials, cytospin preparations were performed by centrifuging (300 rpm for 3 min; Shandon cytospin 3 centrifuge) 10,000 cells in 300 μL phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin onto Superfrost Plus glass slides (VWR International, Lutterworth, UK). Cytospins were air-dried, fixed with 100% methanol (1 min) and then stained using Diff-Quik™ (Raymond A. Lamb, London, UK). The differential cell count was performed from an average of 300 cells per slide using a hemocytometer (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) under 400 × magnification. BALF was collected following completion of the vascular measurements under anaesthesia (see below). Data obtained for all parameters were similar to those collected previously from animals that had not undergone this surgical intervention (data not shown).

Hematological assays

Blood was taken from the carotid artery immediately before sacrifice into ice-cooled tubes containing heparin (final concentration 100 U/mL). The mean values of different hematological parameters; white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets; were measured with the Coulter®Ac.T series analyzer (Coulter Corporation, Miami, USA). The remaining blood was centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min to isolate plasma, which was used for assessment of systemic inflammation by measuring CRP (DuoSet kit), TNFα (Quantikine kit) and IL-6 (Quantikine kit) by ELISA (R & D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Blood was collected following completion of the vascular measurements under anaesthesia (see below). Data obtained for all parameters were similar to those from animals that had not undergone this surgical intervention (data not shown).

In vivo vascular function in the hind-limb

Vascular function was studied 6 or 24 h after instillation to assess changes in vascular response over the course of the DEP-induced inflammatory response. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% for induction and 2-2.5% for maintenance) and body temperature was maintained at 37°C with a thermostatically-controlled under-blanket (Homeothermic Blanket Control Unit, Harvard Apparatus, UK). The right carotid artery was exposed by blunt dissection, cannulated with a heparinised saline-filled (final concentration 100 U/mL) polyethylene tube, and connected to a fluid filled pressure transducer (Powerlab/4SP, ADInstruments, UK) for continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure (systolic, diastolic and mean) and heart rate.

Vascular responses to drugs administrated intra-arterially were monitored in the left hind-limb based on the method of Jackson et al. (2010) [65]. For drug delivery the right femoral artery was exposed and a polyethylene cannula (0.61 mm o.d., 0.28 mm i.d., Portex, Jencons Scientific Ltd, Bedfordshire, UK) was inserted, gently advanced until its tip reached the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta and secured with silk ligatures at the point of insertion. For flow measurements, a midline incision was performed in the abdominal wall and the left iliac artery just distal to the aortic bifurcation was carefully isolated from surrounding tissue. A flow probe (type 0.7 V; Transonic Systems, Norfolk) was positioned around the artery and covered with surgical lubricating jelly (Fougera, Atlanta). Hind-limb blood flow (mm/min) was monitored continuously throughout the study via a Transonic TS420 flowmeter (Transonic Systems) connected to a MacLab/4e (AD instruments, AD Instruments, Sussex, UK) data acquisition system. Upon attaining a steady blood flow, boluses of the endothelium-dependent vasodilator ACh (0.07 and 0.7 μg) were delivered in a volume of 10 μL via a microsyringe (25 μL, Hamilton Bonaduz AG, Bonaduz, Switzerland) attached to the cannula leading to the abdominal aorta. Injection of 10 μL saline itself had no effect on hind-limb blood flow. ACh and saline were given in a randomised order, followed by increasing doses of the endothelium-independent, nitric oxide donor SNP (0.09 and 0.9 μg). Preliminary studies in our laboratory suggested that these doses of ACh and SNP are sufficient to increase blood flow in the hind-limb while avoiding spill-over into the systemic circulation and influencing mean blood pressure, as compared with identical doses of acetylcholine and SNP given intravenously (data not shown). Blood flow was allowed to return to baseline before administering the next drug. Femoral vascular conductance (FVC) was calculated as femoral blood flow/mean arterial pressure.

Ex vivo vascular function using myography

The thoracic aorta, a region of uninjured femoral artery and 3rd order mesenteric resistance arteries were isolated from animals 6 or 24 h after instillation, and cleaned of connective tissue. Segments of aorta (~5 mm length), femoral and mesenteric arteries (both 1-2 mm length) were mounted in a multi-myograph system (610 M; Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) [12], using 40 μm diameter wire for smaller vessels. Vessels were submerged in Krebs buffer (composition in mM: 118.4 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 0.027 ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2.5 CaCl2) bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2 at 37°C before a baseline tension of 14.7 mN (aorta), 8 mN (femoral) or 4 mN (mesenteric) was gradually applied over 10 min and vessels were allowed to equilibrate for a further 30 min. Preliminary experiments showed that these pretension levels produced optimal contraction and dilatation responses. Data from force transducers were processed by a MacLab/4e analogue-digital converter displayed through Chart™ software (AD Instruments, Sussex, UK).

Vessel viability was confirmed by a contractile response on addition of 80 mM KCl, repeated 3 times (aorta) or serial addition of high K+Krebs (Krebs with substitution of 4.7 mM NaCl and 118.4 mM KCl) together with 10 μM noradrenaline (femoral and mesenteric arteries). Concentration-response curves to phenylephrine (PE; 1 nM - 10 μM) were obtained and a concentration that produced 80% maximum contraction (EC80; 0.1-1 μM) was chosen for each individual arterial segment. Following sub-maximal contraction with the appropriate concentration of PE, cumulative concentration-response curves were obtained for acetylcholine (1 nM - 10 μM), SNP (0.1 nM - 3 μM) and a nitric oxide-independent vasodilator (isoprenaline; 0.1 nM - 10 μM). At least 30 min washout was allowed before application of subsequent drugs.

Blood vessels were isolated from taken from regions undamaged by the surgical procedure, from animals that had undergone vascular measurements in vivo. To obtain sufficient n-numbers for all vessel types, blood vessels were also obtained from additional animals that had not undergone the surgical procedure. Responses were identical in both groups of animals, therefore, the data-sets were combined.

Drugs and reagents

Krebs salts were obtained from VWR International (Lutterworth, UK). All other drugs were obtained from Sigma Ltd. (Poole, UK). All drugs were dissolved and diluted in saline or Krebs buffer. Preliminary experiments confirmed that, in all cases, addition of vehicle alone had no effect on any of the parameters measured.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences in FVC response were expressed as a change from baseline. Myography responses are expressed as percentage of the pre-contraction to EC80 PE, where positive values represent vasodilatation and 100% vasodilatation represents a complete abolition of PE-induced tone. Statistical comparisons were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post-hoc tests (pulmonary and systemic inflammation), two-way ANOVA using the Bonferroni post-hoc test (blood flow and blood pressure, ex vivo concentration response curves) or unpaired Student's t-test (ex vivo EC50 and Emax values), unless otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (V5.0; GraphPad Software Inc, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Abbreviations

ACh: acetylcholine; ANOVA: analysis of variance; BALF: bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; CRP: C-reactive protein; DEP: diesel exhaust particulate; FVC: femoral vascular conductance; HBF: hind-limb blood flow; IL-6: Interleukin 6; NIST: National Institute of Standards and Technology; PE: phenylephrine; PM: particulate matter; SEM: standard error of the mean; SNP: sodium nitroprusside; TNFα: tumour necrosis factor alpha.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SR carried out the in vivo vascular studies and measures of inflammation, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. GAG conceived the in vivo study, participated in its design and coordination, helped to draft the manuscript. RD assisted with the particle instillations and design of the pulmonary assays. SGM carried out the aortic ex vivo vascular studies. PWFH participated in the design of the study, the surgical procedures and helped to draft the manuscript. CAS and DEN helped to draft the manuscript. MRM carried out the femoral and mesenteric ex vivo vascular studies and statistical analysis, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sarah Robertson, Email: srobertson@salud.unm.edu.

Gillian A Gray, Email: gillian.gray@ed.ac.uk.

Rodger Duffin, Email: Rodger.Duffin@ed.ac.uk.

Steven G McLean, Email: smclean1@staffmail.ed.ac.uk.

Catherine A Shaw, Email: catherine.shaw@ed.ac.uk.

Patrick WF Hadoke, Email: phadoke@staffmail.ed.ac.uk.

David E Newby, Email: D.E.Newby@ed.ac.uk.

Mark R Miller, Email: Mark.Miller@ed.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a British Heart Foundation Programme Grant (RG/05/003) and a 4-year British heart Foundation PhD Studentship (FS/07/063) with additional financial support for equipment from a University of Edinburgh Development Trust Small Project Grant. We also acknowledge the support of the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence (CoRE) award.

Funding

British Heart Foundation Programme Grant (RG/05/003), 4-year British Heart Foundation PhD Studentship (FS/07/063) and a University of Edinburgh Development Trust Small Project Grant. The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Bhatnagar A. Environmental cardiology: studying mechanistic links between pollution and heart disease. Circ Res. 2006;99:692–705. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243586.99701.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Brook JR, Rajagopalan S. Air pollution: the "Heart" of the problem. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:32–39. doi: 10.1007/s11906-003-0008-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, Ferris BG Jr, Speizer FE. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Report 2002. [accessed 2007]

- Oberdorster G. Pulmonary effects of inhaled ultrafine particles. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001;74:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s004200000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulig A, Sourdeval M, Meyer M, Marano F, Baeza-Squiban A. Biological effects of atmospheric particles on human bronchial epithelial cells. Comparison with diesel exhaust particles. Toxicol In Vitro. 2003;17:567–573. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(03)00115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucking AJ, Lundback M, Barath SL, Mills NL, Sidhu MK, Langrish JP, Boon NA, Pourazar J, Badimon JJ, Gerlofs-Nijland ME, Cassee FR, Boman C, Donaldson K, Sandstrom T, Newby DE, Blomberg A. Particle traps prevent adverse vascular and prothrombotic effects of diesel engine exhaust inhalation in men. Circulation. 2011;123:1721–1728. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.987263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Robinson SD, Gonzalez M, Darnley K, MacNee W, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, Newby DE. Diesel exhaust inhalation causes vascular dysfunction and impaired endogenous fibrinolysis. Circulation. 2005;112:3930–3936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornqvist H, Mills NL, Gonzalez M, Miller MR, Robinson SD, Megson IL, Macnee W, Donaldson K, Soderberg S, Newby DE, Sandstrom T, Blomberg A. Persistent endothelial dysfunction in humans after diesel exhaust inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:395–400. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-872OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills NL, Miller MR, Lucking AJ, Beveridge J, Flint L, Boere AJ, Fokkens PH, Boon NA, Sandstrom T, Blomberg A, Duffin R, Donaldson K, Hadoke PW, Cassee FR, Newby DE. Combustion-derived nanoparticulate induces the adverse vascular effects of diesel exhaust inhalation. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(21):2660–71. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Gonzalez MC, Vink E, Robinson SD, Soderberg S, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Sandstrom T, Blomberg A, Newby DE. Ischemic and thrombotic effects of dilute diesel-exhaust inhalation in men with coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1075–1082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MR, Borthwick SJ, Shaw CA, McLean SG, McClure D, Mills NL, Duffin R, Donaldson K, Megson IL, Hadoke PW, Newby DE. Direct impairment of vascular function by diesel exhaust particulate through reduced bioavailability of endothelium-derived nitric oxide induced by superoxide free radicals. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:611–616. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JS, Zeman KL, Bennett WD. Ultrafine particle deposition and clearance in the healthy and obstructed lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1240–1247. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-399OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyling WG, Semmler M, Erbe F, Mayer P, Takenaka S, Schulz H, Oberdorster G, Ziesenis A. Translocation of ultrafine insoluble iridium particles from lung epithelium to extrapulmonary organs is size dependent but very low. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:1513–1530. doi: 10.1080/00984100290071649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorster G, Sharp Z, Atudorei V, Elder A, Gelein R, Kreyling W, Cox C. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine particles to the brain. Inhal Toxicol. 2004;16:437–445. doi: 10.1080/08958370490439597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills NL, Amin N, Robinson SD, Anand A, Davies J, Patel D, de la Fuente JM, Cassee FR, Boon NA, Macnee W, Millar AM, Donaldson K, Newby DE. Do inhaled carbon nanoparticles translocate directly into the circulation in humans? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:426–431. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-865OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoden CR, Wellenius GA, Ghelfi E, Lawrence J, Gonzalez-Flecha B. PM-induced cardiac oxidative stress and dysfunction are mediated by autonomic stimulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1725:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmar A, Nemery B, Hoet PH, Vermylen J, Hoylaerts MF. Pulmonary inflammation and thrombogenicity caused by diesel particles in hamsters: role of histamine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1366–1372. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-801OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton A, MacNee W, Donaldson K, Godden D. Particulate air pollution and acute health effects. Lancet. 1995;345:176–178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden MC, Richards JH, Dailey LA, Hatch GE, Ghio AJ. Effect of ozone on diesel exhaust particle toxicity in rat lung. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;168:140–148. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills NL, Robinson SD, Fokkens PHB, Leseman DLAC, Miller MR, Anderson D, Freney EJ, Heal MR, Donovan RJ, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, MacNee W, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Newby DE, Cassee FR. Exposure to concentrated ambient particles does not affect vascular function in patients with coronary heart disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:709–715. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiston JR, Davidson W, Attridge S, Li GT, Brauer M, van Eeden SF. Wood smoke exposure induces a pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response in firefighters. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:129–138. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00097707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson RF. Use of bronchoalveolar lavage to detect respiratory tract toxicity of inhaled material. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2005;57(Suppl 1):155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson RF, Driscoll KE, Harkema JR, Lindenschmidt RC, Chang IY, Maples KR, Barr EB. A comparison of the inflammatory response of the lung to inhaled versus instilled particles in F344 rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1995;24:183–197. doi: 10.1006/faat.1995.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyabara Y, Ichinose T, Takano H, Sagai M. Diesel exhaust inhalation enhances airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;116:124–131. doi: 10.1159/000023935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyabara Y, Takano H, Ichinose T, Lim HB, Sagai M. Diesel exhaust enhances allergic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1138–1144. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9708066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KE, Costa DL, Hatch G, Henderson R, Oberdorster G, Salem H, Schlesinger RB. Intratracheal instillation as an exposure technique for the evaluation of respiratory tract toxicity: uses and limitations. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2000;55:24–35. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/55.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmar A, Zia S, Subramaniyan D, Fahim MA, Ali BH. Exacerbation of thrombotic events by diesel exhaust particle in mouse model of hypertension. Toxicology. 2011;285:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottipolu RR, Wallenborn JG, Karoly ED, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Krantz T, Linak WP, Nyska A, Johnson JA, Thomas R, Richards JE, Jaskot RH, Kodavanti UP. One-month diesel exhaust inhalation produces hypertensive gene expression pattern in healthy rats. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:38–46. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota S, Seki T, Naito Y, Tachibana S, Hirabayashi N, Nakasaka T, Ohara N, Kobayashi H. Tracheal instillation of diesel exhaust particles component causes blood and pulmonary neutrophilia and enhances myocardial oxidative stress in mice. J Toxicol Sci. 2008;33:609–620. doi: 10.2131/jts.33.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay S, Ganguly K, Stoeger T, Semmler-Bhenke M, Takenaka S, Kreyling WG, Pitz M, Reitmeir P, Peters A, Eickelberg O, Wichmann HE, Schulz H. Cardiovascular and inflammatory effects of intratracheally instilled ambient dust from Augsburg, Germany, in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Xie Y, Qian X, Jiang R, Song W. Acute effects of fine particles on cardiovascular system: differences between the spontaneously hypertensive rats and wistar kyoto rats. Toxicol Lett. 2010;193:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Frohlich M, Doring A, Immervoll T, Wichmann HE, Hutchinson WL, Pepys MB, Koenig W. Particulate air pollution is associated with an acute phase response in men; results from the MONICA-Augsburg Study. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1198–1204. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu RS, Petroni DH, George WJ. Ambient particulate matter, C-reactive protein, and coronary artery disease. Inhal Toxicol. 2005;17:409–413. doi: 10.1080/08958370590929538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherng TW, Campen MJ, Knuckles TL, Gonzalez Bosc LV, Kanagy NL. Impairment of coronary endothelial cell ETB receptor function following short-term inhalation exposure to whole diesel emissions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297(3):R640–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90899.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuckles TL, Lund AK, Lucas SN, Campen MJ. Diesel exhaust exposure enhances venoconstriction via uncoupling of eNOS. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodavanti UP, Thomas R, Ledbetter AD, Schladweiler MC, Shannahan JH, Wallenborn JG, Lund AK, Campen MJ, Butler EO, Gottipolu RR, Nyska A, Richards JE, Andrews D, Jaskot RH, McKee J, Kotha SR, Patel RB, Parinandi NL. Vascular and cardiac impairments in rats inhaling ozone and diesel exhaust particles. Environ Heal Perspect. 2011;119:312–318. doi: 10.1289/ehp.119-a312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi E, Hazarika S, Stallings HW, Cascio WE, Devlin RB, Lust RM, Wingard CJ, Van Scott MR. Ultrafine particulate matter exposure augments ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H894–903. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01362.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido T, Tamagawa E, Bai N, Suda K, Yang HH, Li Y, Chiang G, Yatera K, Mukae H, Sin DD, Van Eeden SF. Particulate matter induces translocation of IL-6 from the lung to the systemic circulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:197–204. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0427OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagawa E, Bai N, Morimoto K, Gray C, Mui T, Yatera K, Zhang X, Xing L, Li Y, Laher I, Sin DD, Man SF, van Eeden SF. Particulate matter exposure induces persistent lung inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L79–L85. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00048.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc AJ, Cumpston JL, Chen BT, Frazer D, Castranova V, Nurkiewicz TR. Nanoparticle inhalation impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation in subepicardial arterioles. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:1576–1584. doi: 10.1080/15287390903232467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagate K, Meiring JJ, Gerlofs-Nijland ME, Vincent R, Cassee FR, Borm PJ. Vascular effects of ambient particulate matter instillation in spontaneous hypertensive rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;197:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlofs-Nijland ME, Totlandsdal AI, Kilinc E, Boere AJ, Fokkens PH, Leseman DL, Sioutas C, Schwarze PE, Spronk HM, Hadoke PW, Miller MR, Cassee FR. Pulmonary and cardiovascular effects of traffic-related particulate matter: 4-week exposure of rats to roadside and diesel engine exhaust particles. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:1162–1173. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.531062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan C, Sun Q, Lippmann M, Chen LC. Comparative effects of inhaled diesel exhaust and ambient fine particles on inflammation, atherosclerosis, and vascular dysfunction. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:738–753. doi: 10.3109/08958371003728057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassee FR, Muijser H, Duistermaat E, Freijer JJ, Geerse KB, Marijnissen JC, Arts JH. Particle size-dependent total mass deposition in lungs determines inhalation toxicity of cadmium chloride aerosols in rats. Application of a multiple path dosimetry model. Arch Toxicol. 2002;76:277–286. doi: 10.1007/s00204-002-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campen MJ, Lund AK, Knuckles TL, Conklin DJ, Bishop B, Young D, Seilkop S, Seagrave J, Reed MD, McDonald JD. Inhaled diesel emissions alter atherosclerotic plaque composition in ApoE(-/-) mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;242:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesterdal LK, Folkmann JK, Jacobsen NR, Sheykhzade M, Wallin H, Loft S, Moller P. Pulmonary exposure to carbon black nanoparticles and vascular effects. Particle and Fibre Toxicology. 2010;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y, Hiura Y, Murayama T, Yokode M, Iwai N. Nano-sized carbon black exposure exacerbates atherosclerosis in LDL-receptor knockout mice. Circulation journal: official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2007;71:1157–1161. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Hubbs AF, Cumpston JL, Chen BT, Frazer DG, Castranova V. Nanoparticle inhalation augments particle-dependent systemic microvascular dysfunction. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2008;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois A, Andujar P, Ladeiro Y, Baudrimont I, Delannoy E, Leblais V, Begueret H, Galland MA, Brochard P, Marano F, Marthan R, Muller B. Impairment of NO-dependent relaxation in intralobar pulmonary arteries: comparison of urban particulate matter and manufactured nanoparticles. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1294–1299. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurgueira SA, Lawrence J, Coull B, Murthy GG, Gonzalez-Flecha B. Rapid increases in the steady-state concentration of reactive oxygen species in the lungs and heart after particulate air pollution inhalation. Environ Heal Perspect. 2002;110:749–755. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabisch PA, Liles JT, Baber SR, Golwala NH, Murthy SN, Kadowitz PJ. Analysis of L-NAME-dependent and -resistant responses to acetylcholine in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H688–H698. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00394.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Barger M, Castranova V, Boegehold MA. Particulate matter exposure impairs systemic microvascular endothelium-dependent dilation. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1299–1306. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Barger M, Millecchia L, Rao KM, Marvar PJ, Hubbs AF, Castranova V, Boegehold MA. Systemic microvascular dysfunction and inflammation after pulmonary particulate matter exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:412–419. doi: 10.1289/ehp.114-a412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Yue P, Ying Z, Cardounel AJ, Brook RD, Devlin R, Hwang JS, Zweier JL, Chen LC, Rajagopalan S. Air pollution exposure potentiates hypertension through reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of Rho/ROCK. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1760–1766. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmar A, Dhanasekaran S, Yasin J, Ba-Omar H, Fahim MA, Kazzam EE, Ali BH. Evaluation of the direct systemic and cardiopulmonary effects of diesel particles in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Toxicology. 2009;262:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CC, Hwang JS, Chan CC, Cheng TJ. Interaction effects of ultrafine carbon black with iron and nickel on heart rate variability in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1012–1017. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Cao Q, Qian X, Xie Y. et al. Acute effects of fine particle on cardiovascular system of rats. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2007;36:417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen DS, Donaldson K, Bond SM, McNeilly JD, Newman S, Barton NJ, Duffin R. Bilateral vagotomy or atropine pre-treatment reduces experimental diesel-soot induced lung inflammation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;219:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold DR, Damokosh AI, Pope CA. Dockery DW, McDonnell WF, Serrano P, Retama A, Castillejos M: Particulate and ozone pollutant effects on the respiratory function of children in southwest Mexico City. Epidemiology. 1999;10:8–16. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, Lovett EG, Larson AC, Raizenne ME, Kanner RE, Schwartz J, Villegas GM, Gold DR, Dockery DW. Heart rate variability associated with particulate air pollution. Am Heart J. 1999;138:890–899. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(99)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellenius GA, Saldiva PH, Batalha JR, Krishna Murthy GG, Coull BA, Verrier RL, Godleski JJ. Electrocardiographic changes during exposure to residual oil fly ash (ROFA) particles in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Toxicol Sci. 2002;66:327–335. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/66.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, BeruBe KA, Pooley FD, Richards RJ. The response of lung epithelium to well characterised fine particles. Life Sci. 1998;62:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YH, Huang CH, Chen WJ, Wu MF, Cheng TJ. Effects of diesel exhaust particles on left ventricular function in isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury and healthy rats. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:199–203. doi: 10.1080/08958370701861082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN, Ellis CG, Shoemaker JK. Estrogen modulates the contribution of neuropeptide Y to baseline hindlimb blood flow control in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1351–R1357. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00420.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]