Abstract

The development of separation response behaviors in infant rhesus macaques across the first 6 months of life was assessed. Seventeen infants underwent a neonatal assessment at 7, 14, 21, and 30 days of age which included a brief period of social isolation. At 3 and 6 months of age these same monkeys and four additional subjects were again subjected to a period of brief social isolation and also exposed to a novel environment with their sedated mother. Results indicate a developmental increase followed by a steady decline in the frequency of separation vocalizations. A modest relationship between early-infancy locomotor profiles and separation responses was also observed at several time points suggesting a possible relationship between these measures. However, stable inter-individual measures of separation distress did not emerge until late in the infantile period. This could suggest that high levels of maternal contact-seeking behavior early in infancy are context specific and not a reliable index of enduring temperament.

Keywords: INFANT, SEPARATION, ANXIETY, ATTACHMENT

In many mammals the mother is the sole provider of nourishment, hydration, warmth and protection for the infant and maintaining close physical proximity with the mother is essential for the infants’ survival. Because of this, emotional systems and behavioral signals have evolved in both mothers and infants which encourage physical proximity throughout the infantile period (Bowlby, 1952; Harlow, Dodsworth, & Harlow, 1965; Hofer & Sullivan, 2001; Panksepp, Nelson, & Bekkedal, 1997).

Under natural conditions proximity maintenance is a dynamic process mediated by interaction between infant and mother. The mother’s role is initially an active one: she carries, retrieves, and restrains the infants. Infants on the other hand have both an active approach response which includes orienting, following and clinging to the mother and a more passive separation signaling response that is triggered by maternal absence (Hofer & Sullivan, 2001; Panksepp et al., 1997). Both the active and passive behaviors of infants have been studied extensively in animal and human studies to inform theories of attachment, social neurobiology, and temperament (Ainsworth, 1985; Finkel & Matheny, 2000; Gunnar, Larson, Hertsgaard, Harris, & Brodersen, 1992; Hofer & Sullivan, 2001; Kalin, Shelton, & Lynn, 1995; Levine, Franklin, & Gonzalez, 1984; Nelson & Panksepp, 1998; Rilling, Winslow, O’Brien, Gutman, Hoffman, & Kilts, 2001; Zeifman, 2001). The most prominent component of the separation response is a separation vocalization which gains attention of the mother and may indicate its location. In rhesus monkeys the “coo” call is the primary distress vocalization emitted by infants when separated from their mother (Kalin & Shelton, 1989; Levine et al., 1984; Levine, Wiener, Coe, Bayart, & Hayashi, 1987; Mitchell, 1968; Singh, 1975).

One feature of the infants’ separation response which has received relatively less attention is the normative change that takes place across early development. As the infant gradually gains independence, the need for the mother declines which should also be reflected in a reduction in motivation to keep the mother close. A number of observational studies under both naturalistic and semi-naturalistic conditions has demonstrated a dramatic reduction in infant-mother interactions in rhesus monkeys across the first 6 months of life (Berman, 1980; Hinde & Spencer-Booth, 1967; Suomi, 2005). For example for the first several weeks after birth, infants spend greater than 80% of their time in ventral contact with their mother but this declines to 40% by twelve weeks of age and 20% by 24 weeks (Berman, 1980). This change in behavior is a function of alterations in both infant solicitations for maternal contact and in mothers allowing infants to have access to them (Hinde & White, 1974). Indeed in rhesus monkeys, it appears that the mother’s behavior may play a greater role in infant transitions away from her than the infants’ solicitations of maternal contact (Hinde & McGinnis, 1977; Hinde & White, 1974).

However, infants also participate in this process of independence and this is reflected in motivational shifts across development. Previous studies have noted a marked reduction in the frequency of coo calls that occur as a consequence of separation between 4 and 8 months of age in rhesus monkeys (Kalin & Shelton, 1998). More systematic studies of development in rodents have found an inverted u-shaped curve in separation calls across development. In rat pups, the frequency of separation induced ultrasonic vocalizations increases over the first days of life which likely reflects motoric development, and then gradually declines as the infant approaches weaning age (Brunelli & Hofer, 1996; Hofer, Shair, Masmela, & Brunelli, 2001; Noirot, 1968). Observational studies across a wide range of cultures have found a very similar developmental pattern of crying in human infants which increases through 6-8 weeks of life and then gradually declines over the ensuing months (Barr, 1990; Konner, 2010; St James-Roberts, Conroy, & Wilsher, 1998).

Although the separation response has adaptive features, it can also have adverse consequences. For instance, rearing in an environment with either prolonged or repeated maternal separations is associated with lifelong dysregulation of physiological systems and an increased risk of pathological emotional development (Coplan, Smith, Altemus, Scharf, Owens, Nemeroff, Gorman, & Rosenblum, 2001; Levine, 2005; Meaney, 2001; Rutter, Kreppner, & Sonuga-Barke, 2009). Furthermore, acute separations are associated with bouts of intense anxiety. Indeed, the anxiolytic capacity of pharmacological agents across a variety of contexts is often tightly associated with their ability to attenuate the separation response (Iijima & Chaki, 2005; Miczek, Tornatsky, & Vivian, 1991; Winslow & Insel, 1991) suggesting that maternal separation is associated with strong negative affect. Finally, marked individual variability in separation responses exist in many mammalian species. In humans, when these responses appear particularly marked, or are particularly disruptive they are considered to be symptoms of separation anxiety disorder (SA), an early form of psychopathology that predicts risk for later emotional problems over decades (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009). Uncovering the normative developmental trajectory of proximity maintenance behaviors may be particularly important for understanding pathological emotional responses such as occur in SA in humans. Deviations from normative developmental curves may shed light on personality or temperamental response patterns and on psychopathologic responses such as SA in humans.

Another important aspect of separation and proximity seeking responses for understanding individual response patterns is the degree of stability of responding within individuals across time and across contexts. While some have argued that the separation response may be a good marker of anxious temperament others have suggested that the separation response does not have good stability either across time or context (Barr, 1990). Recent studies in human adults have found that differences in the response to separation may be partially under under genetic control (Way, Taylor, & Eisenberger, 2009). This finding suggests that stable individual differences should emerge at some point. Therefore the developmental trajectory of the proximity seeking response may be an important aspect of the temperamental component as it raises the question of not only whether stability is achieved but also when it is achieved. If stable inter-individual patterns are transient then they may be less meaningful as a predictor of anxiety, but if they coalesce at a particular point in development then that provides guidelines for when assessments of extreme separation responses should be performed.

Although normative patterns of separation distress and proximity seeking have been characterized in rodent models (Hofer et al., 2001; Noirot, 1968; Thiels, Alberts, & Cramer, 1990), clear models of this developmental process are lacking in nonhuman primates. Although there is a literature of developmental change in infant-mother interaction in both human and nonhuman primates (Ainsworth, 1985; Barr, 1990; Berman, 1980; Hinde & Spencer-Booth, 1967; Suomi, 2005) these are largely based on observational studies and the specific contributions of infants to this change is often difficult to infer (Hinde & McGinnis, 1977). Furthermore, with the growing interest in the relationship between temperament and psychopathology particularly in relation to continuity and discontinuity across development (Degnan & Fox, 2007; Degnan, Henderson, Fox, & Rubin, 2008; Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005), we sought to understand when meaningful individual differences in variability in temperament and psychopathology emerge and to what extent this is mediated by development. Because of the similarity in neurobiology, development, and social patterns between rhesus monkeys and humans we sought to characterize the normative pattern of maternal proximity maintenance behaviors in a group of captive rhesus monkeys across the first 6 months of life. This study is focused on the separation response and separation induced vocalizations when the infant is removed from the mother and other conspecifics, but not on normal proximity maintenance behavior in the home group. We made two primary predictions: first separation induced vocalizations would change across development declining to the lowest levels at the time of weaning; and second stable inter-individual differences in these behaviors would emerge late in the infantile period. Additionally as some previous studies in humans have observed a relationship between developmental patterns of motor systems and development of emotional temperament (DiPietro, Bornstein, Costigan, Pressman, Hahn, Painter, Smith, & Yi, 2002), we also performed exploratory analyses on this relationship. To the extent that maintaining proximity with the mother co-develops with other behaviors, either because of some generalized rate of development or because they are interdependent we expected correlations with other indices of development to emerge based on prior findings.

Methods

Subjects

This study is part of an ongoing longitudinal analysis of temperament and development in rhesus monkeys at the NIH animal facility in Poolesville, Maryland. Our protocol involves screening infants with the modified Brazelton infant assessment battery across the first month of life (Schneider, Moore, Suomi, & Champoux, 1991), and then assessing again at 3 and 6 months of age with a modified version of a more age appropriate temperament battery (Bethea, Streicher, Coleman, Pau, Moessner, & Cameron, 2004). In the present study twenty-one infants (12 males, 9 females) were assessed at 3 and 6 months of age, but four of these infants were not available for testing during infancy, so only 17 (9 males and 8 females) were assessed at all time points. Longitudinal analyses that included all time points therefore only included 17 subjects, but analyses that were restricted to the older age groups included all 21 subjects. All subjects were rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) from a single birth-year cohort. Subjects were bred and subsequently housed in an indoor-outdoor “run” at the NIH animal facility, Poolesville, MD. Each run contained one adult male and eight to ten females and their offspring. Animals were fed daily and had ad-libitum access to water. Runs were checked daily for birth and overall health status of monkeys by an animal caretaker. All procedures were approved by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Animal Care and Use Committee.

Procedures

Assessment during first month

At postnatal days 7, 14, 21 and 30 infants were removed from the mother and an adaptation of the Brazelton Neonatal Assessment was performed by a trained observer. The details of this procedure have been described previously (Schneider et al., 1991; Schneider & Suomi, 1992). Briefly, the infant was removed from the mother and over the course of approximately 15 minutes, a series of brief probes of motor, emotional and perceptual development were performed on the infant by a human experimenter. For example the fine motor skills, visual orienting, and startle response to a loud nose were all rated on a 5 point scale. At the end of the active assessment battery, the infant was then placed alone and undisturbed in an incubator cage with a toy and blanket for an additional 5 min. The infant was then returned to its home cage where it remained undisturbed (aside from routine animal care procedures) until the next test session. The number of vocalizations during the separation period was tabulated by a human observer. Vocalization was defined as any vocal sound emitted by the subject. Although rhesus monkeys do have a repertoire of different vocalizations (eg. coo, bark, screech, squeal), in infancy vocalization types are usually indistinguishable, and so during the infantile period we simply tabulated vocalization frequency without denoting vocalization type. Locomotion was defined as any self induced change in location that is not part of a stereotypy, including walking, patrolling, running, dropping from ceiling to floor, rolling, hopping on all fours and bouncing around the cage, and was scored on a 3 point scale

Assessments at 3 and 6 months of age

The 3 and 6 month assessments were each conducted over three sequential daily test sessions. On days 1 and 3 infants were removed from their mother and placed alone in a single cage in an unfamiliar testing room for 10 minutes where behavior was videotaped. On day 2 infants were removed from their home cage and placed in a novel environment and a modified version of the free play test was performed (Bethea et al., 2004; Cameron, Bacanu, Coleman, Dahl, Devlin, Rogers, Ryan, & Williamson, 2003; Williamson, Coleman, Bacanu, Devlin, Rogers, Ryan, & Cameron, 2003). Briefly this task consists of placing subjects in a novel test cage (91 × 260 × 183 cm) along with their mother and a variety of colorful toys (balls, rubber dog chews, small climbing apparatus). The mother was immobilized by administration of a Ketamine/Xylazine mix (7:3, 0.1mL/kg) and strapped to a human infant car seat on her back with ventrum exposed. Anesthetizing the mother enabled us to include the mother in the room as a salient stimulus for the infant while at the same time focus on behavior that was completely initiated by the infant without maternal interference. In order to prevent infants from obtaining milk (and anesthetic), the nipples were covered with an adhesive bandage. The infant was not restrained and therefore free to move about the room and explore novel objects inside the cage. The session lasted 40 minutes and was videotaped for subsequent analysis. The videos acquired during the 3 and 6 month assessment were subsequently scored using Observer 7.0 (Noldus, The Netherlands). The separation and free play videos were scored for frequency of “coo” vocalizations and the frequency and duration of bouts of locomotor activity. Coo, a tone of medium pitch and intensity formed with circular mouth and tensed lips, was the predominant vocalization type emitted during this test. Locomotion was defined as any self induced change in location which was not part of a stereotypic repeated movement. Locomotor behavior therefore included changes in walking, patrolling, running, jumping and climbing. The frequency and duration of time on mother was also tabulated from the free play video. This was defined as any physical contact between infant and mother. All behaviors were coded by trained observers with intra-rater reliability above .85 for all measures.

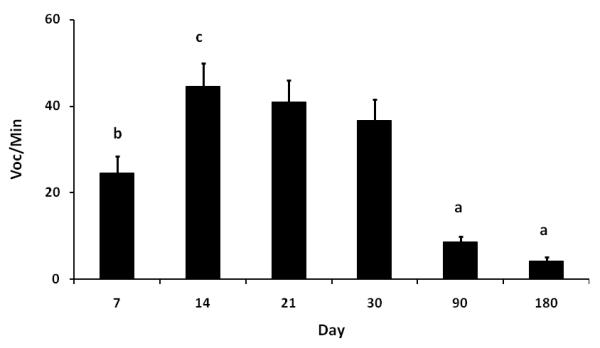

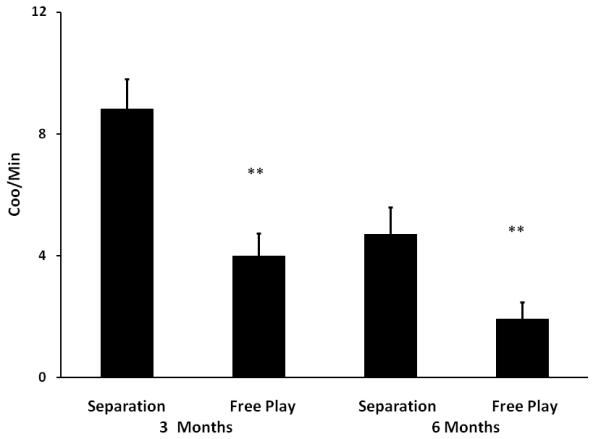

Data processing and Statistical Analysis

In order to facilitate developmental comparisons we first generated a mean vocalization of the two separation sessions at 3 and 6 months of age. Second to facilitate comparisons across the different testing conditions we converted all vocalization responses to a rate of vocalizations/minute. This resulted in a standard vocalization response at 6 postnatal time points: 7, 14, 21, 30, 60 and 180 days (see Fig 1) To ensure that any differences we attributed to development were not just a product of different rates of vocalization across the tests which were of different durations (i.e. 5 minutes of separation during the neonatal assessment, as opposed to 10 minutes of separation during the isolation condition, and 40 minutes during free-play). We only used the first 5 min of data from the 3 and 6 month separation to compare with the 5 min neonatal isolation response (Fig 1). We only used the first 10 min of the free-play test in direct comparisons with the 10-min isolation response and the sample size here is all 21 subjects (Fig 2). During the free play test, we compare the time infants spent on mother and off mother during the whole 40 minutes and the sample size here is all 21 subjects (Fig 3). Correlation of vocalization of infants during separation test and free play test was performed and the sample size here is all 21 subjects (Fig 4). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0). The primary analytic approaches used were analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures Pearson correlations, and the non parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. Deviations from normality were determined when the ratio of skewness to standard error of skewness exceded 2. Statistical threshold was set to p < 0.05

Fig 1.

Depicts the mean (+SEM) frequency of vocalizations per minute during separation sessions across the first 6 months of life.

Fig 2.

Mean (+SEM) frequency of coo vocalizations at 3 and 6 months of age during the separation condition and free play test in which the infant was placed in a room with their sedated mother. ** indicates p < 0.01

Fig 3.

Mean (+SEM) frequency of coo vocalizations during the separation and free play tests for groups high and low in physical contact with the mother at 3 and 6 months of age. High and low contact was determined by median split of contact time at each time point. * indicates p<.05.

Fig. 4.

Scatterplot of correlations between separation and free play vocalization frequency at 3 months (top panel) and 6 months of age (bottom panel).

Results

The Rate of Isolation Vocalization Changes Across Development

The number of coos/min at each test day was analyzed with a repeated measures ANOVA and a highly significant effect of test day was found (F(5,80) = 23.524, p < 0.001). Post-hoc comparison showed significant difference between day 90 and the rest of the days (all p < 0.001), day 180 and the rest of the days (all p < 0.001), day 7 and the rest of the days (all p < 0.05) except for day 30, day 14 and day 30 (p < 0.05). No significant difference was found between day 14 and day 21 or day 21 and day 30 indicating a plateau of response at this period of development. Results indicate an increasing tendency of isolation vocalization from day 7, reaching a plateau during day 14 and then a decreasing tendency extended to month 3 and 6.

Vocalization Response is Attenuated by the Presence of the Mother

The vocalization response during isolation at 3 and 6 months was compared to the vocalization response in the free play test with the sedated mother at 3 and 6 months. The number of vocalizations/minute was analyzed with a 2×2 repeated measures ANOVA for age (3 vs. 6 months) and condition (with or without mother). This analysis revealed significant main effects for age (F(1,20) = 21.827, p < 0.001) and condition (F(1,20) = 37.09, p < 0.001) and a significant interaction between of age and condition (F(1,20) = 4.87, p < 0.05). Paired t-tests revealed significantly lower vocalization during free play than isolation at both 3 (t (20) = 4.968, p < 0.001) and 6 (t (20) = 4.39, p < 0.001) months of age.

Approach to Sedated Mother

We next assessed the “active” maternal contact response of infants in the free play test at both 3 and 6 months of age by comparing time in physical contact with the mother. Because many of the animals had maximal or near maximal time spent on the mother the distribution had a strong negative skew (3 month skew = −1.037, 6 month skew = −1.356, Std error of skew = .501) and normalization attempts would be relatively ineffective because ceiling effects led to truncated maximal values. We therefore performed a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare time on mother at 3 and 6 months of age. This revealed no significant difference between ages Z = −0.469, p = .639, indicating that unlike the vocalization response the time in physical contact did not vary as a function of age across the 3 and 6 month assessments.

Development of Locomotor Response Across Development

Finally we assessed changes in locomotor activity across development by comparing the number of seconds engaged in locomotion at 3 and 6 months of age in both the separation and free play tests. Repeated measures ANOVAs revealed no significant effect of age in either the separation (F(1,20) = 0.067, p > 0.05) or free play tests between 3 and 6 months of age suggesting a stable developmental pattern of locomotion.

Intrasubject Stability of Measures Across Development

In order to assess stability of the separation response, active maternal contact and locomotor activity across development we conducted bivariate correlations between the vocalization responses and activity measures in the Brazelton tests (Table 1) and between separation vocalizations, free play vocalizations, and the mean neonatal vocalization and locomotor measures across the first month of life (Table 2). Vocalization rate and locomotor activity were generally well correlated within measures but correlated poorly between measures. For example, coo vocalizations on day 14, day 21 and day 30 are significantly correlated with each other and activity on day 7, day 14, and day 30 are also significantly correlated with each other. However no significant correlations were found between vocalizations and activity across the first month of life (all p > 0.05).

Table One.

Correlation among vocalizations and locomotion measures during the first month

| COO -7 | COO-14 | COO-21 | COQ-30 | LOCO-7 | LOCO-14 | LOCO-21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COO-14 | 0.321 | ||||||

| COO-21 | 0.257 | 0.923** | |||||

| C00-30 | 0.287 | 0.857** | 0.893** | ||||

| LOCO-7 | 0.227 | −0.292 | −0.351 | −0.221 | |||

| LOCO-14 | −0.029 | 0.156 | 0.083 | 0.189 | 0.706** | ||

| LOCO-21 | 0.004 | 0.289 | 0.386 | 0.359 | 0.276 | 0.422 | |

| LOCO-3Q | −0.024 | −0.011 | −0.094 | 0.201 | 0.632** | 0.538* | 0.226 |

p<.05

p<.01

Table Two.

Correlation among vocalizations and locomotion measures at the first, third and sixth months In Brazelton, separation and free play conditions.

| BRAZ COO 1M |

SEP COO 3M |

SEP COO 6M |

FP COO 3M |

FP COO 6M |

BRAZ LOCO 1M |

SEP LOCO 3M |

SEP LOCO 6M |

FP LOCO 3M |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEP COO 3M | 0.144 | ||||||||

| SEP COO 6M | −0.070 | 0.660** | |||||||

| FP C00 3M | 0.152 | 0.267 | 0.424 | ||||||

| FP C00 6M | 0.205 | 0.521* | 0.801** | 0.415 | |||||

| BRAZ LOCO 1M | 0.059 | −0.587* | −0.477 | −0.262 | −0.089 | ||||

| SEP LOCO 3M | −0.053 | −0.397 | −0.547* | −0.328 | −0.181 | 0.534* | |||

| SEP LOCO 6M | 0.132 | −0.275 | −0.488* | −0.111 | −0.219 | 0.372 | 0.605** | ||

| FP LOCO 3M | −0.123 | −0.361 | −0.430 | −0.039 | −0.370 | 0.131 | 0.137 | 0.063 | |

| FP LOCO 6M | −0.046 | −0.504* | −0.619** | −0.333 | −0.587** | 0.335 | 0.216 | 0.093 | 0.863** |

p<.05

p<.01

Cross correlations between mean locomotor and vocalization responses during the first month of life and these measures at 3 and 6 months of age are displayed in Table 2. Between 3 and 6 months of age, most measures were reasonably well correlated with themselves across time (r values between .4 and .9), with all but coo during free play being significantly correlated between 3 and 6 months tests. It is also evident from Table 2 that many of the measures were correlated with other measures and this relationship among variables becomes stronger with age. In particular the correlation between separation coos and free play coos increases between 3 and 6 months of age (see fig 4). We also compared the maternal contact time to vocalization frequency during both the separation and free play assessments at the three and six month time points. Because the contact data were not normally distributed we performed a median split on the data at each time point and grouped data into high and low contact groups. We then used multivariate ANOVAS to compare the high and low contact groups on vocalization frequency in separation and free play tests. This analysis revealed that the high and low contact groups did not differ in vocalization frequency in either test condition at 3 months (p’s >.6), but at 6 months a significant difference was found in separation vocalizations F(1, 20) = 4.49, p <.05 but in the free play test contact time was not significantly different, F (1, 20) = 2.96, p = .12 (see Figure 3). These data indicate that inter-subject differences in maternal motivation are stronger at 6 than 3 months of age.

Co-development of motor system and separation responses

Finally in order to assess the potential relationship between locomotor activity and separation response across development, we conducted correlations between activity measures (Brazelton activity score, seconds locomoting in free play and separation tests) and maternal proximity seeking behavior in the separation and free play tests. Results indicated that early indices of locomotor development were significantly correlated with vocalization and locomotor activity during separation at 3 months but the relationship between early locomotor activity and the separation response at 6 months of life was not sustained (Table 2). However a significant relationship was found between locomotor activity during the 3 month separation test and coo frequency at the 6 month separation test. These results suggest a moderate relationship between locomotor development and response to maternal separation but it is not stable across long periods of development.

Discussion

The present study investigated the developmental pattern of the separation response behavior of rhesus infants across the first 6 months of life. The rate of coo vocalizations during maternal separation increased from day 7 to day 14 and then successively decreased across test days 20, 30, 90, and 180. The present result is similar to previous studies (Brunelli & Hofer, 1996; Hofer et al., 2001; Kalin & Shelton, 1998). Taken together these results indicate a clear pattern of reduced intensity of the separation response across infancy. Although we do not have data on the effect of the mother across the first month of life, our findings from 3 and 6 months of age that the coo rate was significantly reduced when testing occurred in the presence of a sedated mother is an indication that the distress response was at least partially driven by separation from the mother. Taken together these data are consistent with our hypothesized relationship between motivation for maternal proximity and maternal dependence prior to weaning. Distress at separation from the mother declines as infants’ survival becomes less dependent on maternal interaction. While there are clearly factors that confound with development in the present study (i.e. repeated assessments, varying methods used to collect these data) we believe that the most parsimonious explanation and the one most consistent with other observations is a developmental progression toward diminished motivation to protest during bouts of maternal separation.

Although the rate of separation vocalizations declined across development, the change in the active proximity seeking response was less clear. There was no difference in overall time spent with the mother during the 40 minute free play test between 3 and 6 months of age. Because we do not have data on this response prior to 3 months of age, it is impossible to say whether there would have been much decline between the first and third month of life in this response, although we note that many of the subjects spent the entire test session in contact with the mother. The fact that there was no change in active contact seeking response while there was a clear reduction in the passive separation response suggests that these are dissociable responses and are mediated by independent biological processes with different developmental trajectories. However this interpretation is complicated by the finding that the vocalization frequency is positively correlated with maternal contact time. It appears that although separation vocalization rate does decline across development and the maternal contact time does not change, those with the highest rates of vocalization also spent the most amount of time in physical contact with the mother. Taken together this suggests that these processes may relate to a common affective response with elements that are dissociable across development.

A second major finding from the present study is that on several different behavioral assays we found a significant negative relationship between locomotor activity and separation response. For example the mean Brazelton locomotor development index across the first month of life was negatively correlated with isolation vocalizations at 3 months of age, and locomotor activity during separation at both 3 and 6 months during the 6 month free play test were negatively correlated with isolation vocalizations at 6 months of age. Finally we also observed a negative relationship between time on mom and locomotor activity in the free play test itself. This later finding is less surprising as locomotor activity would tend to drive the subjects away from the mother who was sedated and stationary. Nonetheless these findings suggest that development of locomotor capabilities, or the desire to engage in locomotor activity may go hand in hand with a reduction in motivation to maintain maternal proximity. This may indicate that locomotor development is an index of infant independence, though it also may suggest that intense separation distress hampers locomotor exploroation (Hinde & Spencer-Booth, 1970; Kalin & Shelton, 1989, 1998). Similar observations have been made in studies of humans although these studies have focused on the relationship of prenatal motor activity to postnatal separation response. However, the mechanism underlying this phenomenon and its biological meaning is not clear and further studies are needed.

Our third main finding in this study is that stable inter-individual differences in maternal motivation become increasingly clear between 3 and 6 months of age. Of the three measures of maternal motivation (separation vocalization; free play vocalization; physical contact with sedated mother) we obtained at 3 and 6 months of age none of them were significantly correlated at 3 months of age but all three were correlated with each other at 6 months of age. Moreover, it appears vocalizations from the same individuals become increasingly correlated across contexts between 3 and 6 months of age. The relationship between maternal contact and vocalizations at 6 months of age reveals a very interesting pattern. In both the free play and the separation test there was a group of subjects who vocalized at a very low rate and these were the same subjects who spent relatively little time in physical contact with the mother in the free play test. This confluence of results is strong indication that both separation vocalization and maternal contact are tapping into the same motivational construct, though they may be under slightly different developmental trajectories.

Human studies likewise have shown strong correlation between separation distress and proximity seeking behaviors in infants and toddlers (Kochanska, 2001; Kochanska & Coy, 2002). Importantly, however, meaningful and stable individual differences begin to emerge at approximately 14 months of age in humans (Kochanska, 2001; Kochanska & Coy, 2002). This timeline coincides with what is often a typical age of weaning in western societies (Konner, 2010), and the earliest diagnosis of separation anxiety (Beesdo et al., 2009). Therefore in both human and nonhuman primates, data indicate that stability in inter-individual responding to separation emerges developmentally in the late infancy period when the normative motivation for maternal proximity is in decline, and infants begin to develop independence in locomotor and ingestive behaviors. In the context of human SA, pathological responses to separation may be a consequence of global developmental delay or a mismatch in developmental changes in motivation to maintain maternal contact and maturation of other systems such as locomotion. Future human based studies should make a direct comparison of the relationship between separation anxiety and developmental competence in multiple domains to try to flush out the directional relationship between these variables if a relationship is found.

Although our data are compelling, there are several limitations to this study. First, our developmental analysis was compounded with novelty of experience. The reduction in vocalization frequency across repeated tests could have been a result of either maturation response or habituation to repeated experiences. While this confound is unavoidable in a longitudinal developmental design like this, a cross sectional control group with initial testing at different developmental ages could help dissociate maturation from habituation effects. Second, our separation responses included not only separation from the mother but also removal from the home cage and social environment. While this procedure enabled us to focus on behavior of thie infant without other distracting stimuli, it did introduce another level of complexity. Finally we performed many comparisons in this study and because of the relatively exploratory nature of this study we did not correct for multiple comparisons. It is possible therefore that some of the significant effects in this manuscript are spurious. Significant findings will need to be replicated in future studies.

In sum, our data suggest that in infant rhesus monkeys, as in rodents, the motivation to maintain maternal proximity undergoes a gradual transition across development. Soon after birth separation from the mother induces a modest separation response. This response then increases across the first week and then gradually declines across the first 6 months of life. The developmental decline in proximity seeking may be related to competence in other developmental domains like locomotor activity and stable inter-individual differences become increasingly clear in later stages of the normative developmental decline.

Acknowledgements

The work presented here was supported entirely by the intramural research program of the National Institutes of Health, NIMH. The authors wish to thank the veterinary and animal care staff of the NIH animal facility in Poolesville

References

- Ainsworth MD. Patterns of infant-mother attachments: antecedents and effects on development. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1985;61(9):771–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr RG. The normal crying curve: what do we really know? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990;32(4):356–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1990.tb16949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(3):483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman CM. Mother-infant relationships among free-ranging rhesus monkeys on Cayo Santiago: A comparison with captive pairs. Animal Behaviour. 1980;28(3):860–873. [Google Scholar]

- Bethea CL, Streicher JM, Coleman K, Pau FK, Moessner R, Cameron JL. Anxious behavior and fenfluramine-induced prolactin secretion in young rhesus macaques with different alleles of the serotonin reuptake transporter polymorphism (5HTTLPR) Behav Genet. 2004;34(3):295–307. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000017873.61607.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. World Health Organisation monograph. 1952. Maternal Care and Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli SA, Hofer MA. Development of ultrasonic vocalization responses in genetically heterogeneous National Institute of Health (N:NIH) rats. II. Associations among variables and behaviors. Dev Psychobiol. 1996;29(6):517–528. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199609)29:6<517::AID-DEV4>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JL, Bacanu SA, Coleman K, Dahl RE, Devlin BJ, Rogers J, et al. Dissociating components of anxious behavior in young rhesus monkeys: A precursor to genetic studies. In: Gorman JM, editor. Fear & Anxiety: Benefits of Translational Research. American Psychiatric Press; Washington DC: 2003. pp. 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan JD, Smith EL, Altemus M, Scharf BA, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB, et al. Variable foraging demand rearing: sustained elevations in cisternal cerebrospinal fluid corticotropin-releasing factor concentrations in adult primates. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(3):200–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(3):729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA, Rubin KH. Predicting Social Wariness in Middle Childhood: The Moderating Roles of Child Care History, Maternal Personality and Maternal Behavior. Soc Dev. 2008;17(3):471–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Bornstein MH, Costigan KA, Pressman EK, Hahn CS, Painter K, et al. What does fetal movement predict about behavior during the first two years of life? Dev Psychobiol. 2002;40(4):358–371. doi: 10.1002/dev.10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel D, Matheny AP., Jr Genetic and environmental influences on a measure of infant attachment security. Twin Res. 2000;3(4):242–250. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Larson MC, Hertsgaard L, Harris ML, Brodersen L. The stressfulness of separation among nine-month-old infants: effects of social context variables and infant temperament. Child Dev. 1992;63(2):290–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow HF, Dodsworth RO, Harlow MK. Total social isolation in monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1965;54(1):90–97. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde RA, McGinnis L. Some factors influencing the effects of temporary mother-infant separation: some experiments with rhesus monkeys. Psychol Med. 1977;7(2):197–212. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700029275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde RA, Spencer-Booth Y. The behaviour of socially living rhesus monkeys in their first two and a half years. Anim Behav. 1967;15(1):169–196. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3472(67)80029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde RA, Spencer-Booth Y. Individual differences in the responses of rhesus monkeys to a period of separation from their mothers. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology. 1970;11:159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hinde RA, Spencer-Booth Y. Effects of brief separation from mother on rhesus monkeys. Science. 1971;173(992):111–118. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3992.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde RA, White LE. Dynamics of a relationship: rhesus mother-infant ventro-ventral contact. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1974;86(1):8–23. doi: 10.1037/h0035974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA. Hidden regulators in attachment, separation, and loss. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59(2-3):192–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA, Shair HN, Masmela JR, Brunelli SA. Developmental effects of selective breeding for an infantile trait: the rat pup ultrasonic isolation call. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;39(4):231–246. doi: 10.1002/dev.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA, Sullivan RM. Toward a Neurobiology of Attachment. In: Nelson CA, Luciana M, editors. Handbook of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. MIT Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2001. pp. 599–616. [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M, Chaki S. Separation-induced ultrasonic vocalization in rat pups: further pharmacological characterization. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82(4):652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Defensive behaviors in infant rhesus monkeys: environmental cues and neurochemical regulation. Science. 1989;243(4899):1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.2564702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Ontogeny and stability of separation and threat-induced defensive behaviors in rhesus monkeys during the first year of life. Am J Primatol. 1998;44(2):125–135. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1998)44:2<125::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Lynn DE. Opiate systems in mother and infant primates coordinate intimate contact during reunion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20(7):735–742. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Emotional development in children with different attachment histories: the first three years. Child Dev. 2001;72(2):474–490. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Coy KC. Child emotionality and maternal responsiveness as predictors of reunion behaviors in the strange situation: links mediated and unmediated by separation distress. Child Dev. 2002;73(1):228–240. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konner M. The Evolution of Childhood. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Developmental determinants of sensitivity and resistance to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(10):939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S, Franklin D, Gonzalez CA. Influence of social variables on the biobehavioral response to separation in rhesus monkey infants. Child Dev. 1984;55(4):1386–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S, Wiener SG, Coe CL, Bayart FE, Hayashi KT. Primate vocalization: a psychobiological approach. Child Dev. 1987;58(6):1408–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Tornatsky W, Vivian J. Advances in Pharmacological Science. Birkauser; Basel, Switzerland: 1991. Ethology and neuropharmacology: rodent ultrasounds; pp. 409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GD. Attachment differences in male and female infant monkeys. Child Dev. 1968;39(2):611–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Panksepp J. Brain substrates of infant-mother attachment: contributions of opioids, oxytocin, and norepinephrine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22(3):437–452. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noirot E. Ultrasounds in young rodents. II. Changes with age in albino rats. Anim Behav. 1968;16(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(68)90123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Nelson E, Bekkedal M. Brain systems for the mediation of social separation-distress and social-reward. Evolutionary antecedents and neuropeptide intermediaries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;807:78–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling JK, Winslow JT, O’Brien D, Gutman DA, Hoffman JM, Kilts CD. Neural correlates of maternal separation in rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(2):146–157. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00977-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Kreppner J, Sonuga-Barke E. Emanuel Miller Lecture: Attachment insecurity, disinhibited attachment, and attachment disorders: where do research findings leave the concepts? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(5):529–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ML, Moore CF, Suomi SJ, Champoux M. Laboratory assessment of temperament and environmental enrichment in rhesus monkey infants (Macaca mulatta) American Journal of Primatology. 1991;25(137-155) doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350250302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ML, Suomi SJ. Neurobehavioral assessment in rhesus monkey neonates (Macaca mulatta): developmental changes, behavioral stability, and early experience. Infant Behavior and Development. 1992;15:155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Singh M. Mother-infant separation in rhesus monkey living in natural environment. Primates. 1975;16(4):471–476. [Google Scholar]

- St James-Roberts I, Conroy S, Wilsher K. Stability and outcome of persistent infant crying. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21(3):411–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomi SJ. Mother–infant attachment, peer relationships, and the development of social networks in rhesus monkeys. Human Development. 2005;48:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E, Alberts JR, Cramer CP. Weaning in rats: II. Pup behavior patterns. Dev Psychobiol. 1990;23(6):495–510. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way BM, Taylor SE, Eisenberger NI. Variation in the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) is associated with dispositional and neural sensitivity to social rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(35):15079–15084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812612106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DE, Coleman K, Bacanu SA, Devlin BJ, Rogers J, Ryan ND, et al. Heritability of fearful-anxious endophenotypes in infant rhesus macaques: a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(4):284–291. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow JT, Insel TR. The infant rat separation paradigm: a novel test for novel anxiolytics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12(11):402–404. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90616-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeifman DM. An ethological analysis of human infant crying: answering Tinbergen’s four questions. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;39(4):265–285. doi: 10.1002/dev.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]