Abstract

Purpose

Radiation necrosis is a major complication of radiation therapy. We explore the features of radiation-induced brain necrosis in the rat, using multiple MRI approaches, including T1, T2, apparent diffusion constant (ADC), cerebral blood flow (CBF), magnetization transfer ratio (MTR), and amide proton transfer (APT) of endogenous mobile proteins and peptides.

Methods and Materials

Adult rats (Fischer 344; n = 15) were irradiated with a single, well-collimated X-ray beam (40 Gy; 10 × 10 mm2) in the left brain hemisphere. MRI was acquired on a 4.7 T animal scanner at ~25 weeks post-radiation. The MRI signals of necrotic cores and peri-necrotic regions were assessed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Histological evaluation was accomplished with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

Results

ADC and CBF MRI could separate peri-necrotic and contralateral normal brain tissue (p < 0.01 and < 0.05, respectively), while T1, T2, MTR, and APT could not. MRI signal intensities were significantly lower in the necrotic core than in normal brain for CBF (p < 0.001) and APT (p < 0.01), while insignificantly higher or lower for T1, T2, MTR, and ADC. Histological results demonstrated coagulative necrosis within the necrotic core, and reactive astrogliosis and vascular damage within the peri-necrotic region.

Conclusion

ADC and CBF are promising imaging biomarkers for identifying peri-necrotic regions, while CBF and APT are promising for identifying necrotic cores.

Keywords: Radiation necrosis, biomarker, APT imaging, molecular imaging, MRI

Introduction

Radiotherapy is a major treatment modality for benign and malignant brain tumors. However, radiation kills not only tumor cells, but also injures surrounding normal brain tissue, which may cause radiation necrosis in the months or years following therapy (1, 2). Radiation necrosis, which usually shows new or increased gadolinium (Gd) enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is irreversible and is characterized as treatment-induced cell death in endothelium and white matter necrosis. Patients with radiation necrosis may suffer from life-threatening complications of edema, severe neuropsychological symptoms, as well as cognitive decline. In particular, it has been reported that concurrent radiotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy for glioblastomas is associated with an increased incidence (20–30% of patients) of radiation-induced early changes within the first months after therapy (2, 3). This so-called pseudoprogression may be associated with the transiently increased permeability of the tumor vasculature from radiotherapy, and usually resolves spontaneously. Similar to radiation necrosis, pseudoprogression can mimic actual tumor progression, clinically and radiographically (4). This phenomenon represents a major diagnostic challenge in neuro-oncology, leading to an international effort to develop new response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas (3).

Surgical biopsy is still the gold standard for identifying either treatment effects (radiation necrosis, pseudoprogression) or tumor recurrence. However, the procedure is invasive and may induce severe complications, even death. Therefore, noninvasive imaging markers to accurately assess these different pathologies would have tremendous benefits for the quality of life of patients, and for optimization of treatment regimens. Several advanced MR techniques, including MR spectroscopy (5), dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (6), and diffusion tensor MRI (7), as well as nuclear medicine approaches (8), may be helpful in detecting radiation necrosis. Although promising, the results have been mixed. Currently, there is still no standard imaging modality available for differentiating tumor from treatment effects in the clinic.

Amide proton transfer (APT) imaging (9, 10) is a molecular MRI technique that provides contrast based on the amide protons of endogenous mobile proteins and peptides, such as those in the cytoplasm. Previous studies on pre-clinical animal models (11) and human subjects (12) have indicated that APT imaging characterizes high-grade gliomas as hyperintense lesions, since such tumors over-express proteins and peptides, compared to expression of these proteins and peptides in the normal brain and in low-grade tumors (13). Conversely, radiation-induced brain necrosis, such as parenchymal coagulative necrosis, is likely associated with a decreased content of mobile cytosolic proteins and peptides (2). Therefore, APT imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides may provide unique imaging features by which to separate radiation necrosis from gliomas (10). The purpose of this study is to quantitatively compare the APT imaging features of radiation necrosis with the appearance of these features on other MRI modalities, including T1, T2, magnetization transfer ratio (MTR), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and cerebral blood flow (CBF) sequences.

Methods and Materials

Radiation necrosis model

All experiments were conducted with the approval of the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. Fifteen adult rats (Fischer 344; male; 8–10 weeks; 200–250 g) were irradiated with a small animal radiation research platform (14). Briefly, anesthesia was induced with 4% isoflurane for about four min, followed by 2–2.5% isoflurane for maintenance. Rats were immobilized in a fixation device. Under the guidance of planar fluoroscopic imaging, a single, well-collimated X-ray beam was delivered, with a single dose of 40 Gy to a 10 × 10 mm2 region in the left brain hemisphere, and the right hemisphere received a negligible dose (<3% of the dose delivered).

MRI data acquisition

Imaging experiments were performed on a 4.7 T animal MRI system (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA), with an actively decoupled cross-coil setup of a 70 mm body coil for radiofrequency (RF) transmission and a 25 mm surface coil for signal reception. T2-weighted (T2w) images were first acquired using the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 3 s; echo time (TE) = 64 ms; 5 slices; thickness = 1.5 mm; field of view (FOV) = 42 × 32 mm2; matrix = 256 × 192; number of average (NA) = 2.

Then, a T1 map (inversion recovery; predelay = 3 s; TE = 30 ms; TI = 0.05–3.5 s; NA = 4), a T2 map (TR = 3 s; TE = 30–90 ms; NA = 4), and an ADC map (single-shot trace diffusion weighting; TR = 3 s; TE = 80 ms; b-values = 0–1000 s/mm2; NA = 8) were scanned. A CBF map was acquired using an arterial spin labeling (ASL) sequence (15), with 3 s labeling at a distance of 20 mm away from the imaging slice (TR = 6 s; TE = 28.6 ms, NA = 16). APT data were acquired using previously described methods (9, 10), with frequency-labeling offsets of ±3.5 ppm with respect to water. The imaging matrix was 64 × 64, FOV = 32 × 32 mm2, TR = 10 s, TE = 30 ms, NA = 16, and the slice thickness was 1.5 mm. Conventional MTR images were acquired that had the same experimental parameters as the APT scans, except that an RF saturation frequency offset of 10 ppm (2000 Hz at 4.7 T) was used.

Finally, T1-weighted (T1w) images and Gd-enhanced T1w images were acquired with scanning parameters of TR = 700 ms, TE = 10 ms, and NA = 10. The geometry and location of Gd-enhanced T1w images were similar to the T2w images.

Image analysis

Interactive Data Language (IDL, Research Systems, Inc., Boulder, CO, USA) was used to process all imaging data. The T1 map, T2 map, and ADC map were fitted, using the following equations: I = A + B exp(−TI/T1), I = I0 exp(−TE/T2), and I = I0 exp(−b ADC), respectively. The CBF map was reconstructed from images with and without labeling using previously described methods (15). The MTR map was obtained at an offset of 10 ppm, using the equation: MTR(10ppm) = 1 − Ssat(10ppm)/S0, where Ssat and S0 are the signal intensities with and without RF irradiation.

As described in our previous studies (9, 10), the APT-MRI signal was quantified by the MTR asymmetry at ±3.5 ppm with respect to the water signal:

where MTR′asym(3.5ppm) has a complicated origin (16) and APTR is the APT ratio. Notice that, according to Eq. (1), the MTRasym(3.5ppm) signal in the normal brain tissue may be negative, due to the asymmetry of the conventional MT effect with respect to the water resonance. We therefore refer to this as the APT-weighted (APTw) signal.

As described below, ADC maps clearly show that radiation necrosis consists of a hypointense necrotic core and a hyperintense peri-necrotic region. For quantitative analysis of MRI signal intensities, these co-registered ADC maps were used to define the regions of interest (ROIs). Namely, a necrotic periphery, with an approximately 10% higher ADC than the contralateral normal brain (thalamus), was defined as the peri-necrotic region, while the central region, with an approximately 10% lower ADC than the contralateral normal, was defined as the necrotic core. For each rat, these ROIs were transferred to identical sites on other MRI maps. Ventricles were excluded.

Histopathology evaluation

Rats were sacrificed after multi-modality MRI scanning and perfused and fixed through the left cardiac ventricle with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Brain samples were sectioned (10 μm thick), and histological sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Brain sections were analyzed using a light microscope at 10× ~ 200× magnification.

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, followed by multiple comparisons of the Tukey test, were applied to analyze statistical differences in MRI signal intensities in the necrotic core, the peri-necrotic region, and the contralateral normal brain. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS for Windows (Version 18, Chicago, IL). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

General results and conventional MRI features of radiation necrosis

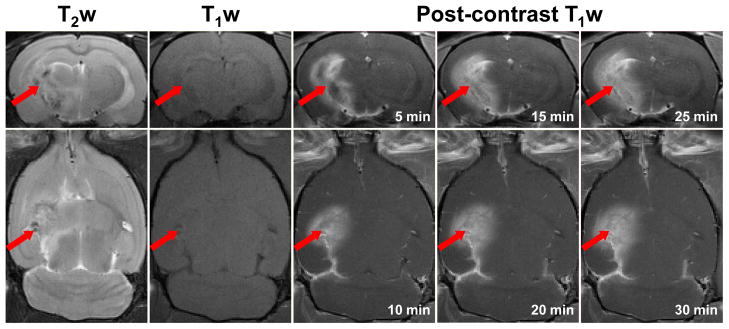

Beginning at around 22–24 weeks post-radiation in all rats, radiation necrosis (Fig. 1) was observed in the irradiated hemisphere, including the white matter, such as the fornix, the external capsule, the internal capsule, and the cerebral peduncle, and in the adjacent gray matter, such as the caudate putamen and the hypothalamus. T2w images showed high heterogeneity, with areas of high and low signals in the lesion. On the T1w images, the lesion was iso-intense to slightly hypointense, but the contrast was low. On the Gd-enhanced T1w images, the peripheral enhancement could be observed at five minutes post-contrast administration, but the enhancement was relatively homogenous subsequently. In addition, there were mild mass effects in the putamen and hypothalamus. These conventional MRI features of radiation necrosis in the animal model, consistent with those seen in human subjects, cannot be differentiated from the imaging features of brain tumor recurrence, such as an abnormality on T2w images, Gd enhancement on post-contrast T1w images, and mass effects (17).

Fig. 1.

Conventional MRI features of radiation necrosis in a rat (25 weeks post-radiation). T2w images show a heterogeneous lesion (arrow) in the irradiated hemisphere. T1w images show that the lesion is iso-intense or slightly hypointense. Contrast-enhanced T1w images show peripheral enhancement at the earliest time point (five min post-contrast) and relatively homogenous enhancement subsequently.

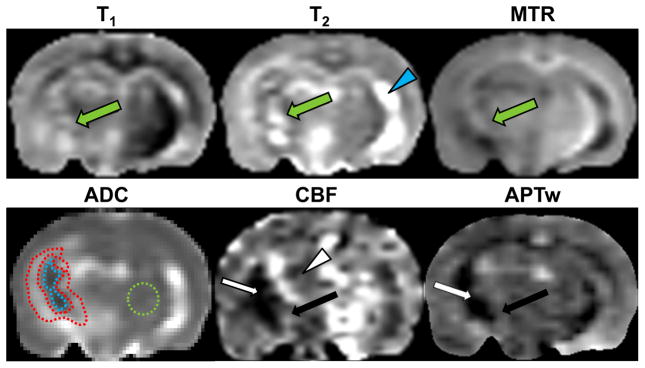

Multi-parametric MRI of radiation necrosis

Figure 2 shows one example of the multi-parametric MRI features of radiation necrosis in the rat model. The ADC, CBF, and APT maps demonstrated clear patterns inside the ipsilateral hemisphere. The ADC showed a necrotic core that was seemingly hypointense and a peri-necrotic region that was highly hyperintense. On the CBF map, it seemed that the entire irradiated hemisphere had a decreased CBF signal, compared to the contralateral normal brain. As far as the irradiated hemisphere is concerned, the lesion comprised a large hypointense necrotic core and a slightly hyperintense peri-necrotic region. Notably, the APTw image showed a necrotic core of hypointensity, compared to the contralateral normal brain. The peri-necrotic region that was hyperintense on ADC showed iso-intense to slightly hyperintense signal characteristics. Conversely, radiation necrosis had quite heterogeneous signal characteristics on the conventional T1 or T2 maps. On the MTR map, the signal intensities of radiation necrosis slightly decreased, especially in the regions of irradiated white matter tracts, such as the external capsule, the internal capsule, and the cerebral peduncle. No clear patterns were observed on the T1, T2, or MTR maps.

Fig. 2.

Multi-parametric MR images of radiation necrosis in a rat (26 weeks post-radiation). Radiation necrosis is heterogeneous on the T1 map, the T2 map, and the MTR map (green arrow). The ADC map shows a hypointense necrotic core and a hyperintense peri-necrotic region. On the CBF map, a large region of the ipsilateral hemisphere (white arrowhead) has reduced CBF signal. APTw imaging shows a hypointense necrotic core (white arrow), and an iso-intense or slightly hyperintense peri-necrotic region (black arrow). The display windows are: T2 map (0 to 100 ms); T1 map (0.5 to 2 s); MTR (0 to 50% of the bulk water intensity); ADC (0 to 2 × 10−9 m2/s); CBF (0 to 200 ml/100g/min); and MTRasym(3.5ppm) (−10% to 10% of the bulk water intensity). The very bright area (blue arrowhead) on the contralateral hemisphere on the T2 map is a ventricle. The ROIs used for quantitative analysis are drawn on the ADC map: necrotic core = encompassed by the dashed blue line; peri-necrotic region = encompassed by the dashed red lines; contralateral normal brain = encompassed by the dashed green circle.

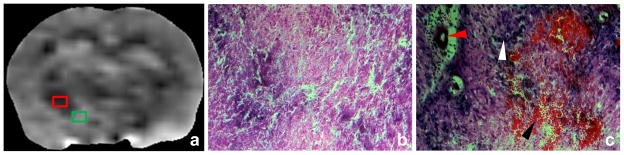

Histological evaluation

There were distinct histological changes within the necrotic lesion. Coagulative necrosis (the cardinal histological characteristic of radiation necrosis), together with vacuolation changes, were observed in the APTw-hypointense central zone (Fig. 3b). This region consisted mainly of the white matter tracts, such as the external capsule, the internal capsule, the cerebral peduncle, and the fornix. The periphery of radiation necrosis that covered the regions of the putamen and the cortex (Fig. 3c) presented complicated histological components, such as massive reactive astrogliosis, hypercellularity, thickening of vascular walls, vascular dilation, and hemorrhage. This region corresponded to the iso-intense or slightly hyperintense APTw imaging signal.

Fig. 3.

APTw image (a) and high-magnification (20×) H&E-stained images (b, c) of radiation necrosis in a rat (25 weeks post-radiation). The APTw-hypointense central region (red box) shows coagulative necrosis and vacuolation changes (b). The peri-necrotic region with an iso-intense or slightly hyperintense APTw signal (green box) corresponds to reactive astrogliosis (white arrowhead in c), dilated vessels with thickened vessel walls (red arrowhead), and hemorrhage (black arrowhead).

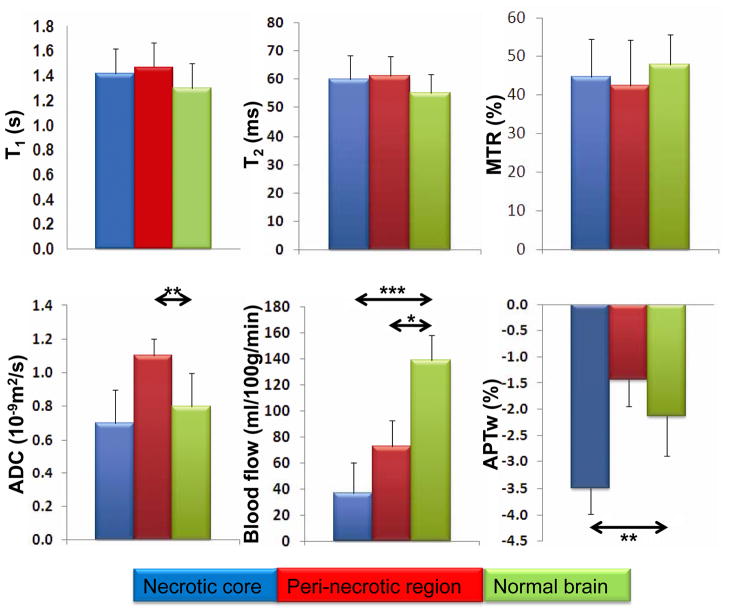

Quantitative analysis of radiation necrosis using multi-parametric MRI

Figure 4 shows the results of the quantitative, multi-parametric MRI comparison between the necrotic core, peri-necrotic region, and contralateral normal brain tissue for all rats (n = 15). There were no significant differences in MRI signal intensities between these regions on the T1, T2, and MTR maps. Significantly higher ADC values were found in the peri-necrotic region than in normal brain (1.07 ± 0.20 vs. 0.80 ± 0.05 μm2/ms; p < 0.01). Although the ADC values in the necrotic core trended to be lower, the difference between the necrotic core and normal brain was not significant (0.71 ± 0.08 vs. 0.80 ± 0.05 μm2/ms; p > 0.05). On the CBF map, significantly lower MRI signal intensities were observed in the necrotic core and peri-necrotic region compared to normal brain (36.9 ± 25.9 vs. 139.1 ± 81.2 ml/100g/min; p < 0.001, 72.5 ± 39.8 vs. 139.1 ± 81.2 ml/100g/min; p < 0.05). Finally, the APTw signal intensities of the necrotic core were significantly lower than those of the contralateral normal brain (−3.54% ± 1.05% vs. −2.09% ± 0.82%; p < 0.01). However, the APTw signal intensities of the peri-necrotic area and the contralateral normal brain were not significantly different (−1.31% ± 1.26% vs. −2.09% ± 0.82%; p > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Quantitative analysis of multi-parametric MRI of the necrotic core (blue bar), the peri-necrotic region (red bar), and the contralateral normal brain (green bar; n = 15). The definition of these ROIs is described in the text, and an example is given on the ADC map in Fig. 2. The APTw intensity is expressed as a percentage of the bulk water signal. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; not marked = not significant.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that several advanced MRI parameters (ADC, blood flow, and APT) are promising imaging biomarkers for the diagnosis of radiation necrosis in the preclinical model. APTw signal intensities were significantly lower in the necrotic core than in the contralateral normal brain (T1, T2, MTR, and ADC not significantly higher or lower). ADC signal intensities were significantly higher in the peri-necrotic region than in normal brain (T1, T2, MTR, and APTw not significantly higher or lower). CBF MRI (quantified by the ASL technique) could separate both the necrotic core and peri-necrotic region from normal brain, which seemed superior to APTw and the others. However, ASL is generally associated with a change of 1–2% in bulk water intensity (15) and APTw is associated with a change of 3–5% in bulk water intensity (12). Thus, APTw imaging should have a higher contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) than ASL. In a supplementary experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1e and Table 1e), we have further demonstrated that active glioma (hyperintense, compared to contralateral) and radiation necrosis (hypointense or iso-intense) exhibited opposite APT-MRI signals, which can be readily distinguished. Both ADC and APT seemed applicable to assessing radiation necrotic core and glioma. Unlike APT, however, both peri-necrotic regions and active tumors showed ADC hyperintensities and became indistinguishable from the ADC signals. Unfortunately, there was no significant difference in CBF between radiation necrosis and active tumor.

Histological evaluations demonstrated parenchymal coagulative necrosis in the necrotic core, and the reactive astrogliosis, vascular dilation, vessel wall thickening, or hemorrhage in the peri-necrotic region. The pathophysiological process of radiation necrosis has not been fully understood. Calvo et al. indicated that the damage to the endothelium, such as an enlarged endothelium, dilated vessels, and thickened vessel walls, are early events that precede the appearance of radiation necrosis. These changes, together with reactive astrogliosis, have been called a tissue injury unit (TIU), which precipitates a cascade of events leading to radiation necrosis (18). Typical histopathological features of radiation necrosis include parenchymal coagulative necrosis, reactive astrogliosis, hyalinization of vessel walls, as well as demyelination or axonal degeneration (1, 2, 7).

APT imaging provides a means by which to explore the molecular properties of cancer tissue in vivo at the protein level with endogenous contrast. Previous studies have shown that APT imaging can provide unique diagnostic information about brain cancer (11, 12) and prostate cancer (19). In contrast to cancer tissue, radiation necrosis, such as coagulative necrosis, is associated with the loss of mobile proteins and peptides in the cytoplasm. Therefore, APTw signal intensities should be lower in radiation necrosis than in cancer tissue. In addition to the amide concentration, the APT effect depends on the exchange rate between amide protons and bulk water protons (9, 10), which is associated with tissue pH. APT imaging has been used to identify the ischemic penumbra (APT hypointensity due to decreased pH) within the ischemia-induced hypo-perfusion region (20). In this study, we have shown, in a rat model, that the ipsilateral hemisphere affected by radiation necrosis displays a decreased CBF signal, compared to the contralateral normal brain, which may be attributed to radiation-induced vascular injury and swelling-induced pressure on the blood vessels. It is possible that decreased cerebral pH, due to ischemia, may contribute to the low APT signal in the necrotic lesion; however, further studies are required to confirm this.

Conclusions

Our preclinical results indicate that APTw images, based on endogenous contrast from mobile proteins and peptides, provide unique diagnostic information with which to characterize radiation necrosis at the protein level. As such, APT imaging has the potential to be an alternative imaging modality to improve the diagnostic accuracy of radiation necrosis in the clinic. It would be worthwhile to add this novel technique to the multi-parametric MRI exam for patients with suspected radiation necrosis versus tumor recurrence, especially considering the clinical implications of neurosurgery planning and the assessment of treatment effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Multi-parametric MR images of human glioblastoma xenografts (called GBM22) in a nude rat (100,000 tumor cells implanted, four weeks post-implantation). For more details about the tumor model, see Wang et al., J. Neuro-Oncology 2011 Sep 27. [Epub ahead of print] DOI: 10.1007/s11060-011-0719-x. Compared to the contralateral normal brain, the tumor (red arrow) is hyperintense on the T1, T2, ADC, and APTw maps, but hypointense on the MTR and CBF maps. The display windows are the same as in Fig. 2. The area encompassed by the red dashed line is the tumor ROI for quantitative analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Mary McAllister for editorial assistance. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (EB009112, EB009731, EB015032, and RR015241) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81128006).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kumar AJ, Leeds NE, Fuller GN, et al. Malignant gliomas: MR imaging spectrum of radiation therapy- and chemotherapy-induced necrosis of the brain after treatment. Radiology. 2000 Nov;217(2):377–84. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv36377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang I, Aghi MK. New advances that enable identification of glioblastoma recurrence. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009 Nov;6(11):648–57. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1963–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke JL, Chang S. Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse: Challenges in brain tumor imaging. Curr Neur Neurosci Rep. 2009;9:241–6. doi: 10.1007/s11910-009-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor JS, Langston JW, Reddick WE, et al. Clinical value of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy for differentiating recurrent or residual brain tumor from delayed cerebral necrosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996 Dec 1;36(5):1251–61. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozsunar Y, Mullins ME, Kwong K, et al. Glioma recurrence versus radiation necrosis? A pilot comparison of arterial spin-labeled, dynamic susceptibility contrast enhanced MRI, and FDG-PET imaging. Acad Radiol. 2010 Mar;17(3):282–90. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SL, Wu EX, Qiu DQ, et al. Longitudinal Diffusion Tensor Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Radiation-Induced White Matter Damage in a Rat Model. Cancer Research. 2009 Feb;69(3):1190–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen W. Clinical applications of PET in brain tumors. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1468–81. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.037689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou J, Payen J, Wilson DA, et al. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nature Med. 2003;9:1085–90. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Tryggestad E, Wen Z, et al. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nature Med. 2011;17:130–4. doi: 10.1038/nm.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J, Lal B, Wilson DA, et al. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2003 Dec;50(6):1120–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen Z, Hu S, Huang F, et al. MR imaging of high-grade brain tumors using endogenous protein and peptide-based contrast. Neuroimage. 2010 Jun;51(2):616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobbs SK, Shi G, Homer R, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided proteomics of human glioblastoma multiforme. J Magn Reson Imag. 2003;18:530–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong J, Armour E, Kazanzides P, et al. High-resolution, small animal radiation research platform with X-ray tomographic guidance capabilities. Int J Rad Oncol Bio Phys. 2008;71:1591–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DS, Detre JA, Leigh JS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of perfusion using spin inversion of arterial water. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Jan 1;89(1):212–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Blakeley JO, Hua J, et al. Practical data acquisition method for human brain tumor amide proton transfer (APT) imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:842–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers LR, Gutierrez J, Scarpace L, et al. Morphologic magnetic resonance imaging features of therapy-induced cerebral necrosis. J Neuro-Onc. 2011;101:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calvo W, Hopewell JW, Reinhold HS, et al. Time- and dose-related changes in the white matter of the rat brain after single doses of X rays. Br J Radiol. 1988 Nov;61(731):1043–52. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-61-731-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia G, Abaza R, Williams JD, et al. Amide proton transfer MR imaging of prostate cancer: a preliminary study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011 Mar;33(3):647–54. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun PZ, Zhou J, Sun W, et al. Detection of the ischemic penumbra using pH-weighted MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1129–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multi-parametric MR images of human glioblastoma xenografts (called GBM22) in a nude rat (100,000 tumor cells implanted, four weeks post-implantation). For more details about the tumor model, see Wang et al., J. Neuro-Oncology 2011 Sep 27. [Epub ahead of print] DOI: 10.1007/s11060-011-0719-x. Compared to the contralateral normal brain, the tumor (red arrow) is hyperintense on the T1, T2, ADC, and APTw maps, but hypointense on the MTR and CBF maps. The display windows are the same as in Fig. 2. The area encompassed by the red dashed line is the tumor ROI for quantitative analysis.