Abstract

Background and Purpose

The publication of the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS III) expanded the treatment time to thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke from 3 to 4.5 hours from symptom onset. The impact of the expanded time window on treatment rates has not been comprehensively evaluated in a population based study.

Methods

All patients suffering from an ischemic stroke presenting to an emergency department (ED) during calendar year 2005 in the 17 hospitals that compromise the large 1.3 million Greater Cincinnati / Northern Kentucky population were included in the analysis. Criteria for exclusion from thrombolytic therapy are analyzed retrospectively for both the standard and expanded time frames with varying door to needle times.

Results

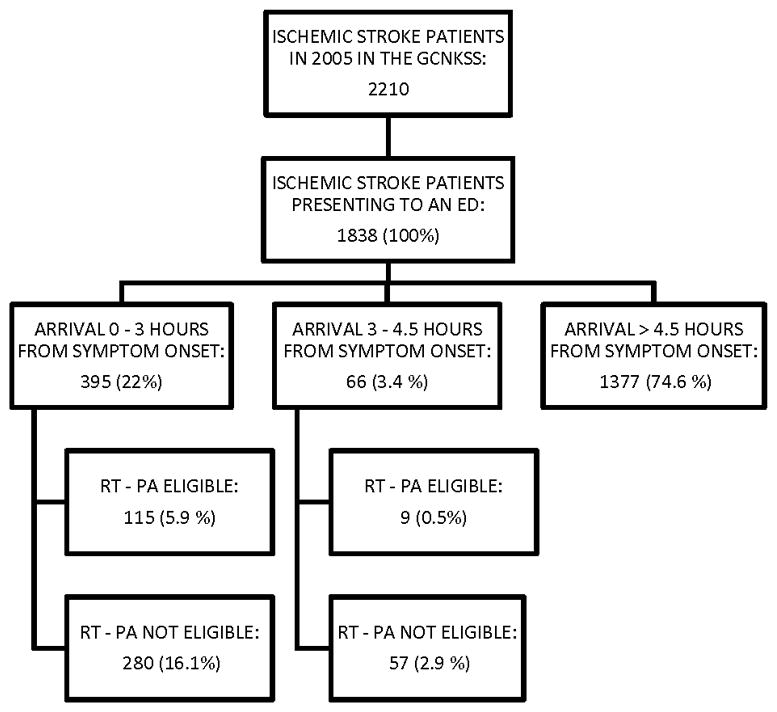

During the study period 1838 ischemic strokes presenting to an ED were identified. A small proportion of them arrived in the expanded time window (3.4%) compared to the standard time window (22%). Only 0.5% of those who arrived in this time frame met eligibility criteria for thrombolysis, compared to 5.9% using standard eligibility criteria in the standard timeframe. These results did not vary significantly by repeated analysis varying the door to needle time or the expanded time window’s exclusion criteria.

Conclusions

In reality, the expanded time window for thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke benefits few patients. If we are to improve rT-PA administration rates our focus should be on improving stroke awareness, transport to facilities with ability to administer thrombolysis, and familiarity of physicians with acute stroke treatment guidelines.

Keywords: Acute Stroke, ECASS, thrombolysis, stroke care, epidemiology

Introduction

Current U.S. guidelines for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke support early treatment with IV rt-PA for patients who meet the necessary criteria. Despite the clinical and economic benefits of giving rt-PA to ischemic stroke patients, few patients actually receive it. National estimates of rt-PA use range from 1.8% to 5.2%. (1, 2) Some of the efforts to improve rt-PA treatment rates have focused on the inclusion criteria for IV rt-PA, especially the time window from symptom onset (3–8) and the “door to needle time” (9–15).

A recent breakthrough regarding the time window for IV rt-PA use was reported by the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS III), which found that IV rt-PA was beneficial to selected patients up to 4.5 hours from stroke onset, thus expanding the time window from the previous guideline of 3 hours. However, the expanded time window included four new exclusion criteria that are stricter than the current criteria used in the U.S: age > 80 years, initial NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) > 25, history of both diabetes and prior stroke, or any oral anticoagulant use (16). The AHA recently updated their 2007 stroke guidelines to include the ECASS III study findings (class I recommendation, level of evidence B) (17).

We sought to determine the potential impact of the extended time window on IV rt-PA treatment rates. Previous studies focused on this topic have found only marginal benefits, but these studies had significant limitations. They were either not population based (18) or analyzed time from stroke onset to presentation at treatment facilities as the only exclusion criteria to thrombolysis (19). A more comprehensive analysis including all current practice exclusion criteria is required.

Methods

The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky (GCNK) region includes two southern Ohio counties and three Northern Kentucky counties separated by the Ohio River. This region represents a biracial metropolitan population of 1.3 million. The proportion of African Americans and socioeconomic status indicators are similar to the United States population in general (Hispanics, however, at 1.1% of the GCNK population, are underrepresented, compared with the US as a whole at 12.5%.). Although residents of nearby counties seek care at the 17 acute care hospitals in the study region, only residents of the five study area counties are included as cases. This analysis consisted of strokes which occurred from 1/1/2005 to 12/31/2005.

Briefly, study nurses reviewed the medical records of all patients with ICD-9 codes 430–436 as primary or secondary discharge diagnoses from the 17 acute-care hospitals in the study region. Strokes not found by this hospital ascertainment method were ascertained by monitoring all stroke-related visits to the nine local public health clinics, seven hospital-based outpatient clinics, and five county coroners’ offices. Further monitoring was performed by examining the records of potential stroke cases in a random sample of 51 of 832 primary care physicians’ offices and 26 of 126 nursing homes in the GCNK region. Sampling was necessary given the large number of both physician offices and nursing homes in the area. All events were cross-checked within and between sources to prevent double counting. IRB approval was obtained at each participating study site during all study periods. Further details on the methodology for screening cases has been described elsewhere. (20)

Once a potential case was identified, a study nurse abstracted data regarding the patient’s demographics and the stroke event from the medical record onto forms specifically designed for the study. Abstracted information and all available neuroimaging were then reviewed by a study physician, who made a final determination as to whether the patient met the case definition of acute stroke. The events were classified as ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, intracerebral hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage, according to definitions adapted from the Classification of Cerebrovascular Diseases III.(21)

Only ischemic stroke patients who presented to an emergency department (ED) within the study region were included in this analysis. Eligibility was determined based on prospectively collected symptoms and retrospectively abstracted clinical data, not whether thrombolysis was actually prescribed. Eligibility for rt-PA administration among patients presenting between 3 to 4.5 hours from symptom onset was defined in two ways: The first definition mirrors standard U.S. 2007 guidelines (22) (see Table 1). For the purposes of this analysis, we considered patients with minor symptoms (NIHSS < 5) upon arrival to the ED and those with a positive history of aneurysm, AVM, or brain tumor, as ineligible for IV rt-PA. The second definition for eligibility incorporated the ECASS 3 exclusion criteria (16) (Table 1), in addition to the first definition of eligibility. Patients with rapidly improving symptoms may be excluded from thrombolytic therapy in clinical practice. Due to the retrospective nature of our study and limitations of chart documentation, we were unable to identify this group of patients, therefore “rapidly improving symptoms” was not an exclusion in our analysis. We sought to determine the proportion of cases in our population eligible for treatment with IV rt-PA in the extended time window using each of these definitions.

Table 1.

Eligibility for Rt-PA within a Population for Ischemic Stroke Patients Who Arrived 0 to 3 hours or 3 to 4.5 hours after Symptom Onset.

| 2007 AHA Guidelines Exclusion Criteria | Time From Symptom Onset to ED Arrival | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 3 hours N=395 (22.0%) |

3 to 4.5 hours N=66 (3.4%) |

|

| minor symptoms (NIHSS<5) | 208 (11.5%) | 40 (2.1%) |

| SBP > 185 mm Hg or DBP > 110 mm Hg | 61 (3.2%) | 7 (0.4%) |

| stroke / (head trauma) in previous 3 months | 20 (2.6%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| INR >1.7, | 26 (2.1%) | 4 (0.2%) |

| aPTT value >40 | 22 (1.1%) | 7 (0.4%) |

| seizure in acute setting | 13 (0.7%) | 4 (0.2%) |

| major surgery in preceding 14 days | 11 (0.6%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| previous intracranial hemorrhage | 9 (0.5%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| aneurysm | 7 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| platelet count < 100,000 mm3 | 5 (0.3%) | 2 (0.1%) |

| myocardial infarction in previous 3 months | 2 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| GI / urinary tract hemorrhage in previous 21 days | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| serum glucose < 50 mg/dl | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| brain tumor | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| AVM | 0 0%) | 0 (0%) |

| active bleeding / acute trauma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| non compressible arterial puncture in previous 7 days | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| ECASS 3 Exclusion Criteria | ||

| age > 80 | 15 (0.8%) | |

| history of both diabetes and prior stroke | 3 (0.2%) | |

| any oral anticoagulant use or heparin use with aPTT value > 40 | 2 (0.1%) | |

| NIHSS > 25 | 2 (0.1%) | |

| Eligibility - Standard Criteria | 115 (5.9%) | 14 (0.7%) |

| Eligibility - ECASS 3 criteria | 9 (0.5%) | |

Data presented as raw n (weighted % of the 1838 strokes)

Each criteria is not mutually exclusive

Using time from symptom onset to arrival to the ED may not be the best criterion for determining eligibility for rt-PA treatment, as it may not account for the time to get a patient evaluated, imaged, interviewed, and prepared for acute thrombolysis. In addition to onset-to-arrival criteria, current guidelines recommend a “door-to-needle time” of ≤60 minutes. Therefore, a patient would need to arrive at the hospital within 2 hours to receive rt-PA within 3 hours from symptom onset (standard criteria), and would need to arrive within 3.5 hours to be eligible to receive rt-PA within 4.5 hours of onset (ECASS-3 criteria). Therefore we evaluated the impact of various door-to-needle times on the proportion of eligible cases.

Data were managed and analyzed using SAS® versions 8.02 and 9.2, respectively (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Percentages were obtained by including the sampling weights in all estimates as dictated by the study design. A weight of one was used for all cases except for those ascertained only through screening of a subset of physician’s offices (weight 831/51) and nursing homes (weight 126/26) in our region. Values are reported as raw counts with associated weighted percentages.

Results

During the study period, 2210 ischemic strokes in patients ≥18 years of age were identified, of which 1838 presented to an ED. The remainder 372 patients presented to other sites, such as primary care offices or nursing homes, or were hospitalized at the time of their stroke. These patients were excluded from this analysis. Demographics of the overall ischemic stroke population, and ischemic stroke patients arriving early after symptom onset are presented in Table 2. The elapsed time from symptom onset (or “time last seen normal” for strokes for which exact time of onset was not known) to arrival at the ED was greater than 4.5 hours for 1377 (74.6%) of the 1838 ED cases; 395 (22.0%) arrived in less than 3 hours from symptom onset; and 66 (3.4%) arrived in the 3- to 4.5-hour range (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Patient Demographics and Time from Symptom Onset.

| < 3 hours N = 395 |

3 – 4.5 hours N = 66 |

> 4.5 hours N = 1377 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 69.0 (1.3) | 68.1 (1.8) | 69.9 (0.4) |

| Female | 219 (55.0%) | 37 (56.1%) | 785 (58.8%) |

| White | 305 (75.3%) | 52 (78.8%) | 1029 (74.9%) |

| African American | 89 (24.5%) | 14 (21.2%) | 338 (24.4%) |

| Median baseline NIHSS | 4.0 (2, 12) | 3.5 (2, 8) | 3.0 (2, 6) |

| Median baseline mRS | 2 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 2) | 2 (0, 3) |

Data presented as weighted mean (weighted standard error), raw n (weighted %) or weighted median (weighted 25th, 75th percentiles)

Figure 1.

Eligibility for rT- PA and hospital arrival times.

Data presented as raw n (weighted % of the 1838 strokes).

According to standard eligibility for rt-PA criteria, 115 of the 395 who arrived within 3 hours of onset (5.9% of the 1838 ED cases) were eligible for rt-PA. With the expansion of the onset-to-arrival time window to 4.5 hours, an additional 9 patients (0.5% of the 1838 ED cases) would have been eligible based on ECASS-III criteria.

Contraindications to rt-PA administration for those who arrived to the ED within 3 hours and between 3 and 4.5 hours after symptom onset are listed in Table 1. The most frequent reason for non-treatment with rt-PA was mild stroke severity (defined as an initial NIHSSS <5); 208 of the 395 patients who presented within 3 hours, and 40 of the 66 who presented between 3 and 4.5 hours. In addition, the ECASS III criterion that requires a patient to be younger than 80 years would result in the exclusion of 15 of the 66 who presented in the expanded time window. Applying standard criteria, rather than the ECASS III criteria, to the expanded time window would have allowed 5 more patients (for a total of 14 patients, 0.8% of the 1838 ED cases) to be eligible for treatment with rt-PA.

When a door-to-needle time of 30 minutes was added as a criterion, which effectively reduces the onset-to-arrival window to < 2.5 hours for the standard eligibility criteria and reduces the expanded window for ECASS III criteria to 2.5–4 hours, the number of cases eligible for rt-PA was reduced from 115 to 108 (5.6%) and from 9 to 8 (0.4%), respectively. With a door-to-needle requirement of 60 minutes (the current national guideline recommendation), the number of standard-criteria cases (presented within 2 hours of onset) eligible for rt-PA was further reduced to 99 (5.4%), but it increased to 11 (0.6%) for ECASS-criteria patients (presented 2–3.5 hours after onset). This is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number (weighted %) of Patients Eligible for rt-PA using Standard Criteria and Expanded ECASS 3 Time Window/Criteria, Calculated Varying Treatment Time Assumptions. (N=1838 adult ischemic strokes presenting to ED).

| Treatment Time | Door-to-Needle time < 0 (Theoretical) | Door-to-Needle time ≤ 30 min | Door-to-Needle time ≤ 60 min* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from Sx Onset | 0–3 Hours | 3–4.5 Hours | 0–2.5 Hours | 2.5 – 4 Hours | 0–2 Hours | 2–3.5 Hours |

| Eligibility Criteria | standard | ECASS | standard | ECASS | standard | ECASS |

| Eligible for Rt-PA | 115 [5.9%] | 9 [0.5%] | 108 [5.6%] | 8 [0.4%] | 99 [5.1%] | 11 [0.6%] |

Data presented as raw n (weighted % of the 1838 strokes)

Current national guideline recommendation (23)

Discussion

Despite the promise of an extended time window to 4.5 hours from symptom onset for IV rt-PA administration, few additional ischemic stroke patients (an additional 0.5%) would have been eligible for treatment within our study population. This is in part due to the additional exclusion criteria described in the ECASS III trial, which exclude a significant portion of stroke patients, especially those over age 80, which represent 22.7% of those who arrived between 3 and 4.5 hours. This is in accordance to results obtained in previous studies (18, 19).

Several studies have found a potential benefit of IV rt-PA treatment after 3 hours from symptom onset without the additional exclusion criteria delineated in the ECASS III trial (24, 25). Unfortunately, analysis using the standard eligibility criteria on the 3–4.5 hour group still revealed minimal improvement in treatment rates. Only an additional 0.7% of patients would have been eligible for treatment.

The most important reason why more patients are not eligible in the extended time window is that patients tend not to arrive in the “acute but > 3 hours” time frame. In our population, 22.0% of patients arrived to the ED within three hours of onset, but only 3.4% arrived in the 3–4.5 time frame. This finding has been demonstrated in multiple other studies, some of which were also population-based(12, 19, 26, 27). Ischemic stroke patients tend to arrive either very early (< 2 hours) or quite late or with unknown onset times (wakeup or found down). Therefore, expecting treatment rates to increase purely by broadening the time window will not likely be successful. Greater efforts are needed to improve the public’s awareness of stroke warning signs and encouraging plans to seek emergency help when symptoms occur.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the extended time window did not substantially improve the eligibility for patients arriving later within the three hour window, nor did varying the treatment time from 60 minutes to 0 minutes. This does not imply, however, that door-to-needle time is not an important target for quality improvement. While varying the treatment times under one hour did not make a significant difference, many experienced stroke centers have difficulty achieving a one hour door-to-needle time, and there are many more patients that are missed altogether or have much longer delays in treatment. In fact, keeping the door-to-needle time as an important quality indicator of stroke centers may be even more important now with an extended time window, as physicians tend to respond to time deadlines. Recently, Schwamm et al. found that within a large quality improvement dataset among 30,000+ patients treated with rt-PA, time of arrival after onset was inversely proportional to the door-to-needle time (28), i.e., the earlier the patient arrived, the longer it took to get treated. Given the strong association with time to treatment and good outcome, there is a potential that the extended time window could actually harm more than help.

Our study had limitations that need to be taken into consideration. First of all, retrospective studies rely on past documentation (time of stroke onset and eligibility criteria). In a similar way, we took a conservative approach and excluded from rt-PA treatment patients who had a low NIHSS (<5), abnormal glucose and blood pressure levels, and a positive history of aneurysm, AVM, or brain tumor, all of which are not considered absolute exclusion criteria in clinical practice and guidelines. Also, we were unable to exclude from thrombolysis those patients with rapidly improving symptoms. This might lead to an overestimation of the patients eligible for thrombolysis. However, that is potentially counterbalanced, to some degree, by the underestimation of eligibility for those patients with an NIHSS < 5 but who present with significant or disabling symptoms. Similarly, we did not include in our analysis the patients who were already hospitalized at the time of their stroke. They were excluded because very few patients who present in this setting receive thrombolytics (N = 4; 5.5 % of all IV thrombolytics prescribed in our population during 2005) and the documentation regarding these events is generally not as detailed as the one provided in the ED. Finally, our analysis was performed in 2005, before the publication of the ECASS III or the SITS – ISTR (29) studies endorsing treatment up to 4.5 hours from symptom onset. Since our study did not determine eligibility based on thrombolysis administered by the treating physician but rather analyzed specific clinical and patient level data, we don’t expect this to influence our findings significantly. We can’t however, rule out changes following the publication of the updated guidelines that may lead to more patients being eligible for thrombolysis, such as increased timely transport of stroke patients in the expanded time window to emergency rooms.

In summary, IV rt-PA is of benefit to patients with acute ischemic stroke who present in the 3 to 4.5 hour window, albeit to a small percentage of all ischemic stroke patients. Care should be taken not to delay treatment due to the new expanded time window. Even though reducing the door to needle time did not increase the number of patients eligible for thrombolysis, reducing this time leads to improved patient outcomes and remains an important quality control measure. If we are to improve rt-PA administration rates, future health care resources should be focused on improving stroke awareness, transport to facilities with ability to administer rt-PA,(9–11, 13), and physician awareness of rt-PA administration guidelines (30), rather than expanding the treatment time window (31).

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

Funded by the NIH, NINDS Division. NIH NINDS R01 NS30678 and P50 NS044283-09.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests / disclosures

The following authors receive research support from the NIH: P. Khatri, D. Kleindorfer, O. Adeoye, B.M. Kissela, K. Alwell, C.J. Moomaw, and J.C. Khoury.

Dr. Pooja Khatri receives research support and travel support as an unpaid consultant from Genentech, also receives research support from Penumbra as PI of THERAPY Trial.

Dr. Kleindorfer and Dr. Adeoye are members of the speaker’s bureau, Genentech.

Dr. Kissela receives research support from Nexstium, he also receives honoraria from Allergan and Reata pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Flaherty receives honoraria from Boehringer – Ingelheim.

References

- 1.Kleindorfer D, Lindsell CJ, Brass L, Koroshetz W, Broderick JP. National US estimates of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator use: ICD-9 codes substantially underestimate. Stroke. 2008;39:924–928. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, Kleindorfer D. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator use for ischemic stroke in the united states: A doubling of treatment rates over the course of 5 years. Stroke. 2011;42:1952–1955. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saver JL, Gornbein J, Grotta J, Liebeskind D, Lutsep H, Schwamm L, et al. Number needed to treat to benefit and to harm for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator therapy in the 3- to 4.5-hour window: Joint outcome table analysis of the ECASS 3 trial. Stroke. 2009;40:2433–2437. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringleb PA, Schellinger PD, Schranz C, Hacke W. Thrombolytic therapy within 3 to 6 hours after onset of ischemic stroke: Useful or harmful? Stroke. 2002;33:1437–1441. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000015555.21285.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: A metaanalysis. Stroke. 2009;40:2438–2441. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.552547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacke W, Ringleb P, Stingele R. How did the results of ECASS II influence clinical practice of treatment of acute stroke. Rev Neurol. 1999;29:638–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis S, Donnan G. The ECASS III results and the tPA paradox. Int J Stroke. 2009;4:17–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bluhmki E, Chamorro A, Davalos A, Machnig T, Sauce C, Wahlgren N, et al. Stroke treatment with alteplase given 3.0–4.5 h after onset of acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS III): Additional outcomes and subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adeoye O, Lindsell C, Broderick J, Alwell K, Jauch E, Moomaw CJ, et al. Emergency medical services use by stroke patients: A population-based study. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleindorfer D, Khoury J, Broderick JP, Rademacher E, Woo D, Flaherty ML, et al. Temporal trends in public awareness of stroke: Warning signs, risk factors, and treatment. Stroke. 2009;40:2502–2506. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleindorfer D, Miller R, Sailor-Smith S, Moomaw CJ, Khoury J, Frankel M. The challenges of community-based research: The beauty shop stroke education project. Stroke. 2008;39:2331–2335. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleindorfer DO, Broderick JP, Khoury J, Flaherty ML, Woo D, Alwell K, et al. Emergency department arrival times after acute ischemic stroke during the 1990s. Neurocrit Care. 2007;7:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s12028-007-0029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleindorfer DO, Lindsell CJ, Broderick JP, Flaherty ML, Woo D, Ewing I, et al. Community socioeconomic status and prehospital times in acute stroke and transient ischemic attack: Do poorer patients have longer delays from 911 call to the emergency department? Stroke. 2006;37:1508–1513. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000222933.94460.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller ET, King KA, Miller R, Kleindorfer D. FAST stroke prevention educational program for middle school students: Pilot study results. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39:236–242. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200708000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwamm LH, Audebert HJ, Amarenco P, Chumbler NR, Frankel MR, George MG, et al. Recommendations for the implementation of telemedicine within stroke systems of care: A policy statement from the american heart association. Stroke. 2009;40:2635–2660. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Dávalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Zoppo GJ, Saver JL, Jauch EC, Adams HP. Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: A science advisory from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2009;40:2945–2948. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudd AG, Hoffman A, Grant R, Campbell JT, Lowe D. Stroke thrombolysis in england, wales and northern ireland: How much do we do and how much do we need? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2011;82:14–19. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.203174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majersik JJ, Smith MA, Zahuranec DB, Sánchez BN, Morgenstern LB. Population-based analysis of the impact of expanding the time window for acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 2007;38:3213–3217. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broderick J, Brott T, Kothari R, Miller R, Khoury J, Pancioli A, et al. The greater Cincinnati/Northern kentucky stroke study: Preliminary first-ever and total incidence rates of stroke among blacks. Stroke. 1998;29:415–421. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whisnant JP, Basford JR, Bernstein EF. Special report from the national institute of neurological disorders and stroke: Classification of cerebrovascular diseases III. Stroke. 1990;21:23–28. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams HP, Jr, Del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: A guideline from the american heart association/American stroke association stroke council, clinical cardiology council, cardiovascular radiology and intervention council, and the atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease and quality of care outcomes in research interdisciplinary working groups. Stroke. 2007;38:1655–1711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams HP, Jr, Del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: A guideline from the american heart association/American stroke association stroke council, clinical cardiology council, cardiovascular radiology and intervention council, and the atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease and quality of care outcomes in research interdisciplinary working groups. Stroke. 2007;38:1655–1711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, Brott TG, Toni D, Grotta JC, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: An updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. The Lancet. 2010;375:1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung TW, Wong KS. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: Safe and effective outside the 3-hour time window? Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009;5:70–71. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lansberg MG, Schrooten M, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN, Saver JL. Treatment time-specific number needed to treat estimates for tissue plasminogen activator therapy in acute stroke based on shifts over the entire range of the modified rankin scale. Stroke. 2009;40:2079–2084. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marler JR. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. NEW ENGL J MED. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, Reeves MJ, Bhatt DL, Grau-Sepulveda MV, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: Patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123:750–758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.974675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Dávalos A, Hacke W, Millán M, Muir K, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3–4.5 h after acute ischaemic stroke (SITS-ISTR): An observational study. Lancet. 2008;372:1303–1309. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cocho D, Belvís R, Martí-Fàbregas J, Molina-Porcel L, Díaz-Manera J, Aleu A, et al. Reasons for exclusion from thrombolytic therapy following acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2005;64:719–720. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152041.20486.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masrur S, Abdullah AR, Smith EE, Hidalgo R, El-Ghandour A, Rordorf G, et al. Risk of thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke in patients with current malignancy. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2011;20:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]