Abstract

Particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) is a multisubunit metalloenzyme complex used by methanotrophic bacteria to oxidize methane in the first step of carbon assimilation and energy production. In this chapter, we detail methods to prepare metal free (apo) membrane-bound pMMO and to reconstitute apo pMMO with metal ions. We also describe protocols to clone, express, and refold metal-loaded soluble domain constructs of the pmoB subunit. These approaches were used to address fundamental questions concerning the metal content and location of the pMMO active site.

1. Introduction

Particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) is a metalloenzyme that catalyzes the conversion of methane to methanol in methanotrophic bacteria (Hakemian and Rosenzweig, 2007). Understanding how pMMO oxidizes methane, the most inert hydrocarbon (C–H bond strength 104 kcal mol−1), could lead to new catalytic processes (Himes and Karlin, 2009). In addition, pMMO has potential applications in bioremediation and greenhouse gas removal (Semrau et al., 2010). However, studies of pMMO have been plagued by controversy surrounding the metal composition and location of the active site (Rosenzweig, 2008).

It is widely accepted that there is a functional role for copper in pMMO since all active preparations contain some amount of copper and copper is linked to expression of the enzyme (Hakemian and Rosenzweig, 2007; Lieberman and Rosenzweig, 2004; Semrau et al., 2010). Some preparations of pMMO also contain iron, and it has been proposed that the active site is a dinuclear iron center (Martinho et al., 2007). However, some active preparations of pMMO have been reported to contain no detectable iron (Chan and Yu, 2008; Yu et al., 2003). To determine how many of which metal ions are required for pMMO activity, we developed a method to remove the metal ions from membrane-bound pMMO (Balasubramanian et al., 2010). All enzymatic activity is abolished by metal extraction, although SDS-PAGE analysis indicates that the three subunits, pmoB, pmoA, and pmoC, remain intact. Activity of pMMO, measured by propylene epoxidation or methane oxidation, can then be restored by titrating in 2–3 equivalents of copper per 100 kDa pMMO protomer (composed of one copy each of the three subunits). Addition of iron has no effect on activity (Balasubramanian et al., 2010). These data indicate that copper is the active site metal in pMMO and provide a means to study pMMO without the variable metal content observed with individual isolations.

The crystal structures of pMMO from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) (Lieberman and Rosenzweig, 2005) and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (Hakemian et al., 2008) both contain dicopper centers in the soluble, periplasmic domains of the pmoB subunit. The histidine ligands to this dicopper site are highly conserved. This observation, combined with the stoichiometry of the copper-dependent activity data (Balasubramanian et al., 2010), is consistent with the possibility that the dicopper center is the active site. To test this hypothesis, we developed a recombinant system to express and characterize the soluble domains of pmoB (denoted spmoB) (Balasubramanian et al., 2010). This system provides for the first time the opportunity to address fundamental questions about pMMO by site-directed mutagenesis. Using biochemical assays and spectroscopic techniques, we showed that spmoB assembles metal cofactors similar to those present in wild type, intact pMMO and, most importantly, that spmoB can oxidize propylene and methane. We then pinpointed the dicopper center as the active site of pMMO via analysis of site-directed spmoB variants (Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

With these tools in hand, detailed mechanistic studies of pMMO are now possible. Here we detail the methods for generating metal free pMMO (apo pMMO) and reconstituting pMMO with metal ions. We also describe the design and expression of constructs of the pmoB subunit lacking the transmembrane regions (spmoB) and protocols to refold, metal load, and test activity of these spmoB proteins.

2. Preparation of apo pMMO Membranes and Metal Reconstitution

2.1. M. capsulatus (Bath) growth conditions

M. capsulatus (Bath) cells are fermented using a New Brunswick Scientific BioFlo 4500 Benchtop Fermentor/Bioreactor. 12 l of nitrate mineral salts (NMS) media (2 g/l KNO3, 1 g/l MgSO4·7H2O, 0.1 g/l CaCl2·2H2O) are combined with 6 ml of 20× trace elements solution (500 mg/l Na2EDTA, 200 mg/l FeSO4·7H2O, 10 mg/l ZnSO4·7H2O, 3 mg/l MnCl2·4H2O, 30 mg/l H3BO3, 20 mg/l CoCl2·6H2O, 1 mg/l CuCl2·2H2O, 3 mg/l Na2MoO4·2H2O), 6 ml of 20× sodium molybdate (500 mg/l Na2MoO4·2H2O), 120ml of 10× phosphate buffer (pH 6.8; 53.4 g/lNa2HPO4·7H2O, 26 g/l KH2PO4), 6 ml of 0.1 M CuSO4·5H2O, and 9.6 ml of 0.1 M FeEDTA (ethylenediamine–tetraacetic acid ferric–sodium salt). The final Cu and Fe concentrations are 50 and 80 µM, respectively. Methane is bubbled through the media for 30 min prior to inoculation with 5–10 g of cell paste resuspended in sterile NMS. The fermentation is then maintained at 45 °C with a 4:1 air:methane ratio and constant agitation of 300 rpm. Cells are harvested at an OD600 of 5–7, centrifuged at 8000×g, washed in 25 mM Pipes, pH 6.8, recentrifuged, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

2.2. pMMO membrane isolation

Frozen M. capsulatus (Bath) cells are resuspended and lysed either by sonication or microfluidization. Intracytoplasmic membranes are isolated by low speed centrifugation to remove cell debris, followed by several rounds of ultracentrifugation and homogenization to remove contaminating soluble proteins.

-

Frozen cells are thawed in 200–300 ml of freshly prepared lysis buffer (25 mM PIPES, pH 6.8–7.0, 250 mMNaCl) and transferred to a stainless steel beaker on ice.

For sonication, the instrument is tuned and a stir bar is added to the resuspended cells. Cells are sonicated, with stirring, on ice at 4 °C for 10 min with 1 s on/off pulses at 40% max power

For microfluidization, the heat-exchanging coil is submerged in an ice water bath and the instrument is flushed with ice cold lysis buffer. The cells are then passed through the microfluidizer three times at a constant pressure of 180 psi.

The lysate is centrifuged at 20,000×g for 1.5 h to remove cell debris.

The supernatant is ultracentrifuged at 160,000×g for 1 h and the pelleted membranes resuspended in fresh lysis buffer and homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer. This process is repeated three times to ensure complete removal of contaminating soluble proteins.

The protein concentration of the resulting pMMO-containing membranes is determined using the detergent-compatible Bio-Rad DC protein assay. The membranes are then diluted to 10–20 mg/ml, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in a −80 °C freezer.

2.3. pMMO activity assays

pMMO activity is typically measured using a propylene epoxidation assay or a methane oxidation assay with duroquinol as the reductant. In general, freshly prepared duroquinol is combined with pMMO in a septum sealed vial. The assay is initiated by replacing a volume of the headspace gas with either propylene or methane and incubating. The propylene oxide or methanol produced is quantitated by gas chromatography and compared with known standards.

1. Frozen pMMO membranes are thawed on ice. Duroquinol is freshly prepared by following the method of Zahn and DiSpirito (1996), which involves reducing duroquinone with sodium dithionite and sodium borohydride in acidic ethanol.

A small spatulaful of duroquinol (0.9–1.1 M final concentration, in excess for the purpose of the assay) is combined with 50–250 ml of pMMO membranes in a 1.5–3 ml septum sealed vial.

1–2 ml of the headspace gas is replaced with propylene or methane, and the vial is placed in a shaking water bath set at 45 °C and 200 rpm for 3 min.

-

The amount of propylene oxide or methanol produced is measured using a Hewlett Packard 5890A gas chromatograph.

Propylene oxide is detected by injecting 50–250 µl of the headspace gas onto a Porapak Q packed column (Supelco) maintained at a constant temperature of 180 °C and quantitated by comparison to a standard curve generated from ≥99% pure propylene oxide (Sigma Aldrich).

For methanol, the vial is heated to 85 °C for 10 min to stop the reaction and then cooled on ice. The assay mixture is then centrifuged for 2 min, and 3 µl of the clear solution is loaded onto an Rt-Q-BOND capillary column (Restek) maintained at a constant temperature of 75 °C. As above, methanol production is quantitated by comparison to a standard curve generated using > 99% pure methanol (Sigma Aldrich).

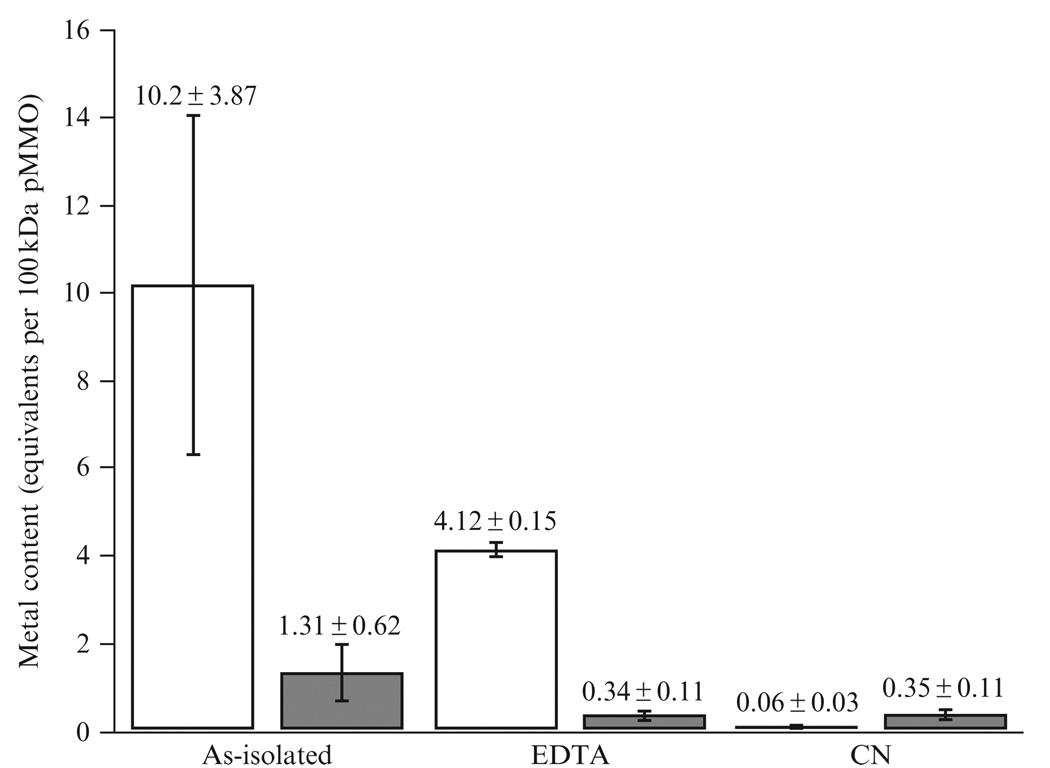

M. capsulatus (Bath) cells grown with 50 µM CuSO4 and 80 µM FeEDTA in the media typically produce pMMO that contains between 6–20 Cu and 0.5–2 Fe per 100 kDa pMMO protomer, with average values of 10.2 Cu and 1.31 Fe, as measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) (Fig. 13.1). Using the procedures detailed above, these isolated pMMO membranes exhibit specific activities of 50–200 nmol propylene oxide·min−1·mg pMMO−1 (Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

Figure 13.1.

Metal content of isolated pMMO membranes (seven independent isolations), EDTA treated membranes (three independent isolations) and CN− treated membranes (four independent isolations) expressed per 100 kDa pMMO protomer. The copper content is shown in white and the iron content in gray.

2.4. Metal removal with EDTA

Several groups have used EDTA to remove metal from isolated pMMO membranes (Basu et al., 2003; Takeguchi et al., 1998). Using an EDTA-containing buffer in a dialysis experiment, we were able to generate inactivated pMMO-containing membranes, but total metal removal was not achieved. ICP-OES analysis before and after EDTA treatment indicates that only ~6 Cu and ~1 Fe per 100 kDa pMMO protomer are removed using this method (Fig. 13.1).

Membrane-bound pMMO samples are digested in 5% trace-metal grade (TMG) nitric acid. The metal content (Cu, Fe, and Zn) is determined using ICP-OES by comparison with standard curves generated from atomic absorption standards diluted in 5% TMG nitric acid.

Three to 12 ml of pMMO membranes are placed in a 3500 MWCO Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassette (Thermo Scientific).

The cassette is initially dialyzed against 2 l of an EDTA chelating buffer (25 mM PIPES, pH 7, 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM Na2EDTA) with stirring at 4°C for 3 h before exchanging into fresh EDTA chelating buffer and dialyzing overnight.

After this overnight dialysis, EDTA is removed by dialyzing against 2 l of lysis buffer (25 mM PIPES, pH 6.8–7.0, 250 mM NaCl), exchanging every 2 h for a total of 12 l.

The metal content of these EDTA treated pMMO membranes is again measured by ICP-OES.

EDTA treated pMMO membranes contain ~4 Cu and ~0.3 Fe per 100 kDa (Fig. 13.1). In order to achieve total metal removal, a second procedure involving cyanide was developed.

2.5. Metal removal with cyanide

Prior to CN− treatment, the metal content of active pMMO-containing membranes is measured via ICP-OES. The amount of CN− used in the extraction buffer is based on the total copper concentration of the isolated membranes. To limit CN− exposure, the extraction buffer is maintained at a pH ≥ 8 and all open manipulations that involve CN− are performed inside a hood with the highest level of personal protective equipment (fluid-resistant lab coat, nitrile gloves, goggles). The institutional office of research safety must be consulted about proper working and disposal procedures. A 10-fold molar excess of CN− and ascorbic acid, relative to the total copper concentration, is added to the buffer. The highly buffered solution does not change pH upon addition of ascorbate.

A membrane-bound pMMO sample (6–12 ml) of predetermined copper concentration (measured by ICP-OES) is ultracentrifuged at 160,000×g for 1 h, resuspended, and homogenized in 25–50 ml of extraction buffer (50 mM MOPS, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl).

Solid KCN and l-ascorbic acid are added at 10-fold molar excess and the solution is covered with parafilm and stirred at room temperature for 30–60 min.

The CN− treated membranes are then ultracentrifuged 160,000×g for 1 h with the CN− buffer appropriately disposed of per institutional procedures, followed by resuspension and homogenization in 25–50 ml extraction buffer (containing no KCN or ascorbic acid).

The pMMO membranes are ultracentrifuged, resuspended, and homogenized an additional three times, resuspending in lysis buffer to remove all traces of CN−.

The metal content of these CN− extracted pMMO membranes is then determined by ICP-OES.

Following the metal extraction procedure detailed above, the resulting pMMO membranes contain, on average, ~0.06 Cu and ~0.35 Fe per 100 kDa pMMO (Balasubramanian et al., 2010). These values correspond to a total metal removal of ~99% of the Cu and ~73% of the Fe. Previously, we reported that purified pMMO contains a heme contaminant on the basis of an optical feature at 410 nm, X-ray absorption spectroscopic (XAS), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) data (Lieberman et al., 2003, 2006). Interestingly, an optical spectrum of solubilized CN− treated pMMO also exhibits an absorption peak at 410 nm. Thus, some portion of the iron (~0.05 Fe per 100 kDa pMMO or 14% of the total iron) that remains after the extraction procedure is from a contaminating iron-porphyrin.

2.6. Metal reconstitution

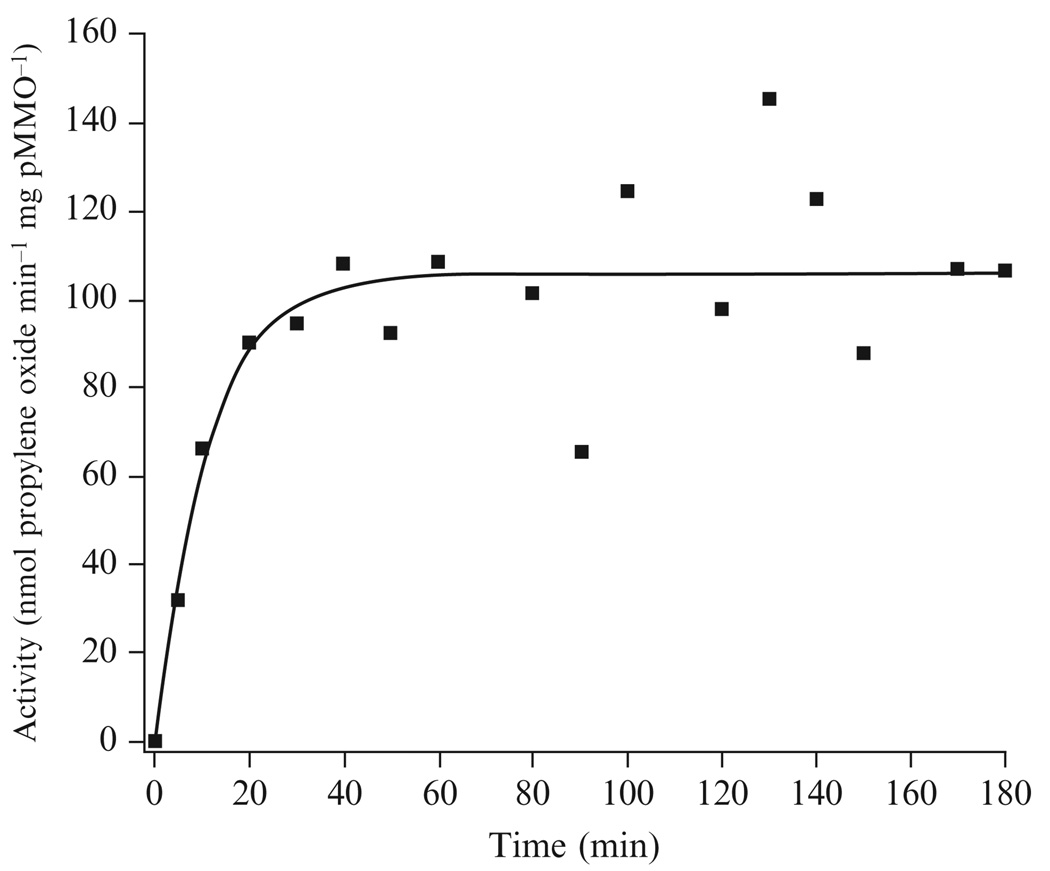

Metals (Cu and/or Fe) are reconstituted into pMMO stoichiometrically on a mole-to-mole basis assuming a molecular mass of 100 kDa. The exact concentration of the metal stock solutions are determined using ICP-OES. To control for dilution errors, the concentration of the metal stock solution is made such that the volume increase from metal additions is negligible relative to the total volume of the assay (volume of apo pMMO membranes used in the activity assay ≫ volume of metal stock solution added to the activity assay). After individual metal equivalents are added, the solution is mixed thoroughly and incubated for at least 30 min. The 30 min incubation time was chosen on the basis of time course experiments indicating that maximal activity is achieved after ~30 min incubation with added metals (Fig. 13.2). Following this 30 min incubation, activity is measured as described above.

Determine pMMO concentration using the detergent-compatible Bio-Rad DC protein assay.

Verify metal stock solution (CuSO4·5H2O, Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O) concentration by ICP-OES.

Add appropriate molar equivalents of CuSO4·5H2O or Fe (NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O to apo pMMO membranes, mix by pipetting or with a stir bar and incubate for at least 30 min. For consistency, all incubation times should be kept constant.

Add duroquinol, mix, and measure activity as detailed above (Section 2.3).

Figure 13.2.

Reconstituted pMMO activity as a function of time incubated with added metal equivalents. A representative time course with 2 equivalents of added Cu is shown. Maximum activity is achieved after approximately 30 min incubation.

Using this approach, we were able to recover ~70% of our original propylene epoxidation activity and ~90% of our methane oxidation activity by the addition of 2–3 equivalents of copper. The addition of iron has no effect on activity (Balasubramanian et al., 2010). Copper additions beyond 3 molar equivalents produced an inhibitory effect. The nature of this inhibition is not well understood, but appears to derive from a hydrogen peroxide-producing side reaction between duroquinol and aqueous copper (Miyaji et al., 2009). This activity loss is reversible, however, and can be remedied with the addition of commercial catalase (Sigma Aldrich) (Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

3. Soluble Domain Constructs of the pmoB Subunit

3.1. Design of vectors

Full-length M. capsulatus (Bath) pMMO contains three metal centers: a dicopper center and a mononuclear copper center, both coordinated by residues from the pmoB subunit, and a zinc center located within the membrane (Lieberman and Rosenzweig, 2005). The zinc derives from the crystallization buffer, and the nature of this site in vivo is not clear. Attempts to express full-length pMMO subunits in E. coli have not been successful. Based on the crystal structure and the aforementioned copper-dependent activity data, we designed, cloned, and expressed three constructs that span the soluble domain of pmoB (denoted spmoBd1, spmoBd2, and spmoB) as potential truncated versions of pmoB that might contain the active site. The pET21b(+) (Novagen) vector was chosen for the expression of the three domains. The following rationale and methods were used in the design of the expression constructs.

spmoBd1: the N-terminal domain of pmoB spanning residues 33–172. This domain contains all the ligands to the two copper centers. The dicopper center is coordinated by His 33, His 137, and His 139, and the monocopper center is coordinated by His 48 and His 72. A forward primer containing an NdeI site 5′-ggaattccatatgcacggtgagaaatcgcagg-3′ and a reverse primer containing an HindIII site 5′-gtgatccaagctttccggtggtgacggggttgcgaa-3′ are used for PCR amplification from M. capsulatus (Bath) genomic DNA. Both the PCR products and the vector are digested using NdeI/HindIII enzymes and ligated.

spmoBd2: the C-terminal domain of pmoB spanning residues 265–414. This domain does not bind any metal ions in the crystal structure. The forward primer 5′-gagaagcaagcttggaggaggacaggccgccggcaccatgcgtgg-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-gagatcccaagcttacatgaacgacgggatcagcgg-3′ are used for PCR amplification of the region from M. capsulatus (Bath) genomic DNA. As for generation of the spmoBd1 construct, NdeI/HindIII enzymes are used to digest both the PCR products and the vector, which are subsequently ligated.

spmoB: a third expression construct that connects the N-terminal (spmoBd1) and the C-terminal (spmoBd2) domains of pmoB via a GKLGGG linker instead of the two transmembrane helices present in native pMMO. For the generation of spmoB, we used spmoBd2 amplified with primers 5′-gagaagcaagcttggaggaggacaggccgccggcaccatgcgtgg-3′ and 5′-gagatcccaagcttacatgaacgacgggatcagcgg-3′. Both of these primers contain HindIII restriction sites. HindIII digested spmoBd2 is ligated to NdeI/HindIII digested spmoBd1 DNA. The ligated DNA containing spmoBd1 and spmoBd2 results in the spmoB insert with NdeI and HindIII at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The NdeI-spmoBd1-spmoBd2-HindIII is then ligated to the NdeI/HindIII digested pET21b(+) vector.

The coding regions of spmoBd1, spmoBd2, and spmoB were verified using DNA sequencing. A silent mutation was identified at position 1076, but did not change the amino acid.

3.2. Expression of the soluble domains of pmoB

The expression of inserts in the pET21b(+) vector is controlled by a T7 promoter. For protein expression, plasmid containing the appropriate insert is transformed into BL21(DE3) or Rosetta (DE3) pLysS strains of E. coli. The expression strains are plated on LB containing 50 µg/ml ampicillin. Colonies of E. coli appear on the plates after an overnight growth at 37 °C.

An overnight culture is grown using three colonies from the plate.

Cells from an overnight culture are used as a starter culture for growth in 1 l of LB supplemented with 50 µg/ml ampicillin.

After 3 h of growth at 37 °C, when the optical density of the cells reaches an OD600 of 0.6, 0.5 mM IPTG is added and the cells are grown for an additional 4–6 h post induction.

The cells are harvested by centrifugation at 5000×g for 10 min.

The cell pellets are resuspended in a total of 100–200 ml of lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris–Cl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, aliquoted into 50 ml falcon tubes, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in a −20 °C freezer until further processing.

3.3. Isolation and purification of inclusion bodies

Both spmoBd1 and spmoB always express as inclusion bodies. Growth experiments performed at 18 °C with an incubation time of 1 h produced partially soluble spmoBd2. However, for consistency, all growths are performed at 37 °C with an incubation time of at least 4 h. The spmoBd1, spmoBd2, and spmoB proteins are then purified from inclusion bodies.

Frozen cells expressing spmoBd1, spmoBd2, or spmoB are thawed in warm water. Cells are lysed by sonication for 10 min with a 10 s on and 30 s off pulse sequence on ice. The output power is set at 50%.

The cell lysate is centrifuged at 3000×g for 30 min. This step separates inclusion bodies from the cell debris. The supernatant is discarded and does not contain any overexpressed protein.

The usually white inclusion body pellet is resuspended with 50–100 ml of a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–Cl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100. A Dounce homogenizer is used to completely homogenize the solution.

The mixture is centrifuged at 10,000×g for 15 min and the supernatant discarded. This wash procedure is repeated three times. The use of Triton X-100 containing wash buffers eliminates most of the contaminating proteins and produces inclusion bodies that are almost homogeneous.

As a final step, the inclusion bodies are washed using the same buffer, but without detergent. The yield of pure inclusion bodies from each liter of cell culture is 1–3 g.

For solubilization of inclusion bodies in urea, 20 ml of freshly prepared 8 M urea is added per gram of purified inclusion bodies. This ratio of urea to inclusion bodies results in almost complete solubilization. The mixture is completely resuspended using a Dounce homogenizer and left to stir at room temperature for at least 1 h. After approximately 1 h, the mixture turns transparent, indicating solubilization. Since the soluble domains do not contain any cysteines, no reducing agent was added.

Urea solubilized inclusion bodies are then centrifuged at 15,000×g for 30 min to remove any insoluble material.

The supernatant from the urea solubilized inclusion bodies is aliquoted and stored at −80 °C for long-term use or kept at 4 °C for immediate refolding.

3.4. Refolding of inclusion bodies

Urea solubilized inclusion bodies are refolded using a stepwise dialysis procedure against buffers with decreasing urea concentrations. All urea stocks are freshly prepared and are not heated.

The protein, at a concentration of ~5 mg/ml in 8 M urea, is dialyzed against 7 M urea buffered with 50 mM Tris–Cl, pH 8.0, for 3 h. This process is repeated with decreasing urea concentrations (6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0.5 M) for at least 3 h in each buffer.

After dialysis against a buffer containing 0.5 M urea, the final dialysis is performed against 20–50 mM Tris–Cl, pH 8.0, or 20 mM PIPES, pH 7.0, containing 250 mM NaCl and no urea. The efficiency of refolding is estimated to be approximately 0.2% of the total protein. This estimate is based on comparing SDS-PAGE band intensities of the initial and final material.

After the final dialysis step, precipitates are removed by centrifugation at 20,000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. On occasion, the precipitates are removed by pelleting using an ultracentrifuge at 40,000×g for 30 min.

Attempts at loading copper into refolded proteins resulted in complete protein precipitation. Therefore, a reconstitution procedure was developed in which copper is introduced into the protein in a stepwise fashion during the refolding process. Cu(II) (either CuSO4 or CuCl2) is added to the 6 M urea dialysis buffer to a final concentration of 1 mM. A stepwise dialysis procedure using urea buffers without copper, similar to that described in step 1, is used for subsequent refolding. A final dialysis step against a buffer lacking both urea and copper likely eliminates all unbound copper.

3.5. Copper assays

The copper content of the refolded proteins can be determined by ICP-OES or using a colorimetric bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method.

For analysis by ICP-OES, the total metal content (copper, zinc, and iron) is measured as described in Section 2.4.

-

In the second procedure, BCA is used. Two molecules of BCA exhibit strong absorption features at 360 and 562 nm upon coordination to Cu (I). The copper contents determined from the samples are compared to standard curves generated from dilutions of atomic absorption standards (Sigma).

Standards of 0–60 µM are prepared from copper atomic absorption standards (Sigma).

125 µl of 30% trichloroacetic acid is added to 325 µl of the sample or the standard. This step precipitates the protein and releases all of the bound copper.

To this mixture, 100 µl of a freshly prepared 1.7 mM ascorbate solution is added. Addition of ascorbate reduces all of the Cu(II) to Cu(I).

In the detection step, 400 µl of BCA solution (prepared by mixing 6 ml of 1% BCA, 3.6 g NaOH, 15.6 g Hepes acid, and 84 ml water) is added and the mixture incubated at room temperature for 5 min (Brenner and Harris, 1995).

The mixture is centrifuged at 14,000×g for 5 min to remove precipitates and the absorbance measured at 360 and 562 nm.

Molar ratios of protein bound copper are calculated by dividing the total copper concentrations by the protein concentrations determined using the theoretical extinction coefficients at 280 nm. Using this method, spmoBd1, spmoBd2, and spmoB bind 1.59 ± 0.84, 0.24 ± 0.09, and 2.84 ± 0.66 copper ions, respectively (Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

We used XAS to assess if the copper reconstituted into both CN− treated apo pMMO and the refolded soluble domain constructs forms a dicopper center. Best fits for the second shell scattering obtained from the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis of copper-reconstituted apo pMMO and spmoB suggest that a copper cluster similar to that in native pMMO is present (Balasubramanian et al., 2010; Hakemian et al., 2008; Lieberman et al., 2006).

3.6. Methods to assess refolding

Two methods can be used to assess the effectiveness of the refolding and copper reconstitution procedure, circular dichroism, and size exclusion chromatography.

Using protein concentrations of 1–2 µM in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, an average of 5 scans are collected at 1 nm resolution at 20 °C using a 2 mm path length quartz cuvette. The spectra are similar to those measured for laccase, which has a typical, well-characterized cupredoxin fold (Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

A Superdex G75 or Superdex S200 column is equilibrated with degassed buffer containing 20 mM Pipes, pH 7.0, and at least 150 mM NaCl. A volume of 0.1–0.5 ml of protein at a concentration of ~1 mg/ml is injected onto the column for analysis. Stokes radii of the samples are estimated by comparison of the elution profile to that of the standard proteins with known molecular mass. Under these conditions, the soluble domains of pmoB elute both in the void volume and at volumes that correspond to molecular masses of the protein monomers. There is no indication of trimerization (Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

3.7. Activity assays of the soluble pmoB domains

Activity assays are performed as described for pMMO (Section 2.3) with the following modifications.

-

Propylene epoxidation.

Excess duroquinol is added to 350 µl of sample and mixed thoroughly.

ml of headspace gas is removed and replaced with 2 ml of propylene and 0.5 ml of air.

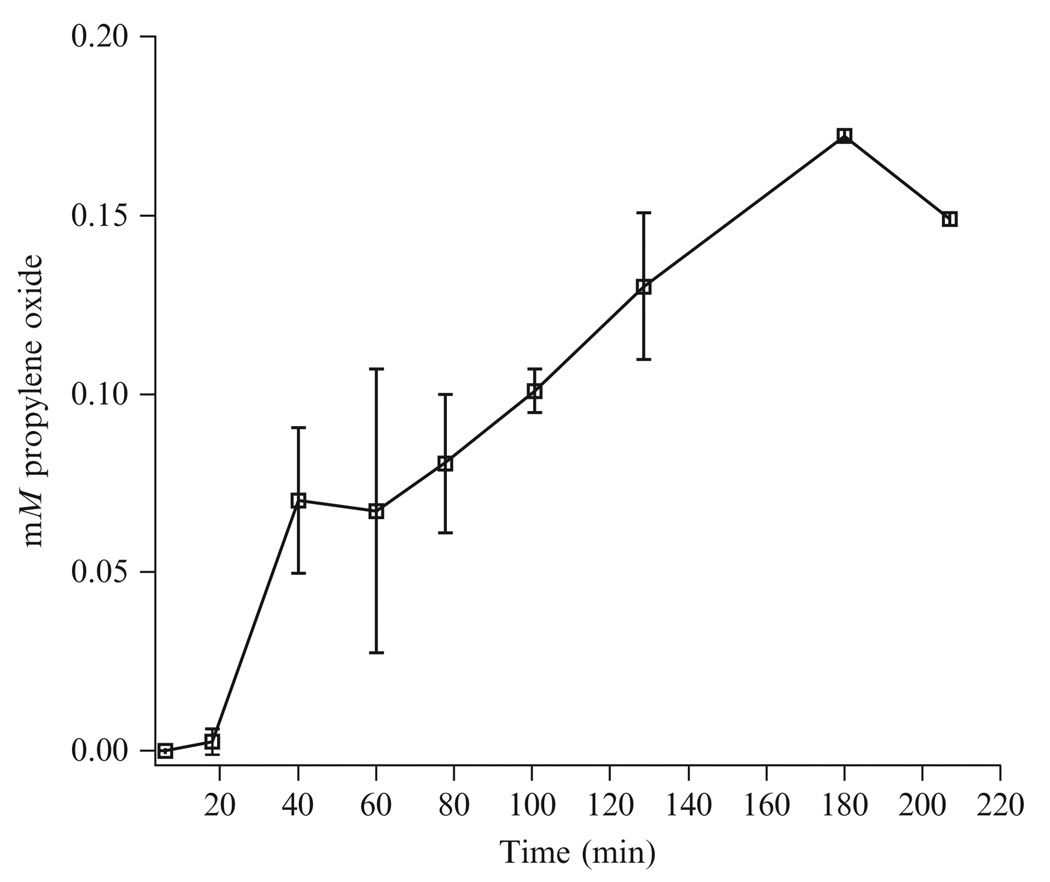

The mixture is incubated in a shaking water bath at 45 °C for at least 1 h prior to sampling the headspace gas for propylene oxide. Reliable detection of propylene oxide formed under these assay conditions for spmoB requires at least 40 min incubation time (Figure 13.3).

In the literature, propylene oxide formation is always represented in specific activity units of nmol propylene oxide·min−1·mg protein−1. For the soluble pmoB constructs, activity is represented as nmol propylene oxideµmin−1·mol protein−1 (Balasubramanian et al., 2010). Moles are used instead of mg to account for the differences in molecular masses between the spmoB proteins and native pMMO.

-

Methane oxidation.

2 ml of the headspace gas in the reaction vial is replaced with 2 ml of methane.

After a 1 hr incubation, the reaction vial is heated at 85 °C for 10 min to stop the reaction and cooled on ice.

The samples are then transferred to an eppendorf tube and centrifuged to remove any protein debris.

3 µl of the clear liquid is injected onto the capillary column that is held at a constant temperature of 75 °C.

Figure 13.3.

Time course of spmoB activity. The activity can be measured reliably after 40 min reaction incubation. For uniformity, all samples are measured after at least 1 h incubation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant GM070473. We thank Liliya Yatsunyk, Megen Culpepper, Swati Rawat, and Timothy Stemmler for assistance at various stages of this project.

REFERENCES

- Balasubramanian R, Smith SM, Rawat S, Stemmler TL, Rosenzweig AC. Oxidation of methane by a biological dicopper centre. Nature. 2010;465:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature08992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu P, Katterle B, Andersson KK, Dalton H. The membrane-associated form of methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) is a copper/iron protein. Biochem. J. 2003;369:417–427. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner AJ, Harris ED. A quantitative test for copper using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1995;226:80–84. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SI, Yu SSF. Controlled oxidation of hydrocarbons by the membrane-bound methane monooxygenase: The case for a tricopper cluster. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:969–979. doi: 10.1021/ar700277n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakemian AS, Rosenzweig AC. The biochemistry of methane oxidation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:223–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061505.175355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakemian AS, Kondapalli KC, Telser J, Hoffman BM, Stemmler TL, Rosenzweig AC. The metal centers of particulate methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6793–6801. doi: 10.1021/bi800598h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himes RA, Karlin KD. Copper-dioxygen complex mediated C-H bond oxygenation: Relevance for particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman RL, Rosenzweig AC. Biological methane oxidation: Regulation, biochemistry, and active site structure of particulate methane monooxygenase. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;39:147–164. doi: 10.1080/10409230490475507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman RL, Rosenzweig AC. Crystal structure of a membrane-bound metalloenzyme that catalyses the biological oxidation of methane. Nature. 2005;434:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature03311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman RL, Shrestha DB, Doan PE, Hoffman BM, Stemmler TL, Rosenzweig AC. Purified particulate methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) is a dimer with both mononuclear copper and a copper-containing cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3820–3825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536703100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman RL, Kondapalli KC, Shrestha DB, Hakemian AS, Smith SM, Telser J, Kuzelka J, Gupta R, Borovik AS, Lippard SJ, Hoffman BM, Rosenzweig AC, Stemmler TL. Characterization of the particulate methane monooxygenase metal centers in multiple redox states by X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:8372–8381. doi: 10.1021/ic060739v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinho M, Choi DW, DiSpirito AA, Antholine WE, Semrau JD, Münck E. Mössbauer studies of the membrane-associated methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus Bath: Evidence for a diiron center. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15783–15785. doi: 10.1021/ja077682b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaji A, Suzuki M, Baba T, Kamachi T, Okura I. Hydrogen peroxide as an effecter on the inactivation of particulate methane monooxygenase under aerobic conditions. J. Mol. Catal. B. 2009;57:211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig AC. The metal centres of particulate methane monooxygenase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:1134–1137. doi: 10.1042/BST0361134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semrau JD, Dispirito AA, Yoon S. Methanotrophs and copper. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010;34:496–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeguchi M, Miyakawa K, Okura I. Purification and properties of particulate methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. J. Mol. Catal. A. 1998;132:145–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1009278216452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SS-F, Chen KH-C, Tseng MY-H, Wang Y-S, Tseng C-F, Chen Y-J, Huang DS, Chan SI. Production of high-quality particulate methane monooxygenase in high yields from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) with a hollow-fiber membrane bioreactor. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:5915–5924. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.20.5915-5924.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn JA, DiSpirito AA. Membrane-associated methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:1018–1029. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1018-1029.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]