Abstract

Background:

Uncorrected refractive errors are the main cause of vision impairment in school-aged children. The current study focuses on the effectiveness of school eye screening in correcting refractive errors.

Objectives:

1. To study the magnitude of visual impairment among school children. 2. To assess the compliance of students for refraction testing, procurement and use of spectacles.

Materials and Methods:

An intervention study was conducted in schools of the north- west district of Delhi, in the rural field practice area of a medical college. Students studying in five government schools in the field practice area were chosen as the study subjects.

Results:

Out of 1123 students enrolled, 1075 (95.7%) students were screened for refractive errors. Low vision (visual acuity < 20/60) in the better eye was observed in 31 (2.9%) children and blindness (visual acuity <20/200) in 10 (0.9%) children. Compliance with referral for refraction was very low as only 51 (41.5%) out of 123 students could be tested for refraction. Out of 48 students, 34 (70.8%) procured spectacles from family resources but its regular use was found among only 10 (29.4%) students. The poor compliance among students stems out of various myths and perceptions regarding use of spectacles prevalent in the community.

Conclusion:

Refractive error is an important cause of avoidable blindness among rural school children. Behavior change communication among rural masses by spreading awareness about eye health and conducting operational research at school and community level to involve parent's teachers associations and senior students to motivate students for use of spectacles may improve utilization of existing eye health services in rural areas.

Keywords: Refractive error, rural area, school children, use of spectacles

Refractive errors are the leading cause of visual impairment in school-going and school-aged children reported in India and other developing countries.[1–8] Globally, a huge burden of uncorrected/unaided refractive errors has been reported in multiple surveys conducted among school-aged children in both Asiatic and other nations. (India: 2.63- 7.4%;[2–6]; Nepal:8.1%;[7]; Pakistan:8.9%;[8]; Malaysia:17.1%;[9]; Iran: 3.8%;[10]; South Africa:1.4%;[8]; Brazil: 4.82%;[11]; Australia: 10.4%;[12]; Chile: 15.8%[13]).

Early detection and correction of vision problem is found to have educational and behavioral benefits, and certainly enhances Quality of Life.[14] Screening for visual impairment and identification of the children suffering from refractive errors and encouraging them to take corrective measures in the form of spectacles can therefore play an important role in preventing long- term visual disability. There exists a paucity of studies among the rural school children of India that assesses the compliance of students for refraction testing and use of spectacles subsequent to visual screening.

It is reported that provision of free spectacles does not provide for long- term sustainability and is associated with a relatively low rate of subsequent spectacle compliance.[15] Therefore this study was planned to determine the magnitude of visual impairment among school children in a rural area of Delhi and to assess their compliance for refraction and spectacles procurement through family resources and its use.

Materials and Methods

The current study was conducted in five schools of the north- west district of Delhi, in the rural field practice area of the Department of Community Medicine of a medical college of New Delhi. New Delhi, the capital of India is divided into nine districts and the north-west district is the most populated district with 20.6% of the total state population. As per the Economic Survey of Delhi (2005-06)[16] the rural population constitutes 9.3% of the district population. This area is categorized as rural as the population density is less than 400 per sq km and more than 25% of the male working population is engaged in agricultural pursuits.[16]

All five middle and secondary government schools in and within two kilometers of the field practice area were included in the study. Consent for conducting the study was obtained from the Deputy Director (Education), North- West District and the principals of the chosen schools. Study subjects comprised all students in Class VII, VIII and IX of all the five schools. Students of these classes were able to understand and follow instructions while doing refraction testing and could be easily examined. They were also able to explain the proceedings to their parents for taking consent. A pre-designed, pre-tested questionnaire was used for collecting identification data and information on visual acuity and spectacle use. As no student was found to be using spectacles, uncorrected / unaided visual acuity of all the students was assessed by Snellen's chart by a single experienced optometrist to avoid inter-observer variation. Students who were absent on the day of check-up were followed for two more visits and in case of failure to meet them, they were categorized as non-response.

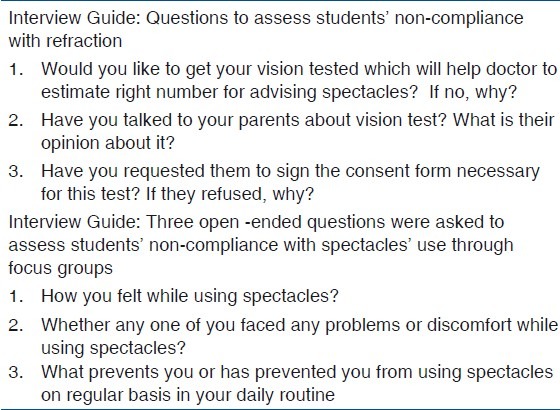

According to the definition used in the National Program of Control of Blindness in India,[17] visual acuity in the better eye < 20/60 was considered as low vision and <20/200 as blindness. A cut-off of < 20/30 in either eye was used to define abnormal vision.[18] Children with vision <20/30 in either eye were referred for refraction. These students were motivated to discuss the issue at home and get a written consent from their parents for refraction test. The students who did not submit the consent form were reminded at least two more times on separate occasions within a one-week period before the team visited the school for refraction test. The students who gave written consent were administered cycloplegic drugs (tropicamide 1%) and detailed eye examination of the anterior segment, media and fundus was done followed by refraction by an ophthalmologist. Those who did not undergo refraction were interviewed to assess reasons for non-compliance [Table 1]. A pre-designed, structured questionnaire was used to report the most probable reason due to which student had not submitted the consent form in-spite of repeated reminders.

Table 1.

Interview Guide: Questions to assess students’ non-compliance with refraction and spectacles’ use

Children whose visual acuity improved with correction of refractive error (best corrected visual acuity) in either eye were prescribed spectacles. The students were motivated to buy the spectacles from their own family resources. They were followed up about nine months later regarding purchase and use of spectacles. For those students who did not procure spectacles or were not using these regularly, focus group discussions were conducted by single investigator to assess the reasons for non-compliance. Written notes were made during the discussions which were later word processed. Thematic analysis of these interview notes was done based on discussion between all the authors. In each group discussion five to eight students participated. Before starting the study approval was taken from institutional ethical committee.

Data Analysis: Data was entered in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and any inconsistencies were looked for. SPSS Version 11.01 was used for entry and to calculate frequencies of quantitative data. Thematic analysis was done for qualitative data to identify the major reasons for non- compliance for refraction or spectacles procurement or non-use.

Results

A total of 1123 students were enrolled for the study. Forty-eight students could not be contacted for screening despite repeated efforts. Thus 1075 (95.7%) students were screened from five schools and non-response rate was 4.3%. The mean age of students was 14.25 years with a range of 11 to 18 years. There were 502 (46.8%) male and 573 (53.2%) female students.

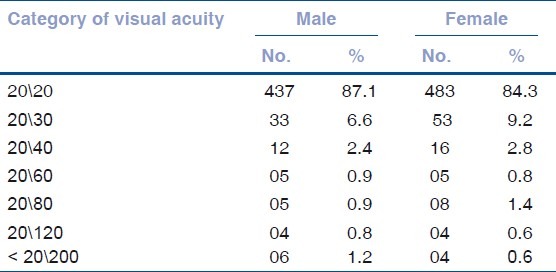

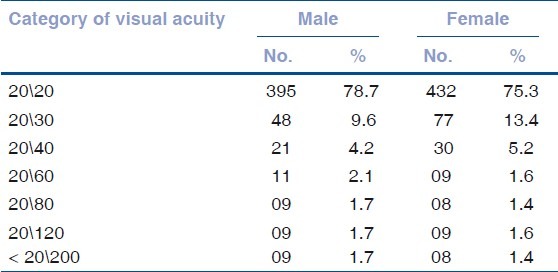

Low vision (< 20/60) in the better eye was found in 2.9% children; while 0.9% children had visual acuity equivalent to blindness (<20/200) [Tables 2 and 3]. None of the students with visual impairment were using spectacles.

Table 2.

Sex-wise distribution of uncorrected visual acuity among the students in better eye (M= 502, F= 573)

Table 3.

Sex-wise distribution of uncorrected visual acuity among the students in worse eye (M= 502, F= 573)

Fifty-nine (11.7%) boys and 64 (11.2%) girls with visual acuity of less than 20/30 in either eye were asked to obtain consent from parents for refraction. Out of these, only 22 (37.3%) boys and 29 girls (45.3%) obtained written consent from parents and complied for refraction while the rest of the students (62.7% boys and 54.7% girls) were considered to be non-compliant.

For the students who complied for refraction, spectacles were prescribed. The students were motivated to buy them through their own family sources. One boy with probable diagnosis of retinal pathology was referred to a tertiary care center.

All the students who were prescribed spectacles were followed up eight-nine months later. One boy and one girl student were excluded from the analysis as they had dropped out from the school, resulting in 4% loss to follow-up. Twelve out of 20 (60.0%) boys and 22 out of 28 girls (78.6%) procured the spectacles. Regular use of spectacles, determined based on voluntary spectacles’ usage for daily chores along with studies was found to be present in only 10 students (five boys and five girls) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Compliance among students for refraction and procuring spectacles (boys =57; girls = 63)*

No significant association was present between the gender of students and compliance with refraction (P>0.05) and regular use of spectacles (P>0.05).

Reasons for non-compliance with refraction

Out of 72 students who had impaired vision and had not undergone refraction, 10 (13.9%) students were absent on the day of refraction, 22 (30.6%) were not willing to undergo refraction, 18 (25.0%) stated having forgot to get the consent form signed, 17 (23.6%) indicated parental refusal {no need (8); spectacles further deteriorate sight (6); cited no reason (3)} and 5 (6.9%) stated to have lost consent forms.

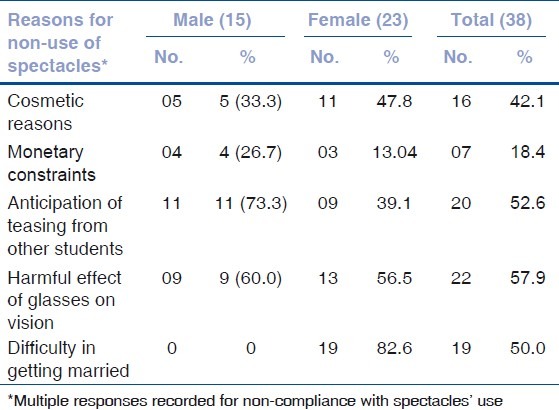

Reasons for non-procurement / non-use of spectacles

In focus group discussions the main reasons reported for non-purchase/ irregular use of spectacles were: cosmetic reasons, monetary constraints, anticipation of teasing from other students and widespread false believes about the harmful effect of glasses on vision. Difficulty in getting married was one of the major reasons reported by girls for their reluctance in using spectacles [Table 5].

Table 5.

Reasons for non-use of spectacles among students (boys =15; girls = 23)*

Discussion

Uncorrected refractive error is reported as the main cause of visual impairment in school children in India and in other parts of the world.[1–13] In the present study, vision equivalent to blindness (< 20\200) was found in 0.93% children which was higher compared to similar studies conducted among rural and urban school-aged children from other parts of India.[2–6,19] The present study reported an equivalent proportion of children with visual acuity of 20/40 or worse (6.4%) in the better eye which is comparable to other India-based studies (2.63-7.4%).[2–6] Danadona et al.,[19] observed that 0.18% of rural school-aged children are blind and another 2.4% are visually impaired but these proportions can be reduced to 0.13% and 0.65%, respectively, with the use of refractive correction. The higher magnitude of students with blindness and low vision in the current study may be attributed to the fact that study subjects were of rural background and higher age group. Poor access and utilization of eye health services among rural school children, worsening of uncorrected existing myopia and overt manifestation of latent myopia in the older age group might be the reason for a relatively higher magnitude of visual impairment.

The estimates of refractive error in the present study may still be under- reported because a large proportion of children with visual impairment did not comply with the refraction test. Low compliance with refraction and spectacles’ use was also observed in a study conducted in rural China where only one-third of the students advised to use spectacles obtained them and only a quarter of those wore the glasses regularly.[20] These findings are essential for visual health program planners as studies reveal that barriers other than economic constraints are present which prevent adoption of desired behaviors and utilization of accessible eye services.[20,21]

Gender of the student was not found to have any significant bearing on compliance with refraction testing and spectacles’ use. This was different from the observations made in rural students from other parts of the world where girls owning spectacles were significantly more likely to wear them as compared to boys.[21]

Non-compliance with refraction testing (boys- 64.9% and girls- 55.6%) and non-procurement of spectacles and their irregular use in the current study reflects lack of awareness about visual health among rural school students and various false beliefs and perceptions regarding use of spectacles, prevalent in rural communities. Behavior change communication strategies targeting school children in rural areas and school authorities’, especially involving teachers and parents at the time of visual screening of children are needed to overcome barriers related to refractive error correction.

Conclusion

Low compliance with refraction and subsequent low use of spectacles calls for operational research to explore different strategies among students like involvement of parent-teacher associations, active participation of senior students as guides and utilization of local media to spread awareness about eye health. Health-care workers and medical officers need to sensitize the rural community about problems of vision impairment. This can be done during meetings of the village health and sanitation committee (VHSC) and other local gatherings for behavior change of people regarding use of spectacles.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the valuable support received from school authorities and participant students in conducting this research activity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Naidoo KS, Raghunandan A, Mashige KP, Govender P, Holden BA, Pokharel GP, et al. Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3764–70. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalikivayi V, Naduvilath TJ, Bansal AK, Dandona L. Visual impairment in school children in Southern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1997;45:129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Ellwein LB, Munoz SR, Pokharel GP, Sanga L, et al. Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:623–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M, Sahare P, Narsaiah S, Munoz SR, et al. Refractive error in children in a rural population in India. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:615–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padhye AS, Khandekar R, Dharmadhikari S, Dole K, Gogate P, Deshpande M. Prevalence of uncorrected refractive error and other eye problems among urban and rural school children. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16:69–74. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.53864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaturvedi S, Aggarwal OP. Pattern and distribution of ocular morbidity in primary school children of rural Delhi. Asia Pac J Public Health. 1999;11:30–3. doi: 10.1177/101053959901100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nepal BP, Koirala S, Adhikari S, Sharma AK. Ocular morbidity in school children in Kathmandu. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:531–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.5.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alam H, Siddiqui MI, Jafri SI, Khan AS, Ahmed SI, Jafar M. Prevalence of refractive error in school children of Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:322–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:678–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:287–92. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salomão SR, Cinoto RW, Berezovsky A, Mendieta L, Nakanami CR, Lipener C, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in low-middle income school children in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4308–13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robaei D, Kifley A, Rose KA, Mitchell P. Refractive error and patterns of spectacle use in 12-year-old Australian children. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1567–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein LB. Refractive error study in Children: Results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:445–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pizzarello L, Tilp M, Tiezzi L, Vaughan R, McCarthy J. A school-based program to provide eyeglasses: Child sight. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1998;2:372–4. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holguin AM, Congdon N, Patel N, Ratcliffe A, Esteso P, Flores ST, et al. Factors associated with spectacle wear compliance in school aged Mexican children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:925–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Economic Survey of Delhi. 2005-06. [Last cited in 2011]. Available from: http://www.finmin.nic.in/reports/index.html .

- 17.Murthy GV, Bachani D, Gupta SK. Ophthalmology Section, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India. New Delhi: 2002. The Principles and Practice of Community Ophthalmology. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murthy GV. Vision testing for refractive errors in schools ‘Screening’ programmes in schools. Community Eye Health. 2000;13:3–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dandona L, Dandona R, Srinivas M, Giridhar M, Vilas K, Prasad MN, et al. Blindness in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:908–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Song Y, Liu X, Lu B, Choi K, Lam DS, et al. Spectacle acceptance among secondary school students in rural China: The Xichang Pediatric Refractive error study (X-Pres)- Report 5. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2895–902. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Congdon N, Zheng M, Sharma A, Choi K, Song Y, Zhang M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of spectacle non wear among rural Chinese secondary school children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1717–23. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]