Abstract

We report a rare case of Bietti's crystalline dystrophy presenting with choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) which was treated with three injections of intravitreal ranibizumab. The CNVM underwent scarring after the injections with stabilization of visual acuity at a follow-up period of 12 months suggesting that intravitreal ranibizumab may have a role in the management of CNVM in these rare cases.

Keywords: Bietti's crystalline dystrophy, choroidal neovascular membrane, ranibizumab

Bietti's crystalline dystrophy (BCD) is a condition comprising tapetoretinal degeneration with small glittering crystals in the posterior pole, atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroidal sclerosis, sparkling yellow crystals in the superficial paralimbal cornea with an onset in the third decade.[1] Long-term follow-up of this condition is associated with progress in RPE atrophy. We hereby report an interesting case of BCD presenting with choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and successfully treated with intravitreal injections of ranibizumab.

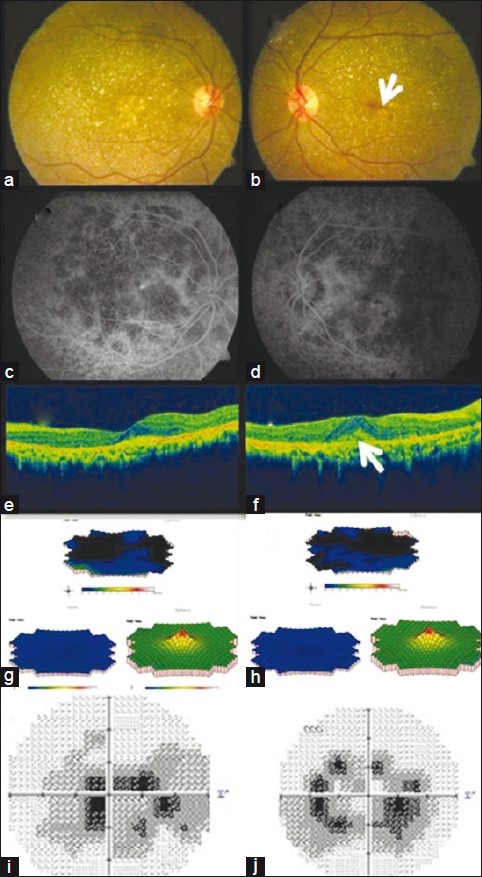

A 33-year-old man presented with complaints of distorted central vision in the left eye of one-week duration. He had similar complaints in the right eye one year ago. He also had night vision problems. There was no significant family history or history of any drug intake. On examination, he had a best corrected Snellen's visual acuity of 6/9; N8 in both the eyes. The anterior segment examination showed paralimbal corneal crystals in both eyes. Fundus examination revealed diffuse RPE alterations with numerous intraretinal crystalline deposits in both eyes suggestive of BCD. A scarred subfoveal CNVM was noted in the right eye [Fig. 1a]. Subretinal hemorrhage with active subfoveal CNVM was noted in the left eye [Fig. 1b]. Fundus fluorescein angiography revealed numerous window defects in both eyes suggestive of RPE atrophy, and subfoveal leakage with blocked fluorescence in the left eye suggestive of active CNVM [Figs. 1c and d]. Spectral domain OCT (Topcon 3D OCT 2000) revealed scarred CNVM in the right eye and subfoveal CNVM with increased retinal thickness and moderately reflective echoes suggestive of hemorrhage in the left eye [Figs. 1e and f].

Figure 1.

Pre-treatment fundus photograph of both eyes (a, b) showed retinal crystals with CNVM. Subretinal hemorrhage was seen in the left eye (arrow). FFA of both eyes (c, d) showed areas of window defects corresponding to areas of the retinal pigment epithelium, and choriocapillaris atrophy with blocked fluorescence in the left eye. SD-OCT of the right eye showed scarring (e). Left eye (f) showed loss of foveal contour with retinal thickness with an active subfoveal CNVM (arrow). mfERG revealed reduced central and paracentral ring responses in both eyes (g, h).Visual field defects were noted on HVF (i, j)

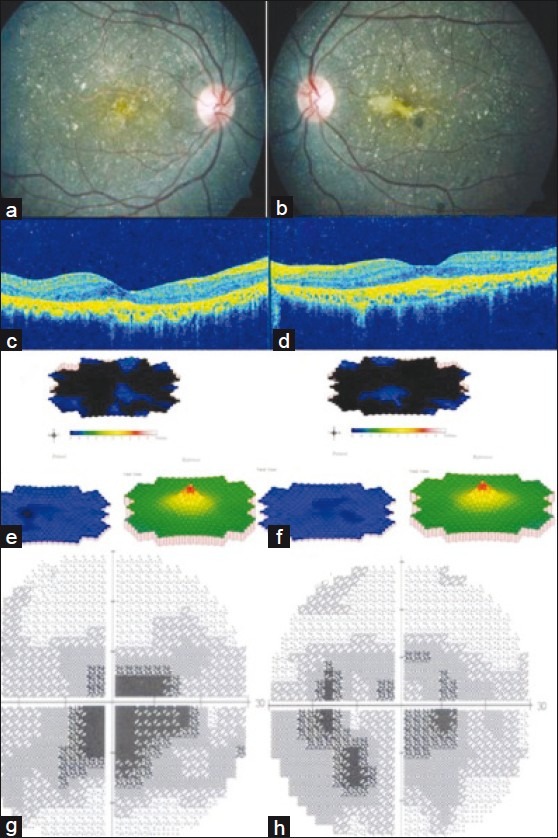

Full-field Electroretingram ERG showed grossly normal photopic and scotopic responses while multifocal ERG revealed grossly reduced central and paracentral ring responses in both eyes [Figs. 1g and h]. Humphrey visual fields 30–2 showed dense central scotoma in both the eyes [Figs. 1i and j]. His serum triglyceride level was found to be 171 mg/dl. Genetic workup was also done and bidirectional sequencing of all eleven exons of CYP4V2 gene did not reveal any pathogenic variation. The patient was explained the nature of his condition. A treatment option of anti-VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) injection was offered to the patient after explaining its roles and limitations for which the patient consented. He was administered three injections of 0.05 mg ranibizumab (Lucentis®; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland; Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA) intravitreally at monthly intervals. At the last follow-up of 12 months after the final injection the patient maintained the same visual acuity and distortion had reduced. Fundus examination showed scarred CNVM in both eyes [Figs. 2a and b] which was confirmed on OCT [Figs. 2c and d]. The multifocal ERG [Figs. 2e and f] and visual fields [Figs. 2g and h] did not show much variation over the period of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Color fundus photograph 12 months after the last injection in the left eye shows scarred choroidal neovascular membrane in the right eye (a) and left eye (b) which is also demonstrated on OCT (c, d). mfERG (e, f) showed grossly reduced central and paracentral responses and central visual field defects were noted on HVF (g, h)

Discussion

BCD is an autosomal recessive disorder due to mutations in the CYP4V2 gene[2] and characterized by crystalline retinal deposits associated with RPE and choriocapillaris atrophy which are represented as areas of prominence of medium and large-sized choroidal vessels on fundus fluorescein angiography.[1] Long-term follow-up of cases of BCD have demonstrated a progression of patients’ symptoms, visual field defects and electrophysiologic results. Mansour et al., have demonstrated a long-term progression of the RPE atrophy.[2] So far only one BCD case has been reported with subfoveal CNVM.[3] Here we report another patient with BCD associated with subfoveal CNVM. Absence of CYP4V2 mutation in this patient needs further evaluation to understand the genetic factors behind CNVM in this patient. The probable reasons for not identifying a variation in CYP4V2 could be due to a variation in the promoter region of CYP4V2, which has not been characterized or the disease could be genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous with more genes that control lipid metabolism being involved. Retinal pigment epithelial dystrophies that are associated with CNVM include Sorsby fundus dystrophy, North Carolina macular dystrophy, Best vitelliform macular dystrophy etc.[4–6] However, to the best of our knowledge no BCD case with CNVM has been reported with complete genotyping of the CYP4V2 gene. We hypothesize that chronic irritation of Bruch's membrane by the crystals may have provoked CNVM in this patient. The efficacy of ranibizumab in the management of CNVM secondary to age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) has been well documented.[7] However, its clinical efficacy in non-ARMD CNVM is yet to be established in a well-designed study. In the presence of active CNVM and visual distortions, a decision was made to treat the eye rather than to observe in a manner similar to a related study.[3] The scarring of CNVM may have been the result of the drug efficacy or natural history. However, the stable visual acuity and disappearance of distortions suggests a possible role of ranibizumab in these rare cases.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wilson DJ, Weleber RG, Klein ML, Welch RB, Green WR. Bietti's crystalline dystrophy. A clinicopathologic correlative study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:213–21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010219026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansour AM, Uwaydat SH, Chan CC. Long term follow up in Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17:680–2. doi: 10.1177/112067210701700434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Tien V, Atmani K, Querques G, Massamba N, Souied EH. Ranibizumab for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in Bietti crystalline retinopathy. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1728–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qi JH, Dai G, Luthert P, Chaurasia S, Hollyfield J, Weber BH, et al. S156C mutation in tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 induces increased angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19927–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leu J, Schrage NF, Degenring RF. Choroidal neovascularisation secondary to Best's disease in a 13-year-old boy treated by intravitreal bevacizumab. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:1723–5. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee DY, Reichel E, Rogers A, Strominger M. Subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in a 3-year-old child with North Carolina macular dystrophy. J AAPOS. 2007;11:614–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell P, Korobelnik JF, Lanzetta P, Holz FG, Prunte C, Schmidt-Erfurth U, et al. Ranibizumab (Lucentis) in neovascular age related macular degeneration: Evidence from clinical trials. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:2–13. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.159160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]