Abstract

A 12-year-old girl, diagnosed of osteogenesis imperfecta, presented with sudden visual loss in the left eye. Investigations revealed an active choroidal neovascular membrane. She underwent treatment with intravitreal Bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 ml). Follow-up at 1 month revealed the development of lacquer crack running through the macula, underlying the fovea. The patient received two re-treatments at 1-month intervals, following which the choroidal neovascularization (CNV) regressed completely. However, further progression of lacquer cracks was noted. At the last follow-up, 6 months following the last injection, the fundus remained stable and vision was maintained at 20/200. Considering the natural history of the disease and the increased risk of rupture of the Bruch's membrane in such eyes, the possible complication of a lacquer crack developing must be borne in mind, before initiating treatment.

Keywords: Bevacizumab, choroidal neovascularization, lacquer crack, osteogenesis imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is an inherited disorder of the connective tissue, resulting from mutations in genes coding for type I collagen.[1] The disease manifests in tissues in which the principal matrix protein is type I collagen, i.e. bone, ligaments, dentin, and sclera. The classic features include multiple bone fractures leading to short stature, deafness and blue sclera. Other features include loose joints (hypermobility), flat feet and poor dentition. More severe forms of OI may develop bowed legs and arms, kyphosis and scoliosis. The ocular manifestations are usually not sight threatening and most commonly consist of blue sclera. Additional ocular findings include decreased ocular rigidity, myopia, glaucoma, keratoconus, corneal opacity, small corneal diameter and congenital Bowman's layer agenesis.[2] The development of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) associated with OI and its response to intravitreal Bevacizumab has not yet been reported. Authors hereby report the development of CNV in a patient with OI that responded to treatment with intravitreal Bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 ml).

Case Report

A 12-year-old girl presented with decreased vision in the right eye since 6 months following penetrating injury, for which primary repair was done elsewhere. Physical examination by Internist revealed OI. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/1000 in the right eye and 20/80 in the left eye. Refractive error was previously documented as –11 DS and –18 DS in the right and left eye, respectively. Examination revealed blue sclera in both eyes. Adherent leucoma with irregular anterior chamber and peripheral anterior synechiae were noted in right eye; fundus evaluation was not possible. Ultrasound was done and keratoplasty advised. Left eye fundus was unremarkable, except myopic appearance. However, she was lost to follow-up and presented again 3.5 years later with sudden diminution of vision in the left eye since 3 days.

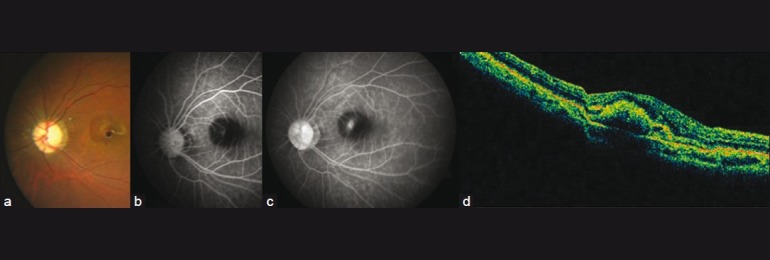

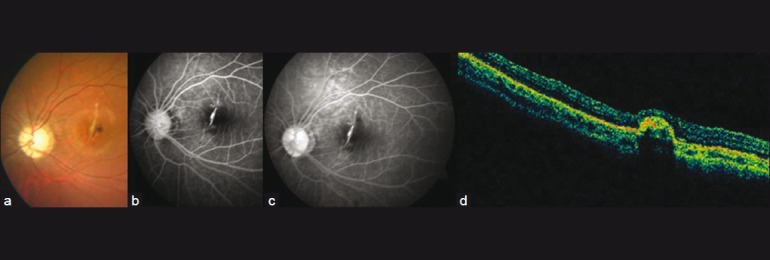

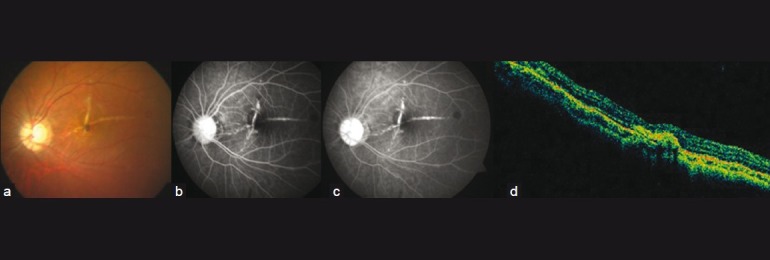

BCVA was 20/1000 in the right eye and 20/630 in the left. There were no additional findings on biomicroscopic examination in the right eye as compared to the initial visit. Fundus evaluation of the left eye showed the presence of a subfoveal choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) [Fig. 1a]. The clinical findings were confirmed on fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT). FFA of the left eye revealed an active subfoveal classic CNVM with profuse leakage. Blocked choroidal fluorescence due to the overlying hemorrhage was also noted [Fig. 1b and c]. OCT revealed subfoveal CNVM and sub-retinal fluid [Fig. 1d]. The treatment options were explained and informed consent was obtained. The patient was treated with intravitreal injections of Bevacizumab (1.25 mg/0.05 ml). At 1-month follow-up, the patient had a BCVA of 20/200 in the treated eye. Fundus evaluation showed a yellow-white linear streak deep to the retinal layers, suggestive of lacquer crack [Fig. 2]. The patient received two re-treatments with intravitreal Bevacizumab at 1-month intervals, following which the CNV regressed. At the last follow-up, 6 months following the last injection, the fundus remained stable [Fig. 3] and visual acuity stabilized at 20/200.

Figure 1.

Active CNV as seen on clinical photography (CP) (a), FFA (b, c) and OCT (d). FFA shows an active subfoveal classic choroidal neovascular membrane with profuse leakage in the late phases. Blocked choroidal fluorescence due to the overlying hemorrhage is also noted. OCT shows subfoveal CNVM and sub-retinal fluid

Figure 2.

CP (a), FFA (b, c) and OCT (d) at 1-month follow-up. CP shows a yellowish streak at the macula concentric to the optic disc, suggestive of a lacquer crack. FFA and OCT confirm the presence of a smaller, yet active CNV

Figure 3.

Color fundus photograph (a), FFA (b, c) and OCT (d) at 6 months’ (final) follow-up. Fundus shows two lacquer cracks almost perpendicular to each other. FFA shows absence of leakage. OCT shows CNV regression with scarring and resolution of sub-retinal fluid

Discussion

High myopia is reported to occur in OI due to axial elongation of the globe and development of posterior staphyloma.[3] The development of CNV in the patient reported here can be attributed to spontaneous ruptures in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)-Bruch's membrane–choriocapillaris complex, secondary to eyeball elongation in highly myopic eyes.[4] The 65-nm striated collagen fibrils of the inner and outer collagenous layers of the Bruch's membrane contain types I, III, and V and the choriocapillaris basement membrane contains collagen type IV.[5] Therefore, the occurrence of CNV can also be attributed to primary abnormality in the collagenous layers of the Bruch's membrane in OI that affects its structural integrity. This is in contrast to the disruptions in the Bruch's membrane that is rendered brittle due to its mineralization and is predisposed to developing cracks as seen in angioid streaks. The play of forces exerted by the extra-ocular muscles on the eye and the tethering effect of the optic nerve to the globe is supposed to modulate the centrifugal orientation of the streaks radially around the disc.

Vision is, however, not affected in most cases of OI. One report describes an ocular form of OI in a South African family of Indian ancestry consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance.[6] The six affected family members had severe skeletal abnormalities and blindness due to corneal opacity, secondary glaucoma, and hyperplasia of the vitreous. There have been additional reports of visual loss in patients of OI due to retinal dialysis and retinal detachment.[7,8] We report the development and treatment of CNV in an eye of a patient with OI with intravitreal Bevacizumab 1.25 mg and an unusual complication of lacquer cracks following such treatment. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy has been described to halt neovascular growth and cause regression of CNV. It is hypothesized that this could have led to RPE contraction placing shearing forces on the RPE. This could have been transmitted to the already weak Bruch's membrane in OI, leading to the development of lacquer cracks as seen in our patient following the injection. It is also conjectured that the development of the lacquer crack occurred as a result of transient increase in intraocular pressure following the intravitreal injection that could have led to rupture of the already fragile Bruch's membrane. There has been a similar recent report on exacerbation of angioid streaks following treatment with Bevacizumab in an eye with CNV.[9]

Considering the natural history of the disease and the increased risk of rupture of the Bruch's membrane in such eyes, the possible complication of a lacquer crack developing must be borne in mind, before initiating treatment.

References

- 1.Kocher MS, Shapiro F. Osteogenesis imperfecta. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:225–36. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evereklioglu C, Madenci E, Bayazit YA, Yilmaz K, Balat A, Bekir NA. Central corneal thickness is lower in osteogenesis imperfecta and negatively correlates with the presence of blue sclera. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2002;22:511–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-1313.2002.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott A, Kashani S, Towler HM. Progressive myopia due to posterior staphyloma in type 1 osteogenesis imperfecta. Int Ophthalmol. 2005;26:167–9. doi: 10.1007/s10792-006-9012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtin BJ. Ocular findings and complications. In: Curtin BJ, editor. The myopias. Philadelphia: Harper and Row; 1985. pp. 277–347. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall GE, Konstas AG, Lee WR. Collagens in ocular tissues. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:515–24. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.8.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beighton P, Winship I, Behari D. The ocular form of osteogenesis imperfecta: a new autosomal recessive syndrome. Clin Genet. 1985;28:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madigan WP, Wertz D, Cockerham GC, Thach AB. Retinal detachment in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1994;31:268–9. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19940701-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliott D, Rezai KA, Dass AB, Lewis J. Management of Retinal Detachment in Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1062–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.7.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen PR, Rishi P, Sen P, Rishi E, Shroff D. Rapid Progression of Angioid Streaks Following Intravitreal Bevacizumab. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009;44:e39–40. doi: 10.3129/i09-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]