Abstract

Background:

Schizophrenia is one of the severe forms of mental illness which demands enormous personal and economical costs. Recent years have attracted considerable interest in the dual problem of depression in schizophrenia and its relation to insight. Most clinicians believe that poor insight in patients with schizophrenia, though problematic for treatment adherence, may be protective with respect to suicide. The assumption is that patients who do not believe that they are ill are less likely to be suicidal. Alternatively, those patients with schizophrenia who recognize and acknowledge the illness will be more of a suicidal nature.

Aim of the Study:

The aim of the study is to find out the correlation between insight and depression in schizophrenic population.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a cross-sectional, single-centred, correlation study done in a total of 60 subjects. Inclusion Criteria - Subjects between 20-60 years, who were diagnosed to have schizophrenia as per International clasification of diseases-10 and who have given written consent to participate in the study. Exclusion Criteria - Subjects who have other diagnosis such as mood disorder, schizoaffective disorder, mental retardation, epilepsy or detectable organic disease and co morbid substance abuse are excluded from the study. Schizophrenics who have acute exacerbation are also excluded. Instruments - For insight assessment, schedule for assessment of insight, a three item rating scale, is used. For depressive symptoms assessment a nine item rating scale, Calgary depression rating scale, is administrated.

Results:

Insight and depression are strongly correlated in schizophrenic population with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.758. The correlation between insight and depression is high in subjects with less duration of illness.

Conclusion:

Better insight was significantly correlated with lower mood. In addition, it suggests that poor insight may protect against depression in the early stages of recovery from schizophrenia. The correlation between insight and depression is high in subjects with less duration of illness.

Keywords: Correlation, depression, insight, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is one of the severe forms of mental illness which demands enormous personal and economical costs. Globally it is estimated that 25 million people have schizophrenia.[1] Recent years have attracted considerable interest in the dual problem of depression in schizophrenia and its relation to insight. Among the primary dimensions of insight, following are included:[2] 1) The awareness of having an illness, its signs and symptoms. 2) The awareness and attribution of recognizable symptoms to that illness. 3) The temporal projection of the insight, distinguishing between actual or retrospective insight, and assuming that insight may vary in extend across different stages of the psychotic process. Nevertheless, beginning with Bleuler, the observation is repeatedly made over the years that a substantial proportion of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia manifest some sort of “depressive-like” symptoms at certain points during their clinical course. Meyer-Gross has written about depression as being a reaction of despair to the psychotic process and a denial of the future.[3] Semradand Eissler, however, has seen depression in schizophrenia as a moment of therapeutic opportunity, when insight and mastery might overcome more primitive defensive psychotic ego states as they receded.[4] Around 50-80% of the patients diagnosed with schizophrenia have been shown to be partially or totally lacking insight into the presence of their mental disorder. Although a causal chain connecting poor insight with poor treatment adherence and thus with poorer outcome and functioning is straight forward, numerous studies investigating correlates and long-term impact of insight have provided differing results. In addition, higher levels of insight in schizophrenia have been associated with depression and hopelessness, but the causal direction of the relationship is unclear and the data are inconclusive.[5] Schizophrenia is a highly stigmatising disorder and many individuals with this diagnosis feel devalued and discriminated.[6] Societal, and sometimes medical, views include the belief that it is a chronic, debilitating condition from which individuals have little chance of recovering.[7] This conceptualization can be threatening and distressing to those given the diagnosis, and is likely to contribute to the high level of depression experienced bymany people with schizophrenia.[8] Indeed, a number of cross-sectional studies support a relationship between higher insight and greater distress, including depression,[9] hopelessness,[10] and suicidality.[11] Most clinicians believe that poor insight in patients with schizophrenia, though problematic for treatment adherence, may be protective with respect to suicide. The assumption is that patients who do not believe that they are ill are less likely to be suicidal. Alternatively, those patients with schizophrenia who recognize and acknowledge the illness will be more suicidal.[12] As per Moore et al., patients with a greater unawareness of their illness had relatively less depressive symptomatology and relatively greater self deception. This relationship was particularly strong for unawareness of the social consequences of a mental disorder. These results suggest that the presence of depressive symptomatology in schizophrenia is related to insight.[13] We have conducted this study from February to May 2011 in Govt. Hospital for Mental Care, Visakhapatnam.

Aim of the study

The aim of the study is to find out the correlation between insight and depression in schizophrenic population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a cross-sectional, single-centred, correlation study done in total of 60 subjects.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects between 20-60 years of are, who are diagnosed to have schizophrenia as per ICD-10 and who have given written consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects who have other diagnosis such as mood disorder, schizoaffective disorder, mental retardation, epilepsy or detectable organic disease and co morbid substance abuse are excluded from the study. Schizophrenics who have acute exacerbation are also excluded.

This is an outpatient-based study, patients, who have come for the follow-up are taken into the study. Each subject is informed about the study in person and their consent was taken. Instruments: For insight assessment, schedule for assessment of insight (SAI),[14] a three item rating scale, is used. The SAI evaluates insight in three dimensions and is used to rate the insight in psychotic illness. For depressive symptoms assessment a nine item rating scale, Calgary depression rating scale, is administrated.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

The statistical analysis is done by using Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) 13.0 version. Descriptive statistics and tests of correlation are used.

In the sample there are 28 males and 32 females. The sample has equal number of both urban and rural residents’ i.e., 30 in each group. There are total 22 unmarried and 38 married people in the sample population. There are 28 literates and 32 illiterates in the sample. The age-wise distribution of the sample is as follows: Below 30 years - 17 members, 30 to 40 years - 21 members, more than 40years - 22 members. The sample consists of 24 patients with duration of illness less than 2 years, 19 patients with duration of illness between 2 years to 5 years and 17 patients have duration of more than five years.

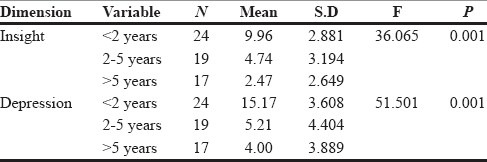

The tables from one to five demonstrate the distribution of sample in different demographic variables such as age, gender, area of residence, marital status and educational status. Table 1 gives the duration of illness in the sample population.

Table 1.

Duration of illness

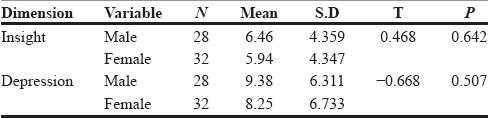

In Table 2 both the insight and depression are more in male population when compared to female population with better mean values.

Table 2.

Gender

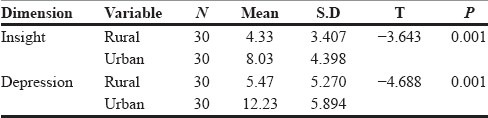

In Table 3 both the depression and insight are more in urban population when compared to rural population.

Table 3.

Area

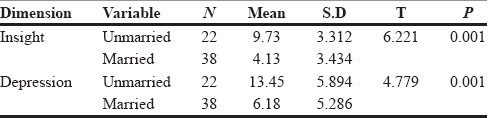

As per Table 4, married patients have lesser insight and lesser depressive ideas than the unmarried patients.

Table 4.

Marital status

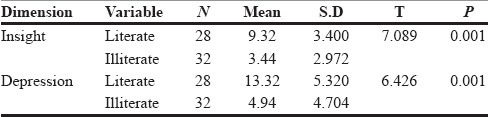

In Table 5, the results are suggestive of higher values of both insight and depression in literates than in illiterates.

Table 5.

Literacy

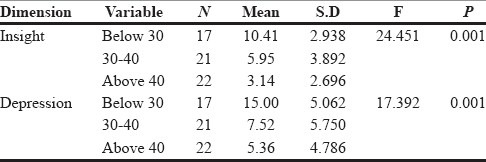

From Table 6, the results are conclusive that as the age increases both insight and depression decreases in schizophrenic patients, as evidenced by the higher mean values of insight and depression in below 30 years age group.

Table 6.

Age

From Table 1, the results are conclusive that as the duration of illness increases both insight and depression decreases in schizophrenic patients, as evidenced by the higher mean values of insight and depression in the group of subjects with duration of illness less than two years.

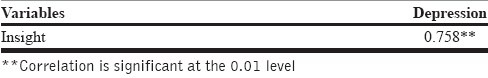

Table 7 gives the correlation between insight and depression in overall sample. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.758 and is suggesting strong correlation between both variables. It is significant at 0.01 level (P value).

Table 7.

Correlation between insight and depression

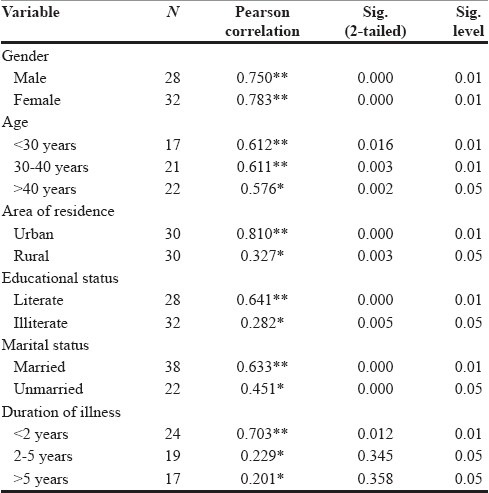

Table 8 shows the strength of correlation between insight and depression in different groups. In both males and females the correlation between insight and depression is strong, as given by the Pearson coefficient more than 0.7 with significance at 0.01 level. The influence of age of patient on the correlation is also well-established, as with increase in the age of the patient the strength of correlation decreases. In less than 30 years age group, Pearson coefficient is 0.612 at a 0.01 significance level, whereas in more than 40 years age group the same is 0.576 at a 0.05 significance level. The residents of urban area have more correlation than rural residents with Pearson coefficients of 0.810 and 0.327 respectively and are significant at 0.01 and 0.05. Educational status of patients has also its influence as literates have more correlation than illiterates with Pearson coefficients of 0.641 and 0.282 and are significant at 0.01 and 0.05 respectively. Patients who are married have a strong correlation than unmarried with Pearson coefficients of 0.633 and 0.451 and are significant at 0.01 and 0.05 respectively. Patients in the early stages of illness have more correlation than at later stages, as evidenced by Pearson coefficients of 0.703, 0.229, 0.201 in <2 years, 2-5 years and >5 years duration of illness groups respectively.

Table 8.

Correlation between insight and depression in different groups

DISCUSSION

The stigma and negative societal views can make the diagnosis of schizophrenia more distressing to the patient and the awareness of illness leads to depressive symptoms in the patient. Poor insight is sometimes seen as just another symptom or manifestation of the disorder.[15] However, main conceptualisation is that poor insight represents an individual response to the diagnosis of schizophrenia and it has a relation to suicidal ideation.[16] Studies have led to hypothesise that there is a chain of causality from insight, to demoralisation, to depression, to suicidality.[11] In our study, there is a strong correlation between insight and depression in schizophrenic population with a Pearson coefficient of 0.758. Our study results are in par with previous literature, which suggests that better insight is directly related to greater distress.[9–11,16]

In a study by Rocca et al.,[17] male gender was associated with an increased severity of depressive symptoms. In contrary to this study our results doesn’t document any difference in the two genders in strength of correlation as both have >0.7 Pearson coefficient. In our study people residing in urban areas have stronger correlation than those in rural areas, explicable by more literacy rate, more exposure and more deficit awareness of the schizophrenic illness. The distress associated with ‘deficit awareness’ is due to the insight of the practical constraints brought about by these deficits.

Previous studies[18,19] have reported that depressive symptoms are less frequent in schizophrenia patients in the chronic period than in the acute period. Studies on first episode psychosis have shown comparable higher levels of insight at baseline (60%): 1) A higher insight during the baseline assessment in a first episode psychosis patient is positively correlated with a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms at this time.[20] 2) A higher degree of insight predicts a higher risk for a subsequent post-psychotic depression, and a higher risk of suicide during the first four years after receiving the diagnosis of psychosis.[21] 3) Approximately 11% of the first episode psychosis patients, present self-harm episodes prior to their first diagnosis with an increased risk associated to male gender, low social class, depression, a longer Duration of untreated psychosis and increased insight.[22] In our study also, the results are suggestive of more correlation as well as higher mean values of insight and depression in early stages of schizophrenic illness. As the duration of illness increases the insight about the illness diminishes and the rate of occurrence of depressive symptoms also falls down. Age of the patients also follows similar trend because most of the people experience the onset of schizophrenic illness when they are young.

In this study, literate population have stronger correlation than the illiterate population, explicable by more deficit awareness but this finding is in contrary to the study of Amador XF et al., who documented that level of education and level of positive and negative symptoms of the illness are unrelated to insight suggesting that deficits in illness awareness are not a consequence of educational background.[23] In this study, married subjects have lesser mean values of insight and depression than unmarried but the correlation between insight and depression is strong in married subjects. This can be explained by the different coping mechanisms used by the patients of schizophrenia. “Preference for positive reinterpretation and growth” coping style[24] correlated with lower distress and with lower symptom awareness in married subjects who generally have a better social support. “Social support-seeking” coping style[24] correlated with greater awareness of illness in unmarried schizophrenic subjects.

CONCLUSIONS

Better insight was significantly correlated with lower mood. In addition, it suggests that poor insight may protect against depression in the early stages of recovery from schizophrenia. The correlation between insight and depression is high in subjects with less duration of illness. There is a positive cross-sectional relationship between insight and depression, but the underlying processes need further clarification.

LIMITATIONS

This is a cross-sectional study and the patients are not followed to measure the impact of insight. The results may not be applied to a large scale population as the sample size is small. Treatment pattern of the patients is not considered. The consideration of the role of coping mechanisms might have yielded more details.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1. The world health report 2001 - Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope.

- 2. Insight in first episode psychosis. Conceptual and clinical consideration: Rafael SegarraEchebarría; Natalia Ojeda del Pozo; ArantzazuZabalaRabadán; Jon GarcíaOrmaza; Javier Peña Lasa; IñakiEguíluzUruchurtu; Miguel Gutiérrez Fraile; Department of Psychiatry, Cruces Hospital, Osakidetza Mental Health System, Vizcaya.

- 3.McGlashan TH, Carpenter WJ., Jr Postpsychotic depression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:231–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770020065011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semrad EV. In: Long-term therapy of schizophrenia: Formulation of the clinical approach, in Psychoneuroses and Schizophrenia. Usdin GP, editor. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1966. pp. 155–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correlates and long-term consequences of poor insight in patients with Schizophrenia. A systematic Review: Tania M. Lincoln1, Eva Lüllmann and Winfried Rief. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickerson FB, Sommerville J, Origoni AE, Ringel NB, Parente F. Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:143–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Corrigan PW. Familiarity with mental illness and social distance from people with schizophrenia and major depression: Testing a model using data from a representative population survey. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:175–82. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulholland C, Cooper S. The symptom of depression in schizophrenia and its management. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6:169–77. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mintz AR, Dobson KS, Romney DM. Insight in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:75–88. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll A, Pantelis C, Harvey C. Insight and hopelessness in forensic patients with schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:169–73. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz RC, Smith SD. Suicidality and psychosis: The predictive potential of symptomatology and insight into illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amador XF, Friedman JH, Kasapis C, Yale SA, Flaum M, Gorman JM. Suicidal Behavior in Schizophrenia and its relationship to awareness of illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1185–88. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.9.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore O, Cassidy E, Carr A, O’Callaghan E. Unawareness of illness and its relationship with depression and self-deception in schizophrenia. Eur J Psychiatry. 1999;14:264–9. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(99)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacPherson R, Jerrom B, Huges A. Relationship between insight, Educational background and cognition in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:718–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuesta MJ, Peralta V. Lack of insight in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:359–66. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owens DG Cunningham, Carroll A, Fattah S, Clyde Z, Coffey I, Johnstone EC. A randomized, controlled trial of a brief interventional package for schizophrenic out-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:362–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocca P, Silvia B, Calvarias P, Marchiaro L, Patria L, Rasetti R, et al. Depressive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Different effects on clinical features. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:304–10. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandelow B, Müller P, Gaebel W, Köpcke W, Linden M, Müller-Spahn F, et al. Depressive syndromes in schizophrenic patients after discharge from hospital. J Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;240:113–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02189981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancon C, Acquier P, Reine G, Barnard D, Addington D. Relationship between depression and psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia during an acute episode and stable period. Schizophr Res. 2001;47:135–40. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crumlish N, Whitty P, Kamali M, Clarke M, Browne S, McTigue O, et al. Early insight predicts depression and attemped suicide after 4 years in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:449–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeedi H, Addington J, Addington D. The association of insight with psychotic symptoms, depression, and cognition in early psychosis: A 3-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2007;89:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey SK, Dean K, Morgan C, Walsh E, Demjaha A, Dazzan P, et al. Self-harm in first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:178–84. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Gorman JM, Endicott J. The Assessment of Insight in Psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:873–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooke M, Peters M, Fannon D, Anantha, Anilkumar PP, Aasen I, et al. Insight, distress and coping styles in schizophrenia: Schizophrenia Research. 2007;94:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]