Abstract

Background

The cell cycle regulator Cyclin D1 is expressed in embryonic retinal progenitor cells (RPCs) and regulates their cell cycle rate and neurogenic output. We report here that Cyclin D1 also has important functions in postnatal retinal histogenesis.

Results

The initial production of Müller glia and bipolar cells was enhanced in Cyclin D1 knockout (Ccnd1−/−) retinas. Despite a steeper than normal rate of depletion of the RPC population at embryonic ages, postnatal Ccnd1−/− retinas exhibited an extended window of proliferation, neurogenesis and gliogenesis. Cyclin D3, normally confined to Müller glia, was prematurely expressed in Ccnd1−/− RPCs. However, Cyclin D3 did not compensate for Cyclin D1 in regulating cell cycle kinetics or neurogenic output.

Conclusions

The data presented in this study along with our previous finding that Cyclin D2 was unable to completely compensate for the absence of Cyclin D1 indicate that Cyclin D1 regulates retinal histogenesis in ways not shared by the other D-cyclins.

INTRODUCTION

During mammalian retinal histogenesis, retinal progenitor cells (RPCs) proliferate extensively and concomitantly give rise to the six major classes of retinal neurons and Müller glia in a temporal order (Rapaport et al., 2004). Controlled progression through the cell cycle is central for this to occur (Levine and Green, 2004). Once committed to undergo cell division, an RPC can produce two RPCs, two postmitotic precursor cells or an RPC and a precursor. Since several cell types (i.e. rod photoreceptors, bipolar interneurons, and Müller glia) are produced during the latter half of the neurogenic interval, proper regulation of the RPC or precursor fate choice in each cell cycle is essential to retain enough RPCs for generating the later born cell types. A combination of extrinsic signaling pathways and intrinsic fate-determining networks are likely to influence the cell cycle machinery, inducing cell cycle progression for RPC-fated cells and cell cycle exit for neuronal or glial precursor-fated cells (Levine and Green, 2004; Cayouette et al., 2006; Agathocleous and Harris, 2009). Therefore, it is important to identify the cell cycle proteins that contribute to the pace and progress of retinal histogenesis.

Cyclin D1 (MGI gene symbol: Ccnd1) is the predominant D-cyclin expressed in RPCs during retinal histogenesis and Ccnd1-knockout (Ccnd1−/−) mice have hypocellular retinas (Fantl et al., 1995; Sicinski et al., 1995; Ma et al., 1998; Das et al., 2009). We recently demonstrated that Ccnd1 inactivation increases cell cycle time in embryonic and neonatal RPCs and enhances their rate of cell cycle exit (Das et al., 2009). We also found that the proportions of precursor populations were changed due to their altered production, underlining the importance of Ccnd1 in generating the correct complement of retinal neurons (Das et al., 2009).

Besides Ccnd1, the other D-cyclin expressed in the retina is Cyclin D3 (MGI gene symbol: Ccnd3). Ccnd3 is not expressed in RPCs during development. Rather, towards the end of histogenesis, it is expressed in newly generated Müller glia precursors and possibly in postnatal RPCs (this study). Western blot analysis of postnatal day 1 (P1) Ccnd1−/− revealed that CCND3 is precociously expressed in the mutant (Tong and Pollard, 2001), which raises the possibility that Ccnd3 could compensate for the Ccnd1 deficiency.

In this study, we characterize the effects of Ccnd1 inactivation on postnatal retinal histogenesis and determine whether Ccnd3 is compensatory for Ccnd1. In spite of the smaller RPC population at birth in the Ccnd1−/− retina, generation of postnatal cell types still occurred, although with altered timing. Unexpectedly, the neurogenic period is extended in the Ccnd1−/− retina, further underscoring the importance of Ccnd1 in regulating RPC proliferation dynamics. We also found that Ccnd3 does not compensate for the Ccnd1 loss, at least up until birth. While these findings indicate that D-cyclins are not absolutely required for cell proliferation or tissue histogenesis, the diversity of cell cycle proteins and complexity of the cell cycle is likely maintained in part because of non-overlapping functions of specific cell cycle proteins and a dependence of progenitor populations on these proteins to coordinate proliferation with production of postmitotic precursors at the appropriate times and rates.

RESULTS

Proliferation persists late in Ccnd1−/− retina development

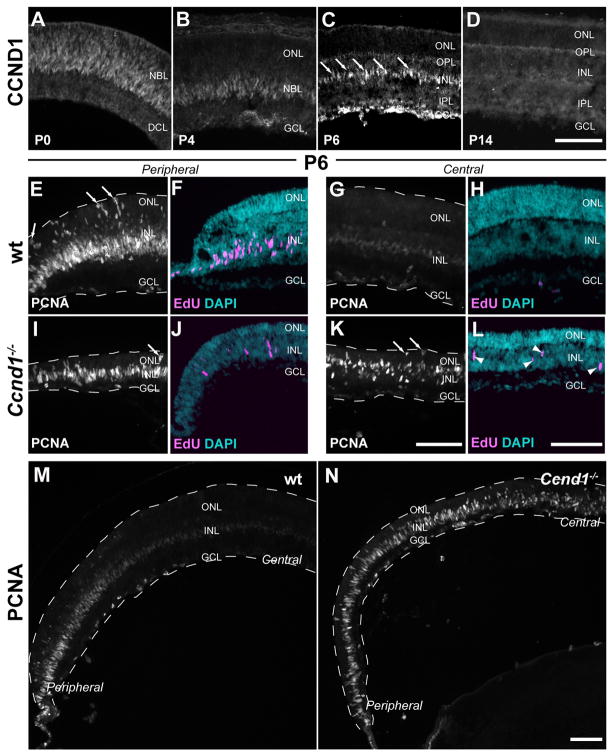

Due to premature cell cycle exit and a lengthening of cell cycle time, Ccnd1−/− RPCs undergo a steeper rate of depletion compared to their wild type counterparts (Das et al., 2009). Therefore, we expected proliferation and neurogenesis to terminate prematurely in the Ccnd1−/− retina during postnatal development. As a first step in determining if this was true, we characterized the normal expression pattern of CCND1 protein from P0 to P14 (Fig. 1A–D; Table 1 lists the complete names and target cell populations of all markers). During this period, CCND1 was expressed in RPCs and the dynamically diminished pattern corresponded with the decline in RPCs associated with the completion of histogenesis. By P6, CCND1 expression was restricted to a row of cells in the central retina (arrows; Fig. 1C). Due to the central to peripheral progression of retinal histogenesis, many CCND1+ cells were present in the peripheral retina (see Fig. 2H). By P14, CCND1+ cells were no longer observed (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Persistent proliferation in the postnatal Ccnd1−/− retina.

(A–D) CCND1 expression in wild type retinas from P0 to P14. CCND1 was expressed in a pattern consistent with RPCs and their temporal depletion, which is complete by P14. Arrows in C denote laminar position of CCND1+ cells. The staining at the edge of the GCL is due to secondary antibody cross-reactivity. (E–L) Proliferation in P6 wild type and Ccnd1−/− retinas. PCNA is a general RPC marker and EdU identifies cells that were in S-phase during the labeling interval (2.5 hours). Arrows in E,I, and K denote PCNA+ mitotic figures; arrowheads in L denote EdU+ cells. Notable differences between the wild type and Ccnd1−/− retinas are the presence of fewer EdU+ cells in the peripheral retina of the mutant (compare F and J) and the persistence of PCNA+ and EdU+ cells in the central retina of the mutant (compare G and H to K and L). (M,N) Wide field views of wild type (M) and Ccnd1−/− retinas (N) reveal the extensive persistence of PCNA+ cells in the mutant at P6. Dashed lines mark the apico-basal boundaries of retina. Abbreviations: DCL, differentiated cell layer; NBL, neuroblast layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bars: 100 μm

Table 1.

Cell Markers

| Marker (host) | Target (molecule name) | Target cells | Dilution factor | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrdU (mouse) | 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine | cells undergoing DNA replication at time of exposure | 100 | BD Biosciences |

| BrdU (rat) | 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine | cells undergoing DNA replication at time of exposure | 100 | Serotec |

| CCND1 (rabbit) | Cyclin D1 | RPCs | 400 | Lab Vision |

| CCND3 (mouse) | Cyclin D3 | Müller glia, (RPCs) | 400 | Santa Cruz |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole | all cell nuclei | 40000 | Sigma |

| EdU | 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine | cells undergoing DNA replication at time of exposure | not applicable | Molecular Probes |

| GS (mouse) | Glutamine Synthetase | Müller glia | 1000 | BD Transduction Labs |

| GFAP (mouse) | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein | reactive Müller glia; astrocytes | 500 | Sigma |

| NR2E3 (rabbit) | Nuclear Receptor subfamily 2, group E, member 3 | rod photoreceptor precursors | 100 | Anand Swaroop |

| PCNA (mouse) | Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen | RPCs | 500 | Dako |

| PKCα (rabbit) | Protein Kinase C, Alpha | rod bipolar cells | 10000 | Sigma |

| POU4F2 (goat ) | POU class 4 Homeobox 2 (Brn3b) | RGC precursors | 50 | Santa Cruz |

| PTF1A (rabbit) | Pancreas Specific Transcription Factor, 1a | amacrine and horizontal cell precursors | 800 | Helena Edlund |

| RCVRN (rabbit) | Recoverin | photoreceptors | 4000 | Chemicon |

| RLBP1 (rabbit) | Retinaldehyde Binding Protein 1 (CRALBP) | Müller glia | 1000 | John Saari |

| RXRγ (rabbit) | Retinoid X Receptor, Gamma | cone photoreceptor precursors, RGCs | 200 | Santa Cruz |

| SOX9 (rabbit) | SRY-box containing gene 9 | Müller glia | 400 | Millipore |

| VSX2 (sheep) | Visual System Homeobox 2 (Chx10) | RPCs, bipolar cells | 400 | Exalpha Biologicals |

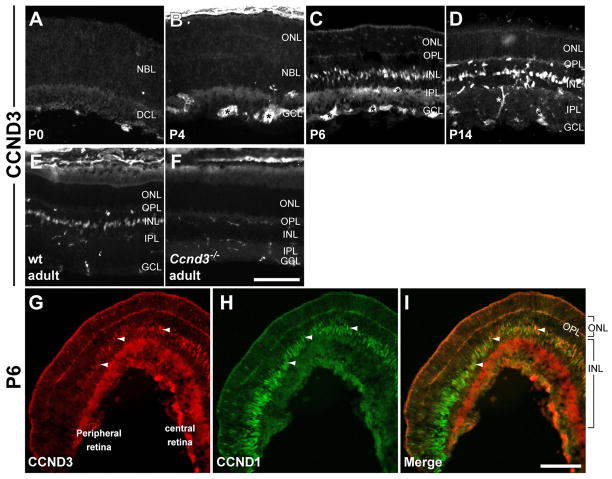

Figure 2. CCND3 expression in the postnatal retina.

(A–E) CCND3 expression in wild type retinas from P0 to adult. CCND3 expression was not detected until P6. Once activated, CCND3 remains expressed into adulthood. The expression pattern was primarily restricted to the INL. Asterisks show examples of secondary antibody cross-reactivity. (F) CCND3 expression is not detected in Ccnd3−/− retina. (G–I) CCND3 (G) and CCND1 (H) expression in the wild type retina at P6 (merged images in I). CCND1 expression is extinguished along the centro-peripheral axis of the retina and CCND3 expression is activated along the same axis in a complementary manner. Arrowheads show examples of cells expressing both proteins. Scale bars: 100 μm

To determine if the RPC population was depleted prematurely in Ccnd1−/− retinas, we analyzed wild type and Ccnd1−/− retinas at P6 for PCNA expression, a comprehensive marker of RPCs (Barton and Levine, 2008). At this age, a large number of PCNA+ cells were present in the peripheral wild type retina (Fig. 1E). In comparable areas of the mutant retina, the PCNA+ RPC layer was thinner (Fig. 1I). That proliferation was reduced in peripheral regions of the Ccnd1−/− retina was further corroborated by the presence of fewer PCNA+ cells at the apical surface where mitosis occurs (arrows, Fig. 1E,I) and fewer cells that incorporated the nucleotide analog EdU during a short labeling interval (Fig. 1F,J). In the central retina of wild type mice, the few cells that expressed PCNA did so at reduced levels (Fig. 1G). EdU+ cells were not detected (Fig. 1H), which suggests that the low level of PCNA expression (Fig. 1G) corresponded with the cessation of proliferation. Surprisingly, bright PCNA+ cells were detected in the central Ccnd1−/− retina with some PCNA+ cells undergoing mitosis (Fig. 1K; arrows point to mitotic cells). Also detected were EdU+ cells (arrowheads in Fig. 1L). In sum, although there are fewer proliferating cells in the peripheral regions of the mutant retina, consistent with a faster rate of RPC depletion, there also exists a population of proliferative cells that persists beyond the normal neurogenic interval in the central retina. This unexpected change in proliferation dynamics is easily discerned at lower magnification (Fig. 1M,N).

CCND3 expression initiates earlier in the Ccnd1−/− retina in RPCs, but does not affect cell cycle rate or precursor cell type output

In other tissues, loss of a D-cyclin is accompanied by ectopic or precocious expression of other D-cyclins (Lam et al., 2000; Solvason et al., 2000; Ciemerych et al., 2002; Cooper et al., 2006; Glickstein et al., 2007). In neonatal Ccnd1−/− retinas, western blots showed that CCND3 protein was precociously expressed (Tong and Pollard, 2001). Thus, it seemed plausible that Ccnd3 may compensate for the absence of Ccnd1 in promoting proliferation.

We first determined the expression pattern of CCND3 at postnatal ages (Fig. 2). In wild type retinas, CCND3 was not observed until P6 (Fig. 2A–C) where it was principally seen in the inner nuclear layer (INL) and faintly in scattered cells in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) of the central retina (Fig. 2C). From P14 onward, CCND3 is expressed in a row of cells in the INL (Fig. 2D–F) which was previously shown to be Müller glia (Dyer and Cepko, 2000; Vazquez-Chona et al., 2009). CCND3 was absent from the peripheral retina (Fig. 2G) indicating that its onset of expression occurs in a central to peripheral wave and is likely the result of the wave of Müller glia genesis. Interestingly, the central to peripheral pattern of CCND3 expression is coincident with the disappearance of CCND1 along the same axis with a few cells expressing both proteins at the overlapping expression boundaries (Fig. 2G–I; arrowheads point to representative double-positive cells). Together, this suggested a developmental change in utilization of D-cyclins from Ccnd1 to Ccnd3.

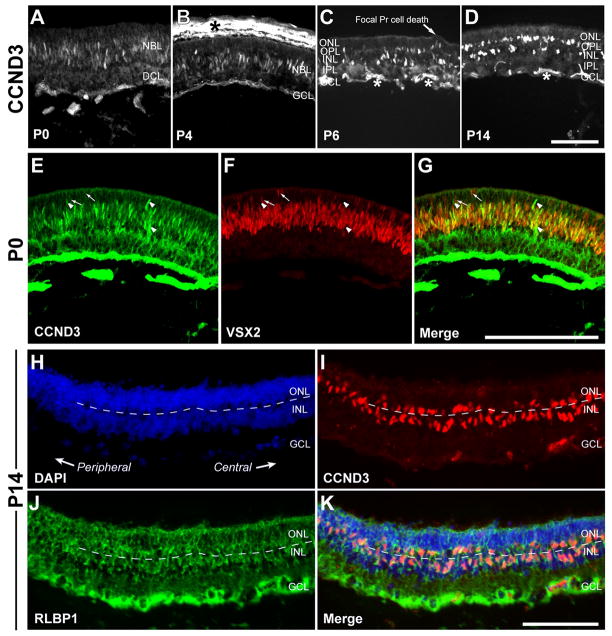

In contrast, we detected CCND3 expression in the neuroblast layer of Ccnd1−/− retinas from P0 onward (Fig. 3A–D) with cells detected as early as E17.5 (data not shown). Colocalization with VSX2 suggested that CCND3 was expressed in Ccnd1−/− RPCs (Fig. 3E–G). At P6, some CCND3+ cells were displaced towards dysplastic regions of the ONL that are associated with extensive photoreceptor cell death (arrow in Fig. 3C; (Ma et al., 1998) and they exhibited an unusual bilayer arrangement in the INL and ONL by P14 (Fig. 3H–K). Regardless of location, the CCND3+ cells are likely to be Müller glia since they also expressed RLBP1 (Fig. 3J,K).

Figure 3. Precocious activation and altered patterns of CCND3 expression in the Ccnd1−/− retina.

(A–D) CCND3 expression was detected by P0 and onward, mainly in the neuroblast layer (NBL). At P6 (C) and P14 (D), CCND3+ cells were also found in the ONL. Arrow in C points to an area of focal cell death in the mutant retina (Ma et al., 1998). Asterisks indicate secondary antibody cross-reactivity. Bright regions beyond the apical retinal boundary (asterisk in B) are due to pigmentation in the retinal pigmented epithelium and choroid. (E–G) CCND3 (E) and VSX2 (F) expression in the Ccnd1−/− retina at P0 (merged images in G). Note the extensive overlap in expression patterns. Arrows point to examples of CCND3−, VSX2+ cells and arrowheads point to CCND3+, VSX2− cells, both of which are rare compared to the double positive cells. (H–K) Triple-labeling with DAPI (H), CCND3 (I), and RLBP1 (J) reveals an unusual bilayer arrangement of CCND3+, RLBP1+ cells in the Ccnd1−/− retina at P14 (merged images in K). Dashed line indicates the boundary between the ONL and INL and corresponds to the outer plexiform layer. Scale bars: 100 μm

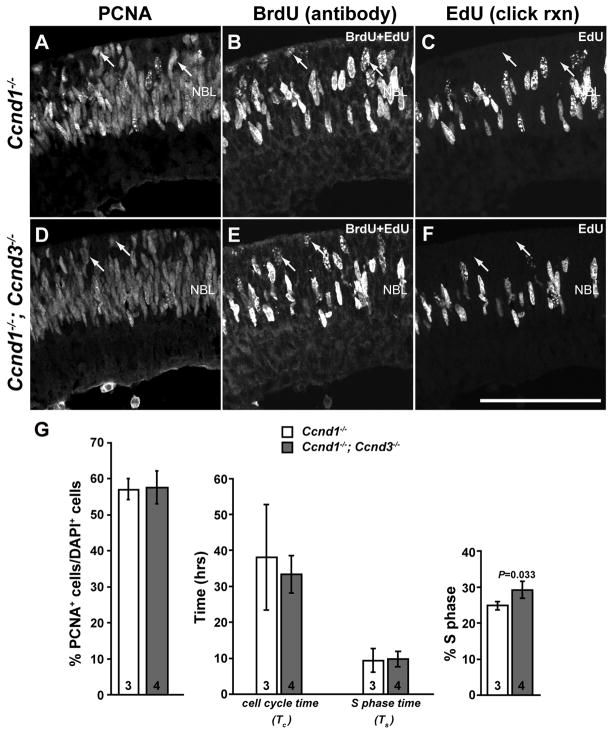

The precocious expression of CCND3 in the Ccnd1−/− retina suggested that genetic compensation could have occurred. To examine this possibility, we generated Ccnd1−/−; Ccnd3−/− double knockout (Dko) animals by crossing the mutant strains. Due to the high mortality rate of Dko neonates (Ciemerych et al., 2002); personal observation), we analyzed the potential compensatory effect of Ccnd3 on RPC proliferation and precursor output at P0.

We previously reported that the average cell cycle time of Ccnd1−/− RPCs is extended (Das et al., 2009). If Ccnd3 has a role in regulating the cell cycle of Ccnd1−/− RPCs, the simplest prediction is that the average cell cycle time would be further increased in Dko RPCs. To assess this, we determined the cell cycle parameters of the newborn Ccnd1−/− and Dko RPC populations with a kinetics-based assay that utilizes two nucleotide analogs in a sequential window-labeling format (Das et al., 2009). PCNA was used to identify RPCs (Fig. 4A,D), BrdU to detect RPCs that were in S-phase during the entire labeling interval (2.5 hr; Fig. 4B,E), and an Alexa-488 tagged-azide to detect RPCs that incorporated EdU during the last 30 minutes of the labeling interval (Fig. 4C,F). The PCNA expression patterns were similar in Dko and Ccnd1−/− retinas (Fig. 4A,D) and quantification of PCNA+ cells showed that the proportions of RPCs were not different between the two mutants (Fig. 4G, left graph). The average cell cycle times (Tc) of the Ccnd1−/− and Dko RPC populations were also similar as were S-phase times (Ts; Fig. 4G, middle graph). The percentages of RPCs in S-phase (Fig. 4G, right graph) were slightly increased in the Dko over Ccnd1−/− (p=0.033). These data indicate that Ccnd3 was not influencing the RPC cell cycle in a signficant manner, despite its precocious expression in the Ccnd1−/− retina.

Figure 4. Ccnd3 does not compensate for Ccnd1 in regulating proliferation.

(A–F) P0 Ccnd1−/− and Ccnd1−/−; Ccnd3−/− retinas were cultured successively in BrdU for 2 hours and EdU for 30 minutes. Sections were triple-labeled for PCNA (A,D), BrdU and EdU (B,E) and EdU only (C,F). Arrows point to RPCs that incorporated BrdU, but not EdU (PCNA+, BrdU+, EdU− ). (G) The percentages of total cells expressing PCNA were unchanged between the two mutants (left graph), as was total cell cycle time (Tc) and S-phase time (Ts; middle graph). The percentage of RPCs in S-phase (right graph) was elevated in the double mutant, but the magnitude of the change was small. Numbers inside bars represent number of animals analyzed and error bars represent standard deviation from the mean. Scale bar: 100 μm.

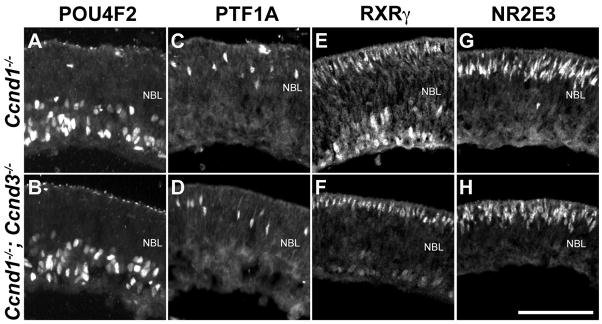

We also assessed whether Ccnd3 influenced the proportions of neuronal precursor cells in Ccnd1−/− retinas. Because CCND3 expression initiated in the Ccnd1−/− retina at approximately E17.5, we did not anticipate changes in early-born retinal cell type precursors generated in the Dko retina compared to the Ccnd1−/− retina. Indeed, expression of the retinal ganglion cell precursor marker POU4F2 (Gan et al., 1999; Qiu et al., 2008), the horizontal/amacrine cell precursor marker PTF1A (Fujitani et al., 2006; Nakhai et al., 2007) were not different between the two mutants (Fig. 5A–D) and this was confirmed with cell counts (data not shown). The expression patterns of the cone photoreceptor precursor marker RXRγ (Mori et al., 2001) and the rod photoreceptor precursor marker NR2E3 (Bumsted O’Brien et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2005) were also similar between the mutants (Fig. 5E–H). Thus, Ccnd3 does not appear to regulate the production of postmitotic precursors from Ccnd1−/− RPCs, at least up to P0.

Figure 5. Ccnd3 does not influence precursor cell type output from Ccnd1−/− RPCs.

P0 Ccnd1−/− and Ccnd1−/−, Ccnd3−/− retinas were stained with antibodies against the RGC precursor marker POU4F2 (A,B), the horizontal and amacrine precursor marker PTF1A (C,D), the RGC and cone photoreceptor precursor marker RXRγ (E,F), and the rod photoreceptor precursor marker NR2E3 (G,H). Scale bar: 100 μm.

Ccnd1 inactivation alters the production of Müller Glia and Bipolar cells

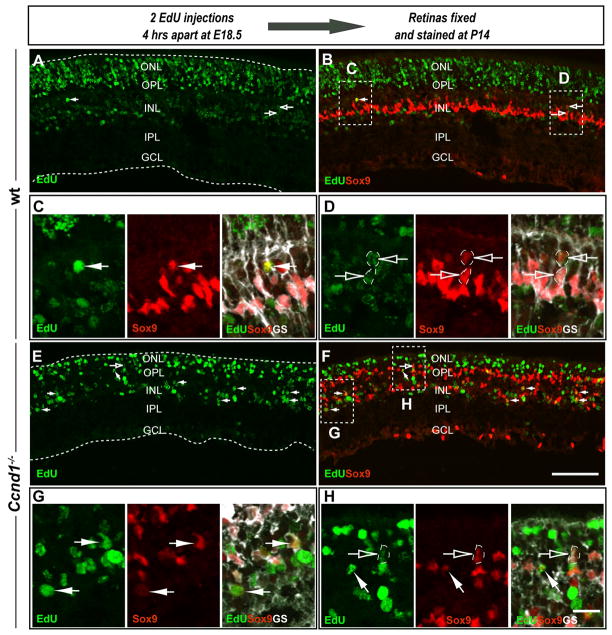

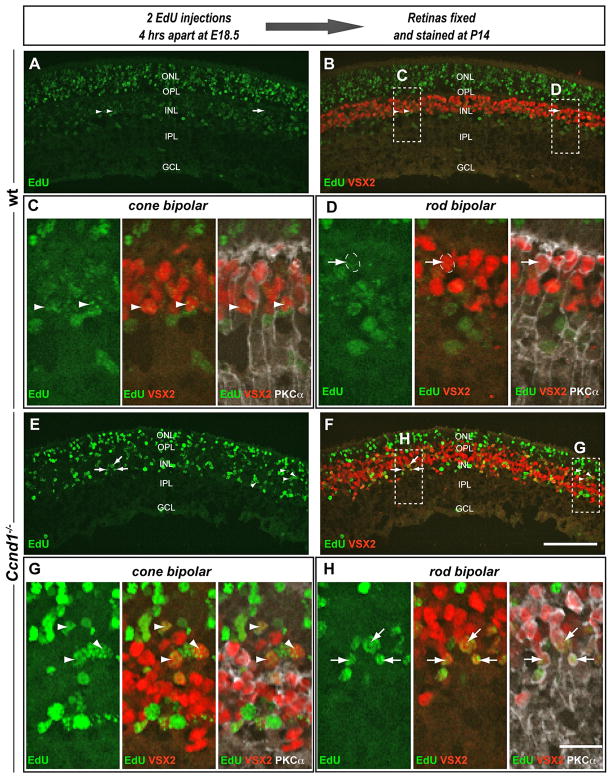

Since Ccnd3 is normally expressed in Müller glia, the early expression of Ccnd3 in the Ccnd1−/− retina could signify precocious gliogenesis. As Müller glia are present in the adult Ccnd1−/− retina (Fig. 3; (Ma et al., 1998) we performed birthdating assays to determine if these cells were born earlier than normal. Pregnant dams were injected at E18.5 with EdU and retinas were harvested from pups at P14 and examined for evidence of EdU+ Müller glia as revealed by co-localization of EdU with SOX9 and/or GS (Fig. 6). RPCs that exited the cell cycle soon after EdU incorporation are predicted to retain most of the label and appear as the most intensely labeled EdU+ cells (EdUhigh). In both wild type and Ccnd1−/− retinal sections, we observed EdU+ cells of varying brightness (Fig. 6A,E). In the central wild type retina, most of the EdUhigh cells were in the ONL (Fig. 6A), consistent with rod photoreceptor production. A few EdUhigh, SOX9+ cells were detected in the INL (closed arrow; Fig. 6A–C), but most of the double labeled cells exhibited weak EdU labeling (EdUlow), suggesting that more than one cell cycle passed before exit (open arrows; Fig. 6A–D). SOX9+ cells, regardless of the intensity of EdU detection expressed GS (closed arrow in Fig. 6C; open arrows in Fig. 6D; (Vardimon et al., 1986). In contrast, Ccnd1−/− retinas showed a higher occurrence of EdUhigh, SOX9+ cells (closed arrows in Fig. 6E–H) and a lower incidence of EdUlow, SOX9+ cells (open arrow in Fig. 6E,F,H). As in the wild type, EdU+, SOX9+ cells also expressed GS, confirming their identity as Müller glia (closed arrows in Fig. 6G; open arrow in Fig. 6H). These data suggest that the rate of Müller glia production was enhanced in the Ccnd1−/− retina, and this was confirmed with cell counts (Table 2). We also birthdated bipolar cells at E18.5 and observed more EdUhigh cells expressing either VSX2 only (cone bipolar cells) or both VSX2 and PKCα (rod bipolar cells) in the mutant retinas than in comparable areas of wild type (Fig. 7; Table 2). The enhanced production of Müller glia and bipolar cells in the Ccnd1−/− mutant suggest a change in the overall temporal dynamics of late retinal histogenesis rather than a selective change in the production of a specific cell type.

Figure 6. Precocious production of Müller glia in the Ccnd1−/− retina.

Retinal cells were birthdated by injecting pregnant animals with 2 doses of EdU at E18.5 and retinas were collected at P14. (A–H) P14 wild type and Ccnd1−/− retina sections were triple labeled for EdU (green), SOX9 (red) and anti-GS (white). Panels B and F show merged images for EdU and SOX9. Insets denoting enlarged areas of retinal sections (C, D, G and H) point to EdU+, SOX9+, GS+ triple labeled cells for further confirmation of Müller glia identity. Closed arrows point to EdUhigh, SOX9+, GS+ cells. Open arrows point to outlined EdUlow, SOX9+, GS+ cells in D and H. Scale bars: 100 μm (A,B,E,F); 20 μm (C,D,G,H).

Table 2.

Quantification of E18.5 birthdated cells

| Cell type | Antibody marker | Percent birthdated cells (EdUhigh, marker+/EdUhigh) *100 | T-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (n) | Ccnd1−/− (n) | |||

| Muller glia | SOX9 | 3.13 ± 1.3 (7) | 14.07 ± 3.13 (8) | p=<0.0001 |

| Cone bipolar | VSX2+, PKC− | 2.86 ± 0.69 (6) | 14.26 ± 6.88 (10) | p=0.00051 |

| Rod bipolar | VSX2+, PKC+ | 0.34 ± 0.53 (6) | 9.15 ± 4.9 (10) | p=0.00028 |

Figure 7. Precocious production of bipolar cells in the Ccnd1−/− retina.

Retinal cells were birthdated by injecting pregnant animals with 2 doses of EdU at E18.5 and retinas were collected at P14. (A–D) Wild type and (E–H) Ccnd1−/− retinal sections were triple labeled for EdU (green), VSX2 (red) and PKCα (white). All images were captured in the central retina. B and F are merged images for EdU and VSX2. Insets denote areas of retinal sections enlarged to point out EdU+, VSX2+, PKCα− cone bipolar cells and/or Müller glia (arrowheads) and EdU+, VSX2+, PKCα+ rod bipolar cells (arrows). Note the abundance of EdUhigh, VSX2+ cells in Ccnd1−/− retinal sections compared to wild type sections. Outlined cell in D is a weakly labeled EdUlow rod bipolar cell. EdUhigh rod bipolar cells were rare in the mutant samples (Table 2) Scale bars: 100 μm (A,B,E,F ); 20 μm (C,D,G,H).

Late proliferating cells in Ccnd1−/− retinas exhibit RPC-like properties

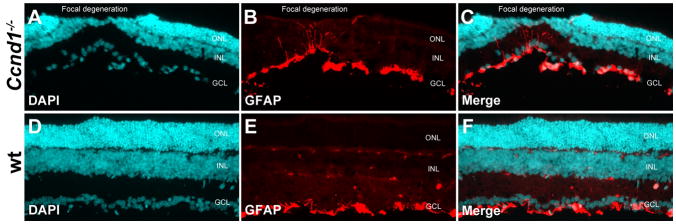

The two most likely sources of persistent proliferation in the late postnatal Ccnd1−/− retina are Müller glia or RPCs. Consistent with Müller glia as the source, their re-entry into the cell cycle is observed in several instances of retinal injury and disease (Dyer and Cepko, 2000; Fischer and Reh, 2003; Kohno et al., 2006; Karl et al., 2008; Thummel et al., 2008; Tackenberg et al., 2009). Müller glia proliferation can also be stimulated with genetic inactivation of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 in the adult retina (Vazquez-Chona et al., 2011). The increased rate of RPC depletion in the Ccnd1−/− retina also argues against RPCs as the source of persistent proliferation, but the slower cell cycle rate in Ccnd1−/− RPCs compared to wild-type (Das et al., 2009) may have counteracted the effect of enhanced cell cycle exit. Distinguishing between Müller glia and RPCs is difficult because their gene expression profiles are similar (Roesch et al., 2008). However, proliferative Müller glia typically adopt a reactive phenotype, which is indicated by elevated GFAP expression, a protein not found in RPCs (Sahel et al., 1990; Humphrey et al., 1997; Taomoto et al., 1998). Furthermore, RPCs would be expected to produce both neurons and glia given their mulitpotential character, a property rarely observed in mammalian Müller glia in vivo (Das et al., 2006; Jadhav et al., 2009; Karl and Reh, 2010). At P14, the GFAP expression pattern in the mutant was similar to wild-type, predominantly confined to astrocytes at the inner boundary of the retina (Fig. 8). The only noticeable difference was that GFAP was associated with regions of focal photoreceptor degeneration (Fig. 8A–C). However, the more important point is that GFAP was not detected in most Müller glia in the mutant retina, suggesting that Müller glia are not the source of proliferation.

Figure 8. GFAP expression in the Ccnd1−/− retina at P14.

(A–C) Ccnd1−/− retinal section stained for DAPI (A) and GFAP (B). Merged images in C. The hypocellular area of the ONL demarcates a zone of photoreceptor degeneration initially described by Ma et al. (1998). In contrast to the pattern of ectopic proliferation, which extends across the retina at earlier ages, GFAP expression within the retina is confined to the dysplastic zones. (D–F) Wild-typeretinal section stained for DAPI (D) and GFAP (E). Merged images in F. GFAP is expressed predominantly along the basal boundary of the retina and is expressed in astrocytes, which is also true in the mutant retina. The punctate staining in the inner and outer plexiform layers is due to secondary antibody cross-reactivity.

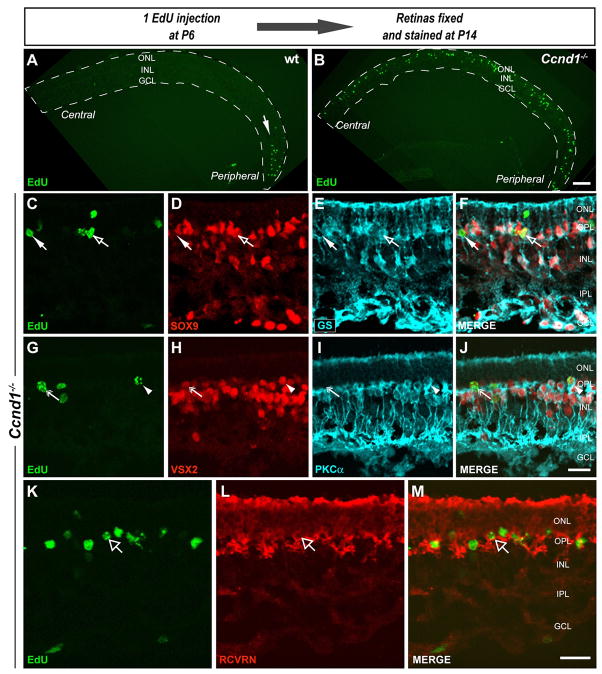

To assess whether the late proliferating cells could be RPCs, we determined whether they were neurogenic by birthdating, in this case with a single injection of EdU at P6 and analysis at P14 (Fig. 9). In contrast to the wild type retina which contained EdU+ cells only in the peripheral retina, EdU+ cells were found in both central and peripheral mutant retina (Fig. 9A,B). Some EdU+ cells were SOX9+ and GS+ identifying them as Müller glia (Fig. 9C–F; open arrows) whereas others were SOX9− and GS− (Fig. 9C–F; closed arrows). Consistent with the latter cohort, some EdU+ cells were VSX2+, PKCα+, identifying them as rod bipolar cells (Fig. 9G–J; arrowhead), or VSX2+, PKCα−, which are presumptive cone bipolar cells (Fig. 9G–J; double headed arrow). Occasional EdU+ cells in the ONL were RCVRN+, indicative of photoreceptors (Fig. 9K–M; open arrow). These observations suggest that the late proliferating cells in Ccnd1−/− retinas, being capable of both neurogenesis and gliogenesis, were more likely to be RPCs or a novel population of Müller glia retaining RPC-like properties.

Figure 9. Late proliferating cells in the Ccnd1−/− retina are neurogenic.

Retinal cells were birthdated by a single EdU injection at P6 and retinas were collected at P14. (A,B) Low power images of P14 wild type and Ccnd1−/− retina sections showing EdU labeled cells. Retinas are located within the dashed lines. (C–F) Representative central regions of Ccnd1−/− retinal sections were triple labeled for EdU, SOX9 and GS to identify birthdated Müller glia. Merged images in F. Open arrow points to a birthdated Müller glial cell (EdUhigh, SOX9+, GS+) and closed arrow points to a birthdated non-Müller glial cell (EdUhigh, SOX9−, GS−). (G–J) Representative central regions of Ccnd1−/− retina sections tripled labeled for EdU, the pan-bipolar marker VSX2, and the rod bipolar marker PKCα to identify birthdated cone and rod bipolar cells. Merged images in J. Double head arrow points to a birthdated cone bipolar cell (EdU+, VSX2+, PKCα−). Arrowhead points to a birthdated rod bipolar cell (EdU+, VSX2+, PKCα+). (K–M) P14 central retina section double-labeled for EdU and general photoreceptor cell marker RCVRN to identify birthdated photoreceptor cells. Open arrow points to a birthdated photoreceptor cell (EdU+, RCVRN+). Scale bars: 100 μm (A,B); 20 μm (C–J; K–M).

DISCUSSION

Altered histogenesis in Ccnd1−/− retinas

A novel finding of this study is that Ccnd1 inactivation resulted in the persistence of proliferating cells beyond the normal period of RPC proliferation. This was unexpected because the Ccnd1−/− RPC population has a steeper rate of depletion during embryonic development (Das et al., 2009). Indeed, in the postnatal peripheral wild type retina, where proliferation was still ongoing, comparable areas of the Ccnd1−/− retinas were visibly deficient in RPCs and proliferation, consistent with premature cell cycle exit. But in the central retina, histogenesis, although terminated in the wild type, was still evident in the mutant.

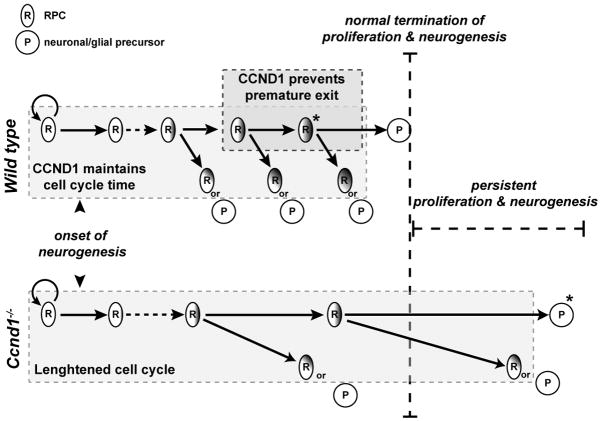

One explanation for the latter observation is that Ccnd1, in reversal to its’ embryonic role, is required for timely cell cycle exit during postnatal histogenesis. This is highly unlikely, however, given that its expression generally promotes cell cycle progression (Motokura and Arnold, 1993; Sherr, 1995; Liao et al., 2007; Lange et al., 2009; Pilaz et al., 2009). A more plausible explanation for why RPCs persist in the Ccnd1−/− retina is because of their slower cell cycle rate and that they continue to proliferate until a certain number of cell cycles is reached or until the extracellular environment no longer supports their proliferation. This may appear to be at odds with our previous findings that Ccnd1−/− RPCs undergo premature cell cycle exit (Das et al., 2009). But since the faster rate of RPC depletion in the mutant is not severe, it is likely that Ccnd1 influences the timing of cell cycle exit in subsets of RPCs with limited proliferative potential at any given stage of histogenesis (Das et al., 2009). This restricted mode of controlling cell cycle exit combined with the slower cell cycle rate could allow for an extended proliferative period (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Model of extended histogenesis in the Ccnd1−/− retina.

A subset of RPCs are restricted in their proliferative potential and depend on Ccnd1 to stay in the cell cycle (dark gray box in wild type). Without Ccnd1, these RPCs prematurely exit from the cell cycle and adopt a precursor fate (asterisk marked cells in wild type and Ccnd1−/−). A larger cohort of RPCs depend on CCND1 to maintain their rate of cell cycle progression (light gray boxes in wild type and Ccnd1−/−). Without Ccnd1, the cell cycle time of mutant RPCs is slower. and linger in the mutant retina. They eventually exit from the cell cycle to make neurons and glia, even after neurogenesis has ceased in the wild type retina.

Our P6 birthdating experiments revealed that the late proliferating cells were capable of producing both late-born retinal neurons and Müller glia and suggests that these cells could be bona-fide RPCs, consistent with the idea of extended histogenesis. We can not exclude the possibilities that proliferating Müller glia are intermingled with RPCs or that the dividing cells are not true RPCs but are rather neurogenic Müller glia, for which there is evidence of in other vertebrates and in mice under certain experimental conditions (Ohta et al., 2008; Bringmann et al., 2009; Jadhav et al., 2009; Karl and Reh, 2010). The likelihood that these cells are Müller glia is low, however, because we did not detect widespread GFAP expression. If these neurogenic cells do indeed arise from Müller glia, the implication is that preventing the reactive state in otherwise proliferative Müller glia may enhance their neurogenic potential.

In addition to the extended window of histogenesis in the Ccnd1−/− retina, we observed precocious production of bipolar cells, and Müller glia. This is significant because while the neurogenic potential of RPCs changes as development progresses (Livesey and Cepko, 2001; Andreazzoli, 2009), our data suggest that similar to early embryonic RPCs, late embryonic RPCs have the potential or competence to produce cell type-specific precursors before they normally generate them, but are prevented from doing so by intrinsic factors such as Ccnd1. One notable difference between the early and late phenotypes, however, is the selective enhanced production rate of certain early cell types versus the general enhanced production rate of most later cell types. It is important to note here, although the production rate of late born cell types were enhanced in the mutant retina, their absolute numbers are probably reduced compared to the wild type. Thus, important open questions are whether Ccnd1 has a direct role in cell fate selection as proposed for the spinal cord (Lukaszewicz and Anderson, 2011), and whether Ccnd1 affects cell type production in a strict cell autonomous manner. These issues can be addressed once tools become available for inactivating Ccnd1 in spatial, temporal, and cell type-specific manners.

A recent study identified Notch1 as a transcriptional target of Ccnd1, and Notch1 expression is duly downregulated in the Ccnd1−/− retina (Bienvenu et al., 2010). Notch signaling has also been implicated in promoting the Müller glia fate (Furukawa et al., 2000). This is superficially counterintuitive to our observation of continued Müller glia production in the Ccnd1−/− retina. However, Notch signaling appears to be important for stabilization of the Müller glia fate and differentiation in postmitotic precursors (Jadhav et al., 2006; Muto et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2011) and this is likely to be distinct from its role downstream of Ccnd1 in mitotic RPCs to maintain a cycling progenitor state. Combined with the observations that the Notch pathway effector Hes1 is still expressed and Notch1 expression is not completely abolished in the Ccnd1−/− retina (Das et al., 2009; Bienvenu et al., 2010), these points offer an explanation for the continued production and differentiation of Müller glia in the Ccnd1−/− retina.

Lack of compensation among D-cyclins in retinal development

In other developing tissues, loss of one D-cyclin can result in the upregulation of another D-cyclin (Lam et al., 2000; Ciemerych et al., 2002; Cooper et al., 2006; Glickstein et al., 2007; Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009). This is also true in the retina since Ccnd3 is expressed earlier than normal in Ccnd1−/− RPCs. In contrast to other regions of the CNS, this did not have any measureable effects on RPC cell cycle rate or precursor production, indicating that Ccnd3 does not compensate for Ccnd1. Ccnd3 may influence production of late born INL cell types and we did observe enhanced production of Müller glia and bipolar cells in the Ccnd1−/− retina. However, immunohistochemical analysis of the developing and mature retina in the Ccnd3−/− mouse failed to uncover any differences in retinal histology between Ccnd3−/− and wild type mice (G.D. and E.M.L, unpublished observations). Whether this reflects reciprocal genetic compensation by Ccnd1 is possible but difficult to address with the germline mutants because of early postnatal lethality in Ccnd1−/−; Ccnd3−/− mice. This could be bypassed by knocking down Ccnd3 in postnatal Ccnd1−/− retinas or by explant culture of postnatal Ccnd1−/−; Ccnd3−/− retinas.

Another possibility is that Cyclin D2 (Ccnd2) compensates when both Ccnd1 and Ccnd3 are inactivated. This is unlikely, however, because Ccnd2 does not appear to be upregulated in the Ccnd1−/−; Ccnd3−/− double knockout retina and the patterns of BrdU incorporation in the Ccnd1−/−;Ccnd2−/−; Ccnd3−/− triple knockout and Ccnd1−/− single knockout retinas are similar (Ciemerych et al., 2002; Kozar et al., 2004). We also found that Ccnd2, when expressed from the Ccnd1 locus, is not sufficient to completely restore retinal development (Das et al., 2009). It is therefore possible that in addition to potential differences in expression characteristics, the failure of Ccnd3 and Ccnd2 to compensate for the Ccnd1 deficiency is because Ccnd1 has functions that are not shared by the other D-cyclins and may be independent of its role in the cell cycle, such as by acting as a transcriptional regulator (Bienvenu et al., 2010).

Conclusion

Our studies support the hypothesis that Ccnd1 and to a more general extent, the D-cyclins, are not absolutely required for retinal histogenesis to occur. Despite this, Ccnd1 is required for the proper execution of the histogenic program by regulating neurogenic output throughout retinal development and contributing to the timing of when histogenesis is terminated. Our data suggest that Ccnd1 accomplishes this by regulating both the rate of cell cycle progression and timing of cell cycle exit in RPCs. Whether Ccnd1 also regulates neurogenic output by other mechanisms such as by directly controlling cell fate decisions independent of its roles in cell cycle regulation still remains to be determined.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Ccnd1−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Ccnd3−/− mice were kindly provided by Piotr Sicinski (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) and Iannis Aifantis (New York University Medical Center, New York, NY). The noon of the day a vaginal plug was observed was designated E0.5. Genotyping was done as previously described (Sicinski et al., 1995; Sicinska et al., 2003). All animal use and care was conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and set forth in the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals.

Immunohistochemistry and image analysis

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry were done as previously described (Clark et al., 2008; Das et al., 2009). Radial cryosections through the retina were cut at a thickness of 10 μm. Markers are listed in Table 1. Sections were analyzed by epi-fluorescence using a Nikon E-600 microscope and images captured in gray scale mode with a Spot-RT slider CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI, USA). Confocal images were scanned using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope. Color (RGB) images were assembled from individual monochrome channels using Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The levels function was used to adjust the digital images to be consistent with visual observations.

Window-labeling using BrdU and EdU to measure cell cycle times

P0 Retinas with lens attached were dissected and cultured for 2.5 hours and sequentially exposed to two thymidine analogs for defined intervals. BrdU was added to the culture medium for the first 2 hours and replaced with EdU for the final 30 minutes. The BrdU antibodies detected both BrdU and EdU. EdU was specifically detected using the Click-iT Reaction (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA; (Buck et al., 2008). PCNA was used to identify RPCs in all phases of the cell cycle (Barton and Levine, 2008). Cell counts and derivation of cell cycle parameters were done as previously described (Das et al., 2009).

Birthdating assays and quantification

Retinal cells were birthdated by EdU injections at the indicated ages. For late embryonic birthdating (E16.5–E18.5), pregnant mice were injected twice, 4 hours apart with EdU (10 mM stock in H20: 25 mg/gm of body weight injected). For postnatal birthdating (P6–P10), each individual animal was injected with a single dose of EdU (10 mM stock in H20: 50 mg/gm of body weight injected). All animals were sacrificed and retinal tissue was harvested at P14.

Birthdated cells were identified as being co-labeled for a cell-specific marker and EdU (Table 1). Bright EdU+ (EdUhigh) cells were in all likelihood to have exited the cell cycle within one or two cell cycles after EdU incorporation.

To quantify birthdated cells, single optical sections were captured on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope. Identical pre-image capture settings were used for experimental and control sections. To define the subset of EdUhigh cells, the following image enhancements were performed in ImageJ (NIH, version 10.2). Captured images were first converted to a 8-bit grayscale format. The histograms of EdU signal were then normalized to the maximum range available (0–255 for 8-bit images) using the ‘Enhance Contrast’ function. This operation ‘stretched’ EdU expression histograms from both genotypes to the same range by applying a linear algorithm and made subsequent thresholding of relevant ‘bright’ EdUhigh cells equivalent across comparable images. A defined constant threshold (200–255) was then applied to these images, converting pixels with brightness values below 200 to ‘white’ backgound and pixels with values above 200 to ‘black’ EdU signal. In Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) the processed image layer was overlaid with the corresponding cell type specific marker images (e.g, SOX9, VSX2, PKCα). EdUhigh cells that co-expressed these markers in the relevant combinations were then manually counted. The percent birthdated cells was calculated by the following formula: [(EdUhigh, marker+cells / EdUhigh cells) *100] and was represented as a percentage of the EdUhigh cell population ± standard deviation. For E18.5 birthdating, retinal tissue from two wild type and two Ccnd1−/− animals were included. Images were captured from non-contiguous tissue sections and each section was treated as N=1. Birthdating counts from experimental and control samples were compared by performing Students’ t-test using Kaleidagraph statistical and graphing software (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA). The data is represented in Table 2.

Bullet Points.

Cyclin D1 is expressed in postnatal retinal progenitors

Fewer RPCs in Cyclin D1−/− retina, but proliferation persists past the normal developmental period

Cyclin D3 is precociously expressed in Cyclin D1−/− RPCs but doesn’t compensate for loss of Cyclin D1

Altered production of late-born retinal cell types in Cyclin D1−/− retina

Developmental timing of retinal histogenesis depends on aspects of Cyclin D1 function that are not shared by other D-cyclins

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: National Eye Insitute: R01-EY013760 and American Recovery and Reinvestment Act; Research to Prevent Blindness: Sybil Harrington Scholar Award and unrestricted funds to the John A. Moran Eye Center

We wish to thank members of the Levine and Fuhrmann laboratories, especially Felix Vazquez-Chona for his insight and help during the project. We are also grateful to Iannis Aifantis, Helena Edlund, John Saari, Piotr Sicinski, and Anand Swaroop for generously providing mice and reagents. This research was completed in partial fulfillment of a doctoral thesis (G.D.)

References

- Agathocleous M, Harris WA. From progenitors to differentiated cells in the vertebrate retina. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:45–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreazzoli M. Molecular regulation of vertebrate retina cell fate. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2009;87:284–295. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KM, Levine EM. Expression patterns and cell cycle profiles of PCNA, MCM6, cyclin D1, cyclin A2, cyclin B1, and phosphorylated histone H3 in the developing mouse retina. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:672–682. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu F, Jirawatnotai S, Elias JE, Meyer CA, Mizeracka K, Marson A, Frampton GM, Cole MF, Odom DT, Odajima J, Geng Y, Zagozdzon A, Jecrois M, Young RA, Liu XS, Cepko CL, Gygi SP, Sicinski P. Transcriptional role of cyclin D1 in development revealed by a genetic-proteomic screen. Nature. 2010;463:374–378. doi: 10.1038/nature08684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann A, Iandiev I, Pannicke T, Wurm A, Hollborn M, Wiedemann P, Osborne NN, Reichenbach A. Cellular signaling and factors involved in Muller cell gliosis: neuroprotective and detrimental effects. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:423–451. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck SB, Bradford J, Gee KR, Agnew BJ, Clarke ST, Salic A. Detection of S-phase cell cycle progression using 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation with click chemistry, an alternative to using 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine antibodies. Biotechniques. 2008;44:927–929. doi: 10.2144/000112812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumsted O’Brien KM, Cheng H, Jiang Y, Schulte D, Swaroop A, Hendrickson AE. Expression of photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor NR2E3 in rod photoreceptors of fetal human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2807–2812. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayouette M, Poggi L, Harris WA. Lineage in the vertebrate retina. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Rattner A, Nathans J. The rod photoreceptor-specific nuclear receptor Nr2e3 represses transcription of multiple cone-specific genes. J Neurosci. 2005;25:118–129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3571-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciemerych MA, Kenney AM, Sicinska E, Kalaszczynska I, Bronson RT, Rowitch DH, Gardner H, Sicinski P. Development of mice expressing a single D-type cyclin. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3277–3289. doi: 10.1101/gad.1023602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AM, Yun S, Veien ES, Wu YY, Chow RL, Dorsky RI, Levine EM. Negative regulation of Vsx1 by its paralog Chx10/Vsx2 is conserved in the vertebrate retina. Brain Res. 2008;1192:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AB, Sawai CM, Sicinska E, Powers SE, Sicinski P, Clark MR, Aifantis I. A unique function for cyclin D3 in early B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:489–497. doi: 10.1038/ni1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das AV, Mallya KB, Zhao X, Ahmad F, Bhattacharya S, Thoreson WB, Hegde GV, Ahmad I. Neural stem cell properties of Muller glia in the mammalian retina: regulation by Notch and Wnt signaling. Dev Biol. 2006;299:283–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G, Choi Y, Sicinski P, Levine EM. Cyclin D1 fine-tunes the neurogenic output of embryonic retinal progenitor cells. Neural Dev. 2009;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer MA, Cepko CL. Control of Muller glial cell proliferation and activation following retinal injury. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:873–880. doi: 10.1038/78774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantl V, Stamp G, Andrews A, Rosewell I, Dickson C. Mice lacking cyclin D1 are small and show defects in eye and mammary gland development. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2364–2372. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Reh TA. Potential of Muller glia to become neurogenic retinal progenitor cells. Glia. 2003;43:70–76. doi: 10.1002/glia.10218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujitani Y, Fujitani S, Luo H, Qiu F, Burlison J, Long Q, Kawaguchi Y, Edlund H, MacDonald RJ, Furukawa T, Fujikado T, Magnuson MA, Xiang M, Wright CV. Ptf1a determines horizontal and amacrine cell fates during mouse retinal development. Development. 2006;133:4439–4450. doi: 10.1242/dev.02598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Mukherjee S, Bao ZZ, Morrow EM, Cepko CL. rax, Hes1, and notch1 promote the formation of Muller glia by postnatal retinal progenitor cells. Neuron. 2000;26:383–394. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L, Wang SW, Huang Z, Klein WH. POU domain factor Brn-3b is essential for retinal ganglion cell differentiation and survival but not for initial cell fate specification. Dev Biol. 1999;210:469–480. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickstein SB, Moore H, Slowinska B, Racchumi J, Suh M, Chuhma N, Ross ME. Selective cortical interneuron and GABA deficits in cyclin D2-null mice. Development. 2007;134:4083–4093. doi: 10.1242/dev.008524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey MF, Chu Y, Mann K, Rakoczy P. Retinal GFAP and bFGF expression after multiple argon laser photocoagulation injuries assessed by both immunoreactivity and mRNA levels. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:361–369. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav AP, Cho SH, Cepko CL. Notch activity permits retinal cells to progress through multiple progenitor states and acquire a stem cell property. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18998–19003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608155103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav AP, Roesch K, Cepko CL. Development and neurogenic potential of Muller glial cells in the vertebrate retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl MO, Hayes S, Nelson BR, Tan K, Buckingham B, Reh TA. Stimulation of neural regeneration in the mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19508–19513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807453105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl MO, Reh TA. Regenerative medicine for retinal diseases: activating endogenous repair mechanisms. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno H, Sakai T, Kitahara K. Induction of nestin, Ki-67, and cyclin D1 expression in Muller cells after laser injury in adult rat retina. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:90–95. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozar K, Ciemerych MA, Rebel VI, Shigematsu H, Zagozdzon A, Sicinska E, Geng Y, Yu Q, Bhattacharya S, Bronson RT, Akashi K, Sicinski P. Mouse development and cell proliferation in the absence of D-cyclins. Cell. 2004;118:477–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam EW, Glassford J, Banerji L, Thomas NS, Sicinski P, Klaus GG. Cyclin D3 compensates for loss of cyclin D2 in mouse B-lymphocytes activated via the antigen receptor and CD40. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3479–3484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange C, Huttner WB, Calegari F. Cdk4/cyclinD1 overexpression in neural stem cells shortens G1, delays neurogenesis, and promotes the generation and expansion of basal progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine EM, Green ES. Cell-intrinsic regulators of proliferation in vertebrate retinal progenitors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao DJ, Thakur A, Wu J, Biliran H, Sarkar FH. Perspectives on c-Myc, Cyclin D1, and their interaction in cancer formation, progression, and response to chemotherapy. Crit Rev Oncog. 2007;13:93–158. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v13.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:109–118. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewicz AI, Anderson DJ. Cyclin D1 promotes neurogenesis in the developing spinal cord in a cell cycle-independent manner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11632–11637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106230108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Papermaster D, Cepko CL. A unique pattern of photoreceptor degeneration in cyclin D1 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9938–9943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P, Mark M. Systematic immunolocalization of retinoid receptors in developing and adult mouse eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1312–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motokura T, Arnold A. Cyclin D and oncogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto A, Iida A, Satoh S, Watanabe S. The group E Sox genes Sox8 and Sox9 are regulated by Notch signaling and are required for Muller glial cell development in mouse retina. Exp Eye Res. 2009;89:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhai H, Sel S, Favor J, Mendoza-Torres L, Paulsen F, Duncker GI, Schmid RM. Ptf1a is essential for the differentiation of GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine cells and horizontal cells in the mouse retina. Development. 2007;134:1151–1160. doi: 10.1242/dev.02781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BR, Ueki Y, Reardon S, Karl MO, Georgi S, Hartman BH, Lamba DA, Reh TA. Genome-wide analysis of Muller glial differentiation reveals a requirement for Notch signaling in postmitotic cells to maintain the glial fate. PloS one. 2011;6:e22817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta K, Ito A, Tanaka H. Neuronal stem/progenitor cells in the vertebrate eye. Dev Growth Differ. 2008;50:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilaz LJ, Patti D, Marcy G, Ollier E, Pfister S, Douglas RJ, Betizeau M, Gautier E, Cortay V, Doerflinger N, Kennedy H, Dehay C. Forced G1-phase reduction alters mode of division, neuron number, and laminar phenotype in the cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21924–21929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909894106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu F, Jiang H, Xiang M. A comprehensive negative regulatory program controlled by Brn3b to ensure ganglion cell specification from multipotential retinal precursors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3392–3403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0043-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport DH, Wong LL, Wood ED, Yasumura D, LaVail MM. Timing and topography of cell genesis in the rat retina. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:304–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch K, Jadhav AP, Trimarchi JM, Stadler MB, Roska B, Sun BB, Cepko CL. The transcriptome of retinal Muller glial cells. J Comp Neurol. 2008;509:225–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.21730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahel JA, Albert DM, Lessell S. Proliferation of retinal glia and excitatory amino acids. Ophtalmologie. 1990;4:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayana A, Kaldis P. Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms. Oncogene. 2009;28:2925–2939. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Mammalian G1 cyclins and cell cycle progression. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1995;107:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicinska E, Aifantis I, Le Cam L, Swat W, Borowski C, Yu Q, Ferrando AA, Levin SD, Geng Y, von Boehmer H, Sicinski P. Requirement for cyclin D3 in lymphocyte development and T cell leukemias. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Parker SB, Li T, Fazeli A, Gardner H, Haslam SZ, Bronson RT, Elledge SJ, Weinberg RA. Cyclin D1 provides a link between development and oncogenesis in the retina and breast. Cell. 1995;82:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solvason N, Wu WW, Parry D, Mahony D, Lam EW, Glassford J, Klaus GG, Sicinski P, Weinberg R, Liu YJ, Howard M, Lees E. Cyclin D2 is essential for BCR-mediated proliferation and CD5 B cell development. Int Immunol. 2000;12:631–638. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackenberg MA, Tucker BA, Swift JS, Jiang C, Redenti S, Greenberg KP, Flannery JG, Reichenbach A, Young MJ. Muller cell activation, proliferation and migration following laser injury. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1886–1896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taomoto M, Nambu H, Senzaki H, Shikata N, Oishi Y, Fujii T, Miki H, Uyama M, Tsubura A. Retinal degeneration induced by N-methyl-N-nitrosourea in Syrian golden hamsters. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:688–695. doi: 10.1007/s004170050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel R, Kassen SC, Montgomery JE, Enright JM, Hyde DR. Inhibition of Muller glial cell division blocks regeneration of the light-damaged zebrafish retina. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:392–408. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W, Pollard JW. Genetic evidence for the interactions of cyclin D1 and p27(Kip1) in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1319–1328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1319-1328.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardimon L, Fox LE, Moscona AA. Developmental regulation of glutamine synthetase and carbonic anhydrase II in neural retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:9060–9064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Chona FR, Clark AM, Levine EM. Rlbp1 promoter drives robust Muller glial GFP expression in transgenic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3996–4003. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Chona FR, Swan A, Ferrell WD, Jiang L, Baehr W, Chien WM, Fero M, Marc RE, Levine EM. Proliferative reactive gliosis is compatible with glial metabolic support and neuronal function. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]