Abstract

The role of iron in surface-mediated formation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) from 2-chlorophenol (2-MCP) was investigated over the temperature range of 200 to 550°C under oxidative conditions. In order to compare and contrast with previous work on copper and ferric oxide-mediated pyrolysis of 2-MCP, identical reaction conditions were maintained (50 ppm 2-MCP, model fly-ash particles containing 5% Fe2O3 on silica). Observed products included dibenzo-p-dioxin (DD), 1-monochlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (1-MCDD), dibenzofuran (DF), 4,6-dichlorodibenzofuran (4,6-DCDF), 2,4– and 2,6-dichlorophenol, 2,4,6-trichlorophenol, quinone, catechol, chloro-o-quinone, chlorocatechol and polychlorinated benzenes. Yields of DD and 1-MCDD were 2 and 5 times higher than under pyolysis conditions, respectively. Although 4,6-DCDF was the major PCDD/F product formed with a yield that was 2.5x greater than under pyrolysis, the yield of non-chlorinated DF, which was the dominant PCDD/F product under pyrolysis, decreased by a factor of 3. Furthermore, the ~2x higher yield of PCDDs under oxidative conditions resulted in a PCDD to PCDF ratio of 0.75 compared to a relatively low ratio of 0.39 previously observed under pyrolytic conditions.

Keywords: iron oxide, PCDD/F, 2-monochlorophenol, precursor pathway, combustion pollutant

Introduction

Formation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs) from thermal processes and combustion sources have been widely studied (Karasek and Dickson, 1987; Altwicker et al., 1990; Huang and Buekens, 1995; Brzuzy and Hites, 1996; Thomas and Spiro, 1996; Fiedler, 1998; 2001). Chlorophenols and chlorobenzenes have been identified as the most direct precursors in essentially all proposed routes of formation of PCDD/Fs (Buser, 1979; Shaub and Tsang, 1983; Dickson and Karasek, 1987; Ballschmiter et al., 1988; Born et al., 1989; Mulholland et al., 2001). Depending on the reaction temperature, two general pathways have been proposed: i) homogeneous gas phase reactions involving specific precursors in the post-flame, thermal zone at 500 - 800 °C (Sidhu et al., 1995; Yang, 1998; Evans and Dellinger, 2005a) and ii) heterogeneous surface catalyzed reactions typically occurring at 200 - 400 °C in the post-flame, cool zone of combustors and flue gas treatment device (Dickson et al., 1989; Altwicker et al., 1990; Ghorishi and Altwicker, 1995). Of these two models, gas phase formation pathway is estimated to account for about 30% of the total PCDD/F emissions (Lanier, 1990; Altwicker, 1991), with surface catalyzed reactions being responsible for the remaining 70%.

The surface reaction mechanisms can be subdivided into: a) de novo formation, in which residual carbon in contact with transition metals in fly ash undergoes oxidation and chlorination reactions to liberate PCDD/F from the carbon matrix (Huang and Buekens, 1996; Stieglitz, 1998) and b) transition-metal catalyzed coupling reactions of chemically similar aromatic precursors such as chlorophenols and chlorobenzenes (Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003a; Nakka, 2004). Among the transition metal species found in native fly ash, copper and iron have been identified to play the most active role in PCDD/F formation (Gullett et al., 1990; Olie et al., 1998), with copper oxides and copper chlorides receiving more attention than its corresponding iron compounds. Probably as a result of iron being highly oxidative above 500 °C, research on the role of iron has largely overlooked the formation of PCDD/Fs and focused mainly on their destruction (Weber et al., 2002; Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003b; Chang et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). However, being redox active and the most abundant transition metal in fly ash, iron can make significant contributions to formation of PCDD/F below 400 °C (Kasai, 1999; Kasai, 2000; Ryan and Altwicker, 2004). We have previously demonstrated (Lomnicki et al., 2008; Vejerano et al., 2011) transition metal ions, including iron oxide, can mediate the formation of surface-associated phenoxyl radicals, which subsequently undergo further reactions to yield PCDD/Fs and other products. In our recent manuscript on iron oxide mediated reactions of 2-MCP under pyrolytic conditions, the PCDD/F yields were 2.5x higher than the yield observed for copper oxide under identical conditions (Nganai et al., 2009).

In this paper we report the results of oxidative thermal degradation of 2-MCP as a model precursor over a surface of iron oxide supported on a silica substrate. The surface-mediated 2-MCP precursor reactions were studied from 200 to 550 °C at conditions identical to those used in our previously reported studies of PCDD/F formation for pyrolysis of 2-MCP and 1,2-dichlorobenzene. Although these conditions represent a less than perfect model in relation to a much wider range of fly ash compositions observed in full-scale incinerators, the conditions in this study are comparable to those used in the scientific literature and allow a direct comparison and comprehensive analysis of the role of iron oxide in formation of PCDD/Fs as a function of air/fuel ratio.

1. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The method of incipient wetness was used to prepare the iron-rich model fly-ash material (Fe-MFAM), which served as a model system for combustion-generated, iron-rich fly-ash. A water solution of iron (III) nitrate (Aldrich) was used to prepare 5% iron (III) oxide on silica. Silica gel powder (Aldrich, grade 923 100-200 mesh) was introduced into the solution of iron (III) nitrate in the amount for incipient wetness to occur. The sample was allowed to age for 24 hr at room temperature and dried at 120 and sieved to a mesh size of 100-120, which corresponds to a particle size of 125-150 microns.

The System for Thermal Diagnostic studies (STDS) (Rubey and Grant, 1988) was used to investigate the 5% Fe2O3/silica catalyzed oxidation of 2-MCP. The STDS consists of a thermal reactor located in a high-temperature furnace housed within a GC oven that facilitates precise temperature control as well as sample introduction. A computer-interfaced control module is used to set and monitor all experimental parameters. A high resolution GC-MS is interfaced in-line with the thermal reactor for chemical analysis of the reactor effluent.

50mg of the Fe-MFAM was placed between quartz wool plugs in a 0.3 cm i.d. fused silica reactor in the STDS. All transfer lines were maintained at a constant temperature of 180°C. Prior to each flow reactor experiment, Fe-MFAM was activated in situ at 450 °C for 1 hr at an air flow rate of 5 cc/min. The 2-MCP (Aldrich, 99.9% pure) was introduced into a nitrogen stream by a syringe pump through a vaporizer maintained at 180 °C. The rate of injection was selected to maintain a constant concentration of 50 ppm of 2-MCP for temperatures ranging from 200 to 550°C, and a constant contact time with the catalytic bed of 0.02s. Total reaction time was maintained at 1 hour.

The products from the reaction were analyzed using an in-line Agilent 6890 GC-MSD system. For product separation, a 30 m, 0.25 m i.d., 0.25 micron film thickness column was used (Restek RTS 5MX) with a temperature hold at -60 °C for the reaction period followed by a temperature programmed ramp from -60 to 300 at 10 °C/min. Detection and quantification of the products were obtained on an Agilent 5973 mass spectrometer, which was operated in the full-scan mode from 15-350 amu for the duration of the GC run. The yields of the products were calculated by use of the expression:

where; [PROD] is the concentration of specific product formed (in moles); [2-MCP]0 is the initial concentration of 2-MCP (in moles); A is the molar stoichiometric factor.

Quantitative standards were used to calibrate the MS response for all products.

2. RESULTS

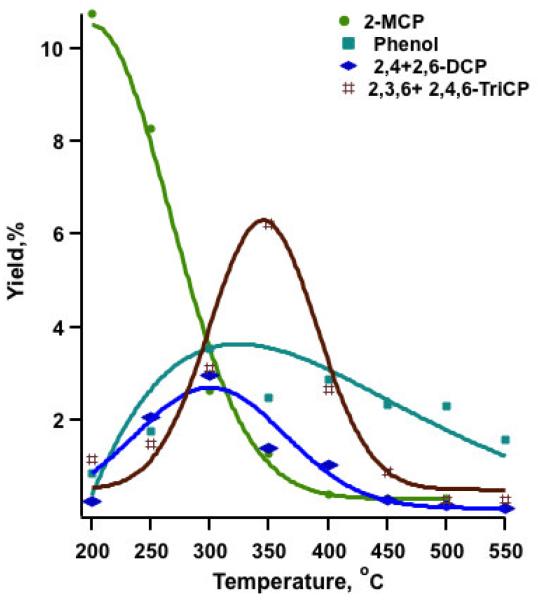

Significant catalytic degradation of the reactant occurred by 200 °C, with only about 11% of the initial 2-MCP remaining undestroyed. Rapid and accelerated conversion was observed at above 300°C, achieving almost complete degradation of 2-MCP by 400°C (cf. Figure 1, SI-Table 1). Chlorophenols (CPs) and chlorobenzenes (CBzs) were the major aromatic products, with chlorophenols observed in greater yields than chlorobenzenes (cf. Figure 1, Figure 2, SI-Table 1).

Figure 1.

Yields of chlorophenols from the oxidation of 2-MCP over an Fe2O3/silica surface.

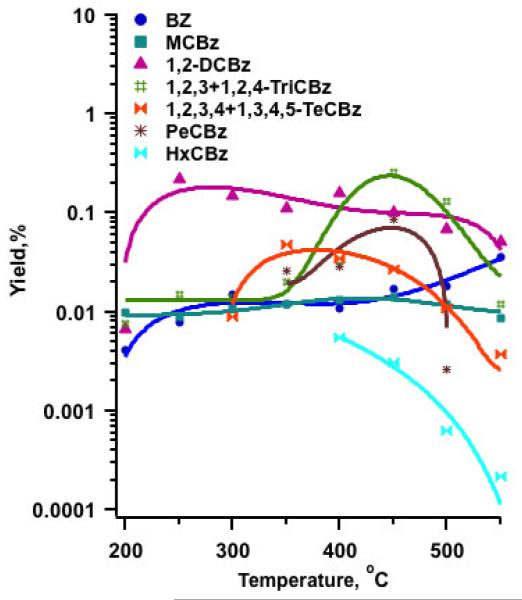

Figure 2.

Yields of chlorobenzenes from the oxidation of 2-MCP over an Fe2O3/silica surface

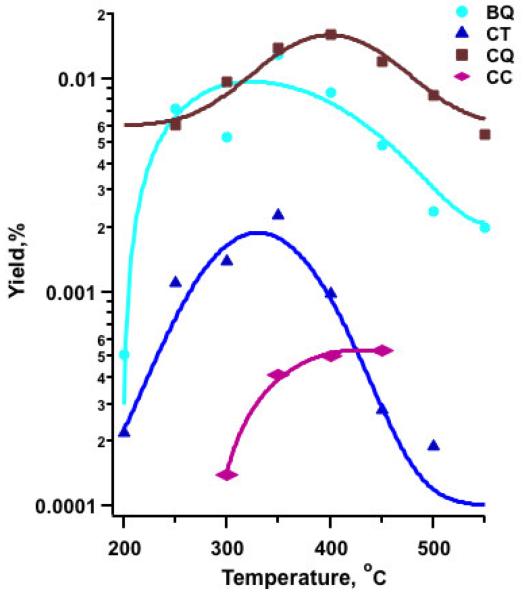

Benzoquinone (BQ), catechol (CT), 3-chloro-o-quinone (CQ) and 3-chlorocatechol (CC), important surface intermediates of PCDD/F formation, were also observed (cf. Figure 3, SI-Table1). Other non-dioxin products included chloronaphthalene, naphthalene, and biphenyl.

Figure 3.

Yields of o-quinones, benzoquinone (BQ) and chlorobenzoquinone (CQ), and catechols, catechol (CT) and chlorocatechol (CC) over an Fe2O3/silica surface.

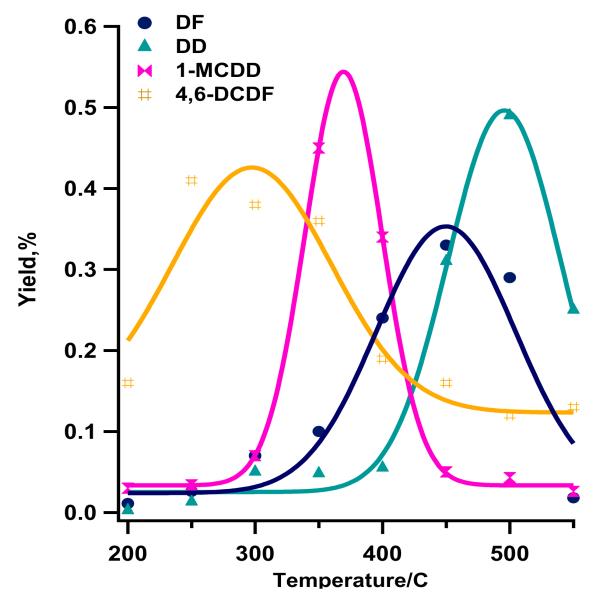

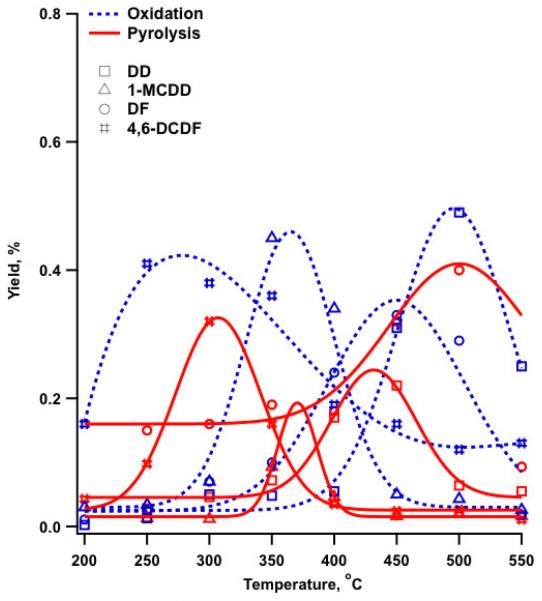

The observed dioxin products were: dibenzo-p-dioxin (DD), 1-monochlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (1-MCDD), 4,6-dichlorodibenzofuran (4,6-DCDF), and dibenzofuran (DF). The maximum yields of 4,6-DCDF and 1-MCDD were at 250 and 350°C, respectively, whereas DD and DF exhibited maximum yields at 500°C and 450°C, respectively (cf. Figure 4, SI-Table1).

Figure 4.

Yields of dibenzo-p-dioxin, (DD), 1-monochloro dibenzo-p-dioxin (1-MCDD), dibenzofuran (DF) and 4,6-dichlorodibenzo-furan (4,6-DCDF) from oxidation of 2-MCP over Fe2O3/silica:

As anticipated, there were only relatively small differences observed between oxidation and pyrolysis of 2-MCP over iron oxide. Below 300 °C, the oxidative and pyrolytic degradation of 2-MCP were comparable (~90%). At 300 °C, the oxidative degradation increased, with 2-MCP reduced to ~2% of its initial concentration under oxidative conditions versus ~9% under pyrolytic conditions (Nganai et al., 2009). These data indicate a Mars-van Kreevelen mechanism for Fe2O3, similar to that previously proposed for CuO assisted oxidation of 2-MCP, where surface oxygen is primarily involved in the oxidation process(Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003a).

The formation of chlorophenols and chlorobenzenes at moderate temperatures (below 500 °C) suggests adsorption of 2-MCP on the Fe2O3/silica surface, followed by chlorination. The observed hydroxylated reaction intermediates, such as catechol (B enzene-1,2-diol), benzoquinone (1,4-cyclohexadiene-5,6-dione), 3-chlorocatechol (3-chlorobenzene-1,2-diol) and 3-chlorobenzoquinone (1,4-cyclohexadiene-4-chloro-5,6-dione) indicates the involvement of surface-associated semiquinone-type radicals (Lomnicki et al., 2008).

3. DISCUSSION

3.1 Adsorption and Reactions of 2-MCP on a Fe2O3/Silica surface

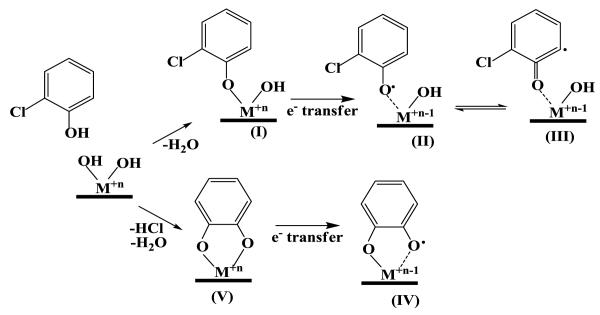

We have previously demonstrated that 2-MCP interacts with the surfaces of metal oxides through a chemisorption mechanism (Farquar et al., 2003; Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003a; Vejerano et al., 2011). Two pathways of chemisorption have been proposed for chlorophenols: i) elimination of H2O (upper path in Scheme 1) and ii) elimination of both H2O and HCl (lower path Scheme 1) (Lomnicki et al., 2008; Nganai et al., 2009). We have previously shown iron oxide and copper oxide exhibit similar behavior (Nganai et al., 2009). Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and X-Ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) studies, where 2-MCP is adsorbed to a copper oxide surface, indicates that once 2-MCP is chemisorbed to Cu(II)O surface, an electron transfer process occurs from 2-MCP to Cu(II), which reduces to Cu(I), forming surface-associated, persistent free radicals such as chlorophenoxy radicals, species II and III and semiquinone-type radicals, species V (Dellinger et al., 2007). Some of these radicals are resonance stabilized and can exist as primarily oxygen-centered or carbon-centered mesomers (cf. Scheme 1 Species II and III) (Farquar et al., 2003).

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of adsorption of 2-MCP on an Fe2O3/silica.

Once chemisorbed to the surface, the adsorbed species can undergo multiple transformations that include oxidation/decomposition, condensation, chlorination or dechlorination. In the case of 2-MCP and iron oxide, a chlorination process seems to be an important pathway and significant yields of polychlorophenols were observed at temperatures as low as 250 °C. Surface hypochlorites have been suggested to act as chlorinating agents through Mars van Krevelen reactions (Bandara et al., 2001; Farquar et al., 2003; Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003a). Experimental data have shown this to occur quite easily for iron oxide (Vejerano et al., 2011). The formation of the surface hypochlorite species involves bond formation between surface oxygen and chlorine, and the reaction should be sensitive to the concentration of surface oxygen. Indeed, the change in the reaction conditions from pyrolytic (Nganai et al., 2009) to oxygen rich resulted in a 6x increase in the yield of chlorophenols. Interestingly, 2,3,6-, and 2,4,6-TriCP achieved a maximum yield at 350 °C, whereas, under pyrolytic conditions, the maximum yield was observed at 250 °C.

The addition of oxygen only slightly increases the yield of chlorobenzenes. Chlorobenzenes have been proposed to form under pyrolytic conditions by ipso-attack by H at the aromatic carbon-oxygen bond and displacement of the hydroxyl group (Evans and Dellinger, 2005b). The addition of oxygen decreases H, which results in tautomerization being much faster than ipso attack under oxidative conditions (Evans and Dellinger, 2006). The slight increase in formation of chlorobenzenes is probably due to displacement by Cl., rather than H..

Formation of unchlorinated phenol and benzene under oxidative conditions achieved maxima yields 3x greater and 4x less, respectively, than under pyrolytic conditions. The reactions leading to formation of both phenol and benzene proceed by elimination of HCl (the lower path of Scheme 1). The higher yield of phenol suggests the cleavage of the metal-oxygen bond is favored over the scission of the carbon-oxygen bond, the latter forming benzene. Formation in trace amounts of BQ, CQ, CT and CC, which were below the detection limit under pyrolytic conditions, can be attributed to replenishment of terminal oxygen groups under oxidative conditions. We have previously proposed that these products are formed over a Cu(II)O surface by a mechanism involving reaction of adsorbed ortho-carbon-centered chlorophenoxyl radical species with a terminal oxygen, followed by scavenging of hydrogen by OH, and desorption of CC from the surface, which also results in reduction of the metal oxide (Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003a; Evans and Dellinger, 2005b). It is likely that similar reaction patterns and mechanisms are responsible for the formation of these products from 2-MCP chemisorbed on iron oxide surface. The increased yield under oxidative is at least partially attributed to the increased scavenging of H by more abundant OH.

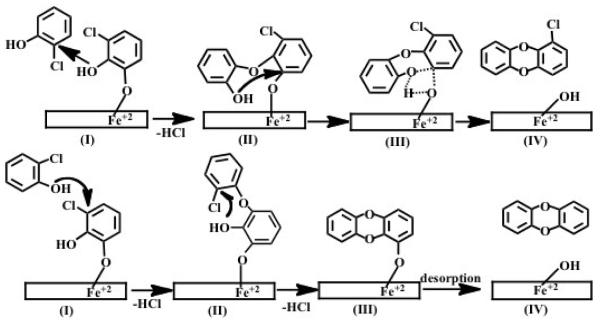

3.2 Surface Mediated Formation of PCDDs

Surface-catalyzed formation of PCDD/Fs primarily occurs through two general schemes, Langmuir-Hinshelwood and Eley-Rideal mechanisms. We have previously proposed PCDDs form from 2-MCP and 2-monobromophenol (2-MBP) over a CuO/silica surface via an Eley-Rideal mechanism, in which the reaction occurs between an adsorbed species and a gas phase species, while formation of PCDFs occurs by a Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism, which involves reaction of two adsorbed species (Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003c, a; Evans and Dellinger, 2005b, 2006). In our recent manuscript on reaction of 2-MCP over an Fe2O3/silica surface under pyrolytic conditions, we reported an additional mechanism of PCDFs formation via the bidentate intermediate (VI) depicted in Scheme 1. This species converts to the more stable keto mesomer, with further reacts to form DF. However, with addition of oxygen, the yield of DF was reduced by a factor of 3 compared to pyrolytic conditions, whereas the yields of 1-MCDD and DD increased by factors of 2 and 5 under oxidative conditions (cf. Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of PCDD/F yields from pyrolysis and oxidation of 2-MCP over Fe2O3/silica surface.

This observation suggests addition of oxygen supports a competitive reaction in which chlorophenoxyl radical tautomerizes to surface species I, depicted in Scheme 2, followed by further reactions resulting in the increased yields of PCDDs observed under oxidative conditions. This is consistent with the appearance of catechols and quinones as common precursors to 1-MCDD and DD under oxidative conditions. The yield of 1-MCDD, which increased remarkably, can be attributed to the increase in reoxidation of surface sites favorable for the two likely Eley-Rideal pathways: (i) reactions of adsorbed chlorophenoxyl radical with a terminal oxygen to form CC and CQ. In fact, a maximum yield of CC and CQ at 350-400°C coincides with the onset of PCDD formation under oxidative conditions, (ii) species I in Scheme 2 reacts either at the hydroxyl substituted site or chlorine substituted site to form surface intermediate II (both upper and lower pathways in Figure 2) via elimination of HCl. Ring closure via a cyclic transition intermediate III in the upper pathway allows for 1-MCDD to be desorbed from the surface. In contrast, 4,6-DCDF is formed via a Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism (not shown) involving surface adsorbed chlorophenoxyl radical. No significant shift in the temperature window of formation was observed for PCDDs or PCDFs under oxidative conditions. However, the additional pathways in Scheme 2 result in a 150% increase in PCDD yields under oxidative conditions versus only a 30% increase in PCDF yields (Nganai et al., 2009).

Scheme 2.

Proposed Eley-Rideal mechanism for 1-MCDD and DD formation

The PCDD:PCDF ratio was 0.75 under oxidative conditions and only 0.39 under pyrolytic conditions. This observation implies that in presence of oxygen, adsorption sites on iron oxide surfaces can easily be regenerated, and the E-R pathway of PCDD formation was faster than the L-H pathway of PCDF formation. Importantly, since the lower PCDD:PCDF ratio under pyrolytic conditions is in closer agreement with the low ratios observed in field studies, pyrolysis may be the major source of PCDD/F emissions. This suggests pockets of poor mixing and pyrolysis occurs, even under overall oxidative conditions.

3.3 Copper versus Iron Mediated Formation of PCDD/Fs

An overall comparison of our studies of 2-MCP over copper oxides and iron oxides under identical conditions indicates iron may play a more significant role in PCDD/F formation than copper. The total yields of PCDD/Fs observed under oxidative conditions were 3x higher for iron oxide than for copper oxide. Considering the fact that iron is almost always the most dominant metal in combustion exhaust, more attention and further research is needed to elucidate the role of iron in surface catalyzed formation of PCDD/Fs during combustion.

There are also mechanistic differences between copper and iron oxides as promoters of PCDD/F formation. For oxidation 2-MCP over a CuO/silica surface, the observed yield of 1-MCDD was 6x higher under oxidative conditions than pyrolytic conditions. Conversely, the yield of DD was reduced under oxidative conditions by a factor of 2 (Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003a). This difference was attributed to the differences in the ring-closing step in Scheme 2 resulting in a surface bound DD. In contrast with iron oxide, the yields of both DD and 1-MCDD increased significantly under oxidative conditions. This is directly attributable to the increased concentration of the surface species that are precursors of PCDDs under oxidative conditions over iron oxide.

Low yields of benzoquinone, 3-chloro-o-quinone, catechol and 3-chlorocatechol products were observed under both pyrolytic and oxidative conditions over CuO/silica surface,. In comparison, only trace quantities of these products were observed in oxidation of 2-MCP over Fe2O3/silica surface and were below detection limit under pyrolytic conditions. This is likely due to the oxidative properties of iron, which resulted in surface oxygen depletion under pyrolytic condition, reducing formation of I in Scheme 2. Addition of oxygen constantly replenishes the surface oxygen concentration, thus increasing the concentration of CC precursors. A correlation between the CC and DD concentrations was observed similar to that previously observed in our studies of 2-MCP over CuO/silica (Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003c, a).

The observed formation of DF from oxidation of 2-MCP over iron oxide, which was not detected for copper oxide under identical conditions, further underscores the differences in the chemisorption mechanisms over copper and iron oxides. For pyrolysis of 2-MCP over iron oxide, we previously proposed DF is formed from involving phenoxyl radical at temperatures above 350 °C (Nganai et al., 2009). reactions The higher formation temperature of DF, compared to 4, 6 - DCDF, results from the fact that henoxyl radicals are formed from the bidentate binding represented in the lower pathway in Scheme 1. Additional reaction steps are required, including C-O bond scission, to from DF, which is completed at a higher temperature. In the case of copper oxide, DF was not detected (Lomnicki and Dellinger, 2003a). Thus the upper pathway in Scheme 1, where chlorophenoxyl radical is formed, is the dominant route and forms primarily 4,6-DCDF.

These simple differences in mechanism translates into a product difference in combustion sources: copper oxide will form ClxDF from a specific precursor, while iron oxide will form a ClxDF and Clx-2DF mixture, with a prevalence of the lower chlorinated congener. Thus it might be possible to identify the metal oxides responsible for PCDD/Fs in combustion sources by following differences in chlorination levels of PCDFs

4. CONCLUSIONS

Iron oxides have been shown to effectively catalyze the formation of PCDD/Fs from the 2-Chlorophenol precursors. Comparison, between the pyrolytic and oxidative conditions of the reaction indicates, that in the former more PCDDs are formed, however, a PCDD:PCDF ratio is < 1. This is in contrast to research reported by many for copper oxide catalyzed processes, where PCDD:PCDF ratio was usually > 1. This observation is important in respect of field emission studies reporting the PCDD:PCDF ratios as <<1. One of the key differences between the copper and iron oxides is the additional dechlorination step of the precursor resulting in lower chlorinated PCDFs. from the same precursor. Studies of the PCDD/F formation over iron oxide from other precursor, such as chlorinated benzenes are desired (under way in our laboratory) to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the differences between the iron and copper oxide PCDD/F formation propensities

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Studies of the contribution of iron oxide to the formation of PCDD/Ds in the post combustion cool zone.

Effect of oxygen on the ratio of formed PCDD to PCDF.

Comparison of the PCDD and PCDF yields from the processes catalyzed by copper oxide and iron oxide.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences through Grant RO1 ES015450-01, and P42 ES013648 and the Patrick F. Taylor Chair held by B.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Database of Sources of Environmental Releases of Dioxin-like Compounds in the United State. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2001. EPA/600/C-01/012. [Google Scholar]

- Altwicker ER. Some Laboratory Experimental-Designs for Obtaining Dynamic Property Data on Dioxins. Sci Total Environ. 1991;104:47–72. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altwicker ER, Schonberg JS, Konduri RKNV, Milligan MS. Polychlorinated Dioxin Furan Formation in Incinerators. Hazard Waste Hazard. 1990;7:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ballschmiter K, Braunmiller I, Niemczyk R, Swerev M. Reaction Pathways for the Formation of Polychloro-Dibenzodioxins (Pcdd) and Polychloro-Dibenzofurans (Pcdf) in Combustion Processes .2. Chlorobenzenes and Chlorophenols as Precursors in the Formation of Polychloro-Dibenzodioxins and Polychloro-Dibenzofurans in Flame Chemistry. Chemosphere. 1988;17:995–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Bandara J, Mielczarski JA, Kiwi J. I. Adsorption mechanism of chlorophenols on iron oxides, titanium oxide and aluminum oxide as detected by infrared spectroscopy. Applied Catalysis B-Environmental. 2001;34:307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Born JGP, Louw R, Mulder P. Formation of Dibenzodioxins and Dibenzofurans in Homogenous Gas-Phase Reactions of Phenols. Chemosphere. 1989;19:401–406. [Google Scholar]

- Brzuzy LP, Hites RA. Global mass balance for polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans - Response. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:3647–3648. doi: 10.1021/es00008a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser HR. Formation of Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans (Pcdfs) and Dibenzo-Para-Dioxins (Pcdds) from the Pyrolysis of Chlorobenzenes. Chemosphere. 1979;8:415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Yeh JW, Chein HM, Hsu LY, Chi KH, Chang MB. PCDD/F adsorption and destruction in the flue gas streams of MWI and MSP via Cu and Fe catalysts supported on carbon. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:5727–5733. doi: 10.1021/es800250c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger B, Loninicki S, Khachatryan L, Maskos Z, Hall RW, Adounkpe J, McFerrin C, Truong H. Formation and stabilization of persistent free radicals. P Combust Inst. 2007;31:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.proci.2006.07.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson LC, Karasek FW. Mechanism of Formation of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-Para-Dioxins Produced on Municipal Incinerator Fly-Ash from Reactions of Chlorinated Phenols. J Chromatogr. 1987;389:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)94417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson LC, Lenoir D, Hutzinger O. Surface-Catalyzed Formation of Chlorinated Dibenzodioxins and Dibenzofurans during Incineration. Chemosphere. 1989;19:277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Evans CS, Dellinger B. Mechanisms of dioxin formation from the high-temperature oxidation of 2-chlorophenol. Environ Sci Technol. 2005a;39:122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CS, Dellinger B. Surface-mediated formation of polybrominated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans from the high-temperature pyrolysis of 2-bromophenol on a CuO/silica surface. Environ Sci Technol. 2005b;39:4857–4863. doi: 10.1021/es048057z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CS, Dellinger B. Surface-mediated formation of PBDD/Fs from the high-temperature oxidation of 2-bromophenol on a CuO/silica surface. Chemosphere. 2006;63:1291–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquar GR, Alderman SL, Poliakoff ED, Dellinger B. X-ray spectroscopic studies of the high temperature reduction of Cu(II)0 by 2-chlorophenol on a simulated fly ash surface. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:931–935. doi: 10.1021/es020838h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler H. Thermal formation of PCDD/PCDF: A survey. Environ Eng Sci. 1998;15:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorishi SB, Altwicker ER. Formation of Polychlorinated Dioxins, Furans, Benzenes and Phenols in the Postcombustion Region of a Heterogeneous Combustor - Effect of Bed Material and Postcombustion Temperature. Environ Sci Technol. 1995;29:1156–1162. doi: 10.1021/es00005a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullett BK, Bruce KR, Beach LO. The Effect of Metal-Catalysts on the Formation of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-Para-Dioxin and Polychlorinated Dibenzofuran Precursors. Chemosphere. 1990;20:1945–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Buekens A. On the Mechanisms of Dioxin Formation in Combustion Processes. Chemosphere. 1995;31:4099–4117. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Buekens A. De novo synthesis of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans - Proposal of a mechanistic scheme. Sci Total Environ. 1996;193:121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek FW, Dickson LC. Model Studies of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-Para-Dioxin Formation during Municipal Refuse Incineration. Science. 1987;237:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.3616606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai EK, T., Nakamura T, Shibata E. PCDD/Fs formation from mono-chlorobenzene on some metallic oxides. Organohalogen Compounds. 2000;46:142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kasai EK, T., Nakamura T. Formation of PCDD/Fs on iron oxides from chlorobenzene and chlorophenol. Organohalogen Compounds. 1999;41:187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier WSVA, T.R., Kilgroe JD. Assessment of trace organic emissions test results from the Montgometry Country South MWC in Dayton, Ohio. Energy Environ. Anal. Inc.; Durham, NC, USA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lomnicki S, Dellinger B. A detailed mechanism of the surface-mediated formation of PCDD/F from the oxidation of 2-chlorophenol on a CuO/silica surface. J Phys Chem A. 2003a;107:4387–4395. [Google Scholar]

- Lomnicki S, Dellinger B. Development of supported iron oxide catalyst for destruction of PCDD/F. Environ Sci Technol. 2003b;37:4254–4260. doi: 10.1021/es026363b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomnicki S, Dellinger B. Formation of PCDD/F from the pyrolysis of 2-chlorophenol on the surface of dispersed copper oxide particles. P Combust Inst. 2003c;29:2463–2468. [Google Scholar]

- Lomnicki S, Truong H, Vejerano E, Dellinger B. Copper oxide-based model of persistent free radical formation on combustion-derived particulate matter. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:4982–4988. doi: 10.1021/es071708h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland JA, Akki U, Yang Y, Ryu JY. Temperature dependence of DCDD/F isomer distributions from chlorophenol precursors. Chemosphere. 2001;42:719–727. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(00)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakka HF, A., Sidhu S. Surface catalyzed chlorobenzene transformation reactions in post-combustion zone. Organohalogen Compounds. 2004;66:1124–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Nganai S, Lomnicki S, Dellinger B. Ferric Oxide Mediated Formation of PCDD/Fs from 2-Monochlorophenol. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:368–373. doi: 10.1021/es8022495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olie K, Addink R, Schoonenboom M. Metals as catalysts during the formation and decomposition of chlorinated dioxins and furans in incineration processes. J Air Waste Manage. 1998;48:101–105. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1998.10463656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubey WA, Grant RA. DESIGN ASPECTS OF A MODULAR INSTRUMENTATION SYSTEM FOR THERMAL DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES. Review of Scientific Instruments. 1988;59:265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SP, Altwicker ER. Understanding the role of iron chlorides in the de novo synthesis of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins/dibenzofurans. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:1708–1717. doi: 10.1021/es034561c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaub WM, Tsang W. Dioxin Formation in Incinerators. Environ Sci Technol. 1983;17:721–730. doi: 10.1021/es00118a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu SS, Maqsud L, Dellinger B, Mascolo G. The Homogeneous, Gas-Phase Formation of Chlorinated and Brominated Dibenzo-P-Dioxin from 2,4,6-Trichlorophenols and 2,4,6-Tribromophenols. Combust Flame. 1995;100:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stieglitz L. Selected topics on the de novo synthesis of PCDD/PCDF on fly ash. Environ Eng Sci. 1998;15:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas VM, Spiro TG. The US dioxin inventory: Are there missing sources? Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:A82–A85. doi: 10.1021/es962098g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vejerano E, Lomnicki S, Dellinger B. Formation and Stabilization of Combustion-Generated Environmentally Persistent Free Radicals on an Fe(III)(2)O-3/Silica Surface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:589–594. doi: 10.1021/es102841s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HC, Chang SH, Hung PC, Hwang JF, Chang MB. Catalytic oxidation of gaseous PCDD/Fs with ozone over iron oxide catalysts. Chemosphere. 2008;71:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber R, Nagai K, Nishino J, Shiraishi H, Ishida M, Takasuga T, Konndo K, Hiraoka M. Effects of selected metal oxides on the dechlorination and destruction of PCDD and PCDF. Chemosphere. 2002;46:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, J. A, Akki U. Formation of furans by gas-phase reactions of chlorophenols. Symposium (International) on Combustion, [Proceedings].1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.