Abstract

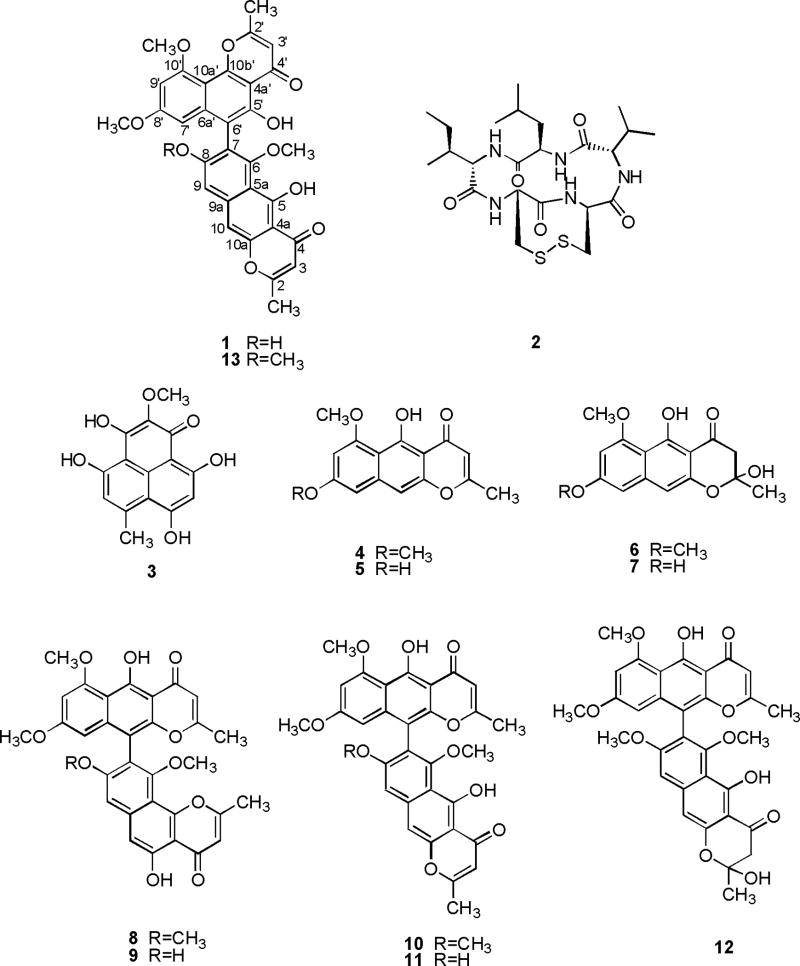

Bioactivity-guided fractionation of a cytotoxic extract of Aspergillus tubingensis, a fungal strain occurring in the rhizosphere of the Sonoran desert plant, Fallugia paradoxa, afforded a new dimeric naphtho-γ-pyrone asperpyrone D, nine known naphtho-γ-pyrones, funalenone, and the cytotoxic cyclic penta-peptide, malformin A1.

Keywords: Aspergillus tubingensis, Rhizosphere fungus, Fallugia paradoxa, Secondary metabolites, Asperpyrone D, Naphthopyrones, Malformin A1, Cytotoxic activity

1. Introduction

Plant-associated microorganisms are known to produce a variety of metabolites with novel structures and interesting biological activities (Tan and Zou, 2001; Schulz et al., 2002; Strobel et al., 2004; Gunatilaka, 2006) and the claimed medicinal properties and biological activities of some plant species have been attributed to the microorganisms living in association with these plants (Kettering et al., 2004; Chomcheon et al., 2005). As part of our ongoing efforts to understand plant-microbial interactions and to discover small molecule natural products with novel structures and/or biological activities from plant-associated microorganisms of the Sonoran desert (Turbyville et al., 2006; Wijeratne et al., 2006), we have investigated the fungal strain Aspergillus tubingensis (Trichocomaceae) occurring in the rhizosphere of Fallugia paradoxa (Apache plume; Rosaceae). An EtOAc extract of A. tubingensis was found to exhibit strong cytotoxic activity against several cancer cell lines. Bioassay-guided fractionation of this extract resulted in the isolation of a new dimeric naphtho-γ-pyrone named asperpyrone D (1), a strongly cytotoxic cyclic peptide, malformin A1 (2), funalenone (3) and nine known naphtho-γ-pyrones (4–12). A previous investigation of the sclerotia of A. tubingensis (NRRL 4700) has afforded three new aflavinines, one of which has shown insecticidal activity (TePaske et al., 1989). Monomeric and dimeric naphtho-γ-pyrones with a broad range of biological activities have been found to occur in higher plants belonging to the genera Cassia (Li et al., 2001), Paepalanthus (Coelho et al., 2000), and Senna (Barbosa et al., 2004), and in filamentous fungal genera, Aspergillus (Galmarini and Stodola, 1965; Wang and Tanaka, 1966; Sakurai et al., 2002; Akiyama et al., 2003) and Fusarium (Singh et al., 2003). Malformin A1 has previously been reported from several Aspergillus strains including A. niger (Sugawara et al., 1990), A. ficuum, A. awamori, and A. phoenicis (Iriuchijima and Curtis, 1969).

2. Results and discussion

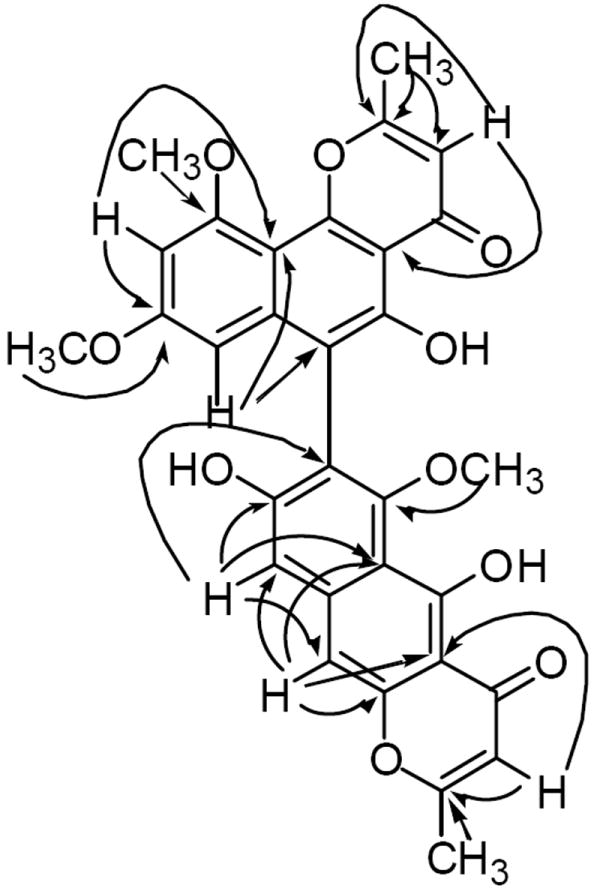

The cytotoxic EtOAc extract of A. tubingensis, collected from the rhizosphere of F. paradoxa, on fractionation using a combination of size-exclusion, normal phase, and reversed phase chromatography afforded compounds 1–12. Asperpyrone D (1) was determined to have the molecular formula C31H24O10 by HR-FAB-MS and 13C NMR spectroscopy and indicated 20 degrees of unsaturation. The bands at 3425 and 1655 cm-1 in its IR spectrum suggested the presence of hydroxyl and conjugated carbonyl functionalities. The UV spectrum of 1 showed strong absorption bands at 384, 281, 248 and 225 nm, and was found to be similar to that of asperpyrone C (13) (Akiyama et al., 2003), suggesting dimeric naphtho-γ-pyrone chromophore for 1. This was further supported by the diagnostic signals at δ 14.80 and δ 13.40 for the two phenolic hydroxyl groups in its 1H NMR spectrum (Gorst-Allman et al., 1980). The 13C NMR spectrum of 1 displayed 30 signals for 31 carbons which consisted of two methyl, three methoxy, six methine, and 20 quaternary carbons. The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 also showed two methyl singlets (δH 2.37 and 2.54), three methoxy singlets (δH 3.60, 3.62 and 3.99), six aromatic protons (two meta-coupled doublets at δH 6.27 and 6.45, and four singlets at δH 6.00, 6.33, 7.07 and 7.14), and two phenolic hydroxyls (see above). Both 1H and 13C NMR data closely resembled those of asperpyrone C (13) (Akiyama et al., 2003) except for the presence of an OH group in 1 compared with an OCH3 in 13. This OH group in 1 was located at C-8 by the HMBC correlations of H-9 with C-8 (δC 155.9). The correlations of H-7’ (δH 6.27) with C-6’ (δC 106.2), and H-9 (δH 7.14) with C-7 (δC 116.4) in the HMBC spectrum of 1 confirmed the C-7–C-6’ linkage of the two naphthopyrone moieties (Fig. 1). Thus, the structure of asperpyrone D was established as the dimeric naphtho-γ-pyrone 1 with a linear and angular monomeric moieties linked via C-7 and C-6’.

Fig. 1.

Selected HMBC correlations of 1.

The bioactive compound 2 was identified as malformin A1 (cyclo-Leu-Ile-Cys-Cys-Val) by comparison of NMR spectral data with those reported in the literature (Sugawara et al., 1990). Compounds 3–12 were characterized by comparison of their mass and NMR spectral data with those reported in the literature. Compound 3 was identified as funalenone, a rare phenalene with MMP-1 inhibitory activity previously encountered in A. niger IFO-5904 (Inokoshi et al., 1999). It is noteworthy that funalenone (3) has recently been reported to inhibit HIV-1 integrase (Shiomi et al., 2005). The remaining metabolites were identified as the monomeric naphtho-γ-pyrones, TMC-256A1 (4), rubrofusarin B (5), fonsecin B (6) and fonsecin (7), and the naphtho-γ-pyrone dimers, fonsecinone A (8), asperpyrone A (9), aurasperone A (10), dianhydro-aurasperone C (11) and aurasperone E (12).

Malformin A1 (2) has been reported to possess a variety of biological activities including plant growth stimulation (John and Curtis, 1974), prevention of interleukin-1 (IL-1) induced endothelial changes by inhibition of protein synthesis (Dawes, 1994), phytochrome-mediated response modulation of Phaseolus vulgaris (Curtis and John, 1975), as well as mycotoxic (Franck, 1984), and antibacterial activities (Suda and Curtis, 1966). In the present study malformin A1 (2) was found to be strongly cytotoxic against the human cancer cell lines NCI-H460 (non-small cell lung carcinoma), MIA Pa Ca-2 (pancreatic cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer), and SF-268 (CNS cancer; glioma) with slight selectivity towards the pancreatic cancer cell line (MIA Pa Ca-2) compared with the normal human primary fibroblast cells WI-38 (Table 1). None of the other metabolites (1 and 3 – 12) encountered in this study showed cytotoxicity towards any of the cell lines used when tested at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. However, it is noteworthy that some naphtho-γ-pyrones have been reported to reverse drug resistance in human KB cells (Ikeda et al., 1990).

Table 1.

Cytotoxic data for malformin A1 (2) against a panel of cancer cell lines and normal human primary fibroblast cellsa

| Compounds | Cell linesb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI-H460 | MIA Pa Ca-2 | MCF-7 | SF-268 | WI-38 | |

| 2 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| doxorubicin | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

Results are expressed as IC50 values in μM;

NCI-H460 = human non-small cell lung cancer; MIA Pa Ca-2 = human pancreatic cancer; MCF-7 = human breast cancer; SF-268 = human CNS cancer (glioma); WI-38 = normal human primary fibroblast cells.

3. Experimental

3.1. General

Melting points were determined on an Electrothermal micromelting point apparatus and are uncorrected. IR spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu FTIR-8300 spectrometer in KBr disks, and UV spectra in MeOH on a Shimadzu UV-1601 spectrometer. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX-500 instrument at 500 MHz for 1H NMR and 125 MHz for 13C NMR. The Chemical shift values (δ) are given in parts per million (ppm) and the coupling constants in Hz. Low-resolution APCI mass spectra were measured on a Shimadzu LCMS-8000QPα HPLC-MS system. High-resolution FAB-MS were obtained with a JEOL HX110A spectrometer.

3.2. Cytotoxicity assays

The tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay (MTT assay) (Rubinstein et al., 1990) was used for the in vitro assay of cytotoxicity to human non-small cell lung carcinoma (NCI-H460), human breast carcinoma (MCF-7), human glioma (SF-268), human pancreatic cancer (MIA Pa Ca-2) cell lines, and normal human fibroblast (WI-38) cells as previously reported (Wijeratne et al., 2003). All samples for cytotoxicity assays were dissolved in DMSO. During bioassay-guided fractionation, cytotoxicity of fractions was monitored using the NCI-H460 cell line.

3.3. Fermentation of A. tubingensis, extraction and isolation of the metabolites

A. tubingensis (Trichocomaceae) was isolated from the rhizosphere of Fallugia paradoxa (D. Don) Endl. Ponil. (Apache plume) (Rosaceae) collected in Greasewood Mountains of Tucson, Arizona. The plant identification was made by Dr. Annita Harlan and a voucher specimen was deposited at the University of Arizona Herbarium. The fungal strain was identified by Ms. Donna Bigelow by the analysis of the ITS regions of the ribosomal DNA as previously described (Wijeratne et al., 2003). The fungal strain is deposited in the Division of Plant Pathology, Department of Plant Sciences and the Southwest Center for Natural Products Research and Commercialization of the University of Arizona microbial culture collection under the accession number AH-02-35-F5. The detailed general procedures of isolation, identification and cultivation of rhizosphere fungal strains have been described previously (Wijeratne et al., 2003; Zhan et al., 2004). Methanol (200 ml) was added to each of the 44 T-flasks of a solid culture of A. tubingensis in potato dextrose agar (PDA), and the flasks were shaken overnight at room temperature, filtered, and the residue washed with MeOH (50 ml for each flask) yielding a total of 9.9 l of the MeOH extract which was concentrated to 2.4 l by evaporation under reduced pressure. The concentrated MeOH extract was extracted with EtOAc (2 l × 3). Evaporation of EtOAc under reduced pressure afforded a dark yellow solid (2.5023 g). A portion (1.9 g) of the EtOAc extract was subjected to size-exclusion chromatography on Sephadex LH-20 (60.0 g) and eluted with CH2Cl2–hexane (1:1, 500 ml), CH2Cl2–hexane (2:1, 1000 ml), CH2Cl2–hexane (4:1, 500 ml), CH2Cl2–acetone (1:1, 250 ml), acetone (250 ml), and MeOH (1000 ml). Twenty two fractions were collected and combined based on their TLC profiles to afford nine combined fractions F1–F9 [F1 (15.3 mg), F2 (79.8 mg), F3 (209.4 mg), F4 (131.0 mg), F5 (570.5 mg), F6 (129.4 mg), F7 (376.2 mg), F8 (70.5 mg) and F9 (309.2 mg)]. Of these, only F3 was found to be cytotoxic and it was separated on a column of silica gel (6.0 g) and by elution with hexane–acetone (4:1, 150 ml), hexane–acetone (3:1, 400 ml), hexane–acetone (2:1, 100 ml), hexane–acetone (1:1, 100 ml), acetone (25 ml) and MeOH (50 ml). Thirty-three fractions were collected and were combined based on their TLC profiles to yield ten sub-fractions [F3A (11.7 mg), F3B (14.5 mg), F3C (10.5 mg), F3D (10.6 mg), F3E (12.9 mg), F3F (52.7 mg), F3G (39.6 mg), F3H (13.4 mg), F3I (3.3 mg) and F3J (14.3 mg)]. Of these, sub-fractions F3H, F3I and F3J were found to be cytotoxic. These were combined and further separated by silica gel preparative TLC (developer solvent: hexane–acetone, 1:1) followed by size-exclusion chromatography on Sephadex LH-20 by elution with MeOH, yielding malformin A1 (2) (4.0 mg) as a white powder. Sub-fraction F3G was subjected to reversed phase (RP-18) preparative TLC (80% MeOH–H2O) affording 1 (0.9 mg) and 9 (4.5 mg). Compounds 6 (3.0 mg) and 7 (5.6 mg) were isolated from sub-fraction F3C using reversed phase (RP-18) preparative TLC (75% MeOH–H2O). Sub-fraction F3D was separated on silica gel preparative TLC (hexane–acetone, 3:2) followed by reversed phase (RP-18) preparative TLC (80% MeOH–H2O), yielding 8 (0.5 mg) and 10 (2.2 mg). Purification of sub-fraction F3F following a procedure identical with that used for sub-fraction F3D above, afforded 12 (4.5 mg). Compound 3 (57.3 mg) was obtained by silica gel (8.0 g) column chromatography of fraction F9 and elution with MeOH–CH2Cl2 (2:8) followed by purification by silica gel preparative TLC (MeOH–CH2Cl2, 3:7). Separation of fraction F5 on a column of silica gel (15.0 g) and elution with hexane–acetone (2:1) afforded 11 (127.6 mg) and the sub-fractions F5A (31.4 mg), F5B (33.9 mg) and F5C (168.5 mg). TLC analysis of fraction F4 and the sub-fractions F3B and F5C indicated them to be similar and therefore these were combined and subjected to silica gel preparative TLC (hexane–acetone, 3:2), yielding 4 (101.2 mg) and 5 (101.3 mg).

Asperpyrone D (1). Yellow powder, m.p. 200 °C (dec.); UV nm (MeOH) λmax (log ε): 384 (3.86), 281 (4.68), 248 (4.62), 225 (4.52); IR νmax (KBr) cm-1 : 3425, 2928, 2858, 2365, 2338, 1655, 1616, 1570, 1427, 1380, 1261, 1204, 1165 and 1065; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.80 (1H, s, OH-5), 13.40 (1H, s, OH-5’), 7.14 (1H, s, H-9), 7.07 (1H, s, H-10), 6.45 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz, H-9’), 6.33 (1H, s, H-3’), 6.27 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz, H-7’), 6.00 (1H, s, H-3), 3.99 (3H, s, OCH3-10’), 3.62 (3H, s, OCH3-6), 3.60 (3H, s, OCH3-8’), 2.54 (3H, s, CH3-2’), 2.37 (3H, s, CH3-2); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 184.5 (s, C-4), 182.7 (s, C-4’), 167.6 (s, C-2), 166.9 (s, C-2’), 162.2 (s, C-5 and C-8’), 159.5 (s, C-10’), 158.6 (s, C-6), 156.6 (s, C-5’), 155.9 (s, C-8), 155.5 (s, C-10b’), 153.1 (s, C-10a), 140.7 (s, C-6a’), 140.6 (s, C-9a), 116.4 (s, C-7), 111.5 (s, C-5a), 110.4 (d, C-3’), 108.0 (s, C-4a’), 107.2 (d, C-3), 106.2 (s, C-6’), 106.0 (d, C-9), 105.2 (s, C-10a’), 104.4 (s, C-4a), 100.9 (d, C-10), 97.4 (d, C-9’), 96.6 (d, C-7’), 62.4 (q, OCH3-6), 56.1 (q, OCH3-10’), 55.3 (q, OCH3-8’), 20.8 (q, CH3-2), 20.6 (q, CH3-2’); HR-FAB-MS: m/z 557.1431 [M+1]+ (C31H25O10 requires 557.1448).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (Grant No. 6015), National Cancer Institute (Grant No. R01CA90265), and College of Agriculture & Life Sciences of The University of Arizona for financial assistance, Dr. Hans D. VanEtten, Dr. Annita Harlan, and Ms. Donna Bigelow (all of Division of Plant Pathology, Department of Plant Sciences, The University of Arizona) respectively, for providing the fungal strain used in this study, identification of the plant species, and assistance in the identification of the fungal strain, and Ms. Manping Liu for the cytotoxicity bioassays.

Footnotes

Part 11 in the series, ‘Studies on Arid Land Plants and Microorganisms’.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akiyama K, Teraguchi S, Hamasaki Y, Mori M, Tatsumi K, Ohnishi K, Hayashi H. New dimeric naphthopyrones from Aspergillus niger. Journal of Natural Products. 2003;66:136–139. doi: 10.1021/np020174p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa FG, de Oliveira MCF, Braz-Filho R, Silveira ER. Anthraquinones and naphthopyrones from Senna rugosa. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 2004;32:363–365. [Google Scholar]

- Chomcheon P, Wiyakrutta S, Sribolmas N, Ngamrojanavanich N, Isarangkul D, Kittakoop P. 3-Nitropropionic acid (3-NPA), a potent antimycobacterial agent from endophytic fungi: Is 3-NPA in some plants produced by endophytes? Journal of Natural Products. 2005;68:1103–1105. doi: 10.1021/np050036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho RG, Vilegas W, Devienne KF, Raddi MSG. A new cytotoxic naphthopyrone dimer from Paepalanthus bromelioides. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:497–500. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis RW, John WW. Effect of malformin on phytochrome- and ethrel-mediated responses. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1975;16:719–728. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes J. Malformin A prevents IL-1 induced endothelial changes by inhibition of protein synthesis. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1994;72:482–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck B. Mycotoxins from mold fungi-weapons of uninvited fellow-boarders of man and animal: structures, biological activity, biosynthesis, and precautions. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1984;23:493–505. [Google Scholar]

- Galmarini OL, Stodola FH. Fonsecin, a pigment of an Aspergillus fonsecaeus mutant. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1965;30:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gorst-Allman CP, Steyn PS, Rabie CJ. Structural elucidation of the nigerones, four new naphthopyrones from cultures of Aspergillus niger. Journal of the Chemical Society Perkin I. 1980;11:2474–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Gunatilaka AAL. Natural products from plant-associated microorganisms: distribution, structural diversity, bioactivity and implications of their occurrence. Journal of Natural Products. 2006;69:509–526. doi: 10.1021/np058128n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S, Sugita M, Yoshimura A, Sumizawa T, Douzono H, Nagata Y, Akiyama S. Aspergillus species strain M39 produces two naphtho-γ-pyrones that reverse drug resistance in human KB cells. International Journal of Cancer. 1990;45:508–513. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokoshi J, Shiomi K, Masuma R, Tanaka H, Yamada H, Ōmura S. Funalenone, a novel collagenase inhibitor produced by Aspergillus niger. Journal of Antibiotics. 1999;52:1095–1100. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.52.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriuchijima S, Curtis RW. Malformins from Aspergilllus ficuum, A. awamori, and A. phoenicis. Phytochemistry. 1969;8:1397–1399. [Google Scholar]

- John WW, Curtis RW. Stimulation of plant growth by malformin A. Experientia. 1974;30:1392–1393. doi: 10.1007/BF01919652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettering M, Weber D, Sterner O, Ankem T. Seconday metabolites of fungi – functions and uses. BIOspectrum. 2004;10:147–147. [Google Scholar]

- Li X-C, Dunbar DC, ElSohly HN, Jacob MR, Nimrod AC, Walker LA, Clark AM. A new naphthopyrone derivative from Cassia quinquangulata and structure revision of quinquangulin and its glycosides. Journal of Natural Products. 2001;64:1153–1156. doi: 10.1021/np010173h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein LV, Shoemaker RH, Paul KD, Simon RM, Tosini S, Skehan P, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Boyd MR. Comparison of in vitro anticancer drug-screening data generated with a tetrazolium assay versus a protein assay against a diverse panel of human tumor cell lines. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1990;82:1113–1118. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M, Kohno J, Yamamoto K, Okuda T, Nishio M, Kawano K, Ohnuki T. TMC-256A1 and C1, new inhibitors of IL-4 signal transduction produced by Aspergillus niger var niger TC 1629. Journal of Antibiotics. 2002;55:685–692. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.55.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz B, Boyle C, Draeger S, Römmert AK, Krohn K. Endophytic fungi: a source of novel biologically active secondary metabolites. Mycological Research. 2002;106:996–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi K, Matsui R, Isozaki M, Chiba H, Sugai T, Yamaguchi Y, Masuma R, Tomoda H, Chiba T, Yan H, Kitamura Y, Sugiura W, Omura S, Tanaka H. Fungal phenalenones inhibit HIV-1 integrase. Journal of Antibiotics. 2005;58:65–68. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SB, Zink DL, Bills GF, Teran A, Silverman KC, Lingham RB, Felock P, Hazuda DJ. Four novel bis-(naphtho-γ-pyrones) isolated from Fusarium species as inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2003;13:713–717. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)01057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel G, Daisy B, Castillo U, Harper J. Natural products from endophytic microorganisms. Journal of Natural Products. 2004;67:257–268. doi: 10.1021/np030397v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda S, Curtis RW. Antibiotic properties of malformin. Applied Microbiology. 1966;14:475–476. doi: 10.1128/am.14.3.475-476.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara F, Kim KW, Uzawa J, Yoshida S, Takahashi N, Curtis RW. Structure of malformin A2, reinvestigation of phytotoxic metabolites produced by Aspergillus niger. Tetrahedron Letters. 1990;31:4337–4340. [Google Scholar]

- Tan RX, Zou WX. Endophytes: a rich source of functional metabolites. Natural Product Reports. 2001;18:448–459. doi: 10.1039/b100918o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TePaske MR, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF. Three new aflavinines from the sclerotia of Aspergillus tubingensis. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:4961–4968. [Google Scholar]

- Turbyville TJ, Wijeratne EMK, Liu MX, Burns AM, Seliga CJ, Luevano LA, David CL, Faeth SH, Whitesell L, Gunatilaka AAL. Studies on arid lands plants and microorganisms, Part 7. Search for hsp90 inhibitors with potential anticancer activity: isolation and SAR studies of radicicol and monocillin I from two plant-associated fungi of the Sonoran desert. Journal of Natural Products. 2006;69:178–184. doi: 10.1021/np058095b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PL, Tanaka HA. Yellow pigments of Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus awamori. II Chemical structure of aurasperone A. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1966;30:683–687. [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne EMK, Turbyville TJ, Zhang Z, Bigelow D, Pierson LS, III, VanEtten HD, Whitesell L, Canfield LM, Gunatilaka AAL. Cytotoxic constituents of Aspergillus terreus from the rhizosphere of Opuntia versicolor of the Sonoran Desert. Journal of Natural Products. 2003;66:1567–1573. doi: 10.1021/np030266u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne EMK, Paranagama PA, Gunatilaka AAL. Five new isocoumarins from Sonoran desert plant-associated fungal strains Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata and Chaetomium chiversii. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8439–8446. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan J, Wijeratne EMK, Seliga CJ, Zhang J, Pierson EE, Pierson LS, III, VanEtten HD, Gunatilaka AAL. A new anthraquinone and cytotoxic curvularins of a Penicillium sp. from the rhizosphere of Fallugia paradoxa of the Sonoran desert. Journal of Antibiotics. 2004;57:341–344. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]