Abstract

The whole plant of Stellaria media (family: Caryophyllaceae) has been tested for its antiobesity activity by using progesterone-induced obesity model in female albino mice. The effect of S. media on food consumption pattern, change in body weight, thermogenesis, lipid metabolism, and histology of fat pad. were examined. Methanolic and alcoholic extracts of the S. media were used in the study. Methanolic extract of S. media (MESM) have prevented the increase in body weight, adipose tissue weight and size, and upturned obesity and associated complications. MESM has also shown promising effects compared with alcoholic extract of S. media may be because of its multiple mechanisms. These findings suggest that antiobesity activity produced by MESM is because of its anorexic property mediated by saponin and flavonoid and partly of by its β-sitosterol content. β-Sitosterol in the plant extract was confirmed by thin-layer chromatography study. β-sitosterol is plant sterol having structural similarity with dietary fat which do the physical competition in the gastrointestinal tract and reduces fat absorption. Before carrying in vivo activity detail pharmacognostic and phytochemical analysis of the extracts was carried out. The plant has shown the presence of saponin, flavonoids, steroids and triterpenoids, glycosides, and anthocynidine. By this study, it can be concluded that, MESM is beneficial in suppression of obesity induced by progesterone.

Keywords: Anorexia, histology of fat pads, obesity, progesterone, Stellaria media, β-sitosterol

Introduction

Obesity is one of the major health concerns in the 21st century and is one of the leading causes of preventable death.[1] Among the multiple factors contributing to its etiology, the sedentary lifestyles, white collar jobs, lack of exercise, psychological factors, and the consumption of energy-rich diets are the major ones.[2,3] The medical problems caused by obesity begin at the head and end at the toes and involve almost every organ in between, and is known to be strong risk factor for type-II diabetes associated with insulin resistance. Due to incomprehensible etiology, the treatment of obesity is difficult and challenging. Furthermore, the cause of concern is the nonavailability of drugs for its treatment and the short-term efficacy and limiting side effects of the available drugs.[4]

A large study of literature indicates that substantial progress has been made concerning our knowledge of bioactive components in plant foods and their links to obesity. For the present research protocol. Stellaria media Linn (family: Caryophyllaceae) whole plant has been selected to evaluate its antiobesity and related complications. S. media is a small shrub of 20–30 cm tall found in the Dibrugarh district situated in the eastern part of Assam, India. As per the ethnobotanical claims S. media is used as astringent, carminative, antiasthmatic, demulcent, depurative, diuretic, emmenagogue, expectorant, galactogogue, useful in kidney complications, rheumatic joints, wounds, and ulcers.[5] It is also used in various kinds of skin diseases, for bronchitis, rheumatic pains and dysmenorrhoea. A poultice of chickweed can be applied to cuts, burns, and bruises.[6,7]

In the literature survey, it was found that flavonoids, sitosterols, tannins, and saponins shown promising effects to tackle obesity by various mechanisms.[8] S. media whole plant has shown the presence of sitosterols, triterpenoids, flavonoids and saponins, and others in the extracts. Moreover, traditional Indian medicine also claims for its antiobesity activity.[6] With this back ground, this plant has been selected for its phytochemical analysis and screening of its antiobesity activity against progesterone-induced obesity in female mice.

The neuroactive steroid, progesterone is a female reproductive hormone. Its level increases during the later phase of the menstrual cycle and controls the secretory phase of the endometrium. Substantial evidence links progesterone excess in pathophysiology of eating and affective disorders. Some reports suggest the use of progesterone-containing preparations as contraceptive or for the hormone replacement therapy to cause sufficient weight gain by causing hyperphagia and increased fat deposition in the body.[9] Reports also suggest that progesterone can produce these effects by inducing myriad of neurotransmitter changes of which alterations of serotonin level can have important. With this setting neuroactive to induce obesity in female mice has been chosen.

Materials and Methods

Plant authentication

Plant samples of the S. media Linn were collected in July-August 2007 from Dibrugarh district of Assam, India, and verified by Prof. (Dr.) H.B. Singh, Head, Raw Materials Herbarium and Museum, NISCAIR, New Delhi, India. Duplicate herbariums were also retained in the Department of Pharmacognosy of Shree H. N. Shukla Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Rajkot, for the future reference, the voucher No. of specimen is HNSIPER/herb/09.

Materials

Remi research centrifuge (R-24), Soxhlet extractor, OLYMPUS iNEA 5×, 10×/0.2; India, and 100X/1.25 oil, India, Shimadzu UV-visible Spectrophotometer (UV1800), microtone, Open field model was fabricated based on earlier standard literature, Stat Fax autoanalyzer (2000), Afcoset digital balance (ER-180A), etc.

Chemicals

Sibutramine was gifted by the Ranbaxy Laboratory Ltd, Devas, MP (India), and biochemical kits of Span diagnostics. All the chemicals used in the study were of analytical grade.

Animals

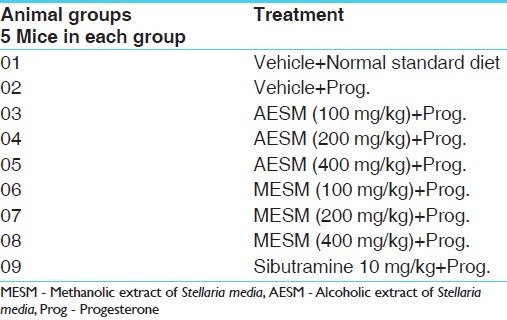

Forty five female albino mice (20–25 g) were used in this study. Mice bred at central animal house in Shree H. N. Shukla Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Rajkot, Gujarat, are used in this experiment. Animals were housed in a standard controlled animal care facility in cages (5 mice/cage). The animals were maintained in a temperature-controlled room (22°C–25°C, 45% humidity) on a 12:12 h dark:light cycle. The animals were maintained under standard nutritional and environmental conditions throughout the experiment. All the experiments were carried out between 9:00–16:00 hours at ambient temperature. Nations CPCSEA guidelines were strictly followed and all the studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC), (Ref: IAEC/HNSIPER/RJK/05/2009) Shree H. N. Shukla Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research. Rajkot, Gujarat [Table 1].

Table 1.

Treatment schedule: Number of groups with their treatment schedule

Preparation of extract

The collected plant was dried in shadow, powdered and passed through sieve #40 and used for extraction process. Successive solvent extraction was carried out; dried material is extracted with different solvents, starting from solvent of low polarity first with alcohol and then methanol. After extraction by one solvent, material is removed from thimble, dried, and recharged, extracted with solvent of successively high polarity. Successive solvent extraction was done by using alcohol and methanol as prescribed by Kokate (1994) to get alcoholic extract of S. media (AESM) and Methanolic extract of S. media (MESM).[10]

The extract was filtered and concentrated by using rotary flash vacuum evaporator (Roteva, Equitron, Mumbai). The extracts were dried in vacuum drier and stored below 10°C.

Phytochemical investigation

Phytochemical investigation was carried out as per the method prescribed by Kokate.[10]

Estimation of total flavonoid content

Flavonoid concentration was determined as per Chang et al.[11] A known volume of methanolic extract was diluted with 80% aqueous ethanol (0.9 mL). An aliquot of 0.5 mL was added to a test tube containing 0.1 mL of 10% aluminum nitrate, 0.1 mL 1 M aqueous potassium acetate, and 4.3 mL of 80% ethanol. After 40 min at room temperature the absorbance was determined at 415 nm with UV spectrophotometer. Total flavonoid content was calculated according to a standard curve established with Quercetin.

Estimation of total saponin glycosides

Total saponin content of both the extracts was obtained by the method prescribed by Rajpal (2002).[12]

The total saponin content was found to be 0.121%w/w and 0.108%w/w for methanolic and ethanolic, respectively.

TLC study of MESM

The stationary phase and mobile phase set for β-sitosterol as per the Harborne J.B.[13]

TLC for β-sitosterol

Plate dimension: 5 × 15 cm.

Stationary phase: Silica gel G for TLC.

Sample preparation: 5 mg methanolic extract was dissolved in 5 mL of acetone

Mobile phase: Various solvent systems have been tried for optimization of better resolution mainly using chloroform and ethyl acetate as the methanol extracts contain sterols, which are nonpolar to semi polar in nature.

Visualization: Spraying by 20% sulfuric acid in methanol.

Treatment after spraying: Heated in oven at 105°C for 2–5 min.

Induction of progesterone-induced obesity

Progesterone vial contents were dissolved in arachis oil and a dose of 10 mg/kg was administered subcutaneously in the dorsal neck region to mice for 28 days, control group received the vehicle. All drugs were given at a dose of 0.4 mL/100 g body weight. The test drugs were injected 30 min before progesterone administration.

Test drug preparation

Both the extracts (methanolic and alcoholic extracts) and standard sibutramine are soluble in water, so distilled water was used as media to dissolve. For progesterone, arachis oil was used as a vehicle and diluent for appropriate doses. All the drug concentrations were prepared freshly just before administration. All the test drugs, including the standard were given by oral gavages by p.o. route.

Evaluation

Assessment of food consumption behavior in mice

The food intake studies were carried out on days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28. The mice were deprived of food 1 h prior to experimentation and the test feed for the feeding experiments was standard mice chow modified for palatability by adding 10% of sucrose. On experimental days, 30 min after last drug administration, 10 g of sweetened chow was presented to groups of mice in glass petri dishes and food intake was recorded at 0.5, 1, and 2 h time intervals. Nearest to 0.1 g with correction for spillage and the amount of food consumed/20 g body weight was calculated.[14]

Body weight

The body weights of mice (g) were recorded every week for 28 days in each group just before dosing by using precision balance of 10 mg sensitivity.

Body temperature

The body temperature of mice were recorded on day 29 using rectal telethermometer, before and after drug administration at 1 and 2 h. After measuring the body weight, each animal was placed in specially designed restrainer to measure rectal temperature. A Yellow Spring Instrument telethermometer with a series 500 probe was used. The probe was lubricated using petroleum jelly prior to use and was inserted between 1.0 and 1.3 cm into the rectum and held in position for 10 s before temperature was determined. Measurements were made once for each animal and were conducted during a 2-h period 4 h before light offset.

Exploratory behavior

It was recorded on day 28 using open field behavior test apparatus and 30 min after test drug administration to treatment groups. The apparatus consists of fabricated chess board (black and white squares) and it consists of 64 squares (5 × 5 cm) with a wall of 15 cm thickness. Open field test was performed by placing the mice in the center and recording the ambulatory activity (squares crossed by horizontal movement), the frequency of rearing (standing up vertically) and grooming (face washing and repetitive licks directed to body). The mouse was placed in the center of the field and observations were recorded by Sony handy cam for 5 min. Animals were kept under laboratory condition 1 h prior to the test. Behavior was recorded by Sony handy cam for noting exact reading and storage of data. Between the trials the field was cleaned after every reading with wet sponge and tissue papers.

Biochemical parameters

Preparation of serum

On day 29 of the study, that is, after the last test drug administration, the mice were anesthetized under light ether anesthesia and blood for serum preparation was collected by retro orbital puncture, using 10 μL×20 mm (L) × 0.8 mm (2R) glass capillary into sterile EDTA-coated tube (3 mg/mL) for the estimation. Blood was kept in wet ice for 30 min, centrifuged for 5 min at 4000 rpm at 4°C (REMIMAK, Remi Instruments Ltd, Mumbai, India) and plasma was aspirated out for the analysis of lipid profile and glucose. The serum was stored in the refrigerator for the analysis of biochemical parameters. All analyses on serum were completed within 24 h of sample collection. Serum samples were analyzed for glucose, triglyceride, and total cholesterol, using biochemical kits of Span Diagnostics glucose: GOD/POD (Glucose oxidase-peroxidase) method;[15] cholesterol: One step method of Wybenga and Pilleggi;[16] triglycerides: GPO–PAP (glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase – phenol aminophenazone) end point method,[17] and HDL-C (high density lipoprotein cholesterol) by CHOD–PAP (cholesterol oxidase- phenol aminophenazone)[16] method.

Organ weights and white adipose tissue

The mice were sacrificed by spinal dislocation day 30 and then various organs, such as kidneys (right and lift kidney), liver, heart, and body fat, that is, white adipose tissue (WAT) (periovarian, perirenal, and mesenteric fat pad) were isolated, and the organ to body weight (mg/g) ratio was recorded. Adiposity index, a quantitative measure of total fat mass was also calculated using the previously determined equation.[18]

Adiposity Index (%)=[∑(fat pad)/(body weight×100)]

Isolation of fat pads

Four regions of adipose tissue were carefully dissected:

The periovarian fat, ovaries were taken out by gentle squeezing from the peripheral fat and then by horizontal cut from all sides fat was isolated; care has been taken that too much traction was avoided on ovaries and fat.

The retroperitoneal, by first separating the perirenal fat and then dissecting the retroperitoneal pad in toto.

The mesenteric, all fat found along the mesentery starting at the lesser curvature of the stomach and ending at the sigmoid colon was considered mesenteric fat; obtained by cutting the intestine below the duodenal–jejunum junction and stripping the fat by gently pulling the intestinal loops apart.

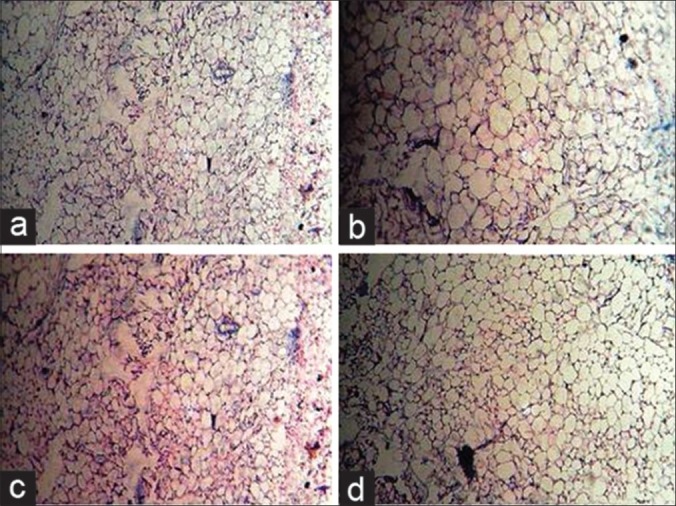

Histology of fat pad

The periovarian fat was selected for histological study. The periovarian fat of each group were excised and rinsed in 0.9% saline blotted dry of saline and excess blood. They were fixed in 12% formalin for 24 h. The tissues, after fixation, were washed in water to remove excess fixative. Washed tissues were then dehydrated through a graded series of ethyl alcohol, cleared with xylene and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections were cut at 3 μm with microtone blade and mounted on clean glass slide. The sections were routinely stained with hemotoxylin and eosin. The stained slides were observed (×200) in research microscope and photographed.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean±SEM. Comparisons between the treatment groups and positive control; positive control and control were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's test. In all the tests the criterion for statistical significance was P<0.05 (95% level). The analysis was performed by using Graph Pad Prism 4.

P value<0.05 is considered as significant (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

Observations and Results

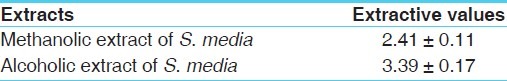

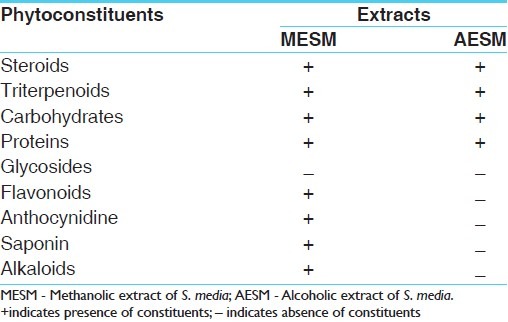

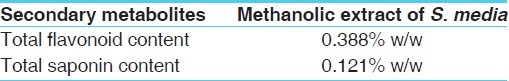

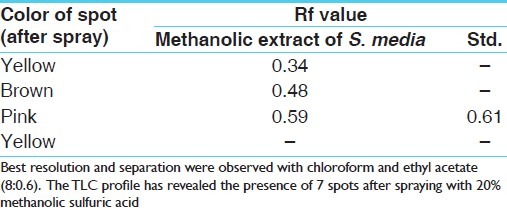

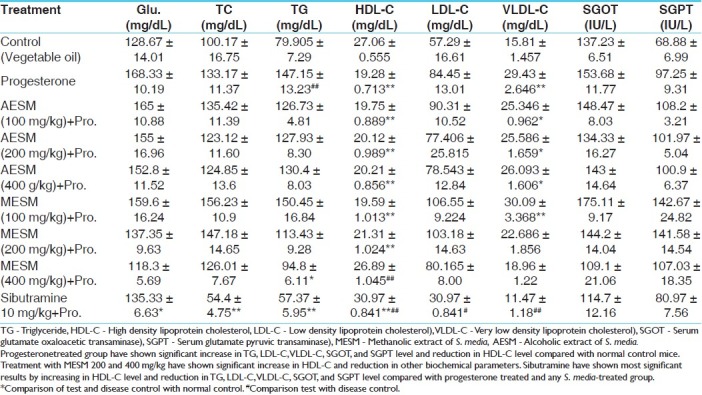

Results on extractive values [Table 2], phytochemical investigations [Table 3], estimation of total flavonoids and total saponin glycosides [Table 4], Thin Layer Chromatographic profile of MSEM for beta-sitosterol [Table 5] have been provided in respective tables. Best resolution and separation were observed with chloroform and ethyl acetate (8:0.6). TLC profile revealed the presence of 7 spots after spraying with 20% methanolic sulfuric acid. The results of effect of AESM and MESM on progesterone modulated serum bio-chemical parameters in female mice [Table 6].

Table 2.

Extractive values

Table 3.

Phytochemical investigation

Table 4.

Total flavonoids and saponin content

Table 5.

Description of TLC pattern for methanolic extract of S. media

Table 6.

Effect of AESM and MESM on progesterone modulated serum bio.chemical parameters in female mice

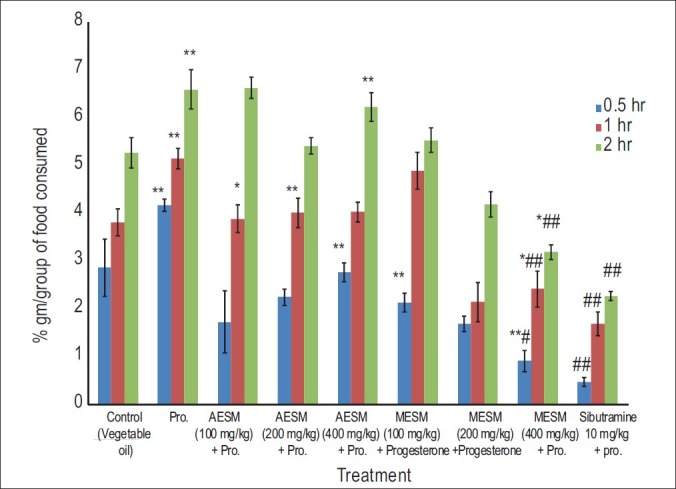

In assessment of food consumption behavior in mice, the progesterone-treated group showed significantly increased food consumption as compared with the normal control group animals at 30min, 1h, and 2h, which was decreased significantly by the co-administration of MESM 200 and 400 mg/kg compared with progesterone group and control group. Standard sibutramine was most significant in this case [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Effect of Stellaria media on Progesterone induced obesity in female mice food consumption pattern (gm / group) (*Comparison of test and disease control with normal control, #Comparison test with Disease Control)

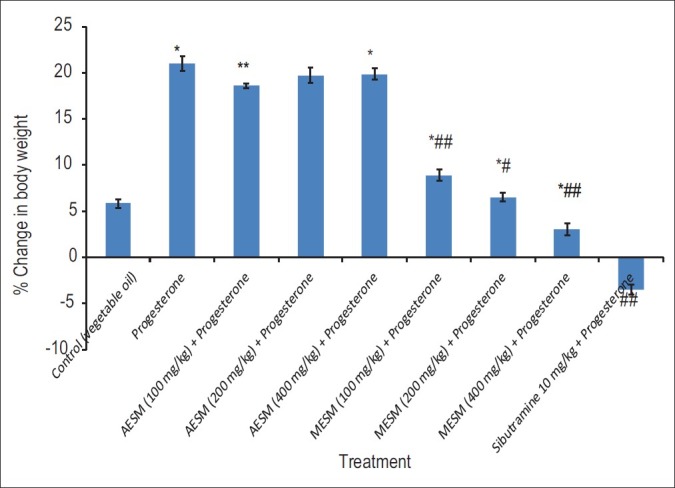

Progesterone-treated mice showed significant increase in the body weight as compared with normal control animals which was significantly decreased in MESM 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg in dose-dependent manner and most significantly by Sibutramine [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Effect of Stellaria media on Progeaterone induced obesity in female mice % change in body weight (*Comparison of test and disease control with normal control, #Comparison test with Disease Control)

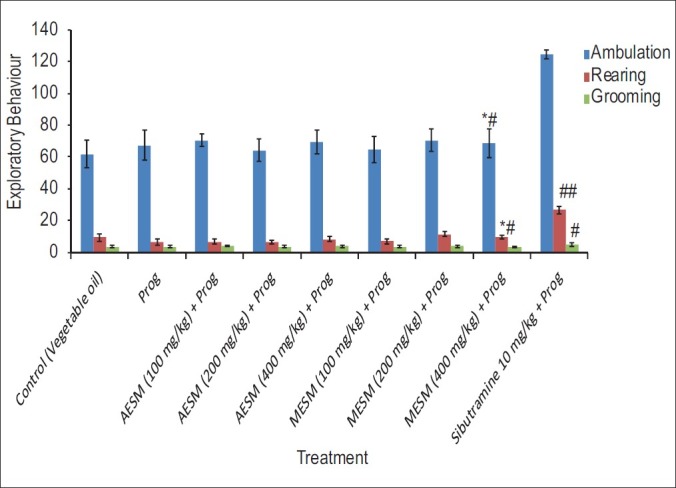

MESM 400 mg/kg has shown a significant increase in rearing and grooming behavior compared with progesterone and control groups but less than the Sibutramine treated group [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Effect of Stellaria media on Progeaterone modulated exploratory behavior in female mice (*Comparison of test and disease control with normal control, #Comparison test with Disease Control)

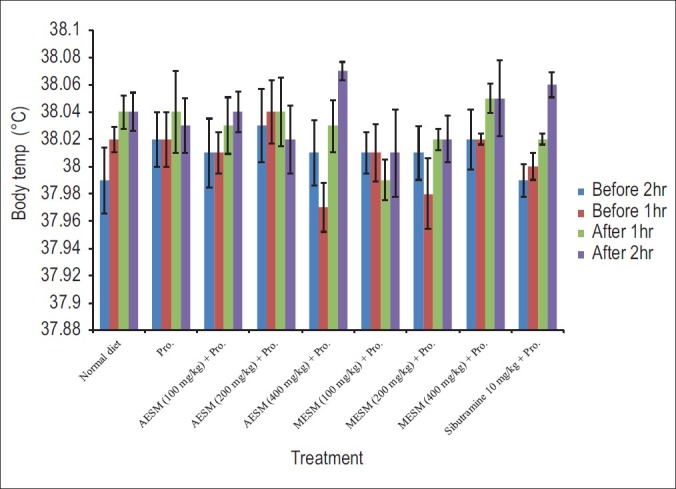

There was no significant change found in the body temperature in any of the animals [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Effect of Stellaria media on body temperature (°C) in Progesterone induced obesity in female mice for 28 days before and after drug administration. [Pro: Progesterone, AESM: Alcoholic extract of S. media. MESM: Methanolic Extract of S. media, Effect of S. media on progesterone modulated wet weight of organ/body weight ratio and WAT (mg/gm) in female mice]

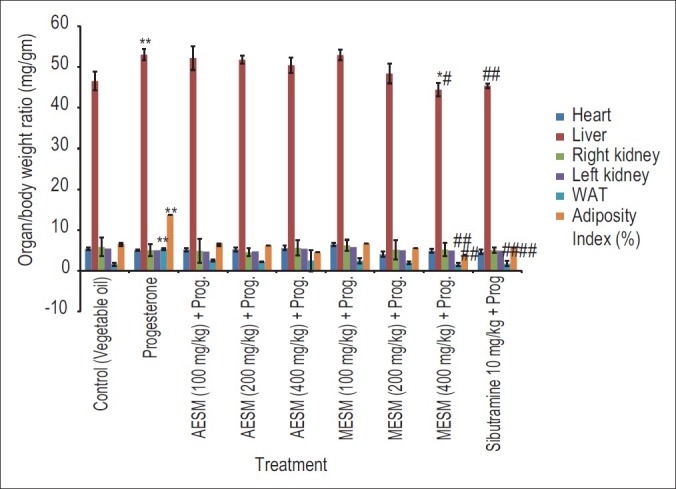

Progesterone-treated group showed significant increase in WAT, adiposity index, and liver weight compared with normal control animals, which was significantly decreased by the co-administration with MESM 200 and 400 mg/kg compared with progesterone-treated and normal control group. Sibutramine was the most significant in this regard [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Effect of Stellaria media on Progesterone modulated wet weight of organ / body weight ratio (mg / gm) in female mice (*Comparison of test and disease control with normal control, #Comparison test with Disease Control)

Light micrography of periovarian adipocytes in mice treated with progesterone (×200). Representative pictures of haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of periovarian adipocytes from mice control and progesterone induced group supplemented with extracts of S. media at various doses. Plain progesterone induced group have shown larger size of adipocytes compared to normal control diet.

Treatment with MESM (400 mg/kg), along with progesterone have shown smaller size of adipocytes than mice treated with plain progesterone [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Effect of Stellaria media on progesterone modulated histological changes of fat pad: a) Treatment with Vehicle & Normal chow diet, b) Treatment with vehicle & prog, c) Treatment with MESM (400 mg/kg) & prog, d) Treatment with Sibutramine (10 g/kg) & prog. Prog: Progesterone

Discussion

Obesity is a chronic metabolic disorder that results from the imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure characterized by enlarged fat mass and elevated lipid concentration in blood. Globally more than 1.1 billion adults worldwide are overweight and 312 million of them are clinically obese. In addition, at least 155 million children worldwide are overweight or obese, according to the National Obesity Task Force.[19]

Many attempts have been made to correct the metabolic disparity of the obesity condition, producing a number of reagents, including fibrates, sibutramine (an anorectic or appetite suppressant) and orlistat but no one is free from severe side effects.[20–22] At present, because of dissatisfaction with high costs and potentially hazardous side effects, the potential of natural products for treating obesity is under utilized, and this may be an excellent alternative strategy for developing future effective, safe antiobesity drugs. A variety of natural products, including crude extracts and isolated compounds from plants, can induce body weight reduction and prevent diet-induced obesity. Therefore, they have been widely used in treating obesity.[23,24]

A variety of natural products, including crude extracts and isolated compounds from plants, can cause body weight reduction, therefore they have been widely used in treating obesity.[23,24]

S. media, commonly known as chickweed, is found throughout the Himalayas up to an altitude of 4300 m. It is reported to be very useful in the treatment of inflammations of the digestive, renal, respiratory, and reproductive tracts. The plant is employed in plasters used for broken bones and swellings. It also possesses diuretic, expectorant, and antiasthmatic properties. Some phenolic acids, flavones, fatty esters, and gypsogenin were reported earlier from this species.[25] Traditional system of Indian medicine also reports for its antiobesity activity.[6]

The present investigation was carried out to evaluate the antiobesity activity of S. media against progesterone-induced obesity in female albino mice. The treatment and grouping is as explained in Table 1. In our study initially pharmacognostic and phytochemical analyses were carried out and in the phytochemical investigation it was clear that S. media contains triterpenoids, glycoside, carbohydrates, proteins, flavonoids, anthocynidine, and saponins. The results of extractive values and phytochemical analysis are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Some of the chemical constituents, such as saponins, flavonoids , and some triterpenoids, have been reported for their antiobesity effect in various plants.[8] Based on this phytochemical study and ethnobotanical claims this plant was selected for carrying out this study.

The neuroactive steroid progesterone is a female reproductive hormone. Its level increases during the second part of the menstrual cycle and control the secretory phase of endometrium. As the name suggesting, (Pro=for, gest=gestation), the higher endogenous levels of progesterone and its metabolites in pregnant women are reported to enhance food ingestion throughout pregnancy and conserve energy for the growing fetus. Progesterone also exerts antiestrogenic effects, which also have been shown to increase the food intake. Furthermore, some reports suggest that use of progesterone-containing preparation as contraceptive or for hormonal replacement therapy causes significant weight gain by increasing fat deposition. Furthermore, progesterone has been reported as the most fattening of steroid hormones that promotes synthesis and storage of fats. Therefore, progesterone-induced hyperphagia causes weight gain and fat deposition is useful as animal model of drug-induced obesity.[14]

The results demonstrated progesterone (10 mg/kg)-induced hyperphagia and maximum effect has been observed at 10 mg/kg dose. These results are consistent with the reported studies, that is, progesterone dose-dependent increase in food intake.[26] In the study conducted by Kaur and Kulkarni,[27] the subchronic treatment with progesterone for 4 weeks significantly increased food intake and body weight in female mice. The progesterone-induced group has showed significant increase in food consumption as compared with the normal control group animals at 30 min, 1 h, and 2 h, which was significantly decreased by the co-administration of MESM 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg compared with progesterone-treated group. [Figure 1] Standard sibutramine was most significant compared with progesterone-treated group and normal group.

It is believed that progesterone producing hyperphagia via progestin receptors, which have been reported to be expressed on the serotonergic neurons,[28] and that sibutramine suppresses the progesterone-induced hyperphagia by inhibiting reuptake of 5-HT (serotonin) at the hypothalamic site, which regulate the food intake, and this suggests the possible interaction between the neurosteroid and serotonin receptor system in regulating food intake and body weight. Furthermore, these data implicate that disturbances in the ovarian hormone levels may predispose females to eating disorders by causing alterations in the serotonin level or serotonergic receptor function.[14] The reduction in the food intake by the administration of MESM at medium and high dosages may be due to its saponin and flavonoid content; these phytoconstituents are present in abundant quantity, which is confirmed by total saponin and total flavonoid contents of the extract as given in Table 4. Crude saponin and flavonoid have been reported to have appétite suppressant property.[8] From this study we are predicting that saponin and flavonoids after absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, cross the blood–brain barrier and enter in the brain and amplify signaling in the basal hypothalamus energy sensing function, which is the master regulator of food intake and energy expenditure or it may also be possible that saponin inhibits the re-uptake of 5-HT in the hypothalamus. Some flavonoids also activate β-adrenergic receptors, which are involved in the burning of fats.[29]

Progesterone-treated group showed a significant increase in body weight compared with control group but co-administration with medium and high doses of MESM have shown significant reduction in the body weight compared with progesterone-treated group as given in Figure 2. Standard sibutramine has shown most significant results in this regard. The reduction in the body weight by MESM may be because of its anorexic property as explained above.

No significant changes have been observed in the exploratory behavior as seen in Figure 3.

The thermogenic effect of natural progesterone is well known and progesterone treatment has also been reported to increase the body temperature, so measurement of rectal temperature recording was considered one of the parameter in this study.[30] Drugs which demonstrate such changes indicating the thermogenic property of the drugs but in our study we have not observed any significant changes in change in body temperature even in the standard sibutramine as well as progesterone-treated group [Figure 4].

Progesterone is also reported to have various metabolic effects, such as raising basal insulin levels, stimulating lipoprotein lipase activity, and enhancing fat storage in the body.[14] In this study progesterone modulated various biochemical parameters in female mice. It caused significant increase in the serum glucose, TG, and VLDL-C levels and decrease in HDL-C levels as compared with the normal control animals, which were significantly reversed by co-administration of MESM 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg as well as standard sibutramine as given in Table 6.

There was significant increase in the organ/body weight ratio of liver, left kidney, and right kidney in progesterone-treated animals, which were significantly decreased by the co-administration of MESM 400 mg/kg and standard sibutramine. There was also a significant increase in the WAT and adiposity index in the progesterone-treated group compared with the normal control animals as indicated in Figure 5. These changes were significantly decreased by the administration of MESM 200 and 400 mg/kg, but no significant effects were observed for AESM. From the histologic study it is clear that adipocyte diameter is clearly reflected high in progesterone-treated group compared with normal diet-fed mice. Treatment with MESM (200 and 400 mg/kg) along with progesterone have shown smaller size of adipocytes than mice fed with progesterone alone. Standard sibutramine has shown the best protection in this regard as reflected in Figure 6.

Correction in lipid profile, decrease in adipocyte diameter and adiposity index by MESM may be because of β-sitosterol content, confirmed by TLC study [Table 5]. Stigmasterols and β-sitosterol are the plant sterols with a structure similar to that of cholesterol. Among these, β-sitosterol compound is more similar to cholesterol except for the substitution of an ethyl group at C-24 of its side chain, and it is a cholesterol-lowering agent.[31] β-sitosterol reduced absorption of cholesterol by 42% in a meal containing 500 mg of cholesterol.[32]

Moreover, saponin content of the extract may also be responsible for its antiobesity effect. Reports have shown that several saponins inhibit pancreatic lipase activity.[8] Pancreatic lipase is the most important enzyme of the human lipases for digesting fats responsible for the hydrolysis of 50%–70% of total dietary fats. Verger[33] reported that dietary fat was hydrolyzed during digestion by pancreatic lipase. The two main products formed by the hydrolysis of pancreatic lipase are fatty acids and 2-monoacylglycerols.[34] These lipolytic products are mixed with bile salts, dispersed as micelles and carried in this form to the site of fat absorption. Lipid absorption takes place in the apical part of the plasma membrane of epithelial cells or enterocytes lining the gut, so inhibition of pancreatic lipase may cause decrease in fat absorption.

Saponins, flavonoids, and β-sitosterol are the bioactive phytoconstituents in S. media, which may be responsible for its antiobesity activity by multiple mechanisms as explained above.

Conclusion

Oral administration of extracts reduced the level of circulating lipids as well as the size of adipocyte diameter, resulting in the decrease of body weights in female albino mice bearing close resemblance to human obesity. Extracts appear to show such activities by decreasing food consumption, modulating the lipid metabolism through the decreased absorption of dietary fats, and may be inhibition of pancreatic lipase activity. Among these two extracts MESM have shown promising results compared with AESM may be its multiple targets as mentioned above. From this we also proposed that use of MESM along with progesterone might be useful to attenuate side effects of progesterone.

Acknowledgment

The authors deeply thank the Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited, Devas, India, for providing pure sample of Sibutramine hydrochloride.

References

- 1.Barness LA, Opitz JM, Gilbert-Barness E. Obesity: Genetic, molecular, and environmental aspects. Am J Med Genet. 2007;143A:3016–34. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caterson ID. Obesity and its management. Australian Prescriber. 1999;22:12–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rippe JM, Crossley S, Ringer R. Obesity as a chronic disease: Modern medical and lifestyle management. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98(10 Suppl 2):S9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(98)00704-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz WM, Goodwin NJ, Yanovski SZ. Long-term pharmacotherapy in the management of obesity. JAMA. 1996;276:1907–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540230057036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard M. Few plants and animal based folk medicine, from Dibrugadh district, Assam Traditional folk remedies: A comprehensive herbal. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2005;4:81–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dilip K, Manashi D, Nazim FI. Few plants and animals based folk medicines from Dibrugarh District, Assam. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2005;4:81–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katewa SS, Chaudhary BL, Jain A. Folk herbal medicines from tribal area of Rajasthan, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;92:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun JW. Possible anti-obesity therapeutics from nature – A review. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1625–41. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amatayakul K, Sivasomboon B, Thanangkul O. A study of the mechanism of weight gain in medroxyprogesterone acetate users. Contraception. 1980;22:605–22. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(80)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokate CK. Handbook of Practical Pharmacognosy. 4th ed. Delhi: Vallabh Prakashan; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang C, Yang M, Wen H, Chern J. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J Food Drug Anal. 2002;10:178–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajpal V. “Standardization of Botanicals”. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Eastern Publishers; 2002. p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harborne JB. Methods in plant biochemistry. I. Plant phenolics. London: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 243–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur G, Kulkarni SK. Evidence for serotonergic modulation of progesterone-induced hyperphagia, depression and algesia in female mice. Brain Res. 2002;943:206–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trinder P. Determination of glucose in blood using glucose oxidase with an alternative oxygen acceptor. Assoc Clin Biochem. 1969;6:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry RJ. Clinical Chemistry. 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row Publishers; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mc Gowan FX, Reiter MJ, Pritchett EL, Shand DG. Verapamil plasma binding: Relationship to a-i-acid glycoprotein and drug efficacy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:485–90. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregoire FM, Zhang Q, Smith SJ, Tong C, Ross D, Lopez H, et al. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:E703–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00072.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Task Force of the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Weight cycling. J Ameri Med Assoc. 1994;272:1196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lean ME. How does sibutramine work? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(Suppl 4):S8–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poston WS, Foreyt JP. Sibutramine and the management of obesity. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004:633–42. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tziomalos K, Krassas GE, Tzotzas T. The use of sibutramine in the management of obesity and related disorders: An update. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:441–52. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moro CO, Basile G. Obesity and medicinal plants. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:S73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rayalam S, Della-Fera MA, Ambati S, Yang JY, Park HJ, Baile CA. Enhanced effects of 1, 25(OH) 2D3 plus genistein on adipogenesis and apoptosis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:539–46. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pande A, Shukla YN, Tripathi AK. Lipid Constituents from Stellaria media. Phytochemistry. 1995;39:709–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy DS, Kulkarni SK. The role of GABA-A and mitochondrial diazepam-binding inhibitor receptors on the effects of neurosteroids on food intake in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1998;137:391–400. doi: 10.1007/s002130050635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaur G, Kulkarni SK. Antiobesity effect of a polyherbal formulation, OB-200 g in female rats fed on cafeteria and atherogenic diets. Indian J Pharmacol. 2000;32:294–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bethea CL, Gundlah C, Mirkes SJ. Ovarian steroid action in the serotonin neuronal system of macaques, Novartis Found. Symposium. 2000;230:112–33. doi: 10.1002/0470870818.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohkoshi E, Miyazaki H, Shindo K, Watanabe H, Yoshida A, Yajima H. Constituents from the leaves of Nelumbo nucifera stimulate lipolysis in the white adipose tissue of mice. Planta Med. 2007;73:1255–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-990223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piette AM, Darai E, Gepner P, Brousse C, Chapman A. A new cause of prolonged fever of unknown origin: Progesterone substitution therapy. Presse Med. 1994;23:1699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lees AM, Mok HY, Lees RS, Mc. Cluskey MA, Grundy SM. Plant sterol as cholesterol-lowering agent: Clinical trials in patients with hypercholesterolemia and studies of sterol balance. Atherosclerosis. 1977;28:325–38. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(77)90180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattson FH, Grundy SM, Crouse JR. Optimizing the effect of plant sterols on cholesterol absorption in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;35:697–700. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/35.4.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verger R. Pancreatic lipase. In: Borgstrom B, Brockman H. L, editors. In: Lipase. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1984. pp. 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernell O, Staggers JE, Carey MC. Physical-chemical behavior of dietary and biliary lipids during intestinal digestion and absorption. 2. Phase analysis and aggregation states of luminal lipids during duodenal fat digestion in healthy adult human beings. Biochemistry. 1990;27(29):2041–56. doi: 10.1021/bi00460a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]