Abstract

Cordia dichotoma Forst.f. bark, identified as botanical source of Shlesmataka in Ayurvedic pharmacopoeias. Present study was carried out with an objective to investigate the antibacterial and antifungal potentials of Cordia dichotoma bark. Antibacterial activity of methanol and butanol extracts of the bark was carried out against two gram negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and two Gram positive bacteria (St. pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus). The antifungal activity of the extracts was carried out against three common pathogenic fungi (Aspergillus niger, A.clavatus, and Candida albicans). Zone of inhibition of extracts was compared with that of different standards like Amplicilline, Ciprofloxacin, Norfloxacin and Chloramphenicol for antibacterial activity and Nystain and Greseofulvin for antifungal activity. The extracts showed remarkable inhibition of zone of bacterial growth and fungal growth and the results obtained were comparable with that of standards drugs against the organisms tested. The activity of extracts increased linearly with increase in concentration of extract (mg/ml). The results showed the antibacterial and antifungal activity against the organisms tested.

Keywords: Antibacterial, antifungal, Cordia dichotoma, gram positive, gram negative, in vitro

Introduction

Antibiotics are one of the most important weapons in fighting bacterial infections and have greatly benefited the health related quality of human life since their introduction. However, over the past few decades, these health benefits are under threat as many commonly used antibiotics have become less effective against certain illnesses not only because many of them produce toxic reactions, but also due to emergence of drug resistant bacteria. Drugs derived from natural sources play a significant role in the prevention and treatment of human diseases. Infectious diseases are the second leading cause of death world-wide.[1] In industrialized nations, despite the progress made in the understanding of microbiology and their control, incidents of epidemics due to drug resistant microorganisms and the emergence of hitherto unknown disease–causing microbes, pose enormous public health concerns.[2] The emergence of multidrug–resistant bacteria has created a situation in which there are few or no treatment options for infections with certain microorganisms.[3] Along with bacterial infections, the fungal infections also are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality despite advances in medicine and the emergence of new antifungal agents.[4]

Although the need for new antimicrobials is increasing, development of such agents faces significant obstacles.[5] A number of factors make antimicrobial agents less economically attractive targets for development than other drug classes.[6] Pharmaceutical research and development costs which are estimated to be $400–$800 million per approved agent,[7] pose a considerable barrier to new drug development in general. Plants generally produce many secondary metabolites which constitute an important source of microbicides, pesticides, and many pharmaceutical drugs. Plant products still remain the principal source of pharmaceutical agents used in traditional medicine.[8,9] The effects of plant extracts on bacteria have been studied by a very large number of researchers in different parts of the plant.[10,11] Historically, plants have provided a good source of anti–infective agents; emetine, quinine, and berberine remain highly effective instruments in the fight against microbial infections. Phytomedicines have shown great promise in the treatment of intractable infectious diseases including opportunistic HIV infections. Plants containing protoberberines and related alkaloids, picralima–type indole alkaloids, and garciniabiflavonones used in traditional African system of medicine, have been found to be active against a wide variety of micro-organisms.[12] Many plants have been reported to have antifungal activity.[13,14]

Cordia dichotoma Linn. (Boraginaceae) is tree of tropical and subtropical regions, commonly known as Lasura in Hindi and Shlesmataka in Sanskrit. It is a medium sized tree with short crooked trunk, leaves simple, entire and slightly dentate, elliptical–lanceolate to broad ovate with round and cordate base, flower white, fruit drupe, yellowish brown, pink or nearly black when ripe with viscid sweetish transparent pulp surrounding a central stony part.[15] It grows in sub-Himalayan tract and outer ranges, ascending up to about 1500 m elevation.[16] It is used as immunomodulator, antidiabetic, anthelminitic, diuretic and hepatoprotective in folklore medicine. Seeds have disclosed the presence of α–Amyrin, betulin, octacosanol, lupeol–3–rhamnoside, β–sitosterol, β–sitosterol–3–glucoside, hentricontanol, hentricontanol, taxifolin–3,5–dirhmnoside, and hesperitin–7–rhamnoside.[17] Preliminary phytochemical analysis of C. dichotoma bark indicated the presence of relatively high levels of alkaloids, flavonoides, steroids, and terpenoids. Hence, the present investigation was undertaken to determine the antioxidant potential of C. dichotoma bark.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Cordia dichotoma bark was collected from its natural habitat, Jamnagar, Gujarat, India, in the month of April-May 2009. The plant was authenticated by the Pharmacognosy Laboratory, I.P.G.T. and R.A. Jamnagar, Gujarat, India.

Preparation of extracts

The bark was shade dried and crushed to make coarse powder. The powder (303 g) was successively extracted by soxhlet extraction with solvents of increasing polarity beginning with 2 L petroleum ether (60–80C) and then extracted with 3 L of methanol (95%v/v) by continuous extraction method for 48 h. In this methanolic extract, solvent was distilled off and the extract was concentrated and dried under reduced pressure, which yielded a brownish green mass. The extract was preserved at 2–4°C and butanol (BuOH) extracts were obtained after successive partition from methanol (MeOH) extracts. MeOH and BuOH extracts were used in this study.

Preliminary phytochemical screening of extract

The methanolic extract was analysed to detect for the presence of different chemical groups as per the methods described in Ayurvedic Pharmacopia of India. Preliminary phytochemical screening shows the presences of relatively high levels of alkaloids, coumarines, flavonoides, steroids, terpenoids, tannin, etc.

Microorganism

The microorganisms employed in the current study were procured from Microcare Laboratory, Surat (Gujarat); standard cultures of different species of two gram positive and two gram negative bacteria including pathogenic and nonpathogenic and three pathogenic fungi strains were used.

Media

Nutrient broth, nutrient agar, malt extract broth, and Sabouraud dextrose agar, from Himedia Laboratories, Mumbai (India), were used in this study.

Antimicrobial and antifungal agents

Amplicilline, Ciprofloxacin, Norfloxacin, Chloramphenicol for antibacterial activity and Nystain and Greseofulvin for antifungal activity.

Antibacterial and antifungal activity

The antibacterial activity was evaluated on four common pathogenic bacteria viz. Escherichia coli MTCC 96, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 424, Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 96, and S. pyogenes MTCC 442. The antifungal activity of the extracts was evaluated on three common pathogenic fungi viz. Aspergillus niger MTCC 282, Candida albicans MTCC 227, and A. clavatus MTCC 1323.

For evaluation of antibacterial and antifungal activities of alcohol and butanol extract of bark, agar diffusion assay method was used.[18] For investigation of antibacterial activity, Sterile Muller Hinton agar media (Hi-media) was prepared in petridishes. The bacteria (1 × 108 bacteria/ml) was inoculated separately in the media. In each petridish, four wells (diameter 6 mm) were prepared under aseptic conditions. In these, various concentrations of the extracts were prepared (i.e., 5 μg/ml, 25 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 250 μg/ml) with DMSO. Same procedure applies in standard drug. All the dishes were incubated at 35°C for 24 hrs.

For investigation of antifungal activity, sterile potato dextrose agar media (Hi-media) were prepared in petri dishes. The fungal spores (1 × 106 spores/ml) were inoculated separately in the media. In each petri dish, four wells (diameter, 6 mm) were prepared under aseptic conditions. In these various concentrations, the extracts were prepared (i.e., 5 μg/ml, 25 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 250 μg/ml) with DMSO. Same procedures apply for standard drug. DMSO is used as a blank. All the dishes were incubated at 35°C for seven days. At the end of the incubation period, the media were observed for zone of inhibition. The zones of inhibition were measured in millimeter using Vernier Calipers.

Results

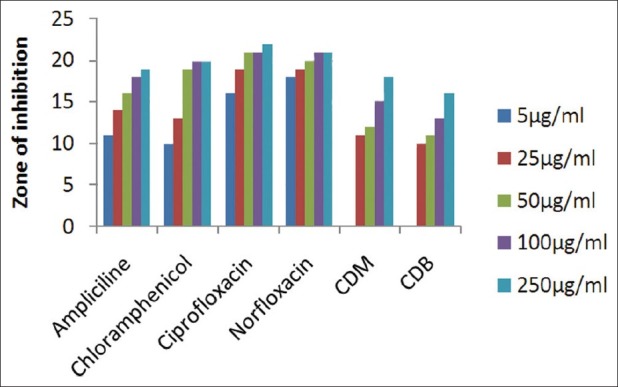

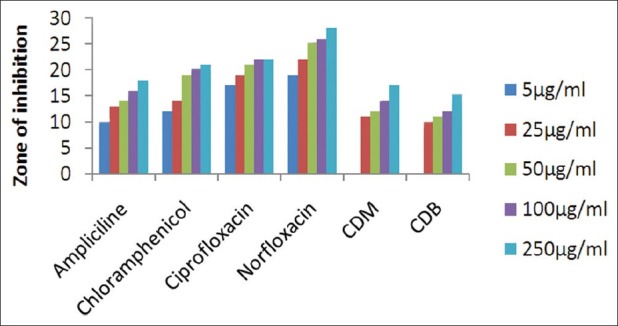

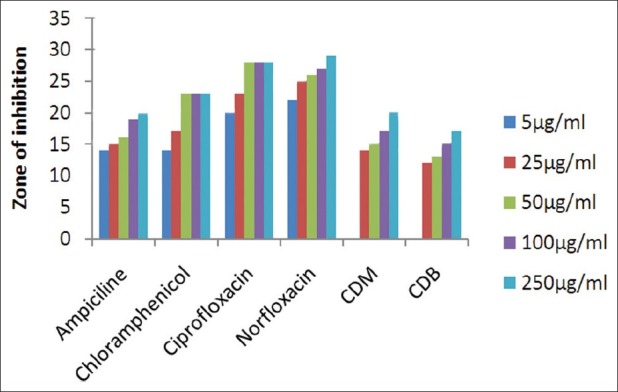

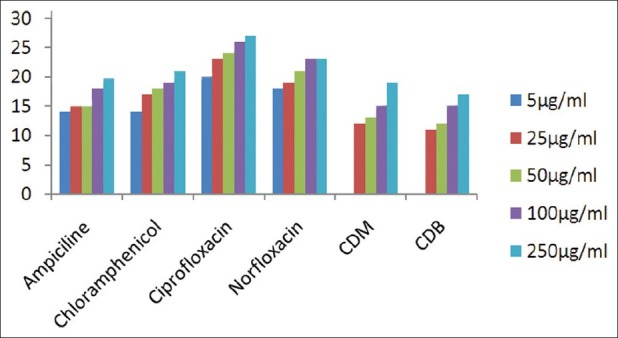

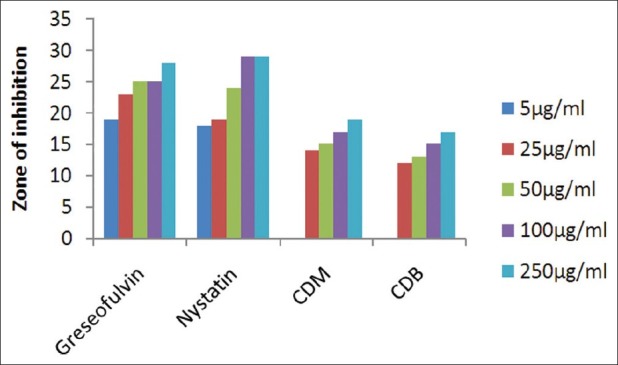

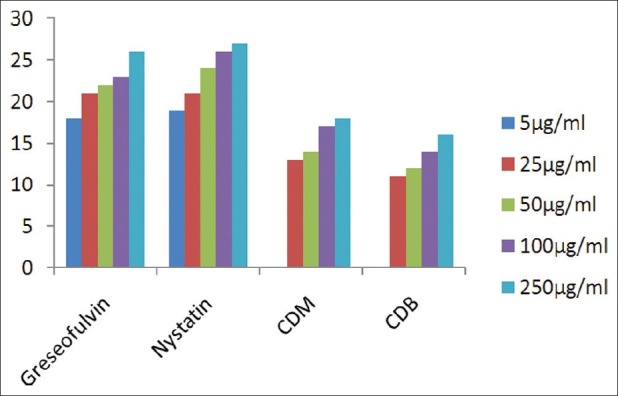

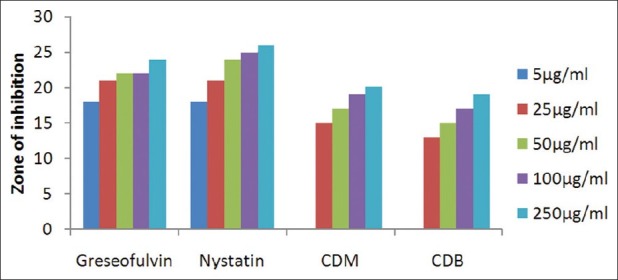

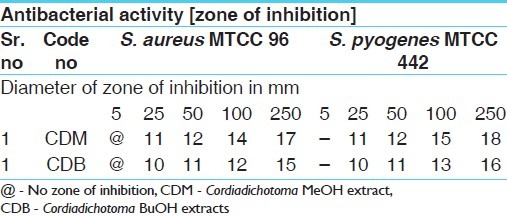

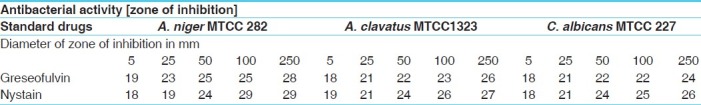

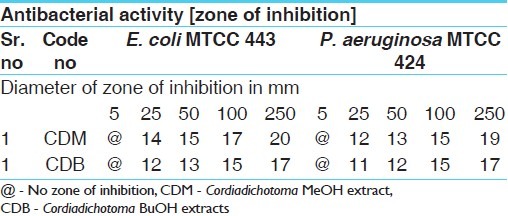

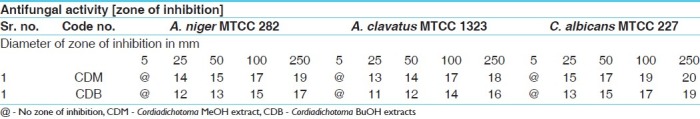

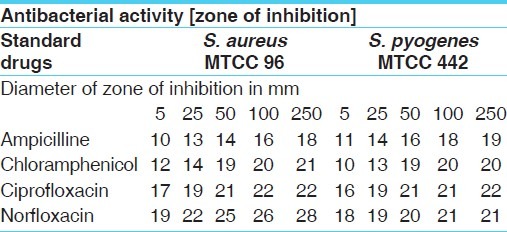

The results of investigation of antibacterial and antifungal activities of bark were studied in different concentrations (5 μg/ml, 25 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 250 μg/ml) against four pathogenic bacterial strains two gram positive- S . pyogenes MTCC 442 [Figure 1] and S. aureus MTCC 96 [Figure 2]; two gram negative- E . coli MTCC 443 [Figure 3], P. aeruginosa MTCC [Figure 4] and three fungal strains- A. niger MTCC 282 [Figure 5], A. clavatus MTCC 1323 [Figure 6], C. albicans MTCC 227 [Figure 7].

Figure 1.

Antibacterial activity against S. pyogenes (MTCC 442)

Figure 2.

Antibacterial activity against S. aureus (MTCC 96)

Figure 3.

Antibacterial activity against E. coli (MTCC 443)

Figure 4.

Antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa (MTCC 424)

Figure 5.

Antifungal activity against A. niger (MTCC 282)

Figure 6.

Antifungal activity against A. clavatus (MTCC 1323)

Figure 7.

Antifungal activity against C. albicans (MTCC 227)

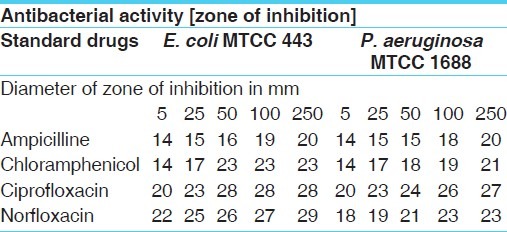

The results of the antibacterial activities are presented in Tables 1–6. The antibacterial and antifungal activity of the extract increased linearly with increase in concentration of extract (mg/ml). The results revealed that E. coli and P. aeruginosa were more sensitive as compared to S. aureus and S. pyogenes. The growth inhibition zone measured ranged from 10–20 mm for all the sensitive bacteria, and ranged from 12–21 mm for fungal strains. The antibacterial and antifungal activity of the extract increased linearly with increase in concentration of extract (mg/ml) as compared with standard drugs. For fungal activity, C. albicans shows good result as compared to A. niger and A. clavatus.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activities of MeOH and BuOH extracts of bark of CDB against gram positive organism

Table 6.

Antifungal activities of standard drugs against fungal strains

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of MeOH and BuOH extracts of bark of CDB against gram negative organism

Table 3.

Antibacterial activities of MeOH and BuOH extracts of bark of CDB against fungal organism

Table 4.

Antibacterial activities of standard drugs against gram positive organism

Table 5.

Antibacterial activities of standard drugs against gram negative test organism

The results show that Cordia dichotoma bark extracts were found to be more effective against all the microbes tested.

Discussion

Antimicrobial properties of medicinal plants are being increasingly reported from different parts of the world. World Health Organization estimates that plant extract or their active constituents are used as folk medicine in traditional therapies. In the present work, methanolic and butanol extracts obtained from bark shown remarkable activity against most of the tested bacterial and fungal strains. The results were compared with standard drugs.

Conclusion

In the current investigation, the methanolic and butanol extracts of C. dichotoma bark was found to be active on bacteria and fungi's in comparision to standard drug. The present results will form the basis for selection of plant species for further investigation in the potential discovery of new natural bioactive compounds.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Director, IPGT & RA and Vice Chancellor GAU- Jamnagar for their encouragement and providing special permission to use the research facilities to undertake this program. Authors are also thankful to Microcare laboratory, Surat, for their help to carry out the analysis.

References

- 1.Deaths by cause, sex and mortality stratum in WHORegions, estimates for 2001. World Health Report–2002. Geneva: WHO; 2002. World Health Organization (WHO) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwu MM, Duncan AR, Okunji CO. New antimicrobials of plant origin. In: Janick J, editor. Perspectives on new crops and new uses. Alexandria, VA: ASHS Press; 1999. pp. 457–62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Managing antibiotic resistance. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1961–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNeil MM, Nash SL, Hajjeh RA, Phelan MA, Conn LA, Plikaytis BD, et al. Trends in mortality due to invasive mycotic diseases in United States, 1980-1997. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:641–7. doi: 10.1086/322606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert DN, Edwards JE., Jr Is there hope for the prevention of future antimicrobial Shortages? Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:215–6. doi: 10.1086/341958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spellberg B, Powers JH, Brass EP, Miller LG, Edwards Jr., JE Trends in Antimicrobial drug developments: Implications for the future. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1279–86. doi: 10.1086/420937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: New estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ. 2003;22:151–85. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibrahim MB. Anti-microbial effects of extract leaf stem and root bark of Anogeissus Leiocarpus on Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli and Proteus Vulgaris. J Pharm Dev. 1997;2:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogundipe O, Akinbiyi O, Moody JO. Antibacterial activities of essential Ornamental plants. Niger J Nat Prod Med. 1998;2:46–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy PS, Jamil K, Madhusudhan P. Antibacterial activity of isolates from Piper Longum and Taxus baccata. Pharm Biol. 2001;39:236–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ateb DA, Erdo Urul OT. Antimicrobial activities of various medicinal and Commercial plant extracts. Turk J Biol. 2003;27:157–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwu MM, Jackson JE, Schuster BG. Medicinal plants in the fight against Leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:65–8. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parekh J, Chanda S. In vitro antifungal activity of methanol extracts of some Indian Medicinal plants against pathogenic yeast and moulds. Afr J Biotech. 2008;7:4349–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ertürk O. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of ethanolic extracts from eleven spice plants. Biologia. 2006;61:275–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Wealth of India, Raw Materials, A Dictionary of Indian Raw Material and Industrial Products. Vol. 9. New Delhi: Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; 1950. pp. 293–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian Medicinal Plants. 11th ed. Vol. 3. Uttaranchal, India: Oriental Enterprises; 1935. pp. 1029–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srivastava SK, Srivastava SD. Taxifollin 3,5-dirhamnoside from the seeds of Cordia Dichotoma. Phytochemisry. 1979;18:205–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelczar MJ, Jr, Reid RD, Chan EC. In: Microbiology. 4th ed. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill Publishing Co. Ltd; 1982. Cultivation of bacteria; p. 103. [Google Scholar]