Abstract

To evaluate the hypothesis that sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and cAMP attenuate increased permeability of individually perfused mesenteric microvessels through a common Rac1-dependent pathway, we measured the attenuation of the peak hydraulic conductivity (Lp) in response to the inflammatory agent bradykinin (BK) by either S1P or cAMP. We varied the extent of exposure to each agent (test) and measured the ratio Lptest/LpBK alone for each vessel (anesthetized rats). S1P (1 μM) added at the same time as BK (concurrent, no pretreatment) was as effective to attenuate the response to BK (Lp ratio: 0.14 ± 0.05; n = 5) as concurrent plus pretreatment with S1P for 30 min (Lp ratio: 0.26 ± 0.06; n = 11). The same pretreatment with S1P, but with no concurrent S1P, caused no inhibition of the BK response (Lp ratio 1.07 ± 0.11; n = 8). The rapid on and off action of S1P demonstrated by these results was in contrast to cAMP-dependent changes induced by rolipram and forskolin (RF), which developed more slowly, lasted longer, and resulted in partial inhibition when given either as pretreatment or concurrent with BK. In cultured endothelium, there was no Rac activation or peripheral cortactin localization at 1 min with RF, but cortactin localization and Rac activation were maximal at 1 min with S1P. When S1P was removed, Rac activation returned to control within 2 min. Because of such differing time courses, S1P and cAMP are unlikely to act through fully common effector mechanisms.

Keywords: capillaries; vascular permeability; adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate; inflammation; edema

a primary aim of this study was to test the effectiveness of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) to inhibit an acute permeability response after the S1P stimulus was withdrawn. In part this tests the general idea that increases and decreases in vascular permeability resulting from changes in perfusate S1P concentration occur more rapidly than the changes in vascular permeability when cAMP levels are modified. This is important because the action of both S1P and elevated cAMP to attenuate increased vascular permeability has been suggested to involve a common pathway that activates the small GTPase Rac1 at the endothelial periphery and stabilizes the peripheral actin structures and adhesion proteins associated with tight and adherens junctions. As a step toward further understanding this proposed common pathway, we compared changes in permeability, Rac1 activation, and junction protein distribution associated with different periods of exposure to perfusates with and without S1P and with and without the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor rolipram and the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin to modify intracellular cAMP.

The microvascular endothelium provides a regulated barrier to solute and water exchange between blood and tissue. Inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin (BK) induce an acute breakdown of the endothelial barrier through localized loss of adhesion and transient opening of small gaps between the endothelial cells. The loss of barrier integrity is a model for increased permeability in a variety of pathological states leading to edema and compromised organ function. Reports from several laboratories (3, 14, 16, 19, 23, 34) including our own demonstrate that either elevated intracellular cAMP or activation of signaling pathways by S1P in endothelial cells attenuate increased permeability induced by BK, as well as other inflammatory mediators including platelet-activating factor (PAF) and thrombin. Some of the action of elevated cAMP can be attributed to a reduction of myosin-dependent tension development in endothelial cells after exposure to agents such as thrombin (13, 29, 30). However, there is increasing evidence that the principal action of cAMP and S1P to attenuate increased vascular permeability involves regulation of adhesion between endothelial cells leading to junction complex stabilization (1, 8, 15, 21). cAMP acts via many pathways including activation of Rap1 (9), which may induce actin stabilization via Rac1 (4, 5, 7). Similarly, S1P ligation of receptor S1P1 activates a Gi/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase)/Akt-dependent pathway leading to Rac1-regulated stabilization of the peripheral actin cytoskeleton. This enhances endothelial-endothelial adhesion and attenuates acute inflammatory permeability response (17, 19). Thus activation of Rac1 to stabilize the actin cytoskeleton appears to be a common regulatory step in the inhibition of acute permeability by both S1P and cAMP (28).

Acute inhibition of the small GTPase Rac1 causes a large increase in the permeability of venular microvessels and cultured endothelial monolayers (31). Also, preferential activation of Rac by the bacterial toxin cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1 significantly attenuated permeability increase induced by PAF (32). Rac-mediated protection of the endothelial barrier against acute inflammatory stimuli is consistent with reports that S1P, which also activates Rac, protects lung permeability barrier both in vivo and in vitro (19) and with the action of Epac, a cAMP-activated exchange factor for Rap GTPase (11). We (2, 23, 34) have also shown that S1P blocks the acute permeability response to BK or PAF in individually perfused rat mesentery venules in agreement with other studies; S1P has been shown to act through receptor S1P1 in rat mesentery microvessels (34).

In a few unpublished experiments preliminary to the study of Adamson et al. (2), we observed that S1P pretreatment alone appeared to be insufficient to prevent PAF-induced acute permeability response. Rather, it seemed that the S1P had to be present in the perfusate containing PAF to have any effect. In all subsequent experiments for that study, we standardized our treatments to have a 30-min pretreatment period followed by concurrent treatment with S1P and either PAF or BK. The failure of S1P to block PAF when given as a pretreatment only (i.e., without concurrent treatment) contrasted to earlier studies (12) using rolipram and forskolin together (RF) to elevate intracellular cAMP in which we observed that the effect of RF treatment persisted and was not readily reversed. Thus we argued that further investigations of the time course of inhibition of the BK-stimulated increase in permeability by S1P and RF would provide new insight into the modulation of this proposed common pathway.

We measured microvessel hydraulic conductivity (Lp) as an index of increased vascular permeability. Experiments were designed to test the hypothesis that the action of S1P to attenuate increased permeability has a time course different from that due to elevated cAMP and may therefore not act through the same final pathway to moderate the acute permeability response. Consistent with this hypothesis, our most striking observation was that the S1P effect was very rapidly turned off when S1P was removed from the perfusate in contrast to a longer lasting effect of RF.

METHODS

Animal preparation and measurements to characterize vessel wall permeability.

Experiments were carried out on male rats anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg body wt sc) and maintained by giving additional pentobarbital (30 mg/kg sc) as needed. At the end of experiments, animals were euthanized with saturated KCl. The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996). Animal protocols (07–13052) were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis. Experiments were performed on venular mesenteric microvessels (ca. 25–35 μm diameter). Hydraulic conductivity (Lp) was measured to characterize vessel wall permeability. Experiments were based on the modified Landis technique, which measures the volume flux of water crossing the wall of a microvessel perfused via a glass micropipette following occlusion of the vessel. Assumptions and limitations have been evaluated in detail (2, 22). The initial transcapillary water flow per unit area of the capillary wall (Jv/S)0 was measured at predetermined capillary pressures of 30–60 cmH2O. Microvessel Lp was calculated as the slope of the relation between (Jv/S)0 and applied hydraulic pressure. For most experiments, (Jv/S)0 was estimated from a single occlusion with the assumption that the net effective pressure determining fluid flow was equal to the applied hydraulic pressure minus 3.6 cmH2O, the approximate oncotic pressure contributed by the BSA in all perfusates. Experimental reagents were added to the perfusate and delivered via the micropipette continuously during Lp measurement. Changes in perfusate were accomplished by withdrawing the initial micropipette and replacing it with a second micropipette filled with new perfusate solution of the appropriate composition; there was 1–2 min between removal of the previous pipette and insertion of the next pipette.

Each vessel was initially perfused with a control solution containing BSA (Sigma-Aldrich A4378) at 10 mg/ml in Ringer solution. Usually between 5 and 10 occlusions at 50 cmH2O over 10–20 min were used to establish a control Lp. Then, the first pipette was removed and a second pipette containing the BK solution was introduced at the same cannulation site. Occlusions were made every 20 to 30 s during the first 5 min of test perfusion to check for rapid change in (Jv/S)0 and then made less frequently (2–3 occlusions every 5 to 10 min) for ∼20 min while the Lp returned toward control. The second pipette was removed, a third was placed in the vessel (to establish a new baseline), and Lp was measured for 30 min. Similarly, a fourth pipette was placed in the vessel to measure the response to BK a second time in the presence or absence of appropriate modulators (specified in results).

Solutions and reagents.

Mammalian Ringer solution was composed of the following (in mM): 132 NaCl, 4.6 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 5.5 glucose, 5.0 NaHCO3, and 20 HEPES and Na-HEPES. The ratio of acid-HEPES to Na-HEPES was adjusted to achieve pH 7.40–7.45. All perfusates were mammalian Ringer solution additionally containing BSA at 10 mg/ml and test reagents or vehicle. The following stock solutions were prepared: BK (1 mM; Sigma B3259) in water, S1P (1 mM; Sigma S9666) in EtOH, rolipram (50 mM; Biomol PD-175) in EtOH, and forskolin (25 mM; Biomol CN-100) in EtOH. Concentrations in final perfusates were 10 nM BK, 1 μM S1P (5 μM in 1 group as noted), 10 μM rolipram, and 5 μM forskolin. EtOH was added as appropriate to all control solutions.

Analysis and statistics.

To examine the modulation of response to BK, we tested the response in each vessel twice, first in the absence of other agents and second in the presence of a test reagent. Therefore, each vessel acted as its own control. Throughout, averaged Lp values were reported as means ± SE. Summary data are expressed as the ratio of the peak Lp value measured during the second BK exposure to the peak value measured during the first BK perfusion. The indicated statistical tests were performed assuming significance for probability levels <0.05.

Cell culture and Rac activation assay.

Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECd; Clonetics) were seeded at high density (near confluence) on collagen-coated tissue culture treated polystyrene and cultured for up to 3 days. HMVECd were serum starved for 16 h before treatment with RF or vehicle. The relative level of Rac-GTP was determined using a colorimetric ELISA based assay (Rac1,2,3 activation assay; Cytoskeleton). Samples were processed according to manufacturer's protocol.

Confocal microscopy of immunolabeled HMVECd.

Cultures were flooded with ice-cold fixative, incubated with primary antibodies against vascular endothelial-cadherin (goat polyclonal, sc6458; Santa Cruz) and cortactin (mouse monoclonal, clone 4F11; Upstate), labeled with fluorescent secondary antibodies, and then mounted for confocal microscopy.

RESULTS

Inhibition of BK induced increases in hydraulic conductivity by S1P.

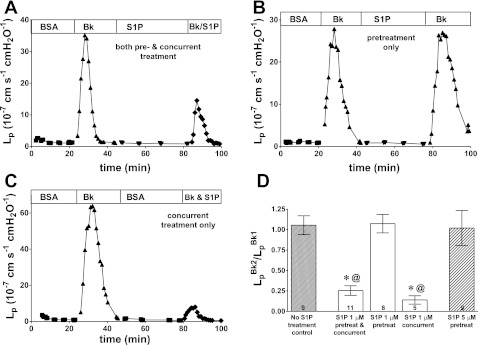

BK (10 nM) induced a transient increase in Lp that reached a peak response within 2–3 min. In the first group of vessels, S1P (1 μM) was given as a pretreatment (30 min) before removal of the perfusion pipette and recannulation with the test pipette containing both BK and S1P. This combination of both pretreatment and concurrent treatment was the standardized application of S1P used in previous studies. Representative data from one experiment show that the increase in Lp induced by the second BK treatment is partially inhibited by the S1P (Fig. 1A). With this protocol, the second response to BK was on average 25% of the first response (0.26 ± 0.06; n = 11). When using the same sequence of perfusions but omitting the S1P from the second treatment with BK, we found a very different result. A representative experiment using this pretreatment-only protocol is shown in Fig. 1B where there is no inhibition of the BK response despite 30 min of S1P pretreatment. In control experiments where BK was administered twice in the complete absence of S1P with the same timing, there was no difference between the average responses to BK (2).

Fig. 1.

Representative data show that sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) efficacy depends strongly on timing of application. A: S1P applied both as pretreatment and concurrent with second bradykinin (BK) test inhibited the acute BK response relative to first BK. B: S1P given only as pretreatment yielded no inhibitory action toward BK. C: S1P applied concurrent only with BK strongly inhibited the BK response. S1P was 1 μM and BK was 10 nM in each experiment. D: pretreatment alone (either 1 μM or 5 μM) showed no inhibition of the BK peak hydraulic conductivity (Lp) response. Concurrent treatment alone and the combined pre- and concurrent treatment both strongly inhibited BK but were not statistically different from one another. Values are means ± SE with number of vessels in each group shown at base of bars; significance assumed for *P < 0.05, different from no treatment control; @P < 0.05, different from S1P pretreatment (1 μM) by unpaired t-test.

We reasoned that if the result of Fig. 1B indicates that the effect of S1P is very rapidly lost (or turned off) during the ∼1- to 2-min recannulation period, then the inhibitory effect seen in Fig. 1A must indicate a very rapid onset of inhibitory activity during the S1P exposure concurrent with BK. Therefore, in the next group of experiments, the vessels were not pretreated with S1P. After a 30-min period of perfusion with vehicle solution, each vessel was tested with BK in the presence of S1P (concurrent-only treatment group). Representative data from one experiment are shown in Fig. 1C. As predicted, vessels in this group showed strong inhibition despite having no pretreatment period with S1P.

The averaged data for all experimental groups (Fig. 1D) demonstrate that the S1P pretreatment-only protocol had no inhibitory effect on the subsequent BK test whereas the S1P concurrent treatment (no pretreatment) significantly attenuated increased permeability relative to pretreatment alone. Furthermore, the concurrent treatment group was attenuated (0.14 ± 0.05) to the same extent (with a somewhat lower mean, but not statistically different) as the group receiving both pretreatment and concurrent treatment (0.26 ± 0.06). Most important, both of these groups are significantly different from the pretreatment only group, which showed no inhibition. These results demonstrated two points: 1) that the action of 1 μM S1P to strongly attenuate increased permeability is developed within the first 1–2 min of contact with the microvessels, and 2) that the effect of S1P pretreatment is rapidly lost. The latter point is tested using cultured monolayers below. Also, shown in Fig. 1D are data for a group of vessels pretreated-only with 5 μM S1P. There was no inhibition in the vessels treated with 5 μM S1P, indicating that the lack of response in the 1 μM S1P pretreatment-only group did not result from too low a concentration of S1P to cause inhibition.

Inhibition of BK induced increases in hydraulic conductivity with elevated cAMP.

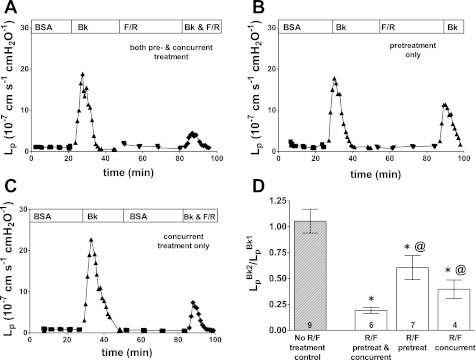

Because endothelial cells exposed to rolipram show rapid increases in intracellular cAMP (33), we used the combination of RF previously used in our laboratory to increase intracellular cAMP (1, 3). In each microvessel, the transient increase in Lp after exposure to BK was first measured. Subsequent perfusions were similar in design to those used for S1P. Representative data from one experiment shown in Fig. 2A demonstrate the strong inhibitory effect of RF on BK-induced increased permeability where the microvessels were both pretreated with RF and treated with RF concurrent with the second BK test.

Fig. 2.

Representative data show that cAMP efficacy is not strongly dependent on timing of application. A: when given both as pretreatment and concurrent with BK, the rolipram/forskolin combination provided strong inhibition of the BK Lp response. B: applied as pretreatment only, the rolipram and forskolin (RF) partially inhibited BK. C: applied concurrently only, RF treatment also partially inhibited BK. Rolipram was 10 μM, forskolin was 5 μM, and BK was 10 nM in each experiment. D: all groups showed partial inhibition. Values are means ± SE with number of vessels in each group shown at base of bars; significance assumed for *P < 0.05, different from no treatment control, @P < 0.05, different from “RF pretreat & concurrent” by unpaired t-test.

In the second group of vessels, the RF was given as a pretreatment only before the test perfusion with BK. The RF had a partial inhibitory effect that suppressed only ∼40% of the Lp response. A representative experiment is shown in Fig. 2B. The combination of a partial inhibitory effect with pretreatment only and a strong inhibition with both pretreatment and concurrent treatment suggested that concurrent treatment alone would also provide partial inhibition. Therefore, the third group was treated with RF concurrently with the BK (that is, with no RF pretreatment). Representative data shown in Fig. 2C illustrate the intermediate effect of concurrent RF treatment to inhibit BK.

A summary of the RF data is in Fig. 2D where the most striking difference from the S1P results is that RF pretreatment alone yields a significant inhibition relative to the no treatment control. Also different from the S1P results is that the combination of both treatments (pretreatment and concurrent) was significantly more effective than either pretreatment or concurrent treatment alone.

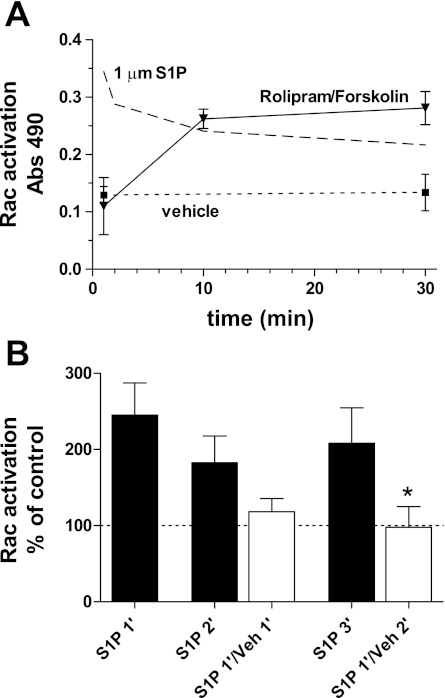

Rac activation and cortactin localization to endothelial periphery.

In a previous study (2), we examined the time course of Rac activation in endothelium resulting from stimulation with S1P. To extend the comparison with those previous results here we tested for the activation of Rac in cultured endothelial cells (HMVECd) during treatment with RF. At 1 min, the assay for Rac was not different from vehicle control. At 10 min, activation was significantly increased and stayed at that level for up to 30 min (Fig. 3A). This was in strong contrast to the results seen with S1P for which Rac activation was maximal at 1 min and declined over the subsequent 30 min.

Fig. 3.

Activation of Rac using either RF or S1P in cultured human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECd). A: activation of Rac by RF treatment was not seen at 1 min of treatment but rose to near maximal by 10 min, remaining constant up to 30 min. Vehicle treatment shows control activation level. Pattern of activation by S1P is indicated by upper dashed line (Ref. 2). Values are mean ± SE; minimum number of independent observations in each group was 4. B: Rac activation by S1P (1 μM) was ∼200% of control when present for 1, 2, or 3 min (filled bars). Off response shown by exposing cells to S1P for 1 min and then switching to vehicle for 1 or 2 min (open bars); the Rac activation returns toward control levels and was significantly different from continuous S1P (*P < 0.05, one-tailed Student's t-test; n = 4 in each group).

Because S1P had no effect in vivo when it was given as a pretreatment only (Fig. 1), we predicted that Rac activation was rapidly turned off when the S1P stimulus was removed. We tested this prediction by treating HMVECd monolayers with S1P for 1 min and replacing S1P with vehicle solution for 1 or 2 min before measuring Rac activation. The results clearly showed that Rac activation returned to control level within 1–2 min after withdrawing the S1P (Fig. 3B, open bars). RF was not tested in this manner because there was no indication from the in vivo studies that the RF effect diminished over time.

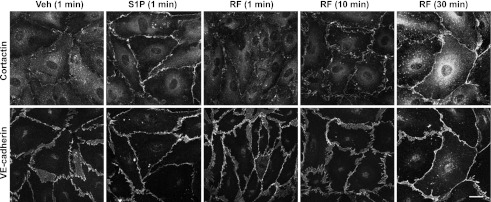

We (2) previously demonstrated that S1P inhibition of the acute BK permeability response was associated with a rapid (≤1 min) and distinct cortactin localization to the endothelial periphery. To test for cortactin localization in response to cAMP, we exposed cultured endothelial cells (HMVECd) to RF using the same concentrations as applied to single vessels (and same as used for the Rac activation studies above) for 1, 10, or 30 min. At 1 min, there was no noticeable increase in localization relative to vehicle controls, while at 10 and 30 min there was a strong localization to the endothelial periphery (Fig. 4). The localization of cortactin associated with RF treatment paralleled in time the increase in Rac activation in contrast to the very rapid onset of Rac activation and the rapid localization of cortactin seen with S1P treatment (2).

Fig. 4.

Localization of cortactin subsequent to RF treatment. At 1 min of RF the cortactin was not different from control. Cortactin at 10 or 30 min of RF was strongly peripheral. S1P for 1 min stimulated very strong peripheral localization of cortactin compared with vehicle control. Vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin demonstrated endothelial periphery and showed no changes under these conditions. Scale bar = 20 μm all panels.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals several novel observations that differentiate the actions of S1P from those of cAMP regarding the inhibition of the acute endothelial inflammatory response to bradykinin. The experiments using S1P given concurrent with BK in the absence of any pretreatment showed strong inhibition of the increased Lp response induced by BK and thereby clearly indicated that the inhibitory effect of S1P was turned on very rapidly. The experiments with S1P given for a 30-min pretreatment, then removed for 1–2 min before BK, showed no inhibition at all and tell us that the S1P effect was turned off very rapidly. The combination of pretreatment and concurrent treatment, while having a slightly lower mean BK response, was not significantly different from concurrent treatment alone. This result was consistent with the observation that pretreatment had no significant effect when removed for as little as 1 min. Therefore, the S1P effect can be turned on very fast but is highly transitory. Similar experiments with RF to increase intracellular cAMP yielded a very different pattern. When given only concurrent with BK the RF induced a partial inhibition, showing that the full inhibition by cAMP does not develop immediately. RF also caused a partial inhibition when given as a pretreatment only, indicating that the effect is not quickly lost. When given as both a pretreatment and concurrent with the BK, RF provided the strongest inhibition. Taken together these experiments indicate that the effects of RF build up more slowly than those of S1P and are longer lasting. We also found that RF gradually induced both Rac activation and cortactin localization during a 30-min treatment but that neither was visible at 1 min in strong contrast to our results with S1P, where both cortactin localization and Rac activation were maximal at 1 min and diminished over a 30-min treatment (2). Finally, we demonstrated that Rac activation, which turns on very rapidly with S1P, returned to control level within 1–2 min when S1P was removed after a 1-min stimulus.

Before examining the results relative to previous studies, it is important to clarify that the perfusion technique used in these studies relies on multiple sequential cannulations of the individual vessel with individual glass micropipettes. This “modified Landis” technique has been extensively tested and validated for measurement of Lp and provides both control measurement and test measurement in each vessel (22). Moreover, the responses to BK and inhibition by S1P and RF, when using the combined pre- and concurrent treatment, have been investigated and the methodology validated (2, 3, 23, 34). In the present design after measurements were made with a given perfusion solution, the micropipette is removed from the vessel and the next solution is introduced into the vessel at the same location using a new micropipette. During the 1–2 min that it takes to replace the pipette the vessel refills with blood, perfusion with artificial solution is not continuous. This 1–2 min was apparently sufficient time for the effect to be “turned off.” Therefore, it is consistent with the technique that the combination of S1P pretreatment and concurrent treatment is not statistically different from concurrent treatment alone and that both block the acute BK response due to the presence of S1P concurrent with the BK. That pretreatment alone with RF does inhibit BK is clear evidence that the RF treatment to increase cAMP persists for at least several minutes.

The rapid onset of S1P inhibition in microvessels corresponds to our previous observations in cultured endothelial cells that Rac activation peaks within 1 min of S1P application and is associated with cortactin localization to the endothelial periphery (2). Other studies, all using cultured endothelium, note that Rac is activated, monolayer electrical resistance increases within 1 min, and that actin is organized to the cell periphery within 5 min (14). Garcia et al. (14) also found that S1P applied simultaneously with thrombin negated the loss of electrical resistance that was measured with thrombin alone. Studies (1, 23, 34) of the permeability modulating effects of S1P in vivo have generally demonstrated attenuation of hyperpermeability with pretreatment (20- to 30-in period before exposure to PAF or BK) or when given an hour after injury in the lung induced by LPS or induction of edema and protein leak by mechanical ventilation (20, 24). However, no definite conclusions can be drawn regarding how long the inhibition lasts. Our results (Fig. 1, B and D) are the clearest to date that S1P effectively inhibits the acute permeability response in vivo only while it is present and its efficacy is rapidly lost when S1P is withdrawn. Moreover, our results, demonstrating a rapidly responsive variability of S1P effect, correspond to the concept that physiological S1P levels maintain a basal tone via action of the S1P1 receptor; only at high (supraphysiological) S1P concentrations are receptors internalized and degraded sufficiently to interfere with basal tone (18, 25).

In the perfused microvessels, we found that RF as a pretreatment alone retains some lasting effect after having been withdrawn for 1–2 min in contrast to the S1P effect that was completely lost. When given as both pretreatment and concurrent with BK, the inhibition was strongest, indicating that the cAMP effect develops slowly and lasts longer than S1P inhibition. A simple explanation for the slower activation could be that cAMP levels rise slowly under RF stimulation. However, we note that in cultured endothelial cells exposed to forskolin or isoproterenol cAMP rises to near maximal level within 60–100 s (5, 33), so it seems unlikely that slow activation of cAMP accounts for the difference. With regard to the slow loss of inhibition, it is possible that the RF effect lasts longer than S1P due to slow degradation of cAMP, but we are unaware of any data directly addressing this possibility; the rapidity of cAMP decrease is not known.

cAMP and S1P both stimulate Rac activation (6, 14). Also, inhibition of Rac activation was found to strongly inhibit cAMP barrier enhancement stimulated by RF, further indicating that cAMP and S1P act through a common pathway that converges on Rac (27). Our observation that the effect of cAMP does not turn off as rapidly as that of S1P suggests that some separate pathway to stabilize endothelial junctions is affected by cAMP. Recent studies (7, 26) indicate that VASP augments a PKA-dependent barrier enhancement in part via a parallel pathway possibly involving integrin recruitment to para-junctional regions, thus providing a possible mechanism by which cAMP could provide stronger and longer lasting junctional stability than S1P.

In summary, because the cAMP inhibition and the S1P inhibition of BK have differing time courses, it is likely that they are not acting through a fully common effector mechanism. We particularly note the contrast between the slow Rac activation and cortactin localization that develops over 30 min found with RF stimulation of cAMP pathways and our previous report of rapid Rac activation (1 min) and the associated rapid cortactin localization resulting from S1P stimulation. Perhaps even more striking is the immediate loss of inhibitory efficacy towards BK hyperpermeability on the removal of S1P, which contrasts with the lasting effect of cAMP when stimulated with RF. The short-lived efficacy of S1P inhibition in vivo corresponds to the rapid off-response of the S1P stimulated Rac activation demonstrated in cultured endothelium. While our results clearly indicate that the venular microvascular inhibitory efficacy of S1P is short-lived, they do not rule out possible longer lasting effects when injected systemically (20, 24). Nonetheless, these results suggest that therapeutic manipulation of S1P pathways to prevent or recover from inflammation will require a continuous source of S1P to maintain low permeability in microvessels (10, 25). Modulation of downstream effectors, particularly those involving the full effect of cAMP pathways, may have more long-lasting effect.

GRANTS

Support for this work was provided by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-28607 and HL-44485.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.A., R.K.S., J.F.C., T.L.T., and F.E.C. conception and design of research; R.A., R.K.S., J.F.C., A.A., and T.L.T. performed experiments; R.A., R.K.S., J.F.C., A.A., and T.L.T. analyzed data; R.A., J.F.C., A.A., T.L.T., and F.E.C. interpreted results of experiments; R.A. prepared figures; R.A. and F.E.C. drafted manuscript; R.A., J.F.C., and F.E.C. edited and revised manuscript; R.A., R.K.S., J.F.C., A.A., T.L.T., and F.E.C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamson RH, Ly JC, Sarai RK, Lenz JF, Altangerel A, Drenckhahn D, Curry FE. Epac/Rap1 pathway regulates microvascular hyperpermeability induced by PAF in rat mesentery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1188– H1196, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adamson RH, Sarai RK, Altangerel A, Thirkill TL, Clark JF, Curry FR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate modulation of basal permeability and acute inflammatory responses in rat venular microvessels. Cardiovasc Res 88: 344– 351, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adamson RH, Zeng M, Adamson GN, Lenz JF, Curry FE. PAF- and bradykinin-induced hyperpermeability of rat venules is independent of actin-myosin contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H406– H417, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arthur WT, Quilliam LA, Cooper JA. Rap1 promotes cell spreading by localizing Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factors. J Cell Biol 167: 111– 122, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baumer Y, Spindler V, Werthmann RC, Bunemann M, Waschke J. Role of Rac 1 and cAMP in endothelial barrier stabilization and thrombin-induced barrier breakdown. J Cell Physiol 220: 716– 726, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Birukova AA, Burdette D, Moldobaeva N, Xing J, Fu P, Birukov KG. Rac GTPase is a hub for protein kinase A and Epac signaling in endothelial barrier protection by cAMP. Microvasc Res 79: 128– 138, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birukova AA, Zagranichnaya T, Alekseeva E, Bokoch GM, Birukov KG. Epac/Rap and PKA are novel mechanisms of ANP-induced Rac-mediated pulmonary endothelial barrier protection. J Cell Physiol 215: 715– 724, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bogatcheva NV, Verin AD. The role of cytoskeleton in the regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function. Microvasc Res 76: 202– 207, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bos JL. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 733– 738, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Camerer E, Regard JB, Cornelissen I, Srinivasan Y, Duong DN, Palmer D, Pham TH, Wong JS, Pappu R, Coughlin SR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in the plasma compartment regulates basal and inflammation-induced vascular leak in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 1871– 1879, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cullere X, Shaw SK, Andersson L, Hirahashi J, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function by Epac, a cAMP-activated exchange factor for Rap GTPase. Blood 105: 1950– 1955, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fu BM, Adamson RH, Curry FE. Test of a two-pathway model for small-solute exchange across the capillary wall. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H2062– H2073, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garcia JG, Davis HW, Patterson CE. Regulation of endothelial cell gap formation and barrier dysfunction: role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Cell Physiol 163: 510– 522, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garcia JG, Liu F, Verin AD, Birukova A, Dechert MA, Gerthoffer WT, Bamberg JR, English D. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by Edg-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Clin Invest 108: 689– 701, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kooistra MR, Corada M, Dejana E, Bos JL. Epac1 regulates integrity of endothelial cell junctions through VE-cadherin. FEBS Lett 579: 4966– 4972, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee JF, Gordon S, Estrada R, Wang L, Siow DL, Wattenberg BW, Lominadze D, Lee MJ. Balance of S1P1 and S1P2 signaling regulates peripheral microvascular permeability in rat cremaster muscle vasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H33– H42, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee JF, Ozaki H, Zhan X, Wang E, Hla T, Lee MJ. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling regulates lamellipodia localization of cortactin complexes in endothelial cells. Histochem Cell Biol 126: 297– 304, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lucke S, Levkau B. Endothelial functions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell Physiol Biochem 26: 87– 96, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McVerry BJ, Garcia JG. In vitro and in vivo modulation of vascular barrier integrity by sphingosine 1-phosphate: mechanistic insights. Cell Signal 17: 131– 139, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McVerry BJ, Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, Simon BA, Garcia JG. Sphingosine 1-phosphate reduces vascular leak in murine and canine models of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 987– 993, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev 86: 279– 367, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michel CC, Curry FE. Microvascular permeability. Physiol Rev 79: 703– 761, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Minnear FL, Zhu L, He P. Sphingosine 1-phosphate prevents platelet-activating factor-induced increase in hydraulic conductivity in rat mesenteric venules: pertussis toxin sensitive. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H840– H844, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, McVerry BJ, Burne MJ, Rabb H, Pearse D, Tuder RM, Garcia JG. Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169: 1245– 1251, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosen H, Gonzalez-Cabrera P, Marsolais D, Cahalan S, Don AS, Sanna MG. Modulating tone: the overture of S1P receptor immunotherapeutics. Immunol Rev 223: 221– 235, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schlegel N, Waschke J. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein: crucial for activation of Rac1 in endothelial barrier maintenance. Cardiovasc Res 87: 1– 3, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schlegel N, Waschke J. VASP is involved in cAMP-mediated Rac 1 activation in microvascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C453– C462, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spindler V, Schlegel N, Waschke J. Role of GTPases in control of microvascular permeability. Cardiovasc Res 87: 243– 253, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stelzner TJ, Weil JV, O'Brien RF. Role of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in the induction of endothelial barrier properties. J Cell Physiol 139: 157– 166, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VW. Targets for pharmacological intervention of endothelial hyperpermeability and barrier function. Vascul Pharmacol 39: 257– 272, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Waschke J, Baumgartner W, Adamson RH, Zeng M, Aktories K, Barth H, Wilde C, Curry FE, Drenckhahn D. Requirement of Rac activity for maintenance of capillary endothelial barrier properties. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H394– H401, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Waschke J, Burger S, Curry FR, Drenckhahn D, Adamson RH. Activation of Rac-1 and Cdc42 stabilizes the microvascular endothelial barrier. Histochem Cell Biol 125: 397– 406, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Werthmann RC, von Hayn K, Nikolaev VO, Lohse MJ, Bunemann M. Real-time monitoring of cAMP levels in living endothelial cells: thrombin transiently inhibits adenylyl cyclase 6. J Physiol 587: 4091– 4104, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang G, Xu S, Qian Y, He P. Sphingosine-1-phosphate prevents permeability increases via activation of endothelial sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 in rat venules. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1494– H1504, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]