Abstract

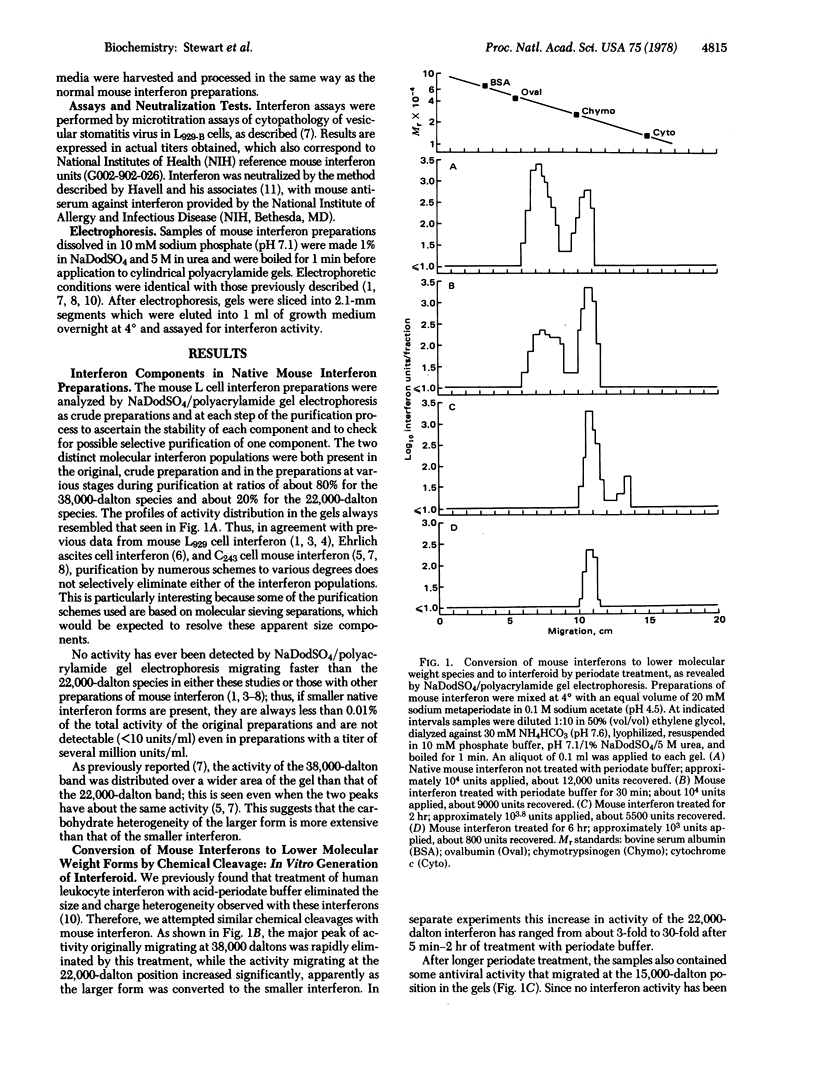

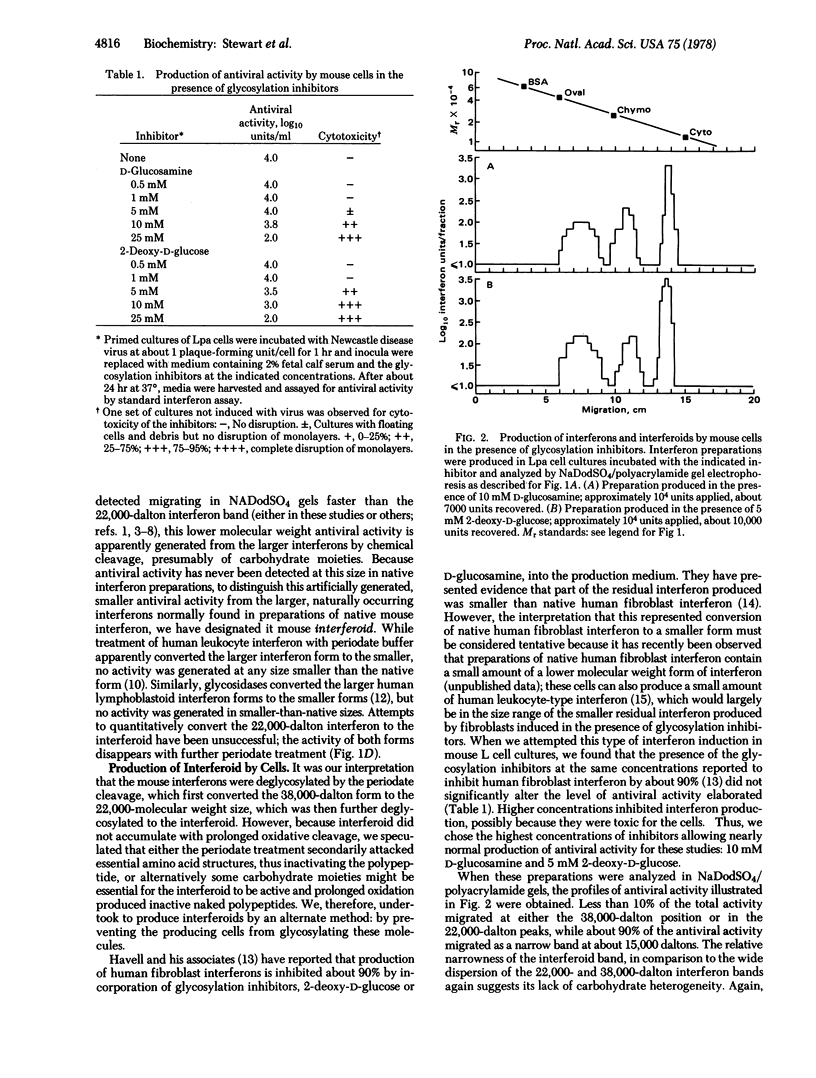

Mouse interferons appear as two distinct molecular forms, one migrating at 38,000 daltons in sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gels and one migrating at 22,000 daltons; these interferons comprise about 80% and 20% of total activities, respectively. When such interferon preparations are briefly exposed to acidic periodate buffer, the larger interferon species is apparently converted to the smaller form since the activity at 38,000 daltons is completely eliminated while the activity at 22,000 daltons increases significantly; upon further oxidative cleavage, antiviral activity becomes detectable migrating at 15,000 daltons. Because no native mouse interferon has been reported as such small molecules, this antiviral activity is designated mouse “interferoid” to distinguish it from the native, naturally occurring interferon forms. Prolonged acidperiodate treatment fails to quantitatively convert the 22,000-dalton interferon to the 15,000-dalton interferoid since both are inactivated. When L cells are induced to make interferon in the presence of glycosylation inhibitors, either D-glucosamine or 2-deoxy-D-glucose, they produce approximately normal levels of antiviral activity. However, when such preparations are analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, little activity (<10%) migrates as either the 38,000-dalton or 22,000-dalton native interferons. The interferons and interferoid are antigenically and hydrophobically indistinguishable. These data suggest that induced mouse cells normally synthesize the interferoid as a precursor polypeptide that is either partially or extensively modified by carbohydrate additions to produce, respectively, the 22,000- and 38,000-dalton mouse interferons. Because interferoid is apparently fully biologically active without these moieties, chemical synthesis of such unmodified polypeptides or active fragments from them appears feasible.

Keywords: sodium dodecyl sulfate, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, deglycosylation, glycoproteins, precursor protein

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bridgen P. J., Anfinsen C. B., Corley L., Bose S., Zoon K. C., Rüegg U. T., Buckler C. E. Human lymphoblastoid interferon. Large scale production and partial purification. J Biol Chem. 1977 Oct 10;252(19):6585–6587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter W. A. Interferon: evidence for subunit structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970 Oct;67(2):620–628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.2.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri R. L., Havell E. A., Vilcek J., Pestka S. Synthesis of human interferon by Xenopus laevis oocytes: two structural genes for interferons in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Aug;74(8):3287–3291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maeyer-Guignard J., Tovey M. G., Gresser I., De Maeyer E. Purification of mouse interferon by sequential affinity chromatography on poly(U)--and antibody--agarose columns. Nature. 1978 Feb 16;271(5646):622–625. doi: 10.1038/271622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmyter J., Stewart W. E., 2nd Molecular modification of interferon: attainment of human interferon in a conformation active on cat cells but inactive on human cells. Virology. 1976 Apr;70(2):451–458. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresser I., Maury C., Tovey M., Morel-Maroger L., Pontillon F. Progressive glomerulonephritis in mice treated with interferon preparations at birth. Nature. 1976 Sep 30;263(5576):420–422. doi: 10.1038/263420a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresser I., Tovey M. G., Maury C., Chouroulinkov I. Lethality of interferon preparations for newborn mice. Nature. 1975 Nov 6;258(5530):76–78. doi: 10.1038/258076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havell E. A., Berman B., Ogburn C. A., Berg K., Paucker K., Vilcek J. Two antigenically distinct species of human interferon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975 Jun;72(6):2185–2187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havell E. A., Hayes T. G., Vilcek J. Synthesis of two distinct interferons by human fibroblasts. Virology. 1978 Aug;89(1):330–334. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havell E. A., Vilcek J., Falcoff E., Berman B. Suppression of human interferon production by inhibitors of glycosylation. Virology. 1975 Feb;63(2):475–483. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havell E. A., Yamazaki S., Vilcek J. Altered molecular species of human interferon produced in the presence of inhibitors of glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 1977 Jun 25;252(12):4425–4427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakita M., Cabrer B., Taira H., Rebello M., Slattery E., Weideli H., Lengyel P. Purification of interferon from mouse Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 1978 Jan 25;253(2):598–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight E., Jr Heterogeneity of purified mouse interferons. J Biol Chem. 1975 Jun 10;250(11):4139–4144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paucker K., Dalton B. J., Törmä E. T., Ogburn C. A. Biological properties of human leukocyte interferon components. J Gen Virol. 1977 May;35(2):341–351. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-35-2-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W. E., 2nd, Desmyter J. Molecular heterogeneity of human leukocyte interferon: two populations differing in molecular weights, requirements for renaturation, and cross-species antiviral activity. Virology. 1975 Sep;67(1):68–73. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W. E., 2nd Distinct molecular species of interferons. Virology. 1974 Sep;61(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W. E., 2nd, Gosser L. B., Lockart R. Z., Jr Priming: a nonantiviral function of interferon. J Virol. 1971 Jun;7(6):792–801. doi: 10.1128/jvi.7.6.792-801.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W. E., 2nd, Gresser I., Tovey M. G., Bandu M., Le Goff S. Identification of the cell multiplication inhibitory factors in interferon preparations as interferons. Nature. 1976 Jul 22;262(5566):300–302. doi: 10.1038/262300a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W. E., 2nd, LeGoff S., Wiranowska-Stewart Characterization of two distinct molecular populations of type I mouse interferons. J Gen Virol. 1977 Nov;37(2):277–284. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-37-2-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W. E., 2nd, Lin L. S., Wiranowska-Stewart M., Cantell K. Elimination of size and charge heterogeneities of human leukocyte interferons by chemical cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Oct;74(10):4200–4204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcek J., Havell E. A., Yamazaki S. Antigenic, physicochemical, and biologic characterization of human interferons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1977 Mar 4;284:703–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb22006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Kawade Y. Purification of two components of mouse L cell interferon: electrophoretic demonstration of interferon proteins. J Gen Virol. 1976 Nov;33(2):225–236. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-33-2-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]