Abstract

Ligand-gated cation channels are a frequent component of signaling cascades in eukaryotes. Eukaryotes contain numerous diverse gene families encoding ion channels, some of which are shared and some of which are unique to particular kingdoms. Among the many different types are cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGCs). CNGCs are cation channels with varying degrees of ion conduction selectivity. They are implicated in numerous signaling pathways and permit diffusion of divalent and monovalent cations, including Ca2+ and K+. CNGCs are present in both plant and animal cells, typically in the plasma membrane; recent studies have also documented their presence in prokaryotes. All eukaryote CNGC polypeptides have a cyclic nucleotide-binding domain and a calmodulin binding domain as well as a six transmembrane/one pore tertiary structure. This review summarizes existing knowledge about the functional domains present in these cation-conducting channels, and considers the evidence indicating that plant and animal CNGCs evolved separately. Additionally, an amino acid motif that is only found in the phosphate binding cassette and hinge regions of plant CNGCs, and is present in all experimentally confirmed CNGCs but no other channels was identified. This CNGC-specific amino acid motif provides an additional diagnostic tool to identify plant CNGCs, and can increase confidence in the annotation of open reading frames in newly sequenced genomes as putative CNGCs. Conversely, the absence of the motif in some plant sequences currently identified as probable CNGCs may suggest that they are misannotated or protein fragments.

Keywords: amino acid motif, CNGC, cyclic nucleotide-binding domain, calmodulin binding domain, Ca2+ signaling, ion channel, cyclic nucleotide, channel evolution

Plant cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels (CNGCs) comprise a large family of non-selective cation-conducting channels in plants. Of the 56 coding sequences identified at present as cation-conducting channels in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome, 20 are members of the CNGC family (Ward et al., 2009). CNGCs have been functionally characterized by expression in heterologous systems, or by analysis of cation-related phenotypes of mutant plants (typically A. thaliana) that have specific CNGC genes silenced (Talke et al., 2003; Ma et al., 2010). All relevant experimental evidence indicates that plant CNGCs are specifically localized to the plasma membrane, although CNGC20 may be targeted to the chloroplast envelope according to a putative annotation in UniProt1 (accessed August 28, 2011). Functional analyses of members of this channel family have associated many of them with inward K+ and Ca2+currents, and at least in several cases, Na+ conductance (Ma et al., 2010). It may be relevant to their function in plants that in one case, K+ conductance by a CNGC was restricted in the presence of millimolar concentrations of external Ca2+ (Leng et al., 2002). Ca2+ block of monovalent cation conductance is central to the function of animal CNGCs (Alam et al., 2007). CNGC function in plant biology may be more related to their ability to conduct Ca2+ rather than monovalent cations into plant cells. Abdel-Hamid et al. (2011) provide additional evidence consistent with this conjecture.

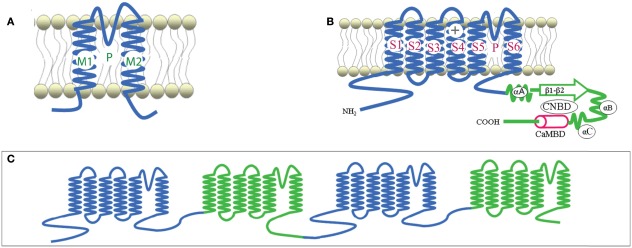

Plant CNGCs were first identified as such by the presence of a cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (CNBD), and by their overall structural similarity to animal CNGCs (Talke et al., 2003). CNGCs have also recently been identified in prokaryotes (Nimigean et al., 2004; Kuo et al., 2007), although the prokaryote channel primary sequences show some notable differences in their functional domains (Cukkemane et al., 2011). The most conserved region of the CNGC CNBD is a phosphate binding cassette (PBC) which binds the sugar and phosphate moieties of the cyclic nucleotide (cNMP) ligand (Cukkemane et al., 2011). A “hinge” region adjacent to the PBC is also conserved and is thought to contribute to ligand binding efficacy and selectivity (Young and Krougliak, 2004). The hinge affects cAMP and cGMP activation by modifying the energy requirement of ligand binding and does so independently from other regions (i.e., structural motifs) of the animal CNBD (Young and Krougliak, 2004). Young and Krougliak (2004) modified residues in the hinge, affecting cNMP dependent gating of the channel without causing structural changes in other regions of the CNBD. Additional features of the CNBD of plant CNGCs will be discussed below. Like animal CNGCs, plant CNGCs are members of the “P-loop” superfamily of cation channels present in all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (Ward et al., 2009). P-loop channels arose early in evolution and their structure provides a basic form that has evolved to give rise to channels capable of conducting various cations, thereby fulfilling a broad range of functions in cells (Zhorov and Tikhonov, 2004). The core primary structure of a P-loop channel polypeptide (Figure 1A) can be represented by two α helices forming membrane-spanning domains (M1 and M2 in Figure 1A) surrounding a membrane re-entering pore loop (P-loop; “P” in Figure 1A). Alternatively, this core structure can also be formed by a polypeptide with six transmembrane (TM) regions (S1–S6 in Figure 1B); in this case the P-loop is present between the fifth (S5) and sixth (S6) transmembrane regions. The amino (N)- and carboxyl (C)-termini are both on the same side of the membrane, and typically cytosolic. The highly conserved P-loop contains a short α helix, a turn, and a random coil (Zhorov and Tikhonov, 2004). It dips into and then out of the membrane from the exterior side of the membrane, forming the ion conducting pathway across the membrane, and includes the amino acids that form an ion selective filter (Ward et al., 2009). The quaternary structure of a P-loop cation conduction pathway of a P-loop channel is formed by four P-loops assembling into an “inverted teepee” structure across the membrane (Figure 2). The M1–P-loop–M2 structure of the P-loop polypeptide is present in bacterial cation channels, while the six TM polypeptide is characteristic of many cation channels in eukaryotes (Hua et al., 2003b).

Figure 1.

Representative structures of P-loop cation channels. Adapted from Hua et al., 2003a. (A) Representation of the core primary loop of a two transmembrane/one pore P-loop channel. (B) A six transmembrane/one pore P-loop plant CNGC channel polypeptide. P designates the P-loop of the channel. (C) A representation of the secondary structure of an animal Ca2+ channel, containing four repeats of the six transmembrane/one pore structure in one large polypeptide.

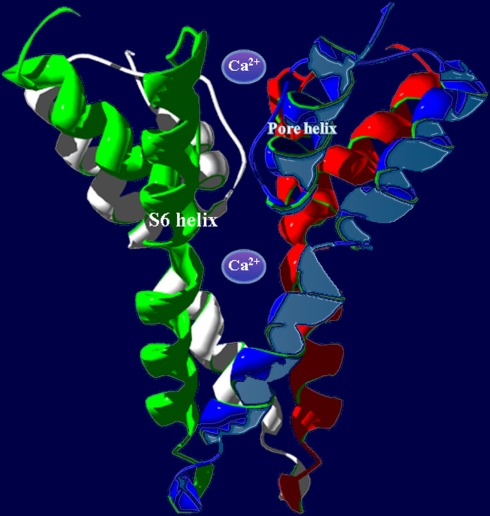

Figure 2.

In animals, P-loop cation conduction pathways are known to be formed from four P-loops in an “inverted teepee” structure stretching across the membrane. Shown is an example of a pore structure generated from the corresponding regions of four A. thaliana CNGC2 polypeptides illustrating the “inverted teepee” conformation formed by four P-loops arranged symmetrically. Ca2+ ions are shown moving through the conduction pathway of the channel.

The super families of voltage-gated and ligand-gated channels share this six TM P-loop structure (Mäser et al., 2001). The fact that many channel families share this primary polypeptide structure with common folds is consistent with the concept that the number of ion channel proteins with specific functional properties is substantially larger than the possible folding patterns that could accommodate the generation of an ion-conducting pathway across membranes (Zhorov and Tikhonov, 2004). In animals, voltage-gated Na+, K+, and Ca2+-selective channels evolved from the rudimentary progenitor P-loop channels. In higher animals, voltage-gated Na+- and Ca2+-selective channels are formed by one large polypeptide that has four repeat sections; each section contains the six TM P-loop structure (Zhorov and Tikhonov, 2004). The secondary structure of a polypeptide that forms animal Ca2+-selective ion channels is shown in Figure 1C. Genes encoding canonical “four repeat P-loop” Ca2+-selective channels present in animal genomes are absent in plants.

Potassium channels are formed by four separate polypeptides. In each case, four P-loops are aligned to form the ion-conducting pathway (Zheng and Zagotta, 2004). Figure 2 portrays the ion-conducting pathway formed by four P-loops of four different polypeptides (in different colors); also shown is the S6 TM domain of each of the four polypeptides. The configuration of voltage-gated channels is affected by the membrane potential (Em) such that the pore is physically occluded and therefore closed at some membrane potentials (blocking conductance), and open at other potentials. Evenly spaced, positively charged amino acids in the S4 domain of P-loop channels (represented as a “+” symbol on S4 in Figure 1B) act as a voltage sensor and provide a mechanism for the channel to sense and then respond to the Em by altering the gating of the pore (Hua et al., 2003b). Ligand-gated ion channels, including CNGCs, are also represented in the six TM P-loop superfamily.

Conductance through the pore of channels can also be gated by the binding of ligands to the N- and C-terminal extensions into the cytosol (Biel, 2009). Animal CNGCs are gated allosterically by calmodulin (CaM) and cyclic nucleotides (cAMP and/or cGMP). CaM (in the presence of cytosolic Ca2+) binds to a CaM binding domain (CaMBD) of animal CNGCs at the N-terminus; CaM binding closes the CNGC channel thus preventing ion conductance. Cyclic nucleotides can bind at the C-terminus of both plant and animal CNGCs. CNMP binding to the CNBD of CNGC polypeptides activates the channel, opening it and thereby enabling cation conductance. The aforementioned S4 loop voltage sensor of voltage-gated channels is also present in plant CNGCs.

Plant CNGCs have been demonstrated to function as channels with hyperpolarization-activated (i.e., inwardly rectified), voltage-dependent conductance (Hua et al., 2003b). There are two classes of animal channels whose conductance is regulated by cyclic nucleotides (Biel, 2009). Animal CNGCs are directly activated upon binding of cyclic nucleotides and their open probability does not change at varying Em. Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (HCNs) conduct ions (i.e., are open) at hyperpolarizing Em, and binding of cyclic nucleotides increases the percentage of open channels at a given hyperpolarizing Em. Thus, conductance of these channels changes at varying Em as well as in response to changes in the level of cyclic nucleotides in the cytosol. In plants CNGCs may be incorrectly classified as solely “ligand-gated” channels without response to voltage when in fact they may function like animal HCNs.

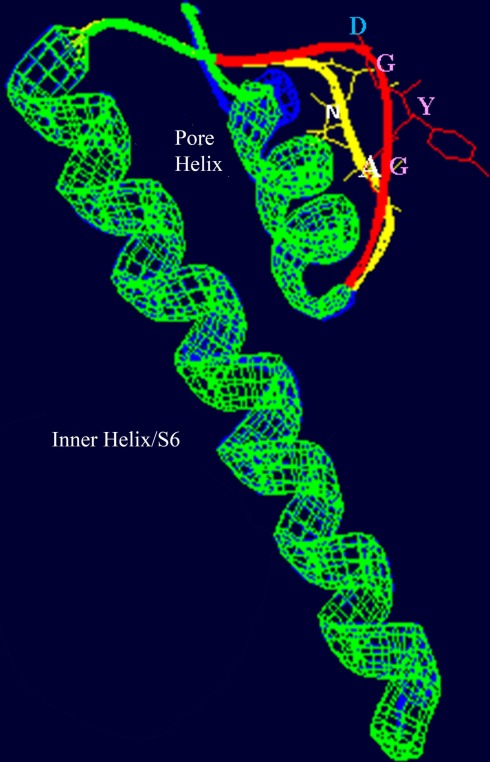

As indicated above, the quaternary structure of a member of the P-loop channel family is dependent on the assembly of four gene products in some cases (e.g., in animal and plant K+-selective voltage-gated channels) where only one P-loop “cassette” is encoded by the gene (i.e. S1–S6 with the P-loop between S5 and S6). It is therefore conceivable that plant CNGC channel complexes are formed by the assembly of four polypeptides, with each polypeptide corresponding to a structure similar to that shown in Figure 1B. Threading regions (S6 and pore loop, an example is shown in Figure 3 below) of plant CNGC coding sequences through the crystal structure of a quaternary P-loop channel indicates that the plant CNGC polypeptide may be capable of forming the tetrameric structure common to P-loop channels (Hua et al., 2003b). However, this model has not been verified experimentally. It should be noted that functional animal CNGC channel proteins are in all cases generated from such a tetrameric assembly of P-loop cassette polypeptides (Zheng and Zagotta, 2004) and that plant and animal CNGC polypeptides share a similar general S1–S6 topography. Thus, the aforementioned conjecture about the tetrameric structure of plant CNGCs is entirely consistent with the general concept of ion channel assembly and function.

Figure 3.

Superimposed images (redrawn from Leng et al., 2002) of the S6 helix and pore domains of the plant (A. thaliana) CNGC2 sequence and the bacterial (Streptomyces lividans) K+-selective channel KcsA (Doyle et al., 1998; PDB record 1BL8A). Threading of the A. thaliana CNGC2 S6 transmembrane helix and pore region through the KcsA structure identifies the residues “AND” as in the ion conducting pathway where the residues “GYG” (shown in pink) that form the ion selectivity filter of a K+-selective channel are positioned. This suggests that plant CNGCs may have a mechanism for cation conductance that is conserved in P-loop channels. In plants, four separate CNGC peptides are presumed to form a tetrameric structure that shares the “inverted teepee” quaternary structure of animal P-loop channels.

The amino acids that line the pore selectivity filter of P-loop channels determine the relative conductance for Na+, K+, and Ca2+. This region of a plant CNGC (A. thaliana, CNGC2, isoform 2) is shown superimposed over the corresponding region of a K+-selective channel in Figure 3. The triplet “GYG” forms the selectivity filter of the K+ channel. The corresponding residues in CNGC2 are “AND,” with the negatively charged aspartic acid (D) residue positioned at the outer mouth of the pore. No other plant CNGC has a selectivity filter with an acidic D or glutamic acid (E) at this position in the pore. Animal voltage-gated Ca2+-selective channels have an “EEEE” ring at the extracellular end of the ion conducting pathway formed by the corresponding residues in each of the four P-loop repeats that form the functional channel. This E ring of Ca2+ channels has been experimentally verified to coordinate divalent Ca2+ ions as they enter the pore; and cause Ca2+ selectivity in animal channels (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2011). The selectivity filter of plant CNGCs does not appear to be conserved among isoforms within this protein family, and is different from the conserved pore of animal CNGCs. However, some plant CNGCs have an acidic E two residues away from the D of CNGC2 (the D residue can be seen close to the outer mouth of the channel pore in Figure 3). The D in CNGC2, or alternatively the two E residues close to the outer mouth of the pore may conceivably provide a basis for Ca2+ conductance by some of the plant CNGCs. In A. thaliana, CNGCs 2, 4, 11, 12, 5, 6, and 9 have the E at the outer mouth of the pore and CNGCs 1, 2, 10, 11, 12, and 18 have been experimentally demonstrated (either directly or indirectly) to be involved in Ca2+ conductance (Leng et al., 1999; Ali et al., 2006; Frietsch et al., 2007; Urquhart et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2010). The speculative functional assignment of this acidic residue of the plant CNGC selectivity filter awaits further experimental confirmation.

A defining structural aspect of plant CNGCs is their CNBD, which is unique for a number of reasons. The presence of CNGC coding sequences with CNBDs in animal and plant is intriguing from an evolutionary perspective. Unicellular fungi lack channels with such CNBDs (Talke et al., 2003). Considering that plants branched from animal progenitors on the evolutionary tree before the animal–fungus division, CNGCs might have evolved independently in these two lineages. Alternatively, fungi might have lost CNGC channel genes. Some aspects of the structural features of the plant CNBD correspond to that of their bacterial and animal cyclic-nucleotide-binding analogs. The CNBD of plant CNGCs overlaps with a CaMBD near the C-terminus, and CaM (in the presence of Ca2+) prevents cNMP activation of plant CNGCs (Hua et al., 2003a). However there is no corresponding CaMBD in bacterial CNGC sequences (Cukkemane et al., 2011). In animals the functional CaMBD is located distal of the CNBD, near the N-terminus (Ungerer et al., 2011). As mentioned above, CaM binds to and regulates the conductance of animal CNGCs and this is also the case in plant CNGCs. However, in plant CNGCs, the amino acids that form the CaM binding domain overlap with the region of the polypeptide that forms the CNBD (Figure 1B). The predicted three-dimensional structure of a plant CNGC CNBD (Figure 4A) has been generated by threading this portion of the polypeptide through the crystal structure of a bovine CNBD shown in Figure 4B (Hua et al., 2003a). Similar structures can be found in the literature (Chikayama et al., 2004; Bridges et al., 2005; Kaplan et al., 2007). The Protein Data Bank contains a solved structure for the calmodulin binding domain (CaMBD) of a small conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel (SK2) in Rattus norvegicus (Wissmann et al., 2002; PDB record 1KKD). Threading the plant CNGC CaMBD sequences through the rat CaMBD structure may shed light on the possible convergent evolution of animal and plant CaMBDs present in ion channels.

Figure 4.

Predicted three-dimensional structures of the plant CNGC CNBD. (A) A proposed three-dimensional structure of the A. thaliana CNGC2 CNBD generated by threading the sequence through the structure of the cAMP-binding domain of PDB record 1RGS, bovine cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (RIα; Su et al., 1995). (B) Three-dimensional structure of the CNBD of RIα that was used to create the model of the CNGC2 CNBD. The CNBD structures of CNGC2 and RIα share an N-terminal α-helix (αA) and a β-barrel (depicted as ribbons with arrows denoting antiparallel strands) that together bind the cNMP ligand. Republished from Hua et al. (2003a). (C) The tertiary structure of the A. thaliana CNGC6 CNBD (Chikayama et al., 2004; PDB record 1WGP). Amino acid residues comprising the hinge domain are highlighted in yellow; α-helices are depicted as purple cylinders. The β-barrel is shown as straight antiparallel purple ribbons. Two cGMP molecules are shown with the structure, one in the pocket formed between an αA helix and the β-barrel, and a second cGMP molecule (not bound) is depicted at the α-C helix adjacent to the hinge domain.

It should be noted that plants contain two known domains, GAF and CNBD, which bind cyclic nucleotides. The GAF domain evolved billions of years ago and was first identified as a structural component of some cGMP phosphodiesterases and some light-sensing proteins in bacteria, yeast, humans, A. thaliana, and several species of cyanobacteria (Aravind and Ponting, 1997). Besides cAMP and cGMP, GAF domains can bind a number of other small molecules and are not specific to cNMPs (Bridges et al., 2005). The CNBD found in all plant CNGCs is also present in members of three plant K+-selective channel families; the “Shaker-like” (so named for the shaking phenotype of some animals with null mutations) KAT and AKT channel families, and the outwardly conducting channels SKOR and GORK. However, these K+-selective channels are affected by cyclic nucleotides in a very different manner than CNGCs. The voltage threshold for activation is shifted to more negative potentials in the presence of cGMP (experimentally verified for isoforms of the KAT and AKT families (Hoshi, 1995; Gaymard et al., 1996); the outward rectifiers have not been studied). This effectively means that cNMP elevation in the cytosol would reduce conductance through plant K+ channels that have CNBDs. Electrophysiological analysis of plant CNGCs has shown that the same elevation of cNMP activates the channel thereby increasing conductance (Leng et al., 1999, 2002; Lemtiri-Chlieh and Berkowitz, 2004; Ali et al., 2007).

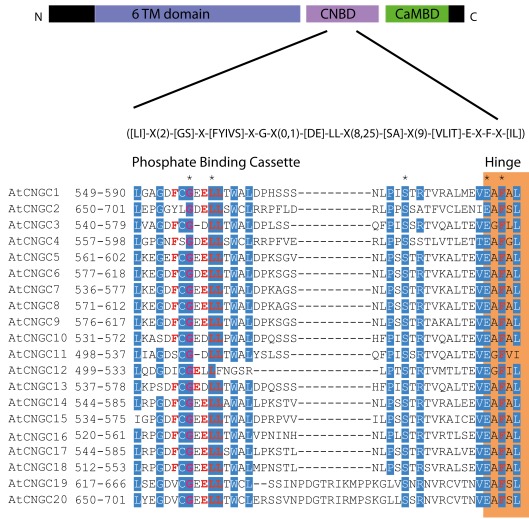

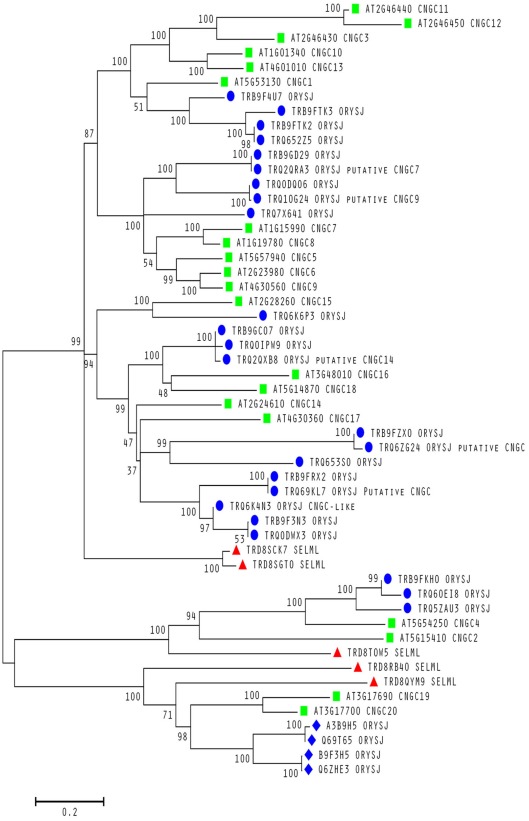

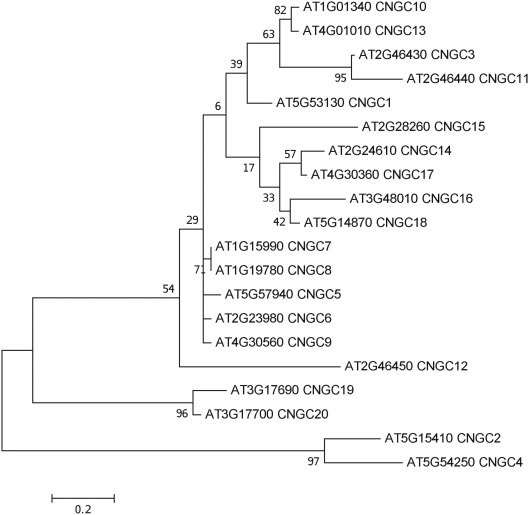

To date, no CNGC-specific motifs have been reported, however, Jackson et al. (2007) aligned different animal CNGCs, and in particular their PBC and hinge regions from which the following consensus motif can be derived: FGE-[IT]-[CIA]-LL-X(3,4)-[RK]-R-X-A-SV-X(11)-[SH]-[VRA]-[FY]-[HNQ]-X-[LV]-[LA] (the animal CNGC hinge sequence spans from the conserved serine (S) to the C-terminus of the motif). We noted that such a motif does not occur in plants but hypothesized that some of the functionally critical residues might be conserved. We therefore aligned A. thaliana CNGCs and identified putative PBCs and hinges. Within the putative PBCs we identified a conserved phenylalanine (F), a stabilizing glycine (G) and an acidic residue (either D or E) followed by two aliphatic leucines (L). We also observed that the putative hinge also contains an E, F, and one aliphatic residue much like in the animal CNGCs. The plant CNGC hinge occurs in between the CNBD and CaMBD regions (Figure 4C). We subsequently built a stringent motif ([LI]-X(2)-[GS]-X-[FYIVS]-X-G-X(0,1)-[DE]-LL-X(8,25)-[SA]-X(9)-[VLIT]-E-X-F-X-[IL]) that recognizes 20 A. thaliana CNGC proteins and no other sequences in A. thaliana. This subsequence includes the hinge domain and PBC (Figure 5). This conserved sequence differs from the animal CNBD; it occurs in between the CNBD and CaMBD while in animals the hinge occurs within the CNBD itself. Additionally it lacks, for example, the conserved proline (P) that was shown to affect gating in animal CNGCs (Jackson et al., 2007). Possible functional similarities may derive from the correspondence between the F in the center of the hinge in A. thaliana CNGCs and the F/Y in a bovine and a catfish CNGC (Young and Krougliak, 2004). The animal PBC region differs from the A. thaliana PBC conserved residues as well (Young and Krougliak, 2004). A scan of UniProt (Swiss-Prot/TrEMBL, The UniProt Consortium, 2012) including splice variants and excluding fragments using the ScanProSite tool2 (Sigrist et al., 2010) further revealed that the motif is restricted to land plants. Notably, the three predicted algal CNGC sequences from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Verret et al., 2010) lacked the motif. CNGC-related sequences matched against the 20 A. thaliana CNGCs using BLASTP (E-value <0.01) in UniProt for rice (Oryza sativa var. japonica) and the pin-cushion spikemoss (Selaginella moellendorffii) were then extracted, along with all hits for A. thaliana. Duplicates were removed and the remaining 53 sequences checked for the motif, before being used to construct a cladogram (Figure 6). The genes included in this cladogram are listed in Table A1 in Appendix. In this cladogram it can be seen that the majority of the rice and A. thaliana sequences tend to group together intraspecifically, suggesting numerous gene duplication events. The sequences across all three species partition into two clusters: a larger, more diverse cluster containing the bulk of the CNGC gene family, and a smaller cluster containing CNGC2, 4, 19, and 20. Of particular interest is that the only sequences to contain a conserved alanine (A) in place of the more frequent S in the motif are all from rice (denoted by blue diamonds) and all group together closely with CNGC19 and 20. The cladogram shown in Figure 7 is based upon only the conserved CNGC-specific motif. This phylogeny has striking congruence to previously published cladograms generated from aligning the full-length A. thaliana CNGC gene sequences (Mäser et al., 2001; Talke et al., 2003; Ward et al., 2009), as well as alignments of the pore domain amino acid sequences and the CNDB domain amino acid sequences (Kaplan et al., 2007). This supports the idea that the motif is informative for identifying and comparing putative CNGCs in other plants. Figure 7 also suggests that mutations in the motif have occurred concurrently with the branching of the CNGC gene family.

Figure 5.

The A. thaliana CNGC-specific motif spans the putative PBC and the hinge within the CNBD of the 20 CNGCs. The diagram at the top portrays three regions of plant CNGCs: the six transmembrane domains (TM), a CNBD containing a PBC and the hinge which presumably make direct contact with the cyclic nucleotide, and a calmodulin binding domain (CaMBD) toward the C-terminus. The CNGC-specific amino acid motif is shown below the cartoon. In the square brackets “[]” are the amino acids allowed in this position of the motif, “X” represents any amino acid and the round brackets “()” indicate the number of amino acids. The red amino acids in the PBC and the hinge are conserved in both animal and plant CNBDs based on comparison with Jackson et al. (2007). Below the CNGC-specific motif is an alignment of the motif regions of the 20 A. thaliana CNGCs. For each of the A. thaliana CNGCs, the residues at the N- and C-termini are indicated to the left of the motif. The green shaded box demarcates the putative PBC region of the CNBDs (corresponding to the animal CNBD PBC). The orange shaded box marks the presumed hinge region. Residues in white highlighted in blue indicate >90% identity among the 20 A. thaliana CNGCs (in this case “N” is counted as a dissimilarity) indicating a high level of conservation. A “*” above the alignment marks a position with 100% conservation between the A. thaliana sequences shown. Residues in red denote conservation with the animal CNBD alignment generated by Jackson et al. (2007). Note, there is experimental evidence identifying the residues which interact with cyclic nucleotides in animal CNBDs according to Jackson et al., but there is no empirical confirmation of which residues in plant CNBDs bind cyclic nucleotides. The alignment of the A. thaliana CNGC-specific motif was generated by the MEGA5 program and ClustalW (Saitou and Nei, 1987).

Figure 6.

Evolutionary relationships within a conserved motif in plant CNGCs. Molecular phylogenetic analysis using the Maximum Likelihood method for 53 cyclic nucleotide-gated channel (CNGC) amino acid sequences from A. thaliana (green squares), S. moellendorffii (red triangles) and O. sativa var. japonica (blue circles and diamonds). All sequences contain a conserved S between the two motif subsequences except for the rice sequences labeled with a diamond. All A. thaliana sequences are from confirmed CNGCs while the remaining sequences from the other two species are from uncharacterized proteins unless stated otherwise as putative CNGCs. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. The sequences used to create the tree were obtained using BLASTP (Camacho et al., 2009) with an E-value <0.01 against the UniProt Knowledgebase (The UniProt Consortium, 2012) for Viridiplantae from the European Bioinformatics Institute website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/sss/ncbiblast/) for all 20 annotated CNGCs from A. thaliana. All sequences from S. moellendorffii, O. sativa var. japonica, and A. thaliana were then extracted from the hits with exact duplicates (same identifiers, same sequence and different identifiers, same sequence) as well as annotated fragments being removed. The remaining sequences containing the motif ([LI]-X(2)-[GS]-X-[FYIVS]-X-G-X(0,1)-[DE]-LL-X(8,25)-[SA]-X(9)-[VLIT]-E-X-F-X-[IL]) were then aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) and inspected for isoforms (near 100% identity) and unannotated fragments. The bootstrap consensus tree was generated using the JTT matrix-based model with discrete gamma distribution (five categories (+ G, parameter = 1.0524); Jones et al., 1992) by MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2011) from 1000 bootstraps (Felsenstein, 1985). It is drawn to scale with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site and all ambiguous positions removed for each sequence pair. It is based on 1082 positions in the final data set. Branches corresponding to less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed and the percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together are shown next to the branches. The BioNJ method with the MCL distance matrix was used to generate the initial trees except where the common sites were less than 100 or a quarter of the total sites, in which case, maximum parsimony was used.

Figure 7.

Molecular phylogenetic history of the CNGC-specific conserved motif ([LI]-X(2)-[GS]-X-[FYIVS]-X-G-X(0,1)-[DE]-LL-X(8,25)-[SA]-X(9)-[VLIT]-E-X-F-X-[IL]) in A. thaliana. The analysis used the Maximum Likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model with a discrete gamma distribution [five categories (+G, parameter = 1.0852); Jones et al., 1992] in MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2011) with 1000 bootstraps (Felsenstein, 1985). The initial heuristic trees were obtained automatically using the BioNJ method with MCL distance, unless the number of common sites was less than 100 or one quarter of the total number of sites, in which case the maximum parsimony method was used. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−771.1381) is shown, drawn to scale with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. All ambiguous positions were removed for each sequence pair with a total of 52 positions in the final dataset of 20 sequences.

Interestingly, the motif recognizes all currently annotated CNGCs in higher plants only and identifies new unannotated candidate CNGCs. Two CNGC isoforms in A. thaliana [Swiss-Prot: Q94AS9-2 (an isoform of CNGC4) and Q8GWD2-2 (an isoform of CNG12)] lack the motif. However, these sequences are not experimentally confirmed and are truncated. The few annotated CNGCs in other plants (e.g., barley and poplar) that lack the motif – even if we relax it by allowing one or several mismatches – may suggest that they are either misannotated, or fragments that show insufficient coverage and similarity to be confidently classified as CNGCs. Furthermore, the motif recognizes neither any non-plant sequences nor any algal sequences. We therefore contend that the motif may serve as a supporting method for identifying CNGCs in other land plant species.

Scanning the rice and pin-cushion spikemoss genomes with the ScanProsite tool yields putative CNGC homologs and uncharacterized proteins containing the motif (Figure 6). Since CNBDs are found in other proteins besides the CNGC ion channels in the A. thaliana proteome (as noted above, i.e., the K+-selective channels), it may be useful to develop motifs that can distinguish these sequences. Several recent publications predict the number of CNGCs present in the genomes of organisms ranging from brown and red algae to green algae and multicellular plants. For example, Ward et al. (2009) predict that no CNGCs exist in the green alga C. reinhardtii. In contrast, Verret et al. (2010) predict that C. reinhardtii has three CNGCs. These three sequences do not contain the land plant-specific CNGC motif. The fact that these authors disagree on the number of CNGCs attests to the need for alternative ways to assess the likelihood that a protein for which the primary sequence is known is likely to function as a CNGC. The motif we present here does not recognize any non-plant sequences or any algal sequences, and thus lends weight to the view that the C. reinhardtii proteins identified as putative CNGCs by Verret et al. (2010) may contain algal-specific CNGC motifs and we argue that higher plants may have evolved a specific cNMP-binding domain.

A functional motif-based means of recognizing CNGC proteins will also contribute to our understanding the evolutionary history of this gene family including the possible role of genome and gene duplication events (Seoighe and Gehring, 2004). Analyzing orthologous CNGCs in the new Whole Genome Shotgun sequence of Arabidopsis lyrata, a cress whose genome is approximately 50% larger than that of A. thaliana, is the next obvious step in learning more about the evolutionary effects of ion channel gene duplication and subsequent sub-functionalization and changing expression patterns. These phenomena have already been partly addressed (Mäser et al., 2001), and it was remarked that CNGC12 has a CaMBD that was the least conserved compared to the other CNGCs this group (Group I). CNGC12 was the last gene in a sequence of three syntenic CNGCs: CNGC3 and CNG11 precede it. CNGC12 is likely the least homologous indicating that gene duplication allowed the original function of the Group I gene CNGC3 to be maintained, easing selection pressure on the duplicate copies and perhaps allowing for sub-functionalization.

Concluding Remarks

The pore and CNBD sequences of the plant cyclic nucleotide-gated channels differ from the pore and CNBDs in other plant ion channel families. They are also different from the pore and CNBD regions of animal CNGCs. Phylogenies based on alignments of the pore, CNBD, or full-length CNGC sequences are similar, showing that the evolution of these functional domains preceded the expansion of plant CNGC genes that occurred after the split between green algae and higher plants, and that the split between dicots and monocots occurred after the advent of the higher plant CNGCs. A protein motif specific to plant CNGCs is located within the CNBD. An alignment of just this motif region from the CNGCs produces a cladogram that is almost identical to published phylogenies of the full-length sequences. This motif may therefore be used to refine tentative annotations and to find novel CNGCs in newly sequenced plant genomes. Whether this motif represents differences in the function or regulation of plant CNGCs has yet to be evaluated.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nadia Burger and Nathan Wojtyna for assistance in preparing images. This work is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation (Award 1146827).

Appendix

Table A1.

| Key | Database | Species | Accession | Description/Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1G01340 CNGC10 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT1G01340 | CNGC10 |

| AT1G15990 CNGC7 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT1G15990 | CNGC7 |

| AT1G19780 CNGC8 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT1G19780 | CNGC8 |

| AT2G23980 CNGC6 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT2G23980 | CNGC6 |

| AT2G24610 CNGC14 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT2G24610 | CNGC14 |

| AT2G28260 CNGC15 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT2G28260 | CNGC15 |

| AT2G46430 CNGC3 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT2G46430 | CNGC3 |

| AT2G46440 CNGC11 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT2G46440 | CNGC11 |

| AT2G46450 CNGC12 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT2G46450 | CNGC12 |

| AT3G17690 CNGC19 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT3G17690 | CNGC19 |

| AT3G17700 CNGC20 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT3G17700 | CNGC20 |

| AT3G48010 CNGC16 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT3G48010 | CNGC16 |

| AT4G01010 CNGC13 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT4G01010 | CNGC13 |

| AT4G30360 CNGC17 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT4G30360 | CNGC17 |

| AT4G30560 CNGC9 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT4G30560 | CNGC9 |

| AT5G14870 CNGC18 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT5G14870 | CNGC18 |

| AT5G15410 CNGC2 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT5G15410 | CNGC2 |

| AT5G53130 CNGC1 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT5G53130 | CNGC1 |

| AT5G54250 CNGC4 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT5G54250 | CNGC4 |

| AT5G57940 CNGC5 | TAIR | A. thaliana | AT5G57940 | CNGC5 |

| TRB9F3N3 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9F3N3_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9F4U7 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9F4U7_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9FKH0 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9FKH0_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9FRX2 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9FRX2_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9FTK2 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | TRB9FTK2_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9FTK3 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9FTK3_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9FZX0 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9FZX0_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9GC07 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9GC07_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRB9GD29 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9GD29_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRQ0DQ06 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q0DQ06_ORYSJ | Os03g0646300 protein (CNGC7-like) |

| TRQ0DWX3 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q0DWX3_ORYSJ | Os02g0789100 protein (CNGC17-like) |

| TRQ0IPW9 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q0IPW9_ORYSJ | Os12g0163000 protein (CNGC18-like) |

| TRQ10G24 ORYSJ putative CNGC9 | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q10G24_ORYSJ | Putative CNGC9 |

| TRQ2QRA3 ORYSJ putative CNGC7 | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q2QRA3_ORYSJ | Putative CNGC7 |

| TRQ2QXB8 ORYSJ putative CNGC14 | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q2QXB8_ORYSJ | Putative CNGC14 |

| TRQ5ZAU3 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q5ZAU3_ORYSJ | Os01g0782700 protein (CNGC4-like) |

| TRQ60EI8 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q60EI8_ORYSJ | Os05g0502000 protein (CNGC4-like) |

| TRQ652Z5 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q652Z5_ORYSJ | Os06g0527100 protein (CNGC1-like) |

| TRQ653S0 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q653S0_ORYSJ | Os09g0558300 protein (ATCNGC14-like) |

| TRQ69KL7 ORYSJ Putative CNGC | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q69KL7_ORYSJ | Putative CNGC |

| TRQ6K4N3 ORYSJ CNGC-like | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q6K4N3_ORYSJ | CNGC-like |

| TRQ6K6P3 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q6K6P3_ORYSJ | Os02g0627700 protein (CNGC15-like) |

| TRQ6ZG24 ORYSJ putative CNGC | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q6ZG24_ORYSJ | putative CNGC |

| TRQ7X641 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q7X641_ORYSJ | OSJNBa0033G05.7 protein (CNGC-like) |

| TRA3B9H5 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | A3B9H5_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRQ69T65 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q69T65_ORYSJ | Putative cyclic nucleotide-regulated ion channel |

| TRB9F3H5 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | B9F3H5_ORYSJ | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRQ6ZHE3 ORYSJ | UniProt | O. sativa var. japonica | Q6ZHE3_ORYSJ | Putative cyclic nucleotide-binding transporter 1 |

| TRD8QYM9 SELML | UniProt | S. moellendorffii | D8QYM9_SELML | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRD8RB40 SELML | UniProt | S. moellendorffii | D8RB40_SELML | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRD8SCK7 SELML | UniProt | S. moellendorffii | D8SCK7_SELML | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRD8SGT0 SELML | UniProt | S. moellendorffii | D8SGT0_SELML | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| TRD8T0W5 SELML | UniProt | S. moellendorffii | D8T0W5_SELML | Putative uncharacterized protein |

- Swarbreck D., Wilks C., Lamesch P., Berardini T. Z., Garcia-Hernandez M., Foerster H., Li D., Meyer T., Muller R., Ploetz L., Radenbaugh A., Singh S., Swing V., Tissier C., Zhang P., Huala E. (2008). The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): gene structure and function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D1009–D1014 10.1093/nar/gkm965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

References

- Abdel-Hamid H., Chin K., Moeder W., Yoshioka K. (2011). High throughput chemical screening supports the involvement of Ca2+ in cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel-mediated programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 11, 1817–1819 10.4161/psb.6.11.17502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam A., Shi N., Jiang Y. (2007). Structural insight into Ca2+ specificity in tetrameric cation channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15334–15339 10.1073/pnas.0705599104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R., Ma W., Lemtiri-Chlieh F., Tsaltas D., Leng Q., von Bodman S., Berkowitz G. A. (2007). Death don’t have no mercy and neither does calcium: Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide gated channel 2 and innate immunity. Plant Cell 19, 1081–1095 10.1105/tpc.106.045096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R., Zielinski R., Berkowitz G. A. (2006). Expression of plant cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels in yeast. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 125–138 10.1093/jxb/erj012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L., Ponting C. P. (1997). The GAF domain: an evolutionary link between diverse phototransducing proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22, 458–459 10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01148-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M. (2009). Cyclic nucleotide-regulated cation channels. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9017–9021 10.1074/jbc.R800075200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges D., Fraser M. E., Moorhead G. B. G. (2005). Cyclic nucleotide binding proteins in the Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 6–18 10.1186/1471-2105-6-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., Madden T. L. (2009). BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421–430 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikayama E., Nameki N., Kigawa T., Koshiba S., Inoue M., Tomizawa T., Kobayashi N., Yokoyama S. (2004). Solution structure of the cNMP-binding domain from Arabidopsis thaliana cyclic nucleotide-regulated ion channel. RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative. PDB ID:1WGP. 10.2210/pdb1wgp/pdb [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cukkemane A., Seifert R., Kaupp U. B. (2011). Cooperative and uncooperative cyclic-nucleotide-gated ion channels. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 55–64 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle D. A., Morais Cabral J., Pfuetzner R. A., Kuo A., Gulbis J. M., Cohen S. L., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (1998). The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science 280, 69–77 10.1126/science.280.5360.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 113–132 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frietsch S., Wang Y. F., Sladek C., Poulsen L. R., Romanowsky S. M., Schroeder J. I., Harper J. F. (2007). A cyclic nucleotide-gated channel is essential for polarized tip growth of pollen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14531–14536 10.1073/pnas.0701781104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaymard F., Cerutti M., Horeau C., Lemaillet G., Urbach S., Ravallec M., Devauchelle G., Sentenac H., Thibaud J. B. (1996). The baculovirus/insect cell system as an alternative to Xenopus oocytes. First characterization of the AKT1 K+ channel from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22863–22870 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K. M., Babourina O., Christopher D. A., Borsic T., Rengel Z. (2010). The cyclic nucleotide-gated channel AtCNGC10 transports Ca2+ and Mg2+ in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Plant 139, 303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T. (1995). Regulation of voltage dependence of the KAT1 channel by intracellular factors. J. Gen. Physiol. 105, 309–328 10.1085/jgp.105.3.309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua B.-G., Mercier R. W., Zielinski R. E., Berkowitz G. A. (2003a). Functional interaction of calmodulin with a plant cyclic nucleotide gated cation channel. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 41, 945–954 10.1016/j.plaphy.2003.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hua B.-G., Mercier R. W., Leng Q., Berkowitz G. A. (2003b). Plants do it differently: a new basis for potassium/sodium selectivity in the pore of an ion channel. Plant Physiol. 132, 1353–1361 10.1104/pp.103.020560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson H. A., Marshall C. R., Accili E. A. (2007). Evolution and structural diversification of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel genes. Physiol. Genomics 29, 231–245 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00142.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. T., Taylor W. R., Thornton J. M. (1992). The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8, 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan B., Sherman T., Fromm H. (2007). Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in plants. FEBS Lett. 581, 2237–2246 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M. M., Saimi Y., Kung C., Choe S. (2007). Patch clamp and phenotypic analyses of a prokaryotic cyclic nucleotide-gated K+ channel using Escherichia coli as a host. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24294–24301 10.1074/jbc.M703618200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemtiri-Chlieh F., Berkowitz G. A. (2004). Cyclic adenosine monophosphate regulates calcium channels in the plasma membrane of Arabidopsis leaf guard and mesophyll cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35306–35312 10.1074/jbc.M400311200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng Q., Mercier R. W., Hua B.-G., Fromm H., Berkowitz G. A. (2002). Electrophysiological analysis of cloned cyclic nucleotide gated ion channels. Plant Physiol. 128, 400–410 10.1104/pp.010832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng Q., Mercier R. W., Yao W. Z., Berkowitz G. A. (1999). Cloning and first functional characterization of a plant cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Plant Physiol. 121, 753–761 10.1104/pp.121.3.753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Yoshioka K., Gehring C. A., Berkowitz G. A. (2010). “The function of cyclic nucleotide gated channels in biotic stress,” in Ion Channels and Plant Stress Responses, eds Demidchik V., Maathuis F. J. M. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag; ), 159–174 [Google Scholar]

- Mäser P., Thomine S., Schroeder J. I., Ward J. M., Hirschi K., Sze H., Talke I. N., Amtmann A., Maathuis F. J., Sanders D., Harper J. F., Tchieu J., Gribskov M., Persans M. W., Salt D. E., Kim S. A., Guerinot M. L. (2001). Phylogenetic relationships within cation transporter families of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 126, 1646–1667 10.1104/pp.126.4.1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimigean C. M., Shane T., Miller C. (2004). A cyclic nucleotide modulated prokaryotic k+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 124, 203–210 10.1085/jgp.200409133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M. (1987). The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoighe C., Gehring C. (2004). Genome duplication led to highly selective expansion of the Arabidopsis thaliana proteome. Trends Genet. 20, 461–464 10.1016/j.tig.2004.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist C. J. A., Cerutti L., de Castro E., Langendijk-Genevaux P. S., Bulliard V., Bairoch A., Hulo N. (2010). PROSITE, a protein domain database for functional characterization and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 161–166 10.1093/nar/gkp885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Dostmann W. R., Herberg F. W., Durick K., Xuong N. H., Ten Eyck L., Taylor S. S., Varughese K. I. (1995). Regulatory subunit of protein kinase a: structure of deletion mutant with cAMP binding domains. Science 269, 807–813 10.1126/science.7638597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talke I. N., Blaudez D., Maathuis F. J. M., Sanders D. (2003). CNGCs: prime targets of plant cyclic nucleotide signalling? Trends Plant Sci. 8, 286–293 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00099-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium. (2012). Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D71–D75 10.1093/nar/gks060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S. (2011). Possible roles of exceptionally conserved residues around the selectivity filters of sodium and calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2998–3006 10.1074/jbc.M110.175406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerer N., Mücke N., Broecker J., Keller S., Frings S., Möhrlen F. (2011). Distinct binding properties distinguish LQ-type calmodulin-binding domains in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Biochem. 50, 3221–3228 10.1021/bi200115m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart W., Gunawardena A. H., Moeder W., Ali R., Berkowitz G. A., Yoshioka K. (2007). The chimeric cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel ATCNGC11/12 constitutively induces programmed cell death in a Ca2+ dependent manner. Plant Mol. Biol. 65, 747–761 10.1007/s11103-007-9239-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verret F., Wheeler G., Taylor A. R., Farnham G., Brownlee C. (2010). Calcium channels in photosynthetic eukaryotes: implications for evolution of calcium-based signalling. New Phytol. 187, 23–43 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. M., Mäser P., Schroeder J. I. (2009). Plant ion channels: gene families, physiology, and functional genomics analyses. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 59–82 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissmann R., Bildl W., Neumann H., Rivard A. F., Klöcker N., Weitz D., Schulte U., Adelman J. P., Bentrop D., Fakler B. (2002). A helical region in the C terminus of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels controls assembly with apo-calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4558–4564 10.1074/jbc.M109240200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young E. C., Krougliak N. (2004). Distinct structural determinants of efficacy and sensitivity in the ligand-binding domain of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3553–3562 10.1074/jbc.M311814200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Zagotta W. N. (2004). Stoichiometry and assembly of olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron 42, 411–421 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00253-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhorov B. S., Tikhonov D. B. (2004). Potassium, sodium, calcium and glutamate-gated channels: pore architecture and ligand action. J. Neurochem. 88, 782–799 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]