Abstract

Hibernating mammals have developed many physiological adaptations to extreme environments. During hibernation, 13-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus) must suppress hemostasis to survive prolonged body temperatures of 4–8°C and 3–5 heartbeats per minute without forming lethal clots. Upon arousal in the spring, these ground squirrels must be able to quickly restore normal clotting activity to avoid bleeding. Here we show that ground squirrel platelets stored in vivo at 4–8°C were released back into the blood within 2 h of arousal in the spring with a body temperature of 37°C but were not rapidly cleared from circulation. These released platelets were capable of forming stable clots and remained in circulation for at least 2 days before newly synthesized platelets were detected. Transfusion of autologous platelets stored at 4°C or 37°C showed the same clearance rates in ground squirrels, whereas rat platelets stored in the cold had a 140-fold increase in clearance rate. Our results demonstrate that ground squirrel platelets appear to be resistant to the platelet cold storage lesions observed in other mammals, allowing prolonged storage in cold stasis and preventing rapid clearance upon spring arousal. Elucidating these adaptations could lead to the development of methods to store human platelets in the cold, extending their shelf life.

Keywords: transfusion, megakaryocyte, thromboelastograph, microtubule, hypothermia

in 2006, over 4 million units of platelets were processed for transfusions in the United States, of which 15% expired before they could be used (23). Because of cold-induced platelet storage lesions (18, 20), platelets must stored at 22°C with only a 5-day shelf life to avoid bacterial contamination (7). Human, baboon, and mouse platelets that are cooled even briefly to 4°C and then transfused are rapidly cleared, negating any benefit of storage in the cold (2, 4, 10, 21). Two potential mechanisms of this clearance involve a clustering of von Willebrand factor (vWF) receptors (GPIbα-V-IX complex) on the surface of the platelets, followed by clearance through binding of platelet GPIbα to complement type 3 receptors (CR3) on Kupffer cells (hepatic macrophages) (8) or clearance by lectin receptors on hepatocytes (14, 15). Many other cold-induced structural and functional changes occur in human platelets, leading to increased aggregation and degranulation upon warming (22). Cells from organisms that undergo cold desiccating conditions often infuse their cells with cryoprotectants such as the sugar trehalose (6). Human platelets infused with trehalose, freeze dried and rehydrated, retained some function. However, the authors note that proper functioning of these chemically modified platelets in hemostasis is questionable (25). Identifying a model organism that can store its platelets in the cold without developing platelet storage lesions would be very helpful in identifying mechanisms to allow human platelets to be stored in the cold.

To survive in extreme environments, hibernating mammals such as 13-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus), hereafter referred to as ground squirrels, have developed profound physiological adaptations. Hibernation consists of extended bouts of torpor lasting from days to weeks during which time body temperatures drop to 4–8°C and heart rates drop down to 3–5 beats/min. These periods of torpor are interrupted by short interbout arousals during which body temperatures return to 37°C for 12–24 h before entering the next phase of torpor. Ground squirrels are able to survive 5 mo of hibernation, with 10–20 cycles of torpor and interbout arousal without forming lethal clots (9, 13, 26). Ground squirrels are rodents about the size of rats, and have clotting times similar to those of rats and mice when in their normothermic nonhibernating state. However, during torpor their blood clotting times are prolonged by a 70% decrease in Factors VIII and IX and a 90% drop in platelet and leukocyte levels (9, 12). The thrombocytopenia is caused by an organizational change in the platelet's band of circumferential microtubules (MT), resulting in the formation of elongated rods that distort the shape of the platelet (13). These elongated platelets are then sequestered in the spleen of the torpid ground squirrel. Within 2 h of a return to a body temperature of 37°C, platelets are released back into circulation (12, 13), which suggests that the central MT rod bundle is lost upon warming. In this way, the ground squirrels can rapidly shift from a thrombocytopenic, anticoagulant state during torpor to a state typical of a normothermic rodent as their body temperature returns to 37°C.

The behavior of ground squirrel platelets is different from that of other mammalian platelets in two important aspects. First, during torpor platelets are sequestered by the spleen and released upon interbout or spring arousal. Second, the ground squirrel platelet levels return to normal once the animals are aroused from up to 6 mo at 4°C, whereas human or mouse platelets stored under these conditions would rapidly be cleared from circulation by the liver. In this study we show that the structural organization of MTs in ground squirrel platelets is reversible and temperature dependent. Strikingly, ground squirrel platelets appear to be resistant to cold-induced clearance in vivo and in vitro, and are still functional upon release back into the blood in the spring. Ground squirrels could thus serve as a valuable new animal model for the cold storage of platelets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Ground squirrels were born in captivity and housed at UW-L following protocols submitted to and approved by the institutional IACUC. Nonhibernating animals were housed individually in rat caging on a Wisconsin photo period. In the fall, when an animal's body temperature dropped to 25°C (ambient), animals were placed in 8“ × 8” plastic containers with bedding and moved into a 4°C hibernaculum. Animals were checked daily for arousal, and if they were alert for 2 consecutive days they were moved out of the hibernaculum. In March, 14 animals were manually aroused from hibernation. Blood was collected from the tail arteries of nonhibernating ground squirrels while under anesthesia with isoflurane (1.5–5%) in one-ninth volume of acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD). Organs were collected from hibernating (January–February) and nonhibernating (July–August) animals by exsanguination while under anesthesia and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Platelet isolation.

Ground squirrel and rat blood samples were obtained from anesthetized animals by arterial tail puncture using a 27-gauge needle. Whole blood was centrifuged at 200 g for 8 min, the supernatant and buffy coat were removed, and the supernatant was centrifuged again at 100 g for 6 min to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Prostaglandin E1 was added to the PRP at 6 μM to prevent platelet activation. Platelets were pelleted from PRP by centrifugation at 800 g for 5 min. The platelet pellet was then resuspended in Tyrode buffer (in mM: 12 NaHCO3, 138 NaCl, 5.5 glucose, 2.9 KCl, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4) before further analysis.

Microscopy.

For fluorescence microscopy, PRP was centrifuged onto polylysine-coated microscope slides at 2,100 g for 4 min in a Cytofuge2 (StatSpin, Norwood, MA). Attached platelets were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in (in mM): 50 PIPES, pH 6.9, 3 EGTA, 1 MgSO4, and 25 KCl for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. After being blocked in 1% BSA for 30 min, a 1:1,000 dilution of mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and a 1:200 dilution of Alexa488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) primary and secondary antibodies were used, respectively. Texas red phalloidin (1:200) was used to stain actin (Invitrogen). Confocal microscopy was performed using a Nikon CS-1 system on an Eclipse TE2000-U inverted microscope with a ×60, 1.4 numerical aperture Plan Apo oil objective at room temperature.

For bone marrow histology, femurs were collected from torpid and normothermic animals and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin followed by decalcification with DeltaCAL. The bone was removed, and the bone marrow was paraffin embedded. Sections of 4 μm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The numbers of megakaryocytes per squared millimeter were counted in 10 images taken of each bone marrow section, and MK sizes in squared micrometers were measured on the same images using Image J.

Cell quantification.

Blood cell counts were performed using a HemaVet HV950 (Drew Scientific, Waterbury, CT). To measure reticulated platelets, 25 μl whole citrated blood samples were fixed in 5 ml 1% paraformaldehyde, 0.05% EDTA in PBS overnight at 4°C. Reticulated platelets were quantified following incubation with and without RNase and RNA stained with thiazole orange (TO; ReticCount, Becton Dickinson) (16). Platelets were identified based on forward- and side-scatter characteristics, and reticulated platelets were identified based on high levels of TO staining. Nonspecific staining of platelet granules by TO was corrected for using the following equation: %RP = (non-RNase-treated TO+ plateletes − RNase-treated TO+ platelets)/total platelets.

Thromboelastography.

Blood was collected from ground squirrels that were not hibernating (normothermic), hibernating (torpid), and 2 h postarousal from hibernation using a syringe containing 0.109 M citrated anticoagulant from a vacutainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lake, NJ). Blood (340 μl) was mixed with 10 μl of APTT-XL reagent (Pacific Hemostasis, Middletown, VA) for 90 s and recalcified to 20 mM Ca2+ to initiate clotting. Clot strength and kinetics of formation were measured on a TEG 5000 thromboelastograph (Haemonetics, Niles, IL).

Platelet clearance in vivo.

Jugular catheters were surgically implanted in rats, and normothermic ground squirrels were anesthetized with 90 mg/kg ketamine and 9 mg/kg Zylazine by intraperitoneal injection. Ketofen (1 mg/kg) was given intraperitoneally for postoperative pain control. One-milliliter blood samples were collected in ACD after catheter placement, and PRP was isolated at 37°C and incubated for 1.5 h at either 4°C or 37°C. Platelets were labeled for 20 min with either 2 μM CellTracker-Green (CM-green) or 5 μM BODIPY 630/650 methyl bromide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The dyes used to label platelets at each temperature were randomized to avoid a labeling bias. The labeled PRPs were then mixed, diluted in 2 ml of 37°C Tyrode buffer, and pelleted at 800 g for 5 min. The labeled platelets (1–3 × 109) were resuspended in 500 μl of 37°C PBS and simultaneously reinjected, followed by a 200-μl sterile saline flush. A zero time point was collected 10 min posttransfusion, and subsequent samples were obtained at 0.5, 2, 8, 24, 48, and 72 h. The first 100 μl removed at each time point were discarded to remove any labeled platelets or heparin remaining in the catheter. Samples were immediately analyzed on a Becton Dickenson FACS Calibur flow cytometer, and 50,000 platelet events were collected. The percentage of labeled platelets at each time point normalized to the zero time point was calculated and the data fit to a biexponential decay curve using Sigma Plot.

Kupffer cells were isolated by in situ perfusion of the liver through the portal vein with HBSS containing 5 mM Ca2+, 5 mM Mg2+, and 0.05% Type IV collagenase. The liver was removed and incubated in 20 ml of collagenase solution for 1 h, the cells were dispersed through cheesecloth and centrifuged for 2 min at 50 g to pellet debris and then at 800 g for 10 min to pellet the cells. Hepatocytes were isolated on a preformed Percoll (Fisher, Waltham, MA) gradient of 20 ml of overlayering buffer (1.037 g/ml, 300 mosM percoll) and 15 ml bottom buffer (1.066 g/ml, 310 mosM Percoll). The sample was centrifuged for 15 min at 400 g, the upper 20 ml containing debris were removed, and the next 20 ml containing Kupffer cells were collected, pelleted, and resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI media containing 10% FBS. A 12-well plate received 1 × 106 cells/well, and macrophages were allowed to adhere in a CO2 chamber for 2 h, followed by being washed three times with warm RPMI. Platelets were incubated at 4°C or 37°C for 1.5 h and then labeled for 20 min with 1.8 μM CellTracker-Orange (CM-Orange) (Invitrogen), and 1 × 108 were added to each well and incubated with the macrophages for 30 min. Nonadherent platelets were removed by washing three times with HBSS, and macrophages were dislodged with 0.05% trypsin for 5 min (8). At least 500 macrophages per sample were then analyzed for fluorescence on a Becton Dickenson FACS Calibur flow cytometer. We tried 10 different antibodies against mouse platelet antigens and could not find one that cross reacted with squirrel platelets, so we cannot distinguish between platelets still bound to surface receptors and those that were phagocytosed.

RESULTS

Reversible temperature-induced changes in MT organization.

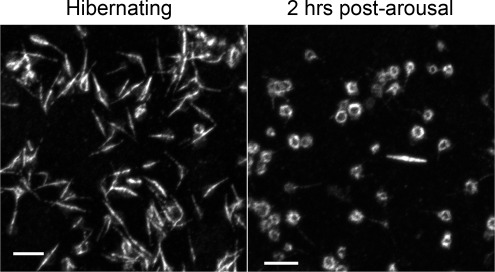

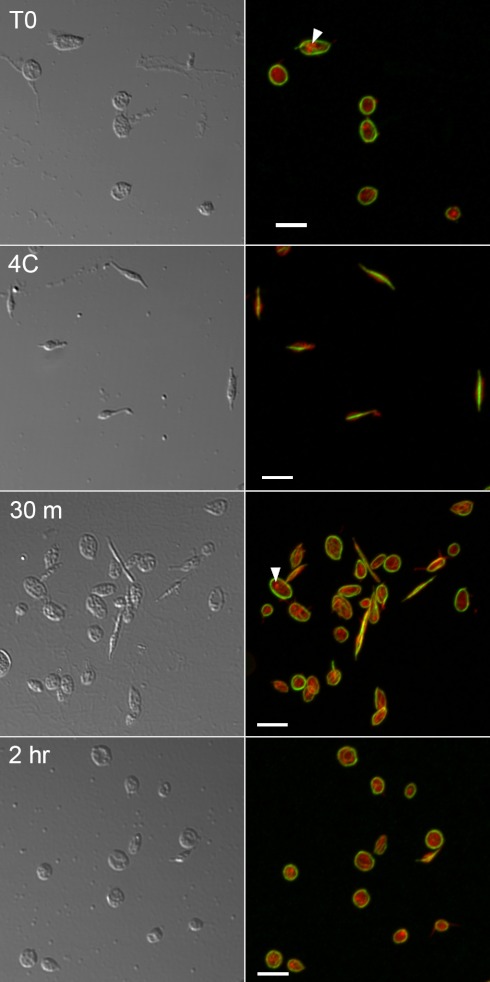

In this study ground squirrel body temperatures went from 9.8 ± 2.1°C to 36.4 ± 0.8°C within 2 h of arousal in the spring. Within this 2-h period the platelet MTs returned to their normothermic circumferential ring organization, coincident with their release back into circulation (Fig. 1). This reversible organizational change could be replicated in vitro with washed platelets through temperature manipulation alone (Fig. 2). Platelets isolated from nonhibernating ground squirrels possessed the typical circumferential ring of MTs, which converted to a central bundle forming an elongated rod after an hour at 4°C. Upon rewarming in vitro, MTs reorganized back into the circumferential ring, suggesting the MT organization is a temperature-sensitive property intrinsic to the ground squirrel platelets and not due to signals from other tissues that sequester the platelets.

Fig. 1.

Reversible platelet microtubule (MT) rod formation in vivo. Platelets were isolated from ground squirrel blood samples collected during hibernation and 2 h postarousal, centrifuged onto microscope slides, fixed, and immunostained for tubulin with a secondary antibody linked to Alexa-488. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Nikon CS-1 system on an Eclipse TE2000-U inverted microscope with a ×60, 1.4 NA Plan Apo oil objective at room temperature. Bars = 5 μm.

Fig. 2.

Reversible platelet MT rod formation in vitro. Platelets were isolated from a nonhibernating ground squirrel and immediately fixed onto slides (T0) or chilled at 4°C for 1 h and either fixed (4C) or rewarmed to 37°C for 30 min (30 m) or 2 h before being fixed and immunostained for tubulin and actin labeling with Texas red phalloidin. Circumferential microtubule rings (green, right) rapidly reform in many platelets after rewarming (30 m) and continue to recover over time (2 h). Accumulations of actin (red, right) around vesicles (arrowheads) indicate that platelets were not activated during the experiment. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Nikon CS-1 system on an Eclipse TE2000-U inverted microscope with a ×60, 1.4 NA Plan Apo oil objective at room temperature. Bars = 5 μm.

Rapid recovery of primary hemostasis after arousal from hibernation.

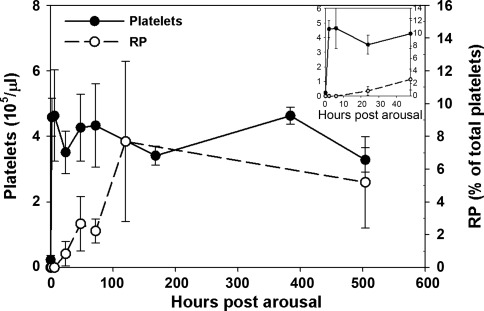

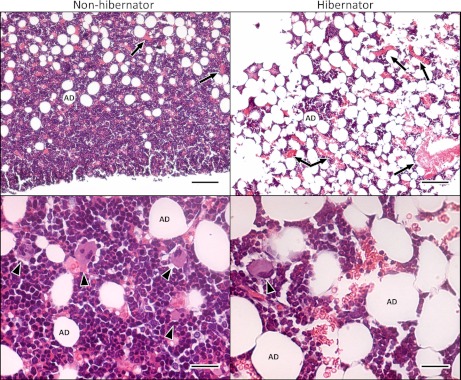

Upon arousal in the spring, ground squirrel platelet levels returned to nonhibernating levels within 2 h, rising from 23.3 ± 1.3 to 410.9 ± 59.2 × 103/μl. However, newly synthesized reticulated platelets were not detected in circulation for 2–3 days (Fig. 3). Consistent with these findings, hibernating ground squirrel bone marrow sections showed a 5.5-fold drop in megakaryocyte density from 75.9 ± 54.3 /mm2 to 13.8 ± 6.1 /mm2 (P < 0.05), indicating a substantial decrease in thrombopoesis during hibernation (Fig. 4). The size of the megakaryocytes remaining in the bone marrow during hibernation was not significantly changed (204.7 ± 72.8 μm2 in nonhibernating vs. 245.5 ± 22.8 μm2 in hibernating) indicating that mature megakaryocytes were still present during hibernation. The bone marrow sections also revealed an increase in adipocytes and a corresponding decrease in cellularity during hibernation.

Fig. 3.

Circulating platelet and reticulated platelet counts in ground squirrels after arousal from hibernation. Platelet counts were measured using a HemaVet on whole blood samples collected in acid-citrate-dextrose. Reticulated platelets were detected by thiazole orange staining and flow cytometry in whole blood samples fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Inset expands the first 48 h postarousal. Means ± SD from 8–14 animals are shown.

Fig. 4.

Bone marrow from nonhibernating and hibernating ground squirrels. Bone marrow sections from femurs were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and imaged with ACT-1 software and a Nikon DXM1200 camera attached to a Nikon 80i microscope using ×20 and ×40 0.75 Plan Apo objectives. During hibernation, the number of megakaryocytes (arrowheads) decreases. In contrast, adipocytes (AD) and reticulocytes or red blood cells (arrows) increase in number during hibernation. Top: bar = 100 μm. Bottom: bar = 25 μm.

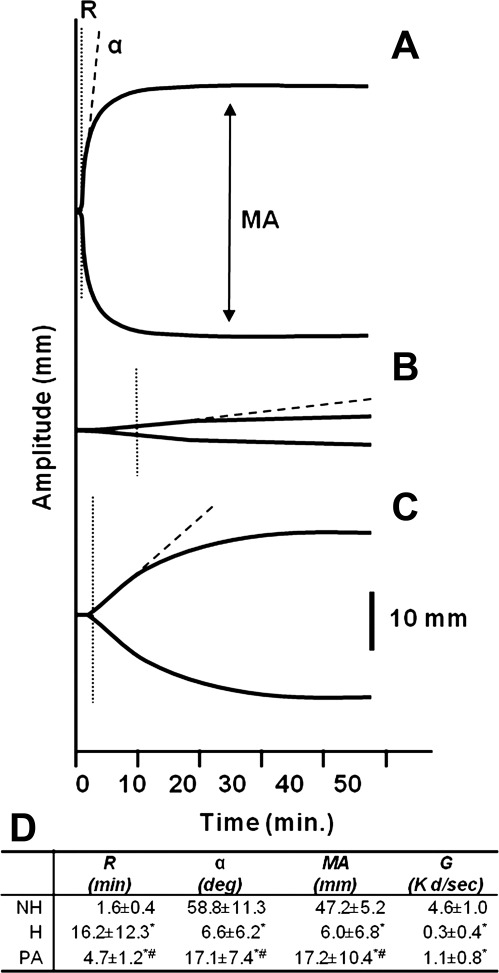

The platelets that were released back into circulation upon arousal were capable of forming a stable clot, as measured by thromboelastography (TEG). Blood from nonhibernators showed both a rapid rate of clot formation, with a short clotting time (R) and steep angle (α), as well a formation of a strong clot, indicated by a large maximum amplitude (MA) (Fig. 5A). As predicted by the suppression of both primary and secondary hemostasis during hibernation, R was 15 min longer, α angle was substantially reduced, and MA decreased eightfold in blood from torpid hibernators (Fig. 5B). Two hours postarousal, body temperatures returned to 37°C, platelet levels returned to nonhibernating levels, and the TEG values fell between those of hibernating and nonhibernating animals (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Thromboelastographs of whole blood from nonhibernating (NH) (A), hibernating (H) (B), and 2 h postarousal (PA) ground squirrels (C). Blood was collected in 0.109 M citrate, 340 μl was recalcified to 20 mM Ca2+, and clotting was initiated with 10 μl of activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) reagent. Platelets were counted on a HemaVet. D: values extrapolated from the curves include time to initiation of clotting (R), rate of clot formation (α), and strength of clot or maximum amplitude (MA), which can be converted into dynes/cm2 (G). Values are means ± SD from 7 to 8 animals in each group. Superscripts indicate values that were significantly different from NH (*) or H (#) (t-test; P < 0.05).

Temperature sensitivity of platelet clearance in rats and ground squirrels.

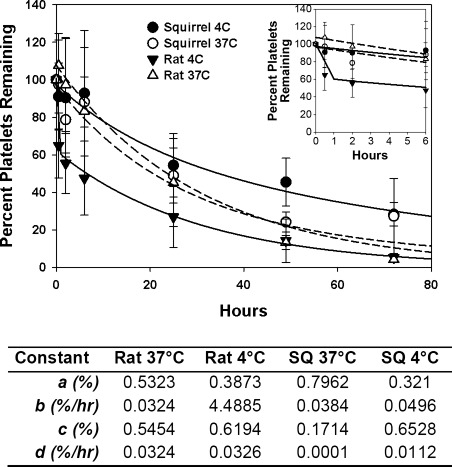

Human, baboon, and mouse platelets that are cooled for 2 h at 4°C, labeled, and injected back into circulation are rapidly cleared (2, 4, 10, 21). We replicated these experiments in rats and ground squirrels, using two different fluorescent labels for cold and warm platelets, which allowed simultaneous comparisons to be made in the same animal. Platelets obtained from normothermic nonhibernating ground squirrels, stored for 2 h at 4°C and 37°C, labeled with two different fluorophores, and then simultaneously transfused were cleared at the same rates (Fig. 6). The data were fit to a biexponential curve (y = ae−bx + ce−dx), and the rates of clearance (b and d) of subpopulations of platelets (a and c) were calculated. After storage at either temperature, the ground squirrel platelets were cleared at approximately the same rate (0.064–0.083 %/min) as rat platelets stored at 37°C (0.054 %/min). In contrast, 39% of rat platelets stored at 4°C were cleared very rapidly (7.48 %/min), a 140-fold increase in clearance rate compared with storage at 37°C. The remaining 60% of chilled rat platelets were cleared at the same rate as rat platelets stored at 37°C.

Fig. 6.

Clearance of autologous rat and ground squirrel platelets stored for 2 h at 4°C and 37°C. Top: separate aliquots of stored platelets were labeled with CM-green or Bodipy 630/650 and transfused back into the same animal. Samples were taken at different time points, and the fraction of labeled platelets was determined by flow cytometry and normalized to the zero time point measured 10 min posttransfusion. Inset expands the first 6 h posttransfusion. Bottom: values from fitting data to a bioexponential curve a and c are the fraction of the labeled platelets removed at the rates b and d, respectively. Values are means ± SD from 5 to 6 animals, rate b was significantly different for rats at 4°C (t-test P < 0.05).

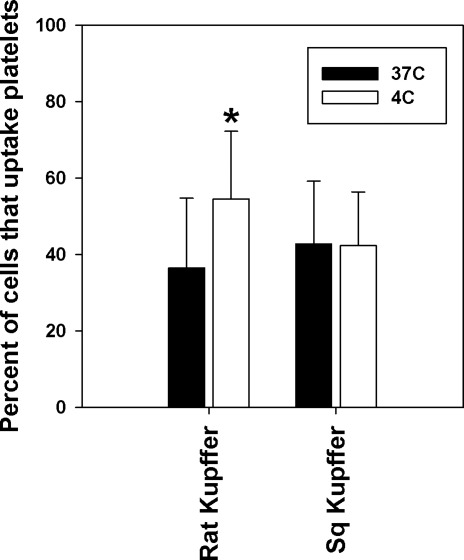

To evaluate the in vitro clearance of chilled ground squirrel versus rat platelets, we purified primary cultures of rat and ground squirrel Kupffer cells from collagenase-perfused livers and incubated them with fluorescently labeled platelets stored at 4°C or 37°C for 2 h. By flow cytometry, 50% more rat Kupffer cells took up platelets stored at 4°C than platelets stored at 37°C. In contrast, ground squirrel platelet uptake by Kupffer cells was not influenced by the storage temperature of the platelets (Fig. 7), consistent with our in vivo findings.

Fig. 7.

Binding and uptake of labeled platelets by Kupffer cells. Kupffer cells were isolated from the livers of rats or ground squirrels (Sq) and allowed to attach in 12-well plates, n = 3 of each species. Platelets were isolated and incubated for 2 h at 4°C or 37°C, labeled with CM-Orange, and incubated with the Kupffer cells for 30 min. The Kupffer cells were washed, and the percentage of the cells that contained orange fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. Each preparation of Kupffer cells was assayed with platelets isolated from three animals of the same species. Values reflect means ± SD of nine assays. *Significant difference (t-test; P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Ground squirrel platelet MTs are cold tolerant.

The MT reorganization observed in ground squirrel platelets upon storage in the cold was atypical compared with platelet MTs from mammals that cannot hibernate, which irreversibly depolymerize in the cold (19, 24). The MT rod formation may play a role in trapping platelets in the spleen as body temperature drops, and their return to the circumferential ring at normothermic temperatures likely allows for platelet release upon arousal. In addition, the MT reorganization may also play a role in preventing platelet clearance upon rewarming. When mouse platelets are chilled, their surface vWF receptors (GPIbα-V-IX complex) move from a linear arrangement to form clusters. This clustering correlates with clearance through binding of platelet vWF receptors to CR3 receptors on the Kupffer cells (8). One possible explanation for this behavior could be that the cytoplasmic tails of the vWF receptors are anchored to the cytoskeleton, and when MTs depolymerize in the cold this scaffolding breaks apart allowing the vWF receptorsto cluster. By maintaining a linear MT structure during hibernation, the ground squirrel vWF receptors may not cluster, preventing clearance through the CR3 receptor.

Ground squirrel platelets are stored at cold temperatures and released back into circulation upon warming.

The observation that the rapid increase in platelets after spring arousal was due to release of stored platelets and not new platelet synthesis is supported by the platelet life spans in mice and humans of approximately 4 and 7 days (1, 4). Based on these steady-state replacement rates and our observations of low numbers of bone marrow megakaryocytes and reticulated platelets, it is unlikely that the observed rapid increase in platelet levels within 2 h of arousal could reflect new platelet synthesis. Furthermore, platelet levels remained constant after 2–6 h postarousal, indicating that the released platelets were not rapidly cleared from circulation. Taken together, the temperature-dependent sequestration and release of platelets, coupled with the delay in new platelet synthesis strongly, suggest that ground squirrel platelets were stored during hibernation at a body temperature of 4–8°C and were released into circulation upon warming without being rapidly cleared.

Functional primary hemostasis was restored within hours of arousal from hibernation.

In a thromboelastograph, the MA measures clot strength and correlates with platelet activity (3, 5, 17). The threefold increase in MA observed 2 h after the animals were aroused indicated that the platelets released back into the blood postarousal were still functional. The strength of the clot [in dyn/cm2 (G)] can be calculated from the MA (11). When compared with nonhibernating animals (4.6 dyn/cm2), clot strength was found to be reduced 15-fold during hibernation (0.3 dyn/cm2) and 4-fold in samples taken from animals 2 h postaroual (1.1 dyn/cm2). Secondary hemostasis also recovered partially within 2 h postarousal, as evidenced by the decrease in R and increase in α. However, the time to form a stable clot (K) was prolonged fivefold in postarousal animals (15.0 min) when compared with nonhibernating controls (2.9 min). Thus, while ground squirrel hemostasis is quite resilient to the effects of prolonged hibernation, both the kinetics of clot formation and clot strength do not immediately return to nonhibernating normothermic levels upon arousal in the spring. This is not unexpected when viewed from adaptation and natural selection, in that an animal may not need to completely restore full hemostasis activity upon arousal, just enough activity to prevent bleeding. Over time, as new platelets and clotting factors are produced, the ground squirrels will regain the hemostasis profile of a normothermic rodent.

Ground squirrel platelets are not cleared rapidly after cold storage.

The clearance rates of ground squirrel platelets were not altered significantly by storage for 2 h at 4°C and were approximately the same as that observed in the rat, a similar sized rodent. By fitting the data to a biexponential curve it was apparent that there were two pools of platelets in the chilled rat samples, one that was cleared very rapidly as expected, but a second pool that was cleared from circulation at the normal rate. This was intriguing, as it suggested an all-or-nothing response in short-term cold storage effects on platelets. After 2 h of storage in the cold, a rat platelet was either altered in a way that caused it to be cleared rapidly, or it was not affected and was cleared at a normal rate.

Perspectives and Significance

Many cold-induced structural and functional changes occur in human platelets, leading to increased aggregation and degranulation upon warming (22). Because of the negative effects of cold storage, human platelets are currently stored at room temperature, increasing the risk of bacterial contamination and loss of function (18, 20). As a result, platelets are limited to a 5-day shelf life (7), with 15% of the platelet supply expiring before they can be used (23). In this study we showed that ground squirrel platelets appear to be resistant to cold-induced clearance in vivo and in vitro and were still functional after prolonged storage in the cold. This allows the ground squirrels to reduce platelet counts and the associated risk of clotting during torpor, and yet restore a functional hemostasis pathway when they warm up. Determining the mechanisms underlying this resistance to cold could have direct clinical applications in the storage of human platelets at 4°C. Future experiments will need to determine the impact of longer term storage of ground squirrel platelets at 4°C, as well as hibernation-induced changes to the platelets and cells responsible for removing chilled platelets from circulation. While the potential medical applications are intriguing, the natural adaptations that allow hibernating mammals to shift rapidly from an anticoagulant hypothermic state to one of functional hemostasis at a normal body temperature are equally remarkable. It remains to be seen if similar mechanisms have evolved in other vertebrates that hibernate or enter torpor to avoid stasis-induced blood clots.

GRANTS

The project described was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R15 HL-093680 (to S. Cooper). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. This work was also funded by an Applied Research Grant (ARG) and Combined Applied Research Grant-WiSys Technology Advancement Grant (ARG-WiTAG) (to support P. Hordyk) and UWL Dean's Summer Fellowships (to R. Benrud and L. Geiser).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.T.C., P.J.H., R.R.B., M.H.E., and M.C.S.-V. conception and design of research; S.T.C., K.E.R., T.E.M., Z.-j.L., P.J.H., R.R.B., L.R.G., S.E.C., D.R.H., M.H.E., and M.C.S.-V. performed experiments; S.T.C., K.E.R., T.E.M., Z.-j.L., P.J.H., R.R.B., L.R.G., C.S.S., D.R.H., M.H.E., and M.C.S.-V. analyzed data; S.T.C., K.E.R., T.E.M., Z.-j.L., P.J.H., R.R.B., L.R.G., M.H.E., and M.C.S.-V. interpreted results of experiments; S.T.C., L.R.G., D.R.H., M.H.E., and M.C.S.-V. prepared figures; S.T.C. drafted manuscript; S.T.C., K.E.R., T.E.M., C.S.S., D.R.H., M.H.E., and M.C.S.-V. edited and revised manuscript; S.T.C., K.E.R., T.E.M., Z.-j.L., P.J.H., R.R.B., L.R.G., S.E.C., C.S.S., D.R.H., M.H.E., and M.C.S.-V. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Amy Cooper, UW-La Crosse, for her care of the ground squirrels and surgical expertise. Lisa Frisch, Telina Awowale, and Theresa Gonzales, UW-LaCrosse assisted with the bone marrow histology. Tom Volk, UW-La Crosse is thanked for his critical review of the manuscript. Dana Vaughan, UW-Oshkosh, helped establish the breeding colony of ground squirrels at UW-La Crosse. De Anna Haugen, Laurnice Olsen, and Whyte Owen, Mayo Clinic, assisted with the TEG assays.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aas KA, Gardner FH. Survival of blood platelets labeled with chromium. J Clin Invest 37: 1257– 1268, 1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Becker GA, Tuccelli M, Kunicki T, Chalos MK, Aster RH. Studies of platelet concentrates stored at 22°C and 4°C. Transfusion 13: 61– 68, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beilin Y, Arnold I, Hossain S. Evaluation of the platelet function analyzer (PFA-100) vs. the thromboelastogram (TEG) in the parturient. Int J Obstet Anesth 15: 7– 12, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berger G, Hartwell DW, Wagner DD. P-Selectin and platelet clearance. Blood 92: 4446– 4452, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowbrick VA, Mikhailidis DP, Stansby G. Influence of platelet count and activity on thromboelastography parameters. Platelets 14: 219– 224, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crowe JH, Crowe LM, Wolkers WF, Oliver AE, Ma X, Auh JH, Tang M, Zhu S, Norris J, Tablin F. Stabilization of dry Mammalian cells: lessons from nature. Integr Comp Biol 45: 810– 820, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engelfriet CP, Reesink HW, Blajchman MA, Muylle L, Kjeldsen-Kragh J, Kekomaki R, Yomtovian R, Hocker P, Stiegler G, Klein HG, Soldan K, Barbara J, Slopecki A, Robinson A, Seyfried H. Bacterial contamination of blood components. Vox Sang 78: 59– 67, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoffmeister KM, Felbinger TW, Falet H, Denis CV, Bergmeier W, Mayadas TN, von Andrian UH, Wagner DD, Stossel TP, Hartwig JH. The clearance mechanism of chilled blood platelets. Cell 112: 87– 97, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lechler E, Penick GD. Blood clotting defect in hibernating ground squirrels (Citellus tridecemlineatus). Am J Physiol 205: 985– 988, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Melaragno AJ, Abdu W, Katchis R, Doty A, Valeri CR. Liquid and freeze preservation of baboon platelets. Cryobiology 18: 445– 452, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nielsen VG, Geary BT, Baird MS. Evaluation of the contribution of platelets to clot strength by thromboelastography in rabbits: the role of tissue factor and cytochalasin D. Anesth Analg 91: 35– 39, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pivorun EB, Sinnamon WB. Blood coagulation studies in normothermic, hibernating, and aroused Spermophilus franklini. Cryobiology 18: 515– 520, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reddick RL, Poole BL, Penick GD. Thrombocytopenia of hibernation. Mechanism of induction and recovery. Lab Invest 28: 270– 278, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rumjantseva V, Grewal PK, Wandall HH, Josefsson EC, Sorensen AL, Larson G, Marth JD, Hartwig JH, Hoffmeister KM. Dual roles for hepatic lectin receptors in the clearance of chilled platelets. Nature Med 15: 1273– 1280, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rumjantseva V, Hoffmeister KM. Novel and unexpected clearance mechanisms for cold platelets. Transfus Apher Sci 42: 63– 70, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saxonhouse MA, Sola MC, Pastos KM, Ignatz ME, Hutson AD, Christensen RD, Rimsza LM. Reticulated platelet percentages in term and preterm neonates. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 26: 797– 802, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharma SK, Philip J, Whitten CW, Padakandla UB, Landers DF. Assessment of changes in coagulation in parturients with preeclampsia using thromboelastography. Anesthesiology 90: 385– 390, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Springer DL, Miller JH, Spinelli SL, Pasa-Tolic L, Purvine SO, Daly DS, Zangar RC, Jin S, Blumberg N, Francis CW, Taubman MB, Casey AE, Wittlin SD, Phipps RP. Platelet proteome changes associated with diabetes and during platelet storage for transfusion. J Proteome Res 8: 2261– 2272, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thon JN, Montalvo A, Patel-Hett S, Devine MT, Richardson JL, Ehrlicher A, Larson MK, Hoffmeister K, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE., Jr Cytoskeletal mechanics of proplatelet maturation and platelet release. J Cell Biol 191: 861– 874, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thon JN, Schubert P, Devine DV. Platelet storage lesion: a new understanding from a proteomic perspective. Transfus Med Rev 22: 268– 279, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Valeri CR, Ragno G, Marks PW, Kuter DJ, Rosenberg RD, Stossel TP. Effect of thrombopoietin alone and a combination of cytochalasin B and ethylene glycol bis(beta-aminoethyl ether) N,N′-tetraacetic acid-AM on the survival and function of autologous baboon platelets stored at 4 degrees C for as long as 5 days. Transfusion 44: 865– 870, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vostal JG, Mondoro TH. Liquid cold storage of platelets: a revitalized possible alternative for limiting bacterial contamination of platelet products. Transfus Med Rev 11: 286– 295, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whitaker BI, Green J, King MR, Leibeg LL, Mathew SM, Schlumpf KS, Schreiber GB. The 2007 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey Report. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 24. White JG, Rao GH. Microtubule coils versus the surface membrane cytoskeleton in maintenance and restoration of platelet discoid shape. Am J Pathol 152: 597– 609, 1998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wolkers WF, Walker NJ, Tablin F, Crowe JH. Human platelets loaded with trehalose survive freeze-drying. Cryobiology 42: 79– 87, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zatzman ML. Renal and cardiovascular effects of hibernation and hypothermia. Cryobiology 21: 593– 614, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]