Abstract

Objectives. We explored the relationship between tobacco companies and the Black press, which plays an important role in conveying information and opinions to Black communities.

Methods. In this archival case study, we analyzed data from internal tobacco industry documents and archives of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), the trade association of the Black press.

Results. In exchange for advertising dollars and other support, the tobacco industry expected and received support from Black newspapers for tobacco industry policy positions. Beginning in the 1990s, resistance from within the Black community and reduced advertising budgets created counterpressures. The tobacco industry, however, continued to sustain NNPA support.

Conclusions. The quid pro quo between tobacco companies and the Black press violated journalistic standards and represented an unequal trade. Although numerous factors explain today's tobacco-related health disparities, the Black press's service to tobacco companies is problematic because of the trust that the community placed in such media. Understanding the relationship between the tobacco industry and the NNPA provides insight into strategies that the tobacco industry may use in other communities and countries.

Tobacco use is a leading cause of health disparities affecting African Americans.1–4 Older African Americans (≥ 44 years) have the highest smoking rates of any group (about 30%).5 Among lower-income African Americans, smoking rates are as high as 59%.6,7 Over 45 000 African Americans die from tobacco-related diseases each year,3,8,9 which constitutes the highest smoking-related disease burden of any US group.7,10–12 African American communities also disproportionately bear lost productivity from tobacco-caused diseases. Although constituting only 6% of California's population, African Americans account for 8% of smoking-attributable expenditures and 13% of smoking-attributable mortality costs.13

Although smoking prevalence results from complex interactions of multiple factors, including socioeconomic status, cultural characteristics, acculturation, stress, advertising, cigarette prices, parental and community disapproval, and abilities of local communities to mount effective tobacco-control initiatives,14 the disproportionate tobacco-related disease burden among African Americans suggests the need for closer examination of the factors related to smoking prevalence that may be unique to the community. One factor in creating a climate in which smoking seems acceptable is the influence of the tobacco industry on cultural and social institutions,15 including the media.

African American communities have long been targeted with tobacco advertisements, products, and philanthropy.7,16–18 Tobacco companies have also sought to influence journalism19 and sustain extensive ties with African American leadership groups15 to undermine tobacco control. Although some research has previously recognized tobacco company support of minority-targeted media,20,21 no previous studies have examined the longstanding relationship between tobacco companies and the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), the most important Black media organization. We explored the role of tobacco industry patronage of African American newspaper publishers and the expectations that such patronage involved. (Note that we use the terms Black and African American here interchangeably, as is common in US minority health research.22 Additional terms may be used, depending on the context and historical period; for instance, Negro was a common term used to refer to people of African descent through the 1970s.)

BACKGROUND

The African American experience was irrevocably shaped by the legacy of slavery, which itself was perpetuated by labor demands from tobacco plantations.8,23 From the founding of the United States, African Americans’ fortunes have been linked with tobacco. The fortunes of African American media have likewise been intertwined with tobacco-company interests, long after slavery's abolishment.8,23

The Black press was established in New York City in 1827, at a time when public media were unavailable to Blacks.24–26 The first African American newspaper, Freedom's Journal, proclaimed, “Too long have others spoken for us.”24–26 The Black press gave voice to a marginalized community, “molding self-esteem and public opinion… setting the public agenda”27(p203) and advocating for rights rarely addressed in White mainstream media.24 By 1910, more than 275 Black newspapers reached over 500 000 people25 and became trusted sources of information for the community.26,28,29

For decades, however, many Black newspapers struggled because few White-owned businesses advertised in African American media. The tobacco industry was one early exception.3,30–32 Tobacco companies were early supporters of civil rights for Blacks and were among the first companies to desegregate facilities.8,33 This early support was undoubtedly critical to sustaining civil rights discourse in Black media and could thus be interpreted as representing a laudable commitment by tobacco companies, as the tobacco industry later frequently claimed. However, as documented in other work,15,34 an alternative or coexisting interpretation is that cultivating these media relationships was primarily a matter of accessing a “new” market for tobacco and later of controlling potential community opposition.

In 1941, the National Negro Publishers Association was established, later becoming the NNPA.26 The NNPA currently represents more than 200 African American newspapers, with a US circulation totaling 15 million.26,35 Circulation figures likely understate its reach, however, because NNPA papers are often free and passed around the community.36 The NNPA has moved into electronic media with BlackPressUSA.com.26 African American newspapers reach an estimated 25% to 28% of all African Americans.37,38

METHODS

Between July 2009 and June 2010, we searched previously confidential tobacco company documents archived in the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (LTDL; http://www.legacy.library.ucsf.edu). Released following the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, these documents constitute more than 60 million pages, and more are still being added.39–41 Using snowball sampling,40 beginning with the search terms “Black press” and “Negro press,” we retrieved documents and identified additional search terms, including “NNPA” and the names of individuals. After screening for relevance and duplication, we reviewed more than 250 documents dated from 1968 to 2004 that referenced NNPA. We also searched Web sites related to the Black press and the NNPA.

In addition, during April 2010 the first author visited Howard University's Black Press Archives in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division and searched 35 NNPA-related boxes for tobacco company names and relevant correspondence with individuals identified through the LTDL. We reviewed over 500 pages from these archives. Materials were analyzed thematically to prepare this descriptive case study.

RESULTS

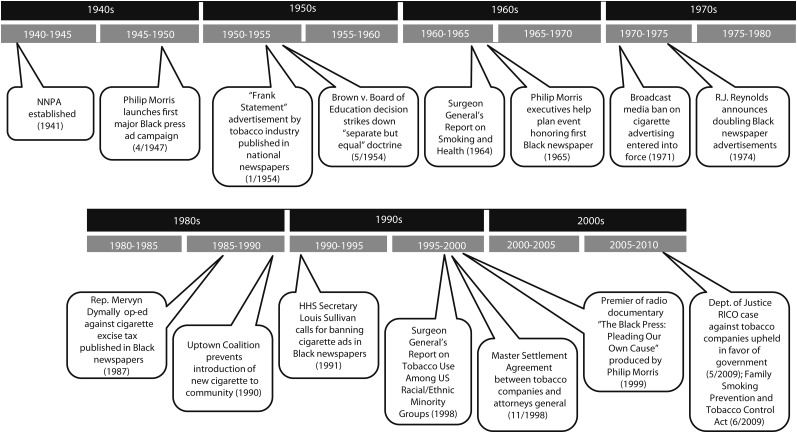

Almost from its inception, the NNPA and its newspapers had relationships with tobacco companies (Figure 1).3,18,26,32,39–69 Tobacco companies began advertising in African American media in the 1940s, recognizing a burgeoning market.3,8,15,31,32,70,71(p337) Philip Morris announced a major Black press campaign in 1947, including the NNPA paper Chicago Defender.32 Few companies then advertised in Black newspapers25,30,31; tobacco companies later frequently reminded publishers of this early support.72–75

FIGURE 1.

Key dates in Black press and tobacco control history.

Source. See References list for sources.3,18,26,32,39–69,189

The patronage tobacco companies provided came with expectations of support for industry positions. Black papers, in turn, developed reciprocal expectations of the industry. The now-infamous “Frank Statement” ad of 1954 (a public relations effort by major tobacco companies aimed at dispelling worries about links between smoking and lung cancer) was published in more than 400 newspapers in 258 cities, but not in the Black press.42,76–78 The ad announced the establishment of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee, now known to be part of an industry conspiracy to deceive the public about the risks of smoking.42,79 Black newspapers were apparently excluded from this ad buy because the industry assumed major newspapers reached Blacks.80 However, excluding Black papers caused problems, as Philip Morris executives observed:

[A]ll Negro newspaper people are greatly peeved because the Tobacco Association announcement ad wasn't run in the Negro press… . Hill and Knowlton [the tobacco industry's public relations firm] is going to have a very tough time getting any editorial support from the Negro press.81

There was apparently discussion later of adding publications to the circulation of the “Frank Statement,”80 but we found no evidence that it appeared in the Black press. Thus began a pattern of treating the Black press differently while expecting its ongoing support.

Solidifying Relationships

During the civil rights era of the 1960s, the tobacco industry initiated a number of NNPA-related sponsorships. For example, Philip Morris executives helped plan a 1965 event honoring the founders of the first Black newspaper; free cigarettes were distributed at the event.43 Later in the 1960s, when a public relations firm recommended that R. J. Reynolds become involved with “Negro assemblies” to benefit the company, the NNPA was the first organization listed.82

After the broadcast cigarette advertising ban in 1971,44 print media became even more important to tobacco companies, and the companies cultivated NNPA relationships through more forms of support.20 For example, R. J. Reynolds partnered with the NNPA in 1972 to establish an undergraduate journalism scholarship.83,84 R. J. Reynolds executives attended NNPA conventions to present scholarship checks.85–95 During this time, R. J. Reynolds executives announced a doubling of advertisements in NNPA papers.45–54 Correspondence with the NNPA president in 1974 showed that R. J. Reynolds executives anticipated ongoing benefits:

The black press has been one of the best and fastest methods by which to communicate to the black consumers… the R. J. Reynolds Scholarship Program in Journalism… is a most worthwhile investment for us in that it will produce the quality journalists needed by you to help us continue to sell our products by advertisements and other articles in the black press.89

Tobacco companies also sponsored NNPA awards,96 including Brown & Williamson sponsoring the annual Best Feature Story,83,97–104 American Tobacco sponsoring Best Sports Page,97–99,101,103,104 and Philip Morris sponsoring Best Editorial83,97–99,101,103–105 and Best News Story.100 Tobacco executives often spoke at events celebrating individual journalists and the Black press.86,106–108

At least into the late 1990s, tobacco executives used speeches at NNPA events to argue that tobacco advertising restrictions would harm the Black press and that excise taxes were regressive because they would have disproportionate effects on poor African Americans.108–115 Common themes included smoking as a “right” and the industry's right to advertise,116–118 tobacco company philanthropy,117 free speech and resisting “unreasonable” policies such as advertising restrictions117,119–121 and tobacco taxes.122–127 The R. J. Reynolds CEO's 1998 remarks to the NNPA opposing increased tobacco taxes,122–124 for example, explicitly reminded the group of the tobacco industry's longstanding relationship with the Black press.122(p1) The vice president of external affairs for Philip Morris Management Corporation, Tina Walls, also spoke at 2 NNPA conferences in 1999,128,129 referencing the “trust, shared values, and common goals”128 between Philip Morris and the NNPA, while asking the NNPA to communicate Philip Morris's “social responsibility” message and “other issues relating to [their] various products.”129

Tobacco companies also sponsored meals and provided conference gifts, and industry executives—usually African American—and consultants organized meetings between NNPA leaders and tobacco executives. For example, Stan Scott, an African American with a journalism and Black press background who worked for Philip Morris, established personal relationships with NNPA leaders90,95,130–133 and sent materials “regarding the ‘Great Tobacco Debate,’”100 presumably encouraging support for the industry's position that scientific understanding about disease risks from smoking was still “controversial.” The NNPA welcomed them.100

NNPA support for tobacco industry positions, advertising, and philanthropy were linked. In 1979, J. Paul Sticht, chairman/CEO of R. J. Reynolds Industries, planned to meet with 4 leading NNPA publishers.134 Sticht told a colleague that the publishers wanted to discuss (1) “How the Black Press can support the Tobacco Industry in the smoking-health controversy,” (2) “General advertising,” and (3) the “R. J. Reynolds Industries–NNPA Scholarship Program in Journalism.”134

Quid Pro Quo: Tobacco Industry Expectations

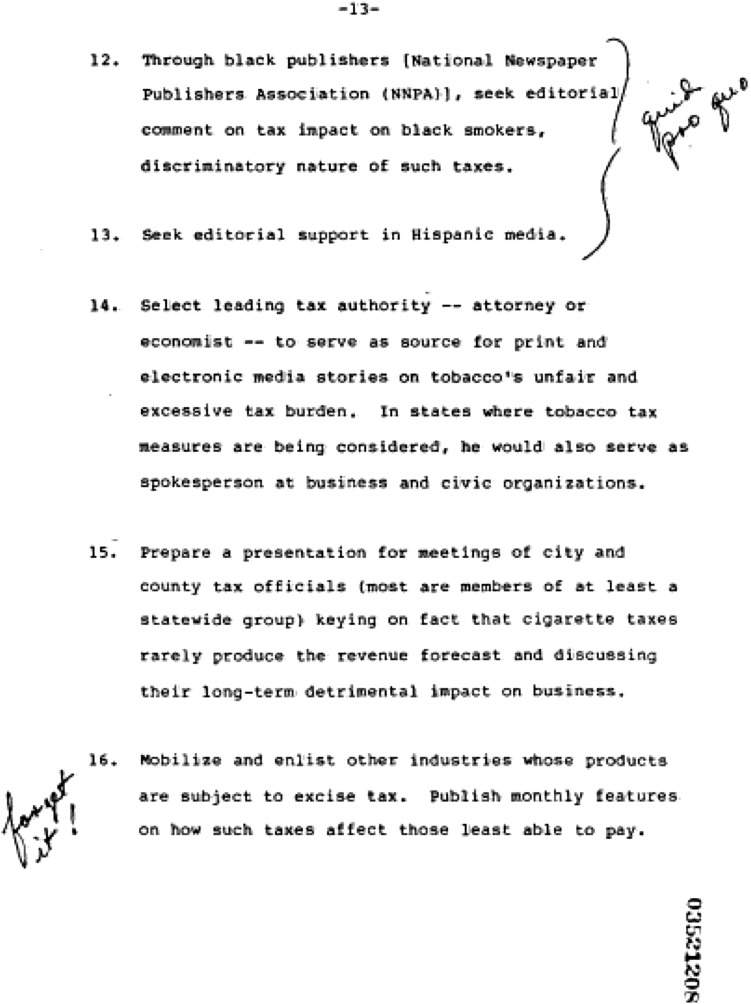

The Tobacco Institute (TI), the industry's multicompany-supported lobbying group, in 1983 suggested that tobacco companies could indeed expect editorial support from the Black press. The TI Communications Plan for High Priority Issues, under a section entitled “Tactics,” recommended

Through black publishers (National Newspaper Publishers Association [NNPA]), seek editorial comment on tax impact on black smokers, discriminatory nature of such taxes.135(p13)

A handwritten margin note said, “quid pro quo” (Figure 2).135(p13) (Quid pro quo means “something for something of more or less equal value.”136(p1282))

FIGURE 2.

Excerpt from the Tobacco Institute's 1983 communications plan for high-priority issues, including a note about “quid pro quo,” suggesting that the NNPA would print editorials supporting the tobacco industry.

Note. NNPA = National Newspaper Publishers Association.Source. The Communications Committee of the Tobacco Institute for the Tobacco Institute Public Relations Division. A Tobacco Institute Interim Communications Plan Addressing Four High Priority Issues. November 15, 1983. Lorillard. Bates no. 03521195/1214. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ydc81e00. Accessed October 7, 2009.135

The TI planned to

place a minimum of two stories annually pointing out [the] heavy burden placed on middle and lower income smokers by cigarette taxes with print and electronic media nationally, with concentration on minority media [italics added].135(p12)

It is unclear whether “stories” indicated articles or the “editorial comment” the TI later planned to seek from the NNPA,135 but the plan appeared intended to influence content.137(p7) “Leaders of Black publications,” according to the TI, were “very influential individuals… sensitive to the political impact of the contents of their papers.”138 In fact, “influence is more important than numbers as far as newspaper ads are concerned,” so the TI intended to “use these publications for issues, editorials, ads…, and, of course, providing information or comment on proposed legislation.”138

The TI proceeded,139 providing information on proposed legislation and seeking NNPA assistance in opposing it (e.g., a 1986 NNPA resolution opposing an advertising ban140,141) and encouraging NNPA papers to run industry-favorable editorials. In 1985, for example, a St. Louis Sentinel editorial asserted that the Black press would continue to advertise cigarettes to avert greater harm:

the merchants of anti-smoking should do their total homework, and realize the irreparable harm that can occur to the Black Press if they have their way.142

The TI worked to maintain the NNPA relationship because it paid off for tobacco companies:

The [NNPA] as a whole, and various individuals, have already shown an understanding of our issues, and a willingness to help… . NNPA support on the advertising, public smoking, and tax issues could only be a plus… . The NNPA, several members of the [NNPA] board, and individual publishers have actively opposed advertising restrictions of tobacco products, workplace smoking restrictions that disproportionately affect minorities, and public smoking restrictions that mandate personal behavior.143

In a memo, TI Public Affairs Senior Vice President Susan Stuntz supported purchasing a table at a Black press event to show appreciation: “Our participation… at the request of the NNPA's president, would be a small gesture of our thanks.”144 “Appreciation” was due from tobacco companies not because the NNPA papers printed paid advertisements, but because they supported the industry.142,145,146

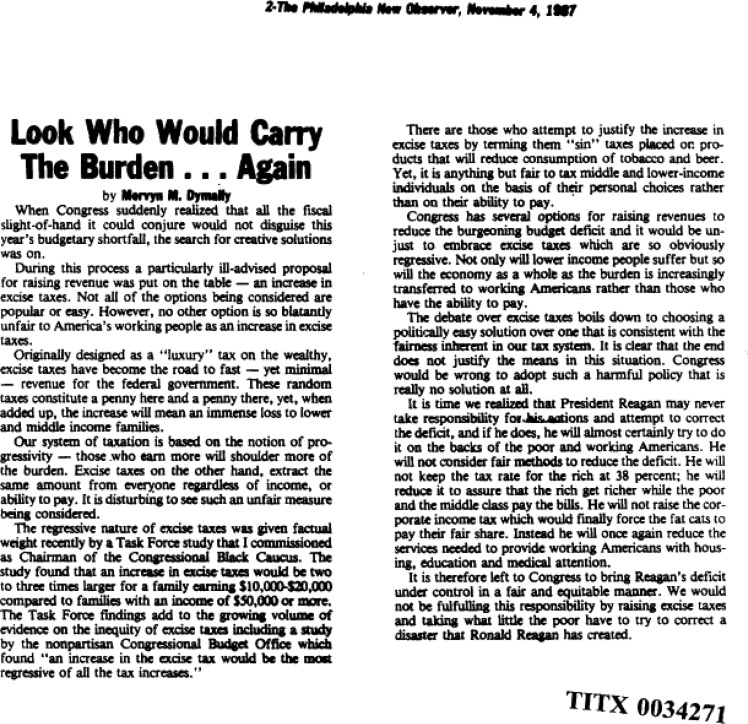

Given tobacco patronage and the TI's solicitation of particular positions in editorial comment, it would likely have been problematic for NNPA papers not to write supportive editorials. There is suggestive evidence that op-eds supporting the tobacco companies were ghostwritten—unsigned—by the tobacco industry or its consultants, and then bylined by influential black leaders.147a For example, the TI's public affairs firm, Ogilvy & Mather, was involved with coordinating an op-ed signed by Congressman Mervyn M. Dymally15,147b arguing against a federal tobacco excise tax, which was published in 20 Black publications.55,147c Identical in all newspapers, it featured Dymally's byline, with no reference to Ogilvy & Mather or its client. Titled “Look Who Would Carry The Burden… Again,” the op-ed described excise taxes as regressive, only briefly mentioning tobacco (Figure 3).55–61 Although some papers might not have known that the piece was ghostwritten by an industry public relations firm, some NNPA publishers actually requested op-eds from the TI.148,149

FIGURE 3.

1987 op-ed published in Black newspapers and signed by Congressman Mervyn M. Dymally, which involved the Tobacco Institute's public relations firm.

Source. Dymally MM. Philadelphia New Observer. Look Who Would Carry the Burden…Again. November 4, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034271. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qxw32f00. Accessed March 8, 2010.60

A 1995 Philip Morris e-mail planned “message points and canned opinion pieces” that West Coast Black Publishers (an NNPA subgroup) members could sign. Referring to the NNPA and the national Hispanic publishers’ group, the e-mail said

With all the advertising we offer them, they will run any editorial we like. They all need to be different however because they run as editorials rather than guest opinion pieces.150

Op-eds suggested by R. J. Reynolds for NNPA publication included “Federal Government Has No Basis for Tobacco Industry Lawsuit” (opposing federal litigation against tobacco companies)151,152 and an op-ed against tobacco class action litigation.153

Developing Tensions

While the NNPA appeared supportive of the industry into the 1980s, it expected sustained or increased support. Carlton B. Goodlett, a physician and NNPA leader,154,155 corresponded frequently with tobacco companies about equal opportunities for Blacks and Black publications. Typically, companies took his complaints seriously.156–164 Philip Morris, for example, was concerned that Goodlett would cause a commotion about the withdrawal of some advertising from Black papers at a shareholders’ meeting.159,160 A 1987 Philip Morris document indicated that additional NNPA papers should receive advertising because

[t]hey've run editorials and/or Op Ed pieces on proposed ad bans and the dangers of censorship; spoken out vehemently against smoking restrictions on airlines and in restaurants; written and called state legislative leaders concerning these issues; religiously run press releases, news releases and given coverage to events sponsored by our company; and attended various company sponsored events to show their support.165

In the mid- to late 1980s, counterpressure from within African American communities emerged, straining the NNPA–tobacco industry relationship.18,166 African American public health leaders began challenging tobacco company target marketing. The numbers of NNPA-related LTDL documents from the 1980s and 1990s suggest the organization's continued importance to the tobacco industry (Table 1). TI memos about the 1988 NNPA convention reported that health advocates had accused the Black press of “selling out” the community by accepting tobacco advertisements.148,149 When Secretary of Health and Human Services Louis Sullivan (an African American) called for banning cigarette advertising in Black newspapers162 and for the recognition of Black-targeted tobacco marketing,18,63–65 the industry recognized that “ugl[iness]”66 and threats167 to its legitimacy were growing.168

TABLE 1.

Unique Documents With NNPA in the Text Found in Legacy Tobacco Documents Library by Year: 2010.

| Years | Documents, No. |

| 1951–1955 | 2 |

| 1956–1960 | 9 |

| 1961–1965 | 17 |

| 1966–1970 | 17 |

| 1971–1975 | 44 |

| 1976–1980 | 81 |

| 1981–1985 | 163 |

| 1986–1990 | 334 |

| 1991–1995 | 394 |

| 1996–2000 | 456 |

| 2001–2005 | 33 |

Note. NNPA = National Newspaper Publishers Association.

NNPA publishers expected tobacco companies’ support as they endured such criticism, as a conflict over ad budgets revealed. Philip Morris's advertising in Black newspapers rose from 1988 to 1991169,170 but dropped by about $1 million in 1992.167,171,172 This decrease did not satisfy the NNPA, as a 1992 memo between Philip Morris corporate affairs vice presidents Ellen Merlo and Craig Fuller noted.167 Merlo explained that after the cut,

[t]he publishers were pretty threatening… indicating that they have been out front supporting us on tobacco and corporate issues, and they will not accept a budget cut.167(p1)

The publishers also discussed requesting meetings with Philip Morris's affiliated companies.167 Merlo suggested “pool[ing] resources… that would placate” Black publishers.167(p2) Eventually, Merlo reported to NNPA president Robert Bogle an approximately $500 000 increase in Black newspaper advertising for 1992 to 1993.173

Sustaining Connections

Well into the 1990s, scholarships, advertising, sponsorships, and speaking engagements continued to be used to sustain NNPA–tobacco company connections.174–183 R. J. Reynolds, perhaps responding to its 1989 to 1990 “Uptown” fiasco (a new brand targeting African Americans, aborted following African American community activism),18,63–65 planned a major media campaign in 1990 to inform the “Black community of [R. J. Reynolds]’s heritage of social responsibility and commitment.”184 The program apparently resulted in “extensive favorable publicity.”184 R. J. Reynolds's Journalism Scholarship Program was mentioned in industry documents through at least 1994, establishing a corps of journalists supported by tobacco funding.176–181 Among numerous other contributions, an article from Philip Morris's files noted that R. J. Reynolds sponsored a luncheon at NNPA's 1995 Mid-Winter Workshop, “culminat[ing] with Brown & Williamson host[ing] a fabulous evening cruise around Tampa Harbor.”185

R. J. Reynolds included NNPA leaders, such as former NNPA presidents Bogle and Dorothy Leavell, in discussions about combating the rising community opposition to tobacco. Bogle was quoted as saying, “Tobacco companies were our friends before anybody else was.”186 Leavell was quoted as admitting that “Tobacco ads influence us,”186 but she argued in a New York Times article that the impact of a tobacco advertising ban “would be devastating.”187,188(p12) Philip Morris created an award-winning radio documentary series featuring African Americans, including a program on the Black press, which premiered in 1999.189

Despite growing concerns from the community190 and fluctuating advertising budgets, the ties between the NNPA and the tobacco industry were sustained. Tobacco companies supported key NNPA events almost every year from 1996 to 2000.183,191–197

DISCUSSION

We have documented a longstanding, complicated relationship between the tobacco industry and the Black press, and have revealed the nature of the quid pro quo involved.135 The industry regarded its patronage as ensuring that the Black press remained a reliable ally. Although such editorial support was forthcoming, our study did not permit us to assess the extent of this support.

It would be unfair to assume that Black newspapers were alone in facing pressure from advertisers; these tensions always exist between media and their advertising patrons.20,34,198,199 However, earlier research on Ebony and Life magazines demonstrated the trajectory of cigarette advertising in an African American magazine versus a “mainstream” magazine between 1950 and 1965, concluding that “Blacks were subject first to less and then to more advertising than [W]hites.”200(p56) A similar content analysis of NNPA newspapers would be useful in appraising the extent to which Black newspapers supported the tobacco industry.

It would also be inappropriate to suggest that editorial support for tobacco industry positions “caused” today's tobacco-related health disparities among African Americans. Establishing causal links between media messages, media consumption, and health behaviors is difficult, particularly because behaviors are also influenced by beliefs, norms, and intentions.20 However, a wide body of literature20,77,201–204 suggests that media coverage contributes to social understandings about tobacco. Media convey (or omit) information about health practices and disease risks and thus have important roles in shaping health practices within communities.205–207

The term “quid pro quo” as applied to the tobacco-NNPA relationship should have a simple meaning: money paid to NNPA papers in exchange for valuable advertising.136 However, the tobacco industry expected more than this equal exchange. Tobacco companies viewed their support of the Black press as buying its loyalty and securing its favor.150 This relationship represents a quid pro quo plus, that is, expecting a return of more than equal value.

As NNPA publishers were frequently reminded, tobacco companies bought ads when few other companies would do so74,75,189; thus, the NNPA was still paying its “debt” to the industry decades later. The NNPA, in turn, was apparently convinced that it warranted special treatment from tobacco companies and demanded advertising support after it supported tobacco industry issues. This support continued even amid emerging pressure from African American health advocates who challenged tobacco industry targeting of minorities. The “threatening”167(p1) stance taken by publishers when tobacco advertising budgets dropped in the 1990s suggests that publishers were beginning to realize how their allegiance was being taken for granted.

The Code of Journalistic Ethics holds that journalists should “deny favored treatment to advertisers and special interests.”208 The quid pro quo between tobacco companies and the NNPA violated this standard, which was officially adopted by the Society of Professional Journalists in 1996 (and which had existed in a different form since 1926).208 Yet 2 years later, NNPA president Leavell asserted, “Tobacco ads influence us.”186 As advertisers, the tobacco companies sought and received favored treatment; publishers justified their position by claiming that they could not survive without tobacco advertising.186

But this position did not merely violate an abstract principle. Ethnic media, and African American media in particular, have a “triple role—reinforcing ethnic identity, transmitting culture, and facilitating advocacy and political participation.”27(p213) As a Black press historian said, “The black press was never intended to be objective… . It often took a position… . This was a press of advocacy.”25 If African American readers across the decades of the last century assumed that the Black press advocated positions on their behalf, then the quid pro quo we have described takes on new significance. NNPA newspaper readers likely expected that publishers had their best interests at heart and assumed that they conveyed complete, accurate information about tobacco's harmfulness and about public policy measures to reduce it. These publications’ apparent prioritization of serving the tobacco industry over safeguarding their readers’ health suggests that they may not have fully appreciated the extensive harm that tobacco caused the Black community. The NNPA-tobacco alliance was understandable in earlier decades, when advertisers were fewer, evidence of tobacco's harmfulness to health was unclear, and the industry was actively working to further the “controversy” idea. But the alliance continued even as the evidence became irrefutable and African American communities began resisting tobacco marketing and industry overtures.

Limitations

Additional relevant documents may exist that we could not locate. The LTDL is limited by the legal discovery process (i.e., it is unlikely that states’ plaintiffs specifically requested all NNPA-related materials), and we did not have access to the full NNPA archives. We had limited access to more recent materials. We focused on the NNPA because it represents a significant share of African American media, but other groups (and other media, such as radio70) also influence information dissemination in African American communities. It was beyond the scope of this study to fully examine NNPA publications for content, so we cannot draw quantitative conclusions about the extent of newspaper support for industry positions.

Conclusions

Today's tobacco-related health disparities among African Americans1–4 result from numerous intertwined factors. Historic racial oppression surely contributed to the NNPA's willingness to continue to serve industry interests because it feared losing the Black press's voice without tobacco money. Yet, this does not seem to fully explain the continuing ties still linking many African American leadership organizations to tobacco industry patronage.209–214 Recently, a Wall Street Journal article described how an African American public relations consultant and founding member of the National Association of Black Journalists pitched an editorial opposing a menthol cigarette ban on behalf of the firm's client, Lorillard tobacco company (maker of the leading menthol brand).215 Progressive African American leaders have called for a reevaluation of these relationships. The quid pro quo some organizations still sustain with tobacco companies is the legacy of an inequitable trade that has contributed to incalculable harm to African American communities.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health (grant 5R25 CA 113710-03A2), the National Cancer Institute (grant R01 CA120138), the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (grant 9RT-0095), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse San Francisco Treatment Research Center (grant P50 DA009253).

We acknowledge the data-retrieval assistance of Vera Harrell and Antwi Akom.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this research.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Adult cigarette smoking in the United States: current estimates. Updated September 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm. Accessed October 13, 2009

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services Vital and Health Statistics. Report no. 242 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services Tobacco Use Among US Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moolchan ET, Fagan P, Fernander AF, et al. Addressing tobacco-related health disparities. Addiction. 2007;102(suppl 2):30–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention QuickStats, percentage of US adults aged ≥18 years who are current smokers, by age group and race/ethnicity—National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2006–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(15):405 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5815a10.htm. Accessed June 10, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delva J, Tellez M, Finlayson TL, et al. Cigarette smoking among low-income African Americans: a serious public health problem. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(3):218–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(suppl 4):10–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Headen SW, Robinson RG. Tobacco: from slavery to addiction. : Braithwaite RL, Taylor SE, Health Issues in the Black Community. 2nd ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001: xxxvi, 609 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson RG, Sutton CD, James DA, Orleans CT. Pathways to Freedom: Winning the Fight Against Tobacco. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Surveillance for cancers associated with tobacco use—United States, 1999–2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(SS08):1–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards BK, Brown ML, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(19):1407–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Heart Association Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update. Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/123783441267009Heart%20and%20Stroke%20Update.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2009

- 13.Max W, Sung HY, Tucker LY, Stark B. The disproportionate cost of smoking for African Americans in California. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):152–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence of cigarette use among 14 racial/ethnic populations—United States, 1999–2001. MMWR Weekly. 2004;53(3):49–52 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5303a2.htm. Accessed June 10, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yerger VB, Malone RE. African American leadership groups: smoking with the enemy. Tob Control. 2002;11(4):336–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton CD. Tobacco companies: targeting the African American community. Available at: http://www.determinedtoquit.com/howtoquit/methodsofquitting/faithbasedmethods/ltnmaterials/TargetAAmericanCommunity.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2010

- 17.Todt R. Tobacco firms said to target Blacks. November 2, 1998. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2501985348/5349. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/usa42d00. Accessed December 7, 2009

- 18.Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EMRJ. Reynolds’ targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):822–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muggli ME, Hurt RD, Becker LB. Turning free speech into corporate speech: Philip Morris’ efforts to influence US and European journalists regarding the US EPA report on secondhand smoke. Prev Med. 2004;39(3):568–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis RM. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and HumanServices, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballin S, Blum A, Burns D, et al. Tobacco use: an American crisis final conference report and recommendations from America's health community Washington, DC 930109–930112. January 12, 1993. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2070053568/3596. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pzm28d00. Accessed August 24, 2009

- 22.LaVeist TA. Minority Populations and Health: An Introduction to Health Disparities in the United States. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Introduction to African American colonial life: the Colonial Williamsburg official history site. 2011. Available at: http://www.history.org/almanack/people/african/aaintro.cfm. Accessed January 20, 2011

- 24.Armistead SP, Wilson CC., II A History of the Black Press. Washington, DC: Howard University Press; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson S. The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords [DVD]. San Francisco, CA: California Newsreel; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson CC., II Black press history: overview of the past 182 years of the Black press. Available at: http://www.nnpa.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=15&Itemid=44. Accessed October 21, 2009

- 27.Viswanath K, Lee KK. Ethnic media. : Waters MC, Ueda R, Marrow HB, The New Americans: A Guide to Immigration Since 1965. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2007:202–213 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver J. The Black press. Looking to the future. August 18, 1999. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2080829686. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zxq20c00. Accessed October 9, 2009

- 29.1. Question: Why do you use the Black press as a part of your advertising strategy? 1981. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 501797519/7524. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/anb55a00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 30. Chronology of Philip Morris policy of equal opportunity and involvement in the Black community first draft - 871224. December 24, 1987. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2021199107/9119. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kyc42d00. Accessed February 17, 2010

- 31.Brown GF. Philip Morris’ human relations program sets pace for industry. October 17, 1953. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2041942541/2544. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nqe45d00. Accessed September 25, 2009

- 32.Capparell S. The Real Pepsi Challenge: The Inspirational Story of Breaking the Color Barrier in American Business. New York, NY: Wall Street Journal Books; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Northrup H, Ash R. The Racial Policies of American Industry: The Negro in the Tobacco Industry. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School of Finance and Commerce, Department of Industry, Industrial Research Unit; 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lochlann Jain SS. “Come up to the Kool taste”: African American upward mobility and the semiotics of smoking menthols. Public Cult. 2003;15(2):295–322 [Google Scholar]

- 35.NNPA member papers. Available at: http://www.nnpa.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=16&Itemid=45. Accessed February 25, 2010.

- 36.Caburnay CA, Kreuter MW, Cameron G, et al. Black newspapers as a tool for cancer education in African American communities. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):488–495 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Ethnic Media in America: The Giant Hidden in Plain Sight. San Francisco, CA: New California Media; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pew Research Center A year after Obama's election: Blacks upbeat about Black progress, prospects. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2010. Available at: http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1459/year-after-obama-election-black-public-opinion. Accessed June 10, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Association of Attorneys General Master Settlement Agreement. 1998. Available at: http://www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa/msa-pdf. Accessed June 10, 2011

- 40.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9(3):334–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:267–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandt AM. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodlett CB. NNPA Russwurm pilgrimage program. March 12–13, 1965. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 41. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 44. Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969, 15 USC §1335 (2010).

- 45. East St Louis Crusader. Cigarette company to double Black ads. February 7, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726463. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nlv61d00. Accessed August 3, 2009

- 46.Indianapolis Recorder. Salem to double ads in Black press. February 9, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726484. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/slv61d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 47. Birmingham World. NNPA editors and publishers receive Salem advertising. February 9, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726465. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/olv61d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 48.Mississippi Enterprise. NNPA Midwinter Session. February 9, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726473. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/plv61d00. Accessed Augsut 21, 2009

- 49.Gary, Indiana Crusader. R. J Reynolds announces increased advertising plans at NNPA confab. February 9, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726475. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qlv61d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 50.Salem will double ads with Black press February 9, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726480. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dmk10d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 51.Indianapolis Recorder. NNPA midwinter session. February 9, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726483. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/emk10d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 52. Carolina Peacemaker. Black editors and publishers told of Salem ad increase. February 16, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726485. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tlv61d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 53.Louisville Defender. Salem will double advertising in Black newspapers. February 14, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726486/6487. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ulv61d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 54.Wilmington Journal. Salem will double ads with Black press. February 9, 1974. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 500726478. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rlv61d00. Accessed November 13, 2009

- 55.Marcus R. Ogilvy & Mather public affairs. December 22, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034270. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pxw32f00. Accessed March 5, 2010

- 56.Dymally MM. Jackson Advocate. Look who would carry the burden…again. October 15, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034272. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rxw32f00. Accessed March 8, 2010

- 57.Dymally MM. Ft. Lauderdale Gazette. Look who would carry the burden…again. October 18, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034274. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uxw32f00. Accessed March 8, 2010

- 58.Dymally MM. Arizona Informant. Look who would carry the burden.again. September 30, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034276. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wxw32f00. Accessed March 8, 2010

- 59.Dymally MM. Iredell County News. Excise tax is ill-advised solution for woes. October 29, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034275. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vxw32f00. Accessed March 8, 2010

- 60.Dymally MM. Philadelphia New Observer. Look who would carry the burden…again. November 4, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034271. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qxw32f00. Accessed March 8, 2010

- 61.Dymally MM. Omaha Star. Look who would carry the burden…again. October 8, 1987. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TITX0034273. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sxw32f00. Accessed March 8, 2010

- 62.Poole S.M. Atlanta Journal Constitution. Sullivan urges black publications to snuff out reliance on tobacco ads. May 18, 1991. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 513887342. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ndp30d00 Accessed October 8, 2009

- 63.Rhoads & Sinon LLP Model letter to RJ Reynolds in support of the coalition to stop the marketing of “Uptown” cigarette to the African American community of Philadelphia. January 19, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507607025. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eos28c00. Accessed December 4, 2009

- 64.Payne MT. Revised Uptown planning. January 12, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507745368/5370. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/oxj10d00. Accessed December 7, 2009

- 65.Brown J, Robinson RG, Allison Y, Mansfield C. Coalition Against Uptown Cigarettes. Speaking on behalf of the Coalition Against Uptown Cigarettes in Philadelphia's African American community. January 22, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507777179/7180. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vfq14d00. Accessed December 7, 2009

- 66.Jackson WG. Attached. May 7, 1990. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2025426523. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rfo04e00. Accessed August 25, 2009

- 67.Brown v. Board of Educ, 347 US 483, 495 (1954).

- 68.US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. Washington, DC: Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 1964 [Google Scholar]

- 69. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, 111th Cong, 1st Sess (2009).

- 70.Newman KM. The forgotten fifteen million: Black radio, the “Negro market” and the civil rights movement. Radic Hist Rev. 2000;76:115–135 [Google Scholar]

- 71.JRH Marketing Services Summary report of qualitative research on corporate image advertising among African-American opinion leaders. May 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507712740/2759. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dux14d00. Accessed October 26, 2009

- 72.Klan chief urges boycott of 3 firms for NAACP aid October 1956. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2041942549. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rqe45d00. Accessed September 25, 2009

- 73.Sales of Philip Morris cigarettes drop 48 percent October 1956. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2041942546/2547. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pqe45d00. Accessed September 25, 2009

- 74.Millhiser RR, Frank E. Resnik remarks Black newspaper publishers 851115 9 00 A.M. November 15, 1985. Philip Morris. Bates no. 1002353062/3075. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/grf48e00. Accessed December 2, 2009

- 75.Powell G. November 15, 1985. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2023645326/5329. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hsx88e00. Accessed July 29, 2009

- 76. US Exhibit 77,557, advertisement, “Statement of formation of TIRC and advertising schedule” TOBACCO INDUSTRY RESEARCH COMMITTEE, January 4, 1954. January 4, 1954. DATTA. Bates no. USX3631976/USX54. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsx36b00. Accessed September 16, 2009

- 77.Cummings KM, Morley CP, Hyland A. Failed promises of the cigarette industry and its effect on consumer misperceptions about the health risks of smoking. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 1):i110–i117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tobacco Industry Research Committee A frank statement to cigarette smokers. 1954. Council for Tobacco Research. Bates no. 11309817. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hld6aa00. Accessed May 21, 2010

- 79.Glantz SA. The Cigarette Papers. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fuller & Smith & Ross Inc A report to the Tobacco Industry Research Committee. January 15, 1954. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. CORTI0010275/0314. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/obj30c00. Accessed August 24, 2009

- 81.Bowling JC. January 6, 1954. Philip Morris. Bates no. 1005039784. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zae74e00. Accessed August 24, 2009

- 82.Cameron Rw. D. Parke Gibson Associates Inc. Selections of Negro assemblies in which participation by R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company would be most beneficial. September 5, 1968. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 513338433/8435. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fyb27a00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 83.National Newspaper Publishers Association 31st annual convention. June 16–19, 1971. William O. Walker Papers, Box 197-8, Folder 22. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 84.National Newspaper Publishers Association (the Black press of America) board meeting. September 8–9, 1972-Baltimore Hilton. September 8–9, 1972. William O. Walker Papers, Box 197-8, Folder 11. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 85.Bass MB.Confirmation for the NNPA annual awards banquet on Friday, June 21, at the Westin Hotel in Seattle. April 9, 1985. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 505475284. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lyr15d00. Accessed October 16, 2009.

- 86.Bass M. Remarks by Marshall Bass. June 19, 1987. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507752146/2158. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rdt14d00. Accessed August 3, 2009

- 87.Stanley KT. August 13, 1973. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 37. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 88.Briscoe S. July 5, 1973. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 37. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 89.Bass MB. March 7, 1974. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 22. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 90.Goodlett CB. June 28, 1975. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 5, Folder 2. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 91.Stanley KT. August 13, 1975. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 37. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 92.Minutes of the meeting of NNPA board of directors held September 9–10, 1977. September 9–10, 1977. William O. Walker Papers, Box 197-8, Folder 11. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 93.Stanley KT. December 21, 1977. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 36. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 94.Goodlett CB. January 3, 1977. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 5, Folder 4. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 95.Goodlett CB. June 6, 1978. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 5, Folder 5. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 96. The 1972 NNPA awards. 1972. William O. Walker Papers, Box 197-8, Folder 5. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 97.Briscoe S. May 5, 1975. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 37. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 98.Rowe WL. April 12, 1976. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 35. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 99.Rowe WL. June 1, 1976. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 34. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 100.Briscoe S. March 17, 1978. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 36. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 101. NNPA 39th annual convention. June 13–16, 1979. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 38. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 102.Kirk RM. Minority marketing a continuing challenge. May 22, 1979. Brown & Williamson. Bates no. 690143962/3972. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xvg13f00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 103. NNPA 40th annual convention. June 18–21, 1980. William O. Walker Papers, Box 197-8, Folder 24. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 104. NNPA 41st annual convention. June 24–27, 1981. William O. Walker Papers, Box 197-8, Folder 25. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 105.Britt CL. October 8, 1976. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 36. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 106. TAI-Line: official publication of the Tuskegee Airmen Inc., post-convention edition. October, 1986. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI51401847/1854. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/phs98b00. Accessed December 21, 2009.

- 107.Scott SS. The Black Press as defender, voice, and guide. October 24, 1987. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2023645672/5693. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vgg45d00. Accessed August 24, 2009

- 108.Murphy J. Remarks by John Murphy National Newspaper Publishers Association 900629 Chicago, Illinois. June 29, 1990. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2023644429/4440. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ztx88e00. Accessed September 25, 2009

- 109.Moskowitz S. NNPA remarks. November 9, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507756110. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ptj01d00. Accessed October 7, 2009

- 110.Johnston JW. Jim Johnston remarks NNPA executive committee the Piedmont Club - Winston-Salem. November 12, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507756111/6132. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mqs14d00. Accessed October 7, 2009

- 111.Johnston JW, Singleton JW. Jim Johnston remarks. NNPA executive committee. The Piedmont Club Winston-Salem. November 12, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 513253557/3581. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gre23d00. Accessed October 7, 2009

- 112.Johnston JW. Remarks by James W. Johnston to the NNPA executive committee the Piedmont Club Winston-Salem, NC. November 12, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 508551753/1761. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mpg93d00. Accessed October 7, 2009

- 113.Johnston JW. Regression toward repression. Remarks by James W. Johnston chairman and CEO, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. to the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) executive committee. November 12, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 512027000/7013. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aah43d00. Accessed November 16, 2009

- 114.Outline Remarks by Jim Johnston to NNPA executive committee. November 12, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507756138/6139. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fwr56a00. Accessed October 7, 2009

- 115.Singleton JW. Press release. Winston-Salem, N.C.–R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. chairman and chief executive officer James W. Johnston lamented America's “regression toward repression” in recent remarks before the executive committee of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA). November 21, 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 512026988/6991. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xzg43d00. Accessed November 16, 2009.

- 116.Singleton JW. Outline for NNPA speech. January 7, 1991. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507767980. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qvv28c00. Accessed October 19, 2009

- 117.Ruffin BS. Outline. Remarks by Ben Ruffin. NNPA mid-winter conference, January 16–20. January 7, 1991. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507767981/7986. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pvv28c00. Accessed October 8, 2009

- 118. Remarks of Ellen Merlo vice president, marketing, Philip Morris USA At the convention of the National Newspaper Association. June 24, 1998. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2063541391/1402. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ekl67d00. Accessed October 8, 2009

- 119. NNPA presentation - 980121 Montego Bay, Jamaica. January 21, 1998. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2073203846/3855. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pkl95c00. Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 120.Carney AL., Jr Facsimile transmission NNPA presentation. January 13, 1998. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2082316902. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fmn49c00. Accessed October 20, 2009

- 121. NNPA presentation - 980121 Montago Bay, Jamaica. January 21, 1998. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2082316903/6911. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kmn49c00. Accessed October 20, 2009.

- 122.Goldstone SF. Remarks of Steven F. Goldstone. Chairman and CEO, RJR Nabisco to the National Newspaper Publishers Association. June 19, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 520421400/1405. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/awx31d00. Accessed October 8, 2009

- 123.Goldstone SF. Remarks of Steven F. Goldstone, chairman and CEO, RJR Nabisco to the National Newspaper Publishers Association June 19, 1998 (19980619) Memphis, Tennessee. June 19, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 530525631/5639. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/phf65a00. Accessed October 20, 2009

- 124.Goldstone SF. Remarks of Steven F. Goldstone chairman and CEO RJR Nabisco to the National Newspaper Publishers Association. November 23, 1999. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 522531696/1699. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aid50d00. Accessed October 9, 2009

- 125.Ruffin BS. Recent address to the National Newspaper Publishers Association at their annual in Memphis, Tennessee. July 15, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 520527273/7278. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xzq70d00. Accessed December 2, 2009

- 126.Ruffin BS. Additional attachment to draft letter for Mr. Steven F. Goldstone re NNPA convention–Memphis, Tennessee. July 16, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 520527279. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sqe60d00. Accessed December 2, 2009

- 127. We say it. We mean it. We print it. July 16, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 520527280. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yzq70d00. Accessed December 2, 2009.

- 128.Walls T. Remarks of Tina Walls vice president, external affairs Philip Morris Management Corp. National Newspaper Publishers Association annual summer conference Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture Harlem, New York. June 16, 1999. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2073203298/3300. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ijl95c00. Accessed March 23, 2010

- 129.Walls T. Remarks of Tina Walls, vice president, external affairs Philip Morris Management Corp. National Newspaper Publishers Association annual winter conference, Tempe, Arizona 990113. January 13, 1999. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2082023408/3409. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zbi86c00. Accessed March 29, 2010

- 130.Goodlett CB. July 21, 1973. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 4, Folder 13. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 131.Goodlett CB. September 24, 1979. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 5, Folder 6. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 132.Goodlett CB. September 6, 1980. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 5, Folder 7. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 133.Goodlett CB. December 14, 1981. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 5, Folder 8. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 134.Sticht JP. Four leading Black publishers from the National Newspaper Publishers Association will visit with us on May 22, 1979. May 14, 1979. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 501472252. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/evz39d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 135.The communications committee of the Tobacco Institute for the Tobacco Institute public relations division A Tobacco Institute interim communications plan addressing four high priority issues. November 15, 1983. Lorillard. Bates no. 03521195/1214. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ydc81e00. Accessed October 7, 2009

- 136.Black's Law Dictionary. 8th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Group; 2004:1282 [Google Scholar]

- 137.Smith GI. Philip Morris USA corporate affairs department strategy project update. January 21, 1985. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2021502348/2356. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/brs24e00. Accessed August 25, 2009

- 138.Browder A. Tobacco Institute. March 8, meeting with Thomas Johnson and Dr. William Lee. March 12, 1985. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI05911491/1497. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gfh69b00. Accessed January 19, 2010

- 139.Tobacco Institute The Tobacco Institute public affairs division proposed budget and operating plan. 1989. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI06060419/0529. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wqg69b00.Accessed January 19, 2010

- 140.Tobacco Institute Cigarette ad ban briefer. June 9, 1986. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI50410543/0575. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/muv20g00. Accessed January 19, 2010

- 141.National Newspaper Publishers Association 1986. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI51600991/0992. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kab93b00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 142. November 21, 1985. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TCAL0194902. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xwk19b00. Accessed December 21, 2009.

- 143.Osborne L. National Newspaper Publishers’ Black Press dinner. March 4, 1988. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI17720698. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/czd00g00. Accessed January 19, 2010

- 144.Stuntz S. March 8, 1988. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI17720697. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bzd00g00. Accessed January 19, 2010.

- 145. Another point of view. January 21, 1987. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2024272085. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ngp14e00. Accessed August 3, 2009.

- 146.Black Monitor. Is the tobacco industry–“a friend of Black America”–being unilaterally attacked? January 1988. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI07071125/1129. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lbw82b00.Accessed December 10, 2009

- 147a.Ogilvy & Mather. Update on Excise Taxes. October 2, 1987. Tobacco Institute Collection. Bates No. TITX0038160/8166. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lfy32f00. Accessed August 10, 2011

- 147b.Marcus R. Ogilvy & Mather public affairs. October 16, 1987. Bates No. TI50911194/1196. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zyg38b00. Accessed August 10, 2011

- 147c.Sparber P, Ross J, Stuntz S, et al. Public affairs progress report December 1987. January 28, 1988. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TIDN0018389/8431. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gyh91f00. Accessed October 5, 2009

- 148.Ransome SM. National Newspaper Publishers’ Association: 48th annual convention. June 30, 1988. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI01341421/1423. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qie82b00. Accessed October 7, 2009

- 149.Stuntz S. National Newspaper Publishers’ Association: 48th annual convention. June 30, 1988. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI01671586. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jes24b00. Accessed December 2, 2009

- 150.Daragan K. Writing. August 29, 1995. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2047028009C/8010. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lvf77d00. Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 151.Singleton JW. Draft 2 op-ed. Michael Suggs to NNPA. Federal government has no basis for tobacco industry lawsuit. October 13, 1999. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 531228213/8215. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dbx55a00. Accessed October 20, 2009.

- 152.Singleton JW. Draft 4 op-ed. Michael Suggs to NNPA. Federal government has no basis for tobacco industry lawsuit. October 14, 1999. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 531228221/8223. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bbx55a00. Accessed October 20, 2009.

- 153. “Reframing the debate” communications plan. September 1, 2000. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 525191589/1596. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jbl93a00. Accessed December 2, 2009.

- 154.Wisconsin Historical Society Carlton Benjamin Goodlett Papers, 1942–1967. Available at: http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi/f/findaid/findaid-idx?c=wiarchives;cc=wiarchives;view=text;rgn=main;didno=uw-whs-micr0430. Accessed March 3, 2010

- 155.Sun Reporter. A Tribute To Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett. May 17, 1981. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 24 Folder 1. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC.

- 156.Goodlett CB. July 10, 1981. Brown & Williamson. Bates no. 661046798/6801. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/otl60f00. Accessed August 21, 2009.

- 157.Neville TB. August 28, 1981. Brown & Williamson. Bates no. 661046797. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ntl60f00. Accessed August 21, 2009.

- 158.Goodlett CB. Advertising in Black newspapers. March 26, 1982. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2010055117/5119. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mob34e00. Accessed August 21, 2009.

- 159.Scott SS. April 5, 1982. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2010055116. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lob34e00. Accessed August 21, 2009.

- 160.Thompson JJ., Dr Goodlett's letter. April 12, 1982. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2040938031/8032. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vhb04e00. Accessed December 4, 2009.

- 161.Beck C. April 15, 1982. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2010055112/5113. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lje98e00. Accessed August 21, 2009.

- 162.Goodlett CB. July 5, 1984. Brown & Williamson. Bates no. 676027187/7189. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hji73f00. Accessed August 3, 2009.

- 163.Garth W, Rasheed FH. June 18, 1984. Brown & Williamson. Bates no. 676027186. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gji73f00. Accessed October 7, 2009.

- 164.Goodlett CB. June 2, 1986. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2073811580/1582. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/thm28d00. Accessed September 25, 2009.

- 165.Smith GI. Minority advertising request. December 16, 1987. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2025430711/0713. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tic42d00. Accessed August 25, 2009

- 166.Minority Affairs. 1991. Research. Bates no. 507767707/7712. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jmp76b00. Accessed February 19, 2010.

- 167.Merlo E. November 17, 1992. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2023962807/2808. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yem24e00. Accessed September 28, 2009.

- 168.McDaniel PA, Malone RE. The role of corporate credibility in legitimizing disease promotion. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):452–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Philip Morris companies - total domestic. 1988. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2046023176/3186. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ueb42d00. Accessed October 7, 2009.

- 170.Cummings-Marryshow K. Circulation Experti & NNPA. December 17, 1991. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2041619861/9862. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fyc86e00. Accessed August 25, 2009.

- 171.Knox GL. NNPA. April 14, 1993. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2046023174/3175. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/teb42d00. Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 172.Banks-McKenzie S. African American ROP advertising. November 2, 1992. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2041954155. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kqb66e00. Accessed August 25, 2009.

- 173.Merlo E. December 4, 1992. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2023962735. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gsc42d00. Accessed August 25, 2009.

- 174. Proactive public relations plan African-American & Hispanic Market. June 20, 1998. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2071783355/3359. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/umf08d00. Accessed October 8, 2009.

- 175. Speakers’ Bureau 2000 plan. 2000. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2083493800/3805. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sky55c00. Accessed March 29, 2010.

- 176.Kent DB. Scholarship roster 1977-78 R.J. Reynolds Industries, Inc. #3350-77. 1977. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 36. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 177.Stanley KT. Re: NNPA scholarship report. January 11, 1978. Carlton B. Goodlett Papers, Box 36. Located at: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center Manuscript Division, Howard University, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 178. RJR Nabisco scholarship program in journalism. Recipients.1988-89(880000-890000). 1989. R. J Reynolds. Bates no. 507767805/7807. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hoe27a00. Accessed February 19, 2010.

- 179.Lockhart P. Marable M. Call report. To provide status report on public relations/community affairs projects in progress. February 5, 1991. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 507768295/8297. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cvv28c00. Accessed February 19, 2010.

- 180. Recommendations for 1993(930000) community action corporate (RJRN) contributions. 1993. Research. Bates no. 511993955. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mqa86b00. Accessed February 19, 2010.

- 181. Community Affairs Department. Budget. Amount paid. April 3, 1995. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 518284136/4141. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fef60d00. Accessed February 19, 2010.

- 182. Items shipped to NNPA conference San Diego, California. January 9, 1992. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 512726912. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gce33d00. Accessed September 28, 2009.

- 183. PR weekly update 3/29/04 (20040329). March 29, 2004. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 550728051/8052. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/elq27a00. Accessed October 9, 2009.

- 184. Current special public relations programs. 1990. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 512722734/2745. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qge33d00. Accessed December 2, 2009.

- 185.Amalgamated Publishers Inc “API honors past NNPA presidents“ co-sponsors: Miller Brewing Co. and Ryder Systems, Inc. 1995. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2071514617/4618. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kyr97a00. Accessed September 25, 2009

- 186.Muwakkil S. Gambit Weekly. Black Lungs. June 22, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 521421048/1051. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gto51c00. Accessed March 23, 2010

- 187.Meier B. Data on tobacco show a strategy aimed at Blacks. New York Times. February 6, 1998:A1

- 188. News summary. February 6, 1998. Tobacco Institute. Bates no. TI38560617/0627. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wdf53b00. Accessed March 23, 2010.

- 189.Knox G. Remarks George Knox vice president, strategy and development Philip Morris Management Corp. Black History Month reception and unveiling of radio documentary series “The Black Press: Pleading Our Own Cause” Wednesday, 990210. February 10, 1999. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2078240491/0496. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qnr75c00. Accessed October 9, 2009

- 190.Robinson RG, Pertschuk M, Sutton C. Smoking and African Americans: spotlighting the effects of smoking and tobacco promotion in the African American community. : Samuels SE, Smith MD, Improving the Health of the Poor: Strategies for Prevention. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 1992:122–181 [Google Scholar]

- 191.Jackson PM. Important Dates for 1996(19960000). December 4, 1995. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 528800062/0067. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rdt65a00. Accessed December 2, 2009

- 192. Press release. Reynolds Tobacco hosts luncheon at NNPA conference; shares information on $246 billion tobacco settlement. June 12, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 522605791/5792. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bum50d00. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- 193. Press release. Reynolds Tobacco hosts luncheon at NNPA conference; shares information on $246 billion tobacco settlement. June 12, 1998. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 522605790. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aum50d00. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- 194.Reed W. National Newspaper Publishers Association. As you know events of the past year have pointed out the separate nature, culture and information systems of the various segments of American society. November 17, 1995. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 518274162. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/oov50d00. Accessed December 21, 2009

- 195.Leavell DR. On behalf of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) and its board of directors, I would like to take this opportunity to personally invite you to participate in our 1997 annual mid-winter conference. November 12, 1996. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 518283719/3721. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nxs01d00. Accessed November 16, 2009

- 196.Ruffin BS. Business expense voucher. Tenn. Leg Blk Caucus mtg, Rev. J. Brown mtg. and NNPA Black Press Week event. PA, TN, DC contributions. March 21, 1997. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 518284410/4416. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wef60d00. Accessed October 8, 2009

- 197.Suggs M. On behalf of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA)–the Black Press of America–we would like to invite your organization to become a sponsor of the annual NNPA mid-winter conference January 11-15 in Dallas, Texas at the Adams Mark Hotel. September 28, 2000. R. J. Reynolds. Bates no. 522918404/8405. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zwb60d00. Accessed August 21, 2009

- 198.An S, Bergen L. Advertiser pressure on daily newspapers: a survey of advertising sales executives. J Advert. 2007;36(2):111–21 [Google Scholar]

- 199.Lasica JD. Preserving old ethics in a new medium. American Journalism Review. Available at: http://www.ajr.org/article.asp?id=1787. Accessed January 20, 2011

- 200.Pollay RW, Lee JS, Carter-Whitney D. Separate, but not equal: racial segmentation in cigarette advertising. J Advert. 1992;21(1):45–57 [Google Scholar]

- 201.Clegg Smith K, Wakefield M, Edsall E. The good news about smoking: how do US newspapers cover tobacco issues? J Public Health Policy. 2006;27(2):166–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Wakefield M, Szczypka G, Terry-McElrath Y, et al. Mixed messages on tobacco: comparative exposure to public health, tobacco company- and pharmaceutical company-sponsored tobacco-related television campaigns in the United States, 1999–2003. Addiction. 2005;100(12):1875–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Asbridge M. Public place restrictions on smoking in Canada: assessing the role of the state, media, science and public health advocacy. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(1):13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Wenger LD, Malone RE, George A, Bero LA. Cigar magazines: using tobacco to sell a lifestyle. Tob Control. 2001;10(3):279–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Apollonio DE, Malone RE. Turning negative into positive: public health mass media campaigns and negative advertising. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(3):483–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 206.Smith EA, Offen N, Malone RE. Pictures worth a thousand words: noncommercial tobacco content in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual press. J Health Commun. 2006;11(7):635–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 207.Smith EA, Offen N, Malone RE. What makes an ad a cigarette ad? Commercial tobacco imagery in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual press. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(12):1086–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 208.Code of ethics Society of Professional Journalists Web site. Available at: http://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp. Accessed January 14, 2010

- 209.McGruder C. Tobacco's global ghettos: big tobacco targets the world's poor. June 30, 1997. Available at: http://www.corpwatch.org/article.php?id=3970. Accessed July 9, 2010

- 210.Goldmacher S. NAACP's Huffman assailed for tobacco, telecom payments. Capitol Weekly. Available at: http://capitolweekly.net/article.php?xid=wnom4qgqlxct6b. Accessed July 9, 2010

- 211.National African American Tobacco Prevention Network Web site. Available at: http://www.naatpn.org. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- 212.National Association of African Americans for Positive Imagery Web site. Available at: http://www.naaapi.org. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- 213.URSA Institute African American leaders call on tobacco industry to stop targeting their community. Medical News Today. Available at: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/123172.php. Published September 26, 2008. Accessed July 9, 2010

- 214. Blacks for Prop 86 Web site. Available at: http://www.blacksforprop86.org. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- 215.Kesmodel D. Lorillard fights to snuff menthol ban. Wall Street Journal. January 6, 2011:A1.