Abstract

This randomized parallel group clinical trial assessed whether combined antibacterial and fluoride therapy benefits the balance between caries pathological and protective factors. Eligible, enrolled adults (n = 231), with 1–7 baseline cavitated teeth, attending a dental school clinic were randomly assigned to a control or intervention group. Salivary mutans streptococci (MS), lactobacilli (LB), fluoride (F) level, and resulting caries risk status (low or high) assays were determined at baseline and every 6 months. After baseline, all cavitated teeth were restored. An examiner masked to group conducted caries exams at baseline and 2 years after completing restorations. The intervention group used fluoride dentifrice (1,100 ppm F as NaF), 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse based upon bacterial challenge (MS and LB), and 0.05% NaF rinse based upon salivary F. For the primary outcome, mean caries increment, no statistically significant difference was observed (24% difference between control and intervention groups, p = 0.101). However, the supplemental adjusted zero-inflated Poisson caries increment (change in DMFS) model showed the intervention group had a statistically significantly 24% lower mean than the control group (p = 0.020). Overall, caries risk reduced significantly in intervention versus control over 2 years (baseline adjusted generalized linear mixed models odds ratio, aOR = 3.45; 95% CI: 1.67, 7.13). Change in MS bacterial challenge differed significantly between groups (aOR = 6.70; 95% CI: 2.96, 15.13) but not for LB or F. Targeted antibacterial and fluoride therapy based on salivary microbial and fluoride levels favorably altered the balance between pathological and protective caries risk factors.

Key Words: Dental caries, Dentistry, Fluoride, Mutans streptococci, Oral health, Randomized clinical trial

Introduction

The overall objective of the study was to provide clinical evidence that scientifically based caries risk assessment with corresponding aggressive preventive measures and conservative restorations would result in reduced caries increment compared to adult dental care not using this combined approach. The hypothesis tested was that caries management and conservative restorative treatment based on caries risk status (low or high) would significantly reduce 2-year caries increment compared to traditional, non-risk-based dental treatment.

Recent extensive surveys of adults and children clearly show dental caries, although considerably reduced in prevalence and severity since the 1960s, continues to be a major health problem in the USA [Winn et al., 1996; Dye et al., 2007] and elsewhere; it remains the leading cause of tooth loss [Kaste et al., 1996]. Despite the major advances of water fluoridation and fluoride dentifrice use, a segment of the population remains at risk of caries progression in all age ranges [Chauncey et al., 1989].

The carious process is recognized as a balance between protective factors (fluoride, calcium, phosphate, saliva and antibacterial agents) and pathological factors (cariogenic bacteria, dietary habits – especially frequent ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates, and lack of saliva) [ten Cate and Featherstone, 1991; Featherstone, 2004]. Most caries now resides in 25–40% of the adult population [Macek et al., 2004]. Therefore, ideally, correctly assessing caries risk will lead to a therapeutic treatment regimen for effective management of dental caries [Klock et al., 1989; Leverett et al., 1993a, b; Bader et al., 2001, 2005]. With accurate risk assessment, noninvasive care modalities, including chlorhexidine antimicrobial and fluoride rinses [Luoma et al., 1978; O'Reilly and Featherstone, 1987; Billings et al., 1988; Krasse, 1988], can be applied with confidence and invasive restorative procedures (if needed) can be more conservative, preserving tooth structure and better benefiting patient oral health [Featherstone et al., 2003; Featherstone, 2004]. No practical caries risk assessment methodology has been proven in a controlled randomized clinical trial using a systematic caries management plan.

In the present controlled clinical trial a combination of salivary levels of mutans streptococci (MS, including Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus), lactobacilli (LB) and fluoride (F) was used to assess caries risk and thereby determine caries management. The overall study objective was to provide clinical evidence that the use of scientifically based caries risk assessment with aggressive preventive measures and conservative restorations will result in reduced 2-year caries increment compared to traditional care provided at the UCSF School of Dentistry during the trial.

Patients and Methods

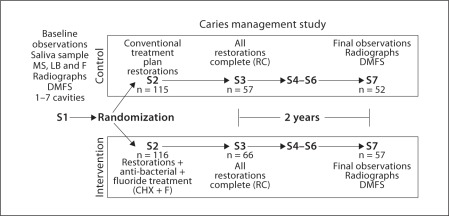

The overall study design is illustrated by the flow diagram in figure 1 and described in detail as follows.

Fig. 1.

Experimental flow diagram of subjects. Visit S1 was the baseline radiographic and clinical examination, S2 was the initiation of treatment, S3 was the restorations complete visit (RC), S4 through S6 were recalls at 6-month intervals and S7 was the final recall radiographic and clinical examination.

Subject Criteria and Screening

Before initiation, the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research (institutional review board) approved this study. New patients presenting to the School of Dentistry Student Dental Clinics for their first oral health examination were recruited to participate if they met eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria were: ability to speak and understand En glish, 18 years of age or older, planned to stay in the immediate area for the next 3 years, a minimum of 16 teeth, willing to have needed dental radiographs every 2 years, at least 1 and up to 7 cavitated carious teeth, no root caries, no moderate or severe periodontal disease needing periodontal surgery or chemotherapeutic agents, and voluntarily provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were significant past or current medical history of conditions that may affect oral health or oral flora (i.e., diabetes, HIV, heart conditions that require antibiotic prophylaxis), use of medications that may affect the oral flora or salivary flow (e.g., antibiotic use in the past 3 months, drugs associated with dry mouth/xerostomia), complex dental need, or frequent periodontal maintenance, another household member participating in the study, and drug or alcohol addiction, or other conditions that may decrease the likelihood of adhering to the study protocol.

Potential subjects were informed of the study by general announcements to the dental school provider community, posted signs, and newspaper advertisements. The study duration for each participant was approximately 3 years. Screening was open from August 29, 1999 through May 25, 2001. Enrollment was open from September 24, 1999 through June 1, 2001 and follow-up was from November 30, 2001 through July 7, 2004. Participants were followed for 2 years after all initially needed restorations were completed.

An independent dental examiner, who did not provide treatment, conducted the first round of clinical and radiographic exams to assess caries status [NIDR, 1991]. Paraffin-stimulated whole saliva samples were collected at that time to determine the bacterial challenge and fluoride level (F). The subjects were then randomized to control or intervention treatment (I) groups; randomization tends to balance measured as well as unmeasured baseline factors [Fleiss, 1999]. The saliva samples were analyzed for both groups to determine bacterial levels of MS, LB and total F. Overall risk status (table 1) was determined as low or high based on the bacterial challenge (combination of MS and LB) and F values (table 1). Cutoff levels for bacterial challenge were based on log10 MS (low <4, medium = 4–5.9 and high ≥6), and log10 LB (low <1, medium = 1–2.9 and high ≥3). Cutoff levels for F were low <0.03, medium = 0.03–0.079, and high ≥0.08 ppm. There is a general dearth of evidence for particular cutoff levels. We chose the bacterial challenge levels based upon previously published studies over several years by Krasse [1988] and the two published studies by Leverett et al. [1993a, b]. The fluoride levels used were those found in the studies by Leverett et al. [1993a, b] to be related to caries levels. Further, a subsequent 6-year clinical trial (unpublished by Featherstone and Billings) provided an additional data set that helped us to develop the caries risk tables.

Table 1.

Combinations of low and high caries risk and bacterial challenge as a function of log MS and log LB by three levels of salivary fluoride

| log LB, CFU/ml | log MS, CFU/ml |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| <4 | 4–5.9 | ≥6 | |

| Low fluoride [F] in saliva: [F] < 0.03 ppm | |||

| <1 | low risk | high risk | high risk |

| low challenge | medium challenge | high challenge | |

| 1–2.9 | high risk | high risk | high risk |

| medium challenge | medium challenge | high challenge | |

| ≥3 | high risk | high risk | high risk |

| medium challenge | high challenge | high challenge | |

| Medium fluoride [F] in saliva: 0.03 ppm ≤ [F] < 0.079 ppm | |||

| <1 | low risk | low risk | high risk |

| low challenge | low challenge | high challenge | |

| 1–2.9 | low risk | high risk | high risk |

| low challenge | medium challenge | high challenge | |

| ≥3 | high risk | high risk | high risk |

| medium challenge | high challenge | high challenge | |

| High fluoride [F] in saliva: [F] ≥ 0.08 ppm | |||

| <1 | low risk | low risk | high risk |

| low challenge | low challenge | high challenge | |

| 1–2.9 | low risk | low risk | high risk |

| low challenge | low challenge | high challenge | |

| ≥3 | low risk | high risk | high risk |

| low challenge | high challenge | high challenge | |

Randomization

A permuted block randomization with varying block size (4–16) stratifying on clinic day was generated (SG). The stratified list was provided to the clinical trial coordinator, who assigned participants in each stratum in sequential order to treatment group. Sequence was concealed from participants and clinical staff until assignment.

Blinding and Study Conduct

Due to the nature of the intervention, complete blinding/masking in this study was not possible. Neither participants nor clinicians could be blinded to study group, since placebo rinses were not employed. For the control group, study participants and their dental providers were blinded to assay results until study completion. The subjects in the control group received the usual standard of dental care provided in the UCSF predoctoral dental student clinics as if they were not part of a study. Control group subjects were asked not to inform their dental care providers about being in the study so they would be treated like other clinic patients. To limit information bias and to have the control group reflect the current standard of usual care this step was necessary.

For the intervention group, assay results were used to classify the participants into two categories based on their caries risk status. Dental providers of subjects in the intervention group were informed of assay and risk classification results. A specific dental care intervention regimen for each risk status category (see below) was implemented by providers specially trained to participate in this study.

At the completion of initial treatment for caries (defined as caries removal and restoration), a saliva sample was assayed from participants in both the intervention and control groups. Assay results for the intervention group were used to determine if the participants' risk category had changed. If the risk status remained high, additional intervention was provided.

All subjects were recalled at 6-monthly intervals for further saliva sampling after initial caries treatment was completed. The risk status in the intervention group determined whether further intervention was necessary. In the control group, there were no special encouragements for additional periodic oral exams, radiographs or dental prophylaxis. Further restorative treatment was conducted as usual, i.e., as providers deemed it necessary. This process continued for the entire study.

Two years after completion of initial restorative treatment, all subjects received a study recall appointment. Salivary assays were collected from all participants, prophylaxis provided, and dental examinations were conducted by the same independent, masked dental examiner (fig. 1). Participants were instructed not to tell the examiner their group assignment.

Measurement of Demographics

The existing clinic computerized patient electronic health record system and case report forms were used to record subjects' demographic variables of age, gender, race/ethnicity, county of residence, education, oral hygiene habits, oral health locus of control, insurance status, medical history, dental history, clinical diagnostic variables (caries diagnosis), treatment variables, explanatory variables (i.e. number of visits, time between visits), city and contact information.

Measurement of Clinical Variables

Saliva Collection Visits. Each subject provided a sample of whole paraffin-stimulated saliva at the commencement of the study (visit S1), after caries restorations were placed (visit S3) and every 6 months thereafter for the duration of their participation in the study (visits S4–S7, fig. 1). At visit S2, providers conducted a comprehensive oral examination and treatment plan. In addition, subject information was obtained by questionnaire at each saliva collection visit: changes in medical history, changes in (cariogenic) diet, medications taken since the last saliva collection (especially antibiotics, or those that may have affected salivary flow), changes in fluoride exposure (change in toothpaste, mouth rinse, residence, diet), dental treatment received outside of dental school, and any history of injuries to teeth.

Saliva Sampling Procedure. Whole stimulated saliva was collected for assessment of MS, LB and total F. Each subject chewed on two 1 × 1 inch squares of wax sheet (Parafilm) and 2–3 ml of saliva was expectorated into a prelabeled sterile 15-ml centrifuge tube. Saliva samples were chilled on ice for transport to the microbiology laboratory (5 min from the clinics).

Radiographic Examination. Conventional use of radiographs (bitewings and selected periapicals) were utilized for all subjects (control and intervention groups) at the beginning and end of the study, and as deemed necessary by the providers in the course of normal clinical treatment. Standardized dental radiographs were obtained using calibrated precision instruments by trained providers or qualified radiology technicians. According to accepted guidelines for radiographic assessment, this population was expected to have indicated bitewing radiographs every 24 months (beginning and end of the study).

Final Examination (Visit S7). Two years after each subject had completed his/her initial caries treatment a final independent, blinded exam was conducted by the same examiner who completed the initial baseline examination. Final caries status was assessed, an exit questionnaire administered, and a final saliva sample was taken for analysis.

Treatment Groups

Control (Conventional Treatment). Conventional dental care was provided by two control teams of dental students and their faculty dental providers. Participant treatment plans included plans for initial caries removal and restoration, and continued care needs for the duration of the study. After this initial caries restorative treatment was completed, the study coordinator scheduled the subject for a salivary assay. Dental care continued as usual in the clinic and no specific study-related recruitment for any procedures occurred with the exception of salivary assays. The subjects received a dental prophylaxis and needed radiographs at the end of the study. The prophylaxis, final radiographs and salivary assays were provided at no charge to the participants.

Intervention (Preventive Intervention Treatment). Intervention dental care was provided by two teams of dental students and their faculty dental providers. After randomization, clinicians were informed of the participant's caries risk status. Each subject received a treatment plan based on their high or low caries risk status as determined by the results of the assay. Frank cavitated carious lesions were restored. Radiographic interproximal lesions at least in the outer one third of the dentin with confirmed clinical cavitation were restored. Caries treatment was minimally invasive. Sealants were placed on unrestored occlusal surfaces that had incipient carious lesions or were likely to become carious.

High Caries Risk Intervention. These participants received a topical NaF gel application (1.1% NaF) during the clinic visit, counseling on reducing frequency of carbohydrate ingestion, the need for daily use of fluoride dentifrice, and the need for compliance. They were given a toothbrush and 1,100 ppm F (as sodium fluoride) toothpaste and instructed to brush daily at home. Subjects were prescribed a 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouth rinse to be used daily (1 min) for 2 weeks, to be repeated every 3 months. After the 2 weeks, another salivary assay was conducted to determine if the bacterial challenge had been reduced. If the bacterial challenge remained high an additional 2-week chlorhexidine treatment was prescribed. Subjects whose bacterial challenge remained high subsequently used the chlorhexidine rinse for the first 7 days of each month, instead of the 2 weeks every 3 months regimen. After completing the days of the chlorhexidine regimen, the participant was instructed to begin using a fluoride rinse (0.05% NaF) for 1 min daily until the next salivary assay. Participants were asked to use the rinses at night prior to going to sleep. If the salivary assay taken at the next visit indicated that the participant was at a lower risk, the subjects' intervention was altered to match their risk status.

Low Caries Risk Intervention. Subjects having low caries risk/low bacterial challenge did not receive chlorhexidine therapy. Subjects received counseling on reducing frequency of carbohydrate ingestion, the need for daily use of fluoride dentifrice, and the need for compliance. They were given a toothbrush and 1,100 ppm F (as sodium fluoride) toothpaste and instructed to brush daily at home.

Measures of Compliance

For both groups, records were kept of all missed and canceled appointments for dental treatment and collection of assays. Subjects in the intervention group using chlorhexidine and/or fluoride rinses were monitored by the study coordinator 1 week after the appointment (and regularly thereafter) and asked about compliance and arranged for subjects to obtain more antimicrobial and fluoride rinses as needed. The intervention participants were asked to keep a log of the days that they used each rinse, and to bring rinse bottles with them to the salivary assay collections so they could be refilled or replaced. The amount of rinse in the bottles was measured by the study coordinator.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the caries increment (change in number of decayed, missing and filled surfaces, ΔDMFS). Secondary outcome measures were (a) caries incidence and (b) changes in the number of decayed, missing or filled teeth, ΔDMFT, (c) changes in the number of decayed teeth, ΔDT, (d) changes in the number of decayed surfaces, ΔDS, (e) caries risk status, (f) MS and LB challenge, and (g) F levels.

Sample Size

Sample size to yield 90% power to detect a difference in the caries incidence between two proportions of 0.60 and 0.30 estimated that 122 subjects (61 in each treatment arm) were needed at the end of the study. Anticipating 20% attrition between enrollment and restoration complete and 30% attrition throughout the 2-year follow-up, the target sample size was increased accordingly. Power was anticipated to be greater for caries increment (ΔDMFS).

Data Analysis

The primary analyses used the intention-to-treat approach, using participants in the groups to which they were randomized to limit intentional and unintentional biases as well as to establish a basis for statistical analyses [Koch, 1988; Friedman, 1998]. A multivariable logistic regression model score test assessed the relationship of baseline variables with randomization group. Fisher's exact test compared retention at the final exam between the two randomization groups.

The primary treatment efficacy test planned was a minimal assumption nonparametric extended Mantel-Haenszel χ2 (EMH χ2) test comparing person-level 2-year caries increment of each treatment group adjusting for age (categorized by sample quantiles). However that test assumes missing data are missing completely at random [Molenberghs et al., 2004]. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) only assume data are missing at random [Molenberghs et al., 2004], so GLMM is an intention-to-treat method.

Changes in caries indices result in skewed distributions with many zeros, so zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) mixture models [Bohning et al., 1999] were used to assess non-negative changes in caries indices adjusting for baseline age and time between comprehensive oral examination and restoration complete (ΔDT and ΔDS were analyzed as –ΔDT and –ΔDS, since almost all participants had negative change scores; ΔDMFT, –ΔDT, and –ΔDS were analyzed with the few negative values recategorized as zero change for ZIP models). ZIP models tested a difference between intervention and control groups in caries index mean as well as a difference between intervention and control in proportion with no change in caries index (i.e. excess zeros). A GLMM with logit link and random person effects to compare randomized treatment groups in binary caries status over time with a time-by-group interaction was used as the primary efficacy test. To test changes in risk (low or high) and bacterial challenge levels (low, medium, or high) over time, logit or cumulative logit (proportional odds) GLMMs with random person effects (accounting for correlation within person over time) were used adjusting for baseline risk level; 95% confidence limits from GLMMs were estimated by bootstrapping the model predicted values (1,000 resamples). Predictor variables of overall risk, MS challenge, LB challenge and F levels were tested with these models. We adjusted for age and time between comprehensive oral examination and restoration complete as covariates in the GLMM and the Poisson portion of the ZIP models.

Results

The ratio of inquiries:subject enrolled was 10:1. The ratio of screened:enrolled was 4:1. The largest proportion of volunteers came from providers' direct recruitment efforts and local newspaper advertisements. A total of 231 subjects were enrolled in this study, 115 randomized to control and 116 to intervention group. Further, 52 (45%) subjects in the control group and 60 (52%) in the intervention group remained in the study through the 24-month follow-up period (Fisher's exact test p = 0.358). Three subjects in the intervention group at the final visit were sampled for saliva, but the clinical examination was not completed. The largest loss in follow-up occurred between S1 and S3 with subjects reporting their inability to pay for and complete their restorative treatment plans. Subject retention at each stage of the study (fig. 1) is tabulated in table 2.

Table 2.

Subject enrollment and retention at each stage in the clinical trial by treatment arm

| Baseline (S1) | RC (S3) | 6-month (S4) | 12-month (S5) | 18-month (S6) | 24-month (S7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 116 | 58 | 53 | 52 | 51 | 52 |

| Intervention | 115 | 66 | 60 | 58 | 57 | 60 |

| Total | 231 | 124 | 113 | 110 | 108 | 112 |

There was no statistically significant difference between control and intervention groups for baseline demographic, oral health-related behaviors and locus of control characteristics (score test χ2 = 67.1, 56 d.f., p = 0.148) (table 3, columns 2 and 3), which is consistent with randomization providing appropriate enrollment balance. Seventy-three percent of participants lived in optimally fluoridated San Francisco. Baseline characteristics between the groups for those seen at study completion are also shown in the table 3 (columns 4 and 5), demonstrating that the groups that were comparable at baseline following randomization remained comparable at the end of the study when the primary outcome measure was assessed. The model testing balance in baseline characteristics between these two groups for those who completed the study was nonsignificant (score test χ2 = 59.8, 55 d.f., p = 0.305).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics by treatment arm

| Baseline characteristic | All subjects |

Subjects who completed study |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control (n = 116) | intervention (n = 115) | control (n = 57) | intervention (n = 57) | |

| Age | ||||

|

38.4 | 36.9 | 40.9 | 39.2 |

|

13.5 | 13.2 | 14.8 | 14.7 |

|

18–84 | 18–77 | 20–84 | 21–77 |

| Gender: female, % (n) | 59 (69) | 60 (69) | 62 (32) | 67 (38) |

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | ||||

|

7 (8) | 13 (15) | 15 (8) | 25 (14) |

|

5 (6) | 7 (8) | 12 (6) | 14 (8) |

|

16 (18) | 24 (28) | 35 (18) | 47 (27) |

|

11 (13) | 6 (7) | 25 (13) | 11 (6) |

|

3 (4) | 2 (2) | 6 (3) | 2 (1) |

|

58 (67) | 48 (55) | 8 (4) | 2 (1) |

| Education, % (n) | ||||

|

22 (26) | 26 (30) | 19 (10) | 17 (10) |

|

56 (65) | 50 (58) | 50 (26) | 53 (30) |

|

22 (25) | 23 (27) | 31 (16) | 30 (17) |

| Works in San Francisco, % (n) | 69 (80) | 74 (85) | 81 (42) | 74 (42) |

| First UCSF S/D visit, % (n) | 41 (48) | 49 (56) | 56 (29) | 46 (26) |

| Last dental visit, % (n) | ||||

|

24 (27) | 28 (32) | 32 (16) | 29 (16) |

|

9 (10) | 20 (23) | 8 (4) | 18 (10) |

|

23 (26) | 18 (20) | 20 (10) | 16 (9) |

|

19 (22) | 12 (14) | 22 (11) | 13 (7) |

|

25 (29) | 22 (25) | 18 (9) | 23 (13) |

| Ever had professional cleaning, % (n) | 90 (98) | 91 (100) | 94 (46) | 89 (48) |

| Brushed 2+ times yesterday, % (n) | 77 (89) | 74 (85) | 77 (40) | 74 (42) |

| Used fluoride toothpaste, % (n) | ||||

|

76 (87) | 69 (79) | 75 (39) | 70 (40) |

|

18 (21) | 28 (32) | 18 (9) | 23 (13) |

| Used fluoride mouthrinse, % (n) | ||||

|

9 (10) | 9 (10) | 8 (4) | 9 (5) |

|

17 (19) | 23 (26) | 20 (10) | 22 (12) |

| Professional fluoride ≤1 year, % (n) | ||||

|

6 (7) | 14 (16) | 8 (4) | 12 (7) |

|

20 (23) | 12 (14) | 31 (16) | 10 (6) |

| Flossing frequency last week, % (n) | ||||

|

33 (38) | 27 (30) | 25 (13) | 27 (15) |

|

48 (55) | 48 (54) | 48 (25) | 46 (26) |

|

18 (21) | 26 (29) | 27 (14) | 27 (15) |

| Fair/poor oral health, % (n) | 53 (61) | 54 (62) | 42 (22) | 39 (22) |

| Fair/poor overall health, % (n) | 7 (8) | 15 (17) | 10 (5) | 16 (9) |

| Drank alcohol in past week, % (n) | 53 (61) | 50 (57) | 50 (25) | 47 (27) |

| Smoked cigarette ≤30 days, % (n) | 29 (34) | 27 (31) | 11 (6) | 14 (8) |

| Smoked cigar ≤30 days, % (n) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chewed/dipped tobacco ≤30 days, % (n) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Health locus of control, mean (SD) | ||||

|

4.6 (1.0) | 4.9 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.9) | 4.8 (0.8) |

|

2.1 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.3 (1.2) | 1.9 (0.9) |

|

3.1 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.1) |

|

5.3 (1.0) | 5.5 (0.8) | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.6 (0.7) |

| Number of teeth, mean (SD) | 25.7 (4.4) | 25.5 (4.9) | 25.4 (4.1) | 25.2 (5.1) |

UCSF S/D = University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry Student Dental Clinics.

With respect to toothbrushing there were 13 participants in the control group and 12 in the intervention group who reported changing toothpaste brands at a visit between S3 and S7 (some reported changing more than once). There were 6 participants in the control group and 10 in the intervention group who reported changing their toothbrushing frequency at a visit between S3 and S7. The number of participants who reported changes in toothbrushing were quite similar in each group.

Participants completing the study were significantly more likely than those who dropped out to work in San Francisco (Fisher's exact p = 0.012), be more educated (MH χ2 p = 0.014), have had a professional tooth cleaning more recently (MH χ2 p = 0.004), have better baseline self-rated oral health status (MH χ2 p < 0.001), and report less alcohol (MH χ2 p = 0.014) and tobacco use (MH χ2 p < 0.001); 25 other baseline variables were not significantly different.

There were no significant differences between control and intervention groups in baseline characteristics (table 3). The mean years between baseline and RC, baseline and final visit were not significantly different between intervention and control groups. Similarly, there were no significant differences in clinical characteristics in intervention and control at the baseline examination (table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of control and intervention groups at baseline and final examinations

| Clinical characteristic | Baseline |

Final |

Change (Δ) |

EMH χ2 p value | ZIP model p value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control (n = 116) |

intervention (n = 115) |

control(n = 52) |

intervention(n = 57) |

change in clinical characteristic | control (n = 52) |

intervention (n = 57) |

|||||||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | ||||

| DMFS | 30.3 | 22.5 | 30.2 | 25.0 | 34.4 | 21.2 | 31.0 | 25.0 | ΔDMFS | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.101 | 0.020 |

| DMFT | 11.7 | 5.4 | 11.5 | 6.0 | 12.5 | 4.5 | 11.7 | 5.4 | ΔDMFT | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.625 | 0.460 |

| DS | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1.4 | ΔDS | –2.2 | 3.4 | –2.6 | 3.1 | 0.422 | 0.136 |

| DT | 2.8 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.1 | ΔDT | –1.5 | 1.7 | –1.9 | 1.8 | 0.150 | 0.156 |

EMH χ2 is an extended Mantel-Haenszel test of the index values adjusted for baseline age quartiles. ZIP model is a zero-inflated Poisson mixture model of the indices adjusted for age and time between baseline comprehensive oral examination and restoration completion; for ΔDMFT the 5 people with negative changes were recategorized as having zero change, while for ΔDS and ΔDT, –ΔDS and –ΔDT were used with 5 and 3 people, respectively, recategorized as having zero change, since ZIP models require non-negative response variables.

Examiner reliability was measured with repeat observations. Repeat examinations (n = 33) showed excellent reliability [Lin's concordance DMFT 0.93 (95% CI; 0.971–0.995) and DMFS 0.996 (95% CI; 0.993–0.999)]. As the outcome variables were caries indices which are non-negative integers (discrete counts) measured at the participant level, a proper way to assess reliability for variables measured 2 times on such a scale is Lin's concordance correlation coefficient [Lin, 1989; Shoukri, 2010]. (Weighted) kappa statistics were not used since they are for nominally (or ordinally) scaled variables with the additional assumption that each entity categorized by a rater at the 2 times is independent of each other entity; having multiple tooth surface scores per person violates the independence assumption.

The mean (SE) number of years between baseline and restorations complete visits was 1.0 (0.07) and 1.0 (0.08) for control and intervention, respectively. The mean (SE) number of years between baseline and final visits was 2.8 (0.10) and 3.0 (0.10) for control and intervention, respectively.

The study coordinator recorded compliance based on returned intervention product for 54 of the 57 participants in the intervention group who had a final caries examination, rating 80% of them as being fully compliant and 20% partially compliant.

Clinical Outcomes

For the primary analysis, there were no significant differences in ΔDMFS, ΔDMFT, ΔDS, or ΔDT between control and intervention using the EMH test based upon the raw data. However, for all of these parameters the intervention group had lower (but not statistically significant) mean values than the control group.

Furthermore, the adjusted ZIP model of caries increment (change in DMFS) showed the intervention group had a statistically significantly lower Poisson mean than the control group [β (standard error, SE) = −0.234 (0.100), p = 0.020], but no difference in the probability of having no new DMFS (excess zeros) [β (SE) = −2.571 (0.577), p = 0.561] (table 4). In the mean (Poisson) portion of the ZIP model, neither covariate was statistically significant [age: β (SE) = 0.005 (0.003), p = 0.107; time until RC: β (SE) = −0.043 (0.087), p = 0.623]. The difference between the two groups in ΔDMFS corresponds to a statistically significant 24% reduction between intervention and control groups [(4.6–3.5)/4.6 = 0.24].

In the secondary analysis comparing caries incidence by the use of the Mantel-Haenszel test (p ≥ 0.324), there were no significant differences between intervention and control groups (table 5).

Table 5.

Two-year (post-RC) incidence of any new decayed, missing of filled teeth or surfaces by control and intervention groups

| Post-RC | Control (n = 52) | Intervention (n = 57) | EMH χ2 p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔDMFS >0 | 92% (48) | 88% (50) | 0.324 |

| ΔDMFT >0 | 54% (28) | 56% (32) | 0.918 |

| ΔDS >0 | 5.8% (3) | 3.5% (2) | 0.521 |

| ΔDT >0 | 3.8% (2) | 1.8% (1) | 0.438 |

EMH χ2 is an EMH test of the dichotomized index adjusted for baseline age quartiles.

All subjects had D >0 at baseline.

Caries Risk, Microbiology and Fluoride

Overall, the intervention significantly reduced caries risk category as compared to the control group over the study period from baseline through RC and each subsequent visit, before (table 6, OR = 3.25, p = 0.004) and after adjusting for baseline risk (aOR = 3.45, p = 0.001). There was a very strong significant difference in MS bacterial challenge between groups over time (OR = 6.60, p < 0.001; aOR = 6.70, p < 0.001) favoring the intervention group. There were no significant differences before or after adjusting for baseline in LB (p > 0.304) or F (p > 0.627) between intervention and control groups (table 6).

Table 6.

Group comparisons in relation to each of the four risks using logit random effects models (for the lower cutoffs); control vs. intervention from RC through each subsequent study visit over the 2-year follow-up period

| Risk type | Odds ratio (95% CI) (unadjusted)(n = 558 saliva samples for 123 participant visits) | Odds ratio (95% CI) adjusted for baseline risk (n = 558 saliva samples for 123 participant visits) | Odds ratio (95% CI) adjusted for baseline risk, age, and years between baseline and RC (n = 551 samples for 121 participant visits) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall risk (high) | 3.25 (1.48, 7.14)* | 3.45 (1.67, 7.13)* | 3.59 (1.74, 7.42)* |

| MS challenge (high) | 6.60 (2.77, 15.71)* | 6.70 (2.96, 15.13)* | 7.59 (3.37, 17.08)* |

| LB challenge (high) | 2.28 (0.47, 11.04) | 1.48 (0.55, 4.01) | 1.46 (0.55, 3.85) |

| FL level (low) | 1.11 (0.73, 1.70) | 1.05 (0.68, 1.61) | 0.98 (0.64, 1.50) |

p ≤ 0.05.

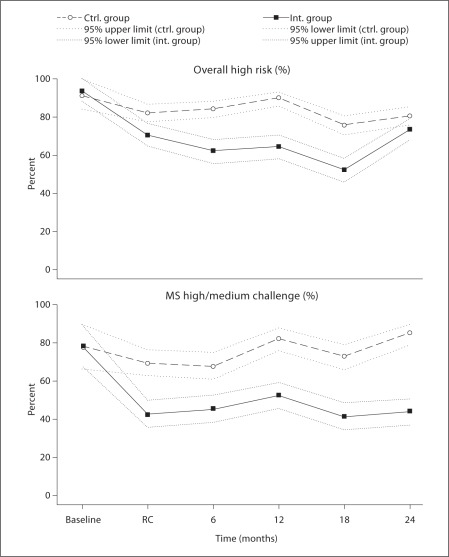

Figure 2 depicts the changes in the percent of subjects with (a) high caries risk, and (b) medium or high MS bacterial challenge from baseline through ‘restorations complete’ (RC) and the subsequent 24-month study period. At baseline, 91% of participants in the control group and 94% of those in the intervention group had high overall risk, while 77% of the control group and 78% of the intervention group had high or medium MS challenge. Placing restorations in the control group (baseline to RC) did not significantly reduce the MS bacterial challenge (fig. 2,lower panel), nor did placing restorations significantly change caries risk status in the control group (fig. 2, upper panel). However, intervention resulted in significantly lower percent of subjects at high risk and high/medium bacterial challenge during the period from baseline to RC (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Caries risk for control (ctrl.) and intervention (int.) groups as a function of bacterial challenge and time.

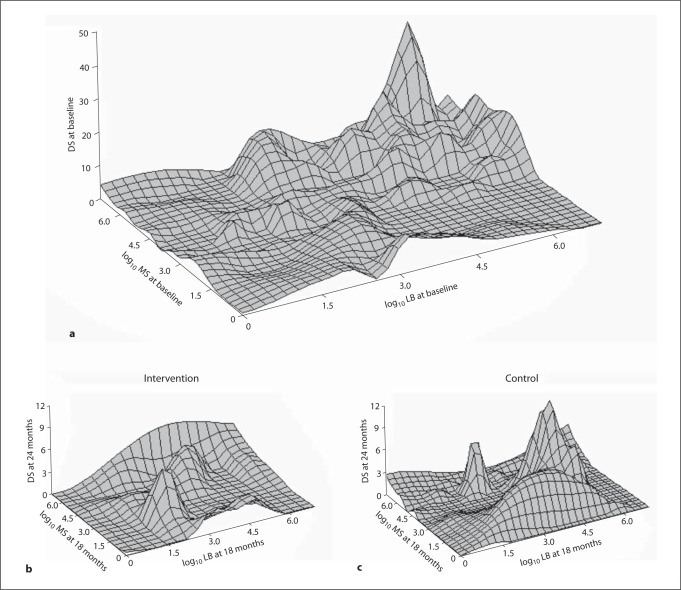

Three-dimensional plots (fig. 3) of log10 MS and log10 LB versus DS demonstrate a direct relationship between increased DS and medium/high MS and LB at baseline. The intervention and control three-dimensional plots at the conclusion of the study differ in shape, with control being similar to baseline. Both control and intervention groups had much lower DS at visit S7, the final visit (table 4, fig. 3), but there was no significant difference between the groups.

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional plots of MS, LB and DS at baseline (a) and 24 months in intervention (b) and control groups (c).

Discussion

Our primary hypothesis was that altering the caries balance by reducing pathological factors and enhancing protective factors, namely antimicrobial and fluoride rinses, would reduce caries risk and result in fewer carious lesions. The study was a randomized prospective clinical trial to test the efficacy of caries management by risk assessment. This study was not designed to test a particular product, but rather to determine whether the therapeutic management of dental caries based upon risk assessment (caries management by risk assessment) would lower caries increment. The results demonstrate that altering the pathological/preventive factor balance resulted in significantly lower caries risk and suggested reduced caries increment.

Our results are generalizable to adults with high caries risk. Because the subjects in our study came from our predoctoral clinics, they have a wide demographic, representative of the population receiving dental care. The study interventions and procedures were completed by students and faculty over a number of years, so there was a wide variation in clinicians, further increasing the generalizability of the results. It is conceivable that a few highly trained clinicians would have had even better results, but the generalizability would have suffered.

Having multiple student/faculty provider teams (control and intervention) over the course of the study may have led to two sources of bias. First, because control provider teams were in a dental school setting, they may have learned about caries management and recommended preventive interventions to their patients. Given that the study was conducted before changes in the curriculum regarding caries management occurred, it is unlikely that this was a large effect. The second bias may have been with the intervention group. Given that students graduate, multiple provider teams were used over the course of the study. Efforts to calibrate student and faculty providers in the intervention group may not have been as successful as we had planned, in comparison to a tightly controlled clinical trial with a smaller number of providers. The two sources of bias described would decrease the difference in caries increment between control and intervention groups and increase the generalizability of the study.

A further consideration is the relatively high dropout rate between baseline and restorations complete as shown in table 2. The number of dropouts was comparable between intervention and control groups. The reasons given were that the subjects could not afford to pay for the restorative treatment, even though they were made aware of this during the consenting process. However, they could not know specific costs until the regular dental examinations were completed in the clinics. The study paid for items and procedures related to the study but not for routine dental care needed by the patients. These dropouts resulted in lower than planned numbers in the study, even though we had allowed for larger than usual attrition. Retention after restorations complete was excellent in both groups.

Another limitation which is common to most long-term studies with humans is that we had to rely on participant self-reports of oral hygiene habits, which is subject to social desirability bias since most people know they should brush their teeth twice a day and floss every day and will report their habits as such even if they do not. However, we have no reason to believe that such a bias would be differential between the groups. Although the intervention group subjects were supplied with fluoride toothpaste and requested to brush daily we suspect that most did not change their habits. A small number in each group reported changing their toothpaste or frequency of use, however, the number of participants who reported changes in toothbrushing were quite similar in each group.

Compliance for the use of the rinses was assessed as described in the ‘Materials and Methods’ and ‘Results’ sections above and the use of the chlorhexidine rinse was manifested in major reductions in the levels of MS.

Most subjects in the study were high caries risk and high bacterial challenge. During the study, the intervention group had a significant overall reduction in MS bacterial challenge as compared to controls. Caries removal and restoration alone did not statistically significantly change bacterial challenge or caries or risk in either group. The use of an antimicrobial rinse, chlorhexidine, in conjunction with restoration, did reduce the bacterial challenge. The lack of a significant increase in mean salivary fluoride concentration in those subjects in the intervention group who were provided with the NaF rinse may indicate that they were not fully compliant with fluoride rinsing. It may be that the daily 0.05% sodium fluoride rinse was not a sufficient dose for this high caries risk population. The use of 5,000 ppm fluoride dentifrice twice a day or periodic fluoride varnish application may give greater protection, but were not tested in this study.

We expected that a reduction in overall risk and reduction of bacterial levels would be associated with lower numbers of decayed surfaces. The three-dimensional plots in figure 3 show that compared to baseline levels and controls, the intervention group at the final follow-up had lower bacterial levels of MS and LB and a trend towards lower DS, although not statistically significant (p = 0.14). Over the course of the study, the intervention group peak profiles changed to lower bacterial levels and lower peak height for decayed surfaces, whereas the control group profiles remained essentially unchanged from the baseline profiles. Looking at the clinical characteristics, there was a reduction in 3 of the 4 measures for the intervention group, change in DMFS, DT, and DS all were lower in the intervention than controls, although not significantly (EMH χ2). Further analyses used the adjusted ZIP model to test caries increment (change in DMFS). These analyses account for nonlinear distributions of caries indices. Our data had a large number of no change, zeros in the clinical characteristics, given the large number of tooth surfaces measured so a ZIP model analysis was justified. The data analyzed with this model showed that the intervention group had a statistically significantly lower mean than the control group (24%, p = 0.020). Although the study sample was recruited from the target clinic, the 2-year caries incidence was much lower than the historical clinic data, which reduced power to detect significant differences between the groups. Often research participants are healthier than nonparticipants or at least more interested in health promotion and disease prevention, so it is possible that study participants were more motivated to improve their oral health than nonparticipants. This study provides evidence that caries management by risk assessment is beneficial in altering the balance of protective and pathological factors. Caries management by risk assessment as a concept has continued to be adopted and implemented in dental practice [Domejean-Orliaguet et al., 2006; Featherstone et al., 2007; Jenson et al., 2007; Young et al., 2007].

We conclude that targeted antibacterial and fluoride therapy based on salivary microbial and fluoride levels favorably altered the balance between pathological and protective caries risk factors.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest with respect to this article.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH/NIDCR grant R01DE12455. In addition, Proctor and Gamble provided fluoride toothpaste, Omnii Oral Pharmaceuticals provided 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse (Peridex) and Oral B provided the 0.05% NaF rinse. The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The clinical coordinator for this study was Kim Tran with assistance from Rively Rodrigues and Jose Pelino. Nancy Cheng helped perform the GLMM analyses and created figure 2.

References

- Bader JD, Perrin NA, Maupome G, Rindal B, Rush WA. Validation of a simple approach to caries risk assessment. J Public Health Dent. 2005;65:76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2005.tb02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader JD, Shugars DA, Bonito AJ. A systematic review of selected caries prevention and management methods. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:399–411. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings RJ, Meyerowitz C, Featherstone JD, Espeland MA, Fu J, Cooper LF, Proskin HM. Retention of topical fluoride in the mouths of xerostomic subjects. Caries Res. 1988;22:306–310. doi: 10.1159/000261126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohning D, Dietz E, Schlattmann P, Mendonca L, Kirchner U. The zero-inflated Poisson model and the decayed, missing and filled teeth index in dental epidemiology. J R Statist Soc A. 1999;162:195–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chauncey HH, Glass RL, Alman JE. Dental caries. Principal cause of tooth extraction in a sample of US male adults. Caries Res. 1989;23:200–205. doi: 10.1159/000261178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domejean-Orliaguet S, Gansky SA, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment in an educational environment. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1346–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, Lewis BG, Barker LK, Thornton-Evans G, Eke PI, Beltran-Aguilar ED, Horowitz AM, Li CH. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Vital Health Stat. 2007;11:1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone JD. The caries balance: the basis for caries management by risk assessment. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2(suppl 1):259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone JD, Adair SM, Anderson MH, Berkowitz RJ, Bird WF, Crall JJ, Den Besten PK, Donly KJ, Glassman P, Milgrom P, Roth JR, Snow R, Stewart RE. Caries management by risk assessment: Consensus statement, April 2002. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:257–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone JD, Domejean-Orliaguet S, Jenson L, Wolff M, Young DA. Caries risk assessment in practice for age 6 through adult. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:703–707, 710–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Wiley Classics Library. New York: Wiley; 1999. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LM, Furberg CM, DeMets DL. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials. ed 3. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jenson L, Budenz AW, Featherstone JD, Ramos-Gomez FJ, Spolsky VW, Young DA. Clinical protocols for caries management by risk assessment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:714–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaste LM, Selwitz RH, Oldakowski RJ, Brunelle JA, Winn DM, Brown LJ. Coronal caries in the primary and permanent dentition of children and adolescents 1–17 years of age: United States, 1988–1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(special No):631–641. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klock B, Emilson CG, Lind SO, Gustavsdotter M, Olhede-Westerlund AM. Prediction of caries activity in children with today's low caries incidence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:285–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch GG, Edwards S. Clinical efficacy trials with categorical data. In: Peace KE, editor. Biopharmaceutical Statistics for Drug Development. New York: Dekker; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Krasse B. Biological factors as indicators of future caries. Int Dent J. 1988;38:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverett DH, Featherstone JD, Proskin HM, Adair SM, Eisenberg AD, Mundorff-Shrestha SA, Shields CP, Shaffer CL, Billings RJ. Caries risk assessment by a cross-sectional discrimination model. J Dent Res. 1993a;72:529–537. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720021001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverett DH, Proskin HM, Featherstone JD, Adair SM, Eisenberg AD, Mundorff-Shrestha SA, Shields CP, Shaffer CL, Billings RJ. Caries risk assessment in a longitudinal discrimination study. J Dent Res. 1993b;72:538–543. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720021101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989;45:255–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma H, Murtomaa H, Nuuja T, Nyman A, Nummikoski P, Ainamo J, Luoma AR. A simultaneous reduction of caries and gingivitis in a group of schoolchildren receiving chlorhexidine-fluoride applications: results after 2 years. Caries Res. 1978;12:290–298. doi: 10.1159/000260347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macek MD, Heller KE, Selwitz RH, Manz MC. Is 75 percent of dental caries really found in 25 percent of the population? J Public Health Dent. 2004;64:20–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs G, Thijs H, Jansen I, Beunckens C, Kenward MG, Mallinckrodt C, Carroll RJ. Analyzing incomplete longitudinal clinical trial data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:445–464. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/5.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDR . Diagnostic Criteria and Procedures. 91-2870. Bethesda: NIH; 1991. Oral Health Surveys of the National Institute of Dental Research. [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly MM, Featherstone JD. Demineralization and remineralization around orthodontic appliances: an in vivo study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;92:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoukri MM. Measures of Interobserver Agreement and Reliability. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ten Cate JM, Featherstone JD. Mechanistic aspects of the interactions between fluoride and dental enamel. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:283–296. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn DM, Brunelle JA, Selwitz RH, Kaste LM, Oldakowski RJ, Kingman A, Brown LJ. Coronal and root caries in the dentition of adults in the United States, 1988–1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(special No):642–651. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DA, Featherstone JD, Roth JR, Anderson M, Autio-Gold J, Christensen GJ, Fontana M, Kutsch VK, Peters MC, Simonsen RJ, Wolff MS. Caries management by risk assessment: implementation guidelines. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]