Abstract

Elevated sympathetic outflow and altered autonomic reflexes, including impaired baroreflex function, are common findings observed in hypertensive disorders. Although a growing body of evidence supports a contribution of preautonomic neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) to altered autonomic control during hypertension, the precise underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Here, we aimed to determine whether the intrinsic excitability and repetitive firing properties of preautonomic PVN neurons that innervate the nucleus tractus solitarii (PVN-NTS neurons) were altered in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). Moreover, given that exercise training is known to improve and/or correct autonomic deficits in hypertensive conditions, we evaluated whether exercise is an efficient behavioral approach to correct altered neuronal excitability in hypertensive rats. Patch-clamp recordings were obtained from retrogradely labeled PVN-NTS neurons in hypothalamic slices obtained from sedentary (S) and trained (T) Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) and SHR rats. Our results indicate an increased excitability of PVN-NTS neurons in SHR-S rats, reflected by an enhanced input-output function in response to depolarizing stimuli, a hyperpolarizing shift in Na+ spike threshold, and smaller hyperpolarizing afterpotentials. Importantly, we found exercise training in SHR rats to restore all these parameters back to those levels observed in WKY-S rats. In several cases, exercise evoked opposing effects in WKY-S rats compared with SHR-S rats, suggesting that exercise effects on PVN-NTS neurons are state dependent. Taken together, our results suggest that elevated preautonomic PVN-NTS neuronal excitability may contribute to altered autonomic control in SHR rats and that exercise training efficiently corrects these abnormalities.

Keywords: exercise, hypothalamic preautonomic neurons, nucleus tractus solitarii

elevated sympathetic outflow (Bergamaschi et al. 1995; Esler and Kaye 1998; Judy et al. 1976) and altered autonomic reflexes, including impaired baroreflex function (Grassi 2004; Judy and Farrell 1979) contribute to the development and maintenance of hypertensive disorders. Thus elucidating the mechanisms underlying altered autonomic control in hypertension is of critical importance.

The hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) is a major homeostatic center involved in the control of sympathetic outflow and regulation of blood pressure (Coote et al. 1998; Dampney et al. 2005; Swanson and Sawchenko 1983). PVN actions are mediated by preautonomic neurons that send descending projections to sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord (IML), as well as via projections to the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) and the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) (Armstrong et al. 1980; Saper et al. 1976; Swanson and Kuypers 1980) in the medulla. Whereas PVN-RVLM and PVN-IML pathways have been shown to mediate sympathoexcitatory responses (Allen 2002; Tagawa and Dampney 1999; Yang and Coote 1998), PVN-NTS projections have been implicated in PVN-mediated suppression of baroreflex function (Chen et al. 1996; Duan et al. 1999; Hwang et al. 1998; Jin and Rockhold 1989; Michelini 1994; Pan et al. 2007; Patel and Schmid 1988), as well as in heart rate adaptation during exercise training (Higa et al. 2002; Michelini and Stern 2009). Importantly, a growing body of evidence supports overactivation of preautonomic PVN neurons and their descending pathways as a major mechanism contributing to sympathoexcitation, altered reflex function, and elevated blood pressure in hypertensive disorders (Allen 2002; Earle et al. 1992; Li and Pan 2007b; Martin and Haywood 1998). Several mechanisms have been proposed to mediate elevated preautonomic PVN neuronal activity in hypertension, including a shift in the balance of inhibitory/excitatory synaptic transmitters (Biancardi et al. 2010; Li and Pan 2007a, 2007b; Osborn et al. 2007), as well as changes in intrinsic conductances, including altered K+ and Ca2+ channel function (Chen et al. 2010; Sonner et al. 2008, 2011). For the most part, however, these studies focused on PVN-RVLM and PVN-IML neurons. Thus, whether the excitability and/or activity of PVN-NTS neurons is also elevated in hypertensive rats, as a potential mechanism underlying altered baroreflex function in this condition, is presently unknown.

It is now widely recognized that physical activity reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, promoting several beneficial cardiovascular adjustments, including remodeling of the heart and skeletal muscle circulation (Amaral et al. 2000; Melo et al. 2003) and improvement of autonomic control of the heart (Clausen 1977; Negrao et al. 1993). Importantly, exercise has been shown to improve and/or correct deficits associated with hypertension, in both humans and animal models, including diminished sympathetic activity and pressure (Amaral et al. 2000; Collins et al. 2000; Melo et al. 2003), improvement of vagal outflow, as well as baroreflex function (Brum et al. 2000; Pan et al. 2007).

Our knowledge on the central mechanisms underlying beneficial effects of the exercise on autonomic control, particularly during hypertension, is, however, limited (see reviews of Waldrop et al, 1996; Potts, 2006; Raven et al, 2006; Michelini, 2007a, 2007b). Recent studies from our laboratories support the PVN as a likely brain region target mediating cardiovascular and autonomic effects of exercise. In this sense, we found exercise training to induce robust anatomical and functional plasticity within the PVN, including reorganization of afferent noradrenergic pathways, structural remodeling of dendritic trees, increased expression of peptidergic mRNA, and changes in intrinsic neuronal excitability (Higa-Taniguchi et al. 2007; Jackson et al. 2005; Martins et al. 2005; Michelini and Stern 2009); we proposed these actions to contribute to beneficial adaptive cardiovascular responses to exercise activity in normal rats (see Michelini and Stern 2009 for review). In addition, we found exercise to diminish noradrenergic inputs to the PVN in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (Higa-Taniguchi et al. 2007) and to partially correct a deficit in PVN and NTS oxytocinergic system in SHR rats (Martins et al. 2005). However, whether exercise training also affects and/or corrects altered neuronal excitability of preautonomic PVN neurons in hypertensive conditions is presently unknown.

On the basis of all this evidence, we aimed in the present study to determine 1) whether the intrinsic excitability of PVN-NTS neurons is altered in SHR rats and 2) whether exercise training is an efficient approach to correct altered excitability in this important cardiovascular-associated pathway. To this end, patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings were obtained from retrogradely labeled PVN-NTS neurons in four experimental groups: normotensive Wistar-Kyoto sedentary (WKY-S), WKY trained (WKY-T), SHR sedentary (SHR-S), and SHR trained (SHR-T) rats. A detailed analysis of basic membrane properties, single action potential waveforms, and repetitive firing properties were obtained from PVN-NTS neurons in these experimental groups. Overall, our results indicate an increased excitability of PVN-NTS neurons in SHR-S rats, mostly reflected by an enhanced input-output function in response to depolarizing stimuli. Moreover, we found exercise training to restore the elevated PVN-NTS firing discharge during repetitive stimulation back to those levels observed in normotensive WKY rats. The potential mechanisms underlying these effects are discussed in detail.

METHODS

Animals and exercise training protocols.

All protocols and surgical procedures used were approved by the Georgia Health Sciences University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Two-month-old male WKY and SHR rats, both based on a Wistar strain background (Harlan Laboratories), were housed in Plexiglas cages on a 12:12-h light-dark schedule and allowed free access to food and water. Rats were preselected for their ability to walk on a treadmill (5–10 sessions, 0.3 up to 0.9 km/h, 0% grade, 10–15 min/day), and only active rats (16 WKY, 16 SHR) were used in this study. At week 0, before starting protocols, active rats were submitted to a maximal exercise test (graded exercise on the treadmill, starting at 0.3 km/h with increments of 0.3 km/h every 3 min up to exhaustion) to determine maximal individual exercise capacities and to assign rats with equivalent capability to trained (T) or sedentary (S) groups. Half of the rats in each group were submitted to low-intensity training performed twice a day (1 h each), 5 days/wk, over 6 wk, as previously described (Jackson et al. 2005). Briefly, exercise intensity was increased progressively by a combination of time and speed to attain 50–60% of maximal exercise capacity, as determined by the maximal exercise tests on the treadmill. Maximal exercise tests were repeated at the third and sixth weeks to adjust training intensity and to compare the efficacy of the training protocol, respectively. Rats allocated to the S protocol were kept sedentary for a similar period of time and handled every day. Systolic blood pressure was measured using the tail-cuff method (RTBP 2000; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) in conscious rats. Animals were restrained in a holder, and the nose cone was adjusted so that the animal was comfortable but not able to move freely. The holder used was able to automonitor a pre-setup temperature (36°C). Rats were allowed to acclimatize for 10 min before measurements were obtained (average of 10 measurements/rat). Blood pressure and body weight were measured weekly during S and T protocols. Mean systolic pressure values obtained in each group at the end of the training protocol are summarized in Fig. 1.

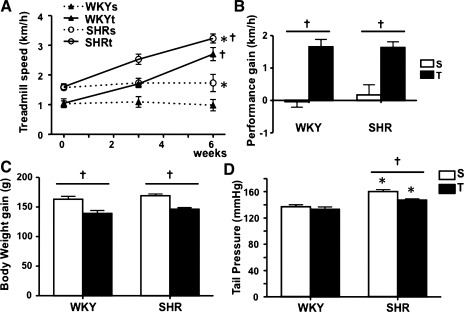

Fig. 1.

Efficacy of the exercise training protocol in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) and spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats. A: time course changes on treadmill performance in WKY and SHR groups submitted to sedentary (S) and training (T) protocols. B–D: comparison of performance gain (B), body weight gain (C), and tail pressure (D) in the 4 groups at the end of S and T protocols. Values are means ± SE; n = 8 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. WKY, †P < 0.05 vs. S.

Retrograde labeling of PVN-NTS projecting neurons.

At the end of the sixth week of the T protocol, rats from the four experimental groups (WKY-S, WKY-T, SHR-S, and SHR-T) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine-xylazine mixture (90 and 5 mg/kg, respectively), placed in a stereotaxic frame, and injected with a fluorescent retrograde tracer in the area of the NTS, as previously described (Li et al. 2003). The dorsal medulla was exposed after retraction of overlying muscles and occipital membranes. A small part of the occipital bone was removed to increase the exposure of the medulla. Rhodamine-labeled microspheres (Lumaflor, Naples, FL) were pressure-injected unilaterally (200 nl) into the NTS area at the level of the obex. The injection point was 1.0 mm lateral to the midline and 0.8 mm below the dorsal surface. After the injection, muscles were sutured together and the wound was closed. The location and extension of the injection sites were confirmed histologically. Injections in the NTS area were mostly restricted to caudal aspects of the NTS, although they also extended ventrally into the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (rostrocaudal extension: bregma −16.2 to −15.6) (see also Stern 2001).

Slice preparation.

Three days after the injection of the retrograde tracer, coronal hypothalamic slices (150–300 μm) containing the PVN were obtained for electrophysiological recordings using a vibroslicer (D.S.K. Microslicer; Ted Pella, Redding, CA), as previously described (Stern 2001). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip) and perfused through the heart with cold artificial cerebrospinal solution (aCSF) in which NaCl was replaced by an equiosmolar amount of sucrose, a procedure known to improve the viability of neurons in adult brain slices (Aghajanian and Rasmussen 1989). The standard aCSF solution contained (in mM) 120 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, and 0.4 ascorbic acid, pH 7.4 (297–300 mosmol/l). After the slicing procedure, hypothalamic slices were placed in a holding chamber containing standard oxygenated aCSF and stored at room temperature (22–24°C) until used.

Electrophysiology and data analysis.

For electrophysiological recordings, a slice was transferred to a submersion-type recording chamber, continuously perfused (∼2 ml/min) with a standard solution bubbled with a gas mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. All recordings were performed at 30–32°C. Patch pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were pulled from thin-wall (1.5-mm o.d., 1.17-mm i.d.) borosilicate glass (GC150T-7.5; Clark, Reading, UK) on a horizontal electrode puller (P-97; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). The pipette internal solution contained (in mM) 135 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 10 HEPES, 4 MgATP, 20 phosphocreatine (Na+), 0.3 NaGTP, and 0.2 EGTA, pH 7.3 (295 mosmol/l). Whole cell recordings of PVN neurons were made under visual control using infrared differential interference contrast video microscopy in combination with epifluoresence illumination, as previously described (Jackson et al. 2005; Stern 2001). Recordings were obtained with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). No correction was made for the pipette liquid junction potential (measured to be ∼10 mV). The series resistance was monitored throughout the experiment, and data were discarded if series resistance during recordings doubled from the value obtained at the beginning of the recording. The voltage output was digitized at 16-bit resolution in conjunction with pClamp 8 software (Digidata 1320; Axon Instruments). Data were digitized at 10 kHz and transferred to a disk. All neurons included in the analysis had membrane potentials of −40 mV or more negative and action potentials of at least +55 mV. Cell input resistance and cell capacitance were calculated in voltage clamp by using a 5-mV pulse while holding the cells at −70 mV. To measure single action potential properties, neurons were current-clamped close to Na+ spike threshold and a 5-ms, 0.1-nA depolarizing pulse was applied. The action potential properties were analyzed using a peak detection program (MiniAnalysis; Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ). Spike threshold was calculated based on the third derivative of the action potential waveform implemented by MiniAnalysis software (Botta et al. 2010; Meeks et al. 2005; Sonner and Stern 2007). Spike amplitude was then measured from the estimated threshold to the peak of the action potential, whereas spike width was measured at 50% of the peak. (Sonner and Stern 2007). To study the input-output relationship of PVN neurons, repetitive firing was evoked by injecting 400-ms depolarizing current pulses of varying amplitudes, and plots of the number of evoked spikes as a function of the injected current were generated. Given the high degree of action potential dampening observed in some groups during repetitive firing (see results), we used an arbitrary criterion to define “spikelets” as those waves whose amplitude was between 10 and 30% of the first spike in the train. Waves <10% were not considered for analysis. The amplitude of the hyperpolarizing afterpotential (HAP), a membrane hyperpolarization that follows the falling phase of individual action potential beyond resting membrane potential (Vm), was calculated and compared among groups. The amplitude of the afterhyperpolarizing potential (AHP), a prominent hyperpolarization that typically follows a train of action potentials in supraoptic nucleus (SON) and PVN neurons (Armstrong et al. 1994; Chen and Toney 2009; Greffrath et al. 1998; Stern 2001), was measured following a 200-ms depolarizing step of 150 pA, and data were corrected for the number of spikes in each evoked train (Andrew and Dudek 1984).

Statistics.

Numerical data are means ± SE. The reported n values represent the number of recorded neurons. In most cases, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. The two main factors were physical activity (sedentary vs. trained) and blood pressure (normotensive WKY vs. hypertensive SHR). For convenience, in most cases F and related P values from the two-way ANOVA are reported in either table or figure legends, whereas post hoc P values are reported in the text. Differences in the incidence of functional properties across experimental groups were analyzed using chi-square tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Efficacy of the exercise training protocol in normotensive and hypertensive rats.

At the beginning of protocols (week 0), peak velocity attained during graded exercise test was higher in SHR than in WKY groups (1.58 ± 0.25 vs. 1.04 ± 0.29 km/h, P < 0.05, Fig. 1A). Low-intensity training was equally effective to improve treadmill performance in both groups: marked and parallel increases on the attained velocity were already observed at the third week, with further increases on the sixth week of training. At the end of protocols, T groups exhibited similar increases on treadmill performance (SHR, +1.63 ± 0.18 vs. WKY, +1.65 ± 0.23 km/h from week 0 to week 6, P < 0.05 vs. respective S controls, Fig. 1B), whereas S groups showed no significant changes during the 6-wk period. All groups gained weight during T and S protocols, but body weight gain was smaller in T groups compared with S controls (on average, +143 ± 4 and +166 ± 4 g for T and S groups, respectively, corresponding to a 14% decrease, Fig. 1C). At the end of protocols, tail pressure was significantly increased in SHR-S vs. WKY-S and significantly decreased by training only in the SHR group (−8.3%, Fig. 1D). We have previously shown that SHR rats of similar age and strain were already in the established phase of hypertension when the training protocol started (Amaral et al. 2000; Martins at al. 2005).

Exercise training differentially affects repetitive firing of PVN-NTS neurons in normotensive and hypertensive rats.

Electrophysiological recordings were obtained from retrogradely labeled, PVN-NTS projecting neurons (PVN-NTS) in four experimental groups: WKY S (n = 24), WKY-T (n = 29), SHR-S (n = 28), and SHR-T (n = 16). As previously described (Stern 2001), recorded PVN-NTS neurons were characterized by the presence of a low-threshold spike when depolarized from a hyperpolarized membrane potential (not shown). The majority of PVN-NTS neurons recorded in our conditions were spontaneously active (WKY-S: 20/24, 0.56 ± 0.14 Hz; WKY-T: 23/29, 0.62 ± 0.18 Hz; SHR-S: 19/28, 0.68 ± 0.24 Hz; and SHR-T: 10/16, 0.59 ± 0.26 Hz), and no differences in the incidence of spontaneous activity (P > 0.3, chi-square test) or firing rate (P > 0.9) were observed among groups.

Repetitive firing in PVN-NTS neurons was evoked by injecting depolarizing current pulses of incremental amplitude (10–200 pA). Representative examples of repetitive firing evoked in the four experimental groups are shown in Fig. 2.

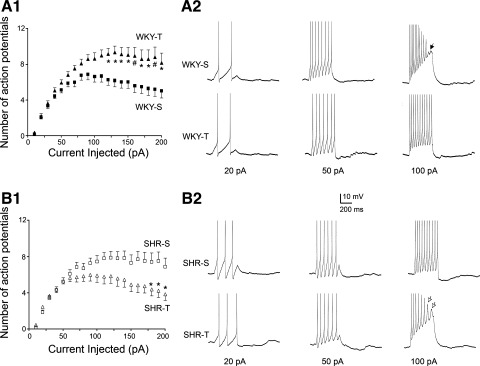

Fig. 2.

Exercise training differentially affects the input-output (I/O) function of paraventricular neurons that innervate the nucleus tractus solitarii (PVN-NTS) in WKY and SHR rats. A1: plot of the mean number of spikes (including action potential and “spikelets”) as a function of current injection obtained in WKY-S and WKY-T rats. Neurons in WKY-T rats responded to current stimulation by generating a higher number of action potentials than in WKY-S rats. A2: representative traces of repetitive firing evoked in PVN-NTS neurons from WKY-S and WKY-T rats in response to increasing depolarizing steps. B1: plot of the mean number of spikes as a function of current injection obtained in SHR-S and SHR-T rats. Neurons in SHR-T rats responded to current stimulation by generating a lower number of action potentials than in SHR-S rats. Note that repetitive firing in SHR-S neurons was basally as high as that in WKY-T and that exercise training normalized the I/O function back to control levels. B2: representative traces of repetitive firing evoked in PVN-NTS neurons from SHR-S and SHR-T rats in response to increasing depolarizing steps. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 vs. respective current step in the S group. Filled arrow in A2 points to failed action potentials, whereas open arrows in B2 point to representative spikelets.

To characterize the input-output (I/O) function of recorded neurons, a plot of the mean number of evoked action potentials (including spikelets) as a function of current injected was generated for each experimental group. As we previously reported in control rats (Jackson et al. 2005), the I/O function plot in WKY-S rats displayed a roughly parabolic relationship. The firing discharge increased progressively at low-intensity stimulation, reaching a peak at 79.1 ± 2.8 pA (∼40% of maximum stimulation). Firing rate decreased thereafter, coinciding with a large degree of adaptation and/or dampening of action potential amplitude. As an index of dampening, we measured the number and proportion of spikelets recorded at a current step of 150 pA. In WKY-S rats, we measured 1.6 ± 0.3 spikelets, which represented 24.2 ± 3.5% of the total number of spikes detected (see Fig. 3). Exercise training in WKY rats significantly enhanced the I/O function, resulting in an overall increase in the number of action potentials evoked in response to depolarizing stimulation (F = 97.2, P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA). Thus, in PVN-NTS neurons from WKY-T rats, the firing discharge increased progressively with stimulation amplitude, reaching on average a maximum firing frequency at 127.1 ± 11.9 pA (∼65% of the maximum stimulation), a value significantly higher than that observed in neurons from WKY-S rats (P < 0.0001). In this experimental group, the total number of spikelets was similar to that in WKY-S rats (1.7 ± 0.6, P > 0.9), although their proportion was significantly diminished (14.0 ± 4.4%, P < 0.05) due to the total higher number of spikes in this group (see Fig. 3). This indicates that the training-induced increase in firing discharge was not mainly due to an increase in the number of spikelets.

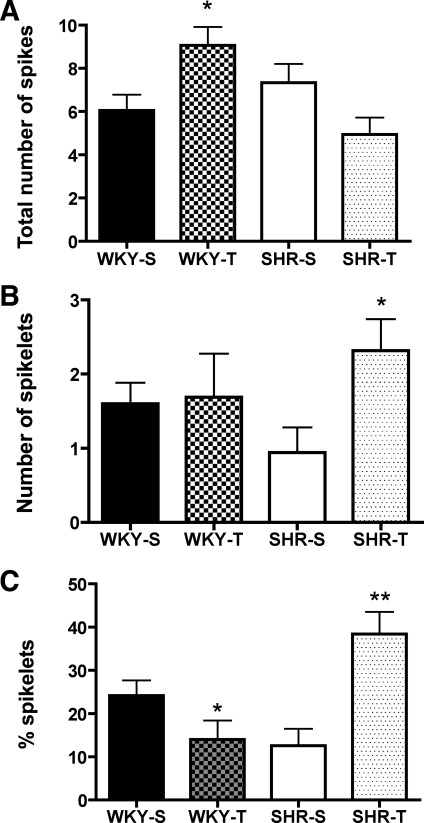

Fig. 3.

Changes in the number and proportion of spikelets in WKY and SHR rats from S and T groups. A–C: the mean total number of action potentials (A), mean number of spikelets (B), and mean proportion of spikelets (C) following a depolarizing pulse of 150 pA for WKY-S, WKY-T, SHR-S, and SHR-T rats. Note that the data shown in A correspond to the same points displayed in Fig. 2, A1 and B1, for 150 pA. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. respective S control.

Interestingly, opposite results were observed in SHR rats. In SHR-S rats, the I/O function was similar to that observed in WKY-T rats. Thus, in this group, the firing discharge increased progressively, showing little adaptation and/or dampening of action potential firing, reaching maximal firing frequency at 127.3 ± 10.2 pA (∼65% of the maximum stimulation). At a current step of 150 pA, we measured 0.9 ± 0.3 spikelets, which represented 12.6 ± 3.9% of the total number of spikes detected. In contrast to WKY rats, exercise training in SHR rats significantly diminished the gain of the I/O function, resulting in an overall lower number of action potentials in response to depolarizing stimulation (F = 46.7, P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA). Thus, in PVN-NTS neurons from SHR-T rats, the firing discharge increased progressively at low stimulation, decreasing thereafter, as observed in WKY-S rats. The maximum firing discharge in SHR-T rats was attained on average at 85.6 ± 11.8 pA, a value significantly smaller than that observed in SHR-S rats (P < 0.02). In SHR-T rats, the total number of spikelets (2.3 ± 0.4), as well as their relative proportion (38.4 ± 5.2%), increased significantly compared with WKY-S rats (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively). This indicates that the training-induced decrease in firing discharge in SHR rats was partially due to an increase in the number of spikelets.

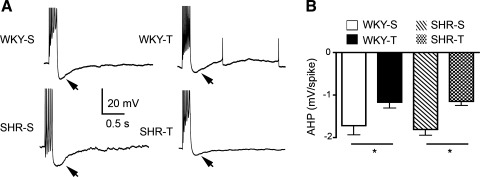

Trains of action potentials in PVN-NTS neurons were followed by a prominent AHP (see examples in Fig. 4). Exercise training was found to diminish the magnitude of the AHP in both WKY and SHR rats (P < 0.05 in both cases). Similar results were observed when the AHP area was analyzed (not shown).

Fig. 4.

Exercise training diminishes the magnitude of the afterhyperpolarizing potential (AHP) in both WKY and SHR rats. A: representative traces showing the effects of exercise training on evoked AHPs (arrows) in WKY (top) and SHR rats (bottom). Each trace represents an average of 8 sweeps. Action potentials were cropped. B: on average, the AHP magnitude in PVN-NTS neurons from both WKY and SHR rats was significantly diminished by training compared with sedentary rats [2-way ANOVA results: blood pressure F = 0.04; exercise F = 13.5 (P < 0.0005), interaction F = 0.1]. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

Exercise training differentially affects action potential properties of PVN-NTS neurons in normotensive and hypertensive rats.

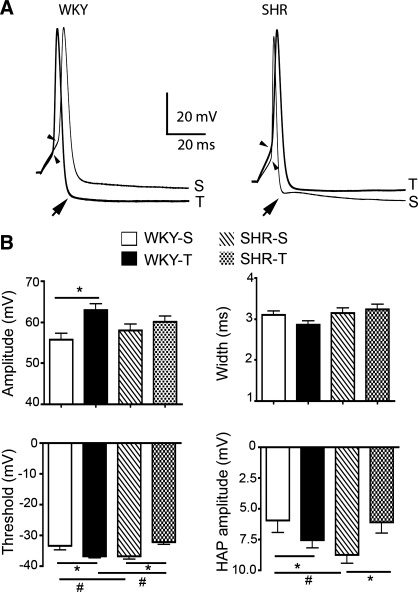

To determine whether the properties of Na+ action potentials varied among groups, individual action potentials were evoked using brief depolarizing pulses while Vm was maintained at approximately −50 mV. Representative examples and mean values are summarized in Fig. 5. Interestingly, exercise training affected spike threshold in opposing manners in WKY and SHR rats. Thus, although exercise significantly shifted spike threshold to a more hyperpolarized Vm in WKY rats (P < 0.05), a depolarizing shift was observed in SHR rats (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Exercise training affected the Na+ action potential waveform of PVN-NTS neurons in WKY and SHR rats. A: representative traces showing the effects of exercise training on Na+ action potentials evoked in PVN-NTS neurons from WKY (left) and SHR rats (right). The thin and thick traces correspond to rats from S and T protocols, respectively. Action potentials were aligned to better compare their waveform. Arrows point to hyperpolarizing afterpotentials (HAP) that followed each evoked action potential; arrowheads point to spike threshold. Traces represent an average of 15 sweeps. B: bar graphs depicting mean values for action potential amplitude (top left), width (top right), threshold (bottom left), and HAP amplitude (bottom right) in PVN-NTS neurons from WKY and SHR rats. Two-way ANOVA results are as follows: amplitude: blood pressure F = 0.01, exercise F = 5.9 (P < 0.02), interaction F = 1.7; width: blood pressure F = 3.5, exercise F = 0.7, interaction F = 2.6; threshold: blood pressure F = 0.3, exercise F = 0.3, interaction F = 13.3 (P < 0.001); and HAP amplitude: blood pressure F = 0.5, exercise F = 0.4, interaction F = 6.5 (P < 0.01).*P < 0.05; #P < 0.05.

As previously reported (Jackson et al. 2005), we found exercise training to increase the amplitude of action potentials in WKY rats (P < 0.05). However, no significant differences were observed in SHR rats (P > 0.5, Fig. 5). Exercise training did not affect the action potential width in either WKY or SHR rats (P > 0.5, Fig. 5).

Na+ spikes in PVN-NTS neurons were followed by a large HAP. Whereas exercise training significantly enhanced the peak amplitude of the HAP in WKY rats (P < 0.05), the opposite effect was observed in SHR rats (P < 0.05 in both cases, Fig. 5).

Basic intrinsic membrane properties of PVN-NTS neurons.

Table 1 summarizes mean values for some of the basic membrane properties obtained from PVN-NTS neurons in the four experimental groups. Vm and input resistance were similar among all groups. Cell capacitance, on the other hand, was significantly lower in PVN-NTS neurons from SHR compared with WKY in both sedentary and trained rats (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively; Bonferroni test).

Table 1.

Comparison of the effect of exercise training on basic membrane properties of sedentary and exercise-trained WKY and SHR rats

| Resting Vm, mV | Input Resistance, MΩ | Cell Capacitance, pC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WKY-S | −42.7 ± 1.4 | 1.11 ± 0.09 | 36.7 ± 2.7 |

| WKY-T | −42.2 ± 1.3 | 1.09 ± 0.12 | 46.1 ± 4.5 |

| SHR-S | −45.5 ± 1.0 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 25.6 ± 2.2* |

| SRH-T | −42.5 ± 1.5 | 0.89 ± 0.11 | 29.4 ± 2.4† |

Values are means ± SE in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) on sedentary (S) and exercise training (T) protocols.

P < 0.01 vs. WKY-S.

P < 0.001 vs. WKY-T. Two-way ANOVA results: resting membrane potential (Vm): blood pressure F = 1.6, exercise F = 2.0, interaction F = 0.5; input resistance: blood pressure F = 1.6, exercise F = 0.7, interaction F = 0.4; and cell capacitance: blood pressure F = 16.9 (P < 0.0001), exercise F = 5.5 (P < 0.05), interaction F = 1.8.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we investigated the effects of exercise training on the intrinsic membrane excitability of PVN-NTS neurons in normotensive WKY and hypertensive SHR rats. A major finding of this work is that exercise training differentially affected neuronal excitability and repetitive firing properties of neurons from WKY and SHR rats. As we previously reported in normal Wistar rats (Jackson et al. 2005), exercise training enhanced the I/O function of PVN-NTS neurons in WKY rats. Importantly, SHR rats under sedentary conditions already displayed an increased excitability and enhanced I/O function, as indicated by an increased number of action potentials fired in response to depolarizing stimuli, compared with WKY-S rats. In this group, as opposed to what we observed in WKY rats, exercise training diminished the I/O function, restoring repetitive firing properties back to the levels observed in sedentary WKY rats.

In all tested groups, the firing discharge of PVN-NTS neurons increased progressively at low stimulation levels. However, neurons from WKY-S rats were only able to sustain continuous firing discharge up to ∼40% of the maximal stimulation used. At higher stimulation, their firing discharge decreased progressively, and a high degree of adaptation and dampening of action potential amplitude became evident. This suggests that PVN-NTS neurons under normal conditions possess intrinsic mechanisms that prevent their excessive activation in response to incoming depolarizing stimuli. This adaptive response however, was blunted following exercise training, as shown by an enhanced firing responsiveness at high stimulation levels, with little or no action potential dampening. On the other hand, PVN-NTS neurons in SHR-S rats displayed an I/O function that was similar to that observed in WKY-T rats, displaying little or no adaptation to depolarizing stimuli, being thus able to sustain continuous repetitive firing throughout the stimuli applied. Interestingly, exercise training in this group restored adaptive mechanisms, resulting in a similar I/O profile as that observed in WKY-S rats, i.e., diminished firing discharge and dampening of action potentials during sustained firing.

Action potential dampening was reflected as a progressive decrease in the magnitude of action potentials, leading occasionally to action potential failure. Although we did observe exercise-mediated changes in the number of spikelets, particularly in the SHR rats, they did not account for the overall changes in firing properties reported among groups (i.e., full action potentials were also affected). The functional significance and precise mechanisms underlying the generation of these smaller amplitude action potentials, also known as spikelets, is at present unknown. It was previously shown that the spikelets not only can result from the progressive inactivation due to depolarization inactivation but also that they can reflect electrical coupling between neurons, ectopic axonal spikes, or spikes originating at dendritic sites (Avoli et al. 1998; Galarreta and Hestrin 1999; MacVicar and Dudek 1981). Moreover, whether spikelets are capable or not of propagating down the axon is controversial, with some studies supporting propagation (Foust et al. 2010; Shu et al. 2007) while other do not (Khaliq and Raman 2005; Monsivais et al. 2005).

Taken together, our data suggest that exercise training differentially affects neuronal excitability of PVN-NTS neurons under physiological and pathological conditions. Thus, as further discussed below, one reasonable interpretation of these results is that exercise training in normal conditions increases neuronal excitability as an adaptive mechanism to cope with the increased cardiovascular demands related to exercise, whereas in pathological conditions, such as hypertension, exercise acts as a “corrective” factor, which normalizes the abnormally elevated neuronal excitability and repetitive firing properties observed in this condition.

Potential mechanisms underlying the differential effects of exercise training in PVN-NTS neuronal excitability in normotensive and hypertensive rats.

The repetitive firing properties and the I/O function of a neuron could be influenced by a variety of intrinsic mechanisms, including changes in input resistance, action potential waveform, and postspike properties such as HAPs and AHPs.

In this study, we observed common differences among groups that shared similar repetitive firing properties. These could be mostly related to the degree of voltage-gated Na+ channel inactivation, which in turn influences the degree of action potential dampening/failure during repetitive firing (Jackson et al. 2005). For example, neurons showing low ability to sustain continuous repetitive firing due to a high degree of action potential dampening (WKY-S and SHR-T) displayed smaller HAPs than those showing enhanced ability to sustain repetitive firing (WKY-T and SHR-S). The membrane repolarization mediated by the HAP is an important mechanism that removes Na+ inactivation following an action potential, and differences in HAP magnitude would result in a differential degree of removal of Na+ channel inactivation during repetitive firing (i.e., larger HAPs lead to more efficiently removal Na+ channel inactivation, better supporting, in turn, repetitive firing discharge). Comparable differences among groups sharing similar repetitive firing profiles were observed with respect to the Na+ action potential threshold, which is also largely dependent on the degree of Na+ channel availability. Thus neurons showing low ability to sustain repetitive firing (WKY-S and SHR-T), displayed more depolarized spike thresholds than those showing enhanced ability to sustain repetitive firing (WKY-T and SHR-S). As a caveat however, despite differences in spike threshold; no major differences in firing properties among groups were observed with the lowest intensity current injections. Thus it is tempting to speculate that differences in Na+ channel availability and/or channel properties (e.g., shift in the voltage-dependent properties of inactivation, changes in Na+ channel densities) may contribute to the differential ability of PVN-NTS neurons to sustain firing in response to strong depolarizing inputs in the different experimental conditions. However, other potential mechanisms should be considered, including altered resting K+ conductances as well as altered spinning-evoked changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels. Elucidating the precise underlying mechanisms contributing to the altered repetitive firing properties reported in this study must be the focus of future studies.

The slow AHP that typically follows a train of action potentials in SON and PVN neurons (Armstrong et al. 1994; Chen and Toney 2009; Greffrath et al. 1998; Stern 2001) is another important membrane property known to influence repetitive firing. The AHP results from progressive accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ and subsequent activation of Ca2+-dependent SK potassium channels (Greffrath et al. 1998), resulting in spike frequency adaptation during repetitive firing. In a recent study, a reduced AHP was found to contribute to increased excitability of presympathetic RVLM-projecting PVN neurons in angiotensin II–high-salt-diet hypertensive rats (Chen et al. 2010). In our study, however, we found no differences in the AHP magnitude in PVN-NTS neurons between WKY and SHR rats, indicating that changes in AHP during hypertension are either cell type dependent or depend on the experimental model of hypertension used. Moreover, we found exercise training to diminish the AHP magnitude in both WKY and SHR rats. Given that exercise training affected repetitive firing in an opposing manner in these two experimental groups, it is unlikely that differences or changes in AHP magnitude constitute an underlying mechanism mediating changes in repetitive firing discharge. Finally, the lack of significant differences in input resistance among groups also argues against this as an important factor contributing to differences in repetitive firing. Interestingly, as we previously reported in PVN-RVLM neurons (Sonner et al. 2008), we found the cell capacitance in PVN-NTS neurons to be diminished in hypertensive compared with normotensive rats. Given that cell capacitance is a general indicator of neuronal surface membrane (Lindau and Neher 1988), these results may reflect somatodendritic structural changes in of PVN-NTS neurons during hypertension. Although we previously showed this to be the case in PVN-RVLM neurons (Sonner et al. 2008), additional morphometric studies in intracellularly labeled PVN-NTS neurons would be needed to confirm hypertension-related structural plasticity in this PVN neuronal population.

Another caveat in our study is that the neurochemical identity of the recorded PVN-NTS neurons was not determined. Moreover, although our tracer injection was centered within caudal aspects of the NTS, the tracer also expanded into more rostral and ventral regions, thus involving multiple NTS subnuclei. Therefore, it is likely that a heterogeneous population of PVN-NTS projecting neurons was sampled in this study. We recently showed that the majority (∼65%) of the PVN-NTS neuronal population under basal conditions express either oxytocin (OT) or vasopressin (VP) peptides (Jackson et al. 2005). However, other neurotransmitters were also implicated in this pathway, including enkephalin, somatostatin, galanin, and glutamate (Chen and DiCarlo 1996; Kawabe et al. 2008; Sawchenko and Swanson 1982). Thus it remains to be determined to what extent the reported changes in neuronal excitability induced by hypertension and exercise training affect discrete subpopulations of PVN-NTS neurons or, alternatively, whether PVN-NTS neurons are nonselectively affected.

Functional implications of exercise-mediated changes in PVN-NTS neuronal excitability in WKY and SHR.

Although the functional implications of the contrasting effects of exercise training in WKY and SHR rats are not straightforward, some insights may be obtained from previous work in the literature. Several reports support an enhanced PVN activation in different animal models of hypertension (Allen 2002; Li and Pan 2007a; Martin and Haywood 1998; Oliveira-Sales et al. 2009), contributing to sympathoexcitation and impaired baroreflex function, two characteristic findings in this disease state (Esler and Kaye 1998; Grassi 2004). Along these lines, PVN stimulation has been shown to diminish baroreflex responses (Chen et al. 1996; Hwang et al. 1998; Jin and Rockhold 1989; Pan et al. 2007; Patel and Schmid 1988) and to inhibit NTS barosensitive neurons (Duan et al. 1999; Kannan and Yamashita 1983), actions that could be mediated, at least in part, by neuropeptide-mediated modulation of presynaptic glutamate release from solitary tract primary afferent inputs (Bailey et al. 2006). Whereas all the above studies were conducted in male rats, a suppression of baroreflex function following inhibition of the PVN was recently reported in females (Page et al. 2011), suggesting that PVN influence on baroreflex function could be gender specific. In addition, VP and OT, two of the major peptides involve in descending PVN pathways (Sawchenko and Swanson 1982) and densely present in the NTS (Maley 1996; Sofroniew and Schrell 1981), have been shown to evoke pressor responses acting within the NTS (Matsuguchi and Schmid 1982; Matsuguchi et al. 1982; Pittman and Franklin 1985). Taken together, these data suggest that increased activity of descending peptidergic PVN-NTS pathways may contribute to altered autonomic function in hypertensive conditions. Results from the present study showing an enhanced excitability and firing responsiveness of PVN-NTS neurons in SHR rats further support this notion.

Accumulating evidence also supports enhanced activation of PVN-NTS projections during exercise training in normal rats. (Braga et al. 2000; Dufloth et al. 1997; Jackson et al. 2005). On the basis of the evidence above, a blunted baroreflex function would be expected in exercise-trained rats. Indeed, several reports have shown blunted baroreflex function during exercise training, particularly reduced baroreflex-mediated sympathoexcitation (Alvarez et al. 2005; Bedford and Tipton 1987; Chen and DiCarlo 1996; DiCarlo and Bishop 1988; Negrao et al. 1993). However, it is important to acknowledge that opposite effects have been also reported (Ceroni et al. 2009; DiCarlo and Bishop 1990; Fadel et al. 2001). Thus this topic remains controversial.

In the present study we found exercise to diminish PVN-NTS neuronal excitability, correcting the repetitive firing profile back to that observed in normotensive rats (Higa-Taniguchi et al. 2007). The “corrective” effect of exercise training on the repetitive firing profile of PVN-NTS neurons in SHR rats is in line with previous results from our laboratories showing that exercise training improved the blunted baroreflex function found in SHR rats (Ceroni et al. 2009). Similarly, exercise training was recently shown to normalize elevated PVN levels of AT1a receptors, NADPH oxidase subunit, and superoxide in angiotensin II-treated rats, correcting as well the blunted baroreflex function observed in this condition (Pan et al. 2007). Finally, it is important to consider that the selective decrease in blood pressure evoked by exercise training in SHR rats likely involves mechanisms other than those targeting central autonomic regulation, including arteriole structural remodeling. This is supported by our previous studies showing that exercise training normalized the wall-to-lumen ratio of skeletal muscle, heart, and diaphragm arterioles in SHR but not in WKY rats (Amaral and Michelini 2011; Amaral et al. 2000; Melo et al. 2003).

In summary, our studies add to the growing notion that overactivation of descending preautonomic PVN pathways in hypertensive disorders involves not only changes in extrinsic factors, including altered efficacy (Li and Pan 2006) and redistribution of synaptic inputs (Biancardi et al. 2010), but also changes in intrinsic neuronal properties (see also Chen et al. 2010; Sonner et al. 2008, 2011). Moreover, our results indicate that exercise constitutes an efficient approach to correct abnormal hypothalamic neuronal function in hypertensive conditions, which in turn may contribute to the beneficial cardiovascular effects of exercise in hypertensive individuals.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01 HL085767 (to J. E. Stern), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo Research Grants 02/11937-9 and 06/50548-9. Michelini is a Research Fellow of CNPq.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.E.S. and L.C.M. conception and design of research; J.E.S. and L.C.M. interpreted results of experiments; J.E.S. and L.C.M. drafted manuscript; J.E.S. edited and revised manuscript; J.E.S. approved final version of manuscript; P.M.S., S.J.S., F.C.S., and K.J. performed experiments; P.M.S., S.J.S., and F.C.S. analyzed data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of P. M. Sonner: Department of Neuroscience, Cell Biology and Physiology, Wright State University, Dayton, OH 45435.

REFERENCES

- Aghajanian and Rasmussen, 1989. Aghajanian GK, Rasmussen K. Intracellular studies in the facial nucleus illustrating a simple new method for obtaining viable motoneurons in adult rat brain slices. Synapse 3: 331–338, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, 2002. Allen AM. Inhibition of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in spontaneously hypertensive rats dramatically reduces sympathetic vasomotor tone. Hypertension 39: 275–280, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez et al., 2005. Alvarez GE, Halliwill JR, Ballard TP, Beske SD, Davy KP. Sympathetic neural regulation in endurance-trained humans: fitness vs. fatness. J Appl Physiol 98: 498–502, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral and Michelini, 2011. Amaral SL, Michelini LC. Effect of gender on training-induced vascular remodeling in SHR. Braz J Med Biol Res 44: 814–826, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral et al., 2000. Amaral SL, Zorn TM, Michelini LC. Exercise training normalizes wall-to-lumen ratio of the gracilis muscle arterioles and reduces pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 18: 1563–1572, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew and Dudek, 1984. Andrew RD, Dudek FE. Intrinsic inhibition in magnocellular neuroendocrine cells of rat hypothalamus. J Physiol 353: 171–185, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong et al., 1994. Armstrong WE, Smith BN, Tian M. Electrophysiological characteristics of immunochemically identified rat oxytocin and vasopressin neurones in vitro. J Physiol 475: 115–128, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong et al., 1980. Armstrong WE, Warach S, Hatton GI, McNeill TH. Subnuclei in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: a cytoarchitectural, horseradish peroxidase and immunocytochemical analysis. Neuroscience 5: 1931–1958, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli et al., 1998. Avoli M, Methot M, Kawasaki H. GABA-dependent generation of ectopic action potentials in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 10: 2714–2722, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey et al., 2006. Bailey TW, Jin YH, Doyle MW, Smith SM, Andresen MC. Vasopressin inhibits glutamate release via two distinct modes in the brainstem. J Neurosci 26: 6131–6142, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford and Tipton, 1987. Bedford TG, Tipton CM. Exercise training and the arterial baroreflex. J Appl Physiol 63: 1926–1932, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi et al., 1995. Bergamaschi C, Campos RR, Schor N, Lopes OU. Role of the rostral ventrolateral medulla in maintenance of blood pressure in rats with Goldblatt hypertension. Hypertension 26: 1117–1120, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancardi et al., 2010. Biancardi VC, Campos RR, Stern JE. Altered balance of gamma-aminobutyric acidergic and glutamatergic afferent inputs in rostral ventrolateral medulla-projecting neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus of renovascular hypertensive rats. J Comp Neurol 518: 567–585, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta et al., 2010. Botta P, de Souza FM, Sangrey T, De Schutter E, Valenzuela CF. Alcohol excites cerebellar Golgi cells by inhibiting the Na+/K+ ATPase. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 1984–1996, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga et al., 2000. Braga DC, Mori E, Higa KT, Morris M, Michelini LC. Central oxytocin modulates exercise-induced tachycardia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R1474–R1482, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brum et al., 2000. Brum PC, Da Silva GJ, Moreira ED, Ida F, Negrao CE, Krieger EM. Exercise training increases baroreceptor gain sensitivity in normal and hypertensive rats. Hypertension 36: 1018–1022, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceroni et al., 2009. Ceroni A, Chaar LJ, Bombein RL, Michelini LC. Chronic absence of baroreceptor inputs prevents training-induced cardiovascular adjustments in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp Physiol 94: 630–640, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen and DiCarlo, 1996. Chen CY, DiCarlo SE. Daily exercise and gender influence arterial baroreflex regulation of heart rate and nerve activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1840–H1848, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al., 2010. Chen QH, Andrade MA, Calderon AS, Toney GM. Hypertension induced by angiotensin II and a high salt diet involves reduced SK current and increased excitability of RVLM projecting PVN neurons. J Neurophysiol 104: 2329–2337, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen and Toney, 2009. Chen QH, Toney GM. Excitability of paraventricular nucleus neurones that project to the rostral ventrolateral medulla is regulated by small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J Physiol 587: 4235–4247, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al., 1996. Chen YL, Chan SH, Chan JY. Participation of galanin in baroreflex inhibition of heart rate by hypothalamic PVN in rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1823–H1828, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, 1977. Clausen JP. Effect of physical training on cardiovascular adjustments to exercise in man. Physiol Rev 57: 779–815, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins et al., 2000. Collins HL, Rodenbaugh DW, DiCarlo SE. Daily exercise attenuated the sympathetic component of the spontaneous arterial baroreflex control of heart rate in hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens 22: 607–622, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coote et al., 1998. Coote JH, Yang Z, Pyner S, Deering J. Control of sympathetic outflows by the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 25: 461–463, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney et al., 2005. Dampney RA, Horiuchi J, Killinger S, Sheriff MJ, Tan PS, McDowall LM. Long-term regulation of arterial blood pressure by hypothalamic nuclei: some critical questions. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 32: 419–425, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo and Bishop, 1988. DiCarlo SE, Bishop VS. Exercise training attenuates baroreflex regulation of nerve activity in rabbits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 255: H974–H979, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo and Bishop, 1990. DiCarlo SE, Bishop VS. Exercise training enhances cardiac afferent inhibition of baroreflex function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 258: H212–H220, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan et al., 1999. Duan YF, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Stimulation of the paraventricular nucleus modulates firing of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R403–R411, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufloth et al., 1997. Dufloth DL, Morris M, Michelini LC. Modulation of exercise tachycardia by vasopressin in the nucleus tractus solitarii. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1271–R1282, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle et al., 1992. Earle ML, Boorman R, Takahashi Y, Pittman QJ. Lesions of the paraventricular nucleus alter the development and intensity of chronic renal hypertension. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 70: Avii–Aviii, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Esler and Kaye, 1998. Esler M, Kaye D. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity and its therapeutic reduction in arterial hypertension, portal hypertension and heart failure. J Auton Nerv Syst 72: 210–219, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel et al., 2001. Fadel PJ, Stromstad M, Hansen J, Sander M, Horn K, Ogoh S, Smith ML, Secher NH, Raven PB. Arterial baroreflex control of sympathetic nerve activity during acute hypotension: effect of fitness. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2524–H2532, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust et al., 2010. Foust A, Popovic M, Zecevic D, McCormick DA. Action potentials initiate in the axon initial segment and propagate through axon collaterals reliably in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 30: 6891–6902, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta and Hestrin, 1999. Galarreta M, Hestrin S. A network of fast-spiking cells in the neocortex connected by electrical synapses. Nature 402: 72–75, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, 2004. Grassi G. Sympathetic and baroreflex function in hypertension: implications for current and new drugs. Curr Pharm Des 10: 3579–3589, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greffrath et al., 1998. Greffrath W, Martin E, Reuss S, Boehmer G. Components of after-hyperpolarization in magnocellular neurones of the rat supraoptic nucleus in vitro. J Physiol 513: 493–506, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa et al., 2002. Higa KT, Mori E, Viana FF, Morris M, Michelini LC. Baroreflex control of heart rate by oxytocin in the solitary-vagal complex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R537–R545, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa-Taniguchi et al., 2007. Higa-Taniguchi KT, Silva FC, Silva HM, Michelini LC, Stern JE. Exercise training-induced remodeling of paraventricular nucleus (nor)adrenergic innervation in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1717–R1727, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang et al., 1998. Hwang KR, Chan SH, Chan JY. Noradrenergic neurotransmission at PVN in locus ceruleus-induced baroreflex suppression in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H1284–H1292, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson et al., 2005. Jackson K, Silva HM, Zhang W, Michelini LC, Stern JE. Exercise training differentially affects intrinsic excitability of autonomic and neuroendocrine neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neurophysiol 94: 3211–3220, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin and Rockhold, 1989. Jin CB, Rockhold RW. Effects of paraventricular hypothalamic microinfusions of kainic acid on cardiovascular and renal excretory function in conscious rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 251: 969–975, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judy and Farrell, 1979. Judy WV, Farrell SK. Arterial baroreceptor reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 1: 605–614, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judy et al., 1976. Judy WV, Watanabe AM, Henry DP, Besch HR, Jr, Murphy WR, Hockel GM. Sympathetic nerve activity: role in regulation of blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Circ Res 38: 21–29, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan and Yamashita, 1983. Kannan H, Yamashita H. Electrophysiological study of paraventricular nucleus neurons projecting to the dorsomedial medulla and their response to baroreceptor stimulation in rats. Brain Res 279: 31–40, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe et al., 2008. Kawabe T, Chitravanshi VC, Kawabe K, Sapru HN. Cardiovascular function of a glutamatergic projection from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the rat. Neuroscience 153: 605–617, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaliq and Raman, 2005. Khaliq ZM, Raman IM. Axonal propagation of simple and complex spikes in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 25: 454–463, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li and Pan, 2007a. Li DP, Pan HL. Glutamatergic inputs in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus maintain sympathetic vasomotor tone in hypertension. Hypertension 49: 916–925, 2007a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li and Pan, 2006. Li DP, Pan HL. Plasticity of GABAergic control of hypothalamic presympathetic neurons in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1110–H1119, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li and Pan, 2007b. Li DP, Pan HL. Role of gamma-aminobutyric acid GABAA and GABAB receptors in paraventricular nucleus in control of sympathetic vasomotor tone in hypertension. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320: 615–626, 2007b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al., 2003. Li Y, Zhang W, Stern JE. Nitric oxide inhibits the firing activity of hypothalamic paraventricular neurons that innervate the medulla oblongata: role of GABA. Neuroscience 118: 585–601, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau and Neher, 1988. Lindau M, Neher E. Patch-clamp techniques for time-resolved capacitance measurements in single cells. Pflügers Arch 411: 137–146, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVicar and Dudek, 1981. MacVicar BA, Dudek FE. Electrotonic coupling between pyramidal cells: a direct demonstration in rat hippocampal slices. Science 213: 782–785, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maley, 1996. Maley BE. Immunohistochemical localization of neuropeptides and neurotransmitters in the nucleus solitarius. Chem Senses 21: 367–376, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin and Haywood, 1998. Martin DS, Haywood JR. Reduced GABA inhibition of sympathetic function in renal-wrapped hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R1523–R1529, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins et al., 2005. Martins AS, Crescenzi A, Stern JE, Bordin S, Michelini L. Hypertension and exercise training affect differentially oxytocin and oxytocin receptor expression in the brain. Hypertension 46: 1004–1009, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuguchi and Schmid, 1982. Matsuguchi H, Schmid PG. Pressor response to vasopressin and impaired baroreflex function in DOC-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 242: H44–H49, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuguchi et al., 1982. Matsuguchi H, Sharabi FM, Gordon FJ, Johnson AK, Schmid PG. Blood pressure and heart rate responses to microinjection of vasopressin into the nucleus tractus solitarius region of the rat. Neuropharmacology 21: 687–693, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks et al., 2005. Meeks JP, Jiang X, Mennerick S. Action potential fidelity during normal and epileptiform activity in paired soma-axon recordings from rat hippocampus. J Physiol 566: 425–441, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo et al., 2003. Melo RM, Martinho E, Jr, Michelini LC. Training-induced, pressure-lowering effect in SHR: wide effects on circulatory profile of exercised and nonexercised muscles. Hypertension 42: 851–857, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini, 1994. Michelini LC. Vasopressin in the nucleus tractus solitarius: a modulator of baroreceptor reflex control of heart rate. Braz J Med Biol Res 27: 1017–1032, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini, 2007a. Michelini LC. Differential effects of vasopressinergic and oxytocinergic pre-autonomic neurons on circulatory control: reflex mechanisms and changes during exercise. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 369–376, 2007a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini, 2007b. Michelini LC. The NTS and integration of cardiovascular control during exercise innormotensive and hypertensive individuals. Curr Hypertens Rep 9: 214–221, 2007b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini and Stern, 2009. Michelini LC, Stern JE. Exercise-induced neuronal plasticity in central autonomic networks: role in cardiovascular control. Exp Physiol 94: 947–960, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsivais et al., 2005. Monsivais P, Clark BA, Roth A, Hausser M. Determinants of action potential propagation in cerebellar Purkinje cell axons. J Neurosci 25: 464–472, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrao et al., 1993. Negrao CE, Irigoyen MC, Moreira ED, Brum PC, Freire PM, Krieger EM. Effect of exercise training on RSNA, baroreflex control, and blood pressure responsiveness. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 265: R365–R370, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Sales et al., 2009. Oliveira-Sales EB, Nishi EE, Carillo BA, Boim MA, Dolnikoff MS, Bergamaschi CT, Campos RR. Oxidative stress in the sympathetic premotor neurons contributes to sympathetic activation in renovascular hypertension. Am J Hypertens 22: 484–492, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn et al., 2007. Osborn JW, Fink GD, Sved AF, Toney GM, Raizada MK. Circulating angiotensin II and dietary salt: converging signals for neurogenic hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 9: 228–235, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page et al., 2011. Page MC, Cassaglia PA, Brooks VL. GABA in the paraventricular nucleus tonically suppresses baroreflex function: alterations during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R1452–R1458, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan et al., 2007. Pan YX, Gao L, Wang WZ, Zheng H, Liu D, Patel KP, Zucker IH, Wang W. Exercise training prevents arterial baroreflex dysfunction in rats treated with central angiotensin II. Hypertension 49: 519–527, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel and Schmid, 1988. Patel KP, Schmid PG. Role of paraventricular nucleus (PVH) in baroreflex-mediated changes in lumbar sympathetic nerve activity and heart rate. J Auton Nerv Syst 22: 211–219, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman and Franklin, 1985. Pittman QJ, Franklin LG. Vasopressin antagonist in nucleus tractus solitarius/vagal area reduces pressor and tachycardia responses to paraventricular nucleus stimulation in rats. Neurosci Lett 56: 155–160, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts, 2006. Potts JT. Inhibitory neurotransmission in the nucleus tractus solitarii: implications for baroreflex resetting during exercise. Exp Physiol 91: 59–72, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven et al., 2006. Raven PB, Fadel PJ, Ogoh S. Arterial baroreflex resetting during exercise: a current perspective. Exp Physiol 91: 37–49, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper et al., 1976. Saper CB, Loewy AD, Swanson LW, Cowan WM. Direct hypothalamo-autonomic connections. Brain Res 117: 305–312, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchenko and Swanson, 1982. Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus that project to the medulla or to the spinal cord in the rat. J Comp Neurol 205: 260–272, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu et al., 2007. Shu Y, Duque A, Yu Y, Haider B, McCormick DA. Properties of action-potential initiation in neocortical pyramidal cells: evidence from whole cell axon recordings. J Neurophysiol 97: 746–760, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniew and Schrell, 1981. Sofroniew MV, Schrell U. Evidence for a direct projection from oxytocin and vasopressin neurons in the hypothalamus paraventricular nucleus to the medulla oblongata: immunohistochemical visualization of both the horseradish peroxidase transported and the peptide produced by the same neurons. Neurosci Lett 22: 211–217, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- Sonner et al., 2008. Sonner PM, Filosa JA, Stern JE. Diminished A-type potassium current and altered firing properties in presympathetic PVN neurones in renovascular hypertensive rats. J Physiol 586: 1605–1622, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonner et al., 2011. Sonner PM, Lee S, Ryu PD, Lee SY, Stern JE. Imbalanced K+ and Ca2+ subthreshold interactions contribute to increased hypothalamic presympathetic neuronal excitability in hypertensive rats. J Physiol 589: 667–683, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonner and Stern, 2007. Sonner PM, Stern JE. Functional role of A-type potassium currents in rat presympathetic PVN neurones. J Physiol 582: 1219–1238, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, 2001. Stern JE. Electrophysiological and morphological properties of pre-autonomic neurones in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Physiol 537: 161–177, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson and Kuypers, 1980. Swanson LW, Kuypers HG. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: cytoarchitectonic subdivisions and organization of projections to the pituitary, dorsal vagal complex, and spinal cord as demonstrated by retrograde fluorescence double-labeling methods. J Comp Neurol 194: 555–570, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson and Sawchenko, 1983. Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE. Hypothalamic integration: organization of the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. Annu Rev Neurosci 6: 269–324, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa and Dampney, 1999. Tagawa T, Dampney RA. AT1 receptors mediate excitatory inputs to rostral ventrolateral medulla pressor neurons from hypothalamus. Hypertension 34: 1301–1307, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop et al., 1996. Waldrop TG, Eldridge FL, Iwamoto GA, Mitchell JH. Central neural control of respiration and circulation during exercise. In: Handbook of Physiology. Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1996, sect. 12, p. 330–380 [Google Scholar]

- Yang and Coote, 1998. Yang Z, Coote JH. Influence of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus on cardiovascular neurones in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat. J Physiol 513: 521–530, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]