Abstract

Multifocal epithelial hyperplasia (MEH), also known as Heck’s disease, manifests as a papulonodular lesion in the oral mucosa and has been associated with the human papillomavirus, a virus related to various precancerous diseases in the oral cavity. It has a predisposition for the female gender and for children. Although the majority of reported cases have been among American Indians and Eskimos, it has been described in multiple ethnic groups in various geographical locations. The objective of this review was to report on the clinical characteristics and epidemiology of MEH and its possible correlation with oral cancer. It is based on a search of articles in international journals published prior to April 2011, using the PubMed database and selecting articles related to the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of MEH. The review revealed a higher number of cases in individuals of American Indian origin and a predilection of the disease for the female gender and for patients between the 1st and 2nd decades of life. The most frequent lesion site was the lower lip. The disease has been associated with socio-economic and genetic factors, among others. No cases of malignant transformation have been reported.

Keywords: focal epithelial hyperplasia, multifocal epithelial hyperplasia, Heck’s disease, papillomavirus infections, human papillomavirus 13 and 32

1. Introduction

Multifocal epithelial hyperplasia (MEH) is an uncommon disease characterized by the proliferation on the oral mucosa of multiple papulonodular lesions, which are smooth, soft on palpation and generally asymptomatic (1–5). It has mainly been observed among isolated groups of native Indians in North, Central and South America and in other very small population groups in Europe and Africa (6–13).

Although previously described by other authors, the first case report was published by Dr Heck and his team in 1965, and it is therefore also known as Heck’s disease (14). In the same year, Witkop et al reported 11 cases with the same diagnosis among Xavante Indians in Brazil, a Ladino population in El Salvador and Quiche-Mayan Indians in Guatemala (13). Single cases were subsequently reported in Polynesia (15), Puerto Rico (16), in an adult female Caucasian (17), and in small population groups in Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, Colombia and Mexico (12,18–20). The disease has also been found in primates and in a rabbit, which presented with macroscopic and microscopic characteristics similar to those of humans with the disease (21–25).

2. Human papillomavirus and other etiological factors

The main etiological factor for this disease is the presence of the human papillomavirus (HPV), which belongs to a varied group of DNA viruses from the Papillomaviridae family. Similar to all viruses in this family, it only establishes productive infections in the stratified epithelium of skin and mucosa of humans and certain animals (26).

In 1971, Praetorious-Clausen and Willis first revealed HPV particles in MEH, using an electron microscope to study five samples from patients in Greenland (27). One year later, Hanks et al reported the same findings in a 5-year-old child from Cochabamba in Bolivia (28). This association was subsequently confirmed by other authors, including Kuffer and Perol in 1976, in the first reported case in France (29), and Kulhwein et al in 1981 (30).

Approximately 200 different types of HPV have been identified, mostly asymptomatic (26). In 1983, Pfiser et al related the disease to HPV-13 after examining a sample from a Turkish patient (31). Beaudenon et al confirmed this specific association in 10 patients of various origins and also observed a correlation with HPV-32 (32). Over the past few years, immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization studies have shown MEH to be closely related to HPV-13 and HPV-32, while certain studies have also demonstrated the presence of HPV-1, HPV-6, HPV-11 and HPV-16 in these patients (33–36).

Genetic predisposition is also frequently mentioned as an etiological factor for MEH (13,14). The familial presence of the disease was first highlighted by Gómez et al in Columbia in 1969 (19). In 1993, Premoli-De-Percoco found that members of six generations of a Venezuelan family had been diagnosed with MEH and concluded that the disease has a genetic basis, noting that all generations were born in a small village with a very strong American Indian genetic component (37). In 2004, García-Corona et al assessed the effect of genetics by studying the association of HLA-DR4 alleles (DRB1*0404) with HPV infection, yielding results in support of the genetic basis of MEH (4).

Nutritional deficiencies and environmental factors have been proposed by certain authors (15), including poverty and the lack of hygiene (38). The role of immunosuppression is also under investigation. Feller et al reported the case of a seropositive child undergoing highly active antiretroviral treatment who was also diagnosed with MEH and successfully treated by diode laser; the authors suggested that the anti-HIV therapy may have been responsible for the disease (39). In another report on an HIV-positive patient with MEH, Marvan et al concluded that the correlation between the immune state and HPV infection warranted further investigation (40).

3. Diagnosis, prognosis and treatment

The diagnosis of MEH is mainly based on the clinical features of the lesions and a biopsy pathology report. Since the discovery of HPV particles in these lesions in 1970, there has been an increase in the diagnostic use of molecular biology techniques, including in situ DNA hybridization and polymerase chain reaction, which have proven highly useful in identifying the types of HPV involved (2,5,27,28,31,41).

The prognosis of the disease is good, given that most lesions remit spontaneously, but periodical clinical follow-ups are considered crucial (42,43). Lesions that do not remit or cause functional and/or aesthetic problems may be removed by various means (44–48), including surgery, cryotherapy, electrocoagulation, laser, chemical agents (e.g., retinoic acid) or immunostimulants (e.g., interferon).

4. Criteria and variables included

Inclusion criteria

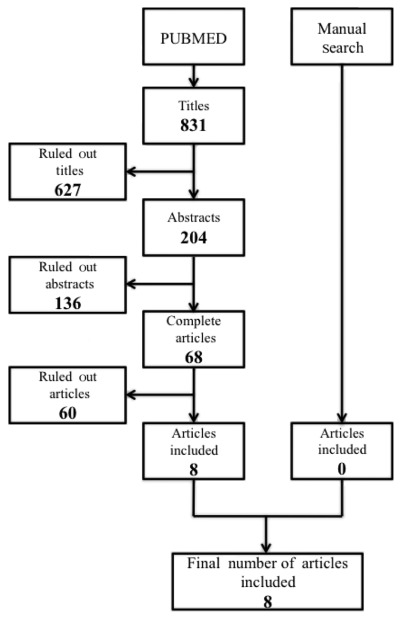

The PubMed database was used to search the international literature up to April 2011, for the following key words: Focal epithelial hyperplasia, multifocal epithelial hyperplasia, Heck’s disease, papillomavirus infections, HPV-13 and HPV-32. The search was not limited by publication year due to the scant information on the disease. Out of a total of 831 articles (in English, German and Spanish), 204 were initially selected for possible inclusion. After studying the abstracts, 68 relevant articles that could be downloaded via the Internet were selected, and a final sample of eight articles was included in the present review after applying the following inclusion criteria (Fig. 1): i) They could be any type of publication with the exception of single case reports, ii) they had to be in vivo studies, iii) the objectives had to include the description of the clinical characteristics and etiology of MEH and/or the epidemiology of the disease, iv) they could report on any clinical situation, including the presence of another disease with the exception of cancer, v) the complete text of the articles had to be available, and vi) all publication dates up to April 2011 could be included.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for selection of articles on multifocal epithelial hyperplasia.

Study variables

In an initial analysis, we gathered and analyzed the main variables related to the epidemiology of EH, including the place of origin, geographic location, gender and age.

5. Findings pertaining to multifocal epithelial hyperplasia

There have been few studies on the epidemiology and incidence of MEH, attributable in part to its low incidence. The largest number of cases has been observed in Central America, South America and Mexico. The disease is less prevalent among individuals in Asia and is even more rare among Caucasian and Black populations.

In 1965, Witkop and Niswander (13) and Archard et al (14) conducted the first epidemiological studies on American Indians, finding a predisposition for the disease in individuals in the first and second decade of life, with the lower lip being the most frequent localization. However, whereas they found no significant gender difference, observing a larger number of males with the disease, Archard et al reported a female:male ratio of 4:1 (13,14).

In a subsequent study on Eskimos in Greenland, Clausen et al found no significant gender differences. Furthermore, in contrast to previous studies, they found that the disease could also appear in adults, with an overall age range of 2 to 79 years, and that more than 50% of lesions were localized on the tongue (49). In a similar study, Henke et al found no significant gender or age differences and confirmed the possible presence of the disease in adults, reporting an age range for sufferers of 22 to 85 years (50).

In 1994, Carlos and Sedano studied a sample of 110 patients diagnosed with MEH over a three-year period in the city and rural areas of Guatemala (36). They found that 69% of the patients were female (female:male ratio, 2.2:1).

In Table I, the age range of these patients was 5 to 38 years, the mean age was 11 years, and 97.5% were in their first or second decade of life. Although five cases were excluded due to lack of information on their age, it was concluded that this condition predominantly affects children and adolescents (36).

Table I.

Distribution by decade of life.

| Age group | Number of cases | % |

|---|---|---|

| First decade | 54 | 50.5 |

| Second decade | 50 | 47.0 |

| Third decade | 2 | 2.0 |

| Fourth decade | 1 | 0.5 |

With regard to the localization of lesions (Table II), the majority were in non-keratinized mobile mucosa, excluding the soft palate, most frequently on the lower lip and buccal mucosa. Out of the 110 cases in this study, only three presented with single lesions (2.8%): two on the lower lip and one on the tongue (36).

Table II.

Distribution by localization.

| Localization | Number of cases | % |

|---|---|---|

| Upper lip | 68 | 63.55 |

| Lower lip | 103 | 96.26 |

| Right buccal mucosa | 88 | 83.06 |

| Left buccal mucosa | 92 | 85.98 |

| Tongue | 73 | 68.22 |

Tongue lesions were usually on the lateral borders, with only three cases of lesions on the ventral tongue and one on the dorsal tongue (36).

Socio-economic factors have been related to this disease. In Table III, cases are divided into five groups according to monthly family income. In nine of the 110 cases studied, the income group could not be established; 90% of the patients assessed were members of a family receiving less than $200 a month. The only patient with a high monthly income (>$910) was a 21-year-old female from a native village in Guatemala in which the presence of MEH has been reported. There were no cases among the 2,464 children in five private schools (36). These findings indicated a correlation between low socio-economic level and MEH.

Table III.

Distribution by monthly income.

| Monthly income | Number of cases | % |

|---|---|---|

| ≤$100 | 83 | 75.0 |

| $101 to 184 | 10 | 15.0 |

| $185 to 364 | 1 | 0.1 |

| $365 to 910 | 0 | 0.0 |

| >$910 | 1 | 0.1 |

In 2004, García-Corona et al studied American Indians in 2004 and found no significant differences in gender, observing that 73% of cases were in the first and second decades of life, with a mean age of 19 years (4). A later study on Indians from Colombia by Gonzáles et al (3) found a predilection for the female gender (63.3%) and a mean age of 9.8 years; the most common localization was the lower lip (66.7% of cases).

Finally, a study in Mexico by Ledesma-Montes et al (38) reported that 69.3% of patients were in their first or second decade of life and that the overall age range was 4 to 69 years; 71.1% were female. The most frequent localization was the buccal mucosa (82.6%), followed by the lips and tongue (67.3%).

None of the studies associated MEH with precancerous lesions, in spite of its close association with HPV, known to be an etiological factor in various malignant diseases.

6. Conclusions

MEH is a rare disease and its epidemiology has not been studied to a great extent. With regard to geographic localization, the majority of published cases are from the indigenous populations of the American continent and Eskimos from Greenland. The lips are the most frequent anatomical site of the disease. There is a higher prevalence in the first and second decades of life and a predilection for the female gender. Socio-economic and genetic factors, among others, have also been associated with the disease.

No correlation with malignant lesions has been reported, despite the relationship between MEH and HPV, which is an etiological agent in various precancerous lesions. However, only low-risk types of HPV have been related to the etiology of MEH, and few cases have been reported.

There is a need for further studies in various populations to permit a wider systematic review and a more updated meta-analysis of this disease.

References

- 1.Saunders NR, Scolnik D, Rebbapragada A, et al. Focal epithelial hyperplasia caused by human papillomavirus 13. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:550–552. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181cf854c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuberos V, Perez J, Lopez CJ, et al. Molecular and serological evidence of the epidemiological association of HPV 13 with focal epithelial hyperplasia: a case-control study. J Clin Virol. 2006;37:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez LV, Gaviria AM, Sanclemente G, et al. Clinical, histopathological and virological findings in patients with focal epithelial hyperplasia from Colombia. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:274–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Corona C, Vega-Memije E, Mosqueda-Taylor A, et al. Association of HLA-DR4 (DRB1*0404) with human papillomavirus infection in patients with focal epithelial hyperplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1227–1231. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.10.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Premoli-de-Percoco G, Galindo I, Ramirez JL. In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labelled DNA probes for the detection of human papillomavirus-induced focal epithelial hyperplasia among Venezuelans. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;420:295–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall C, McCullough M, Angel C, Manton D. Multifocal epithelial hyperplasia: a case report of a family of Somalian descent living in Australia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosannen-Mozaffari P, Falaki F, Amirchaghmaghi M, Pakfetrat A, Dalirsani Z, Saghafi-Khadem S. Multifocal epithelial hyperplasia, a rare oral infection in Asia: report of twelve cases in Iran. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;15:591–595. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falaki F, Amir Chaghmaghi M, Pakfetrat A, Delavarian Z, Mozaffari PM, Pazooki N. Detection of human papilloma virus DNA in seven cases of focal epithelial hyperplasia in Iran. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:773–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledesma-Montes C, Vega-Memije E, Garces-Ortiz M, Cardiel-Nieves M, Juarez-Luna C. Multifocal epithelial hyperplasia. Report of nine cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:394–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Wyk W, Harris A. Focal epithelial hyperplasia: a survey of two isolated communities in the Cape Province of South Africa. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:161–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilgard G. Focal epithelial hyperplasia. Report of nine cases from Sweden and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:540–543. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischman SL. Focal epithelial hyperplasia. Case reports from Paraguay and Peru. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1969;28:389–393. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(69)90233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witkop CJ, Jr, Niswander JD. Focal epithelial hyperplasia in central and south american Indians and Ladinos. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:213–217. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archard HO, Heck JW, Stanley HR. Focal epithelial hyperplasia: an unusual oral mucosal lesion found in Indian children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:201–212. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hettwer KJ, Rodgers MS. Focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease) in a Polynesian. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22:466–470. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips H, Williams A. Focal epithelial hyperplasia. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;26:619–622. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldman GH, Shelton DW. Focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease) in an adult Caucasian. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;26:124–127. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decker WG, De Guzman MN. Focal epithelial hyperplasia. Report of four cases in Mestizos from Cochabamba, Boliva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1969;27:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(69)90025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez A, Calle C, Arcila G, Pindborg JJ. Focal epithelial hyperplasia in a half-breed family of Colombians. J Am Dent Assoc. 1969;79:663–667. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1969.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan KN, Medak H, Cohen L, Burlakow P. Focal epithelial hyperplasia in a Mexican Indian. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollander CF, van Noord MJ. Focal epithelial hyperplasia: a virus-induced oral mucosal lesion in the chimpanzee. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;33:220–226. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tate CL, Conti PA, Nero EP. Focal epithelial hyperplasia in the oral mucosa of a chimpanzee. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1973;163:619–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Ranst M, Fuse A, Sobis H, et al. A papillomavirus related to HPV type 13 in oral focal epithelial hyperplasia in the pygmy chimpanzee. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sa LR, DiLoreto C, Leite MC, Wakamatsu A, Santos RT, Catao-Dias JL. Oral focal epithelial hyperplasia in a howler monkey (Alouatta fusca) Vet Pathol. 2000;37:492–496. doi: 10.1354/vp.37-5-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen SY. Focal epithelial hyperplasia in rabbit oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol. 1979;8:213–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1979.tb01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syrjanen S. Human papillomavirus infections and oral tumors. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2003;192:123–128. doi: 10.1007/s00430-002-0173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Praetorius-Clausen F, Willis JM. Papova virus-like particles in focal epithelial hyperplasia. Scand J Dent Res. 1971;79:362–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1971.tb02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanks CT, Fischman SL, Nino de Guzman M. Focal epithelial hyperplasia. A light and electron microscopic study of one case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;33:934–943. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuffer R, Perol Y. Focal epithelial hyperplasia. 1st French case. Demonstration of a papovavirus by electron microscopy. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1976;77:318–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhlwein A, Nasemann T, Janner M, Schaeg G, Reinel D. Detection of papilloma virus in Heck’s focal epithelial hyperplasia and the differential diagnosis of white-sponge nevus. Hautarzt. 1981;32:617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfister H, Hettich I, Runne U, Gissmann L, Chilf GN. Characterization of human papillomavirus type 13 from focal epithelial hyperplasia Heck lesions. J Virol. 1983;47:363–366. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.2.363-366.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaudenon S, Praetorius F, Kremsdorf D, et al. A new type of human papillomavirus associated with oral focal epithelial hyperplasia. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:130–135. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12525278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Syrjanen SM, Syrjanen KJ, Happonen RP, Lamberg MA. In situ DNA hybridization analysis of human papillomavirus (HPV) sequences in benign oral mucosal lesions. Arch Dermatol Res. 1987;279:543–549. doi: 10.1007/BF00413287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petzoldt D, Pfister H. HPV 1 DNA in lesions of focal epithelial hyperplasia Heck. Arch Dermatol Res. 1980;268:313–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00404293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Villiers EM, Neumann C, Le JY, Weidauer H, zur Hausen H. Infection of the oral mucosa with defined types of human papillomaviruses. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1986;174:287–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02123681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlos R, Sedano HO. Multifocal papilloma virus epithelial hyperplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:631–635. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Premoli-De-Percoco G, Cisternas JP, Ramirez JL, Galindo I. Focal epithelial hyperplasia human-papillomavirus-induced disease with a genetic predisposition in a Venezuelan family. Hum Genet. 1993;91:386–388. doi: 10.1007/BF00217363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ledesma-Montes C, Garces-Ortiz M, Hernandez-Guerrero JC. Clinicopathological and immunocytochemical study of multifocal epithelial hyperplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2211–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feller L, Khammissa RA, Wood NH, Malema V, Meyerov R, Lemmer J. Focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck disease) related to highly active antiretroviral therapy in an HIV-seropositive child. A report of a case, and a review of the literature. SADJ. 2010;65:172–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marvan E, Firth N. Focal epithelial hyperplasia in an HIV positive man. An illustrated case and review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 1998;43:305–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1998.tb00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bombeccari GP, Guzzi GP, Pallotti F, Spadari F. Focal epithelial hyperplasia: polymerase chain reaction amplification as a differential diagnosis tool. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:98–100. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31818ffc04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segura-Saint-Gerons R, Toro-Rojas M, Ceballos-Salobrena A, Aparicio-Soria JL, Fuentes-Vaamonde H. Focal epithelial hyperplasia. A rare disease in our area. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hashemipour MA, Shoryabi A, Adhami S, Mehrabizadeh Honarmand H. Extensive focal epithelial hyperplasia. Arch Iran Med Jan. 2009;13:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martins WD, de Lima AA, Vieira S. Focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease): report of a case in a girl of Brazilian Indian descent. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006;16:65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dos Santos-Pinto L, Giro EM, Pansani CA, Ferrari J, Massucato EM, Spolidorio LC. An uncommon focal epithelial hyperplasia manifestation. J Dent Child (Chic) 2009;76:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinhoff M, Metze D, Stockfleth E, Luger TA. Successful topical treatment of focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease) with interferon-beta. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1067–1069. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akyol A, Anadolu R, Anadolu Y, Ekmekci P, Gurgey E, Akay N. Multifocal papillomavirus epithelial hyperplasia: successful treatment with CO2 laser therapy combined with interferon alpha-2b. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:733–735. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luomanen M. Oral focal epithelial hyperplasia removed with CO2 laser. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19:205–207. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clausen FP, Mogeltoft M, Roed-Petersen B, Pindborg JJ. Focal epithelial hyperplasia of the oral mucosa in a south-west Greenlandic population. Scand J Dent Res. 1970;78:287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1970.tb02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henke RP, Milde-Langosch K, Loning T, Koppang HS. Human papillomavirus type 13 and focal epithelial hyperplasia of the oral mucosa: DNA hybridization on paraffin-embedded specimens. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1987;411:193–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00712744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]