Abstract

Differentiation of skeletal myoblast cells to functional myotubes involves highly regulated transcriptional dynamics. The myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) transcription factors are critical to this process, synergizing with the master regulator MyoD to promote muscle specific gene transcription. MEF2 is extensively regulated by myogenic stimuli, both transcriptionally and post-translationally, but to date there has been little progress in understanding how signals upstream of MEF2 are coordinated to produce a coherent response. In this study, we define a novel interaction between the muscle A-kinase anchoring protein (mAKAP) and MEF2 in skeletal muscle. Discrete domains of MEF2 and mAKAP bind directly. Their interaction was exploited to probe the function of mAKAP-tethered MEF2 during myogenic differentiation. Dominant interference of MEF2/mAKAP binding was sufficient to block MEF2 activation during the early stages of differentiation. Furthermore, extended expression of this disrupting domain effectively blocked myogenic differentiation, halting the formation of myotubes and decreasing expression of several differentiation markers. This study expands our understanding of the regulation of MEF2 in skeletal muscle and identifies the mAKAP scaffold as a facilitator of MEF2 transcription and myogenic differentiation.

Keywords: scaffold protein, AKAP, skeletal muscle differentiation, MEF2, myogenesis, C2C12

1. Introduction

Skeletal myogenic differentiation involves morphological and transcriptional dynamics that turn a disorganized population of mononucleated myoblasts into multinucleated striated muscle fibers known as myotubes that are capable of doing mechanical work[1]. An important myogenic transcription factor is myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2), a MADS box transcription factor with four known isoforms (MEF2A-D)[2–4]. Loss of function studies in Drosophila, where there is a single MEF2 gene, result in embryos with appropriately positioned myoblasts that cannot undergo differentiation, which suggests that MEF2 is required for muscle differentiation[5, 6]. Later studies found that MEF2 works in concert with MyoD, synergistically promoting myofiber differentiation after activation of MyoD has committed the cells to a muscle lineage[7]. Additionally, dominant negative forms of MEF2 potently inhibit myogenic differentiation[8].

The cellular regulation of the transcriptional activity of MEF2 is complex. Multiple kinases, phosphatases, sumoylases, acetylases, and deacetylases have been reported to influence MEF2 activity[9–18]. For example, in the hippocampus, sumoylation inhibits MEF2 activation while a calcineurin-dependent acetylation promotes MEF2 transcriptional activity[19]. What remains to be understood is how the myogenic signals are coordinated in order to achieve proper activation of MEF2 in a dynamic developmental environment.

Coordination of convergent signaling pathways is achieved partly through the binding of signaling molecules to scaffold proteins, thereby bringing regulatory and effector proteins in proximity to facilitate crosstalk[20]. One such scaffold is muscle A-kinase anchoring protein (mAKAP), a ~250 kDa scaffolding protein that is expressed in skeletal and cardiac myocytes, as well as neurons[21, 22]. mAKAP is localized to the nuclear envelope via an interaction with nesprin-1α, an integral nuclear membrane structural protein[23]. There, mAKAP organizes a large protein complex consisting of several signaling enzymes including protein kinase A (PKA), the phosphodiesterase PDE4D3, adenylyl cyclase V, calcineurin, protein phosphatase 2A and the big mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK5[21, 24–28]. Importantly, binding of many of these signaling enzymes to mAKAP is required for adrenergic stimulation of cardiac hypertrophy and the associated changes in gene expression[24, 26, 28].

While many studies have investigated the role of mAKAP in the regulation of cardiac gene transcription, if this regulation was common to other striated muscle was unknown. In particular, as mAKAP is known to associate with many of the effectors of MEF2 activity, it seemed plausible that the AKAP could regulate MEF2-dependent gene transcription in this muscle type. Here we show that mAKAP co-precipitates MEF2 from the well-characterized C2C12 skeletal muscle cell line. Biochemical mapping experiments show that MEF2 directly binds to amino acids 300–575 of mAKAP, a domain not previously defined to participate in any protein/protein interactions. Ectopic expression of this domain was sufficient to prevent association of MEF2 with mAKAP both in vitro and in vivo. MEF2 luciferase reporter assays show that differentiation-induced MEF2 activity is sharply reduced after disruption of the interaction. Importantly, long-term displacement of MEF2 from mAKAP significantly attenuated the formation of myotubes, suggesting that this interaction is necessary for efficient myogenic differentiation.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1 Cell Culture and Transfection

C2C12 cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-1722) and passaged at low density in Growth Medium (DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were carefully monitored to prevent spontaneous differentiation as a result of overgrowth. To induce differentiation, cells at approximately 80% confluence were washed four times with PBS to remove all growth factors and media was replaced with Differentiation Medium (DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin).

Two days prior to transfection, cells were plated at 40% confluence in Growth Medium. Cells were washed twice with PBS, trypsinized, counted, and pelleted. Approximately 2×106 cells per transfection were resuspended in supplemented Solution V from the Lonza Cell Electroporation kit (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). These were transferred to a cuvette with 2μg DNA in TE buffer, electroporated using Program T-017 of the Lonza electroporation unit, and transferred immediately to pre-warmed growth medium and allowed to rest for 8 hours. Cells were plated on 24 well plates for luciferase analysis, 60 mm dishes for biochemical experiments, and glass coverslips for microscopy.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate method for mapping experiments. Five micrograms of DNA were transfected with 20 mM CaCl2, 2X BBS, and water. These were plated 24 hours prior to transfection and analyzed one day after transfection.

2.2 Antibodies and Plasmids Utilized

MEF2 (Santa Cruz) and mAKAP (Covance) rabbit and mouse antibodies were used for immunofluorescence, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting. MyoD, actin, myogenin, and GFP antibodies (Santa Cruz) and the myosin heavy chain (clone MF-20) antibody were used for immunoblotting as noted. The MF-20 antibody developed by Donald A. Fischman, M.D. was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242.

For mapping studies, amino acids 301-510 of mAKAP and full length MEF2D were expressed using pGEX-4T2 vector (Amersham). These were expressed in the T7 strain of E. coli (NEB) and induced with IPTG (1 mM) when the culture reached an optical density of 0.5. The induced culture was allowed to grow an additional 12–18 hours before protein harvesting. Cells were lysed in GST lysis buffer (5% glycerol, 1% NP40, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA) and, following centrifugation, the soluble lysate was incubated with glutathione-agarose beads overnight at 4° C with rotation. Beads were washed three times with GST lysis buffer and aliquots subjected to electrophoresis and coomassie staining to verify protein expression and pull-down.

For purification of His-tagged recombinant mAKAP amino acids 1-585, pet30c-mAKAP 1-585 was transformed expressed in the T7 strain of E. coli (NEB) and induced with IPTG (1 mM) when the culture reached an optical density of 0.5. The induced culture was allowed to grow an additional 12–18 hours before protein harvesting. Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 5 M imidazole, and protease inhibitors. The lysate was rocked at 4° C for two hours, followed by centrifugation. The pellet was resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 5 M imidazole, 6 M urea, and protease inhibitors. After an overnight incubation at 4° C, purification of the protein was achieved by incubating the supernatant with nickel resin, and elution of the bound protein was achieved using 300 mM imidazole.

2.3 Luciferase Vectors and Assay

One day after splitting cells 1:6 as described above, adenoviral stocks were added to the culture medium. MEF2-Luciferase (Seven Hills Bioreagents), which contains three copies of the MEF2 consensus E-box sequence upstream of the firefly luciferase gene and control β-galactosidase adenoviruses were added at an MOI of 225 and 0.2, respectively. These cells were then returned to the incubator until transfection the following day as described above. Eight to ten hours post-transfection, cells were examined by phase contrast microscopy to ensure adherence, and transfection efficiency was determined by visualizing GFP or RFP fluorescence, where applicable. Cells were then washed once with PBS and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature with 80 μL 1X Reporter Lysis Buffer from the Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Twenty and 50 microliters cell lysate were use for luciferase and β-galactosidase measurement, respectively, and the remaining lysate was saved for Western blot analysis. Samples were assayed according to the manufacturer’s instructions in an injecting luminometer (Biotek Synergy 2). Normalized luciferase values were obtained by dividing luciferase by β-galactosidase. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test p values are as reported.

2.4 Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cells from 10 cm dishes were washed twice with PBS and then lysed with 1 ml HSE buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors (AEBSF, benzamidine, leupeptin/pepstatin). Following centrifugation at 13.2K rpm at 4° C, soluble cell lysates were precleared with 40 μL Protein-G agarose beads (Millipore) for 1 hour at 4° C with rotation. These beads were removed by centrifugation and the cleared lysate was incubated with 15 μL Protein-G beads and 2 μg MEF2 or mAKAP antibody overnight at 4° C. Beads were pelleted and washed three times with HSE buffer and boiled in 25 μL of 2X SDS loading buffer.

Samples were separated on either 7.5% or 10% agarose gels with SDS and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots blocked in 5% milk for one hour, followed by incubation in primary antibody overnight at 4° C. Following washes, secondary antibodies (rabbit or mouse IgG conjugated to HRP, Santa Cruz) were incubated with the membranes (1:5000) for one hour and signals were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce) and exposed to either X-ray film or a ImageQuant LAS 4000 (General Electric) imager.

2.5 Immunofluorescence

C2C12 cells, after transfection as described above, were plated on glass coverslips. These were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes at room temperature. Following three washes in PBS, coverslips were inverted onto parafilm spotted with 100 μL of 3% normal goat serum for one hour at room temperature. Coverslips were washed thrice in PBS and inverted onto parafilm spotted with 100 μL primary antibody to MEF2 (1:500 in 3% normal goat serum; SantaCruz) for one hour. Following washes in PBS, coverslips were inverted onto parafilm spotted with 100 μL AlexaFluor 647 (1:2000 in 3% normal goat serum; Invitrogen) for one hour in the dark. Coverslips were then washed with PBS and inverted onto glass slides with Prolong Gold Antifade reagent (Invitrogen), allowed to dry, sealed, and fluorescently visualized on a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope. For studies measuring the number of nuclei per MHC positive cell, cells were prepared as detailed above. After the cells were fixed and permeabilized, cover slips were incubated in MF-20 (1:500 in 3% BSA) for two hours, washed extensively and then incubated with donkey anti-mouse-FITC (1:500, Santa Cruz) for 2 hours. Cover slips were extensively washed before the addition of Hoechst (10 μg/ml) for two minutes and mounted as above.

2.6 mAKAP Adenoviral Expression and Analysis

C2C12 cells were incubated with either control adenovirus (AdenoTetR, Clontech) or mAKAP 245-585-Myc (Clontech), described previously, for two days in growth media prior to the induction of differentiation. Fresh differentiation media was then added without adenovirus[26]. Phase contrast images and cell lysates prepared as described above were taken at 1 day intervals.

3. Results

3.1 mAKAP and MEF2 Expression Show a Parallel Increase During Myogenic Differentiation

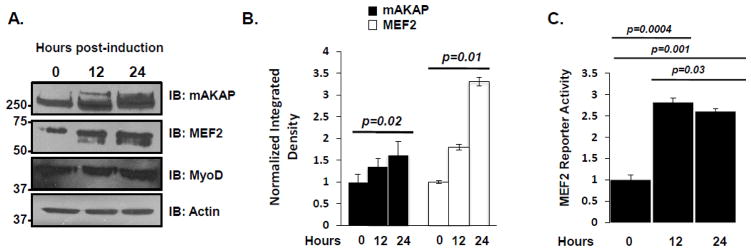

The dynamics of mAKAP expression during myogenic differentiation have not been fully investigated. To address this question, soluble lysates of C2C12 cells taken at 0, 12, and 24 hours post-induction of differentiation were immunoblotted with antibodies to mAKAP, MEF2, and MyoD. Both mAKAP and MEF2 protein increased within the first 24 hours after induction of differentiation (Figure 1A). Quantification of this result is shown in Figure 1B. This increase in protein corresponded with an increase in MEF2 activity over the same time. Utilizing a MEF2 reporter adenovirus to monitor MEF2 activity, we detected a three-fold increase in reporter activity within the first 12 hours of differentiation (Figure 1B). These results show that mAKAP and MEF2 expression are upregulated during differentiation, and that this increase in protein expression correlates with an increase in MEF2 activity.

Figure 1. mAKAP and MEF2 expression show a parallel increase during myogenic differentiation.

(A) C2C12 myoblasts were washed with PBS extensively before the addition of differentiation media. Cell lysate was collected at the time points indicated and proteins were analyzed by immunoblot. n=3. (B) Quantification of the western blots shown in A, normalizing the actin. n=3. (C) C2C12 myoblasts were infected with an adenoviral MEF2 luciferase reporter and β-galactosidase. The resulting transcriptional activity was read at the times indicated. Normalized luciferase values were obtained by dividing the luciferase value by the β-galactosidase control value. n=3. Data shown are mean SEM from three representative experiments.

3.2 mAKAP/MEF2 Interact in Differentiating C2C12 Myoblasts and Differentiated Myotubes

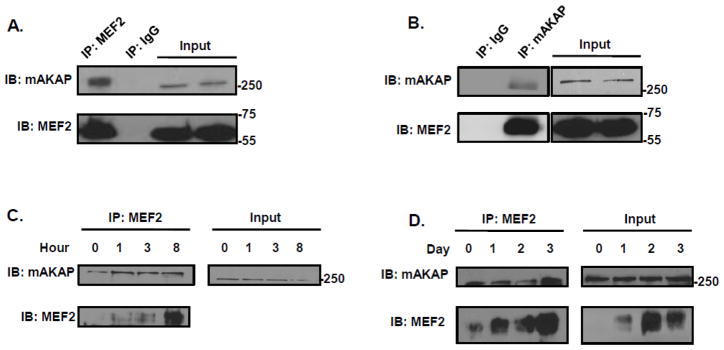

Since both MEF2 and mAKAP protein expression increased in parallel during differentiation, and our previous work found mAKAP complexes regulate the activity of several transcription factors in cardiac muscle, we asked if MEF2 could also be associated with the scaffold[26, 28, 31]. Interestingly, mAKAP was found in MEF2 immunoprecipitates isolated from undifferentiated C2C12 myoblasts cultured in Growth Media, but not with control IgG (Figure 2A). The converse experiment with a mAKAP antibody confirmed these two proteins are located in the same signaling complex (Figure 2B). As expected, increased MEF2/mAKAP association was detected by co-immunoprecipitation using cells cultured in Differentiation Media (Figures 2C & D), consistent with the increased expression of these proteins in the cells. Taken together, these results show that the mAKAP scaffold forms a complex with MEF2 and that this interaction occurs in both proliferative and differentiating C2C12 cells.

Figure 2. mAKAP binds MEF2 in proliferating and differentiating C2C12 cells.

(A) MEF2 was immunoprecipitated from C2C12 myoblast cell lysates using an antibody that recognizes all the known isoforms of the transcription factor. mAKAP binding was demonstrated by immunoblot. n=3 (B) The mAKAP complex was immunoprecipitated from C2C12 myoblast cells using an antibody specific for the AKAP. MEF2 association was determined using an antibody that recognizes all isoforms of MEF2. n=3. (C &D) MEF2 was immunoprecipitated during a short (C) and long (D) time course of C2C12 differentiation using an antibody that recognizes all isoforms of MEF2. Differentiation of C2C12 cells was induced by incubating the cells in differentiation media for the indicated period of time. MEF2 was immunoprecipitated and mAKAP association was determined by immunoblot. (n=3).

3.3 MEF2 Binds Directly to mAKAP

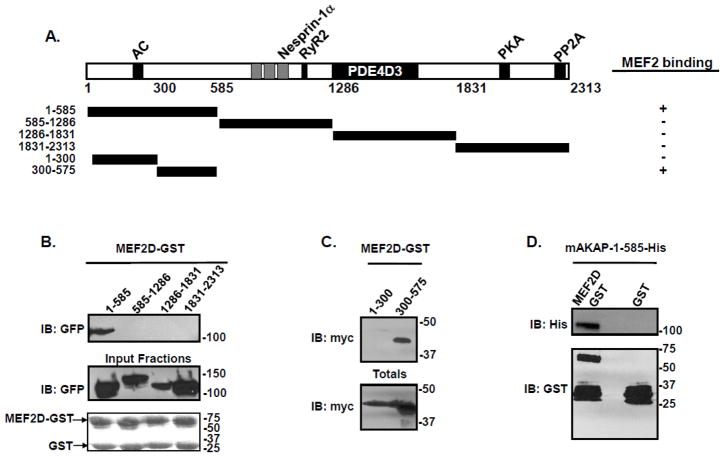

Next, we mapped the domain on mAKAP that governs the binding to MEF2. Constructs encoding four mAKAP fragments were expressed in HEK293 cells. A schematic of truncations and fragments used for these experiments is shown (Figure 3A). Lysates from these cells were incubated with MEF2D-GST bound to agarose beads, and binding was visualized by immunoblot. As shown in Figure 3B, binding was exclusive to the first 585 amino acids of mAKAP. The relevant region on mAKAP was further specified using smaller fragments of mAKAP. Amino acids 1-300 and 300-575 of mAKAP were transfected into HEK293 cells and lysates incubated with MEF2D-GST beads, revealing that amino acids 300-575 of mAKAP mediate the binding between the scaffolding protein and MEF2 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. MEF2 directly binds amino acids 300-375 on mAKAP.

(A) Schematic diagram of the mAKAP fragments used for pulldown assays. (B) MEF2D-GST beads were incubated with HEK293 cell lysates transfected with the indicated mAKAP fragments. After extensive washing, association of the mAKAP fragments was visualized by immunoblot using a GFP antibody. Total protein expression is shown in the middle panel while protein stains of the MEF2D-GST fusion protein is shown in the lower panel. n=3. (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with myc-tagged mAKAP fragments encompassing amino acids 1-300, or 300-575. Cell lysate was isolated and subjected to pulldown assay using GST beads charged with MEF2D. Association of the mAKAP fragment was demonstrated by immunoblot using a myc antibody. Total protein expression is shown in the lower panel. n=3. (D) Bacterially purified His-tagged mAKAP-1-585 was incubated with either MEF2D-GST beads or GST control, and association of mAKAP was visualized by immunoblot using an antibody that recognized the His tag on the mAKAP fragment. The lower panel is a western blot of the GST-fusion proteins used. n=4.

Given that AKAPs exert their effects on signaling through both direct and indirect protein interactions, it was important to know whether MEF2 and mAKAP associated directly or through an adapter protein. Purified MEF2D-GST was incubated with His-tagged mAKAP-1-585 purified from bacteria and analysis of binding was shown by immunoblot. Figure 3D illustrates the direct association between mAKAP and MEF2D. Taken together, these experiments show that MEF2D binds mAKAP directly via an N-terminal domain on the scaffold.

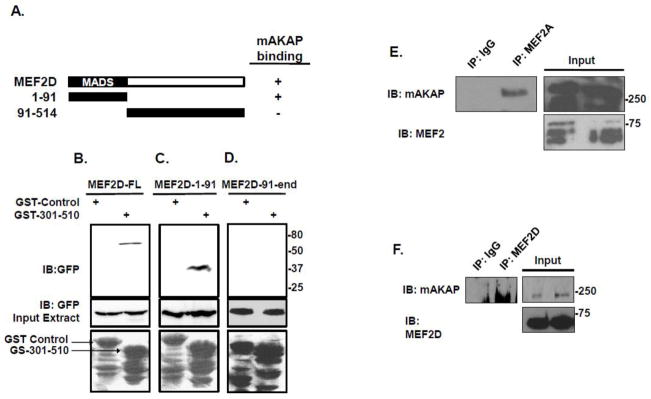

3.4 mAKAP Binds the Conserved DNA Binding Domain of MEF2

MEF2 contains a DNA-binding domain (amino acids 1-91) that is common among MEF2 isoforms, and a non-conserved transactivation domain comprising the remainder of the protein. It has been shown that protein phosphatase 1 binds to both the DNA-binding domain as well as the C-terminal region of MEF2[15]. In contrast, HDAC/MEF2 interactions are achieved via a short sequence spanning the DNA-binding domain of MEF2 [29]. In order to map the mAKAP binding region on MEF2, lysates from HEK293 cells expressing GFP-tagged fusion proteins containing full-length MEF2D, the DNA-binding domain of MEF2D (amino acids 1-91), or the transactivation domain of MEF2D were incubated with a GST-tagged mAKAP/MEF2 binding peptide (GST-mAKAP-301-510). Analysis of the pulldowns by immunoblot revealed that full-length MEF2D as well as the DNA-binding domain of MEF2 both associate with mAKAP (Figure 4B, C), while the transactivation domain did not (Figure 4D). Because this domain is 95% conserved among the four MEF2 proteins, it is likely that other MEF2 isoforms should bind mAKAP as well[30]. Accordingly, we found that both endogenous MEF2A (Figure 4E) and MEF2D (Figure 4F) co-immunoprecipitate with mAKAP from C2C12 cells.

Figure 4. mAKAP binds the first 91 amino acids of MEF2.

(A) Schematic diagram depicting the MEF2 expression fragments used for this study. (B) The MEF2 binding fragment of mAKAP (301-510) was expressed as a GST fusion protein. Beads charged with either the mAKAP fragment or control protein were incubated with HEK293 cell lysates transfected with either GFP-tagged full length MEF2 (B), amino acids 1-91 of MEF2 (C), or amino acids 91-410 (D). Association was visualized by immunoblot using an antibody that recognized the GFP tag on the fragments. Total protein expression is shown in the middle bands while a protein stain of the GST fragments used is shown in the lower panel. n=3. (E) MEF2A was immunoprecipitated from C2C12 cells and association of mAKAP was demonstrated by western blot. (F)

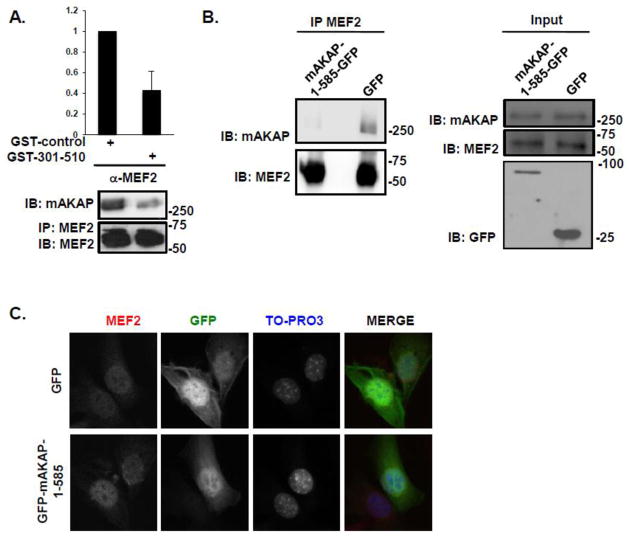

3.5 Disruption of the mAKAP/MEF2 interaction

Having detected mAKAP/MEF2 complexes during C2C12 differentiation, we considered that the association might regulate MEF2 activity. To test this hypothesis, we conducted experiments to disrupt binding between the two proteins both in vitro and in vivo. We first determined that a GST-fusion protein consisting of the MEF2 binding domain on the AKAP (amino acids 301-510) would serve as a competitive inhibitor of mAKAP/MEF2 binding in vitro. Addition of the bacterial-expressed mAKAP fragment to cell lysates containing mAKAP and MEF2 significantly inhibited the co-immunoprecipitation of the endogenous proteins (Figure 5A). Importantly, ectopic expression of GFP-mAKAP-1-585 in C2C12 cells was sufficient to prevent co-immunoprecipitation of mAKAP with MEF2 (Figure 5B). Furthermore, we detected no change in MEF2 localization under these conditions (Figure 5C). These results suggest that the mAKAP/MEF2 interaction can be disrupted using this competing fragment and disruption does not alter MEF2 localization.

Figure 5. MEF2 is displaced from mAKAP in vitro and in vivo after disruption of the complex.

(A) GST-mAKAP-301-510 or GST-control fusion proteins were incubated with extract isolated from C2C12 cells cultured in differentiation media for 24 hours prior to immunoprecipitation of endogenous MEF2/mAKAP complexes using a MEF2 antibody that recognizes all isoforms of the transcription factor. The amount of mAKAP in the immunoprecipitate was normalized to MEF2. n=3. (B) C2C12 cells were transfected with GFP-tagged mAKAP-1-585 or GFP alone. MEF2 was immunoprecipitated and association of mAKAP was determined by immunoblot. Input (middle panel) represents 20% of total extract used for immunoprecipitation. Lower panel illustrates expression of the GFP fragments. n=3. (C) Expression patterns of GFP and MEF2 after transfection with either GFP-tagged mAKAP-1-585 (lower panels) or GFP alone (upper panels) in C2C12 myoblasts. n=3.

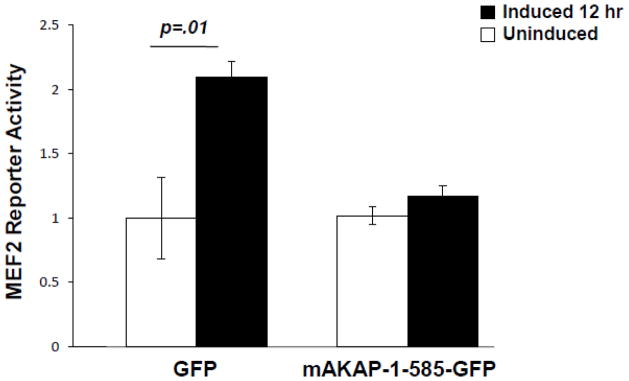

3.6 MEF2 Anchoring to mAKAP is Critical for Transcriptional Activity

Expression of the MEF2 binding domain on mAKAP to disrupt mAKAP/MEF2 binding allowed us to ask whether MEF2 anchoring to the AKAP was important for MEF2 transcriptional activity. C2C12 cells were infected with the MEF2-luciferase and control adenoviruses 18 hours prior to transfection of GFP-mAKAP-1-585 or GFP control expression plasmids. Luciferase assays were performed before and after the induction of differentiation. As shown in Figure 6, displacement of MEF2 from mAKAP prevented the increase in MEF2 activity seen after 12 hours of differentiation. This result suggests that association of MEF2 with the anchoring protein is required for efficient activation of gene transcription during myogenic differentiation.

Figure 6. MEF2 tethering to mAKAP is required for transcriptional activity.

C2C12 cells were infected with an adenoviral MEF2 luciferase reporter and β-galactosidase, and then transfected with either GFP alone or GFP-tagged mAKAP-1-585 as described in the Methods section. The resulting transcriptional activity was read before and 12 hours after induction of differentiation. Normalized luciferase values were obtained by dividing the luciferase value by the β-galactosidase value. Data shown are mean ± SEM from three experiments, p-values as noted.

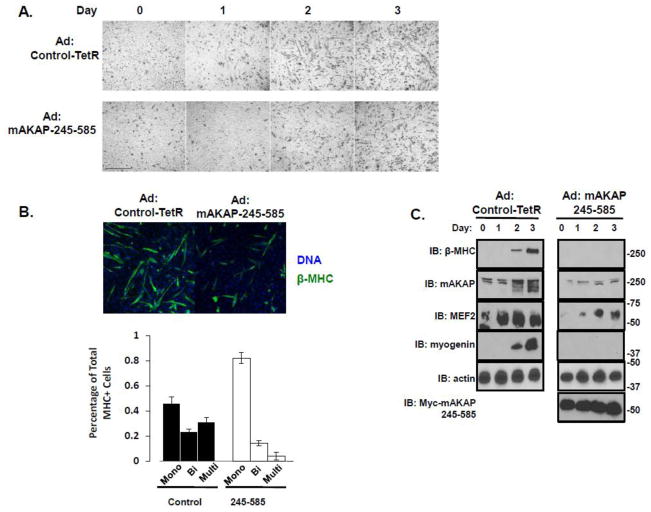

3.7 MEF2 Anchoring to mAKAP is Necessary for Differentiation

Having demonstrated that mAKAP/MEF2 association was critical for MEF2 luciferase reporter activity, we next asked whether dissociating MEF2 from mAKAP would affect myogenic differentiation. We employed adenoviral expression of the disrupting fragment (Myc-mAKAP-245-585), since transient transfection did not allow persistent expression over the full course of differentiation, and monitored myobloast differentiation by the elongation of the myoblasts, formation of multinucleated myotubes and accumulation of markers for skeletal muscle differentiation. Using phase-contrast imaging, we found that continuous disruption of MEF2/mAKAP interactions during myogenic differentiation was sufficient to significantly attenuate the elongation of C2C12 cells that occurs 3–4 days after the induction of differentiation (Figure 7A, lower panels). As a more quantitative measurement of differentiation, we counted the formation of multinucleated myotubes. Cells were incubated in differentiation media for three days, and then stained for the differentiation marker β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) as well as Hoechst to counterstain the nuclei. The number of mono-nucleated, bi-nucleated and multinucleated cells was determined. Appropriately, only 11% of the β-MHC positive cells were bi-nucleated or multinucleated in cells expressing the 245-585 adenovirus compared to 60% of the cells treated with control adenovirus (Figure 7B). This reduction of cell fusion was also associated with reduced the expression of several markers for skeletal muscle differentiation. Disruption of the MEF2-mAKAP interaction prevented expression of a MEF2 target, the contractile protein β-myosin heavy chain (Figure 7C)[31–33]. Expression of myogenin, a later muscle-specific transcription factor, was also delayed (Figure 7C). Finally, as MEF2 is autoregulated and promotes its own increase in protein expression, overall expression of MEF2 was decreased as well. The data presented show that when MEF2 is disrupted from the mAKAP complex, the overall commitment to myogenic differentiation is attenuated.

Figure 7. MEF2 tethering to mAKAP is required for efficient myogenic differentiation.

(A) C2C12 cells infected with either a control adenovirus (top row) or adenovirus expressing myc-tagged mAKAP-245-585 were imaged over four days to monitor the development of myotubes. Scale bar = 20 μm. n=3. (B) C2C12 cells were treated as describe in A. After three days in differention media, the cells were stained with MHC and Hoechst. The number of nuclei per β-MHC positive cell was determined from three separate experiments. A total of 304 cells were counted from the 245-585 expressing cells while 367 cells were counted from the control. (C) Immunoblot analysis of differentiation markers from lysates prepared from C2C12 cells infected with either control adenovirus or adenovirus expressing myc-mAKAP-245-585 over the four days of imaging described in (A). n=3.

4. Discussion

As a key element in the induction of skeletal muscle differentiation, MEF2 is regulated by several signaling networks, extensive post-translational modification, and direct protein-protein interactions[10–12, 15–19, 34]. Here we reveal a novel regulatory factor for MEF2, the A-kinase anchoring protein mAKAP. Amino acids 300-575 of mAKAP bind the transcription factor, and over-expression of this domain is sufficient to disrupt the interaction. Importantly, blocking mAKAP/MEF2 interaction abrogated the differentiation-induced increase in MEF2-luciferase activity and the concomitant increase in MEF2-regulated skeletal muscle genes as well as the morphologic changes associated with differentiation (Figure 7A, B). Thus, this work demonstrates the importance of the AKAP scaffold for the regulation of MEF2 activity and shows that mAKAP association with MEF2 is required for the differentiation of skeletal muscle precursor cells.

Previous work on the mAKAP complex has demonstrated that it serves to scaffold several signaling proteins at the nuclear envelope including PKA, PDE4D3, ERK5, PP2B, and PP2A[21, 24, 25, 27, 28]. Of these, PKA, ERK5, and PP2B are known regulators of MEF2 activity as well as myogenic differentiation[11, 12, 14]. Therefore it is conceivable that the anchoring protein is functioning to integrate the upstream regulators with the downstream effector, MEF2. Given that targeted disruption of the mAKAP/MEF2 complex blunted MEF2 transcriptional activity, we hypothesize that this prevented these signaling enzymes from directly regulating MEF2. However, further studies are needed to determine what post-translational modifications are mediated by mAKAP/MEF2 binding.

MEF2 is the third transcription factor reported to bind mAKAP; NFATc3 and HIF1-α are also regulated by the scaffold[28, 31]. These studies found that NFATc3 and HIF1-α conditionally associate with the mAKAP complex, are modified by mAKAP-bound effector molecules, and are subsequently released in active form to shuttle into the nucleus. Accordingly, MEF2/mAKAP association was also increased during myocyte differentiation, suggesting a similar mechanism may play a role in the regulation of MEF2 during skeletal muscle differentiation.

The transition from proliferating myoblasts to terminally differentiated muscle fibers requires the sequential modification of MEF2 beginning with the disruption of a MEF2/HDAC inhibitory complex, and ending with the formation of a transcriptional complex composed of MyoD, MEF2, and pRb[35–37]. Importantly, sustained disruption of MEF2 from the mAKAP scaffold was sufficient to block myogenic differentiation, resulting in cells that failed to elongate and fuse, as demonstrated by cellular morphology and percentage of multinucleated cells. At present, exactly what point of this process is affected by complex disruption is unknown, but given the observed changes to the MEF2 transcriptional response within the first day of differentiation, we hypothesize that it involves the early mechanisms of MEF2 activation. Additionally, it follows that genetic targets of MEF2 would be either delayed or absent since we observed blunted MEF2 transcriptional activity. Specifically, β-MHC, a component of the contractile apparatus, was reduced during differentiation. This is most likely attributed to less transcription at the β-MHC gene, since it is a known target of MEF2 transcription[31–33].

In summary, we have identified a novel interaction between the transcription factor MEF2 and the scaffolding protein mAKAP. Importantly, this interaction is required for proper stimulation of MEF2 transcription, as well as the efficient differentiation of skeletal myoblasts into myotubes. This work not only increases our understanding of MEF2 regulation, but also has implications for a broader understanding of MEF2 transcriptional activity. For example, both MEF2 and mAKAP play pivotal roles in the induction of cardiac hypertrophy, suggesting the scaffolding protein may regulate MEF2 activity in this system as well, and that alteration of this association might be useful for preventing hypertrophy[24, 28, 41]. Furthermore, the MEF2/mAKAP interaction may also occur in hippocampal neurons, where MEF2 is important for post-synaptic gene transcription[19].

Highlights.

MEF2 and mAKAP interact directly in C2C12 cells during myogenic differentiation

This interaction is required for transcriptional activity of MEF2

Disruption of the interaction halts myogenic differentiation

Disruption of the interaction blunts expression of MEF2 target genes

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge John Redden, Arpita Singh, and Andrew Le for helpful discussion of this work. This work contains data from the doctoral thesis of Maximilian Vargas (UCHC, Farmington, CT, USA).

6. Funding

This work was funded, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL82705 (K.L.D.-K.) and HL075398 (M.S.K).

Abbreviations

- mAKAP

muscle specific A-kinase anchoring protein

- MEF2

myocyte enhancer factor 2

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PDE4D3

phosphodiesterases type 4D3

- ERK5

big mitogen-activated protein kinase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wakelam MJ. The fusion of myoblast. Biochem J. 1985:1–12. doi: 10.1042/bj2280001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu YT, Breibart RE, Smoot LB, Lee YJ, Mahdavi V, Nadal-Ginard B. Human myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2 comprises a group of tissue-restricted MADS box transcription factors. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:1783–1798. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott JC, Cardoso MC, Yu YT, Andres V, Leifer D, Krainc D, Lipton SA, Nadal-Ginard B. hMEF2C gene encodes skeletal muscle- and brain-specific transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2564–2577. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitbart RE, Liang CS, Smoot LB, Laheru DA, Mahdavi V, Nadal-Ginard B. A fourth human MEF2 transcription factor, hMEF2D, is an early marker of the myogenic lineage. Development. 1993;118:1095–1106. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lilly B, Zhao B, Ranganayakulu G, Paterson BM, Schulz RA, Olson EN. Requirement of MADS domain transcription factor D-MEF2 for muscle formation in Drosophila. Science. 1995;267:688–693. doi: 10.1126/science.7839146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bour BA, O’Brien MA, Lockwood WL, Goldstein ES, Bodmer R, Taghert PH, Abmayr SM, Nguyen HT. Drosophila MEF2, a transcription factor that is essential for myogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:730–741. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molkentin JD, Olson EN. Combinatorial control of muscle development by basic helix-loop-helix and MADS-box transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9366–9373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ornatsky OI, Andreucci JJ, McDermott JC. A dominant-negative form of transcription factor MEF2 inhibits myogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33271–33278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregoire S, Xiao L, Nie J, Zhang X, Xu M, Li J, Wong J, Seto E, Yang XJ. Histone deacetylase 3 interacts with and deacetylates myocyte enhancer factor 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1280–1295. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00882-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregoire S, Tremblay AM, Xiao L, Yang Q, Ma K, Nie J, Mao Z, Wu Z, Giguere V, Yang XJ. Control of MEF2 transcriptional activity by coordinated phosphorylation and sumoylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4423–4433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du M, Perry RL, Nowacki NB, Gordon JW, Salma J, Zhao J, Aziz A, Chan J, Siu KW, McDermott JC. Protein kinase A represses skeletal myogenesis by targeting myocyte enhancer factor 2D. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2952–2970. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00248-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato Y, Zhao M, Morikawa A, Sugiyama T, Chakravortty D, Koide N, Yoshida T, Tapping RI, Yang Y, Yokochi T, Lee JD. Big mitogen-activated kinase regulates multiple members of the MEF2 protein family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18534–18540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu H, Naya FJ, McKinsey TA, Mercer B, Shelton JM, Chin ER, Simard AR, Michel RN, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Williams RS. MEF2 responds to multiple calcium-regulated signals in the control of skeletal muscle fiber type. EMBO J. 2000;19:1963–1973. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKinsey TA, Zhang CL, Olson EN. Activation of the myocyte enhancer factor-2 transcription factor by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-stimulated binding of 14-3-3 to histone deacetylase 5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14400–14405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260501497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry RL, Yang C, Soora N, Salma J, Marback M, Naghibi L, Ilyas H, Chan J, Gordon JW, McDermott JC. Direct interaction between myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) and protein phosphatase 1alpha represses MEF2-dependent gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3355–3366. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00227-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao X, Sternsdorf T, Bolger TA, Evans RM, Yao TP. Regulation of MEF2 by histone deacetylase 4- and SIRT1 deacetylase-mediated lysine modifications. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8456–8464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8456-8464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong X, Tang X, Wiedmann M, Wang X, Peng J, Zheng D, Blair LA, Marshall J, Mao Z. Cdk5-mediated inhibition of the protective effects of transcription factor MEF2 in neurotoxicity-induced apoptosis. Neuron. 2003;38:33–46. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han J, Jiang Y, Li Z, Kravchenko VV, Ulevitch RJ. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature. 1997;386:296–299. doi: 10.1038/386296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shalizi A, Gaudilliere B, Yuan Z, Stegmuller J, Shirogane T, Ge Q, Tan Y, Schulman B, Harper JW, Bonni A. A calcium-regulated MEF2 sumoylation switch controls postsynaptic differentiation. Science. 2006;311:1012–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch EJ, Jones BW, Scott JD. Networking with AKAPs: context-dependent regulation of anchored enzymes. Mol Interv. 2010;10:86–97. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapiloff MS, Schillace RV, Westphal AM, Scott JD. mAKAP: an A-kinase anchoring protein targeted to the nuclear membrane of differentiated myocytes. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 16):2725–2736. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michel JJ, Townley IK, Dodge-Kafka KL, Zhang F, Kapiloff MS, Scott JD. Spatial restriction of PDK1 activation cascades by anchoring to mAKAPalpha. Mol Cell. 2005;20:661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pare GC, Easlick JL, Mislow JM, McNally EM, Kapiloff MS. Nesprin-1alpha contributes to the targeting of mAKAP to the cardiac myocyte nuclear envelope. Exp Cell Res. 2005;303:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodge KL, Khouangsathiene S, Kapiloff MS, Mouton R, Hill EV, Houslay MD, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. mAKAP assembles a protein kinase A/PDE4 phosphodiesterase cAMP signaling module. EMBO J. 2001;20:1921–1930. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodge-Kafka KL, Soughayer J, Pare GC, Carlisle Michel JJ, Langeberg LK, Kapiloff MS, Scott JD. The protein kinase A anchoring protein mAKAP coordinates two integrated cAMP effector pathways. Nature. 2005;437:574–578. doi: 10.1038/nature03966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapiloff MS, Piggott LA, Sadana R, Li J, Heredia LA, Henson E, Efendiev R, Dessauer CW. An adenylyl cyclase-mAKAPbeta signaling complex regulates cAMP levels in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23540–23546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.030072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pare GC, Bauman AL, McHenry M, Michel JJ, Dodge-Kafka KL, Kapiloff MS. The mAKAP complex participates in the induction of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy by adrenergic receptor signaling. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5637–5646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodge-Kafka KL, Bauman A, Mayer N, Henson E, Heredia L, Ahn J, McAvoy T, Nairn AC, Kapiloff MS. cAMP-stimulated protein phosphatase 2A activity associated with muscle A kinase-anchoring protein (mAKAP) signaling complexes inhibits the phosphorylation and activity of the cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase PDE4D3. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11078–11086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.034868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu J, McKinsey TA, Zhang CL, Olson EN. Regulation of skeletal myogenesis by association of the MEF2 transcription factor with class II histone deacetylases. Mol Cell. 2000;6:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black BL, Olson EN. Transcriptional control of muscle development by myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) proteins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1998;14:167–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN, Lowell BB, Bassel-Duby R, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature. 2002;418:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan T, Jiang H, Li H, DiMario JX. Inhibition of ryanodine receptor 1 in fast skeletal muscle fibers induces a fast-to-slow muscle fiber type transition. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6175–6183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karasseva N, Tsika G, Ji J, Zhang A, Mao X, Tsika R. Transcription enhancer factor 1 binds multiple muscle MEF2 and A/T-rich elements during fast-to-slow skeletal muscle fiber type transitions. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5143–5164. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5143-5164.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinev D, Jordan BW, Neufeld B, Lee JD, Lindemann D, Rapp UR, Ludwig S. Extracellular signal regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) is required for the differentiation of muscle cells. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:829–834. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKinsey TA, Zhang CL, Lu J, Olson EN. Signal-dependent nuclear export of a histone deacetylase regulates muscle differentiation. Nature. 2000;408:106–111. doi: 10.1038/35040593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novitch BG, Spicer DB, Kim PS, Cheung WL, Lassar AB. pRb is required for MEF2-dependent gene expression as well as cell-cycle arrest during skeletal muscle differentiation. Curr Biol. 1999;9:449–459. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Falco G, Comes F, Simone C. pRb: master of differentiation. Coupling irreversible cell cycle withdrawal with induction of muscle-specific transcription. Oncogene. 2006;25:5244–5249. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]