Abstract

Aims

Prior research has suggested that problematic alcohol and drug use are related to risky sexual behaviors, either due to trait-level associations driven by shared risk factors such as sensation seeking, or by state-specific effects, such as the direct effects of substance use on sexual behaviors. Although the prevalence of both high-risk sexual activity and alcohol problems decline with age, little is known about how the associations between substance use disorder symptoms and high-risk sexual behaviors change across young adulthood.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Using a community sample (n = 790) interviewed every three years from age 21 to age 30, we tested trait- and state-level associations among symptoms of alcohol and drug abuse and dependence and high-risk sexual behaviors across young adulthood using latent growth curve models.

Measurements

We utilized diagnostic interviews to obtain self-report of past-year drug and alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms. High-risk sexual behaviors were assessed with a composite of four self-reported behaviors.

Findings

Results showed time-specific associations between alcohol disorder symptoms and risky sexual behaviors (r =.20, p < .001), but not associations between their trajectories of change. Conversely, risky sexual behaviors and drug disorder symptoms were associated only at the trait level, not the state level, such that the levels and rate of change over time of both were correlated (r = .35, p < .001).

Conclusions

High-risk sexual behaviors during young adulthood seem to be driven both by trait and state factors, and intervention efforts may be successful if they are either aimed at high-risk individuals, or if they work to disaggregate alcohol use from risky sexual activities.

Introduction

Problematic alcohol and drug use covary with risky sexual behaviors among both adolescents and adults (e.g. [1-7]). Interventions, such as Project ALERT (a school-based drug prevention program), reduced the likelihood of risky sexual behaviors up to 7 years later in part through reductions in alcohol and drug use [1]. Prior literature focused on adolescents, and little is known about how associations between substance use and risky sexual behavior may change across young adulthood. The transition to adulthood is marked by dramatic increases in freedoms and responsibilities that occur at the same time that an individual’s ability to self-regulate is still emerging [2, 3]. This developmental stage is also marked by peaks in alcohol and drug use disorders (12.5% meet diagnostic criteria for a past-year alcohol or drug use disorder) [4] and diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs; [5]), followed by declines in the prevalence of both (save HIV [6]). Yet how the associations between substance use disorders and risky sexual behaviors unfold across young adulthood remains unclear.

State- and Trait-level Theories of Sexual Risk Behaviors and Substance Use

Two theories hypothesized that alcohol use may be connected to high-risk sexual behaviors because states of intoxication lead directly to high-risk sexual behaviors. Alcohol myopia theory [7] hypothesizes that alcohol consumption leads to an over-focus on the short-term rewards of sex and a downplaying of the potential negative consequences, which results in poor sexual decision making [8-10]. Other research suggests that individuals who believe that alcohol will enhance sexual experiences and promote risky sexual behavior are more likely to engage in these behaviors when drinking alcohol [11], in part because they expect alcohol to provide a viable excuse for certain risky sexual behaviors that are not socially sanctioned (see [12] for review). However, little of the research on myopia or expectancy has focused on the impact of the use of drugs other than alcohol on risky sexual activity.

On the other hand, trait theories hypothesize that the associations between high-risk sexual activity and substance use are explained by individual differences that predict both behaviors, such as neuroticism, surgency, sensation seeking, or impulsivity [13]. Other theories have suggested that the co-occurrence of risky behaviors represents a broad syndrome of “problem behaviors” (e.g. [14]), implying that the covariation among alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior may result largely from a tendency to engage in multiple high-risk behaviors.

Covariation of Substance Use and Sex Risk Behaviors Across Young Adulthood

Latent trajectory models [15], which model how variability in observations across time can be explained as a function of an underlying developmental trend (or trajectory), may be used to test both trait and state hypotheses (see [16] and [17] for similar applications of these models). Individual difference, or trait models, would predict that covariation between alcohol and drug use disorder symptoms and risky sexual behaviors at a given age is observed because the underlying developmental trajectories of both are correlated across young adulthood, in the same way their trajectories are associated across adolescence (e.g. [18]), because of an underlying individual difference that consistently influences the general trajectory of risk behaviors. Conversely, state models predict that engaging in risky substance use at a given age would be associated with greater engagement in risky sex (but perhaps only for those with higher levels of sexual expectancies) at that same age, which would be reflected in covariation between substance use and sex risk behaviors above and beyond that predicted by the developmental trajectory. Although these time-specific (i.e. within year) associations do not directly capture event-level associations, they would be expected to be influenced by event-level associations, as well as other factors that are specific to that time point (such as social contexts or norms). The state and trait models provide complimentary, not competing, hypotheses about the development of risky sexual behaviors and substance use disorder symptoms across young adulthood. No prospective research that we are aware of has addressed the covariance of risky sexual behaviors and alcohol and drug use disorder symptoms in samples older than age 21.

Parsing out these associations across young adulthood – how much is due to associations between trajectories of substance use and sex risk behaviors at the trait levels, and how much is due to state-specific covariation independent of trajectories – has important implications for intervention and prevention efforts. Support for trait models of risk could aid in identification of high-risk individuals who could be targeted for intervention, and provide information about how their risk may be expected to change during a developmental period of decline in risk activity. Conversely, understanding how risk behaviors are associated independent of trajectories could allow age-dependent targeting of prevention efforts aimed at dampening the more immediate effects of alcohol or drug involvement on risky sexual behaviors, or aimed at the shared social situations and contexts that may make both more likely.

Method

Sample

The sample was from the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP), recruited in 1985 from 18 Seattle elementary schools that overrepresented students drawn from high-crime neighborhoods (N = 1053). SSDP included a multicomponent intervention in the elementary grades, consisting of teacher training, parenting classes, and social competence training for children. Although prior analyses have found differences in the levels and prevalence of outcomes between SSDP intervention groups, with respect to the current analyses we found little evidence of differences in relationships among variables (i.e., covariance matrices) across study conditions. From this population, 808 students (77%) consented to participate in the longitudinal study and constituted the SSDP sample. Analyses included all participants who completed one or more surveys across four waves of data collected at ages 21, 24, 27, and 30 (1996, 1999, 2002, and 2005; N = 790; 98% of the total sample). The dataset was 50% female; and was 47% Caucasian, 26% African American, 22% Asian American, and 5% Native American. Around 50% of the sample experienced childhood poverty, as measured by eligibility for the federal free and reduced-price school lunch program. SSDP retention was 91% at minimum through the adult waves. Detailed summaries of SSDP can be found in Hawkins et al. [19, 20]. Data collection procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the University of Washington.

Measures

Alcohol and drug use disorder symptoms

Self-report of 11 alcohol and drug abuse, and dependence symptoms obtained at ages 21, 24, 27, and 30 were assessed with a modified version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) [19, 21-23], which measured disorder criteria specified by the DSM-IV [24]. The DIS has been used frequently in studies of psychiatric disorders among adults drawn from the general population and has been demonstrated to be valid and reliable [25-28]. Two separate scores for alcohol and drug abuse and dependence symptoms were computed by summing the number of criteria met in the past year at each adult wave (mean α = .86). The most prevalent symptoms varied across substance and age. The most common alcohol use disorder symptom at age 21 was increased tolerance; at age 24 it was more use than was intended; and at ages 27 and 30 it was desire or unsuccessful efforts to control use. The most common drug use disorder symptom at ages 21, 24, and 27 was hazardous use (e.g., while driving an automobile); and at age 30 it was desire or unsuccessful efforts to control use.

High-risk sexual behaviors

Building on Guo et al. [29], this index summed four dichotomous indicators of self-reported risk in the past year: (a) having had more than one sex partner, (b) inconsistent condom use and not married, (c) sex outside of a steady relationship, and (d) exchanged money or drugs for sex (coded 0-4). These were derived from the following items: “In the past 12 months, how many [men/women] have you had sex with?” (coded ≤1, ≥2, with 33% reporting >2 partners at age 21, 22% at age 30); In the past year, how much of the time was latex protection used when you had sexual intercourse [if not married]?” (coded Always, < Always, with 54% reporting <Always at age 21, 35% at age 30); “Do you currently have any steady romantic relationships [if sexually active in past year]?” (coded Yes, No, with 29% answering no at age 21, 19% at age 30); “Have you ever given money or drugs to someone in order to have sex with him or her [in the past year]? (coded No, Yes); “Has anyone ever given you money or drugs in order to have sex with you [in the past year]? (coded No, Yes), with 2.6% answering yes to either at age 21, and 3% at age 30. We used confirmatory factor analysis to test the associations between these different risk behaviors at each age. This model fit the data well (CFI = .92, RMSEA = .05) and standardized factor loadings ranged from λ = .61 (for d) to λ = .82 (for a) and were invariant across time. This suggested that combining across the different risk behaviors was appropriate even though they may differ in their potential severity and prevalence.

Analytic Strategy

All initial analyses were conducted using MPlus 5.1 [30] with the MLR estimator, accounting for missing data by using full information maximum-likelihood estimation [31, 32, pp. 363–364]. To test whether varying permutations of each model improved model fit, we used Satorra’s chi-square difference tests for MLR chi-square [33]. Model fit was assessed using a combination of chi-square [34], and several relative fit indices that are transformations of chi-square – including the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) –[34]. Because the sex-risk behavior data was a count variable, we replicated the final model specifying it as a categorical variable with the WLSMV estimator (because residual variances are not estimated for count variables in MPlus) to ensure the model replicated across estimators. For all growth models, the intercept was fixed to age 21, and the linear slope factor represented the rate of change from age 21 to age 30.

Results

All risk behaviors were positively but moderately correlated (r = .14 - .46) within each time period. Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics of risk behaviors. The prevalence of substance use disorder symptoms was relatively modest and decreased over time, with 48% to 29% reporting any alcohol disorder symptoms and 20% to 11% reporting any drug disorder symptoms. The prevalence of sexual risk behaviors was somewhat higher, but also decreased over time from 74% reporting any risky behaviors at age 21 to 51% reporting any behaviors at age 30.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of risk behaviors

| N | M | SD | % Non-zero | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual risk behaviors age 21 | 763 | 1.27 | 1.00 | 73.80 |

| Sexual risk behaviors age 24 | 742 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 62.70 |

| Sexual risk behaviors age 27 | 747 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 60.00 |

| Sexual risk behaviors age 30 | 717 | 0.89 | 1.06 | 50.90 |

| Alcohol symptoms age 21 | 763 | 1.26 | 1.81 | 47.70 |

| Alcohol symptoms age 24 | 752 | 1.09 | 1.78 | 42.80 |

| Alcohol symptoms age 27 | 746 | 0.92 | 1.84 | 32.40 |

| Alcohol symptoms age 30 | 693 | 0.80 | 1.73 | 28.60 |

| Drug symptoms age 21 | 764 | 0.61 | 1.61 | 19.90 |

| Drug symptoms age 24 | 752 | 0.50 | 1.53 | 16.00 |

| Drug symptoms age 27 | 747 | 0.46 | 1.53 | 13.50 |

| Drug symptoms age 30 | 695 | 0.38 | 1.35 | 11.40 |

Note: % Non-Zero refers to the proportion of the sample reporting at least one symptom or risk behavior at that age.

Unconditional Growth Curve Models

Table 2 summarizes the model fit indices for each sequence of univariate growth models and the trivariate parallel process multivariate models.

Table 2.

Model fit statistics for univariate and trivariate models

| χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | BIC | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate growth model | |||||||

| 1 Sex risk latent growth | 22.877 | 5 | 0.942 | 0.932 | 8331.31 | 0.067 | 0.041 |

| 2 Alcohol symptoms latent growth | 2.567 | 5 | 1.000 | 1.013 | 11122.06 | 0.000 | 0.021 |

| 3 Drug symptoms latent growth | 2.993 | 5 | 1.000 | 1.025 | 10337.00 | 0.000 | 0.030 |

| Trivariate growth model | |||||||

| 1 Full model: all parameters freed | 43.985 | 43 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 29204.99 | 0.005 | 0.029 |

| 2 #1 + TV drug and sex at zero | 43.985 | 43 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 29204.99 | 0.005 | 0.029 |

| 3 #1 + TV alcohol and sex at zero | 74.377 | 43 | 0.970 | 0.954 | 29259.93 | 0.030 | 0.032 |

| 4 #1 + TV drug and alcohol at zero | 94.414 | 43 | 0.951 | 0.924 | 29315.29 | 0.039 | 0.037 |

| 5 #2 + Sex and alcohol covariation fixed over time | 46.427 | 46 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 29197.20 | 0.003 | 0.029 |

| 6 #5 + Alcohol and drug covariation fixed over time | 56.621 | 49 | 0.993 | 0.990 | 29212.00 | 0.014 | 0.034 |

| 7 #5 + T1-T3 alcohol and drug covariation fixed over time | 46.526 | 47 | 1.001 | 1.000 | 29195.02 | 0.000 | 0.028 |

All n = 790.

Unconditional univariate growth models

These models all fit the data well (see Table 2). The means and variances of the latent intercepts in all three univariate models, representing levels of sexual risk behaviors, or alcohol or drug symptoms at age 21, were all positive and significant (Msex = 1.25, p < .001; Varsex = .34, p < .001; Mdrug = .61, p < .001; Vardrug = 1.40, p < .001; Malcohol = 1.24, p < .001; Varalcohol = 1.74, p < .001). The means of the latent slopes, representing the rate of change over time in sexual risk or alcohol or drug symptoms from age 21 to age 30, were all negative and significant, with significant interindividual variance (Msex = -.12, p < .001; Varsex = .05, p < .001; Mdrug = -.08, p < .001; Vardrug = .15, p < .001; Malcohol = -.15, p < .001; Varalcohol = .14, p < .001). This indicated that on average, participants decreased in all problem behaviors across young adulthood, but that individuals varied in their rate of decline. For example, the results from the alcohol symptoms model would indicate that at age 21, most participants (i.e. within 1 SD of the mean intercept) reported between 0 and 4.65 symptoms of alcohol abuse or dependence, and over time reported from .42 fewer symptoms (at 1 SD below the mean slope) to .12 more symptoms (at 1 SD above the mean slope) every 3 years. We also tested for quadratic growth (representing changes in the rate of change over time), but for all three variables the quadratic factor had a nonsignificant mean and variance.

The intercept of sex risk behaviors was not significantly correlated with its slope (r = -.18, p > .05), but the intercepts and slopes were negatively correlated for both drug (r = -.61, p < .001) and alcohol (r = -.37, p < .01) symptoms, suggesting that individuals with more alcohol or drug symptoms at the first time point exhibited greater declines across young adulthood.

Trivariate parallel process models

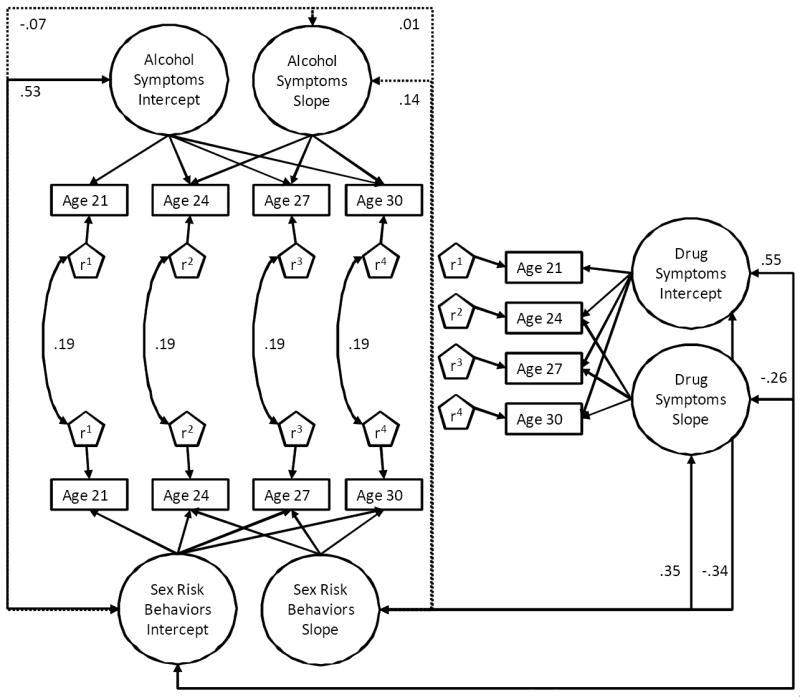

We next combined the three latent growth models into a trivariate parallel process latent growth curve model. We began with a fully unconstrained model, allowing all intercept and slope factors and time-varying residuals to freely correlate. We then tested a sequence of model constraints to determine the most parsimonious model. The final model (whose fit indices are summarized in Table 2) exhibited excellent fit to the data. Table 3 provides a summary of the results of this model, and Figure 1 illustrates the results of model. The final model replicated well with similar fit statistics and estimates when the sex-risk behavior variable was treated as a categorical variable using the WLSMV estimator.

Table 3.

Correlations among the latent growth factors and time-specific residuals

| Latent growth factor correlations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol symptoms intercept | 1.00 | -0.38 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.59 | -0.34 |

| 2. Alcohol symptoms slope | 1.00 | -0.07 | 0.14 | -0.33 | 0.48 | |

| 3. Sex risk behaviors intercept | 1.00 | -0.21 | 0.55 | -0.34 | ||

| 4. Sex risk behaviors slope | 1.00 | -0.26 | 0.35 | |||

| 5. Drug symptoms intercept | 1.00 | -0.62 | ||||

| 6. Drug symptoms slope | 1.00 |

| Time-specific residual correlations | Alcohol symptoms |

| Age 21 | |

| Sex risk behaviors | 0.195 |

| Drug symptoms | 0.288 |

| Age 24 | |

| Sex risk behaviors | 0.195 |

| Drug symptoms | 0.288 |

| Age 27 | |

| Sex risk behaviors | 0.195 |

| Drug symptoms | 0.288 |

| Age 30 | |

| Sex risk behaviors | 0.195 |

| Drug symptoms | -0.009 |

Note: Bolded coefficients are significant, p < .01.

Figure 1.

State- and trait-level associations between alcohol and drug symptoms and risky sexual behaviors

Note: Only standardized pathways between sex risk behaviors and substance use disorders are exhibited for parsimony’s sake; solid lines are significant associations, p < .05. All model covariances estimated are displayed in Table 4.

Trait-level associations among the latent growth factors

At the trait (or latent growth factor) level, the intercept of alcohol symptoms was only associated with sex risk behaviors at its intercept (r = .53, p < .001), not its slope (r = .01, p = .90), while the slope of alcohol symptoms was unrelated to either the intercept (r = -.07, p = .56) or slope (r = .14, p = .42) of sex risk behaviors. On the other hand, drug symptoms and sex risk behaviors were associated both at their intercepts (r = .55, p < .001) and slopes (r = .35, p < .01), as was the intercept of sex with the slope of drug symptoms (r = -.34, p < .01) and the drug intercept with the sex slope (r = -.26, p < .01). Individuals who reported more drug symptoms at age 21 also reported more sex risk behaviors, and these behaviors tended to change together across time. Reporting more of either at the first time point was related to greater decreases over time.

Time-specific covariation

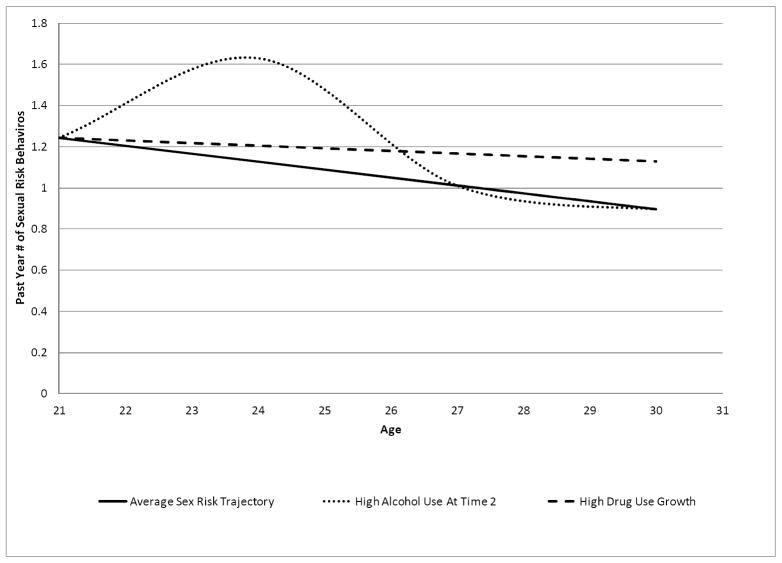

At the state level, we examined time-specific covariation between sex risk behaviors and alcohol and drug symptoms. These covariances represented how one’s level of alcohol symptoms at a given year was related to sex risk behaviors or drug symptoms over and above variation explained by each individual’s overall trajectory. In essence, these effects tested how disturbances from an individual’s average trajectory were related. We also tested whether these associations changed over time by first freely estimating all covariances across time, and comparing that model to one with all covariances fixed to be equal across time. A significant chi-square difference test would indicate that constraining parameters to be equal across time reduced model fit, which we then probed by successively freeing each parameter to identify ill fitting constraints. Results indicated that, over and above their trajectories, alcohol symptoms covaried with sex risk behaviors (Cov = .20, p < .001), and these effects were equal across all ages. These findings suggest that, for every one additional alcohol symptom that an individual reported over and above what would be expected based on their trajectory of symptoms, on average .20 more sex risk behaviors were found at that time point than would be predicted by that individual’s longitudinal trajectory. Figure 2 illustrates this effect for an individual who reported one additional symptom above and beyond that predicted by their trajectory at Time 2. On the other hand, drug symptoms were uncorrelated with sex risk behaviors at the state level (r = .01-.08, p > .25), and thus these effects were fixed to zero in the final model, with no significant decrease in model fit. Finally, alcohol symptoms were also correlated with drug symptoms from age 21 - 27 (Cov = .42, p < .001), but not at age 30 (Cov = .01, p = .94).

Figure 2.

Trajectories of sexual risk behaviors for the average participant, for a participant with 1 additional symptom of alcohol abuse or dependence above and beyond that predicted by their trajectory at Time 2, and for a participant with drug use growth +1 SD above the mean

Finally, because the sample was drawn from a high-risk population, and was exposed to a social development intervention in early childhood, we tested the influence of intervention status and early childhood poverty. We also tested for generalizability of the final model by testing the influence of ethnicity or gender. When added as either predictors of the latent factors or as moderators of the associations among the latent factors and the time-varying covariates, the strength of the associations or the interpretation of the current models did not change, suggesting that findings were robust across gender; Caucasian, African-American, and Asian-American individuals; SES; and involvement in the intervention.

Discussion

Our results provided differential support for trait and state associations across young adulthood, indicating that drug use disorder symptoms and risky sexual behaviors were associated at the trait, but not the state level, while alcohol symptoms were associated with risky sexual behaviors at the state, but not the trait level. These state-level effects, however, should be distinguished from more proximal situational effects, which require event-level analyses to detect. Rather, these state effects should be interpreted as time-specific effects that could be driven either by behaviors (i.e., intoxication leading to risky sexual activity) or shared contexts or social environments and norms that are time specific and make both alcohol symptoms and risky sexual activity more likely. These findings suggest that high-risk sexual behaviors during young adulthood may be driven both by trait and state factors, and intervention efforts may be successful if they are either aimed at high-risk individuals, or if they work to disaggregate alcohol use from risky sexual activities.

Some prior research has suggested that engaging in alcohol and drug use during adolescence was related to high-risk sexual activity at least in part because of common traits [13] that caused individuals to be more likely to be involved in both. However, young adulthood is a developmental period of maturation, with population-level declines in traits such as sensation seeking that link substance abuse and high-risk sexual behaviors [13, 37, 38]. Our findings demonstrated that during young adulthood, even as the general prevalence of risk behaviors declines, the same individuals will tend to exhibit both high-risk sexual activities and drug use disorder symptoms rooted in sensation seeking or some broader personality risk factor such as impulsivity. Taken together, these findings suggest that interventions that target these broad risk factors (such as sensation seeking or impulsivity) as a means of reducing either sex risk behavior or problematic drug use among adults will, as with adolescents, provide spillover benefits in the form of reduction of other risk behaviors. On the other hand, interventions aimed at specific health behaviors, such as limiting drug use behaviors or increasing safe sexual practices may not translate across risk behaviors. Future research is needed to understand which personality traits (such as impulsivity or sensation seeking) account for this covariation.

Although research during adolescence suggested a link between trajectories of alcohol use disorder symptoms and sex risk [29], our findings demonstrated that during young adulthood only the levels of alcohol use disorder symptoms and risky sexual behaviors were correlated, but not their general pattern of change across young adulthood. This trait-level de-linking of alcohol symptoms and sex risk behaviors in young adulthood may be explained (at least in part) by the high prevalence of alcohol use disorder symptoms during young adulthood. Although alcohol use disorder symptoms are non-normative during adolescence [39], as many as 37% of college students meet criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence [40], while epidemiological research has estimated that nearly 20% of individuals between ages 18 and 29 meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder [41]. In other words, alcohol disorder symptoms are relatively common during young adulthood, and developmental trajectories of alcohol disorders and risky sex may not be associated during young adulthood because many young adults’ alcohol use disorder symptoms are not explained by individual differences in a propensity for problem behaviors. Instead, other contextual factors specific to this developmental period are likely to produce problematic alcohol use, but not risky sexual behaviors.

The current findings were consistent with this experimental work with alcohol, demonstrating that alcohol use disorder symptoms and risky sexual behaviors were linked not at the trajectory level, but at specific time points, independent of trajectory. When an individual reported alcohol abuse or dependence symptoms that were higher than would be predicted by their individual trajectory of alcohol symptoms, there were concurrent deviations in sex risk behaviors. Moreover, this association was equal across all ages, suggesting that regardless of the overall declines in both risk behaviors in the population, alcohol symptoms and risky sexual behaviors were linked above and beyond their developmental trajectories. These findings suggest that, although targeting high-risk individuals may be one effective route to reduce high-risk sexual behaviors, more specific interventions targeted at weakening the link between alcohol use and risky sexual practices are also needed. For example, interventions could seek to reduce environmental or social variables that enhance the association between high-risk sexual activity and alcohol use.

Strengths of the current study include its large community sample, prospective design, and the utilization of latent growth curve models to tease out state and trait associations. However, the study has limitations that should be noted. First, our measure of risky sexual behaviors largely captures variation in non-use of condoms and casual sex with multiple sexual partners; other measures of risky sexual behaviors may be differentially influenced by substance use disorder symptoms. Moreover, the majority of participants who reported drug abuse or dependence symptoms were involved with marijuana. Samples with higher levels of involvement in harder drugs, such as cocaine or amphetamines, may be more sensitive to detecting state-specific associations between drug involvement and risky sexual activities. Finally, our “state” associations capture time-specific covariation of behaviors within a given year, but do not capture the actual effects of alcohol intoxication on sex risk behaviors. It may be these effects result from shared time-specific social or contextual factors that produce elevations in alcohol use disorder symptoms and sex risk behaviors, rather than the direct effects of alcohol on sex. Future research, using methodology such as event-level analysis or ecological momentary assessment methods, should attempt to disentangle the short-term associations between alcohol use disorder symptoms and sex risk behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants #1R01DA09679-11, #9R01DA021426-08, and #R001DA08093-12 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and #21548 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these funders.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented in June 2011 at the 34th Annual Research Society on Alcoholism Scientific Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Klein DJ. Long-term effects of drug prevention on risky sexual behavior among young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev Perspect. 2007;1:68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: what changes, and why? Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1021:51–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [April, 19, 2011]. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/surv2008-complete.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH report: Sexually transmitted diseases and substance use. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45:921–33. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Martineau AM. Alcohol myopia and condom use: Can alcohol intoxication be associated with more prudent behavior? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:605–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George WH, Davis KC, Norris J, Heiman JR, Stoner SA, Schacht RL, et al. Indirect effects of acute alcohol intoxication on sexual risk-taking: The roles of subjective and physiological sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38:498–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebel-Lam AP, MacDonald TK, Zanna MP, Fong GT. An experimental investigation of the interactive effects of alcohol and sexual arousal on intentions to have unprotected sex. Basic App Soc Psychol. 2009;31:226–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang AR. The social psychology of drinking and human sexuality. J Drug Issues. 1985;15:273–89. [Google Scholar]

- 12.George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:92–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper ML, Orcutt HK. Alcohol use, condom use and partner type among heterosexual adolescents and young adults. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:413–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bollen K, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussong AM, Chassin L. Stress and coping among children of alcoholic parents through the young adult transition. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:985–1006. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King KM, Molina BS, Chassin L. Prospective relations between growth in drinking and familial stressors across adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:610–22. doi: 10.1037/a0016315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J, Witkiewitz K, McMahon RJ, Dodge KA. Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. A parallel process growth mixture model of conduct problems and substance use with risky sexual behavior. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Effects of social development intervention in childhood fifteen years later. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:1133–41. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins JD, Smith BH, Hill KG, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Promoting social development and preventing health and behavior problems during the elementary grades: Results from the Seattle Social Development Project. Victims Offenders. 2007;2:161–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Version III (May 1981) Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: Long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Partridge F, Silva PA, Kelly J. DSM-III disorders in a large sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:611–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Fombonne E, Poulton R, Martin J. Differences in early childhood risk factors for juvenile-onset and adult-onset depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:215–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leaf PJ, Myers JK, McEvoy LT. Procedures used in the Epidemiological Catchment Area study. In: Robins LN, Reiger DA, editors. Psychiatric disorders in America. New York: Free Press; 1991. pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Magdol L, Silva PA, Stanton WR. Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: Prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance, and new case incidence from ages 11 to 21. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:552–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Carmola Hauf AM, Wasserman MS, Paradis AD. General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders by early adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:223–31. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo J, Chung I-J, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:354–62. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mplus 5.1 [computer program]. Version. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans RDH, Pollock DSG, Satorra A, editors. Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker. London: Kluwer Academic; 2000. pp. 233–47. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monahan KC, Hawkins JD. Covariance of problem behaviors in adolescence. Unpublished manuscript. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):101–17. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalichman SC, Cain D. A prospective study of sensation seeking and alcohol use as predictors of sexual risk behaviors among men and women receiving sexually transmitted infection clinic services. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:367–73. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, George WH, Norris J. Alcohol use, expectancies, and sexual sensation seeking as correlates of HIV risk behavior in heterosexual young adults. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:365–72. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings 2008. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. NIH Publication No. 09-7401. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:263–70. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering R. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]