Abstract

Background

Pre-transplant nephrectomy is performed to reduce risks to graft and recipient. The aims of this study were to evaluate (1) indications, surgical approach, and morbidity of native nephrectomy and (2) the effects of kidney removal on clinical and biological parameters.

Methods

This study was designed as a single-center retrospective cohort study in which 49 consecutive patients with uni- or bilateral native nephrectomies were identified from a total of 126 consecutive graft recipients in our pediatric kidney transplantation database between 1992 and 2011. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory details were extracted from charts and electronic records, including operation reports and pre- and post-operative clinic notes.

Results

Of the 49 nephrectomized patients, 47% had anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract, 22% had cystinosis, 12% had focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and 6% had congenital nephrotic syndrome. Nephrectomy decisions were based on clinical judgment, taking physiological and psychosocial aspects into consideration. Nephrectomy was performed in patients with polyuria (>2.5 ml/kg/h) and/or large proteinuria (>40 mg/m2/h), recurrent urinary tract infection or (rarely) hypertension. Urine output decreased from (median) 3.79 to 2.32 ml/kg/h (−34%), and proteinuria from 157 to 100 mg/m2/h (−40%) after unilateral nephrectomy (p = 0.005). After bilateral nephrectomy, serum albumin, protein and fibrinogen concentrations normalized in 93, 73, and 55% of nephrectomized patients, respectively. Clinically relevant procedure-related complications (peritoneal laceration, hematoma) occurred in five patients.

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrate quantitatively that native nephrectomy prior to transplantation improved serum protein levels and anticipated post-transplant fluid intake needs in select children, reducing the risk of graft hypoperfusion and its postulated consequences for graft outcome.

Keywords: CAKUT, Cystinosis, Nephrotic syndrome, Peritoneal dialysis, Polyuria, Proteinuria, Retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy

Introduction

Indications for native nephrectomy in patients with endstage renal disease (ESRD) prior to kidney transplantation (KT) are not well defined. Malfunctioning kidneys are removed if they are perceived to convey short- or long-term risks to the KT recipient or the graft. The spectrum of renal and urinary tract disorders leading to ESRD differs between adults and children. In addition, the removal of the native kidney(s) in young children and infants prior to transplantation entails specific clinical challenges related to fluid management and nutrition. Hence, indications for pre-transplant nephrectomy are expected to vary between the adult and pediatric patient groups. Studies on the biological effects of nephrectomy are limited, and outcome data are needed for informed decision-making.

The removal of endstage kidneys has been advocated for patients with large proteinuria, refractory hypertension, recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI) or urosepsis, urolithiasis, and polyuria [1, 2]. Heavy proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia are associated with an increased risk of thrombosis and thromboembolic events [3–5]. Disturbed hemostasis in nephrotic syndrome is thought to be caused by the loss of select coagulation factors in the urine, by unregulated protein and lipid production and by endothelial injury [3, 6–8]. Removing the native kidney(s) in nephrotic patients is expected to reduce the risk of acute graft thrombosis, intravascular volume depletion, nutritional deficit, and delayed wound healing [9].

There is minimal quantitative data on the effect of residual native kidney urine output and post-KT graft function in children [10, 11], and the few publications available on adults report conflicting results [12, 13]. Case reports [14] and anecdotal experience suggest that pediatric patients with polyuria due to tubular disorders or renal dysplasia may continue to have substantial native urine output for prolonged periods after transplantation. Large native urine output post-transplant can lead to extracellular volume depletion and hypoperfusion of the graft and may exacerbate the perfusion mismatch between small recipients and adult donors. Chronic graft hypoperfusion may be associated with an important—according to some studies, irreversible—drop in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and accelerated fibrosis, particularly in the smallest renal transplant recipients [10, 15–19]. Volume depletion and renal hypoperfusion can exacerbate drug (e.g. cyclosporine) nephrotoxicity [20, 21] and further imperil the perfusion of adult-size grafts in young recipients. These considerations provide the rationale to optimize the conditions for post-transplant fluid management, including the removal of one or both kidneys.

In the absence of prospective data or evidence-based guidelines, we reviewed our pediatric experience of pre-transplant nephrectomies. The aims of this study were (1) to examine indications, surgical approach, and complications of native nephrectomies prior to transplantation and (2) to determine the effects of uni- and bilateral nephrectomy on selected biological and clinical parameters, specifically urine volume and protein loss (where applicable) and serum protein concentrations.

Material and methods

Study design

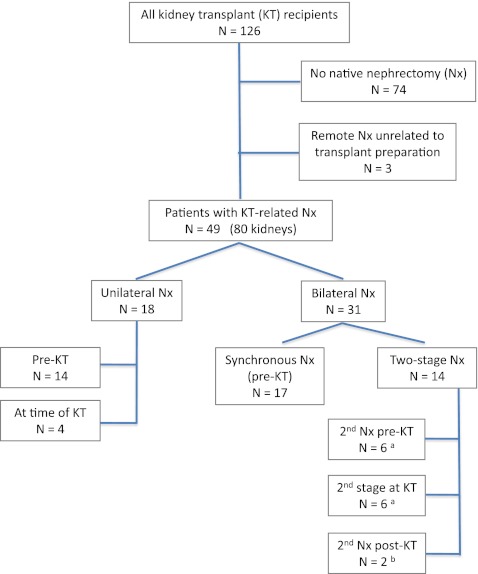

The study was designed as a single-center retrospective cohort study. We identified consecutive patients with uni- or bilateral native nephrectomies from a total of 126 consecutive graft recipients in our pediatric KT database. For reasons of data availability, we limited our review to patients who received a graft between December 1992 and October 2011 (18.9 years) (Fig. 1). The study was conducted in accordance with institutional ethics regulations; since it was a retrospective chart analysis, no informed consent was required. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory details, including serum creatinine, albumin, total protein and fibrinogen concentrations, UTIs and imaging, blood pressure, urine volume, and 24-h protein excretion pre- and post-surgery were extracted from charts and electronic records, including operation reports and pre- and post-operative clinic notes.

Fig. 1.

Summary of patients and nephrectomy procedures. aOne patient each had the first kidney removed previously for non-kidney transplant-related reasons, bnative kidneys removed 4 and 19 months post-kidney transplant (KT) because of frequent urinary tract infection

Patients and surgical procedures

We identified 49 transplant recipients with uni- or bilateral nephrectomy (80 removed kidneys). Three patients who had undergone unilateral removal of poorly functioning kidneys due to lower urinary tract abnormalities at 4.7, 5.7, and 18 years prior to KT were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1). With few exceptions [congenital nephrotic syndrome, Wilms tumor (WT), or Denys–Drash syndrome (DDS)], all patients had endstage renal disease at the time of pretransplant nephrectomy. Most patients were followed pre-operatively by the pediatric nephrology and (in part) the urology team at this institution. Ten patients have been described in a recent publication evaluating our experience with retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy (RPN) in children receiving peritoneal dialysis [22]. The decision to remove one or both kidneys, concurrently or sequentially, depended on the diagnosis and the perceived benefit, such as preservation of some urine output during dialysis, and was based on consensus among the team of nephrologists and surgeons. Clinical judgment and psychosocial considerations, including the recipient’s age-related maturity, ability or willingness to cope with large volume fluid intake post-KT and overall medical adherence figured importantly as measurable (objective) parameters. The operative approach was at the discretion of the responsible surgeon.

Clinical definitions

In the absence of a generally accepted definition, we specified polyuria for this review as a sustained urine output of >2.5 ml/kg/h. Proteinuria was defined as >4 mg urine protein/m2 per hour and large (nephrotic range) proteinuria as >40 mg/m2 per hour [23]. To assess the effect of (unilateral) kidney removal on urine output and proteinuria, we chose timed urine collection(s) closest to the procedure, generally <2 months pre- and post-nephrectomy. Measurements during the first 2 weeks post-nephrectomy were omitted from analysis to avoid confounding effects of perioperative fluid administration or dialysis adjustments. Charts were reviewed for the incidence of UTI at least 1 year prior to nephrectomy (median 2.8 years), between nephrectomy and KT, and ≥24 months after KT. Recurrent UTIs were defined as ≥2 documented infections within a 12-month period [24].

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as median and range unless noted otherwise. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, and non-parametric (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks and Mann–Whitney U) tests for continuous variables. Linear regression was used to assess longitudinal changes in urine output and biochemical results pre- and post-nephrectomy. Assumptions of a normal distribution of residuals, as well as a lack of heteroscedasticity, multicollinearity and non-linearity were satisfied (data not shown). A critical p value of 0.05 was used. The Bonferroni correction was applied in cases of multiple testing. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata v.10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Demographics, etiology of ESRD, and timing of nephrectomy

Of 126 pediatric renal transplant recipients who received a graft during the reviewed period, 49 patients (39%) underwent uni- or bilateral native nephrectomies (80 kidneys; Fig. 1). The median age at transplantation in the nephrectomized study cohort was 9.4 years (range 2.0–19.5 years). The main diagnoses leading to ESRD and nephrectomy were congenital (anatomical) anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT), nephropathic cystinosis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and congenital nephrotic syndrome (CNS) (Table 1). Histopathological reports were available for 21 CAKUT patients, with evidence of renal dysplasia in 71% of these.

Table 1.

Nephrectomy cohort: clinical and demographic parameters

| Etiology of ESRD | Number of patients (%)a | Age at Nx (years)b | Nephrectomies (Nx)c | Nx to KTb (months) | Indication for Nxd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral pre- /at KT | Bilateral synchronous/staged / at KTe | |||||

| CAKUTf | 23/49 (46.9%) | 6.0 (2.2–17.9) | 6/3 | 5/3/6g | 1.0 (0.0–25.5)h | UTI/VUR (n = 10), polyuria (8), proteinuria (1), polyuria and proteinuria (1), UTI and polyuria (1), UTI and proteinuria (1), hypertension (1) |

| Cystinosis | 11 (22.4%) | 11.1 (8.2–17.6) | 5/1 | 5/0/0 | 1.1 (0.0–4.1) | Polyuria and proteinuria (6), polyuria (4), proteinuria (1) |

| FSGS | 6 (12.2%) | 8.1 (6.3–12.7) | 2/0 | 3/1/0 | 17.4 (4.9–41.4) | Proteinuria (5), proteinuria and hypertension (1) |

| CNS | 3 (6.1%) | 4.8 (4.0–5.5) | – | 2/1/0 | 2.3 (2.3–17.6) | Proteinuria (3) |

| Denys–Drash syndrome | 2 (4.1%) | 1.5, 4.2 | – | 1/1/0 | 1.5, 6.3 | Wilms tumor risk, proteinuria (2) |

| ADPKD/TSC | 1 (2.0%) | 16.5 | – | 1/0/0 | 1.6 | Angiomyolipoma, malignancy risk (1) |

| ARPKD | 1 (2.0%) | 2.8 | – | 0/0/1 | 0.0 | Polycystic kidney (1) |

| Bartter syndrome | 1 (2.0%) | 15.6 | – | 0/1/0 | 0.39 | Polyuria (1) |

| CIN | 1 (2.0%) | 15.8 | 1/0 | – | 7.1 | Polyuria and proteinuria (1) |

ADPKD, Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; ARPKD, autosomal recessive PKD; CAKUT, congenital anomalies of kidney and urinary tract; CIN, chronic interstitial nephritis; CNS, congenital nephrotic syndrome; ESRD, endstage renal disease; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; KT, kidney transplant; Nx, nephrectomy; PUV, posterior urethral valves; TSC, tuberous sclerosis; UPJ, uretero-pelvic junction; UTI, urinary tract infections; VUR, vesico-ureteral reflux

aTotal number of nephrectomized patients, n = 49

bLast nephrectomy in cases of staged procedures

cData are presented as the number of patients

dMedical indications for procedure closest in time to the KT are given. Decision to operate was based on a combination of psychosocial and medical or laboratory factors. Number of patients for each indication are given in parenthesis. UTI/VUR (frequent UTI and/or high-grade VUR); proteinuria (large or nephrotic-range proteinuria)

eSecond of staged Nx at time of transplant

fSpecific diagnoses include: obstructive uropathy, n = 12 (7 with PUV, 4 with UPJ or lower urinary tract obstruction; 11/12 also with renal hypo/dysplasia); VUR, 8 (frequently with renal hypo-/dysplasia); cystic dysplasia, 2 (one with prune belly syndrome). 15/ 21 patients with CAKUT and available nephrectomy pathology had confirmed dysplasia

gTwo patients with post-transplant native nephrectomy included

hExcluding one patient with remote first nephrectomy and post-KT second native nephrectomy

Thirty-four patients (69%) of the cohort commenced dialysis prior to, and 11 (23%) at the time of nephrectomy. Four patients (8%) were transplanted preemptively, before initiating dialysis: two of these were unilaterally nephrectomized 1–2 weeks prior to KT and two at transplantation. Of the patients with nephrectomy prior to KT, 51% received or intended to start peritoneal dialysis (PD), the remainder hemodialysis (HD).

Native nephrectomies were performed a median of 1.9 months (range 0–41.4 months) prior to transplantation (Table 1); 53% of the children had a living related donor graft, and the remainder received a graft from a deceased donor, almost exclusively adult.

Indications for nephrectomy

Measurable parameters influencing the decision for native nephrectomy included polyuria, large proteinuria, and recurrent UTI. Of a total of 22 patients with polyuria as an indication for nephrectomy, 45% underwent unilateral nephrectomy, and the remainder underwent bilateral synchronous (18%) or staged nephrectomy (37%). The majority of patients with polyuria had CAKUT or cystinosis (45% each). The diagnoses associated with large proteinuria and nephrectomy (n = 22) were glomerular diseases (FSGS, CNS, and Denys–Drash syndrome; 50%), cystinosis (32%), CAKUT (14%), and chronic interstitial nephritis (4%). In this cohort, 82% of children with glomerular disease, 61% of those with CAKUT, and 45% with cystinosis underwent bilateral nephrectomy (Table 1).

Surgical procedures

Eighteen patients (37%) underwent unilateral nephrectomy, 12 on the left side, this allowed for removal of the right kidney at the time of KT, if needed, which is the preferred side for the future graft. Two-thirds of the patients had both kidneys removed: 17 in a single (synchronous) operation, the remaining 14 sequentially. In ten patients the nephrectomy was performed at the time of transplantation, and two patients underwent native ureteronephrectomy 4 and 19 months post-transplant, respectively, for frequent UTIs attributed to the residual native unit (Fig. 1).

Of the patients for whom we had access to detailed surgical information, 31 organs were removed by minimally invasive surgery [transperitoneal, 5 kidneys; retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy (RPN), 26 kidneys; total number of procedures, 24], and 36 by open surgery (transperitoneal, 7; extraperitoneal, 29; total number of procedures, 30). Thirty-eight percent of nephrectomies were combined with additional procedures, such as HD or PD catheter placement, cystoplasty or KT. Of the remaining patients, the median operation time was 3.0 h for unilateral and 7.2 h for synchronous bilateral procedures (p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney U test). The duration of open versus minimally invasive surgery was 3.0 versus 5.2 h (p = 0.02). After stratification for the removal of one or both kidneys, the difference between open versus minimally invasive surgery time remained statistically significant for bilateral synchronous procedures (p = 0.002), but not for unilateral ones (p = 0.39, Mann–Whitney U test). These times reflect substantial trainee involvement.

Effect of nephrectomy on urine output

The median daily urine output of 15 patients with polyuria who underwent unilateral nephrectomy (including the first of staged nephrectomies) decreased from 2.1 l (3.91 ml/kg/h) to 1.4 l (2.39 ml/kg/h; median change −40%; p < 0.005). The percentage post-operative reduction in urine output was not related to the amount of pre-operative polyuria (p = 0.73; linear regression r 2 = 0.30). Changes in urine output according to nephrectomy procedure are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effect of nephrectomy (Nx) on urine output of polyuric patientsa

| Nephrectomy | Patients (n)a | Median urine output (range)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Nx (ml/kg/h) | Post-Nx (ml/kg/h) | % Differencec | ||

| Unilateral | 9 | 3.79 (1.43– .87) | 2.22 (0.57–5.00) | −34* (−24 to −72) |

| Bilateral, first stage | 6 | 4.08 (3.11–6.03) | 2.39 (1.90–3.45) | −42* (−20 to −55) |

| Bilateral, second stage (rendered anuric) | 7 | 2.87 (1.85–6.13 ) | – | – |

| Bilateral, synchronous (rendered anuric) | 4 | 7.62 (3.81–8.98) | – | – |

*p < 0.05

–, Not applicable

CAKUT, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract

aUnilateral nephrectomy: CAKUT (n = 3 patients), cystinosis (5), chronic interstitial nephritis (1). Bilateral, staged nephrectomy: CAKUT (6), Bartter syndrome (1). Bilateral, synchronous nephrectomy: cystinosis (4). Unilateral nephrectomies at the time of KT were excluded. Some patients had additional indications leading to nephrectomy (see Material and methods)

bUrine output number reflects last documented collection prior to Nx. See Material and methods for polyuria definition. Decision to operate was based on a combination of psychosocial and medical factors

cWilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test

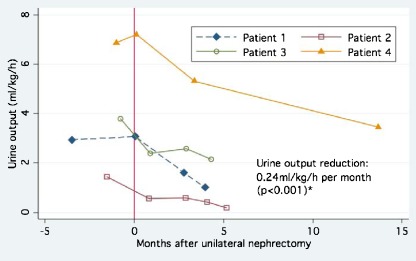

We tested the possibility that urine output of ESRD patients further declined after unilateral nephrectomy towards the time of KT. Adequate urine collections were available from four patients covering an observation period of 4.0–13.7 months. Median urine output declined by 36% (range −10 to −70%), corresponding to a decrease of 0.24 ml/kg/h per month (Fig. 2). In contrast, pre-nephrectomy urine production in these subjects had been relatively stable over 1–3 years, after initiation of dialysis (results not shown).

Fig. 2.

Gradual decrease of urine output following unilateral nephrectomy (in months; median 36%, range −10 to −70%). Depicted are all patients for whom data on serial, post-nephrectomy urine collections were available. 0 Time of nephrectomy. Subjects showed no appreciable decline of urine output following its stabilization after the initiation of dialysis 1–3 years prior to nephrectomy. Asterisk Analysis was performed with bivariate linear regression: effect of time on urine output (r 2 = 0.97)

Effect of nephrectomy on proteinuria and plasma proteins

Twenty-two patients with large proteinuria (with or without polyuria or frequent UTI) underwent nephrectomy. After unilateral nephrectomy (including the first of sequential nephrectomies), urine protein excretion decreased by a median of 35%, from 3.7 to 2.4 g per 24 h (158 to 102 mg/m2/h) (p = 0.01, Wilcoxon signed-ranks test). Total serum protein, albumin, and fibrinogen concentrations were within reference ranges in 64, 69, and 36% of patients, respectively, prior to nephrectomy and increased modestly after the removal of one kidney, accompanied by a decrease of fibrinogen concentrations. Details are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effects of nephrectomy (Nx) on patients with large proteinuriaa

| Procedure | Variable and unitsb | Number of patientsc | Pre-Nxd | Post-Nx | Improved pre-/post-Nxd | Percentage differencee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | ||||||

| Unilateral nephrectomy | Proteinuriaa [<4 mg/m2/h] | 9 | 157 (38–329) | 100 (19–213) | 0.11/0.13 | −40* (−18 to −63) |

| Serum albumin [31–48 g/l] | 9 | 34 (20–41) | 36 (29–41) | 0.78/0.88 | +6.0 (−3 to +75) | |

| Total serum protein [61–80 g/l] | 9 | 63 (47–69) | 67 (56–72) | 0.67/0.63 | +3.3 (−6 to +40) | |

| Plasma fibrinogen [1.5–4.0 g/l] | 9 | 4.39 (3.20–7.95) | 4.89 (3.02–6.57) | 0.44/0.13 | −1.3 (+28 to −49) | |

| Bilateral nephrectomy (first stage) | Proteinuria [<4 mg/m2/h] | 3 | 293 (79–305) | 233 (36–280) | 0.00/0.33 | −21 (−8 to −54) |

| Serum albumin [31–48 g/l] | 4 | 23 (10–39) | 22 (13–43) | 0.50/0.50 | +14 (−11 to +30) | |

| Total serum protein [61–80 g/l] | 2 | 50 (37, 63) | 56 (38, 74) | 0.50/0.50 | +10 (3–17) | |

| Plasma fibrinogen [1.5–4.0 g/l] | 2 | 6.47 (3.74, 9.20) | 5.45 (3.64, 7.26) | 0.50/0.50 | −12 (−3 to −21) | |

| Bilateral nephrectomy (rendered anuric)f | Proteinuria [<4 mg/m2/h] | 15 | 322 (100–659) | 0 | 0.00/– | N/A |

| Serum albumin [31–48 g/l] | 15 | 25 (10–33) | 36 (28–43) | 0.13/0.93 | +33** (3–260) | |

| Total serum protein [61–80 g/l] | 15 | 51 (34–59) | 62 (55–77) | 0.00/0.73 | +17** (7–52) | |

| Plasma fibrinogen [1.5–4.0 g/l] | 14 | 6.15 (3.97–16.35) | 3.99 (2.58–5.77) | 0.07/0.55 | −42** (−18 to −71) | |

*p < 0.05, ** < 0.005

N/A, not applicable

aLarge proteinuria is defined as the excretion of >40 mg/m2 per hour (normal <4 mg/m2/h). In some cases, nephrectomy was performed for other indications than (large) proteinuria

bVariables reflect last documented measurements and urine collections prior to and at least 2 (up to 8) weeks post-Nx (see Material and methods). Some patients also presented polyuria or other conditions leading to nephrectomy (see Table 1). Decisions were based on a combination of psychosocial and medical factors, and previous laboratory data (preceding immediate pre-operative measurements). Reference ranges are given in square brackets

cNumber of patients with available measurements for each biomarker

dFraction of patients with urine protein excretion below the nephrotic threshold of 40 mg/m2/h, and with serum protein measurements within reference ranges, respectively, pre- and post-Nx

eWilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Results are presented as the median, with the range in parenthesis

fBilateral synchronous (n = 12) and staged bilateral nephrectomies (pre 1st/post 2nd stage measurements; n = 3)

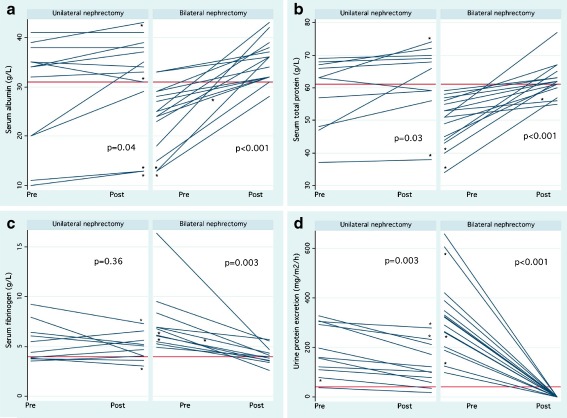

Patients scheduled for bilateral nephrectomy demonstrated greater pre-nephrectomy urine protein excretion than patients undergoing unilateral nephrectomy. Two of these patients also had polyuria. Unilaterally and bilaterally nephrectomized patients also differed with respect to their pre-operative serum albumin and protein levels (Fig. 3a, b). Within 2 months post surgery, initially low albumin and total serum protein concentrations in patients undergoing bilateral nephrectomy increased by 33 and 17%, respectively, while previously elevated fibrinogen concentrations decreased by 42% to almost normal levels (all p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Serum albumin (a), total protein (b), and fibrinogen (c) concentrations, and urine protein excretion (d) pre- and post-unilateral and bilateral nephrectomy. Horizontal Lower reference ranges for serum tgroupalbumin and total protein (31 and 61 g/l, respectively), upper range for fibrinogen (4.0 g/L), and definition of nephrotic range proteinuria (40 mg/m2/h). Analyses were performed with Wilcoxon signed-rank test. In cases of sequential nephrectomies, an asterisk indicates measurements before/after the first (unilateral) and before/after the second procedure (bilateral nephrectomy). Note that the majority of patients undergoing unilateral nephrectomy had large proteinuria, but also polyuria or other risk factors leading to kidney removal

Normal serum albumin, protein, and fibrinogen concentrations were recorded in 93, 73, and 55%, respectively, of bilaterally nephrectomized children with prior nephrotic range proteinuria, measured within 2 weeks to 2 months post-nephrectomy.

Recurrent UTIs

To ascertain whether native nephrectomy led to the intended reduction of UTI rates, we analyzed nine patients who had undergone nephrectomy for recurrent UTI and for whom data were available (3 unilateral and 6 bilateral nephrectomies). Three of the patients were nephrectomized at or after KT, and for one of these patients there was insufficient post-operative information. Four of the five remaining patients had no more UTIs between nephrectomy and KT, and one had a single infection (observation period 1.1 years, range 0.1–2 years). Post-KT, three of the nine patients remained free of UTIs during 2 years of observation (range 0.3–4.8 years), and six patients had at least one recurrence of UTI (median 3.0 UTIs per person-year, range 0.2–24.4 UTIs). All six patients had persistent UTI risks, such as VACTERL sequence, posterior urethral valve bladder, cystoplasty, and intermittent catheterizations, not all of which are amenable to surgical correction. However, two of the latter patients underwent successful post-KT native nephrectomy, reducing the infection rate from 8.8 and 4.0 per year, respectively, to <0.34 per year.

Hypertension

Persistent arterial hypertension (in addition to large proteinuria) was the indication for bilateral nephrectomy in a patient with FSGS. A second patient with dysplastic kidneys underwent bilateral renal embolization for hypertension and subsequently bilateral nephrectomy prior to his referral to our center. Post-nephrectomy blood pressure control improved in both patients and resulted in the reduction of the number of antihypertensive drugs from four to two and from two to zero, respectively.

Nephrectomy-related complications

Clinically important, procedure-related complications were noted in five patients undergoing nephrectomy prior to KT for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD; n = 1 patient), DDS/WT (2), and cystinosis with polyuria or polyuria and large proteinuria (2). Peritoneal tears occurred in 4/20 “at-risk” patients, i.e., children receiving or planning to initiate PD, including 3/10 patients undergoing open retroperitoneal nephrectomy [n = 13 surgeries (removal of 14 kidneys); one associated with a large polycystic kidney and repair of bilateral hydroceles] and 1/10 patients undergoing bilateral synchronous RPN (11 surgeries, 14 kidneys). All four patients required temporary HD. The fifth patient experienced a retroperitoneal hematoma following open, extraperitoneal nephrectomy, which required transfusions of packed red blood cells and fresh plasma.

Minor complications related to the anesthesia or surgical technique were partial lung atelectasis (n = 3) and retroperitoneoscopy-associated (expected) transient subcutaneous emphysema (n = 2). Loss of urine output due to bilateral nephrectomy resulted in fluid overload and/or volume-mediated hypertension in five patients with ARPKD (n = 1) and FSGS (n = 4). They were managed medically by intensified dialysis.

Discussion

Indications for peritransplant nephrectomy are controversial, and clinical practice varies according to perceived risks and benefits. The purpose of this study was to review our pediatric experience and to evaluate the biological effects of uni- and bilateral nephrectomy, specifically on urine output and proteinuria, where applicable, and serum proteins. We commonly base nephrectomy decisions on physiological, clinical and psychosocial determinants, with the goal to optimize the conditions for favorable graft outcome. Physiological risk factors are those compromising volume status and the perfusion of the (adult) graft in the pediatric recipient [10, 16, 19]. Clinical arguments include risks for graft and recipient due to UTI/urosepsis or persistent, severe arterial hypertension. Important psychosocial factors are the predicted inability or stated unwillingness to comply with increased post-transplant fluid intake, particularly among children and teenagers.

Our report represents the largest pediatric cohort examining clinical and biological effects of pre-transplant nephrectomies. Most prior publications have described indications and surgical outcomes in adult patients [25–30]. In addition to technical reports, we identified only two case series mentioning the inclusion of children: In the first study of 36 patients aged 10–67 years [28], eight nephrectomized patients were compared with 28 patients after ureteral reimplantation or no surgery prior to KT. The authors found no difference in the rate of UTIs between nephrectomized and non-nephrectomized recipients, but the numbers were small and children were not analyzed separately [28]. The second study [29] comprised 62 patients, including 11 children (14 nephrectomies). Pediatric indications were UTI (n = 9) or large proteinuria (n = 2), compared with hypertension, UTI, lithiasis, renal carcinoma, and polycystic kidney disease in the adult patients [29].

In our study, we did not intend to evaluate whether nephrectomy improves transplant outcome or graft and patient survival. The novelty of this report is that it describes the effects of native nephrectomy on urine volume, proteinuria, and serum proteins. Indeed, there are no data in the literature to quantify these biological effects. Our findings may help inform future decision-making. The renal diagnoses of the nephrectomized cohort are similar to those of contemporary, non-nephrectomized graft recipients transplanted in our center, with the exception of nephrotic syndrome patients. This further suggests that nephrectomy decisions were individualized, i.e. based on psychosocial factors and clinical judgment, and not (just) on the 24-h urine collection.

The decision to render young ESRD patients with preserved urine output anuric is not trivial. Where possible, the second (staged) nephrectomy was delayed to the time of KT to allow the advantage of residual urine production [31, 32] and to avoid additional surgeries and anesthesia. Removing the second kidney at the time of KT may circumvent this problem, but prolongs transplant surgery. It has been argued that patients may benefit from residual urine output and metabolic renal activity should they return to dialysis in case of early graft failure [33]. However, we did not encounter this scenario in our cohort.

Patients undergoing nephrectomy risk peritoneal laceration in addition to potential surgery and anesthesia complications. In our cohort, clinically important, procedure-related adverse events were documented in five patients, mainly peritoneal leaks that required temporary HD instead of the planned initiation or continuation of PD. Few patients experienced fluid overload and hypertension post-operatively, which is an expected outcome in patients rendered anuric. Interestingly, most of the latter patients had been nephrectomized for FSGS and persistent nephrotic syndrome. All responded well to medical management.

Compared to conventional, open nephrectomy, minimally invasive surgery shortened recovery and hospitalization times. Transperitoneal (open or laparoscopic) techniques would require switching from PD to (at least temporary) HD post-nephrectomy. The retroperitoneoscopic approach [34] preserved peritoneal integrity in 11 of 12 procedures. Three of ten patients undergoing open retroperitoneal nephrectomies suffered peritoneal laceration, but these procedures were all performed during the first half of the review period.

Our rationale for nephrectomy in children with polyuria was twofold: to reduce the risk of graft injury due to hypoperfusion and to alleviate the difficulty of maintaining high post-KT fluid intake. Hypoperfusion of the graft may have acute (tubular necrosis, graft thrombosis) and long-term consequences (accelerated chronic graft fibrosis) [9, 16, 19, 35].

Studying hemodynamic changes induced by the transplantation of adult-sized kidneys into young recipients, Salvatierra and his group reported that the blood flow in the transplanted renal artery diminished by one-half compared to the original measurements in the living donor and concluded that aggressive intravascular volume replacement is necessary to achieve and maintain optimal aortic (and renal arterial) blood flow following renal transplantation [16]. Berg et al. and others have shown that children receiving kidneys from pediatric donors revealed increasing absolute and stable relative GFR compared with those receiving adult kidneys [10, 18, 36]. By careful histological comparison of protocol biopsies, Naesen et al. [19] found functionally relevant, progressive non-immune graft injury in pediatric recipients soon after the transplant of adult-size kidneys. They postulated that graft ischemia associated with donor-recipient size discrepancy is a major risk factor for chronic tubulo-interstitial damage. The same group provided molecular evidence, employing cDNA microarray techniques, that early graft hypoperfusion induces the coordinated expression of profibrotic genes in the graft. Interestingly, gene activation was evident before any histological appearance of fibrosis [37]. These findings are relevant to our subjects who received almost exclusively adult donor kidneys.

Large proteinuria is believed to increase the risk of graft and extrarenal venous thrombosis due to the imbalance of pro- and antithrombotic factors [3, 5, 38], compounded by transplant-associated endothelial injury [39–41]. There is little doubt that persistent, severe nephrotic syndrome poses short- and long-term risks for the transplant recipient [40]. We have demonstrated that patients with compensated large proteinuria, but only mildly decreased serum albumin concentrations, experienced a modest rise of serum proteins after unilateral nephrectomy. Bilateral nephrectomy, on the other hand, fully corrected albumin, total protein and fibrinogen concentrations in the majority of previously hypoalbuminemic patients (see Fig. 3 and Results section).

It is of note that not all patients with recurrent UTI benefitted from pre-KT nephrectomy. This was likely due to variability in the underlying anatomical/developmental abnormalities affecting the lower urinary tract and bladder.

Conclusion

The indication for pre-transplant native nephrectomy in our cohort was based on a combination of physiological, clinical, and psychosocial considerations. Unilateral nephrectomy reduced polyuria in all patients, by a median of 34%, and proteinuria by 40%, while bilateral (synchronous or staged) nephrectomy improved serum total protein, albumin and fibrinogen concentrations significantly by 17–42%. The main risk of the procedure is peritoneal laceration with temporary interruption of peritoneal dialysis. Proof that nephrectomy ameliorates graft fibrosis and long-term outcome in select patients would require a prospective, randomized, and controlled trial.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all nephrologists, urologists, transplant surgeons, and nursing staff for the care of the patients reported in this study. Particular thanks go to Angela Burns, Debbie Harmidy, and Sonia Champoux for their ready help localizing missing information.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Footnotes

Fatemeh Ghane Sharbaf and Martin Bitzan contributed equally to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cochat P. Is there a need for a multicenter study to determine the optimal approach to recurrent nephrotic syndrome following renal transplantation? Pediatr Transplant. 2001;5:394–397. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2001.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochat P, Offner G. ESPN IV.11—Paediatrics (specific problems) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:55–58. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_4.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau SO, Tkachuck JY, Hasegawa DK, Edson JR. Plasminogen and antithrombin III deficiencies in the childhood nephrotic syndrome associated with plasminogenuria and antithrombinuria. J Pediatr. 1980;96:390–392. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(80)80678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerlin BA, Blatt NB, Fuh B, Zhao S, Lehman A, Blanchong C, Mahan JD, Smoyer WE. Epidemiology and risk factors for thromboembolic complications of childhood nephrotic syndrome: a Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium (MWPNC) study. J Pediatr. 2009;155:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, Levin A, Hladunewich MA, Nachman PH, Hogan SL, Cattran DC, Reich HN (2012) Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 81(2):190–195 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Singhal R, Brimble KS. Thromboembolic complications in the nephrotic syndrome: pathophysiology and clinical management. Thromb Res. 2006;118:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tkaczyk M, Czupryniak A, Owczarek D, Lukamowicz J, Nowicki M. Markers of endothelial dysfunction in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:197–202. doi: 10.1159/000110088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bramham K, Hunt BJ, Goldsmith D. Thrombophilia of nephrotic syndrome in adults. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009;7:368–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harmon WE, Stablein D, Alexander SR, Tejani A. Graft thrombosis in pediatric renal transplant recipients. A report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative study. Transplantation. 1991;51:406–412. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199102000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohlin AB, Berg U. Renal functional adaptation of the adult kidney following transplantation to the child. Kidney Int. 1991;39:129–134. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Lieburg AF, de Jong MC, Hoitsma AJ, Buskens FG, Schroder CH, Monnens LA. Renal transplant thrombosis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:615–619. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Cunha PT, Parasuraman R, Venkat KK. Rapid resolution of proteinuria of native kidney origin following live donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:351–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosconi G, Panicali L, Persici E, Conte D, Cappuccilli ML, Cuna V, Capelli I, Todeschini P, D'Arcangelo GL, Stefoni S. Native kidney function after renal transplantation combined with other solid organs in preemptive patients. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:1017–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.03.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kravarusic D, Sigalet DL, Hamiwka LA, Midgley JP, Wade AW, Grisaru S. Persistent post-transplant polyuria managed by bilateral native-kidney laparoscopic nephrectomy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:880–882. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvatierra O, Jr, Alexander SR, Krensky AM. Pediatric transplant grand rounds. Pediatric kidney transplantation at Stanford. Pediatr Transplant. 1998;2:165–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salvatierra O, Jr, Singh T, Shifrin R, Conley S, Alexander S, Tanney D, Lemley K, Sarwal M, Mackie F, Alfrey E, Orlandi P, Zarins C, Herfkens R. Successful transplantation of adult-sized kidneys into infants requires maintenance of high aortic blood flow. Transplantation. 1998;66:819–823. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvatierra O, Jr, Singh T, Shifrin R, Conley S, Alexander S, Tanney D, Lemley K, Sarwal M, Mackie F, Alfrey E, Orlandi P, Zarins C, Herfkens R. Transplantation of adult-sized kidneys into infants induces major blood flow changes. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:236–237. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(98)01517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubourg L, Cochat P, Hadj-Aissa A, Tyden G, Berg UB. Better long-term functional adaptation to the child's size with pediatric compared to adult kidney donors. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1454–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naesens M, Kambham N, Concepcion W, Salvatierra O, Jr, Sarwal M. The evolution of nonimmune histological injury and its clinical relevance in adult-sized kidney grafts in pediatric recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2504–2514. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen CW, Jordan ML, Schneck FX, Shapiro R, Tzakis A, Hakala TR, Starzl TE. Pediatric renal transplantation under FK 506 immunosuppression. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:3075–3077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nankivell BJ, Chapman JR, Bonovas G, Gruenewald SM. Oral cyclosporine but not tacrolimus reduces renal transplant blood flow. Transplantation. 2004;77:1457–1459. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000121196.71904.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szymanski KM, Bitzan M, Capolicchio J-P. Is retroperitoneoscopy the gold standard for endoscopic nephrectomy in children on peritoneal dialysis? J Urol. 2010;184(4 Suppl):1631–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niaudet P, Boyer O. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children: clinical aspects. In: Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, Yoshikawa N, editors. Pediatric nephrology. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. pp. 667–702. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai B, Liu Y, Jia J, Mei C. Long-term antibiotics for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:499–508. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.173112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg JC, Azcarate J, Fleischmann LE, McDonald FD, Menendez M, Pierce JM, Jr, Whang CW. Indications for pretransplant nephrectomy. Arch Surg. 1973;107:233–241. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1973.01350200097022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yarimizu SN, Susan LP, Straffon RA, Stewart BH, Magnusson MO, Nakamoto SS. Mortality and morbidity in pretransplant bilateral nephrectomy: analysis of 305 cases. Urology. 1978;12:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(78)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darby CR, Cranston D, Raine AE, Morris PJ. Bilateral nephrectomy before transplantation: indications, surgical approach, morbidity and mortality. Br J Surg. 1991;+78:305–307. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erturk E, Burzon DT, Orloff M, Rabinowitz R. Outcome of patients with vesicoureteral reflux after renal transplantation: the effect of pretransplantation surgery on posttransplant urinary tract infections. Urology. 1998;51:27–30. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nahas WC, Mazzucchi E, Pinheiro MS, Antonopoulos I, David-Neto E, Ianhez LE, Arap S. Role of native nephrectomy in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:717–719. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(02)02629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoma AM, Eraky I, El-Kappany HA. Pretransplant native nephrectomy in patients with end-stage renal failure: assessment of the role of laparoscopy. Urology. 2003;61:915–920. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02556-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao CT, Chen YM, Shiao CC, Hu FC, Huang JW, Kao TW, Chuang HF, Hung KY, Wu KD, Tsai TJ. Rate of decline of residual renal function is associated with all-cause mortality and technique failure in patients on long-term peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2909–2914. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafi T, Jaar BG, Plantinga LC, Fink NE, Sadler JH, Parekh RS, Powe NR, Coresh J. Association of residual urine output with mortality, quality of life, and inflammation in incident hemodialysis patients: the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-Stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:348–358. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Descoeudres B, Giannini O, Aschwanden M, Eugster T, Hopfer H, Mihatsch MJ, Steiger J, Mayr M. Silent recovery of native kidney function after transplantation in a patient with membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1345–1349. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capolicchio JP, Jednak R, Anidjar M, Pippi-Salle JL. A modified access technique for retroperitoneoscopic renal surgery in children. J Urol. 2003;170:204–206. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067293.86564.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh A, Stablein D, Tejani A. Risk factors for vascular thrombosis in pediatric renal transplantation: a special report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative study. Transplantation. 1997;63:1263–1267. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199705150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pape L, Hoppe J, Becker T, Ehrich JH, Neipp M, Ahlenstiel T, Offner G. Superior long-term graft function and better growth of grafts in children receiving kidneys from paediatric compared with adult donors. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2596–2600. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naesens M, Khatri P, Li L, Sigdel TK, Vitalone MJ, Chen R, Butte AJ, Salvatierra O, Sarwal MM (2011) Progressive histological damage in renal allografts is associated with expression of innate and adaptive immunity genes. Kidney Int. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Bilginer Y, Ozaltin F, Duzova A, Erdogan I, Aki TF, Demircin M, Bakkaloglu M, Bakkaloglu A. Right atrial thrombosis complicating renal transplantation in a child. Pediatr Transplant. 2008;12:251–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farkas JC, Tabet G, Marzelle J, Cormier F, Laurian C, Cormier JM. Arterial thrombosis: a rare complication of the nephrotic syndrome. Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;1:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim MS, Stablein D, Harmon WE. Renal transplantation in children with congenital nephrotic syndrome: a report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS) Pediatr Transplant. 1998;2:305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salvatierra O, Jr, Millan M, Concepcion W. Pediataric renal tranasplantation with considerations for successful outcomes. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:208–217. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]