Abstract

Brain tumors, including the majority gliomas, are the leading cause of cancer-related death in children. World Health Organization has divided pediatric brain tumors into different grades and, based upon cDNA microarray data identifying gene expression profiles (GEPs), it has become evident in the last decade that the various grades involve different types of genetic alterations. However, it is not known whether ion channel and transporter genes, intimately involved in brain functioning, are associated with such GEPs. We determined the GEPs in an available cohort of 10 pediatric brain tumors initially by comparing the data obtained from four primary tumor samples and corresponding short-term cultures. The correspondence between the two types of samples was statistically significant. We then performed bioinformatic analyses on those samples (a total of nine) which corresponded to tumors of glial origin, either tissues or cell cultures, depending on the best “RNA integrity number.” We used R software to evaluate the genes which were differentially expressed (DE) in gliomas compared with normal brain. Applying a p-value below 0.01 and fold change ≥4, led to identification of 2284 DE genes. Through a Functional Annotation Analysis (FAA) using the NIH-DAVID software, the DE genes turned out to be associated mainly with: immune/inflammatory response, cell proliferation and survival, cell adhesion and motility, neuronal phenotype, and ion transport. We have shown that GEPs of pediatric brain tumors can be studied using either primary tumor samples or short-term cultures with similar results. From FAA, we concluded that, among DE genes, pediatric gliomas show a strong deregulation of genes related to ion channels and transporters.

Keywords: pediatric gliomas, gene expression profiling, short term culture, ion channels and transporters, biological processes

Introduction

Brain tumors are the most common solid malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in children (Pollack et al., 2006; Dubuc et al., 2010). Among these cancers, gliomas represent the vast majority, ranging from 56 to 70%, depending on the registry and the histological criteria used (Qaddoumi et al., 2009). The most common pediatric gliomas are astrocytomas and ependymomas. They are classified as low grade gliomas (LGGs) and high grade gliomas (HGGs; Qaddoumi et al., 2009). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), low grade astrocytomas and ependymomas include pilocytic astrocytomas (PAs) WHO grade I, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs) WHO grade I, pleomorphic xantoastrocytomas (PXAs) WHO grade II, fibrillary astrocytomas (FAs) WHO grade II, ependymomas WHO grade II, subependymomas WHO grade I, and myxopapillary ependymomas WHO grade I (Louis et al., 2007). On the other hand, the high grade astrocytoma and ependymoma group is represented mainly by anaplastic astrocytomas (AAs; WHO grade III), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; WHO grade IV), and anaplastic ependymomas WHO grade III. In the group of low grade ependymomas, we also included the newly identified angiocentric glioma (AG), which is currently interpreted as predominantly juvenile WHO grade I ependymoma. GBM and AA are more frequent in adults (Qiu et al., 2008) and represent only 7% of all pediatric brain tumors (Rickert et al., 2001). Despite aggressive surgical resection and radiotherapy accompanied or followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, pHGGs prognosis remains poor (Massimino et al., 2010).

Gene mutations, copy number aberrations, structural rearrangements, or deregulation of the transcriptome have been shown to contribute to the development of brain tumors and currently play an integral role in their classification (Mischel et al., 2004; Dubuc et al., 2010). Moreover, the definition of molecular pathways differently expressed in brain tumors can help in identifying putative therapeutic targets (Bredel et al., 2005; Faury et al., 2007; Dubuc et al., 2010). Toward this aim, numerous recent studies, mainly on adults, have employed highly sensitive molecular techniques, such as comparative genomic hybridization (Koschny et al., 2002; Wiltshire et al., 2004) and cDNA microarrays (de Bont et al., 2008; Dubuc et al., 2010). In particular, cDNA microarrays are enabling evaluation of genome-wide gene expression profiles (GEPs) of brain tumors. It has been shown that significant molecular heterogeneity exists within morphologically defined cancers (Rorive et al., 2006) and that the determination of GEPs in gliomas strongly affects prediction of survival (Freije et al., 2004). Nevertheless, clinically relevant molecular signatures have been identified among brain tumors. From these studies, it has emerged that LGGs are characterized by an “antimigratory gene profile,” which is progressively lost in HGGs (Rorive et al., 2006). The latter appear to be characterized more by deregulation of genetic pathways belonging to DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, cell division, cell proliferation, and survival (Vital et al., 2010). Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric HGGs revealed key differences with adult HGGs (Paugh et al., 2010). Such molecular differences can in turn affect prognosis (Faury et al., 2007).

Ion channels and transporters are increasingly considered to bear pathophysiological relevance in tumor biology (Arcangeli et al., 2009; Arcangeli and Yuan, 2011). Although these proteins are inherent to brain (neuronal and glial) functioning and have been shown to be dysregulated in brains tumors (Preussat et al., 2003; Sontheimer, 2008; Cuddapah and Sontheimer, 2011; Arvind et al., 2012), only a few studies have specifically studied the genes encoding ion channels and transporters and their relevance in pediatric gliomas. Such small number of studies is due to the low incidence of the disease and the rarity of tissues appropriate for molecular characterization (Rorive et al., 2006; Paugh et al., 2010; Vital et al., 2010). Besides affecting the neoplastic progression, the ion channel and transporter complement of glioma cells affects how these cells alter the composition of the peritumor space, particularly the pH, [K+], and neurotransmitter levels. These factors likely contribute to cause tumor-related epileptic seizures, a very serious morbidity factor in brain cancer with a poorly understood pathophysiology (Shamji et al., 2009).

On the whole the importance of obtaining a full picture of the membrane transporter expression in brain cancer is clear.

In this study, we analyzed GEPs of a cohort of pediatric glioma (mainly LGG) samples. Due to the limited quantity and heterogeneity of the biological material available, we first confirmed that short-term culturing of the glioma samples would not alter their GEPs, while allowing to obtain higher amounts and better quality of RNA. Subsequent evaluation of differentially expressed (DE) genes was based on Functional Annotation Analysis (FAA).

Materials and Methods

Tissue collection

Surgical specimens were obtained from the Neurosurgery Unit, Meyer Children’s University Hospital, Firenze, Italy. Informed consent for the data collection was obtained from the parents, or the legal guardians. The study overall was approved by the local international review board of the Hospital. From each fresh surgical specimen a macroscopically representative fragment was selected, that was further cut into two corresponding pieces. One was further processed for histological analysis and diagnosis. An expert pathologist, AMB, determined the histological diagnosis using standard criteria (Buccoliero et al., 2002). The other piece was further subdivided under sterile conditions. The two pieces were immersed either in RNAlater™ solution (Ambion by Life Technologies, USA), for RNA extraction or in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), until minced for obtaining the primary culture. The cohort comprised five PAs (WHO grade 1), one AG (WHO grade 1), one ependymoma (E; WHO grade 2), one anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AO; WHO grade 3), one atypical meningioma (AM; WHO grade 2), and 1 GBM (WHO grade 4; Table 1). The AM was used only for the comparison of the GEPs of fresh tissue versus cell culture.

Table 1.

Characteristics of tumor samples included in the study.

| Patient ID | Tumor type | WHO Grade | Location | Sex | Age (years) | Seizure | Fresh tissue sample RIN | Primary culture RIN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 168 | AM | II | Fronto-temporal region | F | 13 | No | 8.0 | 9.3 |

| 186 | PA | I | Cerebellum | M | 7 | No | 7.7 | 9.2 |

| 192 | PA | I | Cerebellum | M | 6 | No | 2.5 | 8.4 |

| 224 | AO | III | Right rolandic region | F | 30 | No | 8.2 | 9.5 |

| 232 | E | II | Right frontal region | F | 11 | No | 7.8 | N/A |

| 234 | GBM | IV | Giant, left hemisphere | F | 8 months | No | 6.9* | 9.1 |

| 250 | PA | I | Cerebellum | F | 11 | No | 6.2 | N/A |

| 1001 | AG | I | Left parieto-occipital region | F | 10 | Yes | 2.4 | 9.0 |

| 0102 | PA | I | Cerebellum | M | 20 | No | 2.2 | 9.5 |

| 1002 | PA | I | Cerebellum | M | 10 | No | 7.3 | 8.1 |

All the samples included in the study are reported. AO (sample 224), PA (sample 186), AM (sample 168), and PA (sample 1001) were used for the GEP comparison between fresh tissue samples and their derived primary cultures (see Figure 1). The other analysis referred to glioma cohort were carried out only on samples with the best RIN value (in bold) and were performed in all the tumor types listed in the Table, excepted for the meningioma (AM, sample 168). Abbreviations: PA, pilocytic astrocytoma; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; E, ependymoma; AM, atypical meningioma; AG, angiocentric glioma; F, female; M, male; N/A, not available.

*For the determination of GEP of GBM sample the fresh tissue was used in the bioinformatic analyses because, despite the best RIN value, the RNA obtained from the short-term culture was not sufficient to perform microarray experiment.

Primary cell cultures

The surgical fragment collected and maintained in PBS under sterile conditions was mechanically minced with sterile blades in 60 mm Petri dishes (Euroclone Ltd, Celbio, Italy) and transferred into 15 ml tubes (SARSTEDT S.R.L., Italy) containing Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12, Gibco-Invitrogen, Italy) and 0.25 mg/ml of type II collagenase. After incubating the minced tissue at 37°C for 5 min, cells were pelletted and resuspended in complete medium: DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, Italy) and antibiotics. Finally, the cell suspension was aliquoted into Petri dishes and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in air. Medium was replaced, after washing twice with PBS every 2 days, during the whole culture period (15 days maximum). Cultures were used for RNA extraction no later than 2 weeks following plating, to avoid over growth of mesenchymal cells.

CDNA microarray: RNA extraction, labeling, and hybridization

Total RNA was isolated by Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen S.R.L, Italy). RNA integrity was checked using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Italia, Italy), evaluating the RNA integrity number (RIN) of each sample (Schroeder et al., 2006). High quality quantified RNA was purified on silica gel columns using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (QIAGEN S.p.A., Italy). The quality of the purified RNA was confirmed by checking on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Germany). GEPs were determined using Agilent oligonucleotide microarray by one-color technology. About 500 ng of total RNA were used for each sample to generate cDNA probes. cDNA synthesis and labeling were performed by Agilent’s Quick Amp Labeling Kit. Hybridization was performed on human whole genome 44,000 oligonucleotide microarrays using reagents and protocols provided by the manufacturer (Agilent Technologies, Manual Part Number G4140-90042). The Feature extraction software (Agilent, version 9.5), was used to quantify the intensity of fluorescent images. The FirstChoice® Human Brain Reference RNA (Ambion, Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, USA) was used as a reference. The Ambion® FirstChoice® Human Brain Reference RNA is a high quality standard, suitable for human microarray analysis, pooled from different brain regions from 12 donors. The Reference RNA passes the strict quality control criteria for purity and integrity used for the MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project. FirstChoice® Human Brain Reference RNA is the same RNA (identical manufacturing lot) used for the MAQC project (MAQC Consortium, 2006).

Statistical analysis of microarray data

Data analysis was performed using R software version 2.11.01 by Bioconductor Packages2 using row images (dat files), as obtained from the Feature extraction analysis (see above). Data were normalized using “scale” normalization (Smyth and Speed, 2003) as implemented in “limma” package, made available on Bioconductor (see text footnote 2).

Comparison between fresh samples and primary cultures

The log 2 normalized values were used to evaluate differences in gene expression between fresh tissue samples and their derived primary cultures. Four different brain tumor samples of different histological types (including a non-glial tumor, e.g., one meningioma), and their corresponding short-term cultures, were analyzed: PA (sample 186), AO (sample 224), AM (sample 168), and PA (sample 1002). It is worth noting that when multiple arrays are being compared to each other, the raw data from all chips should be normalized together. A normalization between arrays, like scale normalization, assumes a common distribution for datasets. Our collection of samples is however heterogeneous, as it combines different patients and distinct pathologies. As such, it clearly displays a degree of intrinsic variability that should be carefully evaluated. On the other hand, in the following analysis, we were mainly interested in detecting those biological patterns that appear to be consistently altered in all recorded dataset, beyond the specific peculiarities that make each sample inherently different. Moreover, it can be argued that relatively few genes are DE across the different experiments, an a priori ansatz that one can subsequently validated. Inspired by this rationale, we proceeded with the aforementioned normalization strategy and checked a posteriori the correlation coefficients among scrutinized dataset. Interestingly, the correlation coefficients between the expression values obtained in the fresh tissue samples and the corresponding measures relative to the cell culture resulted in: PA (sample 186), 0.88; AO, 0.86; AM, 0.94; and PA (sample 1002), 0.90. The correlation coefficients among all other dataset returned values close to 0.8, so confirming on the whole our former assumption. In particular, cultured samples appear to preserve a large part of the biological information as contained in their original fresh homologs.

Analysis of DE genes

To perform the differential expression analysis, aimed to identify deregulated genes in gliomas, we considered the log 2 ratio of intensity values of each gene, respect to the corresponding intensity value in the control sample (normal brain). This analysis was therefore applied to nine samples, either fresh or culture, depending on the best RIN (see Table 1).

A One Sample t-test was applied to the log-ratios and a p-value was calculated for each gene. A Bonferroni procedure was applied to take into account the multiple testing correction. To pick out the DE genes we considered a threshold of 0.01 on the corrected p-value, plus an average cut off of fourfold changes.

Functional annotation analysis

Functional annotation analysis was performed using NIH-DAVID software (version 6.7)3. Our aim was to find the most relevant Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with DE genes. For this purpose, we used the parameter GOTERM_BP_FAT, and the significance p-value threshold was set <0.01, with Bonferroni multiple testing correction.

Results

Evaluation of differences in gene expression between fresh tissue samples and their derived short-term cultures

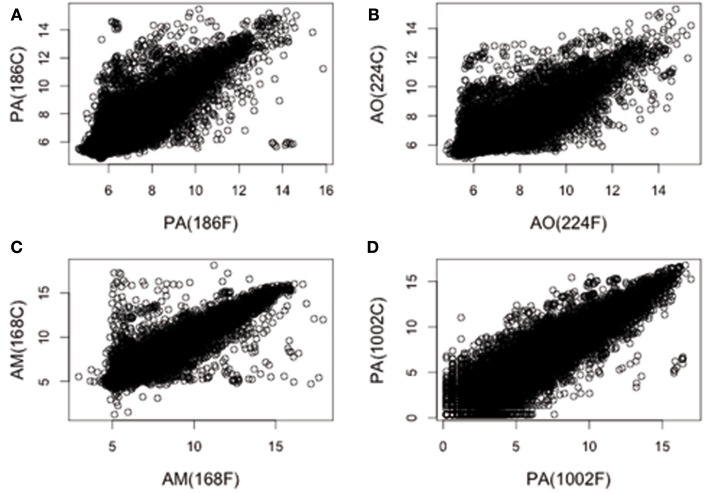

We first analyzed the GEPs of four fresh pediatric brain tumor samples of different histogenesis (see Materials and Methods) and their corresponding short-term culture (15 days). Thus, we determined whether the establishment and short-term maintenance of the cell culture would alter the GEP of the primary tissue sample. In Figure 1, the (normalized) gene expression values associated with the fresh tumor samples are plotted against the data obtained from the corresponding short-term cultures. Clearly, the two sets of data are positively correlated. This implied that the short-term culturing preserved a large portion of the original GEPs. On the other hand, and beyond the qualitative assessment, a dispersion around the idealized linear distribution was apparent (Figure 1). The latter observation reflected the inherent variability of the scrutinized samples, mainly due to the histopathological differences of tumors analyzed. In order to evaluate the data quantitatively, we calculated the correlation coefficient values between fresh tissue samples and the corresponding culture, applying the assumptions and the procedure described in Section “Materials and Methods.” The values thus obtained were: A: 0.88, B: 0.86, C: 0.94, and D: 0.90. Based on the above, we argued that cultured samples preserve a substantial degree of similarity with their fresh analogs. We concluded, therefore, that either primary tissue samples or their corresponding short-term cultures, could be used to perform cDNA microarray analyses. This allowed the use of either short-term cultures or primary tissue samples depending on best RIN value. On these bases, we performed cDNA microarray analyses of DE genes in the available cohort of pediatric gliomas (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of GEPs between fresh tissue samples and their derived primary cultures. The log 2 normalized values for each gene of fresh tissue pediatric brain tumors versus its primary culture are matched. In (A–D) are represented PA (sample 186), AO (sample 224), AM (sample 168), and PA (sample 1002) samples, respectively. The degree of similarity of each sample respect to its primary culture has been quantitatively explored by calculating the associated correlation coefficients. Average Pearson’s correlation coefficients were: (A), 0.88; (B), 0.86; (C), 0.94, and (D), 0.90.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes of gliomas compared to normal brain

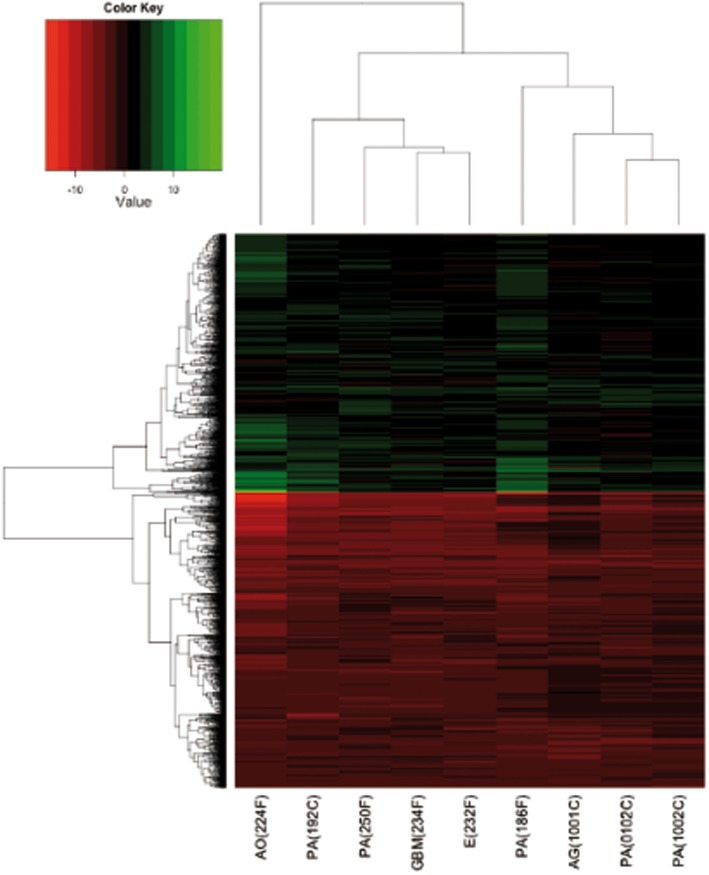

We determined the GEPs of nine gliomas, mainly LGGs (PAs, AG, AO, and E) and a GBM. Since the analysis mainly focused on glial-derived tumor, the AM sample was omitted. The Ambion® FirstChoice® Human Brain Reference RNA (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, USA), which derives from the pooling of 12 different donors and several brain regions, was used as the normal control reference. Although the tumor analyzed had different sites of presentation, we used a “whole brain” control sample, as previously described by Godard et al. (2003), to ensure a reproducible, tissue-specific reference. The expression profile of each gene was evaluated as detailed in Section “Materials and Methods.” In particular, a gene was assumed to be DE when the corrected p-value was lower than 0.01 and the fold change was ≥4. We obtained 2284 probes matching such requisites. The 2284 DE genes are shown in a cluster diagram in Figure 2 and are listed in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. About 1219 out of the 2284 DE genes (53%) were downregulated, whilst 1065 DE genes (47%) were upregulated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Heatmap of DE genes, performed, and plotted using “heatmap.2” function in R. Samples and genes (columns and rows respectively) are reordered on the basis of the average value of gene expression (log 2 ratio), and give rise to groups of genes and samples with similar average expression levels, according to the color key, shown on the top.

Functional annotation analysis of the glioma samples cohort

We next performed FAA on the microarray data of DE genes, based on GO terms enrichment, using the NIH-DAVID software. It emerged that the DE genes are significantly associated to 43 groups (called “terms”) of potential functional distinction (Table S2 in Supplementary Material). This type of analysis (Huang et al., 2009) identifies the most altered biological processes, regardless their up or down expression. Hence, we performed a second FAA, taking into account separately those genes that are up or downregulated.

Upregulated genes

The FAA on the DE genes that are overexpressed led to 61 enriched terms (Table 2; Table S3 in Supplementary Material). The majority of them belong to three main biological processes that can be summarized as follows: immune/inflammatory response, cell proliferation and survival, cellular adhesion and motility. Table 2 shows the upregulated terms divided into the three main biological processes identified. Some representative genes, with their median expression values (reported as fold change), are also reported.

Table 2.

Statistically significant biological processes, associated to the upregulated genes only, represented by DE GO terms in our cohort of glioma samples.

| Biological processes | GO terms | Representative genes | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune/inflammatory response | GO:0006955 ∼ immune response | C1QA | 2.25 |

| GO:0009611 ∼ response to wounding | ANXA1 | 3.61 | |

| GO:0006952 ∼ defense response | ANXA5 | 2.99 | |

| GO:0006954 ∼ inflammatory response | CTGF | 6.20 | |

| GO:0019882 ∼ antigen processing and presentation | CD163 | 3.12 | |

| GO:0042060 ∼ wound healing | NOTCH2 | 2.21 | |

| GO:0048002 ∼ antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen | CD44 | 3.13 | |

| GO:0010033 ∼ response to organic substance | STAT1 | 2.78 | |

| GO:0002684 ∼ positive regulation of immune system process | MYC | 2.75 | |

| GO:0046649 ∼ lymphocyte activation | COL1A1 | 6.72 | |

| GO:0002460 ∼ adaptive immune response based on somatic recombination of immune receptors built from immunoglobulin superfamily domains | IFI30 | 4.69 | |

| GO:0002250 ∼ adaptive immune response | CDKN1A | 2.26 | |

| GO:0042110 ∼ T cell activation | CDKN2A | 2.91 | |

| GO:0045321 ∼ leukocyte activation | ERBB2 | 2.48 | |

| GO:0002504 ∼ antigen processing and presentation of peptide or polysaccharide antigen via MHC class II | HBEGF | 3.13 | |

| GO:0045087 ∼ innate immune response | FN1 | 4.86 | |

| GO:0002694 ∼ regulation of leukocyte activation | |||

| GO:0002252 ∼ immune effector process | |||

| GO:0050778 ∼ positive regulation of immune response | |||

| GO:0051249 ∼ regulation of lymphocyte activation | |||

| GO:0006968 ∼ cellular defense response | |||

| GO:0002449 ∼ lymphocyte mediated immunity | |||

| Cell proliferation and survival | GO:0043067 ∼ regulation of programmed cell death | KCNMA1 (variant 2) | 2.53 |

| GO:0042127 ∼ regulation of cell proliferation | ANXA5 | 2.99 | |

| GO:0010941 ∼ regulation of cell death | ANXA1 | 3.61 | |

| GO:0042981 ∼ regulation of apoptosis | MMP9 | 6.35 | |

| GO:0043065 ∼ positive regulation of apoptosis | CD44 | 3.13 | |

| GO:0043068 ∼ positive regulation of programmed cell death | NOTCH2 | 2.21 | |

| GO:0010942 ∼ positive regulation of cell death | IFI30 | 4.69 | |

| GO:0006917 ∼ induction of apoptosis | STAT1 | 2.78 | |

| GO:0012502 ∼ induction of programmed cell death | MYC | 2.75 | |

| GO:0008285 ∼ negative regulation of cell proliferation | CDKN1A | 2.26 | |

| GO:0006915 ∼ apoptosis | CDKN2A | 2.91 | |

| GO:0008219 ∼ cell death | ERBB2 | 2.48 | |

| GO:0008284 ∼ positive regulation of cell proliferation | HBEGF | 3.13 | |

| GO:0016265 ∼ death | PIM1 | 2.76 | |

| GO:0012501 ∼ programmed cell death | |||

| GO:0043066 ∼ negative regulation of apoptosis | |||

| GO:0006916 ∼ anti-apoptosis | |||

| GO:0043069 ∼ negative regulation of programmed cell death | |||

| GO:0060548 ∼ negative regulation of cell death | |||

| Cellular adhesion and motility | GO:0006928 ∼ cell motion | ANXA1 | 3.61 |

| GO:0016477 ∼ cell migration | CTGF | 6.20 | |

| GO:0051674 ∼ localization of cell | CD44 | 3.13 | |

| GO:0048870 ∼ cell motility | MMP9 | 6.35 | |

| GO:0007155 ∼ cell adhesion | COL1A1 | 6.72 | |

| GO:0022610 ∼ biological adhesion | TGFBI | 6.98 | |

| GO:0030198 ∼ extracellular matrix organization | ANXA2P1 | 4.99 | |

| GO:0051270 ∼ regulation of cell motion | ANXA2 | 5.02 | |

| GO:0030334 ∼ regulation of cell migration | ERBB2 | 2.48 | |

| GO:0006935 ∼ chemotaxis | HBEGF | 3.13 | |

| GO:0042330 ∼ taxis | FN1 | 4.86 | |

| GO:0040012 ∼ regulation of locomotion |

Some representative genes are reported with the relative fold change.

Downregulated genes

Functional annotation analysis of these genes instead revealed 12 terms. Appling the same criteria of selection as in the FAA of upregulated genes, we found that they were mostly related to two main biological processes: neuronal phenotype and ion transport (Table 3; Table S4 in Supplementary Material). Table 3 shows the downregulated terms divided into the two main biological processes identified. Some representative genes, with their median expression values (reported as fold change), are also reported.

Table 3.

Statistically significant biological processes, associated to the downregulated genes only, represented by DE GO terms in our cohort of glioma samples.

| Biological processes | GO terms | Representative genes | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuronal phenotype | GO:0019226 ∼ transmission of nerve impulse | KCNMA1 (variant 1) | −2.82 |

| GO:0007268 ∼ synaptic transmission | SLC1A2 | −2.84 | |

| GO:0030182 ∼ neuron differentiation | SCN2B | −3.01 | |

| GO:0031644 ∼ regulation of neurological system process | SCN4B | −2.82 | |

| GO:0051969 ∼ regulation of transmission of nerve impulse | NEUROD2 | −7.74 | |

| GO:0050804 ∼ regulation of synaptic transmission | STMN2 | −8.49 | |

| GO:0048666 ∼ neuron development | |||

| Ion transport | GO:0030001 ∼ metal ion transport | KCNMA1 (variant 1) | −2.82 |

| GO:0006811 ∼ ion transport | CACN2D2 | −2.27 | |

| GO:0006812 ∼ cation transport | ATP1B1 | −4.60 | |

| SCN2B | −3.01 | ||

| SCN4B | −2.82 | ||

| SLC30A3 | −4.08 | ||

| ATP6V1G2 | −4.49 | ||

| ATP6V0C | −2.11 | ||

| SLC26A1 | −3.15 | ||

| SLCO4A1 | −2.45 | ||

| SLC4A3 | −2.52 |

Some representative genes are reported with the corresponding fold change.

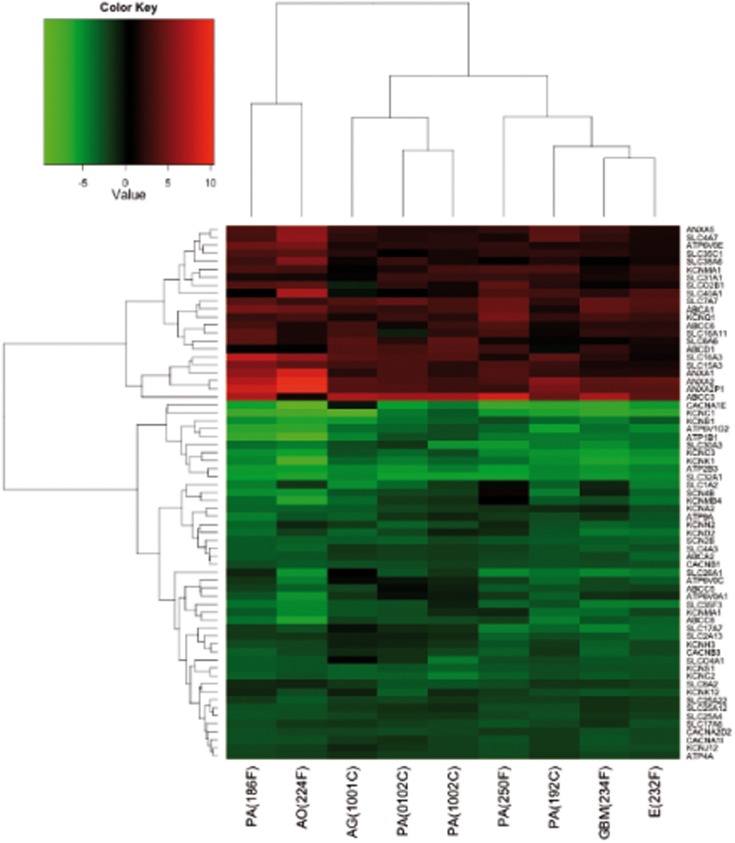

Analysis of DE genes associated to the transporter classification database

To further deepen the study of ion transport process, we performed a more focused analysis selecting, among the DE genes, the probes associated to ion channels, and transporters according to the readily available Transporter Classification Database for ion channels and transporters4. We thus identified 67 DE genes (Figure 3; Table S5 in Supplementary Material). Such genes included two main groups: those coding for transporters (n = 45; 67%) and those coding for ion channels (n = 22; 33%). Most of these genes encode solute carriers (SLC, n = 25), whereas other categories include potassium channels (n = 16), ATPases (n = 8), ATP-binding cassettes (ABC, n = 7), calcium channels (n = 5), annexins (ANXA, n = 4), and two sodium channel beta subunits. Thirty-three percentage of the 67 genes belonging to ion channels and transporters are upregulated and they are mainly transporters. On the other hand, among the downregulated genes, many (48%) belongs to ion channel encoding genes.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of DE genes associated to transporters and ion channels, performed, and plotted using “heatmap.2” function in R. Samples and genes (columns and rows respectively) are reordered on the basis of the average value of gene expression (log 2 ratio), and give rise to groups of genes and samples with similar average expression levels, according to the color key on the top.

Discussion

We have applied a method, previously developed for adult gliomas (Masi et al., 2005), to obtain short-term cultures of pediatric gliomas. This method proved to be suitable for cDNA microarray studies of pediatric brain tumors, where the availability of fresh primary samples is limited by surgical procedures and diagnostic necessities, as well as possible ethical constraints. Moreover, establishing tissue cultures providing a “pure” population of proliferating tumor cells makes it unnecessary to selectively isolate and capture malignant glial cells, for further analyses. Finally, the primary culture samples we analyzed often showed better RIN values (see Table 1), hence strongly influencing the decision whether to include or not a patient into a study. Indeed, when we plotted and calculated the correlation coefficients of the gene expression values associated with the fresh tumor samples against the data obtained from the corresponding short-term cultures, the two sets of data turned out to be positively correlated. This implied that the short-term culturing preserved a large portion of the original GEPs. This method, when applied routinely, could overcome possible molecular degradation and contamination by non-cancerous cells (although some differentiation or selection of unwanted cellular phenotypes could not be ruled out), which often biases molecular studies in primary tumor samples.

The short-term culture system allowed the molecular characterization of the tumors, and could be extended to further functional studies. In the present study we determined the GEPs of nine gliomas (mainly LGGs/PAs), a small number of samples, although compatible to those reported in recent studies (Wong et al., 2005; Faury et al., 2007; Kasuga et al., 2008). Almost half of the DE genes were upregulated, while the others were downregulated. The further FAA led us to identify terms of the DE genes in our samples. Besides being obtained with different biomolecular and analytical procedures, the genes we identified as DE belonged to terms almost identical to those reported in Wong et al. (2005) and Faury et al. (2007). This further stress the validity of the methods we applied in the present study.

In fact, that the terms comprising the overexpressed DE genes were mainly those concerned with immune/inflammatory response, control of proliferation/survival, and regulation of cell adhesion and migration.

In particular, the genes belonging to the immune/inflammatory response are represented by human leukocyte antigen (HLA, e.g., MHC) genes, mainly HLA-D genes. Since it is known that neurons under normal conditions inhibit MHC expression in glial cells (Tontsch and Rott, 1993), the overexpression of MHC genes in the tumor glia could be the consequence of neuronal damage leading to alteration of neuroglial contacts accompanied by the difficulty for neurites to establish contact with cells placed within the tumor mass. Alternatively, tumor astrocytes could become APC-like cells and thus upregulate their MHC II class expression as suggested earlier (Vidovic et al., 1990; Nair et al., 2008).

Among the upregulated genes, many growth factors (GFs) are comprised (Table 2; Table S1 in Supplementary Material). Interestingly, while GFs such as TGFBI, CTGF, VEGF, HBEGF, ERBB2, platelet derived GFs, insulin like GFs turned out to be overexpressed, fibroblast GFs, and their receptors were downregulated. This confirmed the accuracy of our short-term culture system, ruling out any contamination by mesenchymal cells. The deregulation of genes involved in proliferation and survival also involved cell cycle regulating genes, such as CDKN1A and CDKN2A. CDKN1A plays also a role in cell protection from apoptosis. Indeed, several other genes involved in different apoptotic pathways, presented altered regulation in our samples. For example, members of BCL families, regulatory genes such as MYC, STAT1, and NOTCH2 were all overexpressed in our tumor samples.

Moreover, many genes related to the extracellular matrix (ECM) turned out to be overexpressed in our samples. Among them, the matrix metalloproteinase (MPPs) MMP9 (6.35, as reported in Table 2; Table S1 in Supplementary Material) was highly overexpressed. MMPs upregulation followed the overexpression of genes that encode for ECM constituents such as collagens and fibronectin.

Significant downregulation of genes encoding neuronal phenotype and ion channels and transporters was apparent in the pediatric glioma cohort we studied. An overall downregulation of genes belonging to the “neuronal phenotype” could be expected, since we compared glial origin tumors with normal brain tissue. Nevertheless, the deregulation of ion channels and transporters merits more attention. In particular, it is interesting to note that most of the downregulated ion channel genes were voltage-gated potassium and calcium channels. This would suggest deregulation of glial cell excitability, as previously indicated (Verkhratsky and Steinhäuser, 2000; Sontheimer, 2008). Only two potassium channel encoding genes were upregulated, KCNQ1 (Barhanin et al., 1996) and KCNMA1, encoding the large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel, KCa1.1. KCa1.1 was upregulated in various type of tumors, mainly of glial origin (D’Amico et al., 2012). In the present cohort of pediatric gliomas, only the variant 2 isoform was upregulated, while the variant 1 isoform was downregulated. Interestingly, also CACNA2D2, encoding a calcium channel, was found to be downregulated, in agreement with Carboni et al. (2003) who identified CACNA2D2 as a putative tumor suppressor gene. Finally, the alteration in the expression level of SCN2B and SCN4B, encoding two sodium channel subunit beta, further stresses the relevance of sodium channels in gliomas, as recently reported by Joshi et al. (2011). Normal expression of K+ channels in astrocytes maintains an hyperpolarized potential which regulates buffering of extracellular K+, pH, and glutamate (Djukic et al., 2007; Olsen and Sontheimer, 2008). Our results show that generalized downregulation of K+ channels occurs in gliomas, in agreement with previous studies on specific channel types (e.g., Olsen and Sontheimer, 2008). The ensuing alteration of the peritumor space composition is likely enhanced by the concomitant decrease in the expression of electrogenic glutamate transporters (De Groot and Sontheimer, 2011) and several transporters implicated in pH regulation, such as the sodium bicarbonate cotransporters (e.g., Table S5 in Supplementary Material). These effects may contribute to explain the proneness to epileptic seizure development displayed by LGG patients, as higher extracellular K+, lower pH, and increased glutamate levels tend to produce neuronal hyperexcitability (Buckingham et al., 2011).

While downregulation of ion channels may decrease the functioning of glial cells (Verkhratsky and Steinhäuser, 2000), deregulation of gene encoding transporters might have more complex consequences, contributing to multidrug resistance (Carboni et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006), and/or enhanced cytotoxicity (Wakaumi et al., 2005; Blair et al., 2011). Moreover, the downregulation of genes encoding ion transporters, such as V-ATPase genes and SLC4A3 and SLC26A1 could strongly alter the pH homeostasis (Casey et al., 2009). Interestingly, the genes encoding for the SLC and ABC transporters were almost equally distributed between the up and the downregulated genes, whereas the ANXAs were upregulated and the ATPases were downregulated (except for the ATP6V0E transcript). The gene encoding ABCC6, which is involved in multidrug resistance, is one of the most strongly upregulated genes. Another transporter that merit attention is SLC1A2. SLC1A2 expression tends to decrease glioma cell proliferation (Krona, 2006), and we assume its downregulation could contribute to increase proliferation in our cohort of samples. Moreover, because SCL1A2 is the main responsible for clearing extracellular glutamate during excitatory synaptic activation in the central nervous system, downregulation of SLC1A2 may be a further contributor to seizure development (Simantov et al., 1999), as discussed above.

On the whole, determining the GEPs of individual patients could significantly affect the available therapeutic choices.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/Pediatric_Oncology/10.3389/fonc.2012.00053/abstract

Gene differentially expressed (DE) in gliomas compared to normal brain. About 2284 DE genes identified by One Sample t-test with a p-value < 0.01, fold change ≥4, and Bonferroni correction.

Functional annotation analyses (FAA) from all DE genes. FAA performed using NIH-DAVID software (version 6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) on all the DE genes reported in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. We used the parameter GOTERM_BP_FAT, with the significance p-value threshold set <0.01, with Bonferroni correction.

Functional annotation analysis from differentially overexpressed genes. FAA performed using NIH-DAVID software (version 6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) on the differentially overexpressed genes reported in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. We used the parameter GOTERM_BP_FAT, with the significance p-value threshold set <0.01, with Bonferroni correction.

Functional annotation analysis from differentially underexpressed genes. FAA performed using NIH-DAVID software (version 6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) on the differentially underexpressed genes reported in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. We used the parameter GOTERM_BP_FAT, with the significance p-value threshold set <0.01, with Bonferroni correction.

Differentially expressed genes associated to ion channels and transporters. Sixty-seven DE genes, associated to ion channels and transporters, identified by One Sample t-test with a p-value < 0.01, fold change ≥4, and Bonferroni correction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Associazione Genitori contro le Leucemie e Tumori Infantili “Noi per Voi,” the Fondazione Tommasino Bacciotti, the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), the Istituto Toscano Tumori (ITT), and the Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie, Linfomi e Mieloma (AIL Pistoia). The revision of the manuscript by Prof. M.B.A. Djamgoz (Neuroscience Solutions to Cancer Research Group, Imperial College London, London, UK) is kindly acknowledged.

Footnotes

References

- Arcangeli A., Crociani O., Lastraioli E., Masi A., Pillozzi S., Becchetti A. (2009). Targeting ion channels in cancer: a novel frontier in antineoplastic therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 16, 66–93 10.2174/092986709787002835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcangeli A., Yuan J. X. (2011). American journal of physiology-cell physiology theme: ion channels and transporters in cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 301, C253–C254 10.1152/ajpcell.00159.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvind S., Arivazhagan A., Santosh V., Chandramouli B. A. (2012). Differential expression of a novel voltage gated potassium channel – Kv 1.5 in astrocytomas and its impact on prognosis in glioblastoma. Br. J. Neurosurg. 26, 16–20 10.3109/02688697.2011.583365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhanin J., Lesage F., Guillemare E., Fink M., Lazdunski M., Romey G. (1996). KvLQT1 and IsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKs cardiac potassium current. Nature 384, 78–80 10.1038/384078a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair B. G., Larson C. A., Adams P. L., Abada P. B., Pesce C. E., Safaei R., Howell S. B. (2011). Copper transporter 2 regulates endocytosis and controls tumor growth and sensitivity to cisplatin in vivo. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 157–166 10.1124/mol.110.068411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredel M., Bredel C., Juric D., Harsh G. R., Vogel H., Recht L. D., Sikic B. I. (2005). High-resolution genome-wide mapping of genetic alterations in human glial brain tumors. Cancer Res. 65, 4088–4096 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccoliero A. M., Caldarella A., Ammannati F., Mennonna P., Taddei A., Taddei G. L. (2002). Extraventricular neurocytoma: morphological and immunohistochemical considerations on differential diagnosis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 198, 627–633; discussion 635–638. 10.1078/0344-0338-00186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham S. C., Campbell S. L., Haas B. R., Montana V., Robel S., Ogunrinu T., Sontheimer H. (2011). Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nat. Med. 17, 1269–1274 10.1038/nm.2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni G. L., Gao B., Nishizaki M., Xu K., Minna J. D., Roth J. A., Ji L. (2003). CACNA2D2-mediated apoptosis in NSCLC cells is associated with alterations of the intracellular calcium signaling and disruption of mitochondria membrane integrity. Oncogene 22, 615–626 10.1038/sj.onc.1206134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J. R., Grinstein S., Orlowski J. (2009). Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 50–61 10.1038/nrm2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Watson J. T., Marengo S. R., Decker K. S., Coleman I., Nelson P. S., Sikes R. A. (2006). Gene expression in the LNCaP human prostate cancer progression model: progression associated expression in vitro corresponds to expression changes associated with prostate cancer progression in vivo. Cancer Lett. 244, 274–288 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddapah V. A., Sontheimer H. (2011). Ion channels and transporters [corrected] in cancer. 2. Ion channels and the control of cancer cell migration. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 301, C541–C549 10.1152/ajpcell.00102.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico M., Gasparoli L., Arcangeli A. (2012). Potassium channels: novel emerging biomarkers and targets for therapy in cancer. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bont J. M., Kros J. M., Passier M. M. C. J., Reddingius R. E., Sillevis Smitt P. A. E., Luider T. M., den Boer M. L., Pieters R. (2008). Differential expression and prognostic significance of SOX genes in pediatric medulloblastoma and ependymoma identified by microarray analysis. Neuro-oncology 10, 648–660 10.1215/15228517-2008-059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J., Sontheimer H. (2011). Glutamate and the biology of gliomas. Glia 59, 1181–1189 10.1002/glia.21113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukic B., Casper K. B., Philpot B. D., Chin L.-S., McCarthy K. D. (2007). Conditional knock-out of Kir4.1 leads to glial membrane depolarization, inhibition of potassium and glutamate uptake, and enhanced short-term synaptic potentiation. J. Neurosci. 27, 11354–11365 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0723-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuc A. M., Northcott P. A., Mack S., Witt H., Pfister S., Taylor M. D. (2010). The genetics of pediatric brain tumors. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 10, 215–223 10.1007/s11910-010-0103-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faury D., Nantel A., Dunn S. E., Guiot M. C., Haque T., Hauser P., Garami M., Bognár L., Hanzély Z., Liberski P. P., Lopez-Aguilar E., Valera E. T., Tone L. G., Carret A. S., Del Maestro R. F., Gleave M., Montes J. L., Pietsch T., Albrecht S., Jabado N. (2007). Molecular profiling identifies prognostic subgroups of pediatric glioblastoma and shows increased YB-1 expression in tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 10, 1196–1208 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freije W. A., Castro-Vargas F. E., Fang Z., Horvath S., Cloughesy T., Liau L. M., Mischel P. S., Nelson S. F. (2004). Gene expression profiling of gliomas strongly predicts survival. Cancer Res. 64, 6503–6510 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godard S., Getz G., Delorenzi M., Farmer P., Kobayashi H., Desbaillets I., Nozaki M., Diserens A. C., Hamou M. F., Dietrich P. Y., Regli L., Janzer R. C., Bucher P., Stupp R., de Tribolet N., Domany E., Hegi M. E. (2003). Classification of human astrocytic gliomas on the basis of gene expression: a correlated group of genes with angiogenic activity emerges as a strong predictor of subtypes. Cancer Res. 63, 6613–6625 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. (2009). Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A. D., Parsons D. W., Velculescu V. E., Riggins G. J. (2011). Sodium ion channel mutations in glioblastoma patients correlate with shorter survival. Mol. Cancer 11, 10–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga C., Nakahara Y., Ueda S., Hawkins C., Taylor M. D., Smith C. A., Rutka J. T. (2008). Expression of MAGE and GAGE genes in medulloblastoma and modulation of resistance to chemotherapy. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 1, 305–313 10.3171/PED/2008/1/4/305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschny R., Koschny T., Froster U. G., Krupp W., Zuber M. A. (2002). Comparative genomic hybridization in glioma: a meta-analysis of 509 cases. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 135, 147–159 10.1016/S0165-4608(01)00650-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krona A. (2006). Gene Expression Studies in Human Astrocytoma, with Emphasis on Oncostatin M Induced Effects. Sweden: LIBRIS – National Library Systems [Google Scholar]

- Lee W., Glaeser H., Smith L. H., Roberts R. L., Moeckel G. W., Gervasini G., Leake B. F., Kim R. B. (2005). Polymorphisms in human organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1A2 (OATP1A2): implications for altered drug disposition and central nervous system drug entry. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9610–9617 10.1074/jbc.M503182200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis D. N., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O. D., Cavenee W. K., Burger P. C., Jouvet A., Scheithauer B. W., Kleihues P. (2007). The 2007 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 114, 97–109 10.1007/s00401-007-0278-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi A., Becchetti A., Restano-Cassulini R., Polvani S., Hofmann G., Buccoliero A. M., Paglierani M., Pollo B., Taddei G. L., Gallina P., Di Lorenzo N., Franceschetti S., Wanke E., Arcangeli A. (2005). hERG1 channels are overexpressed in glioblastoma multiforme and modulate VEGF secretion in glioblastoma cell lines. Br. J. Cancer 93, 781–792 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimino M., Cohen K. J., Finlay J. L. (2010). Is there a role for myeloablative chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic cell rescue in the management of childhood high-grade astrocytomas? Pediatr. Blood Cancer 54, 641–643 10.1002/pbc.22375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAQC Consortium (2006). The MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project shows inter- and intraplatform reproducibility of gene expression measurements. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1151–1161 10.1038/nbt1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel P. S., Cloughesy T. F., Nelson S. F. (2004). DNA-microarray analysis of brain cancer: molecular classification for therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 782–792 10.1038/nrn1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair A., Frederick T. J., Miller S. D. (2008). Astrocytes in multiple sclerosis: a product of their environment. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2702–2720 10.1007/s00018-008-8059-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen M. L., Sontheimer H. (2008). Functional implications for Kir4.1 channels in glial biology: from K+ buffering to cell differentiation. J. Neurochem. 107, 589–601 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05615.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paugh B. S., Qu C., Jones C., Liu Z., Adamowicz-Brice M., Zhang J., Bax D. A., Coyle B., Barrow J., Hargrave D., Lowe J., Gajjar A., Zhao W., Broniscer A., Ellison D. W., Grundy R. G., Baker S. J. (2010). Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 3061–3068 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack I. F., Hamilton R. L., James C. D., Finkelstein S. D., Burnham J., Yates A. J., Holmes E. J., Zhou T., Finlay J. L., Children’s Oncology Group (2006). Rarity of PTEN deletions and EGFR amplification in malignant gliomas of childhood: results from the Children’s Cancer Group 945 cohort. J. Neurosurg. 105(Suppl. 5), 418–424 10.3171/jns.2006.105.3.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preussat K., Beetz C., Schrey M., Kraft R., Wölfl S., Kalff R., Patt S. (2003). Expression of voltage-gated potassium channels Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 in human gliomas. Neurosci. Lett. 346, 33–36 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00562-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qaddoumi I., Sultan I., Gajjar A. (2009). Outcome and prognostic features in pediatric gliomas: a review of 6212 cases from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer 115, 5761–5770 10.1002/cncr.24663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J., Ai L., Ramachandran C., Yao B., Gopalakrishnan S., Fields C. R., Delmas A. L., Dyer L. M., Melnick S. J., Yachnis A. T., Schwartz P. H., Fine H. A., Brown K. D., Robertson K. D. (2008). Invasion suppressor cystatin E/M (CST6): high-level cell type-specific expression in normal brain and epigenetic silencing in gliomas. Lab. Invest. 88, 910–925 10.1038/labinvest.2008.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickert C. H., Sträter R., Kaatsch P., Wassmann H., Jürgens H., Dockhorn-Dworniczak B., Paulus W. (2001). Pediatric high-grade astrocytomas show chromosomal imbalances distinct from adult cases. Am. J. Pathol. 158, 1525–1532 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64103-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorive S., Maris C., Debeir O., Sandras F., Vidaud M., Bièche I., Salmon I., Decaestecker C. (2006). Exploring the distinctive biological characteristics of pilocytic and low-grade diffuse astrocytomas using microarray gene expression profiles. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 65, 794–807 10.1097/01.jnen.0000228203.12292.a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder A., Mueller O., Stocker S., Salowsky R., Leiber M., Gassmann M., Lightfoot S., Menzel W., Granzow M., Ragg T. (2006). The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol. Biol. 7, 3. 10.1186/1471-2199-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamji M. F., Fric-Shamji E. C., Benoit B. G. (2009). Brain tumors and epilepsy: pathophysiology of peritumoral changes. Neurosurg. Rev. 32, 275–285 10.1007/s10143-009-0191-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simantov R., Crispino M., Hoe W., Broutman G., Tocco G., Rothstein J. D., Baudry M. (1999). Changes in expression of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters in rat hippocampus following kainate-induced seizure activity. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 65, 112–123 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00349-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G. K., Speed T. (2003). Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31, 265–273 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00155-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer H. (2008). An unexpected role for ion channels in brain tumor metastasis. Exp. Biol. Med. 233, 779–791 10.3181/0711-MR-308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontsch U., Rott O. (1993). Intercellular regulation of major histocompatibility complex class I expression in neural cells. Immunology 80, 507–509 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A., Steinhäuser C. (2000). Ion channels in glial cells. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 32, 380–412 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00093-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidovic M., Sparacio S. M., Elovitz M., Benveniste E. N. (1990). Induction and regulation of class II major histocompatibility complex mRNA expression in astrocytes by interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Neuroimmunol. 30, 189–200 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90103-T [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vital A. L., Tabernero M. D., Castrillo A., Rebelo O., Tão H., Gomes F., Nieto A. B., Resende Oliveira C., Lopes M. C., Orfao A. (2010). Gene expression profiles of human glioblastomas are associated with both tumor cytogenetics and histopathology. Neuro-oncology 12, 991–1003 10.1093/neuonc/noq050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakaumi M., Ishibashi K., Ando H., Kasanuki H., Tsuruoka S. (2005). Acute digoxin loading reduces ABCA8A mRNA expression in the mouse liver. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 32, 1034–1041 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire R. N., Herndon J. E., II, Lloyd A., Friedman H. S., Bigner D. D., Bigner S. H., McLendon R. E. (2004). Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of astrocytomas: prognostic and diagnostic implications. J. Mol. Diagn. 6, 166–179 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60507-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K. K., Chang Y. M., Tsang Y. T., Perlaky L., Su J., Adesina A., Armstrong D. L., Bhattacharjee M., Dauser R., Blaney S. M., Chintagumpala M., Lau C. C. (2005). Expression analysis of juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas by oligonucleotide microarray reveals two potential subgroups. Cancer Res. 65, 76–84 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gene differentially expressed (DE) in gliomas compared to normal brain. About 2284 DE genes identified by One Sample t-test with a p-value < 0.01, fold change ≥4, and Bonferroni correction.

Functional annotation analyses (FAA) from all DE genes. FAA performed using NIH-DAVID software (version 6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) on all the DE genes reported in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. We used the parameter GOTERM_BP_FAT, with the significance p-value threshold set <0.01, with Bonferroni correction.

Functional annotation analysis from differentially overexpressed genes. FAA performed using NIH-DAVID software (version 6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) on the differentially overexpressed genes reported in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. We used the parameter GOTERM_BP_FAT, with the significance p-value threshold set <0.01, with Bonferroni correction.

Functional annotation analysis from differentially underexpressed genes. FAA performed using NIH-DAVID software (version 6.7, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) on the differentially underexpressed genes reported in Table S1 in Supplementary Material. We used the parameter GOTERM_BP_FAT, with the significance p-value threshold set <0.01, with Bonferroni correction.

Differentially expressed genes associated to ion channels and transporters. Sixty-seven DE genes, associated to ion channels and transporters, identified by One Sample t-test with a p-value < 0.01, fold change ≥4, and Bonferroni correction.