Abstract

Highly potent and selective small molecule Neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor antagonists are reported. The systematic SAR exploration of a hit molecule N-(4-ethoxyphenyl)-4-[hydroxy(diphenyl)methyl]piperidine-1-carbothioamide, identified from HTS, led to the discovery of highly potent NPY Y2 antagonists 16 (CYM 9484) and 54 (CYM 9552) with IC50 values of 19 nM and 12 nM respectively.

Keywords: Neuropeptie Y Y2, Antagonist, Structure Activity Relationship, Thiourea, Carbamate

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is a highly conserved 36-amino acid peptide neurotransmitter, structurally and functionally related to the 36-amino acid pancreatic peptide (PYY) and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) and one of the most abundant neuropeptides in the mammalian brain.1,2 NPY is involved in a variety of physiological processes such as regulation of energy balance, anxiety, food intake, water consumption, circadian rhythms, learning, memory, anxiety, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis.3–6 Four different receptor subtypes7,8 (Y1, Y2, Y4, Y5) have been identified as endogenous receptors in humans that bind to NPY and are expressed in both the central and peripheral nervous systems. All NPY receptor subtypes belong to the family of G protein coupled receptors (GPCR) and mediate their biological responses via Gαi signaling pathways.

The NPY Y2 receptor has attracted considerable interest since it has been associated with various physiological and pathological processes such as affective disorders, infertility, bone mass formation, responses to ethanol and drugs of abuse, angiogenesis, and food intake.9 Doods et al10 reported a highly potent (IC50 = 3.3 nM) peptide-like NPY Y2 antagonist BIIE0246, which decreased ethanol consumption in rats and induced antidepressant-like effects in mice11 following intracerebroventricular (icv) administration. However, the potential therapeutic application of this compound is limited due to its peptide-like structure, high molecular weight, poor brain penetration and off-target selectivity.12,13 While most of the efforts in the literature have been focused on the discovery and development of NPY Y1 and Y5 receptor antagonists as potential therapeutic agents for obesity and feeding disorders, there are only few reports on the identification of selective NPY Y2 receptor antagonists.14–18 Therefore, selective NPY Y2 antagonists with good physicochemical properties, suitable for in vivo studies are desired.

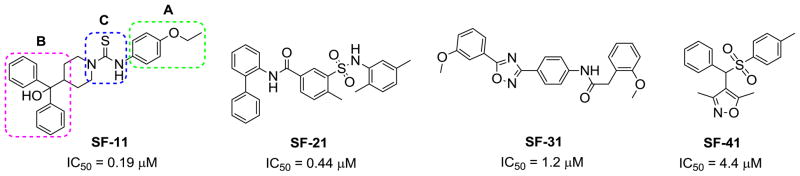

With an aim to identify selective, brain-penetrant, non-peptidic NPY Y2 antagonists that are suitable for in vivo studies, we performed whole-cell based high throughput screening of a library of small molecules available through the auspices of the National Institutes of Health. From the screening, we identified four distinct chemotypes (SF-11, SF-21, SF-31 and SF-41) that are novel, brain-penetrant, and selective against the NPY Y1 and 38 off-target receptors, including GPCRs, transporters and ion-channels.19 The four chemotypes (Figure 1) exhibited antagonism at the NPY Y2 receptor with IC50 values ranging from 0.19 to 4.4 μM. The hits are being followed up to further improve the potency, brain-penetration and drug-likeness. Here, we report the synthesis and SAR investigations of one of the hit molecules SF-11.

Figure 1.

Structures of four different chemotypes identified from HTS.

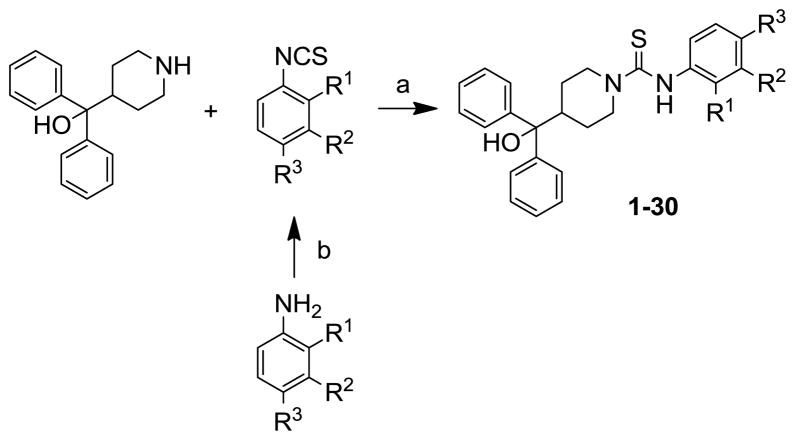

The hit molecule SF-11 was divided into three parts A (phenyl ring), B (diphenylcarbinol) and C (linker) to explore the SAR systematically (Figure 1). The preliminary SAR, observed from a tiny set of SF-11 analogues from the HTS campaign, indicated that the NPY Y2 antagonist activity may depend on both the position and type of the substituent present on the phenyl ring (A).19 Therefore, we have primarily explored the substitution on the aryl ring (A). The desired analogues (1–30, Table 1) were prepared by the coupling of commercially available α,α-diphenylpiperidino-4-methanol with a variety of aryl isothiocyanates (Scheme 1). The non-commercially available aryl isothiocyanates were prepared from appropriate anilines and thionating reagent di-2-pyridyl thionocarbonate.20 All compounds were determined to be >95% pure by 1H NMR and LC-MS.21 The compounds were tested against NPY Y2 and Y1 receptors using the cAMP biosensor assay as previously described.19 The activity data is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exploration of substitutions on the phenyl ring (A)

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | R2 | R3 | Y2 IC50a (μM) |

| SF-11 | H | H | OC2H5 | 0.199 |

| 1 | H | H | H | NA |

| 2 | H | H | OCH3 | 1.1 |

| 3 | H | H | OiPr | 1.77 |

| 4 | H | H | OCF3 | 1.047 |

| 5 | H | H | nC3H7 | 0.777 |

| 6 | H | H | CF3 | 0.178 |

| 7 | H | H | N(CH3)2 | 0.612 |

| 8 | H | H | N(C2H5)2 | 0.072 |

| 9 | H | H | Pyrrolidin-1-yl | 1.2 |

| 10 | H | H | Piperidin-1-yl | 0.271b |

| 11 | H | H | CO2C2H5 | 0.207 |

| 12 | H | H | CONHCH3 | 1.419 |

| 13 | H | H | CONHC2H5 | 0.206 |

| 14 | H | H | CON(CH3)2 | 0.301 |

| 15 | H | H | CON(C2H5)2 | 0.078 |

| 16 | H | H | SO2N(CH3)2 | 0.019 |

| 17 | H | H | SO2N(C2H5)2 | 0.136 |

| 18 | H | H | SO2-pyrrolidin-yl | 0.117 |

| 19 | H | H | SO2NHC2H5 | 0.121 |

| 20 | H | OCH3 | H | 8.162b |

| 21 | H | CF3 | H | NA |

| 22 | H | CO2C2H5 | H | 0.238b |

| 23 | H | CF3 | OCH3 | 6.079b |

| 24 | H | Cl | N(C2H5)2 | 0.085 |

| 25 | H | CN | OC2H5 | 0.323 |

| 26 | H | CN | OiPr | 0.899 |

| 27 | CH3 | H | OC2H5 | NA |

| 28 | CF3 | H | OC2H5 | NA |

| 29 | Cl | H | CF3 | NA |

| 30 | F | H | OC2H5 | 1.35 |

All compounds were inactive at NPY Y1 receptor; the highest concentration tested in the assay was 10 μM, (NA = not active);

exhibited partial antagonism.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CH2Cl2, rt, 2–3 h; (b) di-2-pyridyl thionocarbonate, CH2Cl2, rt, 2 h.

To determine the minimal structural requirements for the antagonist activity, the ethoxy group of the hit molecule SF-11 was removed as exemplified by 1, which resulted in complete loss of activity, suggesting a substitution on the aryl ring is essential. The replacement of the ethoxy group with a methoxy (2), isopropoxy (3) or trifluoromethoxy (4) resulted in decreased potency, which indicates the presence of a hydrophobic pocket with steric-constraints at the binding site. Interestingly, the n-propyl analogue 5 was less potent than the ethoxy analogue SF-11, suggesting the presence of both a hydrogen-bond acceptor and optimal hydrophobic group at this position would improve the antagonist activity. We have consequently investigated a variety of hydrogen-bond acceptor containing groups such as dialkylamines, esters, carboxamides, and sulfonamides. The diethylamine analogue 8 showed nearly 3-fold increase in the potency compared to SF-11. The dimethyl amine analogue 7, as well as cyclic amines 9 and 10 were less potent than the diethyl amine analogue 8 and SF-11, corroborating the SAR. The ethyl ester analogue 11 and ethyl amide analogue 13 exhibited similar potency to SF-11. The N,N-dialkylamide analogues 14 and 15 were more potent than the monoalkylamides 12 and 13, of which N,N-diethylamide analogue 15 was 4-fold more potent than N,N-dimethylamide analogue 14. In contrast to N,N-dialkylamide analogues 14 and 15, N,N-dimethyl sulfonamide analogue 16 (CYM 9484) displayed higher potency (IC50 = 19 nM) than N,N-diethyl sulfonamide analogue 17 and was 10-fold more potent than the hit molecule SF-11.

The importance of the position of the substituent on the phenyl ring (A) was studied subsequently. The 3-substituted analogues 20 and 21 were less potent than the corresponding 4-substituted analogues 2 and 6, except compound 22 which displayed similar potency to 11, but exhibited partial antagonism. To understand the effect of an additional substituent on the antagonist activity, we also explored 3, 4- and 2, 4-disubstitutions on the phenyl ring (A) as exemplified by 23–30. The chloro (24) and cyano (25 and 26) groups were tolerated at the 3-position, but did not improve the potency significantly compared to the corresponding 4-substittuted analogues 8, SF-11 and 3. The incorporation of methyl (27), trifluoromethyl (28) and chloro (29) groups at the 2-position resulted in complete loss of activity, whereas the fluoro (30) group was tolerable, but nearly 7-fold less potent than the corresponding analogue SF-11. The SAR exploration of groups on phenyl ring (A) suggests that a substitution at the 4-position of phenyl ring is important for antagonist activity, of which the N,N-dimethyl sulfonamide group is optimal.

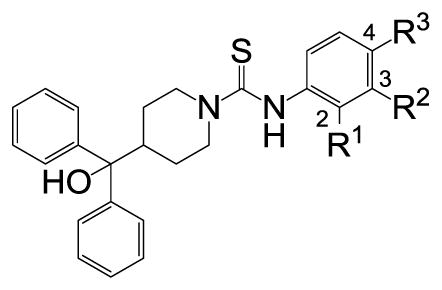

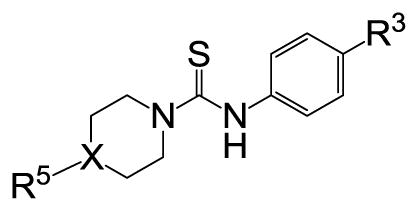

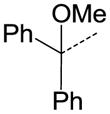

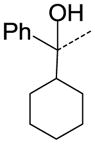

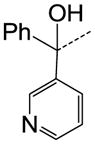

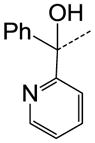

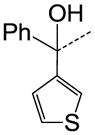

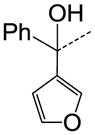

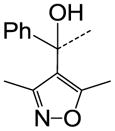

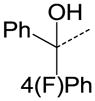

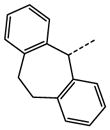

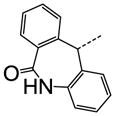

We then performed SAR studies on the diphenylcarbinol (B) of the hit molecule (Table 2). The removal of either one of the phenyl rings (31) or hydroxyl group of the diphenylcarbinol (34–36) was detrimental to the activity. The hydroxyl group was methylated to identify the necessity of a hydrogen-bond donor for the antagonist activity. The methylated analogue 35 displayed no activity, signifying the essentiality of a hydrogen-bond donor. Interestingly, the piperazine analogue 36 retained the activity in contrast to the piperidine analogue 32, supporting the requirement of a hydrogen-bond donor. Subsequently, we focused our efforts on modification of one of the phenyl rings of the diphenylcarbinol. The replacement of one of the phenyl rings with a cyclohexyl group (38) resulted in complete loss of activity. The heteroaryl analogues such as pyridin-2-yl 40 and thiophen-3-yl 41 were tolerable, whereas the furan-3-yl 42, 3-pyridin-3-yl 39 and 3,5-dimethylisoxazol-4-yl 43 analogues significantly lost the activity. The substitution of a fluorine at the 4-position (44) of one of the phenyl rings of diphenylcarbinol was tolerable, but not beneficial. We also explored the conformationally-constrained tricyclic moieties as exemplified by 45 and 46 to investigate the conformational requisite of the phenyl rings of diphenylcarbinol. Notably, the dibenzoazepinone analogue 46 displayed higher potency than the corresponding analogue 37, whereas the less-constrained tricyclic analogue 45 was inactive. The SAR studies of part B of the hit molecule suggest that a hydrogen-bond donor and the conformation of phenyl rings of diphenylcarbinol are important for the antagonist activity.

Table 2.

SAR exploration of the part B.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R5 | X | R3 | Y2 IC50a (μM) |

| 31 |

|

CH | OC2H5 | NA |

| 32 |

|

CH | OC2H5 | >10 |

| 33 |

|

CH | COOC2H5 | 6.76 |

| 34 |

|

C | OC2H5 | NA |

| 35 |

|

CH | SO2N(CH3)2 | NA |

| 36 |

|

N | OC2H5 | 0.371 |

| 37 |

|

N | SO2N(CH3)2 | 0.483 |

| 38 |

|

CH | OC2H5 | NA |

| 39 |

|

CH | SO2N(CH3)2 | NA |

| 40 |

|

CH | SO2N(CH3)2 | 0.098 |

| 41 |

|

CH | SO2N(CH3)2 | 0.248 |

| 42 |

|

CH | SO2N(CH3)2 | NA |

| 43 |

|

CH | OC2H5 | 3.3 |

| 44 |

|

CH | SO2N(CH3)2 | 0.089 |

| 45 |

|

N | SO2N(CH3)2 | NA |

| 46 |

|

N | SO2N(CH3)2 | 0.067 |

All compounds were inactive at NPY Y1 receptor; the highest concentration tested in the assay was 10 μM, (NA = not active).

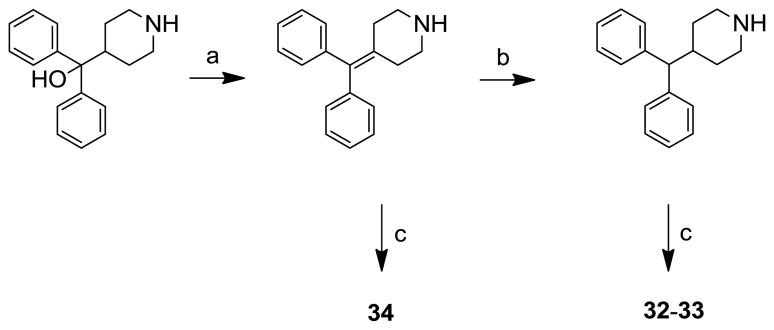

The synthesis of analogues 32–34 was carried out as shown in scheme 2. Dehydration of commercially available α,α-diphenylpiperidino-4-methanol using TFA gave the 4-(diphenylmethylene)piperidine, which was then reduced with trimethyl silane to yield the 4-benzhydrylpiperidine. Both, 4-(diphenylmethylene)piperidine and 4-benzhydrylpiperidine were coupled with aryl isothiocyanates to yield the target compounds 32–34.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) TFA, CH2Cl2, rt, 6 h; (b) (CH3)3SiH, CH2Cl2, 3 days, rt; (c) aryl isothiocyanate, CH2Cl2, rt, 2–3 h

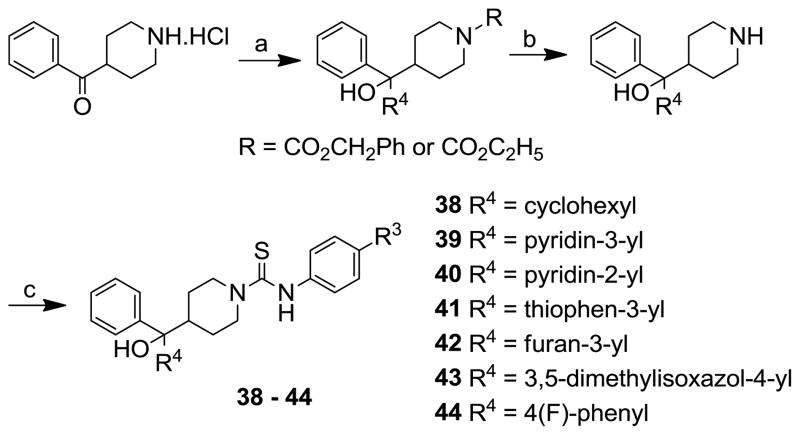

The synthesis of analogues 38–44 is outlined in scheme 3. The addition of cyclohexyl or various heteroaryl groups to the benzyl or ethyl-4-benzoylpiperidine-1-carboxylate was achieved by reacting with cyclohexylmagnesium bromide or heteroaryl lithiums that were generated in situ by treating the appropriate heteroaryl bromides with n-BuLi. The resulting benzyloxycarbonyl- or ethoxycarbonyl- protected 4-bis-arylcarbinolpiperidines, after deprotection by hydrogenation using Pd/C or basic conditions using K2CO3, were reacted with appropriate aryl isothiocyanates to afford the target compounds.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) i) ethyl or benzylchloroformate, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, 12 h; ii) cyclohexylmagnesium bromide, THF, −78 °C, 1 h or heteroaryl bromide, THF, n-BuLi, −78 °C, 30 min, then addition of ketones, −78 °C, 3 h; (b) H2, 10% Pd/C, MeOH, 3 h or K2CO3, MeOH, reflux, 24 h; (c) aryl isothiocyanate, CH2Cl2, 2–3 h, rt.

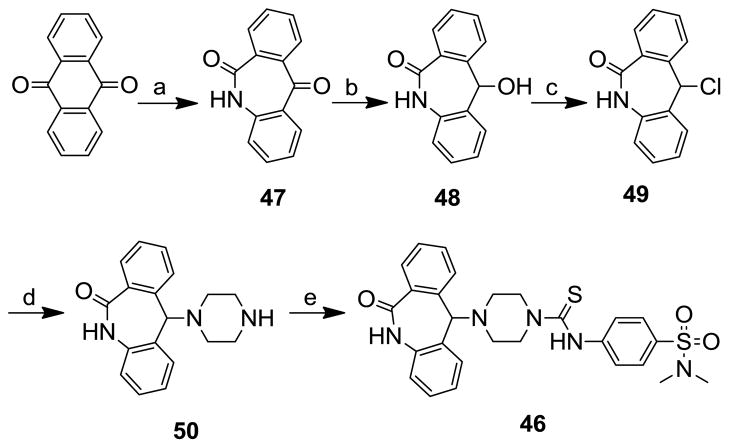

Compound 46 was prepared according to the scheme 4. The anthraquinone was transformed into 5H-dibenzo[b,e]azepine-6,11-dione22 (47), by treating with conc. H2SO4 and NaN3, which was then reduced to the alcohol 48 with sodium borohydride in MeOH. The resulting alcohol 48 was converted into the chloro derivative, 11-chloro-5H-dibenzo[b,e]azepin-6(11H)-one (49) by refluxing in thionyl chloride. The chloro group of the corresponding compound was displaced with piperazine using microwave irradiation to obtain 11-piperazin-1-yl-5,11-dihydrodibenzo[b,e]azepine-6-one (50), which was subsequently reacted with 4-isothiocyanato-N,N-dimethylbenzenesulfonamide to afford the desired compound 46. Compound 45 was prepared similarly to compound 46, starting from commercially available 5-chloro-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d][7]annulene.

Scheme 4.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaN3, H2SO4, CHCl3, reflux, 12 h; (b) NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 3 h; (c) SOCl2, CHCl3, reflux, 4 h; (d) piperazine, iPr2EtN, DMF, 145 °C, microwave, 1 h; (e) 4-isothiocyanato-N,N-dimethylbenzenesulfonamide, CH2Cl2, rt, 3 h.

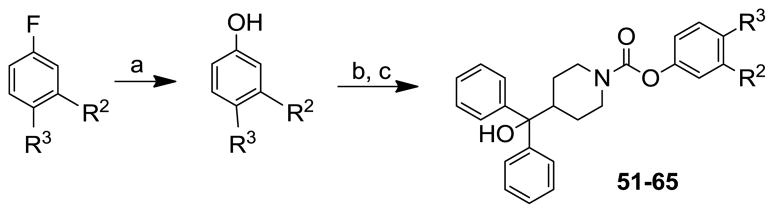

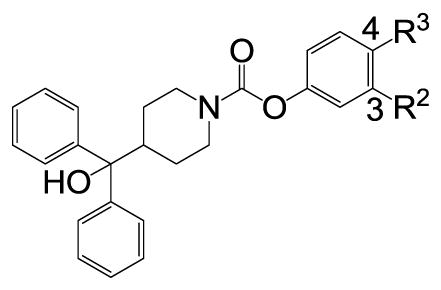

We subsequently modified the thiourea linker (C) of the hit molecule by replacing it with urea and carbamate functionalities. A variety of urea derivatives (not shown) that had different groups at 4-position of phenyl ring (A) were prepared and found to be inactive at 10 μM. Notably, the carbamate linker was very well tolerated (Table 3). In the carbamate series, we explored the groups that were good in the thiourea series at the 4-position of phenyl ring (A). In contrast to the thiourea series, the N,N-diethylsulfonamide analogue 54 (CYM 9552) was more potent (IC50 = 12 nM) than its corresponding N,N-dimethylsulfonamide analogue 53. The N,N-diethylamide analogue 60 was 18-fold less potent than the N,N-diethyl sulfonamide analogue 54. We also explored sulfones 56–59 at the 4-position, which displayed similar potency to the corresponding sulfonamide analogues 53 and 54. While the reverse sulfonamide analogue 63 retained the antagonist activity, the reverse carboxamide analogues 61 and 62 completely lost the activity. The 3-substituted analogues 64 and 65 displayed no activity, which suggests that in both the carbamate and thiourea series the substitution at the 4-position of phenyl ring (A) is important for the antagonist activity.

Table 3.

SAR of the carbamate analogues.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R2 | R3 | Y2 IC50a (μM) |

| 51 | H | OCH3 | 2.68 |

| 52 | H | OC2H5 | 1.58 |

| 53 | H | SO2N(CH3)2 | 0.061 |

| 54 | H | SO2N(C2H5)2 | 0.012 |

| 55 | H | SO2-pyrrolidine | 0.049 |

| 56 | H | SO2CH3 | 0.141 |

| 57 | H | SO2C2H5 | 0.059 |

| 58 | H | SO2(CH3)2 | 0.057 |

| 59 | H | SO2(C2H5)2 | 0.043 |

| 60 | H | CON(C2H5)2 | 0.22 |

| 61 | H | NHCOCH3 | NA |

| 62 | H | NHCOC2H5 | NA |

| 63 | H | NHSO2CH3 | 0.394 |

| 64 | CON(C2H5)2 | H | NA |

| 65 | SO2N(C2H5)2 | H | NA |

All compounds were inactive at NPY Y1 receptor; the highest concentration tested in the assay was 10 μM, (NA = not active).

The carbamate analogues 51–65 were prepared by reacting the α,α-diphenylpiperidino-4-methanol with aryl chloroformates, obtained from the reaction of phenols with triphosgene, in the presence of iPr2EtN. The non-commercially available phenols were prepared by conversion of the appropriate aryl fluoride into the corresponding phenol with 2-butyn-1-ol and potassium tert-butoxide in DMSO (Scheme 5).23

Scheme 5.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 2-butyn-1-ol, KOtBu, DMSO, 125 °C microwave, 15 min.; (b) triphosgene, NaOH, CH2Cl2/H2O, 0 °C to rt, 3 h; (c) α,α-diphenylpiperidino-4-methanol, iPr2EtN, CH2Cl2, rt, 6 h.

In summary, we systematically explored the SAR of the hit molecule SF-11 that led to the identification of selective and highly potent small molecule NPY Y2 receptor antagonists 16 (CYM 9484; IC50=19 nM) and 54 (CYM 9552; IC50=12 nM). The investigation of in vivo PK and further lead optimization of the series of compounds will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grant 1U01AA018665.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Catapano LA, Manji HK. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:976. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammond MI. Drugs. 2001;4:920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaga T, Fujimiya M, Inui A. Peptides. 2001;22:501. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatemoto K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:5485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.18.5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sajdyk TJ. Drug Dev Res. 2005;65:301. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato N, Ogino Y, Mashiko S, Ando M. Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2009;19:1401. doi: 10.1517/13543770903251722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blomqvist AG, Herzog H. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:294. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michel MC, Beck-Sickinger A, Cox H, Doods HN, Herzog H, Larhammar D, Quirion R, Schwartz T, Westfall T. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker SL, Balasubramaniam A. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:420. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doods H, Gaida W, Wieland HA, Dollinger H, Schnorrenberg G, Esser F, Engel W, Eberlein W, Rudolf K. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;384:R3. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00650-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacchi F, Mathé AA, Jiménez P, Stasi L, Arban R, Gerrard P, Caberlotto L. Peptides. 2006;27:3202. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott CR, Small CJ, Kennedy AR, Neary NM, Sajedi A, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Brain Res. 2005;1043:139. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rimondini R, Thorsell A, Heilig M. Neurosci Lett. 2005;375:129. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andres CJ, Zimanyi IA, Deshpande MS, Iben LG, Grant-Young K, Mattson GK, Zhai W. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2883. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jablonowski JA, Chai W, Li X, Rudolph DA, Murray WV, Youngman MA, Dax SL, Nepomuceno D, Bonaventure P, Lovenberg TW, Carruthers NI. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1239. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lunniss GE, Barnes AA, Barton N, Biagetti M, Bianchi F, Blowers SM, Caberlotto L, Emmons A, Holmes IP, Montanari D, Norris R, Walters DJ, Watson SP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:4022. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunniss GE, Barnes AA, Barton N, Biagetti M, Bianchi F, Blowers SM, Caberlotto LL, Emmons A, Holmes IP, Montanari D, Norris R, Puckey GV, Walters DJ, Watson SP, Willis J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:7341. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanson DM, Wong VD, Jablonowski JA, Shah C, Rudolph DA, Dvorak CA, Seierstad M, Dvorak LK, Morton K, Nepomuceno D, Atack JR, Bonaventure P, Lovenberg TW, Carruthers NI. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5552. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brothers SP, Saldanha SA, Spicer TP, Cameron M, Mercer BA, Chase P, McDonald P, Wahlestedt C, Hodder PS. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:46. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S, Yi KY. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:1661. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spectral data for compound 16: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 7.64 – 7.62 (m, 2H), 7.57 – 7.54 (m, 6H), 7.29 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H), 7.15 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.75 – 4.66 (m, 2H), 3.12 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 2.99 – 2.89 (m, 1H), 2.59 (s, 6H), 1.59 – 1.46 (m, 2H), 1.40 – 1.31 (m, 2H). LC–MS (m/z): 510 [M+H]+. Compound 54: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.49 – 7.46 (m, 4H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H), 7.25 – 7.19 (m, 4H), 4.31 – 4.27 (m, 2H), 3.21 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 3.04 – 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.64 (t, J = 11.7 Hz, 1H), 1.66 – 1.61 (m, 2H), 1.43 – 1.39 (m, 2H), 1.12 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 6H). LC–MS (m/z): 523 [M+H]+.

- 22.Dollinger H, Esser F, Mihm G, Rudolf K, Schnorrenberg G, Gaida W, Doods HN. DE 19816929. [Chem. Abstr 1999, 131, 286 832]

- 23.Levin JI, Du MT. Synth Commun. 2002;32:1401. [Google Scholar]