Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Primary care providers need effective strategies for substance use screening and brief counseling of adolescents. We examined the effects of a new computer-facilitated screening and provider brief advice (cSBA) system.

METHODS:

We used a quasi-experimental, asynchronous study design in which each site served as its own control. From 2005 to 2008, 12- to 18-year-olds arriving for routine care at 9 medical offices in New England (n = 2096, 58% females) and 10 in Prague, Czech Republic (n = 589, 47% females) were recruited. Patients completed measurements only during the initial treatment-as-usual study phase. We then conducted 1-hour provider training, and initiated the cSBA phase. Before seeing the provider, all cSBA participants completed a computerized screen, and then viewed screening results, scientific information, and true-life stories illustrating substance use harms. Providers received screening results and “talking points” designed to prompt 2 to 3 minutes of brief advice. We examined alcohol and cannabis use, initiation, and cessation rates over the past 90 days at 3-month follow-up, and over the past 12 months at 12-month follow-up.

RESULTS:

Compared with treatment as usual, cSBA patients reported less alcohol use at follow-up in New England (3-month rates 15.5% vs 22.9%, adjusted relative risk ratio [aRRR] = 0.54, 95% confidence interval 0.38–0.77; 12-month rates 29.3% vs 37.5%, aRRR = 0.73, 0.57–0.92), and less cannabis use in Prague (3-month rates 5.5% vs 9.8%, aRRR = 0.37, 0.17–0.77; 12-month rates 17.0% vs 28.7%, aRRR = 0.47, 0.32–0.71).

CONCLUSIONS:

Computer-facilitated screening and provider brief advice appears promising for reducing substance use among adolescent primary care patients.

KEY WORDS: adolescents, substance use, primary care, screening, brief intervention, computer-assisted, alcohol, cannabis

What’s Known on This Subject:

Primary care settings provide an important venue for early detection of substance use and intervention, but adolescent screening rates need improvement. Screening and brief interventions appear effective in reducing adult problem drinking but evidence for effectiveness among adolescents is needed.

What This Study Adds:

A computer-facilitated system for screening, feedback, and provider brief advice for primary care can increase adolescent receipt of substance use screening across a variety of practice settings, and shows promise for reducing adolescents’ use of alcohol and cannabis.

More than 40% of US adolescents are current alcohol drinkers, and more than 20% use cannabis (marijuana) or another drug.1 This is a serious national problem because substance use is strongly linked to the leading causes of adolescent mortality and many other health problems.2–5 Primary care offices are promising venues for screening, prevention, and early intervention.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that health care providers screen all adolescents for substance use as part of routine preventive care.7,8 Adherence to this recommendation, however, is low.9,10 Stated reasons include lack of time and personnel to perform the screening, unfamiliarity with screening tools, lack of training in how to deal with positive screens, and lack of effective interventions.11

The CRAFFT is a valid and reliable screener for adolescent medical patients, and is brief enough to be practical for busy medical offices.12–14 “CRAFFT” is a mnemonic acronym formed by the first letters of key words in the test’s 6 yes/no questions (Fig 1). Each “yes” scores 1 point; a total score of ≥2 has a sensitivity of 0.80 and specificity of 0.86 for identifying substance abuse or dependence.13 Although the CRAFFT can be conducted by clinician-interview or self-administered questionnaire, adolescents report being more likely to provide honest answers on questionnaires, even when they know the provider will receive the results.15

FIGURE 1.

The CRAFFT screening interview.

To meet the needs of both providers and patients, we developed a computer-facilitated screening and brief advice (cSBA) system consisting of a computerized screening and educational component before the visit, and provider advice during the visit. There is substantial evidence from studies conducted in the United States,16–22 and other countries17,20,23,24 supporting the effectiveness of screening and brief physician advice among adult primary care patients, especially in the reduction of harmful drinking and its associated consequences (eg, motor vehicle crashes, emergency department visits).16–19 It is unknown, however, whether these findings are generalizable to younger patients, as there have been fewer studies among adolescents in primary care.25,26 Existing studies suggest that primary care screening and brief interventions can positively impact adolescent health issues, such as tobacco use,27–30 nutrition and physical activity,31,32 and depression.33,34 A large longitudinal study of 14-year-old primary care patients26 found that screening and brief provider counseling significantly increased helmet use but did not reduce adolescent alcohol or drug use, suggesting the need to explore supplemental strategies to enhance effectiveness, such as the computerized education component that occurs before the provider visit in the cSBA system.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the immediate and short- and long-term effects of the cSBA system for adolescents in primary care. Immediate effects included providers’ brief counseling behaviors during the visit and adolescents’ reactions to it. Short- and long-term effects were adolescents’ use of alcohol and cannabis 3- and 12-months after the visit. We hypothesized that, compared with treatment as usual (TAU), more cSBA patients would report receiving provider advice, rate the quality of the advice as high, and report less substance use at the 3-month follow-up; however, without reinforcement, we hypothesized that the effect would be reduced by the 12-month follow-up. A secondary objective was to assess the separate effects of the cSBA intervention on preventing initiation of substance use by nonusers, and on promoting cessation among users.

Methods

We conducted the study at 9 primary care offices in 3 New England states, and in 10 pediatric generalist offices in Prague, Czech Republic (for more detail, see Supplemental Information). We used a quasi-experimental before-after design to compare cSBA and TAU. We first held a 1-hour orientation at each site to explain the study’s purpose, procedures, and safety protocol, and instructed providers to continue their usual practices during the TAU phase. For the ensuing 18 months, we recruited and assessed the TAU group. At the crossover point, we conducted a 1-hour provider training and initiated the cSBA protocol at all sites, then recruited and tested the cSBA group during the final 18 months.

Recruitment procedures were identical at each site during both study phases. Patients aged 12 to 18 years arriving for routine care, who were medically and emotionally stable on the day of the visit, able to read and understand the cSBA program, and available for follow-ups, were eligible. Czech Republic adolescents are seen for well-visits biannually, so we primarily recruited 13-, 15-, and 17-year-old patients there. Adolescents who participated in the TAU phase were excluded from the cSBA phase. In both TAU and cSBA phases, research assistants (RAs) contacted families before the visit to explain the study purpose, procedures, and confidentiality protection, and instructed interested patients to arrive 30 minutes early for their appointment. Upon arrival, RAs privately obtained informed participant assent (<18 years) or consent (≥18 years). Parents gave informed consent either in person, by phone, or sent a signed consent form in with the patient (Czech Republic). Participants then completed the baseline assessment and, for those receiving the intervention, the cSBA program, before seeing the provider. Participants received a merchandise certificate for completing each assessment ($5 United States, 200 Kč [$10–$12] Czech Republic). The institutional review boards of Children’s Hospital Boston, all New England sites, and the Charles University Second Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (Prague, Czech Republic) approved the study protocol.

Intervention Protocol

The cSBA intervention began with a self-administered screening (Fig 1) that asks about lifetime and past-12-month use of substances followed by the CRAFFT questions. The CRAFFT screen had an embedded skip pattern, so that patients with no history of substance use completed the CAR question only. If the CRAFFT was completed, the program immediately displayed the individual’s CRAFFT score and risk-level (low, medium, high) on a thermometerlike graphic. All cSBA adolescents then viewed the same 10 pages of scientific information and true-life stories illustrating the health risks of substance use, which we created based on feedback from focus groups of adolescents who reported finding these types of information most compelling. All cSBA adolescents completed the same computer program before the medical visit, and the average completion time was 5 minutes. Providers received a report form with the screening results, risk level, and 6 to 10 “talking points” designed to prompt a 2- to 3-minute provider/teen conversation about the health effects of substance use, and that recommended abstinence. The talking points on health risks were the same regardless of patients’ substance use status but advice was individualized to either “not start” or “stop” using substances (see Supplemental Information). Provider training included a demonstration of the cSBA program, review of a sample provider report, and a 20-minute video demonstrating provider brief counseling. For the Czech Republic study, we translated, back-translated, culturally adapted, and validated the CRAFFT screen.35 We substituted 1 cSBA informational page on nonmedical use of prescription drugs with 1 on volatile inhalants, which is far more common there, and we translated/back-translated all other study materials.

Measures

The baseline assessment began with a past-90-day, modified timeline followback14,36 interview, separately recording frequency of use of each substance. Participants then self-administered a computerized questionnaire that assessed demographics and perceived substance use by peers, siblings, and parents (scales derived from the validated Personal Experience Inventory37,38). RAs recorded the office visit type and the provider’s gender and type. To evaluate potential historical confounding owing to the asynchronous study design, we asked respondents how often in the past 12 months they had heard information about alcohol or drugs in the news, in their school or community, or from friends or family.

Immediately after the visit, adolescents completed a post-visit checklist that assessed whether the provider gave advice not to use alcohol and drugs, their satisfaction with the visit, the likelihood of following their provider’s advice, and their rating of the way their provider gave the advice. At 3- and 12-month follow-up visits, participants completed assessments identical to the baseline either in person or by phone (>95%, because of the difficulty of scheduling in-person assessments). RAs ensured that participants could speak privately before conducting phone assessments. This difference in data collection mode occurred in both study arms equally and should not change any between-group effects.

Data Analyses

We conducted all analyses using SUDAAN v.10.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) with site as the nest variable to account for correlated error arising from our site cluster-sampling design. To assess immediate effects, we computed the proportions of patients who reported receiving provider advice not to use, receiving information regarding the health risks of substance use, being “very satisfied” with their visit, and being “very likely” to follow their provider’s advice generally, and, among those receiving advice about substance use, the percent rating the provider’s advice as “very good” or “excellent.”

The timeline followback–derived frequency-of-use variables were highly skewed, so we used a dichotomized use/no use as our primary short- and long-term outcome variable. Our a priori hypothesized outcome variables were rates of any use, initiation, and cessation. We defined initiation as any use at follow-up among those reporting no past-12-months use at baseline, and cessation as no use at follow-up among those reporting any past-12-months use at baseline. We compared any past-90-day use at the 3-month follow-up and any past-12-month use at the 12-month follow-up. We stratified analyses by country because of some different demographic variables, and by substance (alcohol, cannabis). We did not analyze use of drugs other than cannabis because of low prevalence (≤2%).

We used an “intent-to-treat” approach, analyzing cSBA adolescents regardless of whether they reported receiving provider advice. We excluded follow-up assessments completed >2 months late. We used χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables to assess baseline group equivalence. We dichotomized race (white non-Hispanic versus other [United States only]), parents in home (2 versus other), parent education level (≥college graduate versus other), and type of visit (well-visit versus other) to ensure adequate cell sizes. For analysis of the intervention effect on initiation and cessation by 3- and 12-month follow-up, we used logistic regression modeling with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to compute adjusted relative risk ratios (aRRR) for cSBA compared with TAU, controlling for demographics, peer/family substance use, visit/provider characteristics, and the multisite sampling design. These analyses inherently controlled for baseline use through stratification of participants into baseline nonuser and user groups. We ran separate models for 3- and 12-month outcomes because of the different timeframes examined (past 90 days versus past 12 months). To examine the intervention effect on use at follow-up, we used 2 types of analysis. We conducted logistic regression analysis (with GEE to account for within-site clustering) to compare use probabilities between groups at each follow-up, with baseline data for each outcome variable entered as a covariate in the model. This method of longitudinal data analysis corresponds to a Markov chain transition model where subsequent observations are conditional on previous observations.39 We also conducted a repeated measures analysis that included data from all 3 time points in mixed effects regression analyses, which modeled subject-specific coefficients as random effects and used a generalized linear model owing to the binary outcome (use or no use). The findings from the mixed effects modeling and GEE logistic regression analyses were no different, so we are presenting the latter results only.

We used all available data to examine potential nonresponse bias. We performed missing data imputation by using multivariable regression and receiver operating characteristic curves to determine the optimal probability cut point (see Supplemental Information for more detail). The imputed analyses results were similar to the nonimputed, so we are reporting results from nonimputed models.

Results

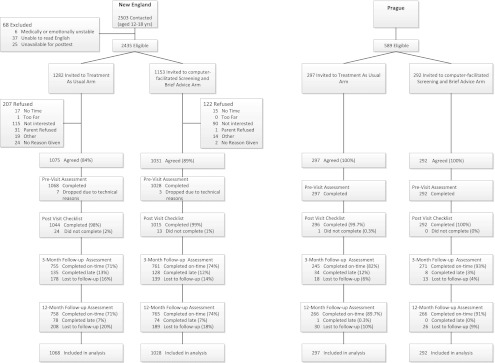

In New England, 2106 (86.5%) of 2435 eligible patients completed baseline assessments, with TAU participation rate slightly lower than cSBA (z-score = −4.01, P < .01) (Fig 2). TAU participants were older; more likely to be female; of “other” race; to have a parent who did not graduate college; and to report having a parent, sibling, or peer who uses substances (Table 1). They were less likely to be presenting for a well visit, and to have seen a nurse practitioner or a female provider. We controlled for these differences in all subsequent analyses. In Prague, 100% of eligible patients (589) participated, with no significant baseline between-group differences. There were no between-group differences in either country in the frequency of past-year exposure to substance-related messages outside the study. Follow-up rates were >70% in New England and >80% in Prague.

FIGURE 2.

Study design, recruitment, and retention in New England and in Prague, Czech Republic.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographics and Visit Characteristics

| New England | Prague, Czech Republic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL N (%) (N = 2096) | TAU n (%) (n = 1068) | cSBA n (%) (n = 1028) | ALL N (%) (N = 589) | TAU n (%) (n = 297) | cSBA n (%) (n = 292) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 15.8 ± 2.0 | 15.9 ± 2.0 | 15.6 ± 2.0 | 15.0 ± 1.6 | 15.0 ± 1.6 | 15.0 ± 1.6 |

| Females | 1220 (58.2) | 659 (61.7) | 561 (54.6) | 278 (47.2) | 139 (47.6) | 139 (46.8) |

| Race/Ethnicitya | ||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 1353 (64.6) | 689 (64.5) | 664 (64.6) | 589 (100) | 297 (100) | 292 (100) |

| Hispanic | 230 (11.0) | 106 (9.9) | 124 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian non-Hispanic | 151 (7.2) | 77 (7.2) | 74 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 217 (10.4) | 100 (9.4) | 117 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other non-Hispanic | 145 (6.9) | 96 (9.0) | 49 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Parents at home | ||||||

| Two parents | 1424 (69.2) | 703 (67.3) | 721 (71.0) | 379 (65.0) | 184 (63.2) | 195 (66.8) |

| One parent or other | 635 (30.8) | 341 (32.7) | 294 (29.0) | 204 (35.0) | 107 (36.8) | 97 (33.2) |

| Parents’ highest education level | ||||||

| College/University degree or higher | 973 (48.0) | 451 (44.1) | 522 (52.0) | 192 (33.1) | 92 (31.7) | 100 (34.5) |

| High school/Secondary schoolb graduate | 832 (41.0) | 427 (41.7) | 405 (40.3) | 217 (37.4) | 111 (38.3) | 106 (36.6) |

| Did not complete high school/secondary school | 81 (4.0) | 46 (4.5) | 33 (3.5) | 90 (15.5) | 44 (15.2) | 46 (15.9) |

| Don’t know | 141 (7.0) | 99 (9.7) | 42 (4.2) | 81 (140) | 43 (14.8) | 38 (13.1) |

| Visit type | ||||||

| Well visit | 1819 (87.9) | 851(81.0) | 968 (95.0) | 589 (100) | 297 (100) | 292 (100) |

| First visit | 220 (10.7) | 115 (11.0) | 105 (10.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Female provider | 1349 (64.9) | 663 (62.9) | 684 (67.1) | 522 (88.8) | 263 (88.9) | 259 (88.7) |

| Parent substance usec | 322 (15.4) | 170 (15.9) | 152 (14.8) | 64 (10.9) | 32 (11.0) | 32 (10.8) |

| Sibling substance usec | 392 (18.7) | 205 (19.2) | 187 (18.2) | 77 (13.2) | 41 (13.9) | 36 (12.5) |

| Peer substance usec | 1265 (60.5) | 658 (61.8) | 607 (59.1) | 396 (67.3) | 204 (68.9) | 192 (65.8) |

In the Czech Republic, 97% were Czech nationality and 3% other.

Includes secondary school or gymnasium for Czech sample.

Percentage reporting any “agree” response to scale items assessing youth-reported parent substance use, sibling substance use, and peer substance use.

Provider brief advice rates doubled in New England, and quadrupled in Prague (Table 2). More providers in both countries advised patients without substance use not to start, than advised patients with substance use to stop. Compared with TAU, more cSBA adolescents rated the provider advice as “Excellent” or “Very Good,” and being “very likely” to follow the provider’s advice and “very satisfied” with the visit.

TABLE 2.

Adolescents’ Reports of Provider’s Brief Counseling Behaviors and Ratings of Visit

| Provider Counseling Behaviors | New England | Prague, Czech Republic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | TAU n (%) (n = 1015) | cSBA n (%) (n = 1044) | aRRRa,b (95% CI) | n | TAU n (%) (n = 296) | cSBA n (%) (n = 292) | aRRRa,b (95% CI) | |

| Advised about alcohol | 2059 | 441 (42.2) | 707 (69.7) | 1.57 (1.44–1.71) | 586 | 70 (23.6) | 213 (73.2) | 3.10 (2.52–3.80) |

| Not to startc | 1280 | 278 (45.6) | 478 (71.3) | 1.53 (1.38–1.70) | 207 | 25 (25.8) | 78 (70.9) | 2.72 (1.90–3.90) |

| To stopd | 779 | 85 (19.6) | 153 (44.3) | 2.19 (1.70–2.84) | 379 | 19 (9.6) | 76 (42.0) | 4.36 (2.76–6.90) |

| Advised about cannabis and drugs | 2059 | 470 (45.0) | 720 (70.9) | 1.50 (1.38–1.63) | 588 | 72 (24.3) | 231 (79.1) | 3.27 (2.67–4.00) |

| Not to startc | 1609 | 366 (46.0) | 568 (69.9) | 1.47 (1.34–1.61) | 457 | 49 (21.0) | 167 (74.2) | 3.56 (2.75–4.59) |

| To stopd | 449 | 63 (25.5) | 109 (54.0) | 2.18 (1.60–2.97) | 129 | 16 (16.1) | 34 (50.7) | 3.17 (1.68–5.97) |

| Addressed health risks of alcohol | 2058 | 336 (32.2) | 673 (66.3) | 2.00 (1.80–2.23) | 588 | 36 (12.2) | 168 (57.5) | 4.79 (3.48–6.59) |

| Addressed health risks of cannabis and drugs | 2057 | 334 (32.1) | 657 (64.7) | 2.01 (1.81–2.24) | 588 | 37 (12.5) | 160 (54.8) | 4.49 (3.27–6.18) |

| “Excellent”/ “Very Good” rating of provider informatione | 1162 | 318 (70.5) | 545 (76.6) | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) | 300 | 27 (38.6) | 45 (63.0) | 1.67 (1.22–2.30) |

| “Very” likely to follow provider advice | 2057 | 554 (53.1) | 603 (59.5) | 1.13 (1.04–1.23) | 588 | 65 (22.0) | 94 (32.2) | 1.50 (1.31–1.98) |

| “Very” satisfied with visit | 2057 | 646 (61.9) | 679 (66.9) | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 588 | 115 (38.9) | 127 (43.5) | 1.12 (0.92–1.37) |

aRRR with TAU as the reference group.

US logistic regression models were run using SUDAAN v. 10.0 software to account for the multisite sampling design, and adjusted for age, gender, race, parent education level, provider type, provider gender, well visit, first visit, any lifetime smoking, any lifetime alcohol or drug use. Czech Republic models adjusted for age and gender only as there were no other differences between experimental groups.

Rates of advice to not start alcohol or cannabis/drug use were calculated only for adolescents who had no prior use of the substance.

Rates of advice to stop were calculated only for adolescents who had ever used the substance.

Among adolescents reporting receiving advice about alcohol or drugs.

New England cSBA adolescents reported lower rates of any substance use compared with TAU at both follow-ups (3-months: aRRR=0.62 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.44–0.87], adjusted absolute risk difference [ARD] = 9.3%, number needed to treat [NNT] = 11; 12-month aRRR = 0.80 (0.64–0.99), ARD = 7.9%, NNT = 13), largely owing to lower drinking rates at both follow-ups. Among drinkers, there was significantly more cessation of drinking at 3 months, but the effect dissipated by 12 months (Table 3). In contrast, the effect on initiation was not significant at 3 months, perhaps because of small numbers, but robust and significant at 12 months: 44% fewer cSBA adolescents than TAU started drinking during the 12-month study period (ARD = 6%, NNT = 17). We found promising effect sizes in the hypothesized direction for any use and initiation of cannabis at 3 months, but they did not reach statistical significance and dissipated by 12 months.

TABLE 3.

Rates of Self-Reported Alcohol and Cannabis Use, Initiation, and Cessation at Baseline and 3- and 12-mo Follow-up Visits

| Any Past-90-Day Use at 3-Month Follow-up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New England | Prague, Czech Republic | |||||||

| N | TAU n (%) (n = 755) | cSBA n (%) (n = 761) | aRRRa,c (95% CI) | N | TAU n (%) (n = 245) | cSBA n (%) (n = 271) | aRRRa,c (95% CI) | |

| Alcohol | ||||||||

| Baseline | 1516 | 155 (20.5) | 122 (16.0) | 0.77 (0.56–1.05) | 516 | 113 (46.1) | 129 (47.6) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) |

| 3 Months | 1515d | 173 (22.9) | 118 (15.5) | 0.54 (0.38–0.77)e | 516 | 127 (51.8) | 126 (46.5) | 0.82 (0.63–1.06) |

| Initiationb | 1066 | 30 (5.9) | 17 (3.1) | 0.64 (0.32–1.28) | 198 | 10 (11.4) | 13 (11.8) | 0.96 (0.42–2.21) |

| Cessationb | 450 | 101 (41.4) | 104 (50.7) | 1.49 (1.17–1.91)e | 318 | 40 (25.5) | 48 (29.8) | 1.54 (0.99–2.38) |

| Cannabisa | ||||||||

| Baseline | 1516 | 62 (8.2) | 62 (8.1) | 1.25 (0.79–1.95) | 516 | 16 (6.5) | 14 (5.2) | 0.74 (0.35–1.54) |

| 3 Months | 1515d | 72 (9.5) | 56 (7.4) | 0.68 (0.40–1.15) | 516 | 24 (9.8) | 15 (5.5) | 0.37 (0.17–0.77)e |

| Initiationb | 1309 | 15 (2.3) | 8 (1.2) | 0.45 (0.18–1.11) | 442 | 8 (3.8) | 2 (0.9) | 0.22 (0.05–1.04) |

| Cessationb | 206 | 50 (46.7) | 51 (51.5) | 1.00 (0.72–1.40) | 74 | 16 (50.0) | 29 (69.0) | 1.50 (0.97–2.32) |

| Any Past-12-Month Use at 12-Month Follow-up | ||||||||

| New England | Prague, Czech Republic | |||||||

| N | TAU n (%) (n = 758) | cSBA n (%) (n = 765) | aRRRa,c (95% CI) | N | TAU n (%) (n = 266) | cSBA n (%) (n = 264) | aRRRa,c (95% CI) | |

| Alcohol | ||||||||

| Baseline | 1523 | 240 (31.7) | 194 (25.4) | 0.82 (0.64–1.06) | 530 | 163 (61.3) | 153 (58.0) | 0.89 (0.76–1.03) |

| 12 Months | 1523 | 284 (37.5) | 224 (29.3) | 0.73 (0.57–0.92)e | 530 | 199 (74.8) | 185 (70.1) | 0.96 (0.86–1.04) |

| Initiationb | 1089 | 92 (17.8) | 68 (11.9) | 0.66 (0.47–0.93)e | 216 | 35 (43.7) | 37 (33.3) | 0.76 (0.53–1.08) |

| Cessationb | 434 | 48 (20.0) | 38 (19.6) | 1.50 (0.93–2.42) | 316 | 9 (5.5) | 5 (3.3) | 1.18 (0.37–3.73) |

| Cannabis | ||||||||

| Baseline | 1522f | 101 (13.3) | 95 (12.4) | 0.77 (0.56–1.05) | 529f | 36 (13.6) | 38 (14.4) | 1.02 (0.63–1.64) |

| 12 Months | 1522f | 133 (17.5) | 119 (15.6) | 0.85 (0.61–1.19) | 529f | 76 (28.7) | 45 (17.0) | 0.47 (0.32–0.71)e |

| Initiationb | 1326 | 58 (8.8) | 52 (7.8) | 0.81 (0.54–1.21) | 458 | 47 (20.5) | 22 (9.7) | 0.47 (0.29–0.76)e |

| Cessationb | 196 | 27 (26.7) | 28 (29.5) | 1.01 (0.57–1.78) | 74 | 7 (19.4) | 15 (39.5) | 2.53 (1.06–6.05)e |

New England logistic models for both 3- and 12-month outcomes adjusted for the multisite sampling design; baseline past-12-month substance use; age; gender; parent education level; type of visit (well visit or other); perceived parent, sibling, and peer substance use; provider gender; and connectedness to provider. Prague models adjusted for the multisite sampling design, baseline past-12-month substance use, age, and gender.

“Initiation” models analyzed only participants reporting no past-12-month use at baseline, whereas “cessation” models included only those reporting any past-12-month use at baseline. New England and Prague models adjusted for the same variables listed in footnote a, excluding baseline substance use, which is already accounted for by the stratified analyses.

aRRRs with TAU as the reference group.

There were missing data for 1 respondent each in 3-month New England alcohol use (cSBA) and cannabis use (TAU).

P < .05.

There were missing data for 1 respondent each in 12-month marijuana use for New England and Prague TAU groups.

There was no significant cSBA effect on any substance use or on alcohol use in Prague; however, there were significantly reduced cannabis use rates compared with TAU at both follow-ups (3-month ARD = 6%, NNT = 16; 12-month ARD = 15%, NNT = 7). At the 12-month follow-up, we found significant effects for cSBA on both initiation and cessation of cannabis. Compared with New England, Prague participants reported significantly higher drinking rates over lifetime (aRRR = 2.72, 95% CI 2.44–3.04), past-12-months (aRRR = 3.36, 95% CI 2.95–3.82), and past-90-days (aRRR = 4.84, 4.00-5.87). Cannabis use rates were similar between countries.

Discussion

This study provides preliminary evidence of the efficacy of a structured cSBA system in both increasing primary care provider counseling regarding substance use, and reducing adolescent substance use. The cSBA system doubled the number of adolescents receiving brief counseling and increased patient satisfaction with the provider and the visit; however, providers still reached only ∼70% in the cSBA group. We are unable to say why this number was not higher, nor why more providers gave advice not to start than to stop. The latter may be because of some providers’ desire to avoid confrontation with patients who are using substances.

We also found that, with only 2 to 3 minutes of provider time, the cSBA system reduced, relative to usual care, adolescent alcohol use in New England and cannabis use in Prague, with effects persisting through the 12-month study period. The natural trend for substance use prevalence, as shown in national surveys and seen in the current study, is to increase as adolescents age41; however, the cSBA group had significantly lower rates of use compared with TAU at each follow-up, resulting in a slower increase over time.

The effects on cannabis use in New England were smaller in apparent size, and all in the hypothesized direction, but they did not reach statistical significance. Cannabis use was far less prevalent than drinking in our sample, resulting in small numbers and lower power. Our sample size may have been inadequate to detect an intervention effect above that of assessment reactivity, which can have a substantial impact on substance use.40–42

In Prague, alcohol use was not affected. We suspect cultural factors played a substantial role. Alcohol use is highly normative in the Czech Republic, which has one of the highest per capita rates of beer consumption among all countries.43 Czech beer is inexpensive (between $1 and $2 US43), and the drinking age is lower than in the United States (18 years). In contrast, cannabis use is not a cultural norm. Our collaboration with the Czech Republic began with an e-mail from a Prague psychiatrist requesting permission to translate and use the CRAFFT screen in a Ministry of Health project to address a sharp rise in adolescent drug use after the 1989 “Velvet Revolution.”44 It is therefore gratifying to see that the Czech cSBA system had a powerful and lasting effect on cannabis use. The reasons for different findings in the United States and Czech Republic need further exploration, but underscore the value of multicultural studies.

To date, most studies evaluating screening and brief interventions with adolescents have been conducted in emergency departments,45–48 college campuses,21,49–53 or schools.54–57 The primary care office is a key setting for adolescent screening and brief intervention, with more than 22 million preventive care medical office visits by patients aged 15 to 24 each year,58 compared with 19 million emergency department visits.59 Also, primary care providers often have long-term relationships with patients and their families, potentially making brief advice more powerful. The use of computers to facilitate the process resulted in increased frequency and quality of physician brief advice, with minimal time burden on providers.

We could find no other published studies on primary care screening and brief intervention for adolescent substance use in English-language journals. We found 1 small study (n = 99) conducted in a single site by De Micheli and colleagues in Brazil.60 At 6-month follow-up, they found significantly lower rates of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among youth receiving a prevention intervention. Our study expands this previous work to a larger sample, a variety of practice types, and 2 other countries, enhancing generalizability of the findings and supporting the feasibility of implementation across a range of settings. An additional strength of the current study is that we compared our intervention to TAU that often already included substance use screening and ad hoc advice. This conservative approach may have made it more difficult to detect an intervention effect, but it increased the likelihood that a detected effect is robust.

Our study had potential limitations. We used a nonrandomized, asynchronous study design in which historical trends or other unmeasured group differences may have confounded our results. The 2 groups in New England were not equivalent in baseline substance use, although we controlled for this in data analysis. All study sites were in New England and Prague. Other locations could be different. Our study relied on self-reported and interviewer-collected data, which may be prone to recall error and social desirability bias. Previous studies have shown self-report to be a valid method for measuring substance use among adolescents, however, and it compares favorably with other methods of substance use detection, such as laboratory testing.14,61,62 Although there was 25% to 30% loss to follow-up in our New England sample, attrition was similar between groups, both in the rates and the profile of those lost to follow-up, and we found that our results did not change after missing data imputation. Finally, we were unable to assess effects on use of drugs other than cannabis because of insufficient numbers.

Future studies should use larger samples and randomized designs, include more information on the negative health effects of substance use, and add new strategies designed to extend the intervention’s effect over time. They should also include strategies to improve intervention fidelity among providers, such as self-report adherence checklists and audiotaping of brief advice with review and feedback. Finally, studies are needed to determine the cost-effectiveness/cost-benefit of cSBA, as well as to elucidate its mechanisms of action so as to promote its effective implementation and dissemination.

Conclusions

Computer-facilitated screening and provider brief advice appears to be a promising strategy for reducing substance use among adolescent primary care patients, although replications of this study are needed with larger samples. The protocol involved only 1 hour of provider training, 5 minutes of patient time before the visit, and 2 to 3 minutes of provider time during the encounter, with some positive effects sustained up to a year later. Providers today face opposing pressures: recommendations to screen patients for more and more problems, and financial realities that require they see more patients quickly.14,63,64 Use of a computer-facilitated system such as this one may offer a way to improve both patient care and provider efficiency.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the physicians and staff of The New England Partnership for Substance Abuse Research for assistance with study implementation, including Judy Shaw, RN, MPH, Executive Director, Vermont Child Health Improvement Program; Colleen Sheppard, RN, BSN and Julia Lee, PNP, Division of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Tufts Medical Center; Judy Casarella, PNP, and Elizabeth Blair, NP, Cambridge Health Alliance; Holly Vanwinkle, Milton Family Practice Clinical Practice Supervisor; and Donna Kaynor, Colchster Clinical Practice Supervisor. For their invaluable assistance in the Czech Republic, the authors thank Eva Cápová, the Executive Director of the Center for Evaluation, Prevention, and Research on Substance Abuse, and all of the participating physicians: MUDr Karel Holub, MUDr Alena Mottlová, MUDr Marie Schwarzová, MUDr Jitka Bĕlorová, MUDr Leona Tylingerová, MUDr Petra Vlková, MUDr Jaroslava Chaloupková, MUDr Jedličková Vĕra, and MUDr Marie Kolářová, and MUDr Renata Ruzková. The authors acknowledge research assistants Nohelani Lawrence, Joy Gabrielli, Ariel Berk, Melissa Rappo, Jessica Hunt, Stephanie Jackson, Amy Danielson, Jessica Randi, Michael Krauthamer, and Soumya Ashok for their help in data collection; and Janine Bacic, MS, and Emily Blood, PhD, for their biostatistical assistance. The authors thank the adolescent patients who agreed to participate and their parents who gave permission.

Glossary

- ARD

absolute risk difference

- aRRR

adjusted relative risk ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- CRAFFT

mnemonic acronym formed by the first letters of key words in the test’s 6 yes/no questions

- cSBA

computer-facilitated screening and brief advice

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- NNT

number needed to treat

- RA

research assistant

- TAU

treatment as usual

Footnotes

Drs Harris and Knight had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; Drs Harris (study co-principal investigator), Csémy (Czech Republic principal investigator), Van Hook (study manager), Boulter (site principal investigator), Brooks (site principal investigator), Carey (site principal investigator), Kossack (site principal investigator), Kulig (site principal investigator), Van Vranken (site principal investigator), and Knight (study principal investigator) and Mr Sherritt (study data manager) and Ms Starostova (Czech Republic data manager) were responsible for study conception/design; Drs Harris, Van Hook, and Knight and Mr Sherritt obtained funding; Drs Harris, Csemy, Van Hook, Boulter, Brooks, Carey, Kossack, Kulig, Van Vranken, and Knight and Mr Sherritt, Ms Starostova, and Ms Johnson were responsible for acquisition of data; Drs Harris, Csemy, Van Hook, and Knight and Mr Sherritt, Ms Starostova, and Ms Johnson were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data; Drs Harris, Csemy, Van Hook, and Knight and Mr Sherritt, Ms Starostova, and Ms Johnson were responsible for manuscript preparation; Drs Harris, Csemy, Van Hook, Boulter, Brooks, Carey, Kossack, Kulig, Van Vranken, and Knight and Mr Sherritt, Ms Starostova, and Ms Johnson were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Drs Harris, Csemy, Van Hook, Boulter, Brooks, Carey, Kossack, Kulig, Van Vranken, and Knight and Mr Sherritt, Ms Starostova, and Ms Johnson provided study supervision; Mr Sherritt, Ms Johnson, and Drs Van Hook, Boulter, Brooks, Carey, Kossack, Kulig, and Van Vranken provided administrative, technical, or material support; and Drs Harris, Csemy, Van Hook, Boulter, Brooks, Carey, Kossack, Kulig, Van Vranken, and Knight and Mr Sherritt, Ms Starostova, and Ms Johnson were responsible for final approval of the version to be published.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00227877).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This study was supported by grant R01DA018848 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and included a competing supplement for international research on drug addiction (R01DA018848-03S1). Other support was provided by grant K07 AA013280 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Dr Knight, and grant T20MC07462 to Drs Knight and Van Hook and grant T71NC0009 to Dr Harris from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, the Davis Family Charitable Foundation, the Carl Novotny & Judith Swahnberg Fund, the Ryan Whitney Memorial Fund, and the J.F Maddox Foundation. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(5):1–142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau Child Health USA 2010. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adrian M, Barry SJ. Physical and mental health problems associated with the use of alcohol and drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38(11-13):1575–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang G, Sherritt L, Knight JR. Adolescent cigarette smoking and mental health symptoms. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36(6):517–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DuRant RH, Smith JA, Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP. The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):286–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulig JW, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: the role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):816–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elster A, Kuznets N, eds. AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagan J, Shaw J, Duncan P, eds. Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics Periodic Survey of Fellows #31: Practices and Attitudes Toward Adolescent Drug Screening. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, Division of Child Health Research; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellen JM, Franzgrote M, Irwin CE, Jr, Millstein SG. Primary care physicians’ screening of adolescent patients: a survey of California physicians. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22(6):433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Hook S, Harris SK, Brooks TL, et al. New England Partnership for Substance Abuse Research The “Six T’s”: barriers to screening teens for substance abuse in primary care. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):456–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(6):607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy S, Sherritt L, Harris SK, et al. Test-retest reliability of adolescents’ self-report of substance use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(8):1236–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight JR, Harris SK, Sherritt L, et al. Adolescents’ preference for substance abuse screening in primary care practice. Subst Abus. 2007;28(4):107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers. A randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1039–1045 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossberg PM, Brown DD, Fleming MF. Brief physician advice for high-risk drinking among young adults. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):474–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL. Brief physician advice for problem drinkers: long-term efficacy and benefit-cost analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(1):36–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization Brief Intervention Study Group A cross-national trial of brief interventions with heavy drinkers. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:948–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Grossberg PM, et al. Brief physician advice for heavy drinking college students: a randomized controlled trial in college health clinics. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(1):23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace P, Cutler S, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of general practitioner intervention in patients with excessive alcohol consumption. BMJ. 1988;297(6649):663–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18(2):CD004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erickson SJ, Gerstle M, Feldstein SW. Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health care settings: a review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1173–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozer EM, Adams SH, Orrell-Valente JK, et al. Does delivering preventive services in primary care reduce adolescent risky behavior? J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(5):476–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pbert L, Fletcher KE, Flint AJ, Young MH, Druker S, DiFranza J. Smoking prevention and cessation intervention delivery by pediatric providers, as assessed with patient exit interviews. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/3/e810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pbert L, Flint AJ, Fletcher KE, Young MH, Druker S, DiFranza JR. Effect of a pediatric practice-based smoking prevention and cessation intervention for adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/121/4/e738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hum AM, Robinson LA, Jackson AA, Ali KS. Physician communication regarding smoking and adolescent tobacco use. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/127/6/e1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollis JF, Polen MR, Whitlock EP, et al. Teen reach: outcomes from a randomized, controlled trial of a tobacco reduction program for teens seen in primary medical care. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):981–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg-Smith SM, Stevens VJ, Brown KM, et al. The Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC) Research Group A brief motivational intervention to improve dietary adherence in adolescents. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(3):399–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Lee PW, Starr P. Changing adolescent health behaviors: the healthy teens counseling approach. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(suppl 5):S359–S364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoek W, Marko M, Fogel J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of primary care physician motivational interviewing versus brief advice to engage adolescents with an Internet-based depression prevention intervention: 6-month outcomes and predictors of improvement. Transl Res. 2011;158(6):315–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Reinecke MA, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an Internet-based depression prevention program for adolescents (Project CATCH-IT) in primary care: 12-week outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(1):23–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Csemy L, Knight JR, Starostova O, Sherritt L, Kabicek P, Van Hook S. Adolescents substance abuse screening program: experience with Czech adaptation of the CRAFFT screening test. Vox Pediatriae. 2008;8(6):35–36 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobell L, Sobell M. Alcohol Timeline Followback User's Manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winters K, Stinchfield R, Henly G. The Personal Experience Inventory test and manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henly GA, Winters KC. Development of psychosocial scales for the assessment of adolescents involved with alcohol and drugs. Int J Addict. 1989;24(10):973–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeger SL, Liang K-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein EE, Drapkin ML, Yusko DA, Cook SM, McCrady BS, Jensen NK. Is alcohol assessment therapeutic? Pretreatment change in drinking among alcohol-dependent women. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(3):369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kypri K. Methodological issues in alcohol screening and brief intervention research. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kypri K, Langley JD, Saunders JB, Cashell-Smith ML. Assessment may conceal therapeutic benefit: findings from a randomized controlled trial for hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(1):62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Euromonitor International. Who Drinks What? Identifying International Drinks Consumption Trends. 2nd edition London: Euromonitor International Ltd; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Csémy L, Kubicka L, Nociar A. Drug scene in the Czech Republic and Slovakia during the period of transformation. Eur Addict Res. 2002;8(4):159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):989–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monti PM, Colby SM, O'Leary TA. Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens through Brief Interventions. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tait RJ, Hulse GK, Robertson SI, Sprivulis PC. Emergency department-based intervention with adolescent substance users: 12-month outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(3):359–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kypri K, Langley JD, Saunders JB, Cashell-Smith ML, Herbison P. Randomized controlled trial of web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):530–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kypri K, Saunders JB, Williams SM, et al. Web-based screening and brief intervention for hazardous drinking: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2004;99(11):1410–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, Mullett N, O’Brien MC. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in a college student health center: a randomized controlled trial. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009;(16):131–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kypri K, Hallett J, Howat P, et al. Randomized controlled trial of proactive web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention for university students. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(16):1508–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Werch CE, Bian H, Moore MJ, Ames S, DiClemente CC, Weiler RM. Brief multiple behavior interventions in a college student health care clinic. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(6):577–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Werch CE, Carlson JM, Pappas DM, Edgemon P, DiClemente CC. Effects of a brief alcohol preventive intervention for youth attending school sports physical examinations. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(3):421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grenard JL, Ames SL, Wiers RW, Thush C, Stacy AW, Sussman S. Brief intervention for substance use among at-risk adolescents: a pilot study. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(2):188–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Werch CE, Bian H, Carlson JM, et al. Brief integrative multiple behavior intervention effects and mediators for adolescents. J Behav Med. 2011;34(1):3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Werch CE, Bian H, Moore MJ, et al. Brief multiple behavior health interventions for older adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(2):92–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cherry DK, Hing E, Woodwell DA, Rechsteiner MS. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2008

- 59.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 Emergency Department Summary. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Micheli D, Fisberg M, Formigoni ML. Study on the effectiveness of brief intervention for alcohol and other drug use directed to adolescents in a primary health care unit [in Portuguese]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2004;50(3):305–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Babor TF, Kranzler HR, Lauerman RJ. Early detection of harmful alcohol consumption: comparison of clinical, laboratory, and self-report screening procedures. Addict Behav. 1989;14(2):139–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Henly GA, Schwartz RH. Validity of adolescent self-report of alcohol and other drug involvement. Int J Addict. 1990-1991;25(11A):1379–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Belamarich PF, Gandica R, Stein RE, Racine AD. Drowning in a sea of advice: pediatricians and American Academy of Pediatrics policy statements. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/4/e964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomas JW, Grazier KL, Ward K. Economic profiling of primary care physicians: consistency among risk-adjusted measures. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 pt 1):985–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.