Abstract

Foster youth are at risk of poor adult outcomes. Research on the role of mentoring relationships for this population suggests the value of strategies that increase their access to adult sources of support, both while in foster care and as they reach adulthood. We conducted semi-structured, individual qualitative interviews with 23 former foster youth ages 18-25 regarding their relationships with supportive non-parental adults. We sought to identify factors that influence the formation, quality, and duration of these relationships and to develop testable hypotheses for intervention strategies. Findings suggest several themes related to relationship formation with non-parental adults, including barriers (e.g., youth's fears of being hurt) and facilitators (e.g., patience from the adult). Distinct themes were also identified relating to the ongoing development and longevity of these relationships. Youth also described multiple types of support and positive contributions to their development. Proposed intervention strategies include systematic incorporation of important non-parental adults into transition planning, enhanced training and matching procedures within formal mentoring programs, assistance for youth to strengthen their interpersonal awareness and skills, and the targeting of specific periods of need when linking youth to sources of adult support. Recommended research includes the development, pilot-testing, and evaluation of proposed strategies.

1. Introduction

Youth in foster care are at high risk of having poor adult outcomes in terms of educational attainment, employment, homelessness, mental and physical health, and delinquent and risky health behavior compared with their general population peers (Ahrens, DuBois, Richardson, Fan, & Lozano, 2008; Barth, 1990; Blome, 1997; Cheung & Heath, 1994; Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; Courtney, Terao, and Bost, 2004; Courtney, Dworsky, Ruth, Havlicek, Perez, and Keller, 2007; Pecora et al., 2006). Recent federal legislation has emphasized the importance of providing effective services to assist foster care youth in their transition to adulthood (H.R. 3443, 106th Cong., The Foster Care Independence Act of 1999; H.R. 6893--110th Cong., Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008) and an emphasis is being placed on the evaluation of strategies for this purpose (Montgomery, Donkoh, & Underhill, 2006 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, July 2008a; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, July 2008b).

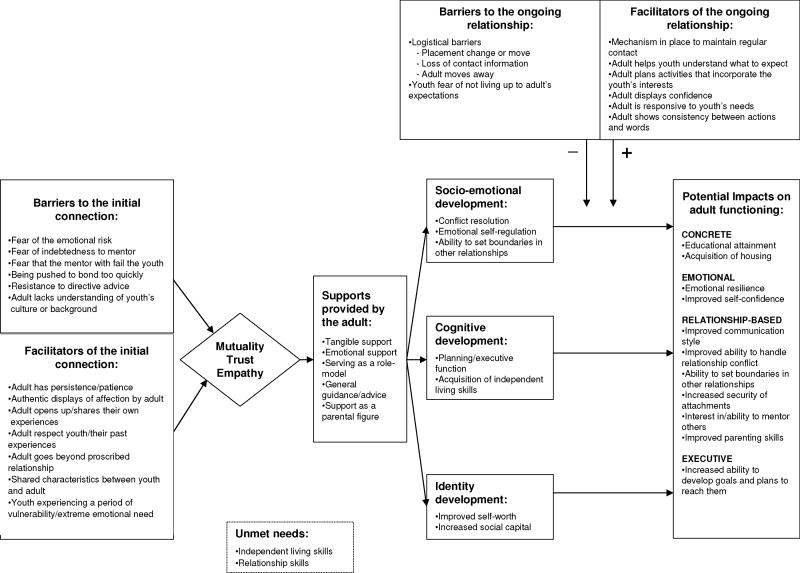

Mentoring programs are increasingly being employed in the practice community with the goal of improving outcomes for youth in foster care (Daining & DePanfilis, 2007; H.R. 3443, 106th Cong; Mech, Pryde, & Rycraft, 1995). Among studies of general population youth, programs that seek to establish mentoring relationships between participating youth and non-parental adult volunteers have been shown to be both effective (DuBois, Holloway, Valentine, & Cooper, 2002; DuBois & Silverthorn, 2005) and potentially cost-effective (Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2004) in promoting positive youth outcomes. Jean Rhodes (2005), in her model of how mentoring relationships support these positive outcomes, theorizes that when a bond is formed between a mentor and mentee that involves trust, empathy and mutual benefit, the relationship can produce improvements in the youth's socio-emotional, cognitive, and identity development (see Figure 1). Gains in socio-emotional development, in turn, are posited to yield improvements in relationships with parents and peers (Rhodes, 2002, 2005; Rhodes, Spencer, Keller, Liang, & Noam, 2006). Collectively, these processes are hypothesized to improve youth psychological, behavioral, and educational outcomes. Specific types of support that may mediate such improvements include provisions of guidance and advice, emotional support, role-modeling, and tangible/instrumental assistance (America's Promise Alliance, 2006; McDonald, Erickson, Johnson, & Elder, 2007; Spencer, 2006). Rhodes and colleagues also have proposed that the effects of mentoring relationships may be moderated by several factors. These include the length and quality of the relationship, the mentor's background (i.e., whether or not they are in a helping profession), and the youths' past relationships with parents and other caregivers, their competency in social situations, their developmental stage, and their current family and community context (Rhodes, 2002, 2005; Rhodes et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Initial Conceptual Model of the Impacts of Mentoring Relationships of Youth (Rhodes, 2002 & 2005).

Evidence has been obtained in support of the above model (for a review, see Rhodes, 2005). However, available research also suggests that mentoring relationships developed in the context of formal programs may function differently from those that are more naturally-occurring, and may have varying degrees of benefit across different populations of youth (DuBois et al., 2002). Youth who are involved with the foster system may be one population that experiences less consistent benefits from formal mentoring programs when compared with other populations of youth (Spencer, Collins, Ward, & Smashnaya, 2010). In a nested study which utilized data from a larger randomized controlled trial comparing youth involved with the Big-Brothers, Big Sisters program and waitlist controls, Rhodes, Haight, and Briggs (1999) found that for youth in the foster system, formal mentoring relationships were associated with improvements in youth-report of both pro-social and self-esteem enhancing support from peers over 18 months; in contrast decrements on these measures occurred over time for non-mentored youth in the foster system. The foster parents of mentored youth also reported greater improvements in the youth's social skills and comfort/trust interacting with others compared with the parents of non-foster youth with mentors (Rhodes et al., 1999). However, in another study involving youth in state custody (Britner & Kraimer-Rickaby, 2005), no difference was found between programmatically mentored youth with intact matches and non-mentored youth at 6-18 months after the program youth had been paired with mentors. Youth who were in matches that had terminated early (i.e., that had ended within the first 6 months) also had increases in delinquent behavior in comparison to youth in the intact match and non-mentored groups. Similarly, in a study of general population youth from the same larger study sample used by Rhodes and colleagues (1999), Grossman and Rhodes (2002) found that the youth having a history of abuse or neglect was a risk factor for early termination of the mentoring relationship. This investigation also found that at 1 year, youth whose matches had terminated within the first 3 months had decrements in self-reported educational, psychosocial, and risk-behavior outcomes compared to control youth.

Together, available findings suggest that youth in foster care may be more prone to disruption of programmatically-established mentoring relationships, as well as to the harmful effects of such disruptions. This may be due in part to the prior exposure of these youth to maltreatment and/or disruptions in their relationships with caregivers, experiences that have been associated with increased rates of maladaptive relationship styles later in life (Alexander, 1993; Gauthier, Stollak, Messé, & Aronoff, 1996; Katsikas, 1996; Trapp; 1996; Weinfield, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2000). This possibility underscores the importance of better understanding the factors that promote maintenance of mentoring relationships over time for youth in foster care. In a recent qualitative study of 20 adults and 11 adolescent male and female youth in the general population who had been in a programmatic match that had ended early, several deficiencies in mentor relational skills were cited by youth as reasons for terminated matches (Spencer, 2007). These include a lack of youth driven interactions, unrealistic expectations of the youth by the mentor, unfulfilled expectations for the relationship by the youth or the mentor, and an inability to bridge cultural differences. No studies to our knowledge have specifically focused on the reasons for termination of matches among formal mentoring relationships of youth in foster care. It seems likely, however, that the above factors not only apply, but may be more pronounced in this vulnerable population.

Mentoring relationships that emerge more naturally from youths' existing social networks may be less susceptible to the limitations of programmatic mentoring relationships noted above. This may be especially true for youth in foster care given their potential to experience greater difficulty forming trusting relationships with others, including unknown adults from mentoring programs. Consistent with this hypothesis, several recent studies of youth in the foster system and their relationships with important non-parental adults or “natural mentors” have indicated a broader and seemingly more consistent array of positive outcomes associated with these ties relative to those evident for mentoring ties established through formal programs. In these studies, youth reports of having a natural mentor have been associated with better physical health, less stress and depression, better odds of employment, increased educational attainment, and reduced risk of suicidality, having a sexually transmitted infection, hurting someone in a fight, being arrested, and being homeless (Ahrens et al., 2008; Collins, Spencer, & Ward, 2010; Courtney & Lyons, 2009; Munson & McMillen, 2009).

Just as foster youth may respond differently to participation in formal mentoring programs, there are also some data to suggest that there may be differences in the characteristics and scope of the relationships that these youth have with non-parental adult mentors created outside of a program in comparison to those experienced by other populations of youth. For example, in research examining the potential impacts of non-parental mentors among populations of at-risk youth using a nationally-representative database, youth in foster care were more likely than youth with learning disabilities to report receiving tangible or instrumental support (e.g., financial assistance or help getting a ride to work) from their mentors and to indicate that their mentors had served as substitute parental figures (Ahrens et al., 2008; Ahrens, DuBois, Lozano, Fan, & Richardson, 2010). In addition, relationships with mentors were associated with improvements in a larger number of adult outcomes for youth in the foster system compared to youth with learning disabilities. Farruggia, Greenberger, Chen, and Heckhausen (2006) similarly concluded in a separate study that relationships with “very important” non-parental adults may play a unique role in offsetting poor relationships with biological parents for this population. Taken together, these preliminary data suggest that foster youth may receive more extensive and/or different types of support in mentoring relationships than other populations of youth, which may also result in a wider range of impacts for this population as well.

Given the potential benefits of relationships with non-parental adults for youth in foster care, several recent studies have used both qualitative (Collins et al., 2010; Munson, Smalling, Spencer, Scott, & Tracy, 2010) and quantitative (Greeson, Usher, & Grinstein-Weiss, 2010) methods to explore the these relationships in more detail, in order to understand the types of adults with whom youth tend to form relationships as well as how these relationships function and what characteristics of the relationships are most important in supporting positive outcomes for these youth. The basic exploration of such moderators and mediators of mentoring relationships and positive outcomes for individual populations of youth has been recently identified as an important but understudied area of research (DuBois, Doolittle, Yates, Silverthorn, & Tebes, 2006). The findings of these investigations suggest that a number of differing types of adults serve as important non-parental sources of support for youth in foster care, including those adults who become formally involved with youth through the foster system (Collins et al., 2010; Munson et al., 2010) and that such relationships can offer a wide range of supports consistent with those that have been previously described including the provision of guidance and advice, emotional support, tangible/instrumental support, and serving as a substitute parental figure (Greeson et al., 2010; Munson et al., 2010). Greeson et al. (2010) specifically found that youth who reported receiving guidance and advice, role modeling, and “parent like” support from their mentors had increased economic assets compared with those who did not report that their mentor had provided these supports. Munson et al. (2010) also found that youth in foster care valued several specific relationship characteristics, including feeling that the adult was consistent, trustworthy, authentic, respectful, and empathic and having known the adult for a long time.

In the present study, we sought to use one-on-one qualitative interviewing techniques to extend understanding of how relationships with important non-parental adults function for young adults who have been in foster care. In doing so, we sought to capture a broader range of relationships that have been explored in previous studies on naturally-occurring relationships among youth in the foster system (Ahrens et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2010; Greeson et al., 2010, & Munson et al., 2010), including relationships and/or experiences with adults that youth felt were unhelpful or aversive as well as relationships that they youth regarded as positive but that might not fit with the traditional definition of a natural mentoring relationship. Following from this, we elected not to make use of a pre-set definition for a mentoring relationship as has often been done in prior research (e.g., Rhodes, Contreras, & Mangelsdorf, 1994). Our broader aim in carrying out the research was to use our findings, in combination with those of prior research, to generate a set of testable hypotheses regarding how beneficial relationships with mentors and other non-parental support figures can be cultivated and supported for youth involved in the foster care system, to improve outcomes for this vulnerable population.

2. Methods

2.1 Sampling Strategy and Participants

Young adults (N=23) ages 18-25 years were selected to participate in this study through four non-profit agencies serving current/former youth in foster care in an urban area (Seattle, WA). The agencies were chosen because they served youth in foster care in a variety of ways, including the provision of independent living services to a broad range of youth (1 agency), intensive support services for high risk youth (1 agency), housing (2 agencies), and/or scholarship support for high achieving youth (1 agency). Purposive and snowball sampling strategies were employed, with the goal of gaining the perspectives of a variety of young adults with foster care system involvement who were experiencing varied levels of success in their transition to adulthood.

2.2 Interview Procedure

After obtaining written informed consent, semi-structured in-person interviews were completed by two investigators, both of whom were middle-class Caucasian women (the principal investigator and a research coordinator). Interviews typically lasted about 60 minutes (range: 30 to 90 minutes) and were conducted at a site of the participant's choosing, usually at or near the recruitment agency. Informed consent was obtained prior to each interview and participants were paid $25. Main topics of discussion and example questions for of these topics were developed a priori. As described in the introduction, because we were interested in learning about the youth's relationships with all potentially important adults, at the start of the interview participants were asked a non-specific question about the important adults in their lives other than their foster or biological parents when they were teenagers rather than being given a preset definition of a mentoring relationship as has been done in other studies (e.g., Rhodes et al., 1994). In addition, we also asked youth about relationships and/or experiences they felt were not helpful, to gain an understanding of the types of barriers that these young adults experienced in forming supportive relationships with potentially helpful adults.

An overview of all major topic areas covered in interviews is presented in Table 1. Participants were allowed to direct the interview, with investigators suggesting topics of conversation after significant lapses in conversation occurred. Immediately after each interview, the interviewer completed a contact summary sheet to briefly describe the content of the interview from her perspective. Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed, and then checked against the audio recording for accuracy by one of the investigators (usually the one who conducted the interview). All interviews were conducted in English except one, which was partially conducted in Spanish by the principal investigator who is proficient in this language. This interview was transcribed by a bilingual transcriptionist and then reviewed by the same interviewer. Preliminary reviews of both contact summary sheets and of transcripts as they became available were conducted on an ongoing basis. An iterative process was used to add new discussion topics to subsequent interviews based on the results of previous interviews. Interviews were conducted until no new themes arose (Charmaz, 2006). All procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Table 1. Summary of Discussion Topics Covered in Interviews.

| Talking Point | Initial or Added | Example Question |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Initial | “How old are you?” |

| Experiences in foster care | Initial | “Tell me about your experiences in foster care.” |

| Identification of adult mentors | Initial | “I would like to learn about helpful relationships that you had as a teenager with adults other than your biological parents or foster parents. Can you think of anyone that was helpful to you when you were a teenager?” |

| Exploration of the roles/impacts of mentoring relationships | Initial | “How did that person help you?” |

| Ongoing contact with mentors | Initial | “Do you still keep in touch with that person?” |

| Current satisfaction with life/ adaptation to adulthood | Initial | “Overall, how do you think your life is going right now?” |

| Unhelpful experiences with adults | Initial | “Were there ever any experiences with this person or another person that were not helpful? Can you give me an example?” |

| Transition out of the foster care system | Added | “Tell me about when you left the foster system.” |

| Experiences with mentoring programs | Added | “Did you ever have a mentor that was part of a mentoring program? Can you tell me about that experience?” |

2.3 Analysis

We used theoretical thematic analysis to analyze data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This technique is used to identify patterns and themes within qualitative data and to facilitate the development of interpretations of these data. It allows for the use of pre-existing theoretical frameworks, such as the one presented in the introduction of this paper (Rhodes, 2002, 2005; Rhodes et al., 2006). Analysis was performed by three investigators (the two interviewers and co-author Michelle Garrison, also a middle-class Caucasian woman) and, was done on an ongoing basis at the same time that interviews were being conducted. The principal investigator participated in the analysis of all transcripts; the other two investigators each analyzed approximately half of the transcripts. The investigators initially employed an incident-by-incident coding technique (Charmaz, 2006), in which every portion of the interview transcript was read and coded for important themes. This was followed by a focused coding process during which the incident codes were re-read and analyzed in order to identify larger themes (Charmaz, 2006). During both phases, investigators analyzed 3-5 interviews at a time and then met to discuss themes and resolve any discrepancies by discussion. Both to provide feedback to agencies and to check the validity our findings, a written report describing study findings was provided to the agency that was our largest site for recruitment (site 1). Current/former youth in foster care affiliated with this agency and staff members were encouraged to review the report and comment if so desired. Written comments were submitted by 2 persons (agency staff members) as well as from one staff member from another agency (site 4) from whom feedback was specifically solicited; these comments were incorporated into the final analysis of the data.

3. Results

3.1 Description of Participants

Participant (N=23) characteristics are described in Table 2. Over half of participants were female (61%) and the average age was 19.9 years (SD=2.2 years). They were diverse with regard to ethnic and racial background, as participants included members of 12 different racial/ethnic groups. Youth also reported a variety of experiences in foster care. Most youth had experienced more than one type of placement (i.e., kinship placements with family members, placements in non-kin family homes, and/or group care). With respect to placements during adolescence, approximately half of the youth had experienced stable placements in 1-2 homes during all or most of adolescence (N=12) whereas the remainder (N=11) reported multiple placements without experiencing a stable, long-term placement.

Table 2.

Description of Study Participants.

| Variable | Description of Participants |

|---|---|

| Gender (% female) | 61% (14) |

| Self-Reported Race/Ethnicitya | |

| - Caucasian or European | 30% (7) |

| - African American | 39% (9) |

| - Mexican or Latin American | 26% (6) |

| - Asian or Pacific Islander | 9% (2) |

| - Native American | 17% (4) |

| - African Native | 13% (3) |

| - Mixed | 22% (5) |

| Age | |

| - 18-19 years | 57% (13) |

| - 20-21 years | 26% (6) |

| - 22-25 years | 17% (4) |

| Experiences in Foster Care | |

| - Stable (≤2) vs. multiple placements (% stable)b | 52% (12) |

| - Placement typesb,c | |

| • Non-kin foster home | 83% (19) |

| • Kinship care | 22% (5) |

| • Group home | 39% (9) |

| Recruitment Sitec | |

| - Site 1 | 57% (13) |

| - Site 2 | 9% (2) |

| - Site 3 | 13% (3) |

| - Site 4 | 17% (4) |

| - Snowball | 4% (1) |

Categories are non-exclusive due to the high percentage of participants reporting being of mixed descent;

Reflects participants' self-report of experiences during adolescence;

Categories are non-exclusive due to the fact that most youth reported they had been in more than one placement during adolescence.

3.2 Description of Important Adults

The median number of adults that youth discussed was 2. All youth discussed experiences with at least one adult. The largest number of adults discussed was three. Youth reported current/ongoing contact with two-thirds (67%) of these adults overall; all but 1 participant reported current contact with at least one adult who had been important to them during adolescence.

Consistent with prior research on mentoring relationships among youth in foster care (Collins et al., 2010; Greeson et al., 2010), youth reported relationships with important, non-parental adults in three main categories: family members, adults involved with the youth in a professional role, and adults involved with the youth in an informal role. Many youth described relationships with non-parental adults they had met through their involvement with the child welfare system such as a caseworker, parole officer, or supervisor in a job-training program. Only two youth described ties with adults who they were connected with through a formal mentoring program. In addition, because we allowed the youth to direct the interview and to discuss persons and experiences that they felt were important, some youth discussed relationships that did not fit traditional criteria for an important non-parental adult mentor as has been previously defined in the literature (e.g., Rhodes et al., 1994). These included former foster parents, caseworkers, and mental health therapists; one youth also discussed a biological parent whom they related to “like a mentor”. Further examples of the types of adults discussed in each of the above categories are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Types of Non-Parental Adults with Whom Youth Reported Important Relationships.

| Category | Important Adults Described By Youth |

|---|---|

| Family Members |

|

| Adults Involved Professionally with the Youth | General:

|

| Adults Involved Informally with the Youth |

|

3.3 Themes

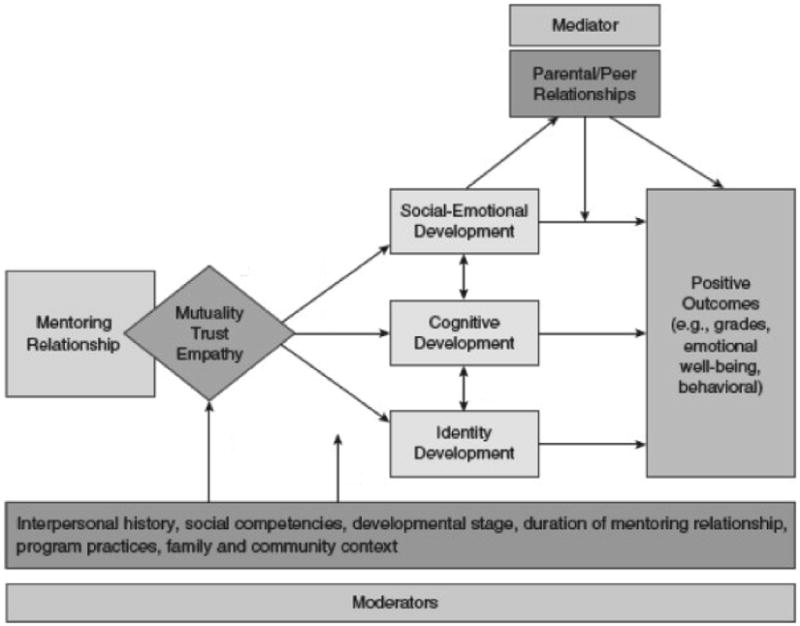

Several themes emerged that related to or expanded on aspects of Rhodes' conceptual model that was presented in the introduction (Rhodes, 2002, 2005; Rhodes et al., 2006). These include barriers and facilitators to forming the initial relationship, influences on the length and quality of established relationships, relationship impacts, and unmet needs. In the following section, themes in each of these categories will be described. Table 4 contains exemplary quotes for all themes/subthemes described; Figure 2 places these themes in the context of the Rhodes model.

Table 4.

Themes, Subthemes, and Exemplary Quotes.

| Theme | Subtheme | Exemplary Quote(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers to the initial connection | -Fear of the emotional risk | “I was just too hurt in my heart to even open up.” [Participant 5, female] |

| -Fear of indebtedness to the mentor | “Yeah, because I don't want people to be like, ‘Remember that one day I helped you with this?’ ” [Participant 3, male] | |

| -Fear that the mentor will fail the youth | “Well for people who are in foster care it is because you don't want to rely on someone else because they could just not do it and then that's your ass. I'd rather take it in my own hands and handle my own stuff.” [Participant 3, male] | |

| -Being pushed to bond too quickly | “For me people were always asking why don't you bond more quickly? Because it's just who I am.” [Participant 1, male] | |

| -Resistance to directive advice | “When I was a teenager I did not get along with adults because I have this mind where it has to be my way or I don't do it all. And like when elders try to tell you this is the way you do it, youngster, I'm like, ‘No, this is the way you do it and I know. Your way is old, mine's new.’” [Participant 3, male] | |

| -Adult lacks understanding of youth's culture or background | “…most of African culture they say if you are the youngest, you can't talk to someone if you look at their face…She say if you doesn't look me in my face, that's when you don't pay attention to me, and I was paying attention.” [Participant 12, female] | |

| Facilitators of the initial connection | -Adult has persistence/patience | “Yeah because at first I didn't even like her, I hated her. But she was trying so hard. And I saw that she cared, she didn't go off, like leave me alone like everybody else. She just kept trying and trying.” [Participant 7, female] |

| -Authentic displays of affection/ emotional support by adult | “The three main things…is put everything into helping that kid, show your body language, which means be yourself, show your eyes, show your emotion in your face, get into conversation with the kid…You've got to be with the kid, get a relationship with that kid; that's the number one thing. Try to get your whole body, your whole mind, you whole spirit into wanting to help that kid. And you're not trying to show it, you're trying to be yourself. That's how you will show it. ” [Participant 8, male] | |

| -Adult opens up/shares their own experiences | “I mean stepping outside of her job title as far as, like, she's a case manager. Those moments she shared about her life. They're not supposed to do that but it's optional for them. If they want to put their business out there to you, or whatever, it's optional. So for her to take that option and take it to the next level I really thought that that was really nice.” [Participant 10, female] | |

| -Adult goes beyond prescribed relationship | “…That meant that she really cared about me and she really had a big heart for me. Her job description is not helping kids find a place to stay, not calling up somebody, ‘This girl needs a place to stay right now.’” [Participant 5, female] | |

| -Adult respects youth & their past experiences | “Don't try to undermine them. Don't try to keep them as a little person because they won't like that.” [Participant 8, male] | |

| -Shared characteristics between youth and adult | “We were both like an outdoor-type of person, like we liked to do sports”“…she was in foster care, she was there, she could understand it more, than like my caseworkers understood it and they were so big in my life, but they didn't come from that same environment as I came from, so they could only understand it to a certain amount…” [Participant 21, female] | |

| -Youth experiencing a period of vulnerability/ need | “Yeah, actually I think what happened is I was in the most vulnerable position so when they came up to me they weren't really reaching out because they tried so many times after a while people just give up because they're like, ‘Why try? She's just going to brush me off her shoulder.’ So when I was at the most vulnerable position and they talked to me that's when I opened up.” [Participant 5, female] | |

| Barriers to the ongoing relationship | -Logistical barriers | Placement change or other move: “I think it [losing contact] was because of all the moving I did since I turned 18.” [Participant 7, female]Loss of contact information: “…I've been calling there trying to get to the schools that she is at. And I call them schools and they're like, ‘she's not here anymore, she's principaling at this school…And I can't remember for the life of me what apartment building she lives in.” [Participant 17, female]Mentor leaves/moves away: “Well she left DSHS so I tried to look for her when I got older and was stable just to say thank you, but I couldn't find her.” [Participant 6, female] |

| -Youth fear of not living up to adult's expectations | “I don't' feel that I've achieved what I need to achieve and I can't go back to her and tell her that I'm a failure so until I get where I want to be and where I know that I should be, I don't want to see her because…I can't do that to her.” [Participant 18, female] | |

| Facilitators of the ongoing relationship* | -Mechanism in place to maintain regular contact | “Yeah. She calls me every now and then, like every week or so. That's cool because usually I am busy.” [Participant 3, male] “He's always been there…He has always been willing to talk over the phone if I can't talk to him in person.” [Participant 16, male] |

| -Adult helps youth understand what to expect | “[She was] trying to tell me what to expect and what's going to be happening.” [Participant 10, female] | |

| -Adult plans activities that incorporate the youth's interests | “She'd usually ask me and I'd throw out ideas and then we'd just talk and say, ‘Okay that works we can do that.’ She gave me the option… And then she voiced her opinion about it.” [Participant 6, female] | |

| -Adult displays confidence | “The more confidence you have in yourself the better it is that you will be able to get something out of a kid.” [Participant 8, male] | |

| -Adult is responsive to the youth's needs | “…she was just like I called her one day, ‘Oh you want to meet?’ ‘Yeah’ and then she was like, ‘Oh,’ and she came and picked me up from school.” [Participant 23, female] | |

| -Adult shows consistency between actions and words | “You can say you understand and stuff and but to us it doesn't mean nothing if you don't act on it.” [Participant 1, male] | |

| Developmental impacts of the relationship | -Socio-Emotional Development | Healthy conflict resolution/Emotional self-regulation: “One thing I used to tell him was, ‘I'm not going to sit there and listen while you just talk smack to me or whatever because people are going to think I'm a punk and they're going to think I'm a pushover.’ He's like, ‘I understand what you're coming from with that, but there's some times where you got to stand up and defend yourself and there's some times where you just got to blow it off and laugh at it.’” [Participant 15, male]Ability to set boundaries on other relationships: “…they say I'm a caring person and I would give my last cigarette to someone if they needed it, you know? And she's like, ‘You can't do that when you're broke and you're living on the streets because people will take advantage.’ She just helps me with stuff like that.'” [Participant 7, female] |

| -Cognitive Development | Planning/executive function: “I used to have a really bad problem listening to people…I don't want nobody to tell me this, I don't want nobody to tell me that. But it really does help. Just to even consider, maybe just weighing out your pros and cons. If I listened to her, what's the pros and what's the cons? If I don't listen to her, what's the pro's and what's the cons? It was good.” [Participant 10, female]Acquisition of independent living skills: “…she taught me how to cook and she taught me how to drive and stuff.” [Participant 1, male] “She helped me a lot…not just with school, but I'm talking about to educate myself about living on my own and what kinds of skills I need to have.” [Participant 23, female] | |

| -Identity Development | Improved self-worth: “She was kind of the one who was like, ‘Don't give up. There's going to be people who say you can't do it.’ I had a lot of conversations with her about my family who would be like, ‘Oh yeah she's going to be pregnant by the time she's sixteen.’” [Participant 17, female]Increased social capital: “She goes, ‘But I'm actually here to actually help you get back on track. To help you get off probation, to help you do something right for yourself.’ And I was like wow. I really trusted her, you know, I believed in her and stuff. And I started to get on track on stuff. I was going to college; I had 2 jobs.” [Participant 5, female] | |

| Supports provided by the adult | -Tangible support | Assistance with work/educational goals: “He really steps out and tries to find resources to help me with college and stuff.” [Participant 1, male]Acquisition of housing: “They would help me get back in [to housing]. I have to be on a waiting list to get back in, but they would help me.” [Participant 4, female]Provision of normal teen experiences: “She introduced me to the camping world. She signed me up for camps and stuff.” [Participant 10, female] |

| -Emotional support | “I was feeling like, uh-uh, I can't do this. She said, ‘no you can do it’, and that thing give me [the ability] to be strong and try.” [Participant 12, female] | |

| -Serving as a role model | “And that's one of my biggest – what's the word I'm looking for – I look up to him. I admire him. I want to become a lawyer and the way I strive for that is the same way that he strived to become where he's at now.” [Participant 15, male] | |

| -Guidance/ advice | “I call her. If I like if I have a cold or a headache, I call her and tell her I feel sick and I don't know what to do…” [Participant 12, female] | |

| -Support as a parental figure | “I learned a lot of things from him because I've never really had a father figure and he's about the closest thing I've ever had to a dad. Even long after me and his daughter stopped being friends, me and him continued our friendship.” [Participant 19, male] | |

| Unmet needs | -Independent living skills | “I had to find my own place to live; I had to find out how to budget money. I had to figure out how to manage a cell phone.” [Participant 7, female] |

| -Relationship skills | “I can't fight for myself. I don't know how. I don't know how to stand up for myself when someone's doing something. I don't even know how to go up to my boyfriend and be like, ‘What is going on?’…I don't even know how to do it.” [Participant 4, female] |

In addition to the themes presented in this section, all “Facilitators of the initial connection” were also described as facilitators of the ongoing relationship but were not re-presented due to space limitations.

Figure 2.

Elaborated Conceptual Model of the Impacts of Mentoring Relationships for Youth in the Foster System

3.3.1 The Initial Connection

3.3.1.a Barriers to the Initial Connection

Youth raised several factors that they felt made it difficult for them to form a relationship with non-parental adults in their lives. They frequently reported such barriers even when describing relationships in which they eventually formed a supportive tie with the adult involved. Several participants, for example, reported a reluctance to enter into relationships with adults due to a fear that these relationships would have negative consequences. Some participants expressed that they put up barriers due to a fear of being hurt emotionally (“I don't really get like super close to no one. I got this big wall.”). Other youth reported a fear of owing something (“Because it was hard for me to have, to get things from other people without giving them anything in return.”) or that the adult would fail to meet their expectations (“There are a lot of people in this world who say that they care when they [don't].”). Some youth related their fears to their past histories of maltreatment or abandonment by adults (“I didn't believe in people. I thought that everyone was a liar.”). Although many specifically indicated that negative past experiences with biological parents or family members played a role in their mistrust (“I never had the love of my mother.”), past experiences with foster parents and/or other adults were indicated by some to have played a role as well (“it felt like to me the majority of adults just wanted to…destroy youth.”).

Several characteristics of the interactions styles of both youth and the adults in their lives also emerged as barriers to the formation of supportive relationships. For example, when discussing relationships or aspects of relationships with adults that had been difficult for them, some participants stated that they felt they were pushed too quickly to bond and/or that these adults were discouraged if the youth did not trust the relationship as quickly as the adult desired (“I just can't know the person for two days and expect me to be with them every day and tell them my life story. It could take them a while.”). Others indicated being discouraged by directive advice given by an adult (“[Teenagers in foster care] don't need advice; they feel like they want to do whatever they want…and also they don't mind [listen to] older people”). Several youth, in addition, reported that mentors displayed a lack of understanding of their culture or background as a barrier to the formation of relationships with adults (“They didn't come from that same environment as I came from, so they could only understand it to a certain amount”).

3.3.1.b Facilitators of the Initial Connection

Several further themes pertained to factors that youth felt made it easier to form relationships with non-parental adults. Most of these facilitators of the initial connection pertained to characteristics of the adult's initial interaction style with the youth. These characteristics included adults demonstrating persistence or patience even if the youth showed initial signs of rejecting the relationship (“She never gave up.”; “I most of the time wasn't the one going to her but she was coming to me because she knew.”), displaying genuine affection/authenticity (“Be yourself, show your eyes, show your emotion in your face.”; “She was always worried, she, more she than any others”) and conveying respect for the youth and their past experiences (“My mentors talk to me like an actual human being.”). Some, but not all, participants also indicated that having one or more characteristics in common with an adult made it easier to form a relationship. The specific characteristics cited varied across interviews included shared interests (“We were both like an outdoor-type of person, like we like to do sports”; “…she like the music that I liked”; “We've got little connections…”), gender or cultural background (“It's the only time in my life…the only person I had who was full-grown and a lot like me”), communication style such as a similar sense of humor (“We would joke around and have fun and I was really happy.”), and having had some experience with foster youth or with the system itself (“She was in foster care…she could understand it more.”). Several youth also reported that they established connections with important non-parental adults during periods of emotional vulnerability, such as while transitioning out of foster care (“…it was like three months before I was going to age out and stuff - I started to trust people (adults), I opened up more.”).

3.3.2 The Ongoing Relationship

3.3.2.a Barriers to the Ongoing Relationship

When discussing relationships that had become important to them, youth described several logistical barriers as having caused such relationships to be disrupted or have contact severed altogether. One frequently cited barrier was a foster care placement change or other types of move such as being emancipated from care (“I think it was because of all the moving I did since I turned 18.”) or another placement change including going to jail (“When you're in jail it's hard to contact anybody really.”). Other factors included losing the adult's contact information (“I forgot her cell phone number..”), the adult moving out of the area (“he left the country for a year”). A few youth, furthermore, reported that they were afraid to contact adults who had been important to them because they felt that they were not living up to the expectations or aspirations these adults had for them and they did not want to disappoint them (“She's been wanting to see me and I can't do it until I have something that I can show her that I have done.”).

3.3.2.b Facilitators of the Ongoing Relationship

Youth described several themes related to characteristics of youths' interactions with important adults that enhanced the perceived quality of relationships or from the perspective of the participants made it more likely that they would continue over time. These facilitators of the ongoing relationship included several characteristics cited in the previous section as important in establishing the relationship (e.g., patience, authentic displays of emotion, treatment of the youth with respect). Additional characteristics of adults that were perceived as facilitating ongoing relationships include genuineness or authenticity (“…just the way she expresses her self. She didn't act fake or whatnot”), adaptability to the youth's changing needs (“I guess he was flexible, he was tough flexible”), and being consistent and demonstrating accountability (“They had to be consistent”). Several youth also shared that they appreciated when adults helped them to know what to expect, especially when relationships were going to end (“He prepared me [for the relationship to end] about a year ahead of time.”). Most youth who identified an ongoing relationship with an important adult at the time of the interview had some mechanism in place that allowed them to maintain a routine of regular contact with one or more of these persons. These included regular attempts at contact by the adult and/or the youth having routine contact with the adult routinely for another reason, such as at a job site or as part of an independent living program. The frequency (i.e., daily, weekly or once or twice a year) and predominant type of contact (e.g., in-person, telephone, email) varied from relationship to relationship. Many youth indicated that they tended to maintain relationships with adults with whom they engaged in activities that incorporated the youth's interests (“She gave me the ability to choose what I wanted to do, pretty much.”). The specific role of the adult in the youth's life (i.e., whether the person was a family member or the youth had met the person in an informal or professional capacity) was not identified as a theme that was related to length or quality of relationship, although it should be noted that the qualitative nature and the small sample size of this study made assessment of this type of association difficult.

3.3.3 Developmental impacts of relationships with non-parental adults

The positive impacts of the relationships that youth described with important adults in their lives were quite varied and reflected several themes relating to how these adults had contributed to their development during adolescence. Some themes focused on socio-emotional development and specifically on learning skills important to healthy relationships, such as healthy conflict resolution, anger management (“He taught me how you're going to meet people that are going to make you mad all the time.”), and setting boundaries with peers. Youth also reported that important non-parental adults had helped them to learn how to plan or problem solve or had helped them to learn independent living skills that they previously lacked, thus indicating contributions to their cognitive development as well. Finally, youth indicated that important adults had contributed to their identity, both by helping them to understand their own potential/self-worth (Interviewer: “So he just helped you believe in yourself with your own goals.” Participant: “Yeah.”) and by connecting them with other people and/or resources (“He really steps out and tries to find resources to help me with college and stuff.”).

It was beyond the scope of this study to measure specific impacts of supportive relationships with non-parental adults on the adult functioning of foster care youth. We did, however, hypothesize several potential impacts of this nature during the analysis process (see Figure 2). These included increased educational attainment and acquisition of housing and improvements in emotional resilience and self-confidence, interpersonal skills,for handling conflict and setting boundaries in relationships, and skills for planning and goal-setting.

3.3.4 Supports provided by adults

Interviewers also explored the specific ways in which important non-parental adults were perceived to have produced these impacts. In response, youth indicated that important adults tended to provide a lot of emotional support as well as guidance and advice on a variety of issues (“He'll give me good advice of what to do”). Many youth expressed that such adults were their role-models for how they should act as adults (“I looked up to her.”). Some participants also reported receipt of tangible support, such as assistance with getting into college or acquiring stable housing. Other youth reported that important non-parental adults had provided them with normal experiences that they would have otherwise missed out on, such as going camping or having someone attend their graduation ceremony. Some youth also indicated that non-parental adults, both inside and outside of their families, had filled roles as substitute parental figures (“He's definitely dad material”).

3.3.5 Unmet needs

Consistent with our study design, participants reported a variety of levels of perceived success with their transition to adulthood (“Right now, this second, pretty good”; “I'm not completely up on my feet”; “My life is not going good at all”). As a consequence, a variety of types and degrees of unmet needs were expressed as well. For example, some youth reported that they were homeless and unable to find ways to fill basic needs such as housing (“Mostly I've been living with my friends right now because I can't even find an apartment”), whereas others indicated that they were living independently and attending college. These latter youth tended to report fewer, more specific unmet needs such as figuring out how to navigate college successfully (“The credit thing confuses me…I don't know what I am doing.”). Investigators also noted that many areas in which one or more participants expressed an unmet need, other youth indicated that an important non-parental adult had filled that need. For example, multiple youth conveyed that they felt they lacked skills to develop positive relationships in their adult lives, whereas others indicated that the important adults in their lives had helped them learn these skills.

3.3.6 Interviewer perceptions of the youth's relational style during the interview

In addition to the themes described above, during the coding process two of the investigators noted several themes that they felt related to the participant's style of relating to others as potentially revealed through the interviewing process. For example, youth who presented as confident and secure during the interviewing process tended to report forming relationships with non-parental adults easily and that these relationships or their influences had been sustained over time (“Yeah, it's been ten years. It still sticks with you.”). In contrast, some youth displayed body language and/or speech patterns that suggested an initial mistrust of the interviewer. These youth tended to report that it took them a long time to develop important relationships with non-parental adults (“Automatically my mind is pretty much set and don't get close to nobody, let nobody in”) but similar to more secure participants tended to report significant impacts of these relationships when formed (“She helped me a lot with personal problems that I had with my siblings and with my family…”). Finally, some youth also displayed anxious body language and/or described a lot of worries when discussing their relationships with non-parental adults. (“It's like hard because my mentors are never around. If they are, they are busy.”). Although these participants tended to describe relationships with multiple adults, they frequently also expressed many needs during early adulthood (“There is a lot for me to go through right now.”).

4. Discussion

This study contributes to a growing body of research that explores processes mediating the impacts of mentoring relationships for specific populations of youth, including those with heightened vulnerability for whom mentoring may take on added significance in fostering resilience (Zimmerman, Bingenheimer, & Behrendt, 2005). Results of the present investigation highlight several social, cognitive, and affective processes through which mentoring relationships have the potential to strengthen adult outcomes for youth who have been in foster care. In this regard, our findings are broadly consistent with, and thus lend support to, the major assumptions that underlie Rhodes' developmental model of youth mentoring. As we will discuss, our results also suggest potential directions for building on this framework to derive a model that more fully captures the most salient processes involved in mentoring youth in the foster system.

All participants discussed at least one relationship with an non-parental adult during adolescence, a finding which exceeds expectations based on data from previous studies of youth in foster care that have used formal definitions of natural mentoring relationships (Rhodes et al, 1994). This suggests that we were successful in capturing a broader range of relationships to allow us to better understand the barriers and facilitators of true mentoring relationships, as was the objective of our study. The categories of supports that youth described receiving from non-parental adults (i.e., guidance/advice, emotional support, instrumental/tangible support, parent-like support) are consistent with those described in prior studies of youth in foster care (Ahrens et al., 2008; McDonald et al., 2007; Munson et al., 2010), as were the types of adults youth identified as important (Ahrens et al., 2008; Munson et al., 2010). Of particular note, similar to Munson et al. (2010) and Collins et al. (2010), youth in our sample often discussed relationships with adults whom they had met in some way through the child welfare system as being particularly important to them. It thus appears that such adults may be an especially significant from which youth in foster care draw support.

Our findings are also consistent with results of prior studies specifically examining associations between mentoring relationships for current and former youth in foster care and outcomes in that they suggest that relationships with non-parental adults during adolescence may play a role in facilitating a range of positive outcomes including those relating to the youth's educational attainment and living situation as well as those relating to emotional well-being, interpersonal relationships, and coping. Several of these potential impacts (i.e., increased educational attainment, improved self-esteem, improved functioning in relationships) are consistent with those that have been associated with either natural mentoring relationships (Ahrens et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2010; Courtney & Lyons, 2009; Munson & McMillen, 2009) or programmatic mentoring relationships (Rhodes et al., 1999) for youth in the foster system in prior research. Others have not been previously described (i.e. improvements in communication style or ability to handle conflict, improvements in executive functioning).

Notably, this is the first study to our knowledge to explore barriers and facilitators associated with the process of youth in the foster system developing relationships with important non-parental adults. Most of the themes that emerged concerning the initial development of relationships pertain to the personality or relationship style of the youth and/or the ability of the adults involved to tolerate and adapt to such characteristics. Among the salient themes in this area was that having some degree of commonality had made it easier for youth to connect with a non-parental adult. Perhaps part of the reason for the relatively consistent evidence of favorable impacts for naturally-formed mentoring relationships (Ahrens et al., 2008; Collins, Spencer, & Ward, 2010; Courtney & Lyons, 2009; Munson & McMillen, 2009) among youth in foster care is that the former relationships have formed in part based on such commonalities. The personal characteristics of prospective adult sources of support, including limitations in their interpersonal skills and understanding of the youth's background or culture, were also commonly cited as barriers to these relationships forming. Other factors cited as barriers to forming an initial connection pertain to the youth's ability to trust another person. This suggests that the youth's relationship style (specifically, his or her level of trust in others) may be important in determining whether and/or how quickly he or she will bond with a potential mentor. Finally, some youth indicated that they tended to seek out or accept help from adult support figures during periods of vulnerability, such as during their transition out of foster care. The implications of these findings will be discussed further below.

Factors that appear, based on the reflections of youth, to have contributed to the quality and longevity of their relationships with non-parental adults (i.e., facilitators) consistently involved characteristics of either the adult or the relationship itself. This aspect of our findings may be attributable in part to the fact that we obtained data from only a youth perspective. Overall, the more specific factors that youth reported as facilitators of either the initial or ongoing relationship were similar to those cited in the Spencer (2006) study of close and enduring formal mentoring relationships among youth in the general population (e.g., the presence of youth driven interactions, authenticity, persistence and communication of clear expectations by the mentor, the presence of common characteristics, and an ability on the part of the mentor to understand the youth's past experiences). Interestingly, however, the factors cited by youth as barriers to the continuation of relationships that had become important to them, specifically those involving logistical considerations as well as the youths' fears of disappointing adults who were important to them, are quite different from the barriers that have been cited in previous research on mentoring relationships established through programs. In an earlier qualitative study (Spencer, 2007) exploring failed programmatic mentoring relationships among youth in the general population, youth and mentors cited several relationship-oriented factors as reasons for why the match had terminated early including a lack of youth driven interactions, unrealistic or unfulfilled expectations of the youth by the mentor, and an inability to bridge cultural differences. These characteristics are similar in focus to many of the factors described by youth in our study as facilitators to the initial or ongoing relationship (i.e., the presence of youth driven interactions, the communication of clear expectations by the mentor, and the presence of common characteristics and an ability on the part of the mentor to understand the youth's past experiences). It may be that supportive bonds with non-parental adults do not tend to develop on their own if major barriers exist relating to the adult's personality or relationship style. Put another way, similar characteristics of non-parental adults may be important in relationships formed both in and out of mentoring programs, but these may factors come into play notably earlier (i.e., prior to the formation of the relationship) in those cultivated outside of a formal program. Alternatively, the differences between our findings and those of earlier studies (Spencer, 2006, 2007) also may reflect fundamental differences in the needs and characteristics of youth involved with the child welfare system compared with youth in the general population. These include potential residual trust issues with adults stemming from earlier life experiences (Alexander, 1993; Gauthier et al., 1996; Katsikas, 1996; Trapp, 1996, Weinfield, et al., 2000). Finally, we noted that a youth's relationship style also tended to impact the ongoing relationship. In this case, the youth's level of anxiety or worry in relationships appeared to influence both the chances that a relationship would continue, and the youth's perceptions of whether their needs had been met by this relationship. This will also be discussed further below.

5.1 Hypotheses for Effective Practices in Mentoring Foster Care Youth

With our findings, along with their connections to prior research and potential interpretations in mind, we now turn to consideration of what they suggest as possible effective strategies when designing programs and policies to support mentoring of youth with experience in the foster care system. Given the exploratory nature of our own investigation, the limited empirical knowledge base that is available to draw upon more generally in this area, we frame our ideas as hypotheses to examine in future research, not as recommendations for current practice.

First, given that in this and other studies youth in the foster system have been demonstrated consistently to rely on non-parental adults for support as they age out of care (Ahrens et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2010; Greeson et al., 2010; Munson et al., 2010), we believe that it would be useful to examine the benefits of having such persons more formally incorporated into planning that occurs in preparation for the youth's transition out of the foster care system. We see several potential advantages of this strategy. Non-parental adult support figures may have unique insights into the needs of youth and thus strengthen the base of information that is available to human services personnel formally charged with their transition planning. Additionally, such adults by virtue of their role in the youth's social network may be in a position to offer critical ongoing support and encouragement for the realization of goals that are set in the transition process. For those who may have played a formal role in the youth's care at earlier points in time (e.g., previous caseworkers or foster parents who have remained invested in the youth's care, job training supervisors), the process could also offer them a meaningful opportunity for providing support without feeling that they are overstepping professional role boundaries (which was cited as a concern by one agency staff member involved with the current research). Finally, the process of engaging important non-parental adults in the lives of foster care youth could serve to enhance the child welfare system's awareness of their significance in youths' lives, and thus be a catalyst for efforts to be of help in overcoming the types of logistical factors that were cited as barriers to maintaining such ties in the present study. Likewise, the involvement of such adults in transition planning could also serve as an opportunity to help youth prepare for new phases in their relationships with these support persons and, where necessary, for the ending of relationships. In this way, it may be possible to reduce potential negative interpersonal impacts of the transition out of foster care (Spencer et al., 2010). This type of preparation was specifically identified by one youth in the current study as an important factor influencing his appraisal of his relationship with one important non-parental adult.

A second hypothesis that we propose for investigation is that it will be beneficial for formal mentoring programs to implement specialized training for mentors of youth in foster care that reflects attention to issues suggested by research to influence the quality and duration of mentoring relationships for this population of youth. Such training could be to used as a vehicle in part for increasing the awareness of characteristics and experiences of adolescents in foster care that have the potential to present challenges to forming a bond with a mentor, and could be coupled with practical strategies for addressing such concerns, such as regularly discussing with the youth his or her experiences and expectations within the relationship.

Third, we also can hypothesize that greater attention to the criteria on which foster care youth are matched with mentors in formal mentoring programs would be beneficial. Based on our findings, it appears that it may be particularly valuable for this population of youth to be matched with mentors with whom they are likely to perceive themselves as sharing meaningful similarities in areas such as personal interests or life experience. It may also be beneficial to consider matching foster youth, and other youth with histories of abuse and neglect as well, with mentors who have specific training as helping professionals. Being in a helping profession has been shown to moderate the effect size of impacts of programmatic mentoring relationships (DuBois et al., 2002). Adults with this background may therefore be especially equipped with the patience and emotional security necessary to bond effectively with difficult and/or resistant youth. Additionally, although clearly preliminary, our findings also suggest the potential value of taking into account the relational styles of youth and mentor in the matching process. Within the realm of psychotherapy, there is some evidence of superior outcomes for client-counselor pairs in which the therapist utilizes a complementary relationship style to that of the client with regard to issues such as relative degree of reliance on self or others, compared with pairs in which the therapist models a similar style of relationship orientation (Bernier & Dozier, 2002). It has been hypothesized that exposure to an alternate interaction style can serve as a “corrective experience”, allowing clients to learn to be more flexible and functional their interactions with others. Exposure to alternative styles of approaching interpersonal interactions in the context of mentoring relationships might be similarly beneficial for youth in foster care, given the potential in this population for long-term negative ramifications of exposure to other less adaptive interpersonal models (Alexander, 1993; Gauthier et al., 1996; Katsikas, 1996; Trapp, 1996; Weinfield, et al., 2000). However, we qualify this hypothesis by acknowledging that not all studies in the psychotherapy domain have supported the benefit of complementary relational styles; more research is needed to determine the specific contexts in which and individuals for whom exposure to a complementary relational style in the context of a helping relationship is beneficial (Bernier & Dozier, 2002). We suggest, however, that adult attachment theory may be a useful framework to inform such future research exploring the implications of youth and mentor relationship style in mentoring relationships (for a review of adult attachment theory and its applications, see Crowell, Fraley, & Shaver, & Cassidy, 2008).

Fourth, we hypothesize that it would be beneficial to make training available to help prepare adolescents in the foster system to cultivate rewarding relationships with adults who represent potential sources of support in their lives. Such training has the potential to prove especially valuable for those who show maladaptive or counterproductive tendencies in their interactions with adult support figures as well as those who may be actively avoiding such relationships altogether. Although this idea once again represents a preliminary formulation, it is possible that this type of training might help enable youth to seek out their own “corrective experiences” at their own pace, and consequently increase the chances that youth in foster care successfully bond with and maintain relationships with supportive adults who care about them. We anticipate value for this type of training and support when offered either within the context of a foster care youth's participation in a formal mentoring program or more generally with a focus on their existing network of adult relationships, for example in the context of independent living programs.

Finally, the fact that some youth expressed that they were more open to accepting help during times of vulnerability suggests that the timing of the initiation of these relationships may be important. Although somewhat unexpected/counterintuitive, based on what participants said in this study we hypothesize that youth may be more open to connecting with adult mentors from formal programs prior to and during their transition out of care, and potentially during other times of vulnerabililty as well (e.g., at the time of their initial placement in foster care or a change to a new foster home). Mentoring programs for youth in foster care that focus on identifying youth during or ideally prior to these transitions and connecting them with mentors may find the chance of a successful (i.e., long-term) bond between mentor and mentee increased. In addition, the potential benefits of these relationships during such vulnerable times may be greater in that they could serve to mitigate the negative interpersonal impacts of such transitions as well.

Research to investigate the above-proposed hypotheses should be undertaken using rigorous methodology appropriate to the questions being addressed (DuBois et al., 2006). Initial, exploratory research should be conducted with the aim of informing the development of programmatic and service innovations and assessing both their feasibility and acceptance by youth and other stakeholders. Subsequent investigations then could be designed to yield reliable information as to the impact of innovations, both proximally on mentoring relationship quality and duration, and more distally on outcomes of interest for youth in foster care. Ideally, such studies would utilize experimental or rigorous quasi-experimental designs that allow for comparison of outcomes across those youth experiencing targeted practices or services relative to those experiencing care as usual (DuBois et al., 2006). Programmatic research along these lines is likely to prove challenging, especially when considering the limited resources of the child welfare system as well as the instability that characterizes the lives of many youth in foster care. We believe, however, that it has the potential to make a vital contribution to both maximizing benefits and minimizing the potential for harm with respect to the role of mentoring in supporting the successful transition of this vulnerable population of youth into adulthood.

5.2 Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, we cannot generalize the results from this qualitative study to a random sample of youth in foster care. Indeed, participants from this study all came from one urban area and their experiences came mainly from interactions with one state's child welfare system. Second, all interviewers and persons conducting the analyses were middle class white women. This reality necessarily influenced the way in which we analyzed and interpreted the data. It is possible that with a more diverse analytic team we may have gleaned additional or different themes from the data. Finally, the interviews we conducted offer only a one-time retrospective account and one that is limited to perspective of the youth. Accordingly, future research that assesses youth-adult dyads at multiple time points and that includes interviews with mentors would be helpful.

6. Conclusions

Overall, our findings suggest that relationships with important, non-parental adults represent an important source of support for the former youth in foster care, but that many factors can be involved in mediating their initial formation, stability over time, and value in fostering positive youth outcomes. We have highlighted several potential ways in which relationships with important adults formed in and outside of formal programs could potentially be better supported to improve outcomes for youth in foster care, including the systematic incorporation of important non-parental adults into the transition planning process for youth who are exiting the foster care system, improved training and matching strategies for mentors in formal mentoring programs, assisting youth with developing the interpersonal awareness and skills to take advantage of opportunities for support from non-parental adults, and targeting efforts to link youth in foster care to adult support to periods of specific vulnerability and need. Action-research that systematically explores the feasibility and impact of such strategies has the potential to significantly advance efforts to improve outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Research Highlights.

Former foster youth in this study describe a range of positive impacts from their relationships with non-parental adults.

Barriers and facilitators of these relationships were also highlighted; factors influencing whether youth in foster care develop relationships with potential support figures appear to be distinct from those shaping the quality and longevity of such relationships once established.

Several strategies to better capitalize on non-parental adults as sources of support for foster care youth are proposed, including incorporation of such adults into transition planning and improved procedures for both mentor training and youth-mentor matching in formal mentoring programs serving this population.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by an NIH T32 grant (HPT32-10002-23) and an award to Dr. Ahrens from the Young Investigators Grant Program from the Ambulatory Pediatrics Association. We would like to thank Karlie Keller, Melody Newburn, Mavis Bonnar, Alexis Coatney, and the participants and other agency staff members that made this work possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahrens K, DuBois DL, Lozano P, Fan M, Richardson L. Naturally-acquired mentoring relationships and young adult outcomes among adolescents with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2010;25:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens K, DuBois DL, Richardson L, Fan M, Lozano P. Youth in foster care with adult mentors during adolescence have improved adult outcomes. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e246–252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander PC. The differential effects of abuse characteristics and attachment in the prediction of long-term effects of sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1993;8:346–62. [Google Scholar]

- America's Promise Alliance. Every child, every promise: Turning failure into action. 2006 Retrieved from the America's Promise Alliance website: http://www.americaspromise.org/Resources/Research-and-Reports/∼/media/Files/About/ECEP%20-%20Full%20Report.ashx.

- Barth RP. On their own: the experiences of youth after foster care. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1990;7:419–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Dozier M. The client-counselor match and the corrective emotional experience: Evidence from interpersonal and attachment research. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2002;39:32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Blome WW. What happens to foster kids: Educational experiences of a random sample of foster care youth and a matched group of non-foster care youth. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 1997;14:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Britner PA, Kraimer-Rickaby L. Abused and neglected youth. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 482–492. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, England: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung S, Heath A. After care: The education and occupation of adults who have been in care. Oxford Review of Education. 1994;20:361–374. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Measurement of individual differences in adolescent and adult attachment. In: Shaver PR, Cassidy J, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2nd. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 599–634. [Google Scholar]

- Collins ME, Spencer R, Ward R. Supporting youth in the transition from foster care: Formal and informal connections. Child Welfare. 2010;89:125–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A. Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child & Family Social Work. 2006;11:209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Terao S, Bost N. Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Conditions of youth preparing to leave state care. 2004 Retrieved from the Chapin Hall website: http://www.chapinhall.org/article)abstract.aspx?ar=1355.

- Courtney ME, Lyons S. Mentoring relationships and adult outcomes for foster youth in transition to adulthood. Paper session presented at the 13th annual meeting of the Society for Social Work and Research; New Orleans, LA. Jan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Daining C, DePanfilis D. Resilience of youth in transition from out-of-home care to adulthood. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29:1158–1178. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Holloway B, Valentine J, Cooper H. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:157–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1014628810714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Silverthorn N. Natural mentoring relationships and adolescent health: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:518–524. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.031476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Dolittle F, Yates BT, Silverthorn N, Tebes JK. Research methodology and youth mentoring. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:657–676. [Google Scholar]

- Farruggia SP, Greenberger E, Chen C, Heckhausen J. Perceived social environment and adolescents' well-being and adjustment: Comparing a foster care sample with a matched sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier L, Stollak G, Messé L, Aronoff J. Recall of childhood neglect and physical abuse as differential predictors of current psychological functioning. Child Abuse & Neglect, 1996. 1996;20:549–59. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JKP, Usher L, Grinstein-Weiss M. One adult who is crazy about you: Can natural mentoring relationships increase assets among young adults with and without foster care experience? Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JB, Rhodes JE. The test of time: predictors and effects of duration in youth mentoring relationships. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:199–219. doi: 10.1023/A:1014680827552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- H.R. 6893--110th Congress. Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 (enacted) 2008 Retrieved from http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h110-6893.

- H.R. 3443, 106th Cong. The Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 (enacted) Retrieved from http://www.ssa.gov/legislation/legis_bulletin_112499.html.

- Katsikas SL. Long-term effects of childhood maltreatment: An attachment theory perspective (doctoral dissertation) University of Arkansas; Fayetteville, AR: 1996. [Google Scholar]