Abstract

Strategies to improve the viability of steatotic livers could reduce the risk of dysfunction after surgery and increase the number of organs suitable for transplantation. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are major regulators of lipid metabolism and inflammation. In this paper, we review the PPAR signaling pathways and present some of their lesser-known functions in liver regeneration. Potential therapies based on PPAR regulation will be discussed. The data suggest that further investigations are required to elucidate whether PPAR could be a potential therapeutic target in liver surgery and to determine the most effective therapies that selectively regulate PPAR with minor side effects.

1. Introduction

Liver transplantation has evolved as the therapy of choice for patients with end-stage liver disease. However, the waiting list for liver transplantation is growing at a rapid pace, whereas the number of available organs is not increasing proportionately. The potential use of steatotic livers, one of the most common types of organs in marginal donors, for transplantation has become a major focus of investigation. However, steatotic livers are more susceptible to ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, and the transplantation of steatotic levels results in a poorer outcome than that of nonsteatotic livers. Indeed, the use of steatotic livers for transplantation is associated with an increased risk of primary nonfunction or dysfunction after surgery [1, 2]. In hepatic resections, the operative mortality associated with steatosis exceeds 14%, compared with 2% for healthy livers, and the risks of dysfunction after surgery are similarly higher [2, 3]. Despite advances aimed at reducing the incidence of hepatic I/R injury (summarized in earlier reviews) [1, 2], the results to date are inconclusive. In this paper, we review the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) and PPARγ signaling pathways in steatosis, inflammation and regeneration, three key factors in steatotic liver surgery [1–5]. Our review of the different strategies pursued to regulate PPAR in liver diseases may motivate researchers to develop effective treatments for steatotic livers in patients undergoing I/R. The potential clinical application of strategies that regulate PPAR in the setting of steatotic liver surgery is also discussed.

2. Characteristics of PPAR

PPARs belong to the hormone nuclear receptor superfamily and consist of three isoforms: PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARβ/δ. Of these, our group and others have demonstrated that PPARα and PPARγ are important regulators of postischemic liver injury [1, 2, 6, 7] that exert their effects on steatosis and inflammation, which is inherent in steatotic liver surgery [8–12].

Previous results indicate that the presence of fatty infiltration by itself in the liver (without any surgical intervention) does not induce changes in PPARα or PPARγ levels, as no differences were observed in the levels of these transcription factors between steatotic and nonsteatotic livers of a sham group of Zucker rats [13, 14]. These results contrast reports from the literature indicating high or low PPARγ levels in steatotic livers compared with those in nonsteatotic livers [15, 16]. These different results can be explained, at least in part, by differences in the level of PPARγ regulation between rats and mice [17], the different obesity experimental models evaluated, and the degree of steatosis. We reported that PPARγ expression levels in nonsteatotic livers during liver transplantation were similar to those observed in the sham group. However, increased PPARγ levels were observed in steatotic liver grafts [14, 18]. Thus, steatotic liver grafts are more predisposed to overexpress PPARγ. This is in line with clinical studies, in which PPARγ was upregulated in the livers of obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NALFD) [19]. Additionally, differences in PPARα expression were observed among different liver types. Indeed, steatotic livers are more predisposed to downregulate PPARα, when they are subjected to warm hepatic ischemia [13]. In line with these findings, PPARα is downregulated in the livers of obese patients with NALFD [20]. Findings such as these must be considered when applying the same pharmacological strategies indiscriminately to patients with steatotic and nonsteatotic livers because the effects may be very different.

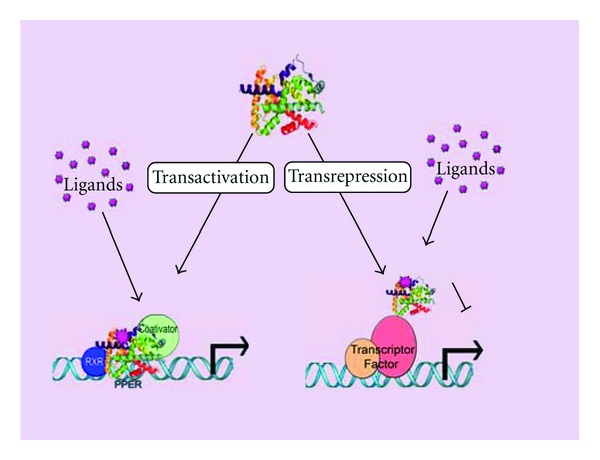

PPARs can both activate and inhibit gene expression by two mechanisms: transactivation and transrepression. Transactivation is DNA- and ligand-dependent. PPARs activate transcription in a ligand-dependent manner by binding directly to specific PPAR response elements (PPREs) in target genes as heterodimers with retinoid X receptor (RXR). Agonist binding leads to the recruitment of coactivator complexes that modify the structure of chromatin and facilitate the assembly of the general transcriptional machinery at the promoter [21]. Transrepression is ligand-dependent and may explain the anti-inflammatory actions of PPARs [22]. PPARs repress transcription by antagonizing the actions of other transcription factors [21] (see Figure 1). Physiologically, PPAR-RXR heterodimers may bind to PPREs in the absence of a ligand. Although the transcriptional activation depends on the ligand-bound PPAR-RXR, the presence of unliganded PPAR-RXR at a PPRE has effects that vary depending on the promoter context and cell type [22]. Further investigations on the structures of PPARs and the mechanisms by which PPARs regulate gene transcription may be useful for designing certain strategies, such as the use of PPAR antagonists or agonists. As shown in the following sections, the currently used pharmacological strategies aimed at regulating PPAR could not be incorporated into liver surgery due to their potential side effects.

Figure 1.

Basic mechanism of PPAR action. Receptor X retinoide, RXR; PPAR-response element, PPER.

Given the antiobesity and anti-inflammatory properties of PPARα and PPARγ [8–12], pharmacological interventions targeting these transcription factors could be a promising strategy to treat hepatic steatosis in patients undergoing I/R. However, as shown in Figure 1, the effects of pharmacological strategies aimed at modulating PPARs depend on the type of ischemia (cold or warm ischemia), the length of ischemia, and the type of the liver (nonsteatotic or steatotic liver).

3. Effect of PPAR on Hepatic I/R

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have examined both the I/R-inducedexpression of hepatic PPARα and the potential benefits of PPARα agonists under these conditions. According to previous studies by our group, PPARα mRNA and protein levels in nonsteatotic livers during I/R were similar to those of the sham group, and PPARα did not play a crucial role in I/R injury in nonsteatotic livers [13]. This contrasts studies published by Okaya and Lentsch [23] and Xu et al. [24], who reported the benefits of PPARα agonists in postischemic liver injury. The protective effects were possibly associated with reductions in neutrophil accumulation, oxidative stress, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) expression (Figure 2). Although the dose and pretreatment time of the PPARα agonist WY-14,643 were similar in both studies, Okaya and Lentsch [23] and Xu et al. [24], reported an ischemic period of 90 min [23, 24]; our ischemic period was 60 min, which is the ischemic period currently used in liver surgery [13]. Thus, 60 min of ischemia appears insufficient for inducing changes in PPARα levels in nonsteatotic livers. In nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and simple steatosis, treatment of mice with the PPAR activator Wy-14,643 protects steatotic livers against I/R injury, and the benefits of this treatment potentially occur through the dampening of adhesion molecule and cytokine responses and activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and IL-6 production [25]. In steatotic livers undergoing warm ischemia, PPARα agonists can limit the damage induced by I/R. PPARα agonists as well as ischemic preconditioning (PC) through PPARα inhibited mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) expression following I/R (Figure 2). This in turn inhibited adiponectin accumulation in steatotic livers and adiponectin worsening effects on oxidative stress and hepatic injury [13]. Given these data, PPARα regulation could be an alternative method for reducing the greater oxidative stress incurred by steatotic livers. Indeed, preventing I/R injury in steatotic livers via therapies aimed at inhibiting reactive oxygen species (ROS) production has proven difficult. Steatotic livers might produce SOD/catalase-insensitive ROS, which may be involved in the mechanism of failure of steatotic livers after transplantation [26]. Moreover, gene therapy based on antioxidant overexpression is limited by the toxicity of the vectors [2, 27]. In a recent study of nonsteatotic livers undergoing warm hepatic ischemia, the dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) increased hepatic n-3 PUFA content and reduced hepatic n-6/n-3 PUFA content. This was associated with PPARα upregulation, which in turn reduced NF-κB signaling and oxidative stress, leading to a reduced inflammatory response [28].

Figure 2.

PPAR and hepatic I/R injury. Angiotensin II, Ang II; epidermal growth factor, EGF; insulin-like growth factor, IGF; interleukin-6, IL-6; mitogen-activated protein kinases, MAPKs; nuclear factor kappa B, NFκB; PPARα agonist; pioglitazone, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, PPAR; ischemic preconditioning, PC; retinol binding protein, RBP4, PPARα agonist; Wy-14,643.

The function of PPARγ in hepatic I/R injury is unclear. Previous results in liver transplantation studies indicated that I/R did not induce changes in PPARγ expression in nonsteatotic livers, and consequently, strategies based on PPARγ regulation had no effect on hepatic injury [14]. These results were different from those observed in nonsteatotic livers under warm ischemia conditions [6]. In that study, treatment with pioglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, significantly inhibited hepatic I/R injury (Figure 2). The protective effect was associated with the downregulation of several proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and neutrophil accumulation [7]. This is in line with other results indicating that PPARγ-deficient mice displayed more severe injuries than untreated mice under warm ischemia conditions [6]. Furthermore, pioglitazone treatment inhibited apoptosis and significantly improved the survival of mice in a lethal model of hepatic I/R injury [7]. Previous studies indicated that PPARγ activation inhibits the release of TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 by macrophages [29, 30], which could be of interest in steatotic livers. Indeed, under warm hepatic ischemia, higher IL-1 and lower IL-10 levels were detected in steatotic livers after reperfusion than in nonsteatotic livers [31]. This imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory ILs increased oxidative stress and decreased the tolerance of steatotic livers to I/R. In addition, different studies have reported proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles of TNF-α and IL-6, respectively, in the vulnerability of steatotic livers undergoing I/R [2, 32].

Previous results indicated that PPARγ activation in hepatocytes by rosiglitazone treatment increases autophagy and protects against hepatic I/R injury. Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved cellular process for recycling of old proteins and organelles via the lysosomal degradation [33]. Thus, these results suggest that PPARγ has anti-inflammatory properties and therefore may be relevant during hepatic I/R injury. In line with these data, PPARγ upregulation is a key mechanism of the benefits of different pharmacological or surgical strategies for steatotic livers undergoing I/R. Thus, some results based on isolated perfused livers indicated that the addition of growth factors (epidermal growth factor (EGF) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I)) to University of Wisconsin (UW) preservation solution protected steatotic livers due to PPARγ overexpression [34]. Similarly, EGF pretreatment mediated by PPARγ overexpression protected steatotic livers undergoing warm ischemia [35] (Figure 2). Moreover, in warm hepatic ischemia, PPARγ upregulation was a key mechanism of the benefits of pharmacological blockers of angiotensin II (angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and Ang II receptor antagonists) on steatotic livers [36]. However, the role of PPARγ in hepatic I/R injury could depend on the surgical conditions, as a recent study of liver transplantation indicated that treatment with a PPARγ antagonist was effective in steatotic livers, suggesting a detrimental role of PPARγ under these conditions [14]. In line with this finding, PPARγ inhibition was a key mechanism of the benefits of RBP4 treatment and PC on steatotic liver grafts [14]. Considering these results, drugs targeting PPARγ regulation can potentially increase the number of organs suitable for transplantation, as these drugs can improve the outcome for marginal grafts that would not otherwise have been transplanted. However, the data on PPARγ reported in steatotic liver transplantation models with standard liver graft sizes should not be extrapolated to small-size steatotic liver grafts. In the case of small liver transplants, the liver regeneration inherent in this surgical procedure and the mechanism of hepatic damage derived from the removal of hepatic mass should be considered [1, 31, 36]. In small liver grafts the periods of ischemia ranged 40–60 min, whereas the periods of ischemia ranged 6–8 hours for cadaveric donor liver transplantation.

4. Effect of PPAR on Hepatic Steatosis

Numerous studies suggest that the actions of PPARα can prevent steatosis. Mice deficient in PPARα develop hepatic steatosis when fasted or fed a high-fat diet [37, 46, 57]. Treatment with a PPARα agonist decreased hepatic steatosis in mice on a methionine- and choline-deficient (MCD) diet [37]. Activation of PPARα by the agonist Wy-14,643 ameliorated alcoholic fatty liver- and MCD-induced steatohepatitis [37, 38]. The critical role of PPARα in ameliorating steatosis is mediated through the regulation of a wide variety of genes involved in peroxisomal, mitochondrial, and microsomal FA β-oxidation systems in the liver [58]. When steatotic livers are submitted to certain stresses much as partial hepatectomy, the activation of PPARα by bezafibrate reduces the availability of FAs from circulation, reducing thus the hepatic sphingolipid synthesis [40] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of strategies that regulate PPAR on hepatic injury, steatosis, and regeneration in experimental models and patients. Angiotensin II: Ang II; choline deficient: CD; epidermal growth factor: EGF; high-fat diet: HFD; insulin-like growth factor 1: IGF-1; methionine choline deficient: MCD; nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: NASH; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: PPARs; polyunsaturated fatty acids: PUFAs; ischemic preconditioning: PC; retinol binding protein-4: RBP4.

| PPARα | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPARα activators | |||||

| Strategies | Time | Effect | Experimental model and patients | Steatosis and hepatic injury | Regeneration |

| WY-14,643 (30 μmol/kg/d) [17] | 3 weeks | ↑ PPARα | Obese Zucker rats | ↑ β-oxidation of fatty acids | Not evaluated |

| WY-14,643 (180 μmol/kg/d) [17] | 1 week | ↑ PPARα | Ob/ob mice | ↑ β-oxidation of fatty acids;↓ triglycerides | Not evaluated |

| WY-14,643 (10 mg/kg) [23, 24] | 1 h before ischemia | ↑ PPARα | Mice or Rats; warm ischemia (90 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| WY-14,643 (10 mg/kg) [13] | 1 h before ischemia | ↑ PPARα | Zucker obese rats; warm ischemia (60 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| WY-14,643 (10 mg/kg) [25] | 10 days before surgery | ↑ PPARα | Foz/foz mice; steatotic livers; warm ischemia (90 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | ↑ cell cycle entry |

| Wy-14,643 (0.1%) [37] | 5 weeks | ↑ PPARα | Mice fed MCD diet | ↓ steatohepatitis | Not evaluated |

| Wy-14,643 (0.1%) [38] | 12 days | ↑ PPARα | Mice fed MCD diet | ↓ steatohepatitis; ↑ hepatic fatty acid oxidation | Not evaluated |

| Bezafibrate [39] | 5 weeks | ↑ PPARα | Mice fed MCD | ↓ hepatic triglycerides; ↑ hepatic fatty acid oxidation | Not evaluated |

| Benzafibrate (75 mg/kg) [40] | 7 days | ↑ PPARα | Rats; partial hepatectomy | ↓ availability of fatty acids; sphingolipid synthesis | ↓ liver regeneration |

| PC (5 min/10 min) [13] | Immediately before ischemia | ↑ PPARα | Obese Zucker rats; warm ischemia (60 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| n-3 PUFA (EPA (270 mg/kg) and DHA (180 mg/kg)) [28] | 7 days | ↑ PPARα | Sprague-Dawley rats; warm ischemia | ↓ hepatic injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress | Not evaluated |

| EPA (2700 mg/d) [41] | 1 year | ↑ PPARα | NAFLD patients | ↓ steatosis, hepatic injury, necroinflammation, and oxidative stress | Not evaluated |

| n-3 PUFA (1 g/day) [42] | 1 year | ↑ PPARα | NAFLD patients | ↓ steatosis, hepatic injury, and necroinflammation | Not evaluated |

| n-3 PUFA (2 g/day) [43] | 6 months | ↑ PPARα | NAFLD patients | ↓ steatosis, hepatic injury, necroinflammation, and hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| n-3 PUFA (2 g, 3 times daily) [44] | 24 weeks | ↑ PPARα | NAFLD patients with hyperlipidemia | ↓ steatosis and hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| Ω-3 FA (5 mL, thrice daily) [45] | 24 weeks | ↑ PPARα | NAFLD patients with dyslipidemia | ↓ steatosis and hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| Atorvastatin (20 mg/daily) [45] | 24 weeks | ↑ PPARα | NAFLD patients with dyslipidemia | ↓ steatosis and hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| Orlistat (120 mg, thrice daily) [45] | 24 weeks | ↑ PPARα | NAFLD patients with dyslipidemia | ↓ steatosis and hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

|

| |||||

| PPARα knockout | |||||

| Strategies | Time | Effect | Experimental model | Steatosis and hepatic injury | Regeneration |

|

| |||||

| PPARα-knockout [23] | — | ↓ PPARα | PPARα-null mice Warm ischemia (90 min) | ↑ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| PPARα-knockout [46] | — | ↓ PPARα | PPARα-null mice fed HF diet | ↑ hepatic β-oxidation | Not evaluated |

| PPARα-knockout [47] | — | ↓ PPARα | PPARα-null mice Partial hepatectomy | Not evaluated | ↓ liver regeneration |

|

| |||||

| PPARγ | |||||

| PPARγ activator | |||||

| Strategies | Time | Effect | Experimental model | Steatosis and hepatic injury | Regeneration |

|

| |||||

| Rosiglitazone (10 mg/kg) [6] | 30 min before ischemia | ↑ PPARγ | PPARγ ± mice | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| Rosiglitazone (2.5 μmol/kg/d) [17] | 1 week | ↑ PPARγ | Ob/ob mice | ↓ triglycerides | Not evaluated |

| Rosiglitazone (3 mg/kg/day) [48] | 5 weeks | ↑ PPARγ | PPARγ fl/fl mice fed HFD diet | ↑ steatosis | Not evaluated |

| Rosiglitazone (1 mg/kg/day) [49] | 12 weeks | ↑ PPARγ | Obese C57BL/6J mice | ↑ steatosis | Not evaluated |

| Rosiglitazone (10 mg/kg) [50] | 2 days before surgery | ↑ PPARγ | Mice partial hepatectomy | Not evaluated | ↓ hepatic regeneration |

| Troglitazone (0.1%) + adPPARγ [51] | adPPARγ (5th day) troglitazone (5 days) | ↑ PPARγ | PPARα-null mice fed CD diet | ↑ steatosis | Not evaluated |

| Pioglitazone (500 μg/Kg) [52] | 8 weeks | ↑ PPARγ | Rat fed liquid diet + alcohol | ↓ liver injury | Not evaluated |

| Pioglitazone (30 mg) [53] | 96 weeks | ↑ PPARγ | Patients with NASH | ↓ steatosis | Not evaluated |

| Pioglitazone (25 mg/kg/day) [54] | 5 days before surgery | ↑ PPARγ | KK-AY, mice partial hepatectomy | Not evaluated | ↑ hepatic regeneration |

| Pioglitazone (20 mg/kg) [7] | 1.5 h before ischemia | ↑ PPARγ | Mice Warm ischemia (60 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| Ang II blockers Captopril (100 mg/kg) or PD123319 (30 mg/kg) [36] | Immediately before ischemia | ↑ PPARγ | Obese Zucker rats; warm ischemia (60 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| EGF and IGF-1 (10 μg/L) [34] | 24 h in UW solution | ↑ PPARγ | Obese Zucker rats; isolated liver perfused (24 h cold ischemia) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| EGF (100 μg/Kg) [35] | 3 doses (every 8 h) starting before surgery | ↑ PPARγ | Obese Zucker rats; warm ischemia (60 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| IGF-I (400 μg/Kg) [35] | 2 doses (every 12 h) starting before surgery | ↑ PPARγ | Obese Zucker rats; warm ischemia (60 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| Adenovirus PPARγ + rosiglitazone (50 mg/kg/day) [55] | 8 weeks | ↑ PPARγ | C57BL/6J mice fed MCD diet | ↓ steatohepatitis and fibrosis | Not evaluated |

| PC (5 min/10 min) [36] | Immediately before ischemia | ↑ PPARγ | Obese Zucker rats; warm ischemia (60 min) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

|

| |||||

| PPARγ inhibitor | |||||

| Strategy | Time | Effect | Experimental model | Steatosis and hepatic injury | Regeneration |

|

| |||||

| GW9662 (1 mg/kg) [14] | 1 h before surgery | ↓ PPARγ | Liver transplantation (6 h cold ischemia) | Does not change in hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| GW9662 (1 mg/kg) [14] | 1 h before surgery | ↓ PPARγ | Steatotic liver transplantation (6 h cold ischemia) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| GW9662 (1 mg/kg, 3 times/week) [55] | 8 weeks | ↓ PPARγ | C57BL/6J mice fed MCD diet | ↑ steatohepatitis, fibrosis and hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| RBP4 (150 μg/kg) [14] | 30 min before surgery | ↓ PPARγ | Steatotic liver transplantation (6 h cold ischemia) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

| PC (5 min/10 min) [14] | Immediately before ischemia | ↓ PPARγ | Steatotic liver transplantation (6 h of cold ischemia) | ↓ hepatic injury | Not evaluated |

|

| |||||

| PPARγ inhibitor | |||||

| Strategies | Time | Effect | Experimental model | Steatosis and hepatic injury | Regeneration |

|

| |||||

| PPARγ-knockout [56] | — | ↓ PPARγ | Liver-specific PPARγ-null mice | ↓ steatosis | Not evaluated |

It is well known that n-3 PUFAs and their derivative FAs activate PPARα [59–61], which then heterodimerizes with RXR and liver X receptor, leading to the transcription of a large number of genes involved in lipid metabolism. It has been reported that n-3 PUFAs are more potent than the n-6 PUFAs as in vivo activators of PPARα [59]. In addition, PUFA metabolites such as eicosanoids or oxidized FAs have one to two orders of magnitude greater affinity for PPARα and are consequently far more potent transcriptional activators of PPARα-dependent genes [59].

The interaction of PPARα with its DNA recognition site is markedly enhanced by ligands such as hypotriglyceridemic fibrate drugs, conjugated linoleic acid, and PUFAs [59]. The discovery of PPARα led quickly to the idea that PPARα was a “master switch” transcription factor that was targeted by PUFA to coordinately suppress genes encoding lipid synthesis proteins and to induce genes encoding lipid oxidation proteins [59]. In line with this idea, recent studies suggested that n-3 FAs serve as important mediators of gene expression, working via the PPARs to control the expression of the genes involved in lipid and glucose metabolism and adipogenesis [61]. Neschen et al. [62] demostrated that the administration of dietary fish oil (n-3) to rats increases the FA capacity of their livers through its ability to function as a ligand activator of PPARα and thereby induces the transcription of several gene-encoding proteins affiliated with FA oxidation. Of interest, other studies examining the effects of fish oil feeding on the expression of several genes of PPAR knockout mice clearly indicated that hepatic gene regulation by fish oil feeding involves at least two different pathways: PPARα-dependent and PPARα-independent pathways. Enzymes for peroxisomal (CYP4A2) and microsomal (AOX) oxidation are PPARα-dependent and upregulated by fish oil feeding, whereas those for lipid synthesis (FAS; S14) are PPARα-independent and downregulated. This indicates that the FA regulation of de novo hepatic lipogenesis and FA oxidation are not mediated through a common factor (e.g., PPARα) [61].

Given all these data into in account, the regulation of PPARα by PUFA, particularly n-3 PUFA and possibly conjugated linoleic acid, may offer an explanation for the reported benefits of these FAs in different pathologies.

In obese NAFLD patients, the increased production of ROS leads to the depletion of n-3 PUFAs due to enhanced lipid peroxidation. As PPARα is activated through direct binding to n-3 PUFA, liver PPARα function is compromised in obesity. This prevented the upregulation of genes involved in lipid transport, FA β-oxidation and thermogenesis, favoring FA and triacylglycerol synthesis over FA β-oxidation and thus promoting hepatic steatosis [20]. Thus, PPARα activation by n-3 PUFA supplementation ameliorated hepatic steatosis in obese NAFLD patients [20]. In line with this, NASH patients have low levels of circulating n-3 PUFA, with a consequent increase of the n-6/n-3 FA ratio and impaired PPARα activity in the liver [42, 43]. NASH patients treated with eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) or n-3 PUFAs, a mixture of EPA and docosahexaenoic acid, exhibited improvements in hepatic steatosis and necroinflammation in humans and rats with NASH, probably due to the reduction of hepatic TNFα expression and improvement of insulin sensitivity [41–43]. Moreover, PUFAs activate PPARα, leading to increased FA β-oxidation; hence, they can shift the energy balance from storage to consumption [41, 43]. n-3 PUFAs have also been proved as safe and efficacious for patients with NAFLD associated with hyperlipidemia, as indicated by reduced hepatic damage and serum lipid levels [44]. In another study, the efficacy and safety of three hypolipidemic, agents in patients with NAFLD with dyslipidemia were evaluated. In this context, predominantly hypertriglyceridemic, hypercholesterolemic, and overweight patients were treated with n-3 FAs, atorvastatin, and orlistat, respectively. The three different groups of patients exhibited reduced hepatic damage, normalized of hepatic steatosis, and reduced serum lipids [45].

Considering that steatosis is a risk factor in liver surgery, strategies aimed to reduce steatosis could increase the tolerance of steatotic livers to I/R. There is considerable evidence that liver regeneration is impaired in certain genetic models in which the liver contains excess fat. For example, steatotic livers from Ob mice exhibit defective liver regeneration and high mortality following partial hepatectomy [63]. Similarly, impaired liver regeneration was observed in steatotic livers undergoing partial hepatectomy under vascular occlusion compared with that in nonsteatotic livers [31]. On the contrary, drugs that reduce hepatic steatosis, such as PPARα regulators, should be considered with caution in clinical liver surgery, as other studies indicate that genetic or pharmacologic approaches that reduce lipid accumulation may also hinder liver regeneration [63–66]. Thus, a question is to what degree should we reduce steatosis in steatotic livers to protect this type of liver. Another question is whether we should reduce steatosis before the surgical procedure and therefore avoid the vulnerability of steatotic livers to I/R, or in contrast, should we use drugs aimed at reducing hepatic triglycerides during surgery and thus conserve the energy required for liver regeneration. Moreover, research evaluating whether the short-term administration of PPARα agonists might alleviate hepatic steatosis in steatotic livers before I/R would be of interest for clinical practice because there are obvious difficulties concerning the feasibility of long-term PPARα agonist administration in some I/R processes, in particular liver transplantation from cadaveric donors, because this is an emergency procedure in which there is very little time to pretreat the donor with PPARα agonists.

Several studies attribute a causal role to PPARγ in the development of steatosis by mechanisms involving the activation of lipogenic genes and de novo lipogenesis [48, 51]. In accordance, targeted deletion of PPARγ in hepatocytes protects mice against diet-induced hepatic steatosis [67], suggesting a prosteatotic role of PPARγ. Similarly, mice with liver-specific PPARγ silencing are protected against hepatic steatosis [56]. Additionally, treatment of ob/ob mice with rosiglitazone increased liver steatosis [49]. By contrast, different results have been reported regarding the effect of PPARγ on hepatic steatosis. Indeed, PPARγ-deficient mice develop more severe MCD-induced NAFLD, whereas adenovirus-mediated PPARγ overexpression attenuated the progression of NASH [55]. In line with this finding, rosiglitazone treatment prevented the development of NASH in a model of MCD-treated mice [55], and similar results were obtained using the PPARγ agonist pioglitazone [52, 53]. These different results can be partially explained by differences in the studies such as the species, type of PPAR agonist, method to induce hepatic steatosis, the type of genetic strategy used to induce PPARγ overexpression or deficiency in PPARγ expression as well as differences in the pretreatment times of the drugs used (see Table 1).

5. Effect of PPAR on Hepatic Regeneration

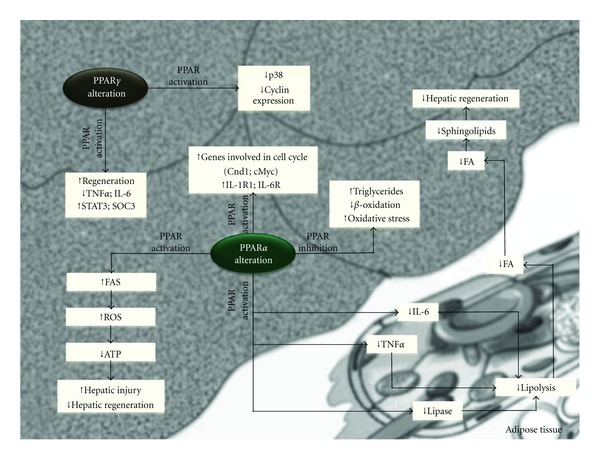

Recent studies demostrated that liver regeneration is impaired in a number of animal models of fatty liver disease [68–73]. PPARα-null mice subjected to partial hepatectomy (PH) have an impaired ability to regenerate hepatic mass. Emerging evidence suggests that PPARα is a critical modulator of the energy flux important for the repair of liver damage. For example, hepatocytes in the periportal regions, which divide and replicate after PH, require mitochondrial oxidation of FAs to generate energy [74]. PPARα controls the constitutive expression of genes involved in mitochondrial FA oxidation, including carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 [46, 75]. In mice deficient in PPARα, the impaired hepatic regeneration is also associated with the altered expression of genes involved in cell cycle control and cytokine signaling. Studies with PPARα agonists indicate that PPARα upregulates genes involved in the cycle cell (Ccnd1 and cMyc) as well as IL1r1 and IL-6r [76] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PPAR and hepatic regeneration. Adenosine triphosphate: ATP; fatty acid: FA; interleukin-1 receptor: IL-1R; interleukin-6: IL-6; interleukin-6 receptor: IL-6R; tumor necrosis factor-alpha: TNF-α; signal transducer and activator of transcription 3: STAT3; suppressor of cytokine signalling 3: SOC3; reactive oxygen species: ROS.

It is well known that PPARα affects the transcription of a number of genes involved in lipid turnover and peroxisomal and mitochondrial β-oxidation, resulting in the generation of ATP, which is required to “fuel” liver repair and regeneration [76]. By contrast, in conditions in which PPARα function and/or expression is altered such as hepatic steatosis, and small-size liver grafts, FA metabolism is deviated toward the accumulation of inadequately metabolized fat, favoring ROS generation. Consequently, ATP production is decreased, and the demise of hepatocytes via necrotic cell death is increased, halting liver repair [77] (Figure 3). Accordingly, mice with targeted PPARα disruption exhibit increased inflammation and necrosis and delayed liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy [47].

Previous results indicate that the impaired liver regeneration of steatotic rats was partially due to PPARα downregulation through the AdipoR2 axis. The inhibition of PPARα signaling, increased triglyceride (TG) accumulation in hepatocytes and inhibited the expression of hepatic enzymes that contribute to FA oxidation (Figure 3). This was associated with increased lipid peroxidation and decreased antioxidant levels [78].

In contrast with the aforementioned data indicating the beneficial effects of PPARα on hepatic regeneration, a recent report indicated that PPARα activation by bezafibrate had negative effects on liver regeneration, which can be attributed to the inhibition of de novo sphingolipid synthesis [40]. Presumably, bezafibrate affects de novo sphingolipid synthesis by decreasing FA availability (Figure 3). The activation of PPARα by bezafibrate virtually obliterated the postoperative increase in plasma nonesterified FAs induced by PH. This can be explained by the inhibition of hormone-sensitive lipase activity in adipose tissue by PPARα ligands and their anti-inflammatory properties, which decrease the release of cytokines such as TNF and IL-6. Both events inhibited lipolysis in isolated white adipocytes, resulting in reduced FA release from extrahepatic sources after PH [40].

PPARγ activity is likely to be regulated during normal liver regeneration, and the disruption of this regulation could impair the regenerative response. Pioglitazone improved hepatic regeneration failure in obese mice. This effect was associated with reduced TNFα and IL-6 levels. Additionally, pioglitazone prevented the increased mRNA expression of signal transducer and activators of transcription-3 phosphorylation and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 mRNA in the livers of obese mice [54]. However, inconsistent results have been obtained regarding the effect of PPARγ of liver regeneration. Indeed, rosiglitazone inhibited hepatocyte proliferation in mice undergoing partial hepatectomy by reducing p38 and cyclin expression [50] (see Figure 3).

On the basis of the inconsistent results reported to date on the role of PPAR in hepatic regeneration, it is difficult to discern whether we should attempt to inhibit PPAR or administer PPAR activators to promote liver regeneration in surgery.

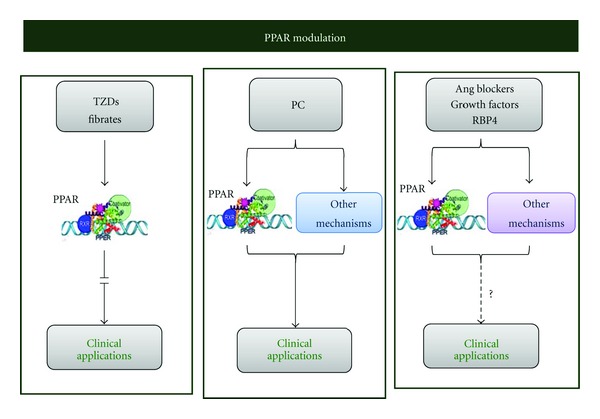

6. Modulators of PPAR in Clinical Practice

Based on the data reported in experimental models (as reviewed above), different strategies (which have been summarized in Table 1) could exert effects on steatosis, inflammation, or regeneration by regulating PPAR. Whether these pharmacological approaches can be translated into treatments for clinical liver surgery remains unknown. For example, thiazolidinediones (TZDs) should not be applied in clinical liver surgery due to their potential side effects. TZDs (pioglitazone, troglitazone, and rosiglitazone) are synthetic PPARγ agonists that are widely used as antidiabetic agents [79–81]. However, prolonged treatment of obese and diabetic mice with TZDs resulted in the development of severe steatosis, which can lead to steatohepatitis and/or fibrosis. Troglitazone administration was associated with the development of idiosyncratic acute liver failure and was therefore withdrawn from clinical use [82, 83]. Hepatotoxicity has subsequently been reported in patients taking pioglitazone and rosiglitazone [83, 84]. These data provide support for current clinical practices in which these drugs are avoided or used judiciously in patients with known or suspected liver disease. Further experiments should be initiated to devise a pharmaceutical form appropriate for clinical use.

PPARα agonists are clinically and functionally relevant as fibrate therapeutics against hyperlipidemia and agents for reducing the complications of peripheral vascular disease in diabetic patients [85]. Despite their potentially beneficial roles, PPARα agonists should be used judiciously. Short-term administration in humans (1–10 days) would be unlikely to produce permanent genotoxic effects. However, long-term exposure to these drugs, which would be required to reduce hepatic steatosis, can result in oxidative DNA damage, among other effects [86–90] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Clinical application of strategies that regulate PPARs. Angiotensin: Ang; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: PPARs; ischemic preconditioning: PC; retinol binding protein: RBP4; thiazolidinediones: TZDs.

Further studies will also be required to elucidate whether growth factors, Ang II blockers, or RBP4 may be safer protective pharmacologic strategies for regulating PPAR in hepatic I/R injury in clinical practice (Figure 4). Nevertheless, none of the aforementioned strategies is specific for PPAR.

To avoid the potential side effects of PPAR agonists, strategies that regulate PPARα, such as the induction of PC could be of clinical interest. PC is an adaptive mechanism that consists of a brief period of I/R, resulting in marked resistance in the liver, prior to a subsequent prolonged ischemic stress. Our successes regarding the efficacy of PC in nonsteatotic and steatotic livers undergoing warm ischemia (associated with PH) and liver transplantation [1, 2, 14, 91–93] have resulted in the clinical application of PC.

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of PC in the resection of steatotic and nonsteatotic livers in clinical practice [94–96]. In such studies, the authors primarily performed liver resection via a continuous Pringle maneuver. However, other data indicate that PC does not improve postoperative liver function and does not affect morbidity or mortality after hepatectomy under vascular exclusion of the liver with the preservation of caval flow [97, 98]. The discrepancy between these differential effects of PC during hepatic resection might have arisen from the absence of back flow perfusion of the liver during vascular exclusion compared with that during the Pringle maneuver, which involves interruptions only to the inflow to the liver. In addition, the ischemic period used by Azoulay et al. [97] was longer (10 min on average) that that used by Clavien et al. [94]. All of these could explain, at least partially, the different effectiveness of PC in the clinical practice of liver surgery.

In the past decade, serious efforts have commenced to translate some of the robust benefits of PC against ischemia reperfusion to liver transplantation in clinical practice. It is fair to conclude that the overall clinical results have been less impressive than the observations in experimental animals. There are different data on the effectiveness of PC in I/R injury associated with liver transplantation [99–102]. However, these differential effects cannot be explained by the use of PC periods that have proved experimentally ineffective or by the clinical use of different cold ischemic times from those evaluated experimentally. However, the reduced proportion of subjects with steatosis enrolled in PC trials and the presence of brain death in clinical liver transplantation, which has thus far been evaluated in experimental studies of liver transplantation, should be considered.

As previously mentioned, the proportion of subjects with steatosis who have been enrolled in PC trials to date has been small (10%). Thus, in the future, clinical trials must make serious efforts to include a larger proportion of donor with steatotic livers to clarify the effectiveness of PC in liver transplantation in clinical practice. The benefits of PC are more likely to become clinically meaningful in patient groups with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality following PH, that is, in patients with hepatic steatosis and cirrhosis. In fact, in the largest prospective randomized study of PC in PH, Clavien et al. [94, 103] demostrated that PC was more effective in reducing reperfusion injury in patients with steatotic livers. Furthermore, Li et al. [104] reported that PC decreased the risk of hepatic insufficiency and shortened the hospital stay in patients with cirrhosis who underwent PH. There is the remote possibility that PC may not be effective in the context of brain death. Deceased organ donors have hemodynamic instability with decreased mean arterial pressure, portal venous, and hepatic tissue blood flow. Furthermore, brain death induces a multifaceted, intense systemic inflammatory response that is manifested in many organs, including the liver. It is very likely that such a framework of inflammatory response, well entrenched before the induction of PC, would interact with the various mechanistic aspects of PC and modulate the eventual PC response. To our knowledge, there are no studies of PC in the livers in brain-dead animals. Additional experimental studies of PC of the liver and other organs in brain-dead animals are needed to fill the knowledge gaps. The clinical observations suggest that PC alone may be insufficient to provide easily demonstrable clinical benefits in the presence of brain death. In that context, PC may be more effective when combined with physical, chemical, and pharmacological PC methods. Such experimental investigations could address an important clinical problem in liver transplantation, as more than 80% of livers used for transplantation are taken from cadaveric donors and approximately 20% of all brain-dead donors have a mild-to-moderate hepatic steatosis [105].

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

The use of experimental models has contributed to a better understanding of the multifaceted roles of PPARs. Strategies based on PPAR regulation have the potential to improve the postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing hepatic resections and to increase the number of organs suitable for transplantation, as these strategies may improve the outcomes of patients receiving marginal grafts that would not otherwise have been transplanted, leading to new possibilities for small steatotic liver transplants. Before a complete definition of a successful therapeutic strategy based on PPAR regulation is formed, several additional points need to be addressed. Comparative studies of the roles of different PPAR isoforms in hepatic I/R are required. We recently mapped the effects of PPAR on the pathways involved in the inflammatory process and lipid metabolism, and the effects of PPAR differ according the experimental model used. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting PPAR regulation also differ according to the surgical procedure. Moreover, the response of different types of liver to PPAR stimulation might differ and involve different signal transduction pathways that are at present marginally understood. Further research is required to select drugs that regulate PPAR with minimal side effects and optimize such potential treatments (e.g., dose and pharmacokinetics) before being translated into treatments for human disease. Pharmacological strategies that specifically regulate PPAR including fibrates and TZDs might be inappropriate for clinical liver surgery due to their potential side effects. Conversely, surgical strategies such as PC have been applied in clinical surgery; however, these strategies do not exert their effects exclusively on PPAR, as they affect multiple aspects of I/R injury. Only a full appraisal of the role of PPAR in hepatic I/R and studies on the structure of this transcription factor will permit the design of new protective strategies for clinical liver surgery based on the specific regulation of PPAR without adverse effects.

Financial Support

This research was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Project Grant BFU2009-07410) Madrid, Spain; the ACC1Ó (Project Grant VALTEC08-2-0033) Barcelona, Spain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bioscience Writers for revising the English text. M. Mendes-Braz is in receipt of a fellowship from CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazilia, Brasília. M. B. Jiménez-Castro is in receipt of a fellowship from SETH Foundation (Sociedad Española de Transplante Hepático), Spain.

References

- 1.Massip-salcedo M, Roselló-Catafau J, Prieto J, Avíla MA, Peralta C. The response of the hepatocyte to ischemia. Liver International. 2007;27(1):6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casillas-Ramírez A, Mosbah IB, Ramalho F, Roselló-Catafau J, Peralta C. Past and future approaches to ischemia-reperfusion lesion associated with liver transplantation. Life Sciences. 2006;79(20):1881–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selzner M, Clavien PA. Fatty liver in liver transplantation and surgery. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2001;21(1):105–113. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peralta C, Roselló-Catafau J. The future of fatty livers. Journal of Hepatology. 2004;41(1):149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busuttil RW, Tanaka K. The utility of marginal donors in liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation. 2003;9(7):651–663. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuboki S, Shin T, Huber N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ protects against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Hepatology. 2008;47(1):215–224. doi: 10.1002/hep.21963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akahori T, Sho M, Hamada K, et al. Importance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Journal of Hepatology. 2007;47(6):784–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tailleux A, Wouters K, Staels B. Roles of PPARs in NAFLD: potential therapeutic targets. Biochimia et Biophysica Acta. 2012;1821(5):809–818. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boelsterli UA, Bedoucha M. Toxicological consequences of altered peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) expression in the liver: Insights from models of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;63(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(6):2111–2117. doi: 10.1172/JCI57132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yessoufou A, Wahli W. Multifaceted roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) at the cellular and whole organism levels. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2010;140:w13071–w13080. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straus DS, Glass CK. Anti-inflammatory actions of PPAR ligands: new insights on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends in Immunology. 2007;28(12):551–558. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massip-Salcedo M, Zaouali MA, Padrissa-Altés S, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α inhibits the injurious effects of adiponectin in rat steatotic liver undergoing ischemia-reperfusion. Hepatology. 2008;47(2):461–472. doi: 10.1002/hep.21935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casillas-Ramírez A, Alfany-Fernández I, Massip-Salcedo M, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in steatotic liver transplantation. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;338(1):143–153. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.177691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao CY, Jiang LL, Li L, Deng ZJ, Liang BL, Li JM. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ in pathogenesis of experimental fatty liver disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;10(9):1329–1332. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue M, Ohtake T, Motomura W, et al. Increased expression of PPARγ in high fat diet-induced liver steatosis in mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;336(1):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanne B, Dahllöf B, Lindahl C, et al. PPARα and PPARγ regulation of liver and adipose proteins in obese and dyslipidemic rodents. Journal of Proteome Research. 2006;5(8):1850–1859. doi: 10.1021/pr060004o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duval C, Thissen U, Keshtkar S, et al. Adipose tissue dysfunction signals progression of hepatic steatosis towards nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in C57Bl/6 mice. Diabetes. 2010;59(12):3181–3191. doi: 10.2337/db10-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettinelli P, Videla LA. Up-regulation of PPAR-γ mRNA expression in the liver of obese patients: an additional reinforcing lipogenic mechanism to SREBP-1c induction. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(5):1424–1430. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettinelli P, del Pozo T, Araya J, et al. Enhancement in liver SREBP-1c/PPAR-α ratio and steatosis in obese patients: correlations with insulin resistance and n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid depletion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1792(11):1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricote M, Glass CK. PPARs and molecular mechanisms of transrepression. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1771(8):926–935. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willson TM, Lambert MH, Kliewer SA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and metabolic disease. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2001;70:341–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okaya T, Lentsch AB. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α regulates postischemic liver injury. American Journal of Physiology. 2004;286(4):G606–G612. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00191.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu SQ, Li YH, Hu SH, Chen K, Dong LY. Effects of Wy14643 on hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(45):6936–6942. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teoh NC, Williams J, Hartley J, Yu J, McCuskey RS, Farrell GC. Short-term therapy with peroxisome proliferation-activator receptor-alpha agonist Wy-14,643 protects murine fatty liver against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Hepatology. 2010;51(3):996–1006. doi: 10.1002/hep.23420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao W, Connor HD, Lemasters JJ, Mason RP, Thurman RG. Primary nonfunction of fatty livers produced by alcohol is associated with a new, antioxidant-insensitive free radical species. Transplantation. 1995;59(5):674–679. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199503150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheeler MD, Katuna M, Smutney OM, et al. Comparison of the effect of adenoviral delivery of three superoxide dismutase genes against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Human Gene Therapy. 2001;12(18):2167–2177. doi: 10.1089/10430340152710513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zúñiga J, Cancino M, Medina F, et al. N-3 PUFA supplementation triggers PPAR-α activation and PPAR-α/NF-κB interaction: anti-inflammatory implications in liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2011;16(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028502. Article ID e28502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-γ agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391(6662):82–86. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Knethen A, Brune B. PPARγ: an important regulator of monocyte/macrophage function. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2003;51(4):219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramalho FS, Alfany-Fernandez I, Casillas-Ramírez A, et al. Are angiotensin II receptor antagonists useful strategies in steatotic and nonsteatotic livers in conditions of partial hepatectomy under ischemia-reperfusion? Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2009;329(1):130–140. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saidi RF, Chang J, Verb S. The effect of methylprednisolone on warm ischemia-reperfusion injury in the liver. American Journal of Surgery. 2007;193(3):345–347. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2005;12(2):1542–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaouali MA, Padrissa-Altés S, Mosbah IB, et al. Improved rat steatotic and nonsteatotic liver preservation by the addition of epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor-I to University of Wisconsin solution. Liver Transplantation. 2010;16(9):1098–1111. doi: 10.1002/lt.22126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casillas-Ramírez A, Zaouali A, Padrissa-Altés S, et al. Insulin-like growth factor and epidermal growth factor treatment: New approaches to protecting steatotic livers against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Endocrinology. 2009;150(7):3153–3161. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casillas-Ramírez A, Amine-Zaouali M, Massip-Salcedo M, et al. Inhibition of angiotensin II action protects rat steatotic livers against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(4):1256–1266. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816a023c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ip E, Farrell GC, Robertson G, Hall P, Kirsch R, Leclercq I. Central role of PPARα-dependent hepatic lipid turnover in dietary steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2003;38(1):123–132. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ip E, Farrell G, Hall P, Robertson G, Leclercq I. Administration of the potent PPARα agonist, Wy-14,643, reverses nutritional fibrosis and steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;39(5):1286–1296. doi: 10.1002/hep.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagasawa T, Inada Y, Nakano S, et al. Effects of bezafibrate, PPAR pan-agonist, and GW501516, PPARδ agonist, on development of steatohepatitis in mice fed a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;536(1-2):182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zabielski P, Blachnio-Zabielska A, Baranowski M, Zendzian-Piotrowska M, Gorski J. Activation of PPARα by bezafibrate negatively affects de novo synthesis of sphingolipids in regenerating rat liver. Prostaglandins and Other Lipid Mediators. 2010;93(3-4):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka N, Sano K, Horiuchi A, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Aoyama T. Highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid treatment improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2008;42(4):413–418. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815591aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capanni M, Calella F, Biagini MR, et al. Prolonged n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation ameliorates hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;23(8):1143–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spadaro L, Magliocco O, Spampinato D, et al. Effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2008;40(3):194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu FS, Liu S, Chen XM, Huang ZG, Zhang DW. Effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from seal oils on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with hyperlipidemia. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(41):6395–6400. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatzitolios A, Savopoulos C, Lazaraki G, et al. Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids, atorvastatin and orlistat in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with dyslipidemia. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;23(4):131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α mediates the adaptive response to fasting. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103(11):1489–1498. doi: 10.1172/JCI6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson SP, Yoon L, Richard EB, Dunn CS, Cattley RC, Corton JC. Delayed liver regeneration in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α-null mice. Hepatology. 2002;36(3):544–554. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gavrilova O, Haluzik M, Matsusue K, et al. Liver peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma contributes to hepatic steatosis, triglyceride clearance, and regulation of body fat mass. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(36):34268–34276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.García-Ruiz I, Rodríguez-Juan C, Díaz-Sanjuán T, Martínez MÁ, Muñoz-Yagüe T, Solís-Herruzo JA. Effects of rosiglitazone on the liver histology and mitochondrial function in ob/ob mice. Hepatology. 2007;46(2):414–423. doi: 10.1002/hep.21687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turmelle YP, Shikapwashya O, Tu S, Hruz PW, Yan Q, Rudnick DA. Rosiglitazone inhibits mouse liver regeneration. The FASEB Journal. 2006;20(14):2609–2611. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6511fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu S, Matsusue K, Kashireddy P, et al. Adipocyte-specific gene expression and adipogenicsteatosis in the mouse liver due to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ1 (PPARγ1) overexpression. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(1):498–505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Enomoto N, Takei Y, Hirose M, et al. Prevention of ethanol-induced liver injury in rats by an agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, pioglitazone. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;306(3):846–854. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(18):1675–1685. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aoyama T, Ikejima K, Kon K, Okumura K, Arai K, Watanabe S. Pioglitazone promotes survival and prevents hepatic regeneration failure after partial hepatectomy in obese and diabetic KK-Ay mice. Hepatology. 2009;49(5):1636–1644. doi: 10.1002/hep.22828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nan YM, Han F, Kong LB, et al. Adenovirus-mediated peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma overexpression prevents nutritional fibrotic steatohepatitis in mice. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;46(3):358–369. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.525717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsusue K, Haluzik M, Lambert G, et al. Liver-specific disruption of PPARγ in leptin-deficient mice improves fatty liver but aggravates diabetic phenotypes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111(5):737–747. doi: 10.1172/JCI17223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee SST, Pineau T, Drago J, et al. Targeted disruption of the α isoform of the peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15(6):3012–3022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reddy JK. Nonalcoholic steatosis and steatohepatitis III. Peroxisomal β-oxidation, PPARα, and steatohepatitis. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;281(6):G1333–G1339. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.6.G1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clarke SD. Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of gene transcription: a molecular mechanism to improve the metabolic syndrome. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(4):1129–1132. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delarue J, LeFoll C, Corporeau C, Lucas D. N-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids: a nutritional tool to prevent insulin resistance associated to type 2 diabetes and obesity? Reproduction Nutrition Development. 2004;44(3):289–299. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2004033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lombardo YB, Chicco AG. Effects of dietary polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids on dyslipidemia and insulin resistance in rodents and humans. A review. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2006;17(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neschen S, Moore I, Regittnig W, et al. Contrasting effects of fish oil and safflower oil on hepatic peroxisomal and tissue lipid content. American Journal of Physiology. 2002;282(2):E395–E401. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00414.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shteyer E, Liao Y, Muglia LJ, Hruz PW, Rudnick DA. Disruption of hepatic adipogenesis is associated with impaired liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40(6):1322–1332. doi: 10.1002/hep.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ezaki H, Yoshida Y, Saji Y, et al. Delayed liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in adiponectin knockout mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;378(1):68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fernàndez MA, Albor C, Ingelmo-Torres M, et al. Caveolin-1 is essential for liver regeneration. Science. 2006;313(5793):1628–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1130773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walldorf J, Hillebrand C, Aurich H, et al. Propranolol impairs liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in C57Bl/6-mice by transient attenuation of hepatic lipid accumulation and increased apoptosis. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;45(4):468–476. doi: 10.3109/00365520903583848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moran-Salvador E, Lopez-Parra M, Garcia-Alonso V, et al. Role for PPARγ in obesity-induced hepatic steatosis as determined by hepatocyte- and macrophage-specific conditional knockouts. The FASEB Journal. 2011;25(8):2538–2550. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selzner M, Clavien PA. Failure of regeneration of the steatotic rat liver: disruption at two different levels in the regeneration pathway. Hepatology. 2000;31(1):35–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang SQ, Mandal AK, Huang J, Diehl AM. Disrupted signaling and inhibited regeneration in obese mice with fatty livers: implications for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease pathophysiology. Hepatology. 2001;34(4 I):694–706. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leclercq IA, Field J, Farrell GC. Leptin-specific mechanisms for impaired liver regeneration in ob/ob mice after toxic injury. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(5):1451–1464. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamauchi H, Uetsuka K, Okada T, Nakayama H, Doi K. Impaired liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in db/db mice. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2003;54(4):281–286. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.DeAngelis RA, Markiewski MM, Taub R, Lambris JD. A high-fat diet impairs liver regeneration in C57BL/6 mice through overexpression of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα . Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1148–1157. doi: 10.1002/hep.20879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rudnick DA. Trimming the fat from liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1001–1003. doi: 10.1002/hep.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lai HS, Chen WJ. Alterations of remnant liver carnitine palmitoyltransferase I activity and serum carnitine concentration after partial hepatectomy in rats. Journal of Surgical Research. 1995;59(6):754–758. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1995.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aoyama T, Peters JM, Iritani N, et al. Altered constitutive expression of fatty acid-metabolizing enzymes in mice lacking the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(10):5678–5684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farrell GC. Probing Prometheus: fat fueling the fire? Hepatology. 2004;40(6):1252–1255. doi: 10.1002/hep.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chinetti G, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): nuclear receptors at the crossroads between lipid metabolism and inflammation. Inflammation Research. 2000;49(10):497–505. doi: 10.1007/s000110050622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsai CY, Lin YS, Yeh TS, et al. Disrupted hepatic adiponectin signaling impairs liver regeneration of steatotic rats. Chang Gung Medical Journal. 2011;34(3):248–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schoonjans K, Auwerx J. Thiazolidinediones: an update. The Lancet. 2000;355(9208):1008–1010. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yki-Jarvinen H. Thiazolidinediones. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(11):1106–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Plutzky J. The potential role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors on inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2003;92(4):34J–41J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00614-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kohlroser J, Mathai J, Reichheld J, Banner BF, Bonkovsky HL. Hepatotoxicity due to troglitazone: report of two cases and review of adverse events reported to the United States food and drug administration. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95(1):272–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tolman KG. Thiazolidinedione hepatotoxicity: a class effect? International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2000;(113):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marcy TR, Britton ML, Blevins SM. Second-generation thiazolidinediones and hepatotoxicity. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2004;38(9):1419–1423. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bulhak AA, Jung C, Ostenson CG, Lundberg JO, Sjöquist PO, Pernow J. PPAR-α activation protects the type 2 diabetic myocardium against ischemia-reperfusion injury: involvement of the PI3-kinase/Akt and NO pathway. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;296(3):H719–H727. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00394.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Woods CG, Burns AM, Bradford BU, et al. WY-14,643-induced cell proliferation and oxidative stress in mouse liver are independent of NADPH oxidase. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;98(2):366–374. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lovett-Racke AE, Hussain RZ, Northrop S, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α agonists as therapy for autoimmune disease. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(9):5790–5798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rusyn I, Asakura S, Pachkowski B, et al. Expression of base excisionDNArepair genes is a sensitive biomarker for in vivo detection of chemical-induced chronic oxidative stress: identification of the molecular marker source of radicals responsible for DNA damage by peroxisome proliferators. Cancer Research. 2004;64(3):1050–1057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li Y, Leung LK, Glauert HP, Spear BT. Treatment of rats with the peroxisome proliferator ciprofibrate results in increased liver NF-κB activity. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17(11):2305–2309. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.11.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rusyn I, Yamashina S, Segal BH, et al. Oxidants from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase are involved in triggering cell proliferation in the liver due to peroxisome proliferators. Cancer Research. 2000;60(17):4798–4803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Serafín A, Roselló-Catafau J, Prats N, Gelpí E, Rodés J, Peralta C. Ischemic preconditioning affects interleukin release in fatty livers of rats undergoing ischemia/reperfusion. Hepatology. 2004;39(3):688–698. doi: 10.1002/hep.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elias-Miró M, Massip-Salcedo M, Jimenez-Castro M, Peralta C. Does adiponectin benefit steatotic liver transplantation? Liver Transplantation. 2011;17(9):993–1004. doi: 10.1002/lt.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jimenez-Castro MB, Casillas-Ramírez A, Massip-Salcedo M, et al. Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in rat steatotic liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation. 2011;17(9):1099–1110. doi: 10.1002/lt.22359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Clavien PA, Selzner M, Rudiger HA, et al. A prospective randomized study in 100 consecutive patients undergoing major liver resection with versus without ischemic preconditioning. Annals of Surgery. 2003;238(6):843–852. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098620.27623.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Choukèr A, Martignoni A, Schauer R, et al. Beneficial effects of ischemic preconditioning in patients undergoing hepatectomy: the role of neutrophils. Archives of Surgery. 2005;140(2):129–136. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Vellone M, et al. Pedicle clamping with ischemic preconditioning in liver resection. Liver Transplantation. 2004;10(2) supplement 1:S53–S57. doi: 10.1002/lt.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Azoulay D, Lucidi V, Andreani P, et al. Ischemic preconditioning for major liver resection under vascular exclusion of the liver preserving the caval flow: a randomized prospective study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2006;202(2):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rahbari NN, Wente MN, Schemmer P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of portal triad clamping on outcome after hepatic resection. British Journal of Surgery. 2008;95(4):424–432. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Azoulay D, Del Gaudio M, Andreani P, et al. Effects of 10 minutes of ischemic preconditioning of the cadaveric liver on the graft’s preservation and function. Annals of Surgery. 2005;242(1):133–139. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167848.96692.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cescon M, Grazi GL, Grassi A, et al. Effect of ischemic preconditioning in whole liver transplantation from deceased donors. A pilot study. Liver Transplantation. 2006;12(4):628–635. doi: 10.1002/lt.20640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Amador A, Grande L, Martí J, et al. Ischemic pre-conditioning in deceased donor liver transplantation: a prospective randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Transplantation. 2007;7(9):2180–2189. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Koneru B, Shareef A, Dikdan G, et al. The ischemic preconditioning paradox in deceased donor liver transplantation—evidence from a prospective randomized single blind clinical trial. American Journal of Transplantation. 2007;7(12):2788–2796. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Clavien PA, Yadav S, Sindram D, Bentley RC. Protective effects of ischemic preconditioning for liver resection performed under inflow occlusion in humans. Annals of Surgery. 2000;232(2):155–162. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li SQ, Liang LJ, Huang JF, Li Z. Ischemic preconditioning protects liver from hepatectomy under hepatic inflow occlusion for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with cirrhosis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;10(17):2580–2584. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yamagami K, Hutter J, Yamamoto Y, et al. Synergistic effects of brain death and liver steatosis on the hepatic microcirculation. Transplantation. 2005;80(4):500–505. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000167723.46580.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]