Abstract

Cell migration participates in a variety of physiological and pathological processes such as embryonic development, cancer metastasis, blood vessel formation and remoulding, tissue regeneration, immune surveillance and inflammation. The cells specifically migrate to destiny sites induced by the gradually varying concentration (gradient) of soluble signal factors and the ligands bound with the extracellular matrix in the body during a wound healing process. Therefore, regulation of the cell migration behaviours is of paramount importance in regenerative medicine. One important way is to create a microenvironment that mimics the in vivo cellular and tissue complexity by incorporating physical, chemical and biological signal gradients into engineered biomaterials. In this review, the gradients existing in vivo and their influences on cell migration are briefly described. Recent developments in the fabrication of gradient biomaterials for controlling cellular behaviours, especially the cell migration, are summarized, highlighting the importance of the intrinsic driving mechanism for tissue regeneration and the design principle of complicated and advanced tissue regenerative materials. The potential uses of the gradient biomaterials in regenerative medicine are introduced. The current and future trends in gradient biomaterials and programmed cell migration in terms of the long-term goals of tissue regeneration are prospected.

Keywords: regenerative medicine, biomaterials, gradient, cell migration, biointerfaces

1. Introduction

Regenerative medicine is a process of replacing or regenerating human cells, tissues or organs to restore or establish their normal functions. One important approach is inductive tissue regeneration, which is defined as a technology to repair the tissues or organs using a bioactive matrix in situ. In this way, regeneration of tissues or organs can be achieved by recruitment of nearby matured cells and guided differentiation of stem cells [1]. In this process, one of the most important issues is to build up an in vivo microenvironment, the so-called niche, which can provide spatio-temporal signals to guide the adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis of cells at right locations and timing [2].

In order to understand the tissue regeneration process and thereby provide guidance principles for designing biomaterials, it is of paramount importance to study the cell migration behaviour in the presence of physical, chemical and biological cues. Cells in a living body migrate in response to gradients of stimuli such as soluble chemoattractants (chemotaxis), surface-attached molecules (haptotaxis) and biophysical contact cues (durotaxis or mechanotaxis) [3,4]. Ramón & Cajal [5] first proposed that gradients of attractive molecules could guide growing axons to their targets. Since then, in vivo gradients of chemical signals have been proved to exist and their roles in guiding the translocation of cells have been widely recognized.

The introduction of so-called ‘gradient materials’, i.e. spatio-temporal gradients, offers a means to serve as an in vitro model, enabling the studies of cell behaviours in a complex but precisely defined microenvironment. Over the past few decades, various technologies have been developed to create spatio-temporal gradients and complex biomaterials [6,7]. The gradient materials have been used to study the cellular responses in terms of cell adhesion, distribution and alignment [8]. Recently, cell migration on gradient materials [9] and their potential applications in tissue regeneration [10,11] have attracted more and more attention.

In this review, we focus on the role of the gradient materials in guiding cell migration. First, specific biological examples of gradients existing in vivo and their influences on cell migration will be summarized. Technologies for preparing the gradient materials will be introduced, followed by the migration behaviours of cells on the gradient materials. Finally, the review concludes with current challenges and future prospects. Since the research of gradient materials is in the status of rapid development and continues in a divergent genre, our purpose is not to include all publications in this review article but to give a brief overview of the state-of-the-art and future perspectives in this field.

2. Gradients in vivo and their influences on cell migration

Cell migration in vivo is a very significant process in both physiological and pathological aspects. During embryonic development in mammals, cells migrate beneath the ectoderm to create a different germ layer. This targeted cell translocation is required for proper tissue formation [12]. Cell migration is also prominent in numerous processes in adults, such as morphogenesis, angiogenesis, wound healing, immune response and tumour metastasis [13,14]. For example, when a wound occurs, the inflammatory cells and fibroblasts invade into the temporarily formed clots. Meanwhile, the epidermal cells proliferate and migrate to cover the surface [13]. In metastasis, tumour cells detach from the original tumour, invade into the blood and lymphatic system and subsequently settle down in a new site. Gradients existing in vivo provide a driving force to complete multiple biological activities by either accelerating or slowing down the cell migration.

2.1. The biological process of cell migration

The migration mechanisms have been extensively studied in vitro. The newly developed fluorescent-tagging technology can visualize directly cell migration in vivo [15]. Cell migration is a complex process requiring the cooperation of cytoskeleton, membrane and signalling systems. Responding to the external topographic or chemical stimuli, cells protrude their leading edge (figure 1) [16]. The directional extension of the active membrane, including both lamellipodia (sheet-like protrusions) and filopodia (spike-like protrusions), brings attachment and thus the traction force to the substrate, resulting in a counter-force on the cell to promote cell migration [17]. The contraction of cytoskeleton filaments pulls the cell body towards the leading edge, with a consequent release of adhesion at the rear to allow the tail to retract and the cell to move forward. All these steps involve the assembly and disassembly of the cytoskeleton filaments, especially actin filaments. Herein, the moderate adhesion strength provided by the supporting matrix is essential for dynamic cell protrusion and contraction [18].

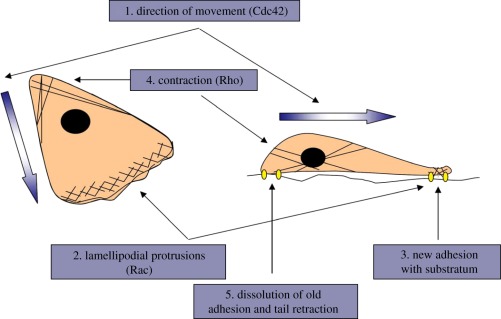

Figure 1.

A migrating cell seen from the top (left) and side (right). A migrating cell needs to perform a coordinated series of steps to move. Cdc42 regulates the direction of migration, Rac induces membrane protrusion at the front of the cell through stimulation of actin polymerization and integrin adhesion complexes and Rho promotes contraction in the cell body and at the rear [16].

The cell migration process also involves the spatio-temporal transition of intracellular signalling, such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and the Rho family of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) [19–22]. Rho family GTPases, including Cdc42, Rac and Rho, act as molecular switches of actin polymerization, actomyosin contraction and cell mobility. Cdc42 and Rac regulate actin polymerization and membrane protrusion while Rho generates the contraction and retraction forces required in the cell body and at the rear [23]. MAPKs, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, can promote cell migration by regulating actin dynamics. For example, ERK1 and ERK2 can phosphorylate myosin light chain kinase and increase myosin light chain phosphorylation to enhance cell migration [24–26]. In addition, many downstream signal molecules participate in the migration process. For example, the Ser/Thr kinase p65PAK controls focal adhesion turnover. It is important because the integrin adhesion complexes should dynamically change, allowing the cells to adhere and pass [27].

2.2. Gradients in vivo

Cells in the living body migrate in response to diverse gradients of stimuli. They are surrounded by the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is a complex network consisting of proteins, polysaccharides and signalling molecules. Physical cues such as matrix pore size and stiffness as well as the concentration of signalling molecules are the main guiding cues for cell migration in vivo, inducing cell polarity and thus controlling the migration rate and direction.

2.2.1. Physical gradients

Physical gradients are defined here as the gradual change in a physical property such as porosity, stiffness and topology. Physical gradients occur naturally in bone structure. The dense cortical bone is located at the centre, which is surrounded by a low-density ‘trabecular’ bone. The pore size increases from inside to outside. Structures like this can provide excellent permeability as well as desired mechanical support [28]. Particularly, the strength (especially compressive strength) is inversely dependent on the porosity and the pore volume [29]. Therefore, the bimodal structure of bone (cortical and cancellous) yields the gradient of mechanical properties in the natural bone. Bone stiffness and elasticity can also be determined by variability in mineralization or mineral density, cell type and cytokines gradient features [30]. The compression strength differs from 133 MPa in the mid-femur to 6.8 MPa in the proximal femur, while the modulus of elasticity decreases from 17 to 0.441 GPa [31]. Teeth also contain gradients in composition and mineral density, leading to gradients in mechanical properties [32].

2.2.2. Chemical gradients

There are two kinds of chemical gradients existing in the living body. One is matrix-integrated biomolecules, including chemokines, hormones, proteins (such as fibronectin (Fn), vitronectin, laminin and collagen) and growth factors (such as the epidermal growth factor (EGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and vascular epidermal growth factor (VEGF)). Their concentrations can initiate multiple intracellular signalling pathways through binding to receptors on the cell surface, resulting in the regulation of cell functions. In the vertebrate gastrula of zebrafish, there is a ventral to dorsal gradient of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) activity, which is established partly by secretion of BMP antagonists from the dorsal gastrula organizer [33–35]. During the period of tibial Ti1 pioneer neuron outgrowth in the grasshopper limb bud, semaphoring Sema 2a is expressed in a gradient. These gradients are exponential with the same absolute concentration, but differ in steepness [36]. The sensing of fractional variation of Sema 2a concentration provides critical guidance information to the pathfinding growth cone. In the epithelium of the small intestine, laminin-2 expression decreases from the base of the villus to the top, while the expression of laminin-1 increases. Stem cells proliferate and undergo differentiation while migrating upward to the tip of the villus, suggesting that the gradients of surface-bound biomolecules manipulate a lot of biological processes in vivo. When these signalling molecules are released by the matrix, the second category of gradients, i.e. the gradients of soluble biomolecules, is formed through diffusion and convection (larger molecules) [37,38]. The cell responses to the gradients depend on the diffusion speed and distance of these signalling molecules [39]. These two kinds of gradients coordinate with each other to complete biological activities. For example, during vasculogenesis or angiogenesis, the soluble VEGF gradient increases the vessel calibre, while the gradient of matrix-bound VEGF promotes the sprouting of vessel branches [40].

2.3. Possible mechanism of gradient-dominated cell migration

In nature, an object always travels randomly in an environment without an asymmetric cue, which has been recognized as Brownian movement. In an anisotropic system, a driving force is imposed on the object owing to the asymmetric interactions within the surrounding environment. Previous researches recognize a directional transport of liquid and particles on the gradients of surface energy [41]. Thus, the gradients are sometimes known as ‘surface-bound engines’ since the motion is driven by the imbalance of object–substrate interactions [7].

For cells, the first response to gradient is to polarize, by redistributing chemosensory signalling receptors [42–44]. Chan & Yousaf [45] reported that when the cells were seeded on a low-density region of a ligand gradient, their organelles reoriented and positioned towards the side of higher ligand density. Arnold et al. [46] and Hirschfeld-Warneken et al. [47] used a defined Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) gradient to modulate spatial distribution of integrin transmembrane receptors on the cell membrane, leading to cell polarization and, in a further step, migration. When cellular polarization persists in one direction owing to the external gradient signalling, cell migration happens in succession. Another interpretation for cell migration induced by the gradient is attributed to the adhesiveness, which is influenced by the shifts of chemical and physical properties of the underlying substrate. Cells attach to the substrate more tightly at one end, and this imbalance in adhesive force leads to movement towards the direction of increasing adhesiveness. However, cell migration is not a long-lasting process without interval. The rear of a cell contracts to diminish the extent of cellular polarization, and the movement is paused until the cell polarizes again [42,43]. Smith et al. [48] found that the cells moved faster on a gradient with a larger slope, but showed no difference in cell polarization. So the increase in speed is thought to be attributed to the higher frequency of cellular polarization, gradient recognition or more stable polarization morphology.

3. Methods for preparation of gradient biomaterials

So far, two categories of techniques, i.e. ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’, have been developed to produce gradient surfaces. The former technique modifies the surface gradually via external sources such as light, electron, plasma, etching solution and so on [49] to change the properties of a surface. The latter one constructs patterns by continuously introducing building blocks on the surface, for example, silane, thiol and macromolecules, without changing the bulk properties [50]. Besides these technologies, which are initially designed for the modification of the planner surface, another category of technologies has been developed to construct gradients in three-dimensional matrices.

3.1. Top-down technologies

The top-down approach is mostly used to introduce active sites on an inert surface, which is feasible for further functionalization. For the inert surfaces without reactive groups, such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polytetrafluoroethylene and polyesters, modifications can be performed by using high-energy sources, including plasma, corona and ultra-violet (UV) light (figure 2). They provide a destructive process for generating various functionalities. In this way, the change of chemical compositions is usually accompanied with a slight alternation of physical roughness. The variation of gradient chemistry is made through progressively altering the exposure time or the power of the apparatus on one single sample.

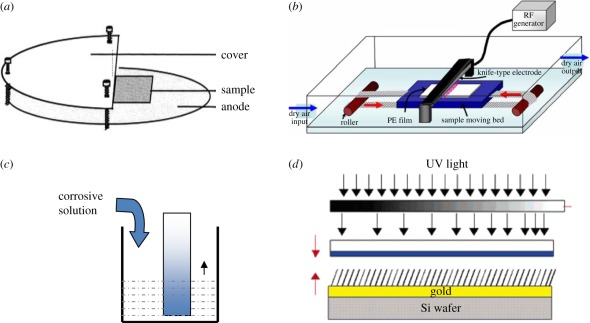

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic (side view) of the glow-discharge reactor chamber, with the electrodes, sample cover and sample position [51]. (b) Schematic of the apparatus for preparation of a gradient on PE surfaces by corona discharge [52]. (c) Scheme of the preparation process of the gradient by a chemical degradation method. (d) Remote photocatalytic oxidation of a thiol self-assembled monolayer (SAM) under a gradient of UV illumination [53].

3.1.1. Plasma

The plasma modifies a substrate by bombarding the surface with high-energy particulates including electrons, atoms, ions, neutral molecules and radicals. The etching extent of a surface is gradually weakened by partly keeping off the particles. Spijker et al. [51] generated a gradient surface by positioning an aluminium shield over the sample. The slope of the resulting gradient could be conveniently tuned by changing the distance between the cover and the sample. Mangindaan et al. [54] created a wettability gradient on a PP film by plasma treatment under a mask that had a 2 mm gap to the sample. Various functional groups such as amino groups, carboxyl groups, hydroxyl groups and sulphonic acid groups can be introduced onto the substrate by applying nitrogen, ammonia, oxygen and sulphur dioxide plasma, respectively [55,56]. As a result, the surfaces become reactive and the wettability is largely improved. On the contrary, the plasma of a fluoride-bearing gas can impose fluorine into the materials and increase the hydrophobicity. Gradients can also be created by depositing polymeric precursors on the surface under a shield during plasma polymerization in a similar apparatus [57].

3.1.2. Corona discharge

Corona discharge treatment is a relatively simple and cheap technology to generate gradient surfaces, as the samples are treated in air rather than in a vacuum during plasma treatment. Lee and co-workers used this technology to create gradient surfaces [52,58–61]. The polymer sheet is placed beneath a knife-type electrode that is connected to a radio-frequency generator. Carbon radicals are produced on the polymer surfaces, forming hydroperoxides that can be further decomposed into polar oxygen-based functionalities such as the hydroxyl group, ether, ketone, aldehyde, carboxylic acid and carboxylic ester [59]. By gradually increasing power while delivering the sample with a motorized drive, gradients with an increasing density of active groups can be produced [62]. The radicals also can serve as initiators to trigger the surface-initiated grafting polymerization as well as active sites to bind biomacromolecules [63,64].

3.1.3. Ultra-violet irradiation

Using UV irradiation, peroxides can be generated on the surfaces by a radical-based photo-oxidation mechanism [65]. Li et al. [66,67] produced a gradient with an increasing density of carboxyl groups by continuously moving the photo mask under a UV lamp. This process has many advantages. For instance, the photoreaction is efficient and occurs in a single step without specific reaction conditions except light. Besides, simultaneous multicomponent immobilization is possible. Another method using light to prepare gradient surfaces is photolithography [41,53,68]. The substrate is firstly covered with a self-assembled monolayer (SAM), which usually is thiol or silane, and then the organic layer is degraded by UV irradiation. Blondiaux et al. [53] developed a technique that combined a gradually changed greyscale mask with titanium dioxide (TiO2) remote photocatalytic lithography. The TiO2 layer is placed under the photomask, and the region affected by the UV irradiation produced radicals, which diffuse vertically and thus locally degrade the organic SAM on the gold surface underneath. As a result of using a greyscale mask, the thiol layer is oxidized gradually and a chemical gradient is created. The shape and length of the gradients can be conveniently controlled by using different masks.

3.1.4. Chemical degradation

This method is normally applied to degradable polymers such as polyesters or polymers with degradable side chains. Zhu et al. developed an aminolysis technology to introduce amino groups on the surface of polyesters, which act as active sites to immobilize biomacromolecules [69–71] or surface-initiated grafting polymerizations [72]. Using this method, polymers are degraded progressively by continuous immersion into the reactive solution or addition of the reactive solution into a vessel containing the films [73]. Tan and co-workers [74,75] used this technology to construct a density gradient of amino groups on a poly(l-lactic acid) (PLLA) film by continuous injection of the reactive solution into a container via a microinjection pump. Besides polymers, the chemical etching method can also be applied to modulate the composition and structure of polyelectrolyte multilayers that are assembled by alternative adsorption of polycations and polyanions via electrostatic attraction. Generally, post-treatment of the multilayers in a salt solution with a critical high ionic strength will redistribute the charge and multilayer structures, and soften, swell and even dissolve the polyelectrolyte multilayers [76]. The chemical composition and the related structure of the etched multilayers are correlated with salt concentrations, providing a feasible methodology to generate gradient multilayers. Kunzler et al. [77] prepared a polymer surface with a roughness gradient via a replica of the aluminium template by gradual immersion into a chemical polishing solution, which preferentially removes features with a small radius of curvature as a function of time.

However, the top-down technologies in general are limited to the types of functional surfaces and unsuitable to process surfaces with unstable biomacromolecules such as ECM proteins and growth factors, and thus may not be able to fulfil the complicated requirements of modulating cell responses. Thus, recently, the bottom-up methods are more widely used or adopted to further functionalize the surfaces after introduction of active sites on inert surfaces by the top-down approaches.

3.2. Bottom-up technologies

The bottom-up technology has no limitations on the species of functional molecules introduced onto surfaces with an adjustable grafting density, chain length and mobility. By changing these parameters, the surface properties can be gradually switched from hydrophilic to hydrophobic [78], from soft to rigid and from antifouling to cell adhesive [79]. The gradient surfaces can be generated by time and spatially controlled reactions or by reactions in a gradient concentration of molecules (figure 3).

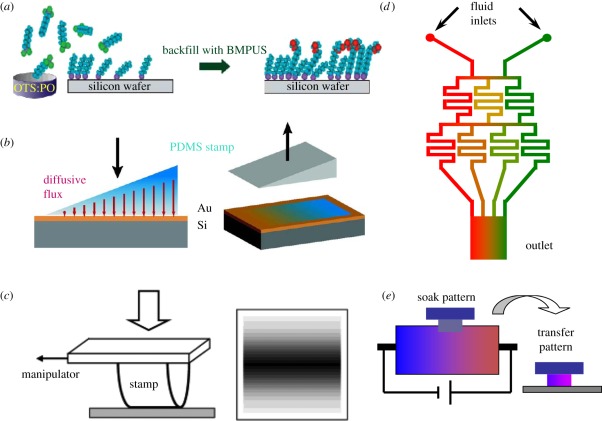

Figure 3.

(a) A molecular gradient of n-octyl trichlorosilane is formed on a surface by a vapour deposition technique. As the silane evaporates, it diffuses in the vapour phase and generates a concentration gradient along the silica substrate. A silane self-assembled monolayer (SAM) is formed when impinging on the substrate, followed by backfill of the unreacted regions with (11-(2-bromo-2-methyl)propionyloxy)undecyltrichlorosilane (BMPUS) [58]. (b) Thiol diffuses into the stamp from an ink pad. It leaves the stamp because of adsorption to the gold surface and creates a partially covered surface [80]. (c) Symmetrical lateral gradients are generated using hemicylindrical stamps. The contact area increases under increased compression. The darker areas indicate the more hydrophobic region where the contact time is longer. The sketch is not to scale [81]. (d) Schematic of a representative gradient-generating microfluidic network. Solutions containing different chemicals are introduced from the top inlets and allowed to flow through the network. When all the branches are recombined, a concentration gradient is established across the outlet channel (modified from Dertinger et al. [82]). (e) A solution of poly-d-lysine is used as the soaking solution. An appropriate voltage is applied between Ag/AgCl electrodes. After the system comes to equilibrium, the stamp is carefully immersed and soaked for 10 min. The stamp is then dried with nitrogen and contacts the surfaces under pressure in order to achieve pattern transfer (modified from Venkateswar et al. [83]).

3.2.1. Infusion

By gradually elevating or lowering the solution level, surfaces can be decorated with an organic monolayer with a gradient pattern [84,85]. The method is so simple and convenient that neither special instruments nor rigorous conditions are required. Furthermore, it is feasible to generate gradients of a variety of chemical functionalities on the millimetre–centimetre scale. By means of controlling the injection speed at a set value, the position on the gradient corresponds directly to the immersion time. The slope of the gradient also can be tuned by adjusting the injection speed. The concentration of molecules or the length of polymers on the gradient decreases linearly with its maximum at the bottom end, which reacts for the longest time. Yu et al. [86] fabricated a gradient from superhydrophobicity to superhydrophilicity by slowly adding an HS(CH2)11CH3 solution to a container holding the gold substrate and then backfilling HS(CH2)10CH2OH. The slope of the gradient is easily tuned since a higher addition speed will make a smaller slope [87]. In a further step, the gradients can be backfilled either in a contrary direction (a head-to-tail method) or by fully immersing it into the complementary solution (a full-immersion method). Obviously, the head-to-tail method produces a steeper gradient [88]. Also, the slopes and the lengths of the gradients can be tailored by changing the feeding concentration and immersion time [89].

3.2.2. Diffusion

The diffusion and transportation of mass can be mediated by solution, vapour or gels. The pattern of a gradient is produced by imprinting molecules onto a surface. Chaudhury & Whitesides [90] evaporated silane molecules, which were preferentially deposited on the substrate end that was closer to the source, and an organosilane density gradient was generated. The breadth and steepness of the gradient can be easily tuned by varying the diffusion time, gas type, humidity and temperature [91–93]. Mougin & Liedberg prepared thiol gradients by diffusing through a gel matrix, and then transferred the molecular gradients to gold surfaces [94,95]. However, there is a common problem called ‘fingering’ when two diffusion streams meet. As a result, an inhomogeneity will inevitably exist in the direction perpendicular to the gradient [79].

3.2.3. Microcontact printing

The contact printing, developed by Whitesides and his co-workers, has been widely used for generating SAMs for its versatility and high accuracy in the nanoscale. Recently, a series of technologies have been developed based on microcontact printing (µCP), such as decal transfer microlithography [96], nanotransfer printing [94] and metal transfer printing [97,98]. Jeon et al. [99] found that the surface coverage of octadecyltrichlorosilane (OTS) was augmented by prolongation of contact time. Based on Jeon's finding, Choi developed a method to generate a gradient by varying the contact duration time. Gradual or stepwise increase in the pressure on the half-ball re-shaped the elastic stamp, leading to the increase in contact area and decrease in contact time from the centre to the edge. Consequently, the concentration gradients of OTS are fabricated and the gradient length is tuned by the radius and curvature of the silicone stamp [81]. Kraus et al. [80] produced a chemical gradient by a method of mass-transfer µCP, in which the ink mass transported to the substrate is controlled by the thickness of the stamp. Although the patterns generated by µCP are complex and facile, the µCP technologies are limited to a planar surface [100].

3.2.4. Microfluidic lithography

The microfluidic system offers a simple, versatile way of generating compositional and precisely defined gradients of growth factors, ECM proteins, enzymes, drugs and other types of biologically relevant molecules. Additionally, by designing the microchannel system, the slope and shape (linear/nonlinear) of the gradients are easily controlled [82,101]. Gunawan et al. [12] injected laminin and collagen solutions into a microfluidic system where they spit and mix while flowing through the channels. The streams containing the highest concentration of laminin or collagen are in the farthest channel, where they do not mix with each other. Finally, the streams gather in the main channel and a gradient with laminin and collagen in the converse direction is formed. The microfluidic system also can be used to generate physical gradients. For example, a gradient of roughness is fabricated on a silicon wafer after etching by a hydrogen fluoride gradient that is created via the microfluidic lithography method. By combining solutions of unifunctional monomers and bis-functional monomers in the microchannels and exposing to UV light, a gradient of surface modulus is created too [102]. The two-dimensional channel system limits itself to simple and continuous patterns. To overcome this limitation, a three-dimensional microfluidic technique is developed using several layers of interconnecting channels [100]. It gives sufficient versatility for creating complex and discontinuous constructs and incorporates multiple biomolecules on a planar surface. There are many advantages of microfluidic processes, such as a small dimension of applications, manipulable fluidic volume and low power requirement [103].

3.2.5. Electrochemical method

The isoelectric focusing technology (IEF) has been developed for several decades. In this approach, a concentration gradient of charged molecules can be formed and then transferred to a desired substrate [104]. In the IEF technique, the ampholytes migrate in the solution as a result of the electric field. For instance, the positively charged polylysine (PLL) accumulates closest to the cathode and forms a concentration gradient. A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp is then soaked into the solution, followed by pressing it onto a substrate to obtain the PLL gradient. This method can be applied to a multitude of polyelectrolytes including proteins, peptides and polysaccharides. The slope of the gradients can be adjusted by both the external electrical field and the pH value of the environment, which influences the charge property of the molecules. However, the process of soaking the stamp should be treated lightly to avoid disturbance of the solution [83].

The gradients have also been produced using electrical techniques based on an oxidation–reduction reaction of thiol adsorbed on a gold surface. By applying an external electric field, the thiol is reduced and detached from the substrate in the region near the cathode, whereas it is oxidized and adsorbed onto the substrate in the region near the anode [45,105].

3.3. Three-dimensional gradient generation technologies

The gradients in a three-dimensional matrix are more important because they are more similar to the situation in vivo and have the potential application of inducing cell migration in the tissue regeneration process. However, the ‘top-down’ and the ‘bottom-up’ technologies are usually applied to manufacturing gradients on planar substrates, but are not suitable or at least need a major modification in a three-dimensional matrix owing to their relative complicate structure. Up to now, only a few technologies have been successfully applied in a three-dimensional matrix including porous scaffolds and hydrogels.

Several techniques have been reported for fabricating physical gradients within scaffolds. Especially, gradients in pore size or porosity are widely studied to mimic the graded tissue morphologies present in vivo [106–108]. For example, Tampieri et al. [29] prepared porosity-gradient hydroxyapatite scaffolds by a multiple and differentiated impregnation procedure. Roy et al. [106] and Woodfield et al. [107] used a three-dimensional printing technology to create polymer scaffolds with porosity gradient and pore size gradient, respectively. Oh et al. [108] developed a centrifugation method to fabricate a poly(ɛ-caprolactone) (PCL) scaffold with gradually increasing pore size and porosity along a cylindrical axis. A centrifugal force was applied to the cylindrical mould containing the fibril-like PCL, followed by fibril bonding with heat treatment. Additionally, gradients with changing microstructure can be fabricated through a temperature gradient technology [109]. The heat-induced phase separation of blends of poly(d,l-lactide) and PCL is modulated by a temperature gradient [110]. This method has also been extended to synthesizing polyurethane copolymers with different block compositions, resulting in diverse microphase separation and a gradient of microstructure [111].

So far, most three-dimensional chemical gradients have been created in hydrogels owing to their similarity to the solutions. DeLong et al. [112] prepared hydrogels with a bFGF gradient by diffusing two types of hydrogel precursor solutions (with/without bFGF) in a gradient maker. Briefly, the poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-conjugated bFGF solution persistently flows into a container having the PEG solution without the bFGF. The two solutions are mixed together and finally pumped into a mould where they are exposed to light to stabilize the concentration gradient. This method can be used to generate various gradients of proteins, peptides and growth factors [8,113]. Microfluidic and diffusion technologies can also be applied to fabricate gradient hydrogels [10,114,115]. Irradiation of photolabile hydrogel matrices with a focused light generates a spatial biomolecule-modified channel with a decreased peptide density towards the bottom. These isolated cell-adhesion regions have proved to be effective in eliciting oriented axonal growth in hydrogels [116]. The compliance gradient is generated by spatially controlling the degree of cross-linking or polymerization. Wong et al. [117] prepared a modulus gradient in polyacrylamide hydrogels by applying a photo mask with a greyscale gradient during photopolymerization.

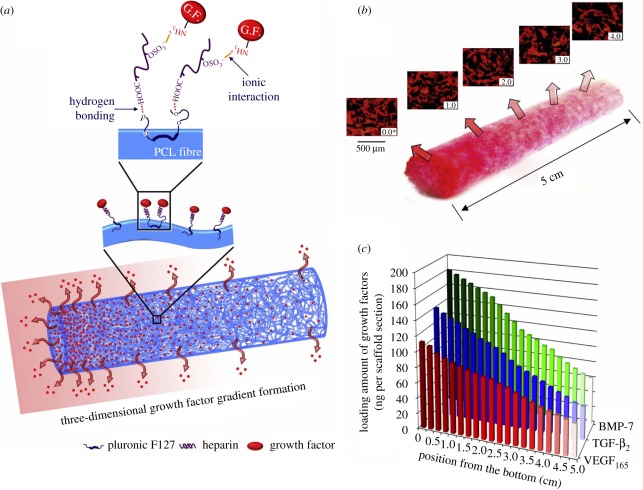

In contrast to hydrogels, preparation of gradients in three-dimensional scaffolds is more difficult and mainly limited to the diffusion method. Vepari and Kaplan put a droplet of 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC)-activated horseradish peroxidase (HRP) solution underneath silk fibrin scaffolds. Along with the HRP solution diffusion upward to the top, an HRP concentration gradient is covalently immobilized within the three-dimensional scaffolds. This diffusion method offers a good control over the gradient slope by changing reaction time and can be extended to couple a variety of proteins on several types of materials [118]. Oh et al. [119] prepared PCL/Pluronic F127 cylindrical scaffolds with a gradually increased growth factor concentration by centrifugation of the fibril-like PCL and subsequent fibril surface immobilization of growth factors (figure 4). The cylindrical scaffolds exhibit gradually increasing surface areas along the longitudinal direction. The growth factors, e.g. bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7), transforming growth factor-β2 (TGF-β2) and VEGF165, are immobilized onto the fibril surfaces via heparin binding to obtain a concentration gradient of the growth factors from top to bottom. The released amount of the growth factor (VEGF165) from the cylindrical scaffolds gradually decreases along the longitudinal direction in a sustained manner for up to 35 days, which can allow for a minutely controlled spatial distribution of growth factors in a three-dimensional environment. Barry et al. [120] used plasma polymer deposition to fabricate a functional scaffold containing a gradient. A thicker layer of the polymer is deposited on the scaffold periphery than in the scaffold centre, leading to more even distribution of cells in the scaffolds.

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic of the successive binding of heparin and the growth factor onto the fibril surface of the PCL/F127 cylindrical scaffold and the formation of a three-dimensional growth factor gradient on the scaffold. (b) Gross appearance and fluorescence microscopy images showing the rhodamine-labelled VEGF165 gradient along the longitudinal direction of the PCL/F127 cylindrical scaffold. The VEGF165 immobilized on the cylindrical scaffold is expressed as a red colour. (c) Loading amount of growth factors (BMP-7, TGF-β2 and VEGF165) immobilized onto the PCL/F127/heparin scaffold sections. The scaffolds show the gradually decreasing concentration of growth factors along the longitudinal direction from the bottom position to the top position (growth factor concentration gradient scaffolds) [119].

4. Influences of gradient biomaterials on cell migration and tissue regeneration

Although many investigations are carried out to correlate cell responses such as adhesion, proliferation, differentiation and migration [121–123] to the physical and chemical cues of the substrate materials, only very limited studies have been carried out to elucidate cell migration patterns on gradient materials. According to the gradients introduced above, generally two categories of gradients can be generated: (i) physical gradients with gradually changing properties such as modulus and topography, and (ii) chemical gradients with spatially changing compositions such as the density and species of functional molecules.

4.1. Physical gradients

Matrix stiffness has a large influence on cell adhesion and mobility. Zaari et al. [102] found that cells which attach to a rigid substrate exhibit a better defined cytoskeleton and filament structure. Pelham & Wang [124] confirmed that cells exhibit higher lamellipodia activity and motility on a soft surface owing to the destabilized adhesion. Thus, a stiffness gradient is expected to guide cell migration as confirmed by Wong et al. and Liang et al. [117,125]. Vascular smooth muscle cells are found to undergo direct migration on a radial gradient-compliant substrate from soft to stiff regions, leading to accumulation of cells in the stiff regions after 24 h (figure 5). The mechanism of cell response to such a physical gradient was studied [126,127]. FAK is involved in mechanical stimulation. For an equal amount of energy, the counterforce provided by the soft substrate is smaller compared with the rigid one because of a longer displacement in the z-direction and higher energy consumption. The stronger feedback makes cells adhere more firmly and spread better on the tough region. Thus, cells migrate directionally through detecting the imbalance in forces from the front to the back [128].

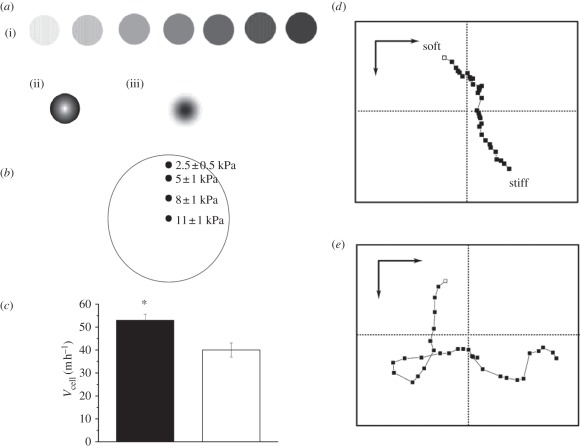

Figure 5.

(a) Mask patterns used to control the intensity of UV light during photopolymerization of acrylamide. Patterns are printed on transparencies using a standard laser printer. (i) Greyscale intensity is shown to vary from 10 to 70%, in increments of 10%. (ii) A radial gradient pattern is used to generate substrata with a gradient in mechanical compliance. The centre of the circle is clear, gradually darkening in increasing greys to black on the outside. (iii) An inverse radial gradient pattern where the centre of the circle is dark, gradually decreasing to clear on the outside. (b) Young's modulus values for a radial-gradient gel using the microindentation method. (c) Cell speed on the polyacrylamide gel polymerized under a 30% grey filter (filled bar) and the polyacrylamide gel polymerized under no filter (open bar). The asterisk indicates that these two datasets are significantly different (p < 0.005). (d) Cell path on a radial-gradient gel. Cells start in the soft region of the gel and translocate towards the stiff region of the gel. (e) Cell path on a uniform-compliance gel polymerized under a 30% grey filter. The arrow length designates 50 mm. Open squares indicate the starting position of the cell [117].

Topography, the configuration of a surface, can largely affect cell migration behaviours. Kim et al. [129] created a model substrate of anisotropic micro- and nanotopographic pattern arrays with a variable local density using UV-assisted capillary force lithography. Fibroblasts adhering on the denser pattern areas align and elongate more strongly along the direction of ridges, while those on the sparser areas exhibit a biphasic dependence of the migration speed on the pattern density. In addition, cells respond to local variations in topography by altering morphology and migration along the direction of grooves biased by the direction of pattern orientation (short term) and pattern density (long term), owing to the distinct types of cytoskeleton reorganization. Mak et al. [130] created a device with gradually narrowing microchannels to test the decision-making processes of cancer cells when they encounter tight spaces in the physiological environment during metastasis within a matrix and during intravasation and extravasation through a vascular wall. The highly metastatic breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) show a more invasive and permeative nature since 87 per cent of the cells migrate into the spatially confining region. By contrast, most of the non-metastatic breast epithelial cells (MCF-10A) (75%) are repolarized (turn around).

4.2. Chemical gradients

Since the cell migration in vivo is widely acknowledged owing to the gradients of ECM proteins, growth factors and other signalling molecules, many chemical gradients are created and used to study their influences on cell migration behaviours in vitro. Synthetic polymer gradients are constructed by alteration of polarity, hydrophilicity, surface energy, charge and even biocompatibility on different positions. Although these gradients can largely regulate cell adhesion, elongation and proliferation, they are generally not efficient enough to guide directional migration of cells.

The gradients of biological molecules have a larger influence on cell migration, depending on both the absolute concentration and the slope of the concentration gradient. Therefore, the source concentration, concentration range and gradient slope should be taken into consideration during the design of the chemical gradients for in vitro cell-based experiments [131]. As there are two chemical gradients in vivo, i.e. one bound to the ECM and the other is soluble, the gradient materials are also divided into two categories: gradients of molecules bound to the substrates and gradients of diffusible factors.

4.2.1. Immobilized gradients

This kind of gradient can be further divided into two subcategories: ECM proteins (including related peptides) and cell growth factors. The ECM proteins consist of several species of proteins including collagen, Fn and laminin. Collagen is a main protein in the ECM that can prominently improve cell adhesion and spreading. Fn and laminin mediate the communication and movement of cells. They have some structure domains that can combine with the receptors on the cell membrane. For example, human Fn contains a peptide sequence of RGD, which can combine with the α5/α8/αδ/αδb integrin subfamily (such as α5β1, α8β1, αδβ1, αδβ3, αδβ5, αδβ6, αδβ8 and αδbβ3) [132]. The collagen is responsible for the interaction with the integrin receptor of α2β1 on cells [133]. The specific interaction between integrin and receptors of fibronectin and laminin transfers the external stimuli into cells. Rajagopalan et al. [134] studied the effect of Fn and RGD on spreading and motility of fibroblasts. Although the migration speed is similar, cells on an Fn-modified surface have a higher traction force that is directly related to the size of focal adhesion, indicating that Fn has a higher affinity towards fibroblasts. Thus, gradients of the ECM protein are supposed to carry the increasing strength of stimuli, making the cells polarize unidirectionally and leading to directional migration. This hypothesis has been demonstrated by several groups. Smith et al. [135] generated Fn concentration gradients on a gold surface and studied the movement of bovine aortic endothelial cells. The cell migration speed increases along with the Fn gradient. The same group also reported that human microvascular endothelial cells migrate faster on the Fn gradient with a larger slope in the range of 0.34–1.23 ng Fn mm–3. The frequency of discrete cellular motion in the gradient direction also increases with the gradient slope [48]. Gunawan et al. created linear, immobilized gradients of laminin by the microfluidic method and studied their influence on cell migration. Rat IEC-6 intestinal crypt-like cells migrate up the gradients regardless of the steepness of the gradients. At the same local laminin concentration, the migration rate is also independent of the gradient steepness. However, cell directedness decreases significantly at a high laminin density [12]. Cai et al. prepared a collagen gradient on the PLLA surface. Endothelial cells cultured on the gradient areas with low and moderate collagen surface densities display a strong motility tendency in parallel to the gradient. However, the endothelial cells cultured on the gradient area with a high collagen density show a reverse response to the collagen gradient, suggesting that cell motility is regulated by the collagen gradient in a surface-density-dependent manner [136].

Usually, a peptide with a functional amino acid sequence of specific proteins can be used as an alternative in gradient preparation because of its high stability and low molecular weight. Adams et al. [137] placed chick embryo dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) in the middle of a grid pattern containing gradients of the Isoleucine-Lysine-Valine-Alanine-Valine peptide, the functional sequence in laminin. DRG growth cones follow a peptide path to the perpendicularly oriented gradients, and most of the growth cones can turn and climb up the gradients. DeLong et al. [8] cultured human dermal fibroblasts on hydrogels with surface gradients of the RGD peptide. The cells align with the gradients and tend to migrate up the gradients. Guarnieri et al. also demonstrated that mouse fibroblasts tend to migrate in the direction of a RGD gradient on hydrogel surfaces. The cell migration speed is higher than that on hydrogels with a uniform distribution of RGD, and increases along with the RGD gradient steepness [138]. Hirschfeld-Warneken et al. [47] found that cells elongate themselves along the gradient on a substrate with a larger ligand distance (figure 6). Theoretical calculation based on a one-dimensional continuum viscoelastic model is used to predict the migration speed of a single cell in response to a linear ligand density gradient across a solid substrate as a function of gradient slopes. The model predicts biphasic dependence between migration speed and gradient slope with a maximum speed at an intermediate gradient slope, above which the cell speed decreases with increasing slope [139].

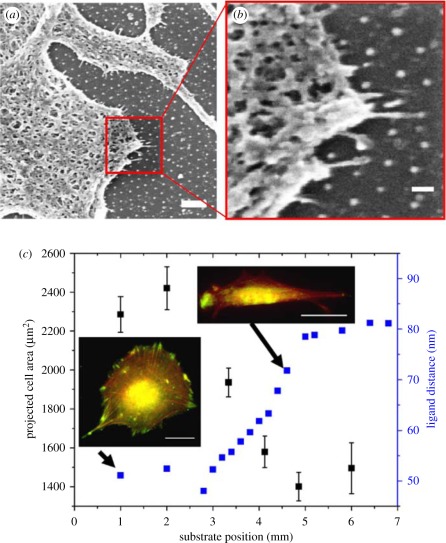

Figure 6.

(a,b) Mc3t3 osteoblasts in contact with a biofunctionalized 80 nm pattern and exhibiting cell protrusions sensing the pattern. Scale bars, (a) 20 μm and (b) 200 nm. (c) Projected cell area (±s.e.m.) as a function of substrate position. Insets: Mc3t3 osteoblasts after 23 h adherence on a homogeneously nanopatterned area with 50 nm c(-RGDfK-) patch spacing (left) and along the spacing gradient (right), respectively. Cells are immunostained for vinculin (green), and actin is visualized using TRITC (6-tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate)-phalloidin (red). Scale bars, 20 mm [47].

Besides ECM proteins and related peptides, different kinds of growth factors are immobilized in a gradient form to investigate their effect on cell migration too. DeLong et al. [112] synthesized hydrogels with bFGF gradients and observed that aortic smooth muscle cells align in the direction of the gradients and migrate towards the increasing bFGF concentration. Liu et al. [140] found that the directional migration of endothelial cells is largely promoted by a gradient of VEGF, and furthermore, increased another twofold on the combinational gradients of VEGF and Fn (figure 7). Stefonek-Puccinelli and Masters found that keratinocytes exhibit almost 10-fold directional migration at an optimal concentration at an EGF gradient compared with that on an EGF-free surface. Immobilization of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) gradients also accelerates and directs keratinocyte migration. However, no difference in migration is found when EGF and IGF-1 gradients are combined [141].

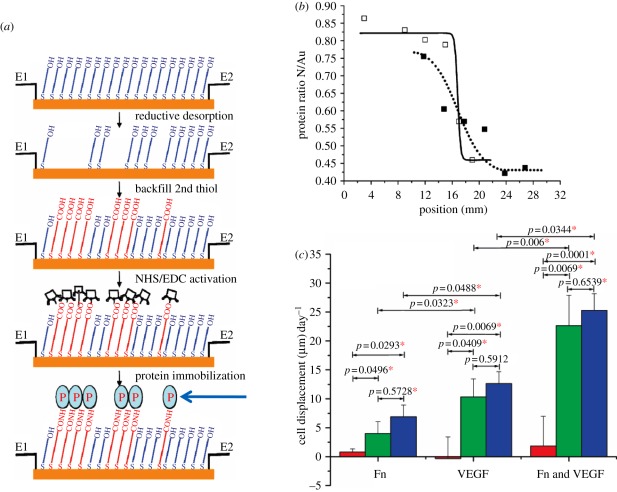

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic of the process to produce a surface density gradient of a protein using an electrochemical approach. (b) Integrated area of the carbonyl band at 1735 cm–1 measured from FTIR as a function of position for two C15COOH/C11OH gradients after EDC/N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) activation. (c) Bovine aortic endothelial cell displacements along gradients towards higher protein surface densities after 24 h cell culture. Data shown are for uniform (red bar), steep or sharp gradient (green bar), and smooth gradient (blue bar) surfaces of Fn, VEGF or both. Asterisks denote significant difference between two compared results (p < 0.05) [140].

4.2.2. Soluble-factor gradients

Besides the immobilized chemical gradients, the soluble-factor gradients that can mimic a natural three-dimensional environment are also widely used to guide cell migration. For example, Frevert et al. developed a gradient of interleukin-8 by a microvalve-actuated chemotaxis device. Single neutrophils can be tracked preferably to migrate to the higher concentration of interleukin-8 at a local concentration of up to 200 ng ml–1, whereas chemokinesis plays a more dominant role in neutrophil migration at higher local interleukin-8 concentrations [142]. Besides, bFGF, stromal cell-derived factor, EGF, VEGF and IGF are usually used as chemotactic agents [112,143–145]. Wang et al. found that metastatic breast cancer cells can migrate towards a higher EGF concentration with a nonlinear polynomial profile [146]. However, there are some factors that can inhibit cell mobility, such as TGF-β1 [147] and angiotensin 1 [148].

4.3. Combinational gradients

Study of cell motility on a combined gradient will provide insight into the complex physiological environment that guides and directs cell migration. Hale et al. designed a polyacrylamide hydrogel with a 100 μm interfacial region. The chemical and mechanical properties gradually vary in opposite directions: one side of the interface is stiff with a low collagen (type I) concentration, and the other side is compliant with a high collagen concentration. The Balb/c 3T3 fibroblasts either migrate preferentially towards the high-collagen-compliant side of the interfacial gradient region, or remain on the high-collagen region, suggesting a more dominant role for chemical gradient in directing fibroblast movement [149].

4.4. Cell migration in a three-dimensional matrix and possible application in tissue regeneration

The cell migration behaviours as a function of gradients in three-dimensional scaffolds and hydrogels have also been demonstrated. Dodla and Bellamkonda cast DRGs in agarose gels and prepared laminin gradients by photochemistry after diffusion. The presence of laminin gradients in the hydrogels significantly enhances the rate of neurite extension [150]. Moore et al. [151] used a gradient maker to cast poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA) gels containing gradients of NGF and neurotrophin-3 that are immobilized during photocrosslinking of the pHEMA. DRG cells seeded atop the gels penetrate into the gels during culture. The cells extend neurites up the gradients only when the gradients of both factors are present, suggesting a synergistic effect. Musoke-Zawedde and Shoichet [152] used UV laser micropatterning to fabricate RGD peptide gradients in hyaluronan gels, which can guide neurite outgrowth from primary neural cells.

Tampieri et al. [29] implanted ceramic scaffolds containing a gradient in porosity into rabbit femur defects. New bone formation is enhanced in the higher porosity regions of the scaffolds. Roy et al. [106] implanted polymer–ceramic composite scaffolds containing a porosity gradient in rabbit calvarial defects. More new bone is formed in the high-porosity zones than in the low-porosity zones. Hofmann et al. [153] demonstrated that silk scaffolds with pore size gradients would induce the formation of a tissue with a graded morphology. Oh et al. tested the cell/tissue responses to a scaffold with a pore size/porosity gradient in vitro and in vivo. Chondrocytes and osteoblasts contribute to the major components of a tissue in a large pore/high porosity part, while the fibroblast number is higher in a smaller pore size/lower porosity part of the scaffolds in vitro. Bone formation after implantation into rabbit calvarial defects is highest in mid-range pore size/porosity scaffolds [108]. By modulating the standard electrospinning process, Sundararaghavan and Burdick [154] prepared the gradients of increasing modulus and RGD ligand density across the thickness of a fibrous hyaluronic acid scaffold. The chick aortic arch explants have significantly greater cell infiltration into the scaffold along with the increase in RGD density gradient compared with the scaffold with a uniform RGD distribution. Lühmann et al. [39] studied cell alignment on two-dimensional or within three-dimensional gradients of the matrix-bound 6th Ig-like domain of cell adhesion molecule L1 (TG-L1Ig6). Both gradients have a greater promotion for cell guidance (figure 8).

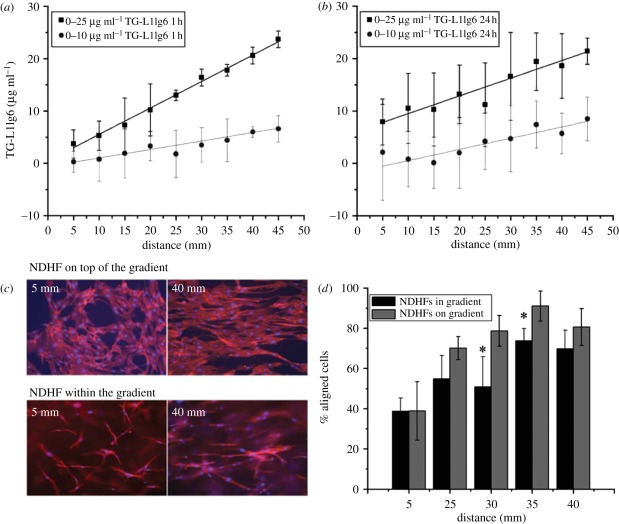

Figure 8.

(a,b) Gradient steepness and stability of TG-L1Ig6-Alexa-488 in three-dimensional fibrin matrices. The gradient matrices with steepness of 0–10 mg and 0–25 mg ml–1 TG-L1Ig6-Alexa-488 incorporated into 2 mg ml–1 fibrin-based matrices are analysed (a) 1 and (b) 24 h after polymerization. (c) Normal dermal human fibroblasts (NDHF) adhered on the top and within three-dimensional fibrin matrices containing a gradient of 0–10 mg ml–1 TG-L1Ig6. (d) The fibroblasts align with the direction of the gradient (increase between 5 and 40 mm from the beginning of the 0–10 mg ml–1 gradient of TG-L1Ig6 [39].

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

Varieties of top-down and bottom-up technologies have been developed to produce two-dimensional and three-dimensional gradient materials with gradually changing physical properties, immobilized molecules and soluble factors, mimicking the microenvironment in vivo and proving the possibility of guiding cell directional migration in vitro. Complex shapes or multiple factor gradients, including combined chemical and physical gradients, have also been created to better mimic the complicated environment in vivo. Most of the current works on cell migration on gradient materials pertain to planar surfaces. Studies are beginning to appear on the migration behaviours of cells encapsulated in three-dimensional matrices, more closely mimicking the situation in vivo. The gradients in three-dimensional scaffolds are somewhat more complex to fabricate and characterize [155]. More importantly, measuring the response of cells encapsulated in three-dimensional matrices is also more challenging.

Ongoing and future research is tasked with improving gradient generation methods and integrating them to cell migration behaviours in vitro and in vivo, shedding light on the regeneration of tissues and organs with complex structures and functions. Advanced methods should be developed to prepare gradients with controlled shape and stability as well as multiple functions. Improved and standardized methods are also required to properly correlate cell response to the applied gradients and biological cues. Moreover, material synthesis techniques should be sufficiently advanced to create physiologically relevant gradient materials to study complex spatio-temporal phenomena such as tissue morphogenesis. Smart biomaterials incorporated with multiple gradient cues inside scaffolds, which mimic the cellular and structural characteristics of native tissues, could then be created for the regeneration of tissues having complex and multiple types of cells [156].

Acknowledgements

This study is financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (20934003), and the Major State Basic Research Programme of China (2011CB606203). Z.W.M. thanks the Zijing project of Zhejiang University.

References

- 1.Godwin J. W., Brockes J. P. 2006. Regeneration, tissue injury and the immune response. J. Anat. 209, 423–432 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00626.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00626.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagur-Grodzinski J. 2006. Polymers for tissue engineering, medical devices, and regenerative medicine. Concise general review of recent studies. Polym. Adv. Technol. 17, 395–418 10.1002/pat.729 (doi:10.1002/pat.729) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redd M. J., Kelly G., Dunn G., Way M., Martin P. 2006. Imaging macrophage chemotaxis in vivo: studies of microtubule function in zebrafish wound inflammation. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 63, 415–422 10.1002/cm.20133 (doi:10.1002/cm.20133) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cara D. C., Kaur J., Forster M., McCafferty D. M., Kubes P. 2001. Role of P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in chemokine-induced emigration and chemotaxis in vivo. J. Immunol. 167, 6552–6558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramón Y., Cajal S. 1892. La retine de vertebres. La Cellule 9, 119–258 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keenan T. M., Folch A. 2008. Biomolecular gradients in cell culture systems. Lab. Chip 8, 34–57 10.1039/b711887b (doi:10.1039/b711887b) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genzer J., Bhat R. R. 2008. Surface-bound soft matter gradients. Langmuir 24, 2294–2317 10.1021/la7033164 (doi:10.1021/la7033164) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLong S. A., Gobin A. S., West J. L. 2005. Covalent immobilization of RGDs on hydrogel surfaces to direct cell alignment and migration. J. Cont. Release 109, 139–148 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.020 (doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung S., Sudo R., Vickerman V., Zervantonakis I. K., Kamm R. D. 2010. Microfluidic platforms for studies of angiogenesis, cell migration, and cell–cell interactions. Sixth International Bio-Fluid Mechanics Symposium and Workshop, March 28–30, 2008, Pasadena, California. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 1164–1177 10.1007/s10439-010-9899-3 (doi:10.1007/s10439-010-9899-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mimura T., Imai S., Kubo M., Isoya E., Ando K., Okumura N., Matsusue Y. 2008. A novel exogenous concentration-gradient collagen scaffold augments full-thickness articular cartilage repair. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 16, 1083–1091 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.003 (doi:10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh M., Berkland C., Detamore M. S. 2008. Strategies and applications for incorporating physical and chemical signal gradients in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. B Rev. 14, 341–366 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0304 (doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0304) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunawan R. C., Silvestre J., Gaskins H. R., Kenis P. J., Leckband D. E. 2006. Cell migration and polarity on microfabricated gradients of extracellular matrix proteins. Langmuir 22, 4250–4258 10.1021/la0531493 (doi:10.1021/la0531493) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin P. 1997. Wound healing-aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 276, 75–81 10.1126/science.276.5309.75 (doi:10.1126/science.276.5309.75) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein L. R., Liotta L. A. 1994. Molecular mediators of interactions with extracellular matrix components in metastasis and angiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 6, 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed F., et al. 2002. GFP expression in the mammary gland for imaging of mammary tumor cells in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 62, 7166–7169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raftopoulou M., Hall A. 2004. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev. Biol. 265, 23–32 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003 (doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchison T. J., Cramer L. P. 1996. Actin-based cell motility and cell locomotion. Cell 84, 371–379 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81281-7 (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81281-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J., Mao Z., Gao C. 2012. Controlling the migration behaviors of vascular smooth muscle cells by methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) brushes of different molecular weight and density. Biomaterials 33, 810–820 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.022 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridley A. J., Schwartz M. A., Burridge K., Firtel R. A., Ginsberg M. H., Borisy G., Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. R. 2003. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704–1709 10.1126/science.1092053 (doi:10.1126/science.1092053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wehrle-Haller B., Imhof B. A. 2003. Actin, microtubules and focal adhesion dynamics during cell migration. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 35, 39–50 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00071-7 (doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00071-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall A. 2005. Rho GTPases and the control of cell behaviour. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 891–895 10.1042/BST20050891 (doi:10.1042/BST20050891) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong K., et al. 2001. Signal transduction in neuronal migration: roles of GTPase activating proteins and the small GTPase Cdc42 in the Slit-Robo pathway. Cell 107, 209–221 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00530-X (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00530-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manabe R., Kovalenko M., Webb D. J., Horwitz A. R. 2002. GIT1 functions in a motile, multi-molecular signaling complex that regulates protrusive activity and cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 115, 1497–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klemke R. L., Cai S., Giannini A. L., Gallagher P. J., de Lanerolle P., Cheresh D. A. 1997. Regulation of cell motility by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Cell Biol. 137, 481–492 10.1083/jcb.137.2.481 (doi:10.1083/jcb.137.2.481) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheresh D. A., Leng J., Klemke R. L. 1999. Regulation of cell contraction and membrane ruffling by distinct signals in migratory cells. J. Cell Biol. 146, 1107–1116 10.1083/jcb.146.5.1107 (doi:10.1083/jcb.146.5.1107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen D. H., Catling A. D., Webb D. J., Sankovic M., Walker L. A., Somlyo A. V., Weber M. J., Gonias S. L. 1999. Myosin light chain kinase functions downstream of Ras/ERK to promote migration of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-stimulated cells in an integrin-selective manner. J. Cell Biol. 146, 149–164 10.1083/jcb.146.1.149 (doi:10.1083/jcb.146.1.149) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obermeier A., Ahmed S., Manser E., Yen S. C., Hall C., Lim L. 1998. PAK promotes morphological changes by acting upstream of Rac. EMBO J. 17, 4328–4339 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4328 (doi:10.1093/emboj/17.15.4328) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin S., Sangaj N., Razafiarison T., Zhang C., Varghese S. 2011. Influence of physical properties of biomaterials on cellular behavior. Pharm. Res. 28, 1422–1430 10.1007/s11095-011-0378-9 (doi:10.1007/s11095-011-0378-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tampieri A., Celotti G., Sprio S., Delcogliano A., Franzese S. 2001. Porosity-graded hydroxyapatite ceramics to replace natural bone. Biomaterials 22, 1365–1370 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00290-8 (doi:10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00290-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karageorgiou V., Kaplan D. 2005. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 26, 5474–5491 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cullinane D. M., Einhorn T. A. 2002. Biomechanics of bone. In Principles of bone biology (eds Bilezikian J., Raisz L. G., Rodan G. A.), pp. 17–32 San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho S. P., Marshall S. J., Ryder M. I., Marshall G. W. 2007. The tooth attachment mechanism defined by structure, chemical composition and mechanical properties of collagen fibers in the periodontium. Biomaterials 28, 5238–5245 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.031 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.031) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones C. M., Smith J. C. 1998. Establishment of a BMP-4 morphogen gradient by long-range inhibition. Dev. Biol. 194, 12–17 10.1006/dbio.1997.8752 (doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8752) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piccolo S., Agius E., Leyns L., Bhattacharyya S., Grunz H., Bouwmeester T., De Robertis E. M. 1999. The head inducer cerberus is a multifunctional antagonist of nodal, BMP and Wnt signals. Nature 397, 707–710 10.1038/17820 (doi:10.1038/17820) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers D. C., Sepich D. S., Solnica-Krezel L. 2002. BMP activity gradient regulates convergent extension during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev. Biol. 243, 81–98 10.1006/dbio.2001.0523 (doi:10.1006/dbio.2001.0523) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isbister C. M., Mackenzie P. J., To K. C., O'Connor T. P. 2003. Gradient steepness influences the pathfinding decisions of neuronal growth cones in vivo. J. Neurosci. 23, 193–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou S., Cui Z., Urban J. P. 2008. Nutrient gradients in engineered cartilage: metabolic kinetics measurement and mass transfer modeling. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 101, 408–421 10.1002/bit.21887 (doi:10.1002/bit.21887) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swartz M. A., Fleury M. E. 2007. Interstitial flow and its effects in soft tissues. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 9, 229–256 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151850 (doi:10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151850) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lühmann T., Hall H. 2009. Cell guidance by 3D-gradients in hydrogel matrices: importance for biomedical applications. Materials 1058–1083 10.3390/ma2031058 (doi:10.3390/ma2031058) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruhrberg C., Gerhardt H., Golding M., Watson R., Ioannidou S., Fujisawa H., Betsholtz C., Shima D. T. 2002. Spatially restricted patterning cues provided by heparin-binding VEGF: a control blood vessel branching morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 16, 2684–2698 10.1101/gad.242002 (doi:10.1101/gad.242002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito Y., Heydari M., Hashimoto A., Konno T., Hirasawa A., Hori S., Kurita K., Nakajima A. 2007. The movement of a water droplet on a gradient surface prepared by photodegradation. Langmuir 23, 1845–1850 10.1021/la0624992 (doi:10.1021/la0624992) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singer S. J., Kupfer A. 1986. The directed migration of eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 2, 337–365 10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.002005 (doi:10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.002005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lauffenburger D. A., Horwitz A. F. 1996. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell 84, 359–369 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81280-5 (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81280-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan S. J., Daukas G., Zigmond S. H. 1984. Asymmetric distribution of the chemotactic peptide receptor on polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Cell Biol. 99, 1461–1467 10.1083/jcb.99.4.1461 (doi:10.1083/jcb.99.4.1461) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan E. W., Yousaf M. N. 2008. A photo-electroactive surface strategy for immobilizing ligands in patterns and gradients for studies of cell polarization. Mol. Biosyst. 4, 746–753 10.1039/b801394b (doi:10.1039/b801394b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnold M., et al. 2008. Induction of cell polarization and migration by a gradient of nanoscale variations in adhesive ligand spacing. Nano Lett. 8, 2063–2069 10.1021/nl801483w (doi:10.1021/nl801483w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirschfeld-Warneken V. C., Arnold M., Cavalcanti-Adam A., Lopez-Garcia M., Kessler H., Spatz J. P. 2008. Cell adhesion and polarisation on molecularly defined spacing gradient surfaces of cyclic RGDfk peptide patches. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 87, 743–750 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.03.011 (doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.03.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith J. T., Elkin J. T., Reichert W. M. 2006. Directed cell migration on fibronectin gradients: effect of gradient slope. Exp. Cell Res. 312, 2424–2432 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.04.005 (doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.04.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgenthaler S., Zink C., Spencer N. D. 2008. Surface chemical and morphological gradients. Soft Matter 4, 419–434 10.1039/b715466f (doi:10.1039/b715466f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tu R. S., Tirrell M. 2004. Bottom-up design of biomimetic assemblies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 56, 1537–1563 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.047 (doi:10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.047) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spijker H. T., Bos R., Busscher H. J., van Oeveren W., de Vries J., Busscher H. J. 1999. Protein adsorption on gradient surfaces on polyethylene prepared in a shielded gas plasma. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 15, 89–97 10.1016/S0927-7765(99)00056-9 (doi:10.1016/S0927-7765(99)00056-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shin Y. N., Kim B. S., Ahn H. H., Lee J. H., Kim K. S., Lee J. Y., Kim M. S., Khang G., Lee H. B. 2008. Adhesion comparison of human bone marrow stem cells on a gradient wettable surface prepared by corona treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 255, 293–296 10.1016/j.apsusc.2008.06.173 (doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2008.06.173) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blondiaux N., Zurcher S., Liley M., Spencer N. D. 2007. Fabrication of multiscale surface-chemical gradients by means of photocatalytic lithography. Langmuir 23, 3489–3494 10.1021/la063186+ (doi:10.1021/la063186+) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mangindaan D., Kuo W., Wang Y., Wang M. 2010. Experimental and numerical modeling of the controllable wettability gradient on poly(propylene) created by SF(6) plasma. Plasma Process Polym. 7, 754–765 10.1002/ppap.201000021 (doi:10.1002/ppap.201000021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pitt W. G. 1989. Fabrication of a continuous wettability gradient by radio frequency plasma discharge. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 133, 223–227 10.1016/0021-9797(89)90295-6 (doi:10.1016/0021-9797(89)90295-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golander C. G., Pitt W. G. 1990. Characterization of hydrophobicity gradients prepared by means of radio frequency plasma discharge. Biomaterials 11, 32–35 10.1016/0142-9612(90)90048-U (doi:10.1016/0142-9612(90)90048-U) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whittle J. D., Bartonab D., Alexanderc M. R., Short R. D. 2003. A method for the deposition of controllable chemical gradients. Chem. Commun. 1766–1767 10.1039/B305445B (doi:10.1039/B305445B) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee J. H., Khang G., Lee J. W., Lee H. B. 1998. Interaction of different types of cells on polymer surfaces with wettability gradient. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 205, 323–330 10.1006/jcis.1998.5688 (doi:10.1006/jcis.1998.5688) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee J. H., Khang G., Lee J. W., Lee H. B. 1998. Platelet adhesion onto chargeable functional group gradient surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 40, 180–186 (doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199805)40:2<180::AID-JBM2>3.0.CO;2-H) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee J. H., Lee S. J., Khang G., Lee H. B. 2000. The effect of fluid shear stress on endothelial cell adhesiveness to polymer surfaces with wettability gradient. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 230, 84–90 10.1006/jcis.2000.7080 (doi:10.1006/jcis.2000.7080) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim M. S. K., Khangb G., Lee H. B. 2008. Gradient polymer surfaces for biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 33, 138–164 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.06.001 (doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.06.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee J. H., Lee H. B. 1993. A wettability gradient as a tool to study protein adsorption and cell adhesion on polymer surfaces. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 4, 467–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim M. S., Seo K. S., Khang G., Lee H. B. 2005. First preparation of biotinylated gradient polyethylene surface to bind photoactive caged streptavidin. Langmuir 21, 4066–4070 10.1021/la046868a (doi:10.1021/la046868a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee J. H., Kim H. W., Pak P. K., Lee H. B. 2003. Preparation and characterization of functional group gradient surfaces. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Chem. 32, 1569–1579 10.1002/pola.1994.080320818 (doi:10.1002/pola.1994.080320818) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gijsman P., Meijers G., Vitarelli G. 1999. Comparison of the UV-degradation chemistry of polypropylene, polyethylene, polyamide 6 and polybutylene terephthalate. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 65, 433–441 10.1016/S0141-3910(99)00033-6 (doi:10.1016/S0141-3910(99)00033-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li B., Ma Y., Wang S., Moran P. M. 2005. A technique for preparing protein gradients on polymeric surfaces: effects on pc12 pheochromocytoma cells. Biomaterials 26, 1487–1495 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.004 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li B., Ma Y., Wang S., Moran P. M. 2005. Influence of carboxyl group density on neuron cell attachment and differentiation behavior: gradient-guided neurite outgrowth. Biomaterials 26, 4956–4963 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.018 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ding Y. X., Streitmatter S., Wright B. E., Hlady V. 2010. Spatial variation of the charge and sulfur oxidation state in a surface gradient affects plasma protein adsorption. Langmuir 26, 12 140–12 146 10.1021/la101674b (doi:10.1021/la101674b) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu Y., Gao C., Liu X., He T., Shen J. 2004. Immobilization of biomacromolecules onto aminolyzed poly(l-lactic acid) toward acceleration of endothelium regeneration. Tissue Eng. 10, 53–61 10.1089/107632704322791691 (doi:10.1089/107632704322791691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhu Y., Gao C., He T., Shen J. 2004. Endothelium regeneration on luminal surface of polyurethane vascular scaffold modified with diamine and covalently grafted with gelatin. Biomaterials 25, 423–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu Y., Gao C., Liu Y., Shen J. 2004. Endothelial cell functions in vitro cultured on poly(l-lactic acid) membranes modified with different methods. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 69, 436–443 10.1002/jbm.a.30007 (doi:10.1002/jbm.a.30007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li C. Y., Yuan W., Jiang H., Li J. S., Xu F. J., Yang W. T., Ma J. 2011. PCL film surfaces conjugated with p(DMAEMA)/gelatin complexes for improving cell immobilization and gene transfection. Bioconjug. Chem. 22, 1842–1851 10.1021/bc200241m (doi:10.1021/bc200241m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ueda-Yukoshi T., Matsuda T. 1995. Cellular responses on a wettability gradient surface with continuous variations in surface compositions of carbonate and hydroxyl groups. Langmuir 10, 4135–4140 10.1021/la00010a080 (doi:10.1021/la00010a080) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tan H., Wan L., Wu J., Gao C. 2008. Microscale control over collagen gradient on poly(l-lactide) membrane surface for manipulating chondrocyte distribution. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 67, 210–215 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.08.019 (doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.08.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu J., Tan H., Li L., Gao C. 2009. Covalently immobilized gelatin gradients within three-dimensional porous scaffolds. Chinese Sci. Bull. 54, 3174–3180 10.1007/s11434-009-0215-2 (doi:10.1007/s11434-009-0215-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Han L., Mao Z., Wuliyasu H., Wu J., Gong X., Yang Y., Gao C. 2011. Modulating the structure and properties of poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate)/poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) multilayers with concentrated salt solutions. Langmuir 28, 193–199 10.1021/la2040533 (doi:10.1021/la2040533) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kunzler T. P., Drobek T., Schuler M., Spencer N. D. 2007. Systematic study of osteoblast and fibroblast response to roughness by means of surface-morphology gradients. Biomaterials 28, 2175–2182 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.019 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang L., Peng B., Su Z. 2010. Tunable wettability and rewritable wettability gradient from superhydrophilicity to superhydrophobicity. Langmuir 26, 12 203–12 208 10.1021/la101064c (doi:10.1021/la101064c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riepl M., Ostblom M., Lundstrom I., Svensson S. C., Denier V. D. G. A., Schaferling M., Liedberg B. 2005. Molecular gradients: an efficient approach for optimizing the surface properties of biomaterials and biochips. Langmuir 21, 1042–1050 10.1021/la048358m (doi:10.1021/la048358m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kraus T., Stutz R., Balmer T. E., Schmid H., Malaquin L., Spencer N. D., Wolf H. 2005. Printing chemical gradients. Langmuir 21, 7796–7804 10.1021/la0506527 (doi:10.1021/la0506527) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi S., Zhang Newby B. 2003. Micrometer-scaled gradient surfaces generated using contact printing of octadecyltrichlorosilane. Langmuir 19, 7427–7435 10.1021/la035027l (doi:10.1021/la035027l) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dertinger S. K. W., Chiu D. T., Jeon N. L., Whitesides G. M. 2001. Generation of gradients having complex shapes using microfluidic networks. Anal. Chem. 73, 1240–1246 10.1021/ac001132d (doi:10.1021/ac001132d) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Venkateswar R. A., Branch D. W., Wheeler B. C. 2000. An electrophoretic method for microstamping biomolecule gradients. Biomed. Microdevices 2, 255–264 10.1023/A:1009999004367 (doi:10.1023/A:1009999004367) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tomlinson M. R., Genzer J. 2003. Formation of grafted macromolecular assemblies with a gradual variation of molecular weight on solid substrates. Macromolecules 36, 3449–3451 10.1021/ma025937u (doi:10.1021/ma025937u) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matyjaszewski K., et al. 1999. Polymers at interfaces: using atom transfer radical polymerization in the controlled growth of homopolymers and block copolymers from silicon surfaces in the absence of untethered sacrificial initiator. Macromolecules 32, 8716–8724 10.1021/ma991146p (doi:10.1021/ma991146p) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu X., Wang Z., Jiang Y., Zhang X. 2006. Surface gradient material: from superhydrophobicity to superhydrophilicity. Langmuir 22, 4483–4486 10.1021/la053133c (doi:10.1021/la053133c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li L., Zhu Y., Li B., Gao C. 2008. Fabrication of thermoresponsive polymer gradients for study of cell adhesion and detachment. Langmuir 24, 13 632–13 639 10.1021/la802556e (doi:10.1021/la802556e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morgenthaler S., Lee S., Zrcher S., Spencer N. D. 2003. A simple, reproducible approach to the preparation of surface-chemical gradients. Langmuir 19, 10 459–10 462 10.1021/la034707l (doi:10.1021/la034707l) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]