Abstract

Background/Aims

Ischemic colitis (IC) is usually a self-limiting disease. But, it can cause necrosis that requires urgent surgical treatment. We sought to evaluate clinical difference in IC patients between medical and surgical treatment groups, and to identify prognostic factors for adverse outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics in patients with IC treated in Chonnam National University Hospital between May 2001 and April 2010. A total of 81 patients with IC were enrolled. We classified the patients into two groups-a medical treatment group and a surgical treatment group-and evaluated their clinical features, treatment outcomes and mortality.

Results

Absence of hematochezia, vomiting, abdominal tenderness, abdominal rebound tenderness, heart rate over 90 beats/min, systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg, hyponatremia and increased LDH or serum creatinine level were observed more frequently in surgically-treated patients (p<0.05). Most cases in the medically-treated group resolved without complications (98.3%). But, about half of the cases (52.4%) of the surgically-treated group resolved and the mortality rate was 47.6%.

Conclusions

In patients with ischemic colitis, several clinical factors are associated with surgical treatment. Although IC is often selflimited, our data suggests that special attention and aggressive therapy is warranted in treating these patients.

Keywords: Ischemic colitis, Surgery, Clinical factor, Hematochezia, Rebound tenderness

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic colitis (IC) is the most common form of bowel ischemia and occurs with greater frequency in the elderly. There are various clinical symptoms of ischemic colitis and the most common symptoms include abdominal pain, hematochezia and diarrhea.1 IC is occurred with risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart disease, congestive heart disease, hyperlipidemia and vasoactive medicine history, but these are not established yet since risk factors are hard to confirm in most cases.2,3 IC is diagnosed by combining clinical, biochemical, radiological, colonoscopic, and pathologic findings since the symptoms of IC are not specific and there is no specific examination for IC diagnosis.4 Most non-necrotic IC could be improved without special complication by conservative treatment consisting of dehydration correction, drugs that contract mesenteric vessels and extensive antibiotics together with fasting.5 Full-thickness necrotic IC or ischemia of the whole colon, however, often requires surgical treatment in addition to medical treatment. Mortality of such cases is reported between 29% and 75% despite aggressive medical or surgical treatment.6,7 It is very important, therefore, to identify prognostic factors that can predict adverse outcomes and to perform initial screening in patients who are expected to show poor prognosis, before deciding treatment modality. This study performed a comparative analysis between medical treatment and surgical treatment in IC patients to evaluate differences from baseline clinical characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Between May 2001 and April 2010, we performed a retrospective analysis in 81 patients who were diagnosed as IC in Chonnam National University Hospital. Patients with acute presentation of symptoms such as abdominal pain and hematochezia but without history of inflammatory bowel diseases including ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease and medication history such as antibiotics immediately before symptom presentation and negative stool culture result were diagnosed as IC when reasonable by colonoscopy or abdominal computed tomography (CT). Patients were classified into two groups; medical treatment group and surgical treatment group. Medical treatment group was defined as patients who received conservative treatment only, and surgical treatment group as patients who received surgical treatment (n=18) or patients whose family refused scheduled surgery due to underlying disease or old age (n=3).

Methods

In this retrospective analysis, we compared the patients enrolled in medical treatment group and surgical treatment group by their age, gender, underlying medical illness, symptom, physical examination, colonoscopy, treatment and clinical course based on medical records. IC was diagnosed when there is agreement between colonoscopist's description of finding and another gastroenterologists' opinion, and abdominal CT was analyzed based on an experienced radiologist's reading. Colon was categorized and characterized as right colon (proximal portion of the splenic flexure) involvement, left colon (distal portion of the splenic flexure) involvement, or whole colon involvement.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test was performed for between-group analysis. Multiple regression analysis using stepwise variable selection was performed to find clinical factors that influence treatment modality and their influences. A p-value less than 0.05 was determined significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of enrolled patients

Overall 81 patients were diagnosed as IC. Mean age of these patients were 64.09±14.42 years old. Thirty-six (44.4%) were male and 45 (55.6%) were female patients. The most common underlying medical illness were hypertension (n=24, 29.6%) and DM (n=17, 21.0%), followed by coronary artery disease, liver cirrhosis and cerebrovascular disease (n=5, 6.2% each), congestive heart failure (n=2, 2.5%), and end-stage renal disease (ESRD; n=1). The most common symptoms were abdominal pain (n=61, 75.3%) followed by hematochezia (n=43, 53.1%), diarrhea (n=29, 35.8%), and vomiting (n=11, 13.6%). The median time to admission after symptom presentation was 3.53±6.34 days. IC was diagnosed, in addition to clinical symptoms, by barium study, colonoscopy, and abdominal CT in 3 (3.7%), 56 (69.1%), and 56 (69.1%) patients, respectively. Left colon was most commonly involved (41 cases, 50.6%) followed by right colon (32 cases, 39.5%) and whole colon (8 cases, 9.9%). At admission, patients showed abdominal tenderness (n=40, 49.4%) or abdominal rebound tenderness (n=18, 22.2%) at physical examination, and leukocytosis (leukocyte count ≥10,000/L; n=40, 49.4%), serum creatinine elevation (serum Cr >1.2 mg/dL; n=23, 28.4%), or C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation above 1 mg/dL (n=58, 71.6%) were reported at laboratory findings. Seventy patients (86.4%) were recovered after treatment; 11 patients (13.6%) died (Tables 1, 2).

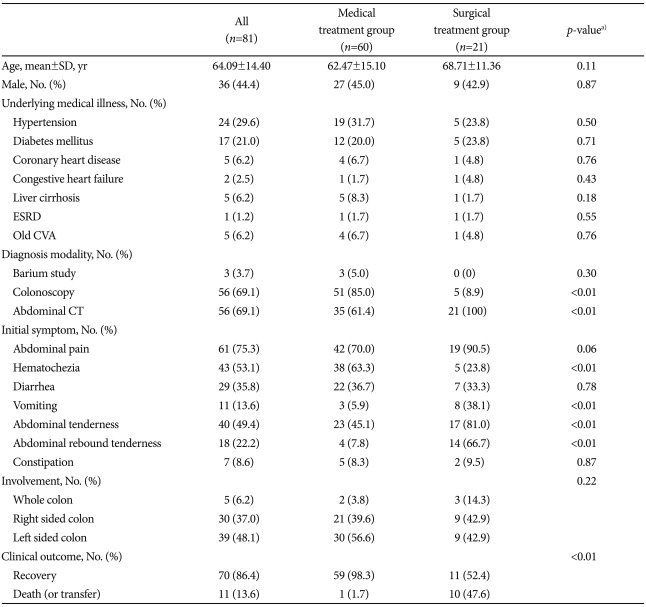

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Patients with Ischemic Colitis

SD, standard deviation; ESRD, end stage renal disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; CT, computed tomography.

a)p-value was calculated by chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test.

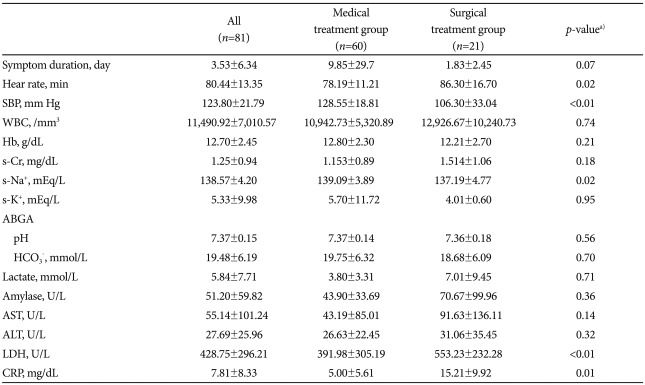

Table 2.

Clinical Presentations at Admission (I)

Values are presented as mean±SD.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; s-Cr, serum creatinine; ABGA, arterial blood gas analysis; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein.

a)p-value was calculated by chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test.

Comparison of clinical characteristics according to treatment

Among 81 patients diagnosed as IC, 60 patients received medical treatment and 21 patients received surgical treatment. The mean age of medical treatment group was 62.47±15.10 years old, 27 (45.0%) were male and 33 (55.0%) were female patients. The mean age of surgical treatment group was 68.71±11.36 years old, 9 (42.9%) were male and 12 (7.1%) were female patients. There was no significant difference in mean age and gender ratio between the groups (Table 1).

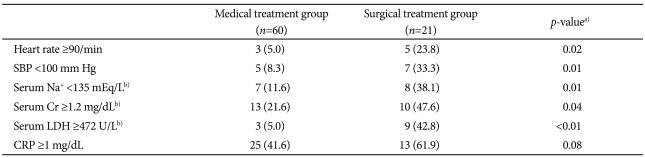

Vomiting (5.9% vs. 38.1%, p<0.01), abdominal tenderness (45.1% vs. 81.0%, p<0.01), and abdominal rebound tenderness (7.8% vs. 66.7%) were more common as initial symptoms in surgical treatment group; hematochezia (53.1% vs. 63.3%, p=0.02) was more common in medical treatment group. With regard to vital signs at admission, significantly more patients at surgical treatment group showed heart rate over 90 beats/min (5.0% vs. 23.8%, p=0.02) or systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg (8.3% vs. 33.3%, p=0.01). With regard to laboratory findings, serum Na+ was significantly higher in medical treatment group (p=0.02), and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and CRP were significantly higher in surgical treatment group (both p<0.01). Significantly more patients in surgical treatment group showed hyponatremia (serum Na+ level less than lower normal range; 11.6% vs. 38.1%, p=0.01) or LDH level above upper normal range (5.0% vs. 42.8%, p<0.01); there was no significant difference in the number of patients whose CRP level increased above upper normal range (1 mg/dL) between the two groups (p=0.08). Unlike CRP, the absolute value of serum creatinine level was not significantly different between the groups; significantly more patients in surgical treatment group showed increased serum creatinine level above the upper normal range (1.2 mg/dL) than in medical treatment group (21.6% vs. 47.6%, p=0.04). A total of 98.3% of patients recovered in the medical treatment group, while only 52.4% recovered in the surgical treatment group with 47.6% of mortality. Other factors such as age, gender, underlying medical illness, colonic involvement site, and laboratory findings at admission did not show any difference between the groups (Tables 2, 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Presentations at Admission (II)

Values are presented as number (%).

SBP, systolic blood pressure; Cr, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein.

a)p-value was calculated by chi-square test; b)Cut-off value is upper normal limit used in Chonnam National University Hospital.

Clinical factor analysis associated with surgical treatment

We could not find a significant factor associated with surgical treatment by multivariate regression analysis determining clinical factors requiring surgical treatment than medical treatment. Abdominal rebound tenderness, however, was found as the most important clinical factor associated with surgical treatment (relative risk, 23.50).

DISCUSSION

IC is the most common bowel ischemic disease without specific symptom or diagnostic tool, which is why medical doctors' aggressive diagnostic course and doubt is important to clarify the incidence rate of IC in general population. The incidence rate of IC at the moment is reported roughly around 6.1 to 47 cases per 100,000 person-years in literature.8

IC has various clinical courses from recovering with medical treatment to requiring surgical treatment due to full-thickness colon necrosis.9 The initial course to find an appropriate treatment is to identify clinical, biochemical, colonoscopic or radiologic factors for screening of patient group who requires more aggressive treatment such as surgery rather than medical treatment. There is only a few studies, however, investigating this issue. This study was performed to find difference in clinical factors between medical and surgical treatment group in IC patients.

IC is well-known to occur mostly in elderly people. The mean age of IC patients was reported, in some studies, to be older in surgical treatment group than in medical treatment group,10 although neither in this study nor plenty of reports on severity of IC found any statistically significant difference in mean age between the two treatment groups.1,4,7,11-14 Several study results also reported that IC is a more common disease in female patients but a poorer prognostic factor in male patients. We could not find in this study, however, any statistical difference in gender or frequency between the two groups.7

Patients with history of hypertension, DM, coronary heart disease, congestive heart disease, hyperlipidemia and administration of vasoactive medicine were reported in many studies to show high frequency of IC incidence. This study also found similar pattern with hypertension (29.6%) and DM (21.0%) as the most common risk factor, followed by coronary heart disease, liver cirrhosis and cerebrovascular disease (n=5, 6.2% each), congestive heart disease (n=2, 2.5%), and ESRD (n=1). Studies report, however, different results on clinical course of IC according to underlying disease. For instance, studies on contributing factors of clinical course and time to admission reported that patients with DM took statistically longer time before admission.4 Studies on clinical course of chronic renal disease and IC reported that ESRD patients on hemodialysis showed severe clinical course requiring surgical treatment and longer mean time to admission.14 From 81 IC patients enrolled in this study, only 1 patient was receiving hemodialysis, who achieved recovery after medical treatment. Other underlying diseases also did not show any significant difference between medical and surgical treatment groups. Serum creatinine level was slightly higher in surgical treatment group than in medical treatment group, although not statistically significant (1.15±0.89 vs. 1.51±1.06, p=0.18). The relative risk of patients with increased serum creatinine level above normal range to receive surgical treatment was 2.937 (p=0.04), indicating close relationship between renal function and prognosis in patients with symptom development of admission, although we could not find prognostic relation between chronic renal disease and IC. Such change in renal function index is considered to reflect that IC was progressed as a secondary change to dehydration.15

In the past, barium study was preferred as a diagnostic tool for IC. Recently, however, colonoscopy or abdominal CT is more commonly selected as a major diagnostic tool. Colonoscopy has the advantage that colonoscopist can directly observe the colonic mucosa, whereas abdominal CT is good when observing bowel wall and abdominal vascular status at the same time.15-17 The medical treatment group in this study was diagnosed as IC mostly by colonoscopy (85.0%), whereas all cases in surgical treatment group received abdominal IC scanning and colonoscopy was performed in only 5 cases (8.9%). It is speculated that, compared to the medical treatment group showed only mild clinical course, many patients in the surgical treatment group showed severe clinical course making their general condition unsuitable for colonoscopy.

Symptoms of IC include abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, bowel movement change, or hematochezia.15 Vomiting is a risk factor of surgical treatment, but hematochezia was reported to be associated with mild clinical course in this study, which is comparable to other studies on IC severity.1,4,7,11-14,18 This reflects that the degree of colon injury depends on the presence of ischemia, consistent with the fact that necrotic colitis patients show vomiting more often than non-necrotic colitis patients due to rapid colonic wall full-thickness necrosis.19

Surgical treatment group showed high frequency of tachycardia and systolic hypotension at admission, abdominal tenderness or rebound tenderness at physical examination, and CRP elevation for initial laboratory finding, all indicating poor prognostic factors. This reflects that rapid inflammatory change in IC induced hemodynamic unstability and colonic wall full-thickness necrosis as secondary changes, suggesting possible progression to bowel perforation and peritonitis thereof.12 Patients who were progressed to colonic necrosis or complicated with peritonitis due to the necrosis are predicted to show leukocytosis due to inflammation, electrolyte or acid-base imbalance due to dehydration, or elevation of amylase, AST, or LDL level due to muscle injury. Studies actually found hyponatremia or elevated LDH level as poor prognostic factors of surgical treatment. This study also found hyponatremia or elevated LDH level at admission in surgically-treated group, but other laboratory findings was not different between the two treatment groups.12,18

As for the prognosis by involvement site, right lesion was generally more common and associated with worse prognosis.7,13 Other domestic reports, however, did not find any significant relationship between right colon involvement and poor prognosis as this study, which is why further studies are required.

There are some limitations in this study. First, being a retrospective analysis, we could not make clear definition about medical treatment group and surgical treatment group, or identify risk factors such as smoking history or drug history affecting vessels of patients. Second, we may not exclude the possibility of diagnostic error, because the study relied on colonoscopy or abdominal CT scan for the diagnosis of IC and did not confirm pathologic findings. Third, we tried to find clinical factors associated more with surgical treatment than medical treatment, but the sample size was not big enough for multivariate analysis and only the univariate analysis showed similar result with other studies. Even so, this study has implication for being the first report that compared clinical characteristics between medical treatment and surgical treatment, and warrants further study with larger sample size in the future.

In conclusion, IC patients with initial symptoms such as the absence of hematochezia, vomiting, abdominal tenderness, abdominal rebound tenderness, tachycardia, systolic hypotension, increased serum LDH, creatinine or CRP level indicates poor prognosis requiring surgical treatment. When patients suspected of IC shows initial clinical factors suggesting poor prognosis requires early aggressive therapy.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Do BH, Jeon SW, Kim SG, et al. An analysis based on hospital stay in ischemic colitis. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;33:140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cha SB, Park SH, Cho SH, et al. Analysis of 15 cases of ischemic colitis induced by increased abdominal pressure. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;16:952–961. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin NC, Kim YJ, Song YA, et al. Clinical features of ischemic colitis: related to age, constipation, irritable bowel syndrome. Chonnam Med J. 2008;44:144–150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung SH, Lee KM, Ji JS, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in ischemic colitis. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;36:349–353. [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald PH. Ischaemic colitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:51–61. doi: 10.1053/bega.2001.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scharff JR, Longo WE, Vartanian SM, Jacobs DL, Bahadursingh AN, Kaminski DL. Ischemic colitis: spectrum of disease and outcome. Surgery. 2003;134:624–629. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee TC, Wang HP, Chiu HM, et al. Male gender and renal dysfunction are predictors of adverse outcome in nonpostoperative ischemic colitis patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e96–e100. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d347b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandt LJ. Bloody diarrhea in an elderly patient. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:157–163. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bower TC. Ischemic colitis. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73:1037–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pla Martí V, Alós Company R, Ruiz Carmona MD, Solana Bueno A, Roig Vila JV. Experience and results on the surgical and medical treatment of ischaemic colitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2001;93:501–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn SE, Lee HL, Cho SC, et al. Is end stage renal disease a poor prognosis factor of ischemic colitis? Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Añón R, Boscá MM, Sanchiz V, et al. Factors predicting poor prognosis in ischemic colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4875–4878. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i30.4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandt LJ, Feuerstadt P, Blaszka MC. Anatomic patterns, patient characteristics, and clinical outcomes in ischemic colitis: a study of 313 cases supported by histology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2245–2252. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seok SJ, Kim KJ, Son BS, et al. Clinical features of ischemic colitis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Korean J Nephrol. 2009;28:595–602. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryu KH, Shim KN, Jung SA, et al. Clinical features of ischemic colitis: a comparision with colonoscopic findings. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;33:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. AGA technical review on intestinal ischemia. American Gastrointestinal Association. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:954–968. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taourel P, Aufort S, Merigeaud S, Doyon FC, Hoquet MD, Delabrousse E. Imaging of ischemic colitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008;46:909–924. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paterno F, McGillicuddy EA, Schuster KM, Longo WE. Ischemic colitis: risk factors for eventual surgery. Am J Surg. 2010;200:646–650. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barouk J, Gournay J, Bernard P, Masliah C, Le Neel JC, Galmiche JP. Ischemic colitic in the elderly: predictive factors of gangrenous outcome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:470–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]