Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The retroperitoneum can host a wide spectrum of pathologies, including a variety of rare benign tumours and malignant neoplasms that can be either primary or metastatic lesions. Retroperitoneal tumours can cause a diagnostic dilemma and present several therapeutic challenges because of their rarity, relative late presentation and anatomical location, often in close relationship with several vital structures in the retroperitoneal space.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed. Relevant international articles published in the last ten years were assessed. The keywords for search purposes included: retroperitoneum, benign, sarcoma, neoplasm, diagnosis and surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy. The search was limited to articles published in English. All articles were read in full by the authors and selected for inclusion based on relevance to this article.

RESULTS

Tumours usually present late and cause symptoms or become palpable once they have reached a significant size. Retroperitoneal tumours are best evaluated with good quality cross-sectional imaging and preoperative histology by core needle biopsy is required when imaging is non-diagnostic. Sarcomas comprise a third of retroperitoneal tumours. Other retroperitoneal neoplasms include lymphomas and epithelial tumours or might represent metastatic disease from known or unknown primary sites. The most common benign pathologies encountered in the retroperitoneum include benign neurogenic tumours, paragangliomas, fibromatosis, renal angiomyolipomas and benign retroperitoneal lipomas.

CONCLUSIONS

Complete surgical resection is the only potential curative treatment modality for retroperitoneal sarcomas and is best performed in high-volume centres by a multidisciplinary sarcoma team. The ability completely to resect a retroperitoneal sarcoma and tumour grade remain the most important predictors of local recurrence and disease-specific survival.

Keywords: Retroperitoneal, Sarcoma, Soft tissue sarcoma, Liposarcoma

The retroperitoneum can host a wide spectrum of pathologies, including a variety of rare benign tumours and malignant neoplasms that can be either primary or metastatic lesions. Malignant tumours of the retroperitoneum occur four times more frequently than benign lesions.1 Sarcomas comprise a third of retroperitoneal tumours. Soft tissue sarcomas are rare tumours, with retroperitoneal sarcomas expected to compose approximately 15% of the 2,000 cases of soft tissue sarcomas anticipated in England and Wales each year.2 In the UK there are estimated to be between 250 and 300 new diagnoses of retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS) each year. The retroperitoneum represents the second most common site of origin of malignant mesenchymal tumours after the lower extremities.3 Retroperitoneal tumours present several therapeutic challenges because of their relative late presentation and anatomical location (Fig 1).4 This review highlights the presentation, evaluation and initial management of patients presenting with retroperitoneal tumours and the surgical management of RPS.

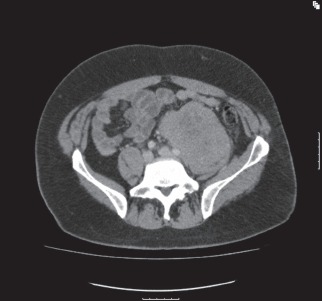

Figure 1.

CT of a 35-year-old male showing a large left-sided retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma. The tumour weighed 15kg at resection.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed. Relevant international articles published in the last ten years were assessed. The keywords for search purposes included: retroperitoneum, benign, sarcoma, neoplasm, diagnosis and surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy. The search was limited to articles published in English. All articles were read in full by the authors and selected for inclusion based on relevance to this article.

Background

The retroperitoneum represents a complex potential space with multiple vital structures bounded anteriorly by the peritoneum, ipsilateral colon and mesocolon, pancreas, liver or stomach. The posterior margins are by large composed of the psoas, quadratus lumborum, transverse abdominal and iliacus muscles but, depending on the tumour location and size, may be formed by the diaphragm, ipsilateral kidney, ureter and gonadal vessels. Similarly, the medial boundaries may include the spine, paraspinous muscles, the inferior vena cava (for right-sided tumours) and the aorta (for left-sided tumours). The lateral margin is formed by the lateral abdominal musculature and, depending on tumour location, may include the kidney and colon. Superiorly, retroperitoneal tumours may be in contact with the diaphragm, the right lobe of the liver, the duodenum, the pancreas or the spleen. The inferior margin may relate to the iliopsoas muscle, the femoral nerve, the iliac vessels or pelvic sidewall.5

Due to the inaccessibility of the region and since these tumours often give no or non-specific symptoms until they have reached a substantial size, they are usually large at presentation.4 Sarcomas comprise a third of retroperitoneal tumours, with two histological subtypes predominating, namely liposarcoma (70%) and leiomyosarcoma (15%).6 Other retroperitoneal neoplasms include primary lymphoproliferative tumours (Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin lymphoma) and epithelial tumours (renal, adrenal, pancreas) or might represent metastatic disease from known or unknown primary sites (germ cell tumours, carcinomas, melanomas) (Fig 2).6 Benign tumours can cause concern and are often an incidental finding during an investigation for unrelated symptoms. They may be referred on suspicion of being a sarcoma. The most common benign pathologies encountered in the retroperitoneum include benign neurogenic tumours (schwannomas, neurofibromas), paragangliomas (functional or non-functional), fibromatosis, renal angiomyolipomas and benign retroperitoneal lipomas (Figs 3 and 4).1

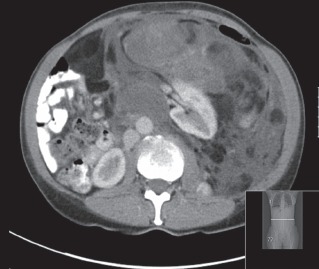

Figure 2.

Lobulated mass in left iliac fossa that is encasing the distal aorta, bifurcation and left common iliac vessels. A core needle biopsy was consistent with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Figure 3.

CT demonstrating a well circumscribed heterogeneous solid mass arising from the left posterior hemipelvis involving the body of the first and second sacral segments from which it is arising. There is scalloping with smooth erosion of the S1 vertebral body on the left, suggesting that this is a longstanding process. A core needle biopsy confirmed this mass to be a benign schwannoma.

Figure 4.

Coronal (A) and cross-section (B) CT of a 26-year-old male showing a huge central pelvic mass that arises from the pelvis and extends into the abdomen to the level of the epigastrium. This mass measured 23cm × 19cm × 11cm in diameter. It is displacing bowel loops into the upper abdomen. It is compressing but not obstructing or invading the inferior vena cava and both common iliac and external iliac vessels lie separately from it. The histology was consistent with fibromatosis/desmoid tumour.

Presentation

Most patients who have a retroperitoneal tumour present with abdominal swelling/increase in girth, early satiety and abdominal discomfort, and most patients have a palpable mass.7 Many benign lesions are discovered as an incidental finding during imaging for unrelated symptoms.8 Although the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts are often displaced, they are rarely invaded and gastrointestinal or urinary symptoms are unusual.9

Initial evaluation

The imaging investigation of choice is contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. The size, location, relationship to adjacent organs and presence or absence of metastases can be determined. Liposarcomas demonstrate a characteristic appearance with a predominantly fatty component causing displacement of the kidney, colon and other organs. The CT attenuation reflects the histological subtype, specifically the amount of fat in the mass, with lower grade, well differentiated liposarcoma entirely or predominantly fatty while higher grade lesions show increased density with solid attenuation and contrast enhancement (Figs 5 and 6).4,6 The performance of a preoperative biopsy for these lesions is controversial and in patients where the radiological characteristics of retroperitoneal liposarcoma are not in doubt, a preoperative biopsy is not required.

Figure 5.

CT of a 42-year-old male demonstrating a huge, well differentiated liposarcoma arising from the left retroperitoneum and anteriorly to the left kidney, and extending into the pelvis. The tumour extends superiorly to the left hemidiaphragm, where it passes the midline with displacement of small and large bowel loops into the right flank. The CT attenuation reflects the histological subtype, specifically the amount of fat in the mass, with low-grade, well differentiated liposarcoma entirely or predominantly fatty.

Figure 6.

CT of a left dedifferentiated retroperitoneal liposarcoma causing displacement of the left kidney. The CT attenuation reflects the histological subtype with higher grade lesions showing increased density with solid attenuation and contrast enhancement.

Because RPS accounts for only a third of retroperitoneal tumours, other diagnoses must be considered when the radiological appearance is not typical of a retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Metastatic testicular neoplasm should be considered in younger male patients with a midline retroperitoneal lesion and investigated by testicular ultrasound and tumour markers (alpha-fetoprotein and β-human chorionic gonadotrophin). In patients presenting with a retroperitoneal tumour, where the radiological appearance is uncertain or when the radiological appearance suggests a pathology where neoadjuvant treatment may be appropriate as induction therapy (eg gastrointestinal stromal tumour, Ewing's sarcoma, teratoma), a preoperative biopsy is mandatory (Figs 7 and 8). A preoperative core needle biopsy is safe and when indicated offers the opportunity of identifying a chemo-sensitive tumour or a benign tumour that may not necessarily require resection.7,10,11 Additionally, if a tumour is deemed unresectable or the patient has distant metastases, a core needle biopsy may be indicated to confirm the diagnosis and to enable consideration of alternative therapy. Intra-abdominal lymphoma is not uncommon and may present as a midline mass, which can displace or encase the aorta, cava or iliac vessels. The histological diagnosis can often be made on percutaneous core needle biopsy.11

Figure 7.

CT of an 80-year-old male showing a central abdominal mass probably arising from within the mesentery or a small bowel loop. A core needle biopsy confirmed a gastrointestinal stromal tumour with a mutation found in exon 11 of the KIT gene. The patient was commenced on imatinib.

Figure 8.

CT of a 27-year-old male showing a left retroperitoneal mass closely applied to the aorta. A core needle biopsy was consistent with a diagnosis of Ewing's sarcoma and genetic analysis demonstrated a translocation involving the EWSR1 gene. The patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and <10% viable tumour was found on post-resection histology.

Benign neurogenic tumours grow to a significant size before becoming palpable or symptomatic. Most schwannomas are well circumscribed masses with smooth, regular margins with central cystic degeneration, displacing rather than invading local structures. In the abdominal retroperitoneum, nerve sheath tumours may be located anterior to the psoas muscle arising from the sympathetic chain or femoral nerve while those located in the pre-sacral space arising from the sacral nerve roots often show expansion of the exit foramina. Management options for retroperitoneal schwannomas include radiological surveillance in asymptomatic patients or surgical resection in symptomatic patients.8

Surgical management

Complete surgical resection is the only potential curative treatment modality for RPS but local recurrence occurs in a large proportion of patients and is responsible for as many as 75% of sarcoma-related deaths. The prognostic factors that are known to govern local recurrence and overall survival in RPS are complete macroscopic excision, tumour grade, multifocality and histological subtype.4,9,12-17 RPS carries a much worse prognosis than extremity sarcomas with five-year local recurrence-free survival after complete resection ranging between 55% and 78%, and five-year overall survival between 39% and 68%. This is because they are generally larger and arise in an anatomically complex and surgically inaccessible site with surrounding vital structures limiting wide margins. They are often not amenable to conventional radical radiotherapy.2,4,9,12-17 The likelihood of a complete margin-negative surgical resection depends on tumour biology, and invasion of adjacent visceral organs and vascular structures, and may be influenced by surgical experience and management in high-volume centres.12-20

Resection of adjacent involved organs is frequently required and rates of resection of adjacent viscera are reported in large series from 34% to 93% while macroscopic clearance was obtained in 55–93% (Fig 9).12-20 Our unit's surgical approach involves a low threshold for organ resection to obtain a complete clearance of all macroscopic disease. This is performed as an en bloc resection of the sarcoma and contiguous organs that are macroscopically involved by tumour or enveloped by the tumour in order to gain complete macroscopic clearance. No attempt is made to resect organs that merely lay adjacent to the tumour and are not involved. We reported a resection of adjacent organ rate of 65% while macroscopic clearance was achieved in 85% of patients. The most common organs requiring resection are the colon, kidney, pancreas and spleen.4

Figure 9.

CT of a radiation-induced right retroperitoneal sarcoma, involving the ribs and diaphragm. Resection included a right nephrectomy, liver wedge resection, resection of the diaphragm and chest wall with mesh reconstruction.

Two retrospective European studies reported the role of liberal visceral en bloc resection in an attempt to include an envelope of normal tissue around the tumour to minimise the marginality of the resection in the hope of improving outcome.13,14 A number of major criticisms were raised in response to these two reports, based in part on the difficulty in drawing conclusions from multicentre retrospective series.5 It is also questionable whether a selective approach to resection of some ‘disposable’ organs (colon, kidney, psoas) adjacent to the tumour, while preserving other critical structures (inferior vena cava, aorta, superior mesenteric artery, liver) that also lie in contact with the tumour, could succeed in improving the overall survival. There is no reason to suggest that any one of the organs forming the borders of the retroperitoneum is more critical in determining local failure than any other.5,13,14

Recurrent disease

Local recurrence is common for RPS and remains the major cause of death. Tumour biology reflected in tumour grade is a significant prognostic factor for patients with recurrent RPS; local recurrence rates are higher in patients with high-grade tumours and occur at an earlier interval compared with patients with low-grade tumours.9,15,16,21 Most reports on this subject are retrospective with different management strategies and variable results. CT is indicated when patients exhibit new symptoms or a mass is palpable on clinical examination. Further surgery is advised if the patient develops significant symptoms or if further delay will make eventual surgery more difficult.

The likelihood of obtaining negative margins is significantly lower at the time of local recurrence and each successive operation is more difficult than the last.6,9 Nevertheless, resection should be considered in symptomatic patients with first and subsequent local recurrence as it provides good palliation and a possible improved survival for selected patients.22 Palliative surgery (incomplete resection leaving unresectable tumour) for recurrent sarcomas of low or intermediate grade can be offered for symptom control and may improve quality of life.23,24

Radiotherapy

The high rate of local failure has prompted investigation of combined modality treatment (surgery with radiotherapy) in an attempt to lower the rate of local recurrence.25 Radiotherapy improves local control in extremity sarcomas and has become standard practice.26 However, RPS presents several radiotherapeutic challenges. These tumours are often adjacent to radiosensitive structures with low radiation tolerance. Retroperitoneal sarcomas compose a heterogeneous group of pathologies with variable radiosensitivity.

Several retrospective and observational studies have been published to evaluate the feasibility and outcome of pre-, intra- and postoperative radiotherapy in the management of RPS.27-31 The advantages of preoperative radiotherapy include: the tumour is clearly demarcated for radiotherapy planning, the tumour is displacing some of the radiosensitive adjacent organs and an equivalent therapeutic dose of radiotherapy may be lower in the preoperative setting. Postoperative radiotherapy makes it possible to select those patients at highest risk for recurrence based on the grade and margin status. However, in the postoperative setting, the adjacent organs will move into and become adherent to the tumour bed, increasing the risk of radiation-associated toxicities. In an attempt to reduce the radiation toxicities, studies have evaluated the treatment planning with conformal therapies such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy or the use of intraoperative radiotherapy.30,31

The paucity of randomised controlled trials and diverse variables in observational and retrospective studies make it impossible to define the exact and appropriate role of radiotherapy in the management of RPS. A European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer study of preoperative radiotherapy in RPS that will accrue patients from high-volume centres is at the planning stages.

Chemotherapy

Neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy for the majority of histological subtypes has not shown consistent evidence of a disease-free survival benefit although there may be certain situations where it is advantageous. For subtypes such as the Ewing family of tumours, for which chemotherapy is an essential part of primary management, chemotherapy has definitely improved survival. There is a role for agents such as doxorubicin and ifosfamide in the palliation of symptomatic advanced sarcoma. There is increasing specialisation of chemotherapy according to histological subtype, such as the use of taxanes for angiosarcoma, gemcitabine and docetaxel for leiomyosarcoma, and trabectedin for leiomyosarcoma and myxoid/round cell liposarcoma.32

Improving Outcomes

An important development in surgery during the last decade has been the concept of concentrating rare surgical conditions and complex operations in high-volume specialist centres.33,34 High surgeon volume and specialised centres are associated with improved patient outcome in major oncologic surgery including hepatobiliary/pancreatic surgery, oesophagogastric surgery and surgical oncology. This has also been investigated in sarcomas and the recommendation from a study comparing the outcome between low- and high-volume centres was that patients with large, high-grade and especially retroperitoneal tumours should be treated exclusively in high-volume centres to ensure both improved short-term surgical outcomes and superior long-term local recurrence and overall survival rates.20 Therefore, the treatment of RPS should be limited to a few experienced multidisciplinary units. This will also reflect favourably on training and research.

Research into tumour biology focuses on the molecular and genetic heterogeneity of sarcomas and will hopefully lead to the development of novel biological therapies to target the various molecular pathways, similar to the success demonstrated in treating gastrointestinal stromal tumours with a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor.

The appropriate role, dose and timing of radiotherapy in improving local control need to be established in randomised control trials.

Conclusions

The retroperitoneum can host a wide spectrum of rare pathologies, including benign and malignant tumours. Tumours usually present late and cause symptoms or become palpable once they have reached a significant size. Retroperitoneal tumours are best evaluated with good quality cross-sectional imaging and preoperative histology by core needle biopsy is required when imaging is non-diagnostic. Complete surgical resection is the only potential curative treatment modality for retroperitoneal sarcomas and is best performed in high-volume centres by a multidisciplinary sarcoma team. Local recurrence occurs in a large proportion of patients. The ability completely to resect a retroperitoneal sarcoma and tumour grade remain the most important predictors of local recurrence and disease-specific survival. Further research is required to define the role of radiotherapy and develop novel biological therapies to target the various molecular pathways.

References

- 1.Van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC. Soft tissue tumours of the retroperitoneum. Sarcoma. 2000;4:17–26. doi: 10.1155/S1357714X00000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes for People with Sarcoma: The Manual. London: NICE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th edn. St Louis, Missouri, US: Mosby; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss DC, Hayes AJ, Thway K, et al. Surgical management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97:698–706. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raut CP, Swallow CJ. Are radical compartmental resections for retroperitoneal sarcomas justified? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1,481–1,484. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark MA, Fisher C, Judson I, Thomas JM. Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:701–711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hueman MT, Herman JM, Ahuja N. Management of retroperitoneal sarcomas. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes MJ, Thomas JM, Fisher C, Moskovic EC. Imaging features of retroperitoneal and pelvic schwannomas. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:886–893. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuhaus SJ, Barry P, Clark MA, et al. Surgical management of primary and recurrent retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Br J Surg. 2005;92:246–252. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoeber I, Spillane AJ, Fisher C, Thomas JM. Accuracy of biopsy techniques for limb and limb girdle soft tissue tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:80–87. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0080-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss DC, Qureshi YA, Hayes AJ, et al. The role of core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of suspected soft tissue tumours. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:523–529. doi: 10.1002/jso.21600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis JJ, Leung D, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma: analysis of 500 patients treated and followed at a single institution. Ann Surg. 1998;228:355–365. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonvalot S, Rivoire M, Castaing M, et al. Primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: multivariate analysis of surgical factors associated with local control. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:31–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gronchi A, Lo Vullo S, Fiore M, et al. Aggressive surgical policies in a retrospectively reviewed single-institution case series of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:24–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.8871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anaya DA, Lahat G, Wang X, et al. Establishing prognosis in retroperitoneal sarcoma: a new histology-based paradigm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:667–675. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehnert T, Cardona S, Hinz U, et al. Primary and locally recurrent retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma: local control and survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan I, Park SZ, Donohue JH, et al. Operative management of primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a reappraisal of an institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2004;239:244–250. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000108670.31446.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brennan MF. Local recurrence in soft tissue sarcoma: more about the tumor, less about the surgeon. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1,528–1,529. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anaya DA, Lev DC, Pollock RE. The role of surgical margin status in retroperitoneal sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:607–610. doi: 10.1002/jso.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutierrez JC, Perez EA, Moffat FL, et al. Should soft tissue sarcomas be treated at high-volume centers? An analysis of 4205 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:952–958. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250438.04393.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisters PW. Resection of some – but not all – clinically uninvolved adjacent viscera as part of surgery for retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grobmyer SR, Wilson JP, Apel B, et al. Recurrent retroperitoneal sarcoma: impact of biology and therapy on outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibata D, Lewis JJ, Leung DH, Brennan MF. Is there a role for incomplete resection in the management of retroperitoneal liposarcomas? J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:373–379. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Dalen T, Hoekstra HJ, van Geel AN, et al. Locoregional recurrence of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: second chance of cure for selected patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:564–568. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raut CP, Pisters PW. Retroperitoneal sarcomas: combined-modality treatment approaches. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:81–87. doi: 10.1002/jso.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang JC, Chang AE, Baker AR, et al. Randomized prospective study of the benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:197–203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zlotecki RA, Katz TS, Morris CG, et al. Adjuvant radiation therapy for resectable retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: the University of Florida experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:310–316. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000158441.96455.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng M, Murphy J, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term outcomes after radiotherapy for retroperitoneal and deep truncal sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Youssef E, Fontanesi J, Mott M, et al. Long-term outcome of combined modality therapy in retroperitoneal and deep-trunk soft-tissue sarcoma: analysis of prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:514–519. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02942-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bossi A, De Wever I, Van Limbergen E, Vanstraelen B. Intensity modulated radiation-therapy for preoperative posterior abdominal wall irradiation of retroperitoneal liposarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alektiar KM, Hu K, Anderson L, et al. High-dose-rate intraoperative radiation therapy (HDR-IORT) for retroperitoneal sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krikelis D, Judson I. Role of chemotherapy in the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10:249–260. doi: 10.1586/era.09.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chowdhury MM, Dagash H, Pierro A. A systematic review of the impact of volume of surgery and specialization on patient outcome. Br J Surg. 2007;94:145–161. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Learn PA, Bach PB. A decade of mortality reductions in major oncologic surgery: the impact of centralization and quality improvement. Med Care. 2010;48:1,041–1,049. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f37d5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]