Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Elderly patients with oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer wishing to avoid surgery or those who are considered unsuitable for a general anaesthetic may be treated with primary endocrine therapy. We have reviewed all patients with ER-positive breast cancer who were initially treated with primary hormone therapy (PHT) at a district general hospital in south Wales and investigated their outcome in order to evaluate the appropriateness of this method of managing breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients with breast cancer who were initially treated with PHT between January 2002 and December 2008 were identified from a single consultant's prospectively maintained database. For each patient the Charlson co-morbidity index was calculated to give an estimate of ten-year survival. Patients who had died during the study period were identified from hospital and cancer registries.

RESULTS

A total of 83 cancers in 82 patients with a median age of 81 years (range: 62–93 years) were included. All cancers were ER-positive. Six patients (7%) had a greater than 50% chance of surviving ten years, calculated using the Charlson index. The median follow-up period was 24 months (range: 6–72 months). Twelve patients (15%) had disease progression while taking PHT. Twenty-three patients (28%) have died (median time from diagnosis to death of 10.5 months, range: 1–77 months). Two patients (2%) experienced disease progression within six months of starting PHT and the number of patients whose cancer progressed increased with increasing length of follow up. Fourteen patients (17%) eventually underwent a wide local excision under local anaesthetic.

CONCLUSIONS

PHT can be considered an effective treatment in this elderly, unfit population with the aim of stopping disease progression so that these patients die with their breast cancer, not of it.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Elderly patients, Charlson index, Hormone therapy

Almost half of all breast cancer in England occurs in women over the age of 70.1 This age group typically experiences greater co-morbidity than younger women and is less likely to tolerate a general anaesthetic.2 Older women with breast cancer are less likely to receive standard treatment such as axillary node surgery3 or radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery4 than younger women. However these patients still require control of their breast cancer.

Breast cancer may be a more indolent disease in old age.5 Elderly patients with oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer, who wish to avoid surgery or are considered too frail to undergo a general anaesthetic, are often treated with primary endocrine therapy. This treatment may be considered to be neoadjuvant with the aim of downstaging the tumour so that it becomes amenable to breast conserving surgery under local anaesthetic. Otherwise hormone therapy may be the only treatment given.

However, primary endocrine therapy is not without problems. Compliance with drug treatment is important when assessing the suitability of a patient for primary endocrine therapy, as is the ability to attend outpatient appointments for review of the response to treatment6 and which method of assessing tumour response (clinical measurement with callipers or radiological measurement with ultrasound or mammograms) is to be used. Traditionally, tamoxifen was used as the first-line agent in this treatment method. Nevertheless, there is evidence that breast cancers become resistant to its use with time6 and it has been largely superseded by third-generation aromatase inhibitors in this role. Again, these are not without problems and the ATAC (Arimidex® or tamoxifen alone or in combination) trial showed that when used in the adjuvant setting there were significantly more fractures overall when compared with tamoxifen, a source of considerable morbidity and mortality in the elderly.7

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of primary hormone therapy (PHT) in elderly, unfit patients with ER-positive breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

All patients with ER-positive breast cancer initially treated with PHT at a district general hospital in South Wales between January 2002 and December 2008 were included in the study. Suitable patients were identified from a single consultant breast surgeon's prospectively maintained database, which included all follow-up information from subsequent clinic visits.

Patients were followed up at six weeks after diagnosis and then again at three months, followed by six-monthly intervals. (However, by the nature of the study population, missed clinic appointments due to illness were frequent.) Tumour size was recorded clinically using callipers or using ultrasound for impalpable lesions and modified World Health Organization criteria were used to evaluate the tumour response to hormone therapy.6

For each patient the Charlson index of co-morbidity8 was calculated. The Charlson index is a score for evaluating prognosis based on age and co-morbid conditions. From a combined score an estimate of ten-year survival is given.

Patients who had died during the study period were identified from hospital and cancer registries. The patients' death certificates were then obtained from the local registrar of births and deaths.

Results

A total of 83 cancers in 82 patients were included (one patient had bilateral disease). Three patients initially declined surgery when offered; the remaining patients were not considered suitable for surgery. Patients were not offered surgery either because it was felt they would not tolerate a general anaesthetic (because of extensive cardiorespiratory or renal co-morbidity) or surgery was felt to be inappropriate because of severe neurological co-morbidity, extremes of old age or co-exisiting advanced malignancy. If there was any doubt as to a patient's ability to tolerate a general anaesthetic, an opinion was sought from an experienced senior anaesthetic consultant.

The study group had a median age of 81 years (range: 62–93 years). The median follow-up period was 24 months (range: 6–72 months). The majority of cancers (72%) were of the invasive ductal type with smaller numbers seen of invasive lobular (13%) and mixed cancers (5%). All cancers were ER positive, with 75 (90%) being strongly positive.

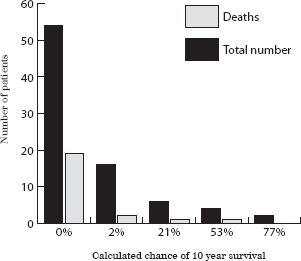

The probability of ten-year survival for all patients was retrospectively calculated using the Charlson index of co-morbidity and age. A total of 28 patients (34%) had a greater than 2% chance of surviving 10 years. However, only six (7%) had a greater than 50% chance of surviving ten years. (The majority of patients in the group with a >50% chance of ten-year survival had some form of dementia and were not considered suitable for surgery by the surgical team and patients' families.) Unsurprisingly, 19 of a total of 23 deaths (83%) occurred in the group of patients for whom there was a 0% likelihood of surviving ten years (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Probability of ten-year survival calculated using the Charlson index of co-morbidity and age

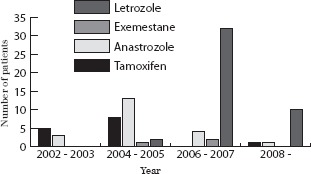

Overall, 14 patients (17%) were initially treated with tamoxifen, 21 (26%) with anastrozole, 3 (4%) with exemestane and 44 (54%) with letrozole (Fig 2). During the initial part of the study patients were started on tamoxifen while later on they were started on anastrozole (or exemestane if visceral metastases were diagnosed at initial presentation). Towards the end of the time period studied, patients were predominantly started on letrozole as this became the sole licensed drug for use in this setting. Over a six-year period of follow-up only 12 patients (15%) had disease progression while taking PHT (Fig 3). Of these, five patients (42%) had been initially treated with anastrozole, three were taking tamoxifen (25%) and four letrozole (33%). Although none of the three patients treated with exemestane had disease progression, two had died within four months of diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Initial primary hormone therapy

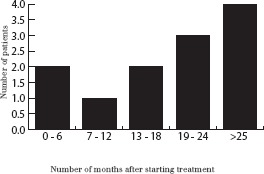

Figure 3.

Number of patients with disease progression while taking primary hormone therapy

Twenty-three patients (28%) from the treatment group have subsequently died, with a median time from diagnosis to death of 10.5 months (range: 1–77 months); three had metastatic disease at presentation. Breast cancer was recorded in part 1a of the death certificate in ten patients (43%) and in part 1b or 2 in a further five patients (22%).

Two patients (2%) experienced disease progression within six months of starting PHT and the number of patients whose cancer progressed increased with increasing length of follow up, reaching a peak of four patients (5%) at more than 25 months of follow up (Fig 3). Eight of those patients initially taking anastrozole (38%), six of those taking tamoxifen (43%) and nine taking letrozole (20%) were subsequently switched to a different endocrine therapy for static or progressive disease, or due to unwanted side effects.

Fourteen patients (17%) eventually underwent a wide local excision under local anaesthetic (LA). None of these patients had axillary surgery. Of these fourteen, four (29%) had initially been started on tamoxifen, two (14%) on anastrozole and eight (57%) on letrozole. Two patients (14%) who had surgery have since died, one of metastatic breast cancer after two months and one following perforated diverticular disease after 36 months. None of the patients who had a wide local excision under LA had histologically involved margins. A summary of the patients' outcome is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patient outcome while taking primary hormone therapy

| Initial hormone treatment | Number of patients | Number with disease progression | Number requiring change in hormone treatment | Number undergoing surgery | Number died |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letrozole | 44 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 10 |

| Tamoxifen | 14 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Exemestane | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Anastrozole | 21 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 7 |

| Total | 82 | 12 | 23 | 14 | 23 |

Discussion

Previous studies comparing PHT alone with surgery followed by adjuvant hormone therapy have yielded mixed results. Mustacchi et al compared five years of tamoxifen alone with surgery followed by five years of tamoxifen and showed that overall breast cancer survival rates were comparable between groups but rates of local progression were far higher in the ‘tamoxifen alone’ group.9 Similar results in terms of comparable survival but improved local control were shown by Kenny et al comparing wedge mastectomy alone with tamoxifen.10 However, Fennessy et al showed that omitting primary surgery and relying on tamoxifen alone resulted in increased rates of disease progression and mortality in elderly women.5 It should be noted that patients were randomised to either treatment arm regardless of ER status in all of the previous studies and women with ER-negative disease will derive no benefit from tamoxifen.

The majority of patients involved in this study were taking a third generation aromatase inhibitor and there is evidence to support their use over tamoxifen. A study from the Edinburgh breast unit involved using neoadjuvant letrozole in 150 women with large operable or locally advanced breast cancer and showed complete response rates of 36% after 12 months of treatment.11 In a small study of only 12 patients, 10 had a greater than 50% reduction in tumour volume with neoadjuvant exemestane12 and in a French study of 38 women given 4–5 months of exemestane prior to surgery, 5.9% had a complete response and 64.7% a partial response.13

Surgical intervention is still the treatment of choice in elderly women with breast cancer. However, this study has shown that PHT can achieve good short- and medium-term tumour control rates and can be considered as an alternative treatment in women who are unfit for or unwilling to have an operation. Letrozole is now the authors' preferred primary hormone treatment although further data from long-term follow up on rates of disease progression are required.

The authors recommend that if PHT is to be used there should be clear documentation of why surgery was not offered recorded in the case notes. The Charlson index is a valuable tool to aid in the best treatment decision making process for these patients and is readily available on the internet14 to use in the clinic or multidisciplinary team meetings. If there is any doubt as to a patient's suitability for general anaesthetic he or she should be reviewed by a senior anaesthetist.

LA excision has a role to play, particularly in patients with ER-negative disease or progressive disease on PHT. Although it is yet to be used in this population, novel treatments such as focused microwave thermotherapy15 may be useful in the treatment of elderly, unfit patients with breast cancer in the future.

Conclusions

The effective treatment of elderly, unfit patients with breast cancer remains difficult and challenging. In this group mortality from all causes is high and the patients themselves are often unfit for a general anaesthetic or unwilling to consider the prospect of an operation.

However, good short- and medium-term tumour control rates can be achieved with primary endocrine therapy. These patients require regular follow-up and vigilance in detecting disease progression from the surgical team. LA excision is generally well tolerated and it may be the only way of achieving local disease control.

PHT can be considered an effective treatment in this elderly, unfit population and the aim should be to stop disease progression so that these patients die with their breast cancer, not of it.

References

- 1.Office for National Statistics. Cancer statistics registrations: registrations of cancer diagnosed in 2003, England. Series MB1 no. 34. London: ONS; 2005. Table 8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA. 2001;285:885–892. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyld L, Garg DK, Kumar ID, et al. Stage and treatment variation with age in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: compliance with guidelines. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1,486–1,491. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gennari R, Curigliano G, Rotmensz N, et al. Breast carcinoma in elderly women: features of disease presentation, choice of local and systemic treatments compared with younger postmenopausal patients. Cancer. 2004;101:1,302–1,310. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fennessy M, Bates T, MacRae K, et al. Late follow-up of a randomized trial of surgery plus tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone in women aged over 70 years with operable breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:699–704. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macaskill EJ, Renshaw L, Dixon JM. Neoadjuvant use of hormonal therapy in elderly patients with early or locally advanced hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Oncologist. 2006;11:1,081–1,088. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-10-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:60–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustacchi G, Ceccherini R, Milani S, et al. Tamoxifen alone versus adjuvant tamoxifen for operable breast cancer of the elderly: long-term results of the phase III randomized controlled multicenter GRETA trial. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:414–420. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenny FS, Robertson JF, Ellis IO, et al. Long-term follow-up of elderly patients randomized to primary tamoxifen or wedge mastectomy as initial therapy for operable breast cancer. Breast. 1998;7:335–339. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renshaw L, Murray J, Young O, et al. Is there an optimal duration of neoadjuvant letrozole therapy? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88(Suppl 1):S36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller WR, Dixon JM. Endocrine and clinical endpoints of exemestane as neoadjuvant therapy. Cancer Control. 2002;9(2) Suppl:9–15. doi: 10.1177/107327480200902S02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tubiana-Hulin M, Spyratos F, Becette V, et al. Phase II study of neoadjuvant exemestane in postmenopausal patients with operable breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;82(Suppl 1):S106. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson Comorbidity Index Score Calculator. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/supplementary/1471-2407-4-94-S1.xls (cited March 2011)

- 15.Dooley WC, Vargas HI, Fenn AJ, et al. Focused microwave thermotherapy for preoperative treatment of invasive breast cancer: a review of clinical studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1,076–1,093. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0872-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]