Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a common condition (250 per million population per year) with significant associated morbidity and mortality.1 Surgery is the only curative option for PHPT; results from medical treatment remain disappointing.2 The aim of this study was to evaluate the referral patterns of patients with PHPT and identify the number of missed cases with a biochemical diagnosis of PHPT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All chemistries for Worcestershire were performed and analysed at the Worcestershire Royal Hospital. Patients with chronic renal failure were identified and excluded. Routes of patient referral were identified and missed cases documented. General practitioners (GPs) were contacted by letter for all patients not referred or treated. Outcomes of diagnosis and specialist assessment were recorded.

RESULTS

A total of 102 cases of PHPT were identified: 64 (62.7%) remained untreated and without a specialist referral in place, 36 (35.3%) had undergone parathyroidectomy and 2 (2.0%) were being monitored. The GP response rate was 90% (46/51). Of these, 30 (65%) were subsequently referred, 9 (20%) underwent repeat tests with a view to referral and 7 (15%) were lost to follow up.

CONCLUSIONS

A significant proportion of patients with PHPT remain in the community untreated and having not seen a specialist. All patients should be referred to a specialist for assessment and consideration of surgical treatment and follow-up. Improvements in GP education and referral systems are required if patients are to benefit.

Keywords: Parathyroidectomy, Hyperparathyroidism, Referral, Primary, Asymptomatic

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a relatively common condition with recognised diagnostic criteria and treatment options available. In the 1980s the incidence of PHPT in nearby Birmingham was 250 cases per million population per year.1 Diagnosis has changed significantly over the past 40 years since the advent of multichannel biochemical analysers. Nowadays only 20% of patients present with the classic symptoms of urinary calculi, bone symptoms (pain or fracture), hypercalcaemic crisis or neuropsychiatric symptoms.3 Most patients will be identified by aberrant calcium levels with inappropriately high parathyroid hormone secretion. Such patients are often classified as ‘asymptomatic’ but on further questioning may report symptoms of fatigue, weakness and reduced functional capacity, myalgia, confusion and depression, constipation, polydipsia and polyuria.

Moreover, PHPT leads to significant morbidity and mortality associated with cardiac and valvular calcification, and malignancy.4-6 Once diagnosed, patients should be referred to an endocrinologist or surgeon for further assessment and management.7 The aim of this study was to evaluate the referral patterns of patients with PHPT and identify the incidence of missed patients with a biochemical diagnosis of PHPT.

Methods

All serum and urine biochemical samples from Worcestershire (population 550,000) are analysed at a single hospital laboratory site (Worcestershire Royal Hospital). All patients with serum parathyroid hormone studies between April 2006 and March 2009 were looked at and those with a biochemical diagnosis of PHPT identified.

Case notes for these patients were drawn and treatments classified according to outcome (parathyroidectomy, active monitoring, biochemical diagnosis but no management plan in place). General practitioners (GPs) of patients in whom no referral or treatment plan was evident were contacted by letter and the resulting outcome documented.

Results

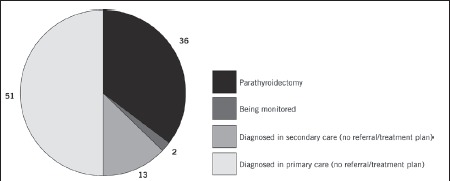

A total of 102 cases of PHPT were identified. Of these, 64 (62.7%; 13 diagnosed in hospital and 51 in the community) had no referral or treatment plan, 36 (35.3%) had undergone parathyroidectomy and 2 (2.0%) were being actively monitored. Figure 1 illustrates the referral and treatment outcomes following diagnosis. Histology reports identified adenoma and/or hyperplasia in all patients who underwent parathyroidectomy.

Figure 1.

Referral and treatment outcomes following diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism

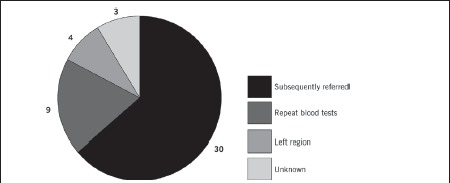

The GP response rate was 90% (46/51). As a result of the letters, 30 (65.2%) patients were subsequently referred and 9 (19.6%) underwent repeat blood tests on the advice of an endocrinologist. Four patients (8.7%) had left the region while the outcome of three (6.5%) remained unknown. Two patients from the primary care group are currently awaiting surgery. Figure 2 illustrates the referral and treatment outcomes after follow-up letters. The incidence of missed cases of PHPT was almost 2 in 3 patients (62.7%).

Figure 2.

Referral and treatment outcomes after follow-up letters to general practitioner

Discussion

In our series a significant proportion of patients were diagnosed by GPs, with half of the PHPT population (50%) remaining in the community without a treatment plan in place or specialist referral made. Ready et al described a similar situation in our wider region, the West Midlands, where long delays in treatment were experienced as a result of absent or ill-directed specialist referral.8 Almost 20 years later, little progress has been made in the referral patterns of GPs. The number of patients diagnosed in secondary care without a referral or treatment plan (13) is significantly less than that diagnosed by GPs (51) but nevertheless also of concern. The reasons for this are multifactorial and include the patients' age, co-morbidity, a failure to act on abnormal results and inadequate knowledge of referral guidelines.9,10

Parathyroidectomy for PHPT is curative and extremely successful, with cure rates exceeding 95% and a low proportion of postoperative complications.11 With the advent of advanced imaging (sestamibi scan), minimally invasive techniques and day-case hospital stay, low morbidity and procedure-related costs are also achievable.12 Surgery is recommended for all patients with evidence of symptomatic disease.10 For those with asymptomatic PHPT, the recommendations for surgery can be seen in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Recommended indications for surgery in asymptomatic patients with hyperparathyroidism20

| Age | <50 years |

| Serum calcium | >0.25mmol/l above upper limit of normal |

| Creatinine clearance | Reduced by 30% or more (eGFR <60ml/min) |

| Bone mineral density | T score <-2.5 (at any site) |

| Follow up | Unlikely or impractical |

However, distinguishing patients with truly asymptomatic disease from patients with mild PHPT is difficult without further questioning and quality of life assessments (eg SF-36® health survey and Symptom Checklist–90). Such details usually remain absent without specialist referral and multidisciplinary team review. A study by Hasse et al showed that the incidence of truly asymptomatic PHPT is as low as 9.3% and concluded that ‘asymptomatic’ patients may benefit, both objectively and subjectively, from parathyroidectomy similarly to symptomatic patients.13 This viewpoint is supported by randomised control trials and long-term prospective studies that show improvements in quality of life, bone mineral density, functional capacity and cognitive function.14-17

Vague symptoms, similar to those of hyperparathyroidism, are often seen in the elderly population. Hence, it is important to distinguish those attributable to PHPT with corresponding biochemical abnormalities. Such patients may be cured of their symptoms with parathyroidectomy and age alone should not act as a contraindication to surgery.18,19 In some circumstances potentially curable co-morbidities act as barriers to specialist referral and surgery. The role of parathyroidectomy in reversing hyperparathyroidism-related cardiovascular disease remains debatable. However, a study by Stefanelli et al showed reduced progression of valvular calcification and regression of hypertrophy.4 In light of advanced imaging and minimally invasive techniques, surgery should be considered for such patients.

There exists a narrow window of opportunity to assess this cohort prior to a deterioration in the patients' condition that may prevent them from benefiting from surgery in the future. Multidisciplinary teams are therefore essential in identifying those patients most likely to benefit from surgery and, importantly, to accurately distinguish adenomas from hyperplasia.

Conclusions

PHPT remains a poorly managed yet curable disease. All patients with biochemically proven hyperparathyroidism should be referred for specialist assessment by a multidisciplinary team. Specialist referral provides an opportunity for detailed symptomatic and quality of life assessment, leading to appropriate decisions on surgical intervention, medical treatment and follow-up. In order to offer such a service, better education and guidance for GPs and hospital physicians alike is required.

Acknowledgments

The material in this article was presented as a poster at the British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons annual meeting held in London, UK, November 2009.

References

- 1.Mundy GR, Cove DH, Fisken R. Primary hyperparathyroidism: changes in the clinical presentation. Lancet. 1980;1:1,317–1,320. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gittoes NJ, Cooper MS. Primary hyperparathyroidism – is mild disease worth treating? Clin Med. 2010;10:45–49. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.10-1-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP, Bone HG, et al. Therapeutic controversies in primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2,275–2,285. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.7.5842-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefenelli T, Mayr H, Bergler-Klein J, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism: incidence of cardiac abnormalities and partial reversibility after successful parathyroidectomy. Am J Med. 1993;95:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90260-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farr HW, Fahey TJ Jr, Nash AG, Farr CM. Primary hyperparathyroidism and cancer. Am J Surg. 1973;126:539–543. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(73)80046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wajngot A, Werner S, Granberg PO, Lindvall N. Occurrence of pituitary adenomas and other neoplastic diseases in primary hyperparathyroidism. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;151:401–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Utiger RD. Treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1,301–1,302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ready AR, Sabharawal T, Barnes AD. Parathyroidectomy in the West Midlands. Br J Surg. 1996;83:823–827. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.British Association of Endocrine Surgeons. Guidelines for the Surgical Management of Endocrine Disease and Training Requirements for Endocrine Surgery. London: BAES; 2003. pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilezikian JP, Khan AA, Potts JT Jr. Guidelines for the management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: summary statement from the third international workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:335–339. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udelsman R. Six hundred fifty-six consecutive explorations for primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Surg. 2002;235:665–670. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Udelsman R, Pasieka JL, Sturgeon C, et al. Surgery for asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: proceedings of the third international workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:366–372. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasse C, Sitter H, Bachmann S, et al. How asymptomatic is asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism? Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2000;108:265–274. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambrogini E, Cetani F, Cianferotti L, et al. Surgery or surveillance for mild asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3,114–3,121. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris GS, Grubbs EG, Hearon CM, et al. Parathyroidectomy improves functional capacity in ‘asymptomatic’ older patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: a randomized control trial. Ann Surg. 2010;251:832–837. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d76bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasieka JL, Parsons L, Jones J. The long-term benefit of parathyroidectomy in primary hyperparathyroidism: a 10-year prospective surgical outcome study. Surgery. 2009;146:1,006–1,013. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrier ND, Balachandran D, Wefel JS, et al. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of parathyroidectomy versus observation in patients with ‘asymptomatic’ primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 2009;146:1,116–1,122. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kebebew E, Duh QY, Clark OH. Parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism in octogenarians and nonagenarians: a plea for early surgical referral. Arch Surg. 2003;138:867–871. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.8.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roche NA, Young AE. Role of surgery in mild primary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1,640–1,649. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NIH conference. Diagnosis and management of asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: consensus development conference statement. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:593–597. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-7-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]