Abstract

INTRODUCTION

In the North Trent Cancer Network (NTCN) patients requiring retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for metastatic testicular cancer have been treated by vascular service since 1990. This paper reviews our experience and considers the case for involvement of vascular surgeons in the management of these tumours.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients referred by the NTCN to the vascular service for retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy between 1990 and 2009 were identified through a germ cell database. Data were supplemented by a review of case notes to record histology, intraoperative and postoperative details.

RESULTS

A total of 64 patients were referred to the vascular service for retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, with a median age of 29 years (16–63 years) and a median follow-up of 4.9 years. Ten patients died: eight from tumour recurrence, one from septicaemia during chemotherapy and one by suicide. Of the 54 who survived, 7 were alive with residual masses and 47 patients were disease-free at the last follow-up. Sixteen patients required vascular procedures: four had aortic repair (fascia), three had aortic replacement (spiral graft), four had inferior vena cava resection, two had iliac artery replacement and two had iliac vein resection.

CONCLUSIONS

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection often involves mobilisation and/or the resection/replacement of major vessels. We recommend that a vascular surgeon should be a part of testicular germ cell multidisciplinary team.

Keywords: Testicular cancer, Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, Post-chemotherapy, Germ cell tumours

Testicular germ cell tumours are the most common malignancies in men aged 15–40 years.1 There has been an increased incidence over the past few decades in the UK,2,3 US4 and other Caucasian populations.5 Although the aetiology is unknown, developmental urogenital abnormalities,6 undescended testes and inguinal hernias have all been associated with higher rates,7 with sedentary lifestyle, early puberty and genetics also implicated as risk factors.8-10

The British Testicular Tumour Panel and Registry classifies malignant testicular germ cell tumours into two main histological groups: seminomas and teratomas.11 Para-aortic lymph nodes are the most common sites of metastatic disease.

Along with the tumour pathology and clinical stage, preoperative staging investigations inform the choice of further treatment, which may be surveillance, chemotherapy or radiotherapy.12 Chemotherapy is usually recommended for those with evidence of metastatic disease while surgical resection is considered for patients with significant residual masses, particularly in the para-aortic region.

Surgery is most likely to play a role in improving the outcome of treatment by resecting residual masses in intermediate and poor prognosis patients who are in remission following chemotherapy.

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) is the most common form of surgery required13 and national guidance recommends that the treatment of patients with advanced disease or recurrence should be carried out in specialised centres.14 In the North Trent Cancer Network (NTCN), vascular surgeons have been members of the germ cell multidisciplinary team and patients requiring RPLND for metastatic testicular cancer have been treated by the vascular service since 1990. This paper reviews our experience and considers the case for involvement of vascular surgeons in the management of these tumours.

Methods

All patients diagnosed with testicular germ cell tumour in the NTCN between 1990 and 2009 were entered into a germ cell database. Patients referred to the vascular service for RPLND were identified through this database. The main indications for surgical referral were a residual para-aortic mass of >1–2cm after chemotherapy or as part of the treatment of relapsed disease, particularly an enlarging para-aortic mass.

The demographical data and chemotherapy treatment details were routinely recorded on the germ cell database. Data were supplemented by a retrospective review of the case notes of the patients who underwent surgery to record intraoperative details, postoperative complications and histology of the resected tumour.

Surgical technique

An anaesthetist experienced with the procedure should ideally be available as many of the patients receive bleomycin as part of chemotherapy regimens. There is evidence that bleomycin can damage the lungs15 and so the use of a low inspired oxygen concentration is advised to avoid pneumonitis.

Surgical access is usually via a curved transverse upper abdominal incision. This may be extended laterally to facilitate nephrectomy, if required, and can be covered by a thoracic epidural for postoperative pain relief. The most common site for metastatic tumour is the left side of the aorta, just below the left renal vein, usually involving the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery.

Not uncommonly, the tumour extends behind or around the aorta and inferior vena cava (IVC), laterally into the renal pelvis and posteriorly into the psoas muscle.

The inferior mesenteric artery is usually ligated and divided flush with the aorta and we have never had a problem with colonic ischaemia in these young patients. Retrograde ejaculation, however, is common due to damage to the postganglionic sympathetic fibres and patients must be made aware of this.

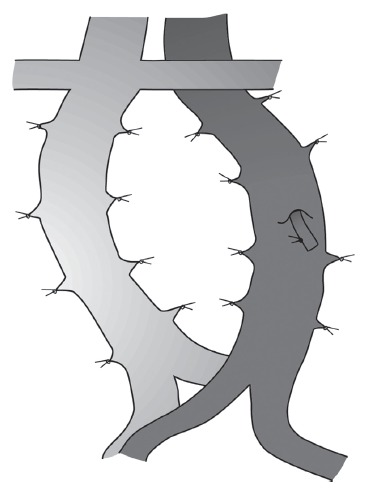

The aorta can be mobilised to improve access to tumours between or behind the aorta or IVC by ligating and dividing the lumbar arteries. The lumbar veins can be ligated and divided in the same way to mobilise the infrarenal IVC (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

The lumbar arteries and lumbar veins can be ligated and divided to increase the mobility of the infrarenal aorta and inferior vena cava, thereby facilitating the dissection of posterior tumours.

The amount of mobilisation of the great vessels that can be achieved by this manoeuvre is surprising and we have not encountered any problem with spinal ischaemia. The tumour can usually be excised from the great vessels by sharp dissection in the adventitial plane. Occasionally, the vena cava and/or aorta may need to be resected en bloc because of tumour involvement and this may contribute to a prolonged tumour-free interval.16,17

A small defect in the aorta can be repaired with a piece of the abdominal wall fascia.

Although rifampicin-soaked polyethylene terephthalate can be used for aortic reconstruction, the use of prosthetic material to replace the aorta is best avoided to prevent the risk of infection in these immunocompromised young patients.

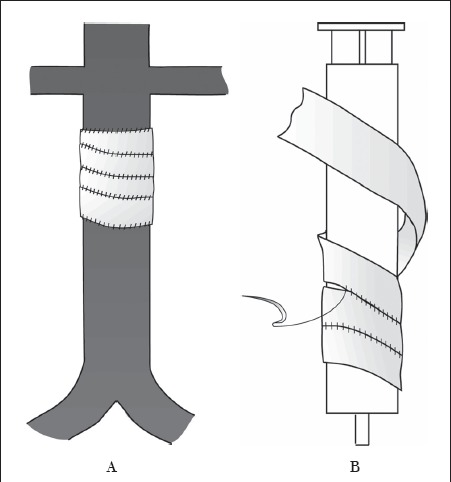

The aorta can be reconstructed using a spiral vein graft. The long saphenous vein is harvested, opened longitudinally and sutured in a spiral fashion around a syringe of the same diameter as the aorta (Fig 2). This procedure can take some time and one patient required fasciotomies for subsequent compartment syndrome. Bovine or equine pericardium and superficial femoral vein can be used for aortic reconstruction but it is the authors' preference to use long saphenous vein spiral graft.

Figure 2.

The long saphenous vein is opened longitudinally and sutured in a spiral fashion over a syringe of the same diameter as the aorta to form a tube A that can then be used to replace the infrarenal aorta B.

Resection of the IVC causes some postoperative leg swelling although this can be controlled with compression hosiery.

To prevent the formation of chylous ascites, lymphatics are ligated with either sutures or clips. The ureter can usually be dissected off the tumour mass but involvement of the renal pelvis normally requires nephrectomy. Posterior invasion into the psoas requires partial resection of the muscle, then oversewing of the lumbar arteries and veins once the tumour mass has been removed. Cell salvage was used routinely in all cases.

Results

A total of 861 patients in the NTCN were diagnosed with a germ cell tumour between 1990 and 2009. Of these, 64 patients were referred to the vascular service for RPLND with their age at diagnosis ranging from 16 to 63 years (mean 29 years, median 29 years). The original tumour was teratomatous in 62 cases, seminomatous in one case and one patient had a metastatic melanoma. The cancer originated in the testes of 63 patients while one germ cell tumour was extragonadal.

All tumours were staged at the time of diagnosis using the Royal Marsden classification.11 The histological data from ten cases (16%) were unavailable on retrospective analysis. Of the fifty-four patients with histological data available, eight were in stage 1, twenty in stage 2, five in stage 3 and twenty-one in stage 4. The number of deaths and survivors from each of the four stages of the Marsden classification are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient deaths and survival according to the Royal Marsden classification stage

| Marsden stage | Number of patient deaths during review period (% of total) | Number of patients surviving up to review period (% of total) | Total number (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 (0) | 8 (15) | 8 (15) |

| 2 | 4 (7) | 16 (30) | 20 (37) |

| 3 | 1 (2) | 4 (7) | 5 (9) |

| 4 | 4 (7) | 17 (31) | 21 (39) |

Histology of the resected specimens showed a viable tumour in 42 (78%) cases. Necrosis/fibrosis only was demonstrated in 12 (22%) cases. Perioperative blood loss was up to 10,500ml (mean 934ml). Nineteen (30%) patients suffered one or more postoperative complications (Table 2). One patient, a Jehovah's Witness, died in the early postoperative period following haemorrhage from the renal bed despite the use of cell salvage.

Table 2.

Postoperative complications

| Complication | Total (% of total) |

|---|---|

| Postoperative bleeding* | 2 (3) |

| Retrograde ejaculation* | 2 (3) |

| Chest infection | 12 (19) |

| Pancreatitis* | 1 (2) |

| Prolonged ileus | 6 (9) |

| Chyloperitoneum* | 2 (3) |

| Pulmonary embolus* | 1 (2) |

| Wound infection | 2 (3) |

| Compartment syndrome* | 1 (2) |

| Acute tubular necrosis* | 1 (2) |

| Adhesional bowel obstruction* | 1 (2) |

Additional operative procedures along with RPLND were performed in 32 (50%) patients. Of these, fifteen patients required vascular procedures: four had aortic repair (fascia), three had aortic replacement (spiral graft), four had IVC resection, two had iliac artery replacement and two had iliac vein resection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of additional intraoperative procedures

| Procedure | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Aortic repair (fascia) | 4 (6) |

| Aortic replacement (spiral graft) | 3 (5) |

| Inferior vena cava resection | 4 (6) |

| Iliac artery replacement | 2 (3) |

| Iliac vein resection | 2 (3) |

| Nephrectomy | 7 (11) |

| Ureter divided and repaired (over stent) | 10 (16) |

The length of follow-up up to the period of the review ranged from 3 months to 12 years, with a mean of 4 years 10 months and a median of 4 years 11 months. During the review period, ten (15.6%) patients died: eight from tumour recurrence, one from septicaemia during chemotherapy and one committed suicide. Of the 54 that survived, 7 were alive with residual retroperitoneal masses and the remaining 47 patients were disease-free at their last follow up.

Objective assessment of patency rates following arterial and venous reconstructions were not carried out in this study. However, none of the patients have presented with any signs of significant arterial or venous occlusion during the follow-up period.

Discussion

Survival following testicular tumours have continued to improve in the last decade so that cure rates of up to 95% are possible.14,16

Patients with metastatic disease can be divided into good, intermediate and poor prognostic categories16,18 on the basis of stage and tumour markers with five-year survival rates of >90%, 80–85% and 50–60% respectively.18,19 The role of open RPLND in the management of testicular cancer is now established,20 with laparoscopic RPLND also being performed for smaller masses.16,18,20,21

Up to 50% of patients with a radiological stage 1 tumour and histological evidence of vascular invasion may have retroperitoneal lymph node involvement.13 Primary RPLND is an established treatment in some centres in the US. However, UK practice is geared toward adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy and surveillance for the group of patients without vascular invasion, with a 20% risk of recurrence.22

In stage 2 disease, studies have clearly shown a benefit with RPLND and it has long been established that stage 2 disease can be cured by adjuvant RPLND.20,22

A multicentre study of 239 patients undergoing RPLND revealed a postoperative complication rate of 20% and a mortality rate of 2%.23

The most common complications reported were wound infection and prolonged ileus, and major complications included chylous ascites, pulmonary embolism, small bowel obstruction and pancreatitis.

The overall complication rate reported in literature varies between 20% and 35%.24 Late recurrence (after two years) occurs in 2–5% of patients treated for testicular cancer and the prognosis in these patients is poor.25,26 We have compared our results with previous studies (Table 4) and our major complication rate of 19% and mortality rate of 1.6% is comparable with these studies.23,24,27-29

Table 4.

Comparison of results of post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection

| Study | Number of patients | Study period | Mean follow up (months) | Complications | Vascular procedures | Mortality | 5-year survival rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baniel et al24 | 603 | 1982–1992 | 20.7% | 0.8% | |||

| Eggener et al27 | 71 | 1989–2004 | 52 | 74% | |||

| Hartmann et al28 | 134 | 1978–1995 | 60 | 1% | 66% | ||

| Heidenrich et al23* | 239 | 1995–2000 | 19.6% | 2% | 94% | ||

| Hendry et al29 | 442 | 1976–1999 | 76.8 | 4.5% | 8.3% | 1.8% | 83% |

| Our study | 64 | 1990–2009 | 59 | 19%** | 25% | 1.6% | 73.4% |

primary nerve sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection

only major complications included

Laparoscopic RPLND has been described in the treatment of patients with testicular tumours.21,30,31 Primary laparoscopic RPLND for low stage testicular tumours has shown to have reduced morbidity compared with the open technique.21,30-32 However, post-chemotherapy laparoscopic RPLND is a technically challenging procedure with high complication and conversion rates.33,34 Nevertheless, there is a role for the laparoscopic approach to RPLND in properly selected patients and with an appropriately skilled surgeon.

IVC resection was carried out in four (6%) patients in our study. Although IVC reconstruction has been described, it is a complex, time consuming procedure. On the other hand, IVC resection in young patients is relatively well tolerated and rarely results in any major complications35 and hence we elected to perform IVC resection when necessary.

Advances in chemotherapy, radiological staging and a multidisciplinary team approach have dramatically improved the prognosis for patients with testicular tumours. Imaging modalities like positron emission tomography have improved the detection of active tumour, thereby avoiding false negative resections.

In most centres RPLND is performed by urologists as lead surgeons. Vascular injuries are the most common serious complications during RPLND.33,36

Christmas et al reported 98 patients undergoing post-chemotherapy RPLND and all of these patients required vascular intervention.36 In the present study, 16 (20%) patients required major vascular intervention along with RPLND. In the authors' opinion vascular surgeons have a useful role to play as a part of the multidisciplinary team involved in RPLND. Good results following RPLND can be obtained with a multidisciplinary team including urologists, transplant surgeons, hepatobiliary surgeons and vascular surgeons.

Conclusions

Complete tumour clearance can usually be achieved but often involves mobilisation and/or resection and replacement of major vessels, requiring the involvement of a vascular surgeon. We therefore recommend that the multidisciplinary team treating testicular germ cell tumours includes a vascular surgeon.

References

- 1.Manecksha RP, Fitzpatrick JM. Epidemiology of testicular cancer. BJU Int. 2009;104(9 Pt B):1,329–1,333. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle P, Kaye SB, Robertson AG. Changes in testicular cancer in Scotland. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:827–830. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(87)90286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll R. Are we winning the war against cancer? A review in memory of Keith Durrant. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1992;4:257–266. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)81065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown LM, Pottern LM, Hoover RN, et al. Testicular cancer in the United States: trends in incidence and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 1986;15:164–170. doi: 10.1093/ije/15.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone JM, Cruickshank DG, Sandeman TF, Matthews JP. Trebling of the incidence of testicular cancer in Victoria, Australia (1950–1985) Cancer. 1991;68:211–219. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910701)68:1<211::aid-cncr2820680139>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aetiology of testicular cancer: association with congenital abnormalities, age at puberty, infertility, and exercise. United Kingdom Testicular Cancer Study Group. BMJ. 1994;308:1,393–1,399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman D. Epidemiology of testis cancer. In: Oliver RTD, Blandy JP, Hope-Stone HF, editors. Urological and Genital Cancer. Oxford: Blackwell; 1989. pp. 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynge E, Knudsen LB, Møller H. Vasectomy and testicular cancer: epidemiological evidence of association. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:1,064–1,066. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss AR, Osmond D, Bacchetti P, et al. Hormonal risk factors in testicular cancer. A case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:39–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapley EA, Crockford GP, Teare D, et al. Localization to Xq27 of a susceptibility gene for testicular germ-cell tumours. Nat Genet. 2000;24:197–200. doi: 10.1038/72877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pugh RCB. Pathology of the Testis. Oxford: Blackwell; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of Adult Testicular Germ Cell Tumours. Edinburgh: SIGN; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donohue JP, Thornhill JA, Foster RS, et al. Primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in clinical stage A non-seminomatous germ cell testis cancer. Review of the Indiana University experience 1965–1989. Br J Urol. 1993;71:326–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb15952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dearnaley D, Huddart R, Horwich A. Regular review: Managing testicular cancer. BMJ. 2001;322:1,583–1,588. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldiner PL, Schweizer O. The hazards of anesthesia and surgery in bleomycin-treated patients. Semin Oncol. 1979;6:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maldonado-Valadez R, Schilling D, Anastasiadis AG, et al. Post-chemotherapy laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection in testis cancer patients. J Endourol. 2007;21:1,501–1,504. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spitz A, Wilson TG, Kawachi MH, et al. Vena caval resection for bulky metastatic germ cell tumors: an 18-year experience. J Urol. 1997;158:1,813–1,818. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:594–603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones RH, Vasey PA. Part II: testicular cancer – management of advanced disease. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:738–747. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldenburg J, Alfsen GC, Lien HH, et al. Postchemotherapy retroperitoneal surgery remains necessary in patients with nonseminomatous testicular cancer and minimal residual tumor masses. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3,310–3,317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neyer M, Peschel R, Akkad T, et al. Long-term results of laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ-cell testicular cancer. J Endourol. 2007;21:180–183. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Constantinidou A, Aravantinos G. Current management of stage I testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumours. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heidenreich A, Albers P, Hartmann M, et al. Complications of primary nerve sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: experience of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. J Urol. 2003;169:1,710–1,714. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000060960.18092.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baniel J, Sella A. Complications of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in testicular cancer: primary and post-chemotherapy. Semin Surg Oncol. 1999;17:263–267. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199912)17:4<263::aid-ssu7>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baniel J, Foster RS, Einhorn LH, Donohue JP. Late relapse of clinical stage I testicular cancer. J Urol. 1995;154:1,370–1,372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerl A, Clemm C, Schmeller N, et al. Late relapse of germ cell tumors after cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:41–47. doi: 10.1023/a:1008253323854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggener SE, Carver BS, Loeb S, et al. Pathologic findings and clinical outcome of patients undergoing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection after multiple chemotherapy regimens for metastatic testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2007;109:528–535. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann JT, Schmoll HJ, Kuczyk MA, et al. Postchemotherapy resections of residual masses from metastatic non-seminomatous testicular germ cell tumors. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:531–538. doi: 10.1023/a:1008200425854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hendry WF, Norman AR, Dearnaley DP, et al. Metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: results of elective and salvage surgery for patients with residual retroperitoneal masses. Cancer. 2002;94:1,668–1,676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhayani SB, Allaf ME, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic RPLND for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer: current status. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton RJ, Finelli A. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors: current status. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albqami N, Janetschek G. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection in the management of clinical stage I and II testicular cancer. J Endourol. 2005;19:683–692. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Permpongkosol S, Lima GC, Warlick CA, et al. Postchemotherapy laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: evaluation of complications. Urology. 2007;69:361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palese MA, Su LM, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection after chemotherapy. Urology. 2002;60:130–134. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01670-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck SD, Lalka SG. Long-term results after inferior vena caval resection during retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for metastatic germ cell cancer. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:808–814. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christmas TJ, Smith GL, Kooner R. Vascular interventions during post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection for metastatic testis cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1998;24:292–297. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(98)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]