Abstract

Background

By increasing the intracellular prooxidant burden, gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) may accelerate atherosclerotic vascular disease. That noxious influence may be reflected by circulating enzyme levels, a correlate of cardiovascular risk factors, and a predictor of incident events. To evaluate this hypothesis, we tested the association between circulating GGT and common carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), a surrogate index of systemic atherosclerotic involvement, in a large and well-characterized group of patients at risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Patients

This study analyzed 548 patients with hypertension and/or diabetes and a widely prevalent history of CVD. Subjects with known hepatic disease and abnormal GGT values were excluded.

Methods

CIMT (B-mode ultrasonography) values were the mean of four far-wall measurements at both common carotids. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was diagnosed according to National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III criteria. Due to inherent sex-related differences in GGT levels, the data were analyzed separately in males and females in samples dichotomized by the median.

Results

The age-adjusted CIMT values did not differ by GGT levels in males or females. In contrast, the carotid wall was consistently thicker in patients with a history of CVD and MetS independent of age and concurrent GGT values. In both sexes, GGT was associated with key components of the MetS such as triglycerides, fasting plasma glucose, and body mass index.

Conclusion

The data collected in this mixed group of hypertensive and/or diabetic patients with widely prevalent history of CVD do not support the concept of a direct pathophysiological link between GGT levels within reference limits and atherosclerotic involvement.

Keywords: gamma-glutamyltransferase, carotid intima-media thickness, atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome

Introduction

Consistent evidence associates increased circulating serum gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), a parameter conventionally used for diagnosing hepatobiliary diseases and alcohol abuse,1 with incident cardiovascular disease (CVD)2 and major proatherogenic risk factors.3 For this reason, GGT determination has been added to the array of biomarkers useful for stratifying cardiometabolic risk.4 Furthermore, the enzyme’s active involvement in the atherogenic process was hypothesized on the basis of its potential to increase the intracellular prooxidant burden through the iron-reducing properties of cysteinylglycine moieties generated during GGT-catalyzed glutathione hydrolysis.5 The identification of prooxidant GGT activity in atheromatous plaques of carotid and coronary arteries6 adds to the need for further clinical evaluation.

Since the first demonstration of its close correlation with directly measured arterial wall thickness, carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) determination7 has become an easily obtained and noninvasive standard surrogate measure of systemic atherosclerosis and a prognostic and therapeutic end-point in epidemiological and pharmacological trials.8 Therefore, ultrasound-derived CIMT offers a way to assess the relationship between GGT levels and atherosclerotic vascular disease. This rarely addressed issue was evaluated in this retrospective cross-sectional analysis of a large and well-characterized sample of patients screened at our institution.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study examined 548 consecutive Caucasian subjects who were referred to our department between January 2006 and June 2010 for hypertension and/or diabetes. Table 1 provides clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample. Subjects with history of liver disease, self-reported alcohol abuse, history of hepatitis B or C, anticonvulsants, and microsomal enzyme-inducing drugs active on hepatic GGT release1 were excluded. Only patients with GGT levels within the reference values of our laboratory (<60 e 40 U/L for males and females, respectively) were included in the analysis. Statin and antihypertensive (mostly angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers) treatment at the time of the visit was retrieved from the records. Table 1 presents the relative percentages.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics by sex

| Variables | Females n = 217 |

Males n = 331 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIMT (mm) | 0.80 ± 0.19 | 0.86 ± 0.20 | <0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 15 (9) | 27 (20) | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 17 (7) | 22 (13) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 93 (57) | 118 (77) | <0.001 |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 90 (16) | 95 (18) | <0.001 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 4.7 | 26.8 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 10% | 22% | <0.001 |

| Active smokers | 12% | 25% | <0.001 |

| History of CVD | 19% | 40% | <0.001 |

| Statins | 54% | 67% | <0.01 |

| Antihypertensive Rx | 51% | 70% | <0.001 |

| Total-CHOL (mg/dL) | 216 ± 38 | 195 ± 38 | <0.001 |

| LDL-CHOL (mg/dL) | 140 ± 36 | 131 ± 37 | <0.01 |

| HDL-CHOL (mg/dL) | 67 ± 15 | 52 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 59 ± 14 | 60 ± 13 | NS |

| SBP (mmHg) | 133 ± 18 | 133 ± 16 | NS |

| Hypertension | 75% | 80% | NS |

Note: Means ± SD, medians (interquartile range) and percentages.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transferase; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; HDL-CHOL, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-CHOL, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; NS, nonsignificant; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Carotid-scanning protocol

The patients were screened while in supine position with the head and neck gently rotated 45 degrees from the side where the scanning was performed. The examination started by visualizing the longitudinal image of the midportion of the common carotid arteries in the supraclavicular region by moving and rotating the transducer until the sonographer demonstrated and marked the bifurcation with the cursor. Next, the sonographer focused on the interfaces required for the measurements of the arterial wall thickness of the common carotid artery (CCA) segment within 40 mm proximal to the carotid bulb. Patients with arteries in which the references were unidentifiable, tortuous, or calcified were excluded. All measurements were made with the image at the maximum depth of focus. The operator set up the gains and image pre- and post-processing options for every patient and for each artery to obtain the best possible image. Measurements of the distance from the leading edge of the first echogenic luminal, bright line to the leading edge of the second echogenic line were taken manually from frozen images as indicated by Pignoli7 in order to express the distances in mm. Scanning and measurements were obtained by a Philips ie33® instrument (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) equipped with a linear 7.5 MHz probe (axial resolution: 0.1 mm) and by the same observer (MN, within-observer variability: 5.3%, the average variation coefficient of 20 triplicate measurements in control subjects).

Biochemistry

GGT was measured colorimetrically by the nitroanilide method on a Cobas Mira Plus (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) chemistry instrument. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol (CHOL), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-CHOL), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-CHOL), and triglycerides were assessed by automated standard enzymatic and colorimetric methods. All the samples were processed in the same laboratory, and quality control was ensured by the regional branch of the National Health System (Regione Toscana, Controllo di Qualità in Medicina di Laboratorio9).

The systolic (S) and diastolic (phase V Korotkoff) blood pressure (BP) values refer to sphygmomanometric measurements taken in sitting position at the time of CIMT determination. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg on a scale with an attached height measurement device.

Definitions

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) includes coronary heart disease (previous myocardial infarction, unstable and stable angina, coronary artery bypass graft, or angioplasty), peripheral arterial disease (previous lower limb surgery, angioplasty, or current claudication confirmed by echo-Doppler studies, angiograms, or others), and carotid disease (previous endarterectomy or carotid stenosis >50% at echo-Doppler imaging) (Table 2). Diabetes and hypertension were either diagnosed based on ongoing treatment or by the presence of fasting plasma glucose >125 mg/dL and BP >130/85 respectively. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was defined according to National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) criteria10 in the presence of at least three of the following criteria: antihypertensive treatment or BP >130/85 mmHg, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL, HDL-C <40 mg/dL in males and <50 mg/dL in females, glucose-lowering treatment, or FPG >110 mg/dL, abdominal obesity. The thresholds for abdominal obesity were BMI ≥29.5 kg/m2 and ≥27.2 kg/m2 in men and women, respectively since those values corresponded to 102 cm and 88 cm of waist circumference in men and women, respectively, in a regression of BMI on the waist as validated previously.11 Smokers were either categorized as current smokers independent of the number of cigarettes they had per day or as never/previous smokers, meaning tobacco-free for at least 6 months.

Table 2.

Distribution (absolute numbers and percentages) by type of vascular disease (n = 174) in descending order of frequency

| Type of vascular disease | n = 174 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Multivessel disease | 71 | 40 |

| Coronary heart disease | 50 | 29 |

| Carotid artery disease | 43 | 25 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 10 | 6 |

Note: Multivessel disease indicates the coexistence in the same patient of two or more of the listed vascular diseases.

Data processing

The data were analyzed by sex-specific median GGT values (cutoffs: 15 U/L and 27 U/L for females and males, respectively). CIMT was the average of the four values measured bilaterally approximately 1 cm from the other at the far wall of the CCA, provided that these points were free of plaque. Plaques (a local thickening exceeding 1.4 mm and protruding into the lumen) were excluded from the measurements. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (Kg/m2). For the sake of clarity, only the SBP values were reported since diastolic BP did not vary across comparisons.

Statistics

Differences in continuous and categorical variables were assessed by one-way analysis of variance and chi-square statistics, respectively, and were adjusted for age by analysis of covariance and logistic regression. Unless otherwise specified, descriptive statistics were mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for skewed data and percentages for categorical variables. The limit for statistical significance was P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics by gender

CIMT, GGT ALT, triglycerides, FPG, BMI were higher and diabetes, active smoking, history of CVD, and pharmacological treatment more frequent in males than females whereas total and fractionated CHOL showed opposite trends. Age, SBP, and history of hypertension did not differ by gender (Table 1).

Clinical and demographic characteristics by GGT status in males and females

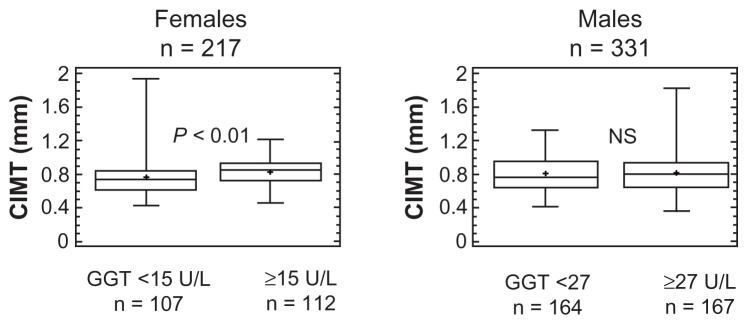

In contrast to the homogeneous distribution of such parameters in men, thicker carotid walls (Figure 1), higher SBP, and more frequent hypertension and statin treatment distinguished women with above from those below median GGT levels (Table 3). However, differences in CIMT (Age-corrected means [95% confidence interval (CI)]: 0.80 [0.77–0.83] versus 0.79 [0.76–0.81] mm) and in other parameters (data not shown) were abolished by accounting for the older age of the female subgroup (Table 3). In both sexes, above-median GGT levels were associated with higher ALT, triglycerides, FPG, and BMI (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Box-and-whisker plots of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) by above- and below-median gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) levels in females (left panel) and males (right panel).

Notes: The statistical difference in women was abolished when age difference was taken into account. The central box encloses the middle 50% of the data; the horizontal line inside the box represents the median, and the mean is plotted as a cross. Vertical lines (whiskers) extend from each end of the box and cover four interquartile ranges.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics by above- and below-median sex-specific GGT levels

| Variables | Females n = 217 |

Males n = 331 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| <15 U/L n = 107 |

≥15 U/L n = 112 |

P-level | 27 U/L n = 164 |

≥27 U/L n = 167 |

P-level | |

| GGT (U/L) | 11 (3) | 20 (8) | – | 19 (9) | 39 (14) | – |

| Age (years) | 55 ± 14 | 64 ± 12 | <0.001 | 61 ± 15 | 59 ± 12 | NS |

| SBP (mmHg) | 128 ± 18 | 138 ± 17 | <0.001 | 132 ± 15 | 135 ± 15 | NS |

| Hypertension | 64% | 87% | <0.001 | 79% | 87% | NS |

| Statins | 40% | 68% | <0.001 | 63% | 71% | NS |

| Antihypertensive Rx | 40% | 63% | <0.01 | 65% | 74% | NS |

| ALT (U/L) | 15 (6) | 18 (7) | <0.001 | 19 (9) | 25 (15) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 81 (42) | 108 (67) | <0.001 | 102 (71) | 126 (74) | <0.01 |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 86 (13) | 95 (16) | <0.001 | 94 (17) | 97 (21) | <0.01 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 24.8 ± 4.5 | 26.3 ± 4.4 | <0.05 | 26.0 ± 2.9 | 27.5 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Total-CHOL (mg/dL) | 209 ± 38 | 223 ± 37 | <0.01 | 190 ± 39 | 200 ± 35 | <0.05 |

| LDL-CHOL (mg/dL) | 133 ± 38 | 146 ± 35 | <0.01 | 127 ± 37 | 136 ± 35 | <0.05 |

| HDL-CHOL (mg/dL) | 68 ± 15 | 66 ± 15 | NS | 54 ± 15 | 51 ± 13 | NS |

| Active smokers | 12% | 12% | NS | 22% | 25% | NS |

| History of CVD | 16% | 22% | NS | 41% | 39% | NS |

| Diabetes | 7% | 13% | NS | 19% | 25% | NS |

Note: Means ± SD, medians (interquartile range) and percentages.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transferase; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; HDL-CHOL, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-CHOL, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; NS, nonsignificant; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

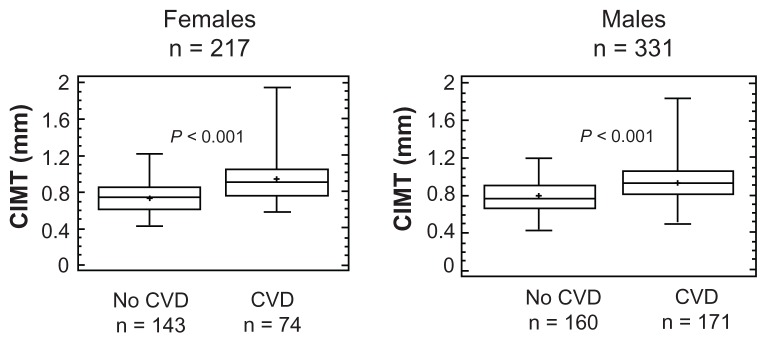

The flat behavior of CIMT by GGT levels diverged quite sharply from the carotid thickening shown by patients with a history of CVD as compared with those without, a statistically significant (P < 0.001) pattern unaffected by the adjustment for age (Figure 2). Circulating GGT levels were comparable in patients with a history of CVD and not, either females (17 [9] versus 14 [8] U/L, n = 41 versus 176 respectively, NS) or males (26 [20] versus 28 [19] U/L, n = 133 versus 198 respectively, NS).

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plots of CIMT by history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in females (left panel) and males (right panel).

Notes: The central box encloses the middle 50% of the data; the horizontal line inside the box represents the median, and the mean is plotted as a cross. Vertical lines (whiskers) extend from each end of the box and cover four interquartile ranges.

Clinical and demographic characteristics by MetS status

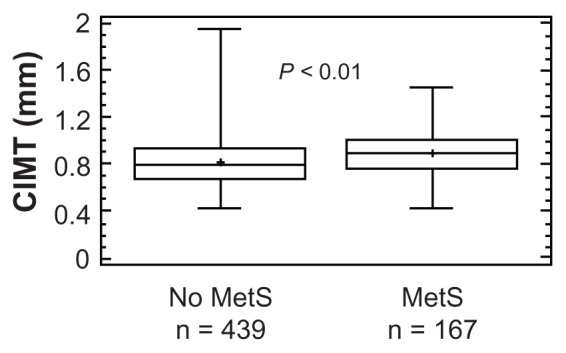

Besides the expected liver enzyme elevations4 and definition-related10 modifications of the metabolic and pressor profile (Table 4), CIMT was higher in patients with MetS (Figure 3) and was unchanged after adjusting for GGT levels (GGT-corrected means [95% CI]: 0.82 [0.80–0.84] versus 0.88 [0.86–0.92] mm, P < 0.01).

Table 4.

Demographic and clinical characteristics by MetS status

| Variables | No MetS n = 439 |

MetS n = 109 |

P-level |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGT (U/L) | 19 (16) | 27 (15 | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 19 (9) | 24 (18) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 96 (51) | 186 (68) | <0.001 |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 94 (15) | 115 (29) | <0.001 |

| HDL-CHOL (mg/dL) | 61 ± 15 | 45 ± 15 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 ± 3.6 | 29.6 ± 4.1 | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 132 ± 17 | 139 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 10% | 46% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 65% | 90% | <0.001 |

| M/F | 42%/58% | 32%/68% | NS |

| Age (years) | 60 ± 14 | 61 ± 12 | NS |

Note: Means ± SD, medians (interquartile range) and percentage.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transferase; BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; HDL-CHOL, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NS, nonsignificant; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Box-and-whisker plot of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) by National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III defined metabolic syndrome (MetS) status.10

Notes: The central box encloses the middle 50% of the data; the horizontal line inside the box represents the median, and the mean is plotted as a cross. Vertical lines (whiskers) extend from each end of the box and cover four interquartile ranges.

Discussion

The lack of relationship between GGT and CIMT

Our cross-sectional evaluation of a large and rather heterogeneous group of hypertensive and/or diabetic patients widely affected by CVD shows a lack of association between circulating GGT levels and CIMT, a surrogate measure of systemic atherosclerosis.8 This negative result was immediately evident in men and emerged quite clearly in women after accounting for the older age of those with higher GGT. That demographic influence was consistent with previous reports1 of trends toward declining values in elderly males whose large representation in our sample may explain why age and GGT showed a different association profile between sexes. One might also ask whether the effect of statins on liver enzymes12 might have contributed to the divergent pattern, but this is unlikely since statin treatment did not differ by GGT levels in males, and was appropriately more frequent in older females with higher GGT levels. The strength of these findings is augmented when contrasted with the carotid thickening that characterized patients with a history of CVD, a reassuring piece of evidence in agreement with the concept of carotid imaging as an indicator of the atherosclerotic burden across different vascular beds.8

Our results are inconsistent with the active contribution of GGT in the initiation and progression of atherosclerotic vascular disease, at least to the extent reflected by carotid imaging. This issue has been addressed by a few studies biased by low statistical strength of the reported correlations, limited sample size, unbalanced male-to-female ratios and, most importantly, missing adjustment for sex and age.13–15 This latter limitation is of particular relevance when considering the confounding effect of demographic variables on CIMT in our study. This is in agreement with Volzke et al’s study on a large sample of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)16 in which anatomic alterations ranging from mere liver steatosis to steatohepatitis coexisted with elevated GGT and related metabolic abnormalities.17,18 Our conclusions are further supported by negative results reported in several series of patients with NAFLD,19–22 a condition that affected also an undefined but large portion of our patients, particularly those with higher ALT, a measure of hepatic fat accumulation.23 It must be recognized, however, that the issue of the NAFLD as a marker of more advanced carotid atherosclerosis is controversial24 and our data cannot provide any evidence in favor or against that possibility since we have no information about the liver status of our patients.

GGT, CIMT, and MetS

The clustering of elevated GGT and ALT levels with higher BMI, FPG, triglycerides, and BP by the NCEP-ATP III definition of MetS10 agrees with the findings of previous epidemiological observations25 linking the liver, the primary source of those enzymes,17,18 to a biological phenotype at high risk of CVD and diabetes.26 In concordance with previous studies27,28 based on similar diagnostic criteria,10 we found evidence of more advanced subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with MetS. More importantly, in light of our specific aims, the persistence of that difference after accounting for GGT implies an overcoming influence of metabolic abnormalities on atherosclerotic progression, which is fully concordant with other studies.29,30

Limitations of the study

The conclusions of our study must be considered in the context of some important limitations. First and more importantly, cross-sectional studies such as this one may establish associations or lack thereof, but are weak tools for assessing mechanistic links. Second, the common carotid arteries might be less prone to atherosclerosis than the bulb or the internal carotid arteries31 and the impact of cardiovascular risk factors may differ across carotid segments.32 Moreover, carotid plaques, which were not considered in our study, could relate to GGT more tightly than CIMT16 as a reflection of different biological and genetic determinants of the atherosclerotic process.33 Third, the pervasive use of statins as well as ACEIs and ARBs – a group of drugs endowed with pleiotropic anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties34,35 – may have obscured associations discernible in untreated conditions. That source of confounding is impossible, however, to be circumvented in retrospective studies as ours. Fourth, circulating GGT includes several heterogeneous molecular fractions that are undifferentiated by routine assays of which only the b-fraction may be associated with cardiovascular risk factors and may penetrate the atherosclerotic plaque.36 Fifth, the impact of GGT on CIMT may only be evident in patients with pathological GGT elevations that were excluded from our series to avoid confounding from liver disease other than NAFLD, given the absence of ultrasound or biopsy verification. However, this possibility applies, by definition, to a minority of subjects.

In conclusion, higher GGT values bore no relationship to common carotid IMT, a surrogate measure of atherosclerotic vascular disease, in this large group of high-risk subjects. The data do not support the concept of a pathophysiological link between GGT levels within reference limits and atherosclerotic involvement although further studies are needed to evaluate this possibility.

Footnotes

Author contributions

MN measured CIMT, PS and CG retrieved data from clinical records, GDO supervised clinical processing, AB provided input to result interpretation, RP wrote the paper and acted as senior author.

Disclosure

The authors have no actual or potential conflict of interests including any financial, personal, or other relationships with people or organizations within 3 years of beginning the work submitted that could inappropriately influence their work.

References

- 1.Whitfield JB. Gamma glutamyl transferase. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2001;38:263–355. doi: 10.1080/20014091084227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wannamethee G, Ebrahim S, Shaper AG. Gamma-glutamyltransferase: determinants and association with mortality from ischemic heart disease and all causes. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:699–708. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee DH, Jacobs DR, Jr, Gross M, et al. Gamma-glutamyltransferase is a predictor of incident diabetes and hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1358–1366. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM. Gamma-glutamyl transferase: another biomarker for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:4–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000253905.13219.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drozdz R, Parmentier C, Hachad H, Leroy P, Siest G, Wellman M. Gamma-glutamyltransferase-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species from a glutathione/transferrin system. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:786–792. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paolicchi A, Emdin M, Ghliozeni E, et al. Human atherosclerotic plaques contain gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase enzyme activity. Circulation. 2004;109:1440–1443. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120558.41356.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pignoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, Oreste P, Paoletti R. Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: a direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation. 1986;74:1399–1406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.6.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Leary DH, Bots ML. Imaging of atherosclerosis: carotid intima-media thickness. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1682–1689. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Careggi - Firenze S.O.D. Sicurezza e Qualità. VEQ – Valutazione esterna di Qualità. [Accessed April 12, 2012]. Available from: http://www.ao-careggi.toscana.it/crrveq/

- 10.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dell’Omo G, Penno G, Del Prato S, Mariani M, Pedrinelli R. Dysglycaemia in non-diabetic hypertensive patients: comparison of the impact of two different classifications of impaired fasting glucose on the cardiovascular risk profile. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:332–338. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown WV. Safety of statins. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:558–562. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328319baba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagmur J, Ermis N, Acikgoz N, et al. Elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transferase activity in patients with cardiac syndrome X and its relationship with carotid intima media thickness. Acta Cardiol. 2010;65:515–519. doi: 10.1080/ac.65.5.2056237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eroglu S, Sade LE, Polat E, Bozbas H, Ulus T, Muderrisoglu H. Association between serum gamma-glutamyltransferase activity and carotid intima-media thickness. Angiology. 2011;62:107–110. doi: 10.1177/0003319710386471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa H, Isogawa A, Tateishi R, et al. Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase level is associated with serum superoxide dismutase activity and metabolic syndrome in a Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:187–194. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volzke H, Robinson DM, Kleine V, et al. Hepatic steatosis is associated with an increased risk of carotid atherosclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1848–1853. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1221–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanni E, Bugianesi E, Kotronen A, De Minicis S, Yki-Järvinen H, Svegliati-Baroni G. From the metabolic syndrome to NAFLD or vice versa? Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKimmie RL, Daniel KR, Carr JJ, et al. Hepatic steatosis and subclinical cardiovascular disease in a cohort enriched for type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Heart Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3029–3035. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petit JM, Guiu B, Terriat B, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver is not associated with carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4103–4106. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvi P, Ruffini R, Agnoletti D, et al. Increased arterial stiffness in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Cardio-GOOSE study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1699–1707. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833a7de6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poanta LI, Albu A, Fodor D. Association between fatty liver disease and carotid atherosclerosis in patients with uncomplicated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Ultrason. 2011;13:215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schindhelm RK, Diamant M, Dekker JM, Tushuizen ME, Teerlink T, Heine RJ. Alanine aminotransferase as a marker of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in relation to type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2006;22:437–443. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1341–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilssen O, Førde OH, Brenn T. The Tromsø Study. Distribution and population determinants of gamma-glutamyltransferase. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:318–326. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckel RH. Mechanisms of the components of the metabolic syndrome that predispose to diabetes and atherosclerotic CVD. Proc Nutr Soc. 2007;66:82–95. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzou WS, Douglas PS, Srinivasan SR, et al. Increased subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults with metabolic syndrome: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassinen M, Komulainen P, Lakka TA, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the progression of carotid intima-media thickness in elderly women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:444–449. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HC, Kim DJ, Huh KB. Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and carotid intima-media thickness according to the presence of metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:521–525. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koskinen J, Magnussen CG, Kähönen M, et al. Association of liver enzymes with metabolic syndrome and carotid atherosclerosis in young adults. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Ann Med. 2012;44(2):187–195. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.532152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finn AV, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Correlation between carotid intimal/medial thickness and atherosclerosis: a point of view from pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:177–181. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polak JF, Person SD, Wei GS, et al. Segment-specific associations of carotid intima-media thickness with cardiovascular risk factors: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Stroke. 2010;41:9–15. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spence JD. Technology Insight: ultrasound measurement of carotid plaque – patient management, genetic research, and therapy evaluation. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:611–619. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Del Fiorentino A, Cianchetti S, Celi A, Dell’Omo G, Pedrinelli R. The effect of angiotensin receptor blockers on C-reactive protein and other circulating inflammatory indices in man. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:233–242. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Genser B, Grammer TB, Stojakovic T, Siekmeier R, März W. Effect of HMG CoA reductase inhibitors on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and C-reactive protein: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46:497–510. doi: 10.5414/cpp46497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franzini M, Paolicchi A, Fornaciari I, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and gamma-glutamyltransferase fractions in healthy individuals. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48:713–717. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2010.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]