Abstract

Background

The Model of Health Care Empowerment (HCE) defines HCE as the process and state of being engaged, informed, collaborative, committed, and tolerant of uncertainty regarding health care. We examined the hypothesized antecedents and clinical outcomes of this model using data from ongoing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related research. The purpose of this paper is to explore whether a new measure of HCE offers direction for understanding patient engagement in HIV medical care. Using data from two ongoing trials of social and behavioral aspects of HIV treatment, we examined preliminary support for hypothesized clinical outcomes and antecedents of HCE in the context of HIV treatment.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional analysis of 12-month data from study 1 (a longitudinal cohort study of male couples in which one or both partners are HIV-seropositive and taking HIV medications) and 6-month data from study 2, a randomized controlled trial of HIV-seropositive persons not on antiretroviral therapy at baseline despite meeting guidelines for treatment. From studies 1 and 2, 254 and 148 participants were included, respectively. Hypothesized antecedents included cultural/social/environmental factors (demographics, HIV-related stigma), personal resources (social problem-solving, treatment knowledge and beliefs, treatment decision-making, shared decision-making, decisional balance, assertive communication, trust in providers, personal knowledge by provider, social support), and intrapersonal factors (depressive symptoms, positive/negative affect, and perceived stress). Hypothesized clinical outcomes of HCE included primary care appointment attendance, antiretroviral therapy use, adherence self-efficacy, medication adherence, CD4+ cell count, and HIV viral load.

Results

Although there was no association observed between HCE and HIV viral load and CD4+ cell count, there were significant positive associations of HCE scores with likelihood of reporting a recent primary care visit, greater treatment adherence self-efficacy, and higher adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Hypothesized antecedents of HCE included higher beliefs in the necessity of treatment and positive provider relationships.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, health care empowerment, adherence, compliance

Background

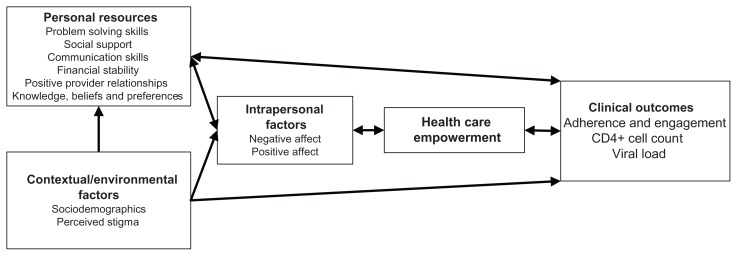

The model of health care empowerment (HCE) was recently proposed as a structure for understanding and intervening in how people perceive their participation in health care.1 The construct of HCE, defined as the state and process of being engaged, informed, committed, tolerant of uncertainty, and collaborative in one’s interactions with health care, offers direction for addressing differences in health care service utilization and outcomes across a wide range of populations and illnesses. The model hypothesizes that HCE is influenced through a dynamic interplay of contextual/environmental factors (such as age, race, and stigma), personal resources (such as finances, adaptive beliefs about treatment, problem-solving skills, and trust in providers), and intrapersonal processes and states (such as depressive symptoms and positive affect).

The treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is one example of a medical context that offers a rich opportunity to illustrate the potential applicability of HCE. HIV disease in the US and other developed countries is a heavily stigmatized condition that disproportionately affects populations who are economically and socially marginalized, including members of racial and ethnic minority groups, gay and transgender persons, and people with substance abuse histories.2–4 Treatment guidelines and antiretroviral therapy options are rapidly changing, and treatments have been historically difficult to tolerate, yet require vigilant adherence to prevent development of viral resistance, hastening of disease progression, and increased likelihood of the transmission of drug-resistant HIV to others.5–7

The purpose of this paper is to present preliminary support for the construct of HCE in the context of HIV treatment, with a particular emphasis on evaluating whether scores on a new measure of HCE are associated with hypothesized antecedents and clinical outcomes. Data from two ongoing studies of social and behavioral aspects of HIV treatment offer empirical evidence and direction for future indepth studies of HCE in HIV and other illnesses in which patient involvement in ongoing treatment is critical yet variable.

Materials and methods

A new measure of HCE was included in assessment batteries for two ongoing studies of social and behavioral factors of HIV treatment. Study 1 is a longitudinal cohort study of male couples in which one or both partners are HIV-seropositive and taking antiretroviral therapy. Couples are interviewed every 6 months for 2 years. HCE was assessed at the 12-month assessment wave as part of a comprehensive survey and blood was drawn for CD4+ cell count and HIV viral load. Study 2 is a randomized controlled trial of HIV-seropositive persons who were not on antiretroviral therapy at baseline despite meeting HIV treatment guidelines on CD4+ cell count cutoff for initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ie, ≤500 cells/mm3).8 HCE was assessed at the 6-month assessment wave as part of a comprehensive survey and blood drawn for CD4+ cell count and HIV viral load.

Participants and procedures

Recruitment for both studies included outreach to clinics and agencies, and posting of advertisements and flyers in the San Francisco Bay area community. HIV-positive serostatus was verified by HIV antibody testing or provision of documentation by potential participants, and antiretroviral therapy regimens were verified by examination of prescribed medication vials or official medication lists from the dispensing pharmacy. Participants provided written informed consent and all procedures were approved by the local institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco. Combinations of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing and computer-assisted personal interviewing were used to optimize self-report, to minimize data collection errors, and to facilitate efficient data management.9 Screening, data collection, and phlebotomy procedures occurred in private areas of research facilities and all participants were compensated for their involvement.

Measures

Participants in both studies were asked about general demographic information and HIV treatment history, including time since HIV diagnosis and past medical treatment details. The following variables were assessed in at least one of the two studies and are organized according to their hypothesized role as informed by the HCE model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mode1 of health care empowerment.

Health care empowerment

The 27-item measure of HCE was developed specifically by the investigators to assess the five hypothesized domains of health care empowerment: informed (five items, sample item “I am knowledgeable about my health condition(s)”); committed (six items, sample item “I am determined to work hard to get the most out of my health care”); collaborative (six items, sample item “I think of my health care providers as my partners in dealing with my health condition[s]”); engaged (five items, sample item “Others would probably say that I am a very engaged and active patient”); and tolerant of uncertainty (five items, sample item “I have learned to live with the uncertainty of my health condition”). Responses include five choices ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” and a global score is created by summing responses to all individual items. Cronbach’s alphas of 0.94 and 0.96 were calculated for study 1 and study 2, respectively, demonstrating acceptable internal reliability, and 6-month test-reliability estimates of 0.73 were available for study 1. This is the first publication to use this new measure.

Hypothesized clinical outcomes of HCE

To examine hypothesized proximal and downstream clinical consequences of HCE, the following data were analyzed (study 1 and/or study 2 indicate in which study the measure was administered), and reported alphas are for the current samples.

Primary care appointment attendance (study 1 and study 2): failure to consistently attend clinic appointments has been linked to poor virological control.10,11 We documented the time since most recent primary care visit and, for consistency between the two studies, classified all participants as having a primary care visit within the prior 3 months or not.

Antiretroviral therapy use (study 2): whether participants had initiated antiretroviral therapy during the follow-up period was documented for study 2 participants, all of whom met criteria for antiretroviral therapy initiation per HIV treatment guidelines8 at study enrollment.

Adherence self-efficacy (study 1 and study 2): adherence self-efficacy, or confidence in one’s ability to comply with a treatment plan, has been consistently linked to medication adherence over time.12,13 The HIV- Adherence Self Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES) assesses patient confidence in carrying out health-related behaviors (eg, asking physician questions, keeping appointments, adhering to medication).14 This measure includes two subscales, ie, integration and perseverance; α = 0.91 and 0.78, respectively, for study 1, and α = 0.91 and 0.65, respectively, for study 2.

Medication adherence (study 1 and study 2): adherence to antiretroviral medications was assessed using two well validated measures of self-report. The adherence measure developed to assess adherence in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group15 solicits detailed information about self-reported adherence over the previous 3 days. Adherence scores on this scale have been correlated with viral load.15,16 Second, a visual analog scale was administered,17 which assesses 30-day adherence reporting separately for each drug along a continuum anchored by “0%” to “100%.” This measure has been shown to be correlated with other adherence measures, such as electronic medication monitors.18,19 The 3-day adherence measure was dichotomized as 100% versus <100% adherence and the 30-day visual analog scale adherence is reported as a continuous variable.

CD4+ cell count and viral load (study 1 and study 2): HIV viral load was determined using the COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HIV test kit (Roche Molecular Systems Inc, Pleasanton, CA), which has a threshold for undetectability ≤20 copies/mL. A detectable viral load indicates incomplete viral suppression, or inadequately controlled HIV infection. CD4+ cell count provides a gauge of immune functioning, with lower counts typically indicating longer infection and/or greater immune system deterioration. In healthy persons, the normal range of CD4+ cell count is 500–1500 cells/mm3 of blood, and current HIV treatment guidelines recommend offering antiretroviral therapy to all HIV-seropositive persons with a CD4+ cell count below 500.8

Hypothesized antecedents of HCE

HCE is hypothesized to be related to three categories of variables, ie, cultural/social/environmental factors, personal resources (both material and psychological), and intrapersonal factors.

Cultural/social/environmental factors

Demographics (study 1 and study 2): including age, gender, race, and ethnicity were assessed via interview. HIV-related stigma (study 2) is believed to be a strong driver of HIV risk and treatment outcomes, and is often cited when discussing the sources of HIV-related disparities.20–27 HIV stigma (study 2) was assessed using the four-item distancing subscale of a stigma scale developed by Sowell, which assesses perceived distancing from others due to HIV-positive status (α = 0.90).26,28

Personal resources

Social problem-solving (study 1): investigated using the Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised questionnaire, 29,30 a 25-item, self-administered questionnaire that assesses problem orientation (negative and positive), problem-solving styles (avoidant and impulsive/careless), and rational problem-solving skills. The measure has been widely used, has been predictive of health and risk behaviors,31 and has shown meaningful relationships with antiretroviral therapy adherence in our prior work.32 As before, we combined the positive problem-solving scores into a constructive problem-solving scale (α = 0.82) and the negative problem-solving scales into a dysfunctional problem-solving scale (α = 0.85).

Treatment knowledge (study 2): a 16-item HIV treatment knowledge assessment was administered, with higher scores reflecting more accurate knowledge of aspects of treatment such as adherence, side effects, and drug resistance (α = 0.83).33

Treatment beliefs (study 1 and study 2): assessed using the HIV version of the Beliefs About Medications Questionnaire,34 which includes subscales of treatment necessity (α = 0.84 and 0.82) and treatment concerns (α = 0.66 and 0.72).

Preference for treatment decision-making (study 1): The 6-item Autonomy Preference Index specifically assesses patient preferences for shared medical decision-making (α = 0.67), with good evidence of concurrent and criterion validity.35 Higher scores reflect stronger preferences for patient involvement in treatment decision-making.

Opportunity for shared decision-making (study 1): The 3-item Decision-Making Opportunity Scale36 assesses how often a provider discusses the pros and cons of each medical care choice, elicits statements of patient preference, and takes patient preference into account when making treatment decisions (α = 0.85). Higher scores indicate a patient’s perception of greater opportunity for involvement, as enabled by the provider.

Decisional balance (study 1 and study 2): A single item by Beach et al37 assessing decisional balance preference was administered, ie, “Which best describes how decisions about your HIV treatment are made during your visits with your HIV care provider?” Response choices are 0 (“Provider makes most or all of the decisions”) 1 (“Provider and I make the decisions together”), and 2 (“I make most or all of the decisions”). Higher scores indicate a patient’s perception of greater involvement in treatment decisions.

Assertive communication (study 2): assessed with the 5-item Patient Communication Index scale of the Patient Reactions Questionnaire, with higher scores indicating greater difficulty with assertive communication with providers (α = 0.92).38

Positive provider interactions (study 2): The Positive Patient-Provider Interaction scale39 assesses the degree to which recent patient-provider interactions were seen as constructive by patients (α = 0.95).

Trust in providers (study 2): The 11-item Trust in Physician Scale40 assesses patients’ interpersonal trust in their provider and has been used in the context of HIV treatment (α = 0.74).41

Personal knowledge by provider (study 1 and study 2): A single item, ie, “My provider really knows me as a person.” In previous work, higher agreement with this statement was linked with greater antiretroviral therapy uptake and adherence.37

Social support (study 2): The Social Provisions Scale42 assesses level, type, and perceived satisfaction with social support from one’s social network. For the current analysis, we used the overall score, with higher values representing greater perceived social support (α = 0.91).

Intrapersonal factors

Depressive symptoms (study 1 and study 2): the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)43 was administered to measure depressed mood in the past week. The CES-D consists of 20 items rated on a 4-point scale according to how frequently they were experienced in the previous week (α = 0.92 and 0.92).

Positive and negative affect (study 1): We administered the Differential Emotions Scale44,45 which assesses 60 emotions of varied valence rated on a 5-point scale according to how frequently they were experienced in the past week. The scale was scored for total positive (α = 0.90) and negative affect (α = 0.86).

Perceived stress (study 2): Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale46 assesses the degree to which a person describes situations in the prior month as stressful. A total score is provided by summing ratings on a 5-point scale (α = 0.86), with higher scores indicating greater reports of distress.

Data analysis

The reported analyses were exploratory and guided by the model of HCE.1 The first analytic goal was to explore unadjusted associations of HCE with hypothesized clinical outcomes of HCE, eg, HIV biomarker measures of adherence as well as self-reported subjective measures of adherence self-efficacy. These include proximal and distal or downstream indicators of active, empowered engagement in medical treatment. The second goal was to use existing data to explore bivariate and multivariate associations of hypothesized antecedents of HCE. For each study, initial analyses described frequencies for categorical variables and measures of central tendency (median) and variability (standard deviations) for continuous variables. Bivariate analyses correlated HCE scale scores with clinical biomarker and self-report data, contextual/environmental factors, personal resource factors, and intrapersonal factors. Contextual/environmental, personal, and intrapersonal factors for which bivariate associations with HCE were significant at P < 0.25 were included in multivariable regression models explaining HCE in each study.47 Beginning with the least significant explanatory variable, the hypothesized contextual/environmental, personal, and intrapersonal antecedents were removed until all remaining correlates in adjusted analyses were significant at P < 0.05 (ie, backward elimination).48 SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used to generate descriptive statistics; Mplus version 6 (Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) was used to generate bivariate and adjusted analysis results via full information maximum likelihood, which makes use of all available information in the data to obtain optimal parameter estimates and standard errors when one or more cases have incomplete data.49 This method prevents different sample sizes being used for the backward elimination procedure for multivariable regression analyses due to some participants missing information on one or more measures. Bivariate (ie, unadjusted) correlations were reported using the r statistic. Adjusted coefficients from multivariable regression models were reported using the standardized regression coefficient, β, to quantify the amount of change per standard deviation in HCE as a function of each explanatory variable in the context of other significant correlates of HCE.

Results

Sample characteristics for participants in both studies are provided in Table 1. Study 2 participants included a greater proportion of African Americans, reported lower income and education, and were more likely to report histories of homelessness and injection drug use. Due to differences in study eligibility criteria, study 2 included more women and heterosexuals, and study 1 participants were more likely to have higher CD4+ cell counts and an undetectable viral load.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Study 1 (n = 254) | Study 2 (n = 148) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 45.4 ± 9.6 | 44.5 ± 8.1 | 0.51 |

| Percent male | 254 (100.0) | 121 (81.8) | <0.0001 |

| Race | – | – | <0.0001 |

| Black/African American | 45 (17.8) | 73 (49.3) | – |

| White | 135 (53.2) | 48 (32.4) | – |

| Other | 74 (29.1) | 27 (18.2) | – |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 46 (18.1) | 16 (10.8) | 0.05 |

| Sexual orientation | – | – | <0.0001 |

| Heterosexual | 2 (0.8) | 46 (31.1) | – |

| Homosexual | 229 (90.2) | 72 (48.7) | – |

| Bisexual/other | 23 (9.1) | 30 (20.3) | – |

| Education | – | – | <0.0001 |

| <High school | 12 (4.7) | 32 (21.6) | – |

| High school | 64 (25.2) | 59 (39.9) | – |

| Some college | 74 (29.1) | 42 (28.4) | – |

| College graduate | 104 (40.9) | 15 (10.1) | – |

| Income <US$20,000 | 134 (52.8) | 120 (88.5) | <0.0001 |

| Ever homeless or lived in shelter | 71 (28.0) | 108 (74.0) | <0.0001 |

| History of injection drug use | 82 (32.3) | 73 (49.3) | 0.0007 |

| CD4 count | – | – | <0.0001 |

| <200 | 19 (7.5) | 45 (30.4) | – |

| 200–500 | 93 (36.6) | 84 (56.8) | – |

| >500 | 142 (55.9) | 19 (12.8) | – |

| Viral load undetectable (%) | 134 (53.4) | 20 (14.0) | <0.0001 |

| Months since HIV+ mean (SD) | 154.5 (94.4) | 135.6 (89.6) | 0.05 |

| Health care empowerment, mean (SD) | 113.7 (12.2) | 103.3 (19.0) | <0.0001 |

Note: Comparisons were made using Pearson’s Chi-square test for binary, nominal, and ordinal variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Hypothesized clinical outcomes of HCE

Examination of hypothesized clinical outcomes of HCE in study 1 resulted in significant positive associations of HCE scores with likelihood of reporting a primary care visit in the previous 3 months (r = 0.29, P = 0.001), greater adherence self-efficacy integration (r = 0.39, P < 0.001) and perseverance scores (r = 0.33, P < 0.001), higher 3-day antiretroviral therapy adherence (r = 0.21, P = 0.004), and higher 30-day antiretroviral therapy adherence (r = 0.23, P = 0.001). In study 2, there was a similar pattern, in which higher HCE scores were reported by those reporting primary care visits in the prior 3 months (r = 0.25, P = 0.003), those with higher adherence self-efficacy integration scores (r = 0.26, P < 0.001), and those with higher 30-day antiretroviral therapy adherence reports (r = 0.27, P = 0.002). Unlike study 1, there was no association between HCE scores and adherence self-efficacy perseverance and 3-day antiretroviral therapy adherence. HCE was not associated with CD4 or viral load in either sample (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Hypothesized clinical correlates of health care empowerment

| Clinical correlate | Study 1 | Study 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| r (95% CI) | P | r (95% CI) | P | |

| On ART | – | – | 0.07 (−0.10, 0.23) | 0.43 |

| Primary care appointment last 3 months | 0.29 (0.12, 0.46) | 0.001 | 0.25 (0.08, 0.41) | 0.003 |

| Adherence self-efficacy: integration | 0.39 (0.28, 0.49) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.12, 0.41) | <0.001 |

| Adherence self-efficacy: perseverance | 0.33 (0.22, 0.43) | <0.001 | 0.08 (−0.10, 0.27) | 0.38 |

| Three-day 100% ART adherence | 0.21 (0.07, 0.35) | 0.004 | 0.14 (−0.07, 0.34) | 0.19 |

| Thirty-day ART adherence | 0.23 (0.10, 0.37) | 0.001 | 0.27 (0.10, 0.43) | 0.002 |

| CD4+ cell count | 0.02 (−0.10, 0.14) | 0.70 | 0.14 (−0.02, 0.30) | 0.08 |

| Detectable viral load | −0.08 (−0.21, 0.04) | 0.19 | 0.03 (−0.16, 0.20) | 0.79 |

Notes: n = 254 for study 1; n = 148 for study 2. All coefficients were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood in Mplus 6. All coefficients are standardized with binary correlates standardized on health care empowerment only and continuous correlates standardized on both health care empowerment and the correlates; coefficients may be interpreted as bivariate correlations. All inferences were generated using robust variance estimation (Mplus estimator MLR), with confidence intervals and test statistics additionally corrected for nesting of participants within couples in study 1.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; MLR, maximum likelihood with robust standard errors and test statistics.

Hypothesized antecedents of HCE

Although there was a positive bivariate relationship between age and higher HCE scores in study 1 (r = 0.15, P = 0.01), none of the contextual/social/background variables were significant in the adjusted models for either study 1 or study 2 (see Tables 3 and 4). In the adjusted model for study 1, several personal resource factors were associated with higher HCE, including higher constructive problem solving (β = 0.17, P = 0.01) and lower dysfunctional problem solving (β = −0.28, P = 0.01), higher beliefs in the necessity of treatment (β = 0.14, P = 0.02), higher reports of involvement in treatment decision-making (β = 0.19, P < 0.001), higher scores on the Autonomy Preference Index (β = 0.22, P < 0.001), and perceptions that the provider knows the patient as a person (β = 0.27, P < 0.001). In study 2, adjusted analyses revealed a positive association with beliefs in treatment necessity (β = 0.27, P = 0.01) and perceptions of recent positive provider interactions (β = 0.25, P = 0.004), and an association of lower HCE with greater difficulty with assertive communication with providers (β = −0.31, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Hypothesized antecedents of health care empowerment (study 1, n = 254)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| r (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Contextual/environmental factors | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | χ2(3) = 1.91a | 0.59 | – | – |

| White (non-hispanic, reference) | – | – | – | – |

| Black (non-hispanic) | 0.04 (−0.07, 0.15) | 0.47 | – | – |

| Hispanic | −0.01 (−0.13, 0.11) | 0.87 | – | – |

| Other race | −0.11 (−0.27, 0.05) | 0.19 | – | – |

| Age | 0.15 (0.04, 0.26) | 0.01 | – | – |

| Personal resource factors | ||||

| Income <US$20,000 | 0.04 (−0.09, 0.16) | 0.55 | – | – |

| Relationship satisfaction (CSI) | 0.05 (−0.09, 0.18) | 0.52 | – | – |

| Social problem solving (constructive) | 0.39 (0.26, 0.52) | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.05, 0.29) | 0.01 |

| Social problem solving (dysfunctional) | −0.36 (−0.50, −0.21) | <0.001 | −0.28 (−0.43, −0.12) | <0.001 |

| Need for BMQ | 0.21 (0.10, 0.33) | <0.001 | 0.14 (0.02, 0.25) | 0.02 |

| BMQ concerns | −0.05 (−0.18, 0.08) | 0.49 | – | – |

| Shared decision-making | 0.26 (0.12, 0.40) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.09, 0.30) | <0.001 |

| Provider knows me as a person | 0.32 (0.20, 0.43) | <0.001 | 0.27 (0.17, 0.37) | <0.001 |

| Autonomy preference index | 0.24 (0.09, 0.39) | 0.001 | 0.22 (0.10, 0.34) | <0.001 |

| Decision-making opportunity scale | 0.39 (0.21, 0.56) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Intrapersonal factors | ||||

| Depression | −0.18 (−0.30, −0.06) | 0.004 | 0.25 (0.10, 0.41) | 0.001 |

| DES positive emotion | 0.34 (0.22, 0.47) | <0.001 | 0.28 (0.13, 0.44) | <0.001 |

| DES negative emotion | −0.16 (−0.28, −0.04) | 0.01 | – | – |

Notes: All coefficients were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood in Mplus 6. All coefficients are standardized with binary correlates standardized on health care empowerment only and continuous correlates standardized on both health care empowerment and the correlates. Unadjusted coefficients may be interpreted as bivariate correlations; adjusted coefficients may be interpreted as standardized regression coefficients. All inferences were generated using robust variance estimation (Mplus estimator MLR) with confidence intervals and test statistics corrected for nesting of participants within couples.

Joint Wald significance test of race dummy variables.

Abbreviations: CSI, Couple Satisfaction Index; DES, Differential Emotions Scale; BMQ, Beliefs About Medications Questionnaire; MLR, maximum likelihood with robust standard errors and test statistics.

Table 4.

Hypothesized antecedents of health care empowerment, study 2 (n = 148)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| r (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Contextual/environmental factors | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | χ2(2) = 00.14a | 0.93 | – | – |

| White (non-hispanic, reference) | – | – | – | – |

| Black (non-hispanic) | −0.02 (−0.18, 0.14) | 0.81 | – | – |

| Hispanic and other races | −0.01 (−0.16, 0.14) | 0.92 | – | – |

| Age | −0.04 (−0.19, 0.12) | 0.65 | – | – |

| Female gender | −0.03 (−0.21, 0.16) | 0.78 | – | – |

| HIV stigma (distancing) | −0.03 (−0.21, 0.14) | 0.73 | – | – |

| Personal resource factors | ||||

| Income <US$10,000 | 0.16 (0.02, 0.30) | 0.03 | – | – |

| Social support (social provisions scale) | 0.40 (0.27, 0.53) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Treatment knowledge | 0.31 (0.14, 0.49) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Trust in provider | 0.33 (0.19, 0.47) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Need for BMQ | 0.30 (0.04, 0.55) | 0.02 | 0.27 (0.07, 0.48) | 0.01 |

| BMQ concerns | −0.23 (−0.42, −0.03) | 0.02 | – | – |

| Shared decision-making | −0.08 (−0.23, 0.08) | 0.35 | – | – |

| Provider knows me as a person | 0.22 (0.06, 0.38) | 0.01 | – | – |

| Patient reactions assessment | −0.48 (−0.62, −0.33) | <0.001 | −0.31 (−0.49, −0.14) | <0.001 |

| Positive provider interactions | 0.43 (0.30, 0.56) | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.08, 0.42) | 0.004 |

| Intrapersonal factors | ||||

| Depression | −0.20 (−0.36, −0.03) | 0.02 | – | – |

| Perceived stress | −0.09 (−0.25, 0.08) | 0.30 | – | – |

Notes: All coefficients were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood in Mplus 6. All coefficients are standardized with binary correlates standardized on health care empowerment only and continuous correlates standardized on both health care empowerment and the correlates. Unadjusted coefficients may be interpreted as bivariate correlations; adjusted coefficients may be interpreted as standardized regression coefficients. All inferences were generated using robust variance estimation (Mplus estimator MLR).

Joint Wald significance test of race dummy variables.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; BMQ, Beliefs About Medications Questionnaire; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MLR, maximum likelihood with robust standard errors and test statistics.

In study 1 adjusted analyses, higher HCE scores were associated with lower reported symptoms of depression (β = 0.25, P = 0.001) and higher reports of positive emotion (β = 0.28, P < 0.001). Depression and perceived stress were not associated with HCE scores in study 2.

Discussion

Findings from the two studies provide support for the model of health care empowerment in the context of HIV treatment. Consistent with the hypothesized role of HCE, greater patient empowerment was associated with reports of active participation in HIV care and perceived confidence in ability to adhere to treatment and self-reports of recent medication adherence. The association between HCE and laboratory markers of clinical status did not reach statistical significance, but this may be due to a restricted range on these variables, limited sample sizes, and the specific eligibility criteria regarding antiretroviral therapy use in the two studies.

The resulting correlates of HCE support a central role for knowledge, skills, provider relationships, and psychological well being in association with patient empowerment. From a research perspective, these findings offer direction for future in-depth studies of the role of empowerment. From a clinical perspective, findings suggest that providers who make efforts to get to know their patients beyond their clinical presentation, who strive to respect and foster patient autonomy, and who make concrete efforts to involve patients in decision-making may be effective in fostering health care empowerment in their patients. Interventions designed to improve patient skills in problem solving and assertive communication with providers edify treatment knowledge and reinforce a solid understanding for the need for prescribed treatments, and detect and treat depressive symptoms while fostering positive affect may promote greater patient empowerment and thus more productive engagement in care. Such improvements in empowerment may then facilitate better treatment utilization and adherence to antiretroviral therapy, resulting in more effective virological control and decreased HIV transmission to others.50,51

The pattern of hypothesized antecedents of HCE suggests no direct statistical association of contextual factors with empowerment scores, including stigma. Consistent with the model of HCE, it may be that these factors operate indirectly on empowerment by affecting other elements in the model, such as personal resources (eg, treatment knowledge) and intrapersonal factors (eg, depression). It is also likely that the samples recruited were not representative of the larger population on such measures as HIV stigma; those who are willing to enroll in ongoing research related to HIV might not be as sensitive or affected by HIV stigma as others who chose not to enroll. The limited sample sizes in this exploratory work precluded larger model testing through such procedures as structural equation modeling which could test simultaneous moderator and mediator effects.

Although generally consistent results were found between the two studies and the results were in the expected directions, the findings should be generalized with caution. The studies used convenience samples from one geographic area and relied primarily on self-reported measures, such as appointment attendance and medication adherence. Data are cross-sectional and thus cannot be used to determine causality. The 3-month time frame for the primary care visit variable may be too restrictive, because patients in stable clinical care may have less frequent but regular provider visits. The relatively modest sample sizes and limited variability of gender, age, race, and ethnicity preclude specific analysis of subgroups, and findings should thus be considered preliminary. Nonetheless, the pattern of findings across the two studies offers encouragement for further investigation of the model of health care empowerment.

In summary, our results reveal a rough map of the terrain of health care empowerment. Future investigations are needed to refine the measurement of the construct, to form and test new hypotheses, and to evaluate the fit of the construct and the model of health care empowerment in other illness settings and across cultures.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health grant numbers R01MH0790700, K24MH087220, K08 MH085566, and F32MH086323, National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research grant number R01NR011087, and NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI grant number UL1RR024131.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Portions of the findings of this research were presented by the principal author at the 6th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence on May 22–24, 2011, in Miami, FL, the Psychology Colloquium, University of Alabama at Birmingham, November 2, 2011, and the European Society of Patient Compliance, Adherence, and Persistence on November 18–19, 2011, Utrecht, The Netherlands. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Johnson MO. The shifting landscape of health care: Toward a model of health care empowerment. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):264–270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oramasionwu CU, Brown CM, Ryan L, Lawson KA, Hunter JM, Frei CR. HIV/AIDS disparities: the mounting epidemic plaguing US blacks. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1196–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oramasionwu CU, Brown CM, Lawson KA, Ryan L, Frei CR. Evaluating HIV/AIDS disparities for blacks in the United States: a review of antiretroviral and mortality studies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1221–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giami A, Le Bail J. HIV infection and STI in the trans population: a critical review. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2011;59(4):259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2011.02.102. French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volberding P, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):49–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNeil DG. Early HIV therapy sharply curbs transmission. New York Times. 2011 May 12; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-infected Adults and Adolescents. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services and the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280(5365):867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(11):1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Westfall AO, et al. Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(1):86–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318236f7d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, et al. Theory guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: Findings from the Healthy Living Project. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17(12):645–656. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sevelius JM, Carrico A, Johnson MO. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among transgender women living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth S, Morin SF, Remien RH, Chesney MA. The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES) J Behav Med. 2007;30(5):359–370. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9118-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee and Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chesney MA, Ickovics J. Adherence to combination therapy in AIDS clinical trials. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group; Washington DC. July 19–22, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh JC, Pozniak AL, Nelson MR, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Virologic rebound on HAART in the context of low treatment adherence is associated with a low prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(3):278–287. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200207010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS. 2002;16(2):269–277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyugi JH, Byakika-Tusiime J, Charlebois ED, et al. Multiple validated measures of adherence indicate high levels of adherence to generic HIV antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(5):1100–1102. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herek GM, Glunt EK. An epidemic of stigma: public reactions to AIDS. Am Psychol. 1988;43(11):886–891. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.11.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunting SM. Sources of stigma associated with women with HIV. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1996;19(2):64–73. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chesney MA, Smith AW. Critical delays in HIV testing and care: The potential role of stigma. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42(7):1162–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demarco FJ. Coping with the Stigma of AIDS: An Investigation of the Effects of Shame, Stress, Control and Coping on Depression in HIV-Positive and -Negative Gay Men (Immune Deficiency, Sexual Orientation) East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timberlake S, Sigurdson J. HIV, stigma, and rates of infection: a human rights and public health imperative. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao D, Kekwaletswe TC, Hosek S, Martinez J, Rodriguez F. Stigma and social barriers to medication adherence with urban youth living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2007;19(1):28–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120600652303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emlet CA. Measuring stigma in older and younger adults with HIV/AIDS: an analysis of an HIV stigma scale and initial exploration of subscales. Res Soc Work Pract. 2005;15(4):291–300. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Perkovich B, Johnson CV, Safren SA. A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Top HIV Med. 2009;17(1):14–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sowell RL, Lowenstein A, Moneyham L, Demi A, Mizuno Y, Seals BF. Resources, stigma, and patterns of disclosure in rural women with HIV infection. Public Health Nurs. 1997;14(5):302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1997.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Development and preliminary evaluation of the social problem-solving inventory. Psychol Assess. 1990;2(2):156–163. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maydeu-Olivares A, D’Zurilla TJ. A factor-analytic study of the social problem-solving inventory: an integration of theory and data. Cognit Ther Res. 1996;20(2):115–133. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott TR, Johnson MO, Jackson R. Social problem solving and health behaviors of undergraduate students. J Coll Stud Dev. 1997;38(1):24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson MO, Elliott TR, Neilands TB, Morin SF, Chesney MA. A social problem solving model of adherence to HIV medications. Health Psychol. 2006;25(3):355–363. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balfour L, Kowal J, Tasca GA, et al. Development and psychometric validation of the HIV Treatment Knowledge Scale. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1141–1148. doi: 10.1080/09540120701352241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire: The development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, Moskowitz MA. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy: decision making and information-seeking preferences among medical patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(1):23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02596485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harvey RM, Kazis L, Lee AF. Decision-making preference and opportunity in VA ambulatory care patients: association with patient satisfaction. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22(1):39–48. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199902)22:1<39::aid-nur5>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beach MC, Duggan PS, Moore RD. Is patients’ preferred involvement in health decisions related to outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1119–1124. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0241-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galassi JP, Schanberg R, Ware WB. The patient reactions assessment: A brief measure of the quality of the patient-provider medical relationship. Psychol Assess. 1992;4(3):346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson MO, Chesney M, Goldstein RB, et al. Positive provider interactions, adherence self-efficacy, and adherence to antiretroviral medications among HIV infected adults: A mediation model. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(4):258–268. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67(3 Pt 2):1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(1):47–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cutrona CE. Ratings of social support by adolescents and adult informants: Degree of correspondence and prediction of depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(4):723–730. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Izard CE. Human Emotions. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izard CE, Dougherty F, Bloxom BM, Kotsch NE. The Differential Emotions Scale: A Method of Measuring the Subjective Experience of Discrete Emotions. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski S, McCulloch CE. Regression Methods in Biostatistics. New York, NY: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]