Abstract

Comprehensive sequencing of tumor suppressor genes to evaluate inherited predisposition to cancer yields many individually rare missense alleles of unknown functional and clinical consequence. To address this problem for CHEK2 missense alleles, we developed a yeast-based assay to assess in vivo CHEK2-mediated response to DNA damage. Of 25 germline CHEK2 missense alleles detected in familial breast cancer patients, 12 alleles had complete loss of DNA damage response, 8 had partial loss and 5 exhibited a DNA damage response equivalent to that mediated by wild-type CHEK2. Variants exhibiting reduced response to DNA damage were found in all domains of the CHEK2 protein. Assay results were in agreement with epidemiologic assessments of breast cancer risk for those variants sufficiently common for case–control studies to have been undertaken. Assay results were largely concordant with consensus predictions of in silico tools, particularly for damaging alleles in the kinase domain. However, of the 25 variants, 6 were not consistently classifiable by in silico tools. An in vivo assay of cellular response to DNA damage by mutant CHEK2 alleles may complement and extend epidemiologic and genetic assessment of their clinical consequences.

INTRODUCTION

The availability of extensive genomic data from patients with inherited predisposition to disease poses the challenge of determining which genetic changes are causal for the disease phenotype. A frequent form of this challenge is to understand the clinical consequences of rare missense alleles. Missense alleles that are private or extremely rare cannot be individually evaluated by conventional epidemiologic and statistical methods. Instead, such alleles can be analyzed with approaches based on evolutionary conservation of sequence; on co-inheritance of the mutant with disease in a family, if the family is sufficiently large; and on experimental demonstration of the consequences of the variant to the function of the protein.

This challenge now arises for evaluation of inherited predisposition to breast and ovarian cancers, for which massively parallel sequencing of known tumor suppressor genes is available (1). We focus here on development of a functional assay to assist in interpretation of missense alleles in the cell cycle regulator CHEK2 (2). CHEK2 is a kinase that acts as a tumor suppressor gene. CHEK2 is the human homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad53, and like rad53, plays a critical role in the maintenance of genomic integrity by inducing cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage. In response to DNA damage, CHEK2 connects activated kinases ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein and ataxia telangiectasia and rad3-related protein with cell cycle checkpoint effectors and with the DNA repair machinery. CHEK2 phosphorylates BRCA1, whereupon BRCA1 represses the non-homologous end-joining pathway and activates the homologous recombination repair pathway (3–7). CHEK2 phosphorylates CDC25C and CDC25A, resulting in G1- and S-phase delay (8,9). CHEK2 phosphorylates p53, stabilizing it by disrupting the p53-MDM2 interaction (10) and leading to increased association of p53 with the histone deacetylase p300, which positively regulates p53 transcriptional activity (2).

Consistent with its biology, inherited loss-of-function mutations in CHEK2 predispose to cancer of the breast (11,12) and to cancer of other sites (13,14). Among women heterozygous for CHEK2 c.1100delC, breast cancer risk is increased ∼2-fold (15). Of inherited CHEK2 variants observed among breast cancer patients, CHEK2 c.1100delC and a few other variants clearly lead to the loss of function, but many variants are individually rare missense alleles (16,17). In families in our studies who are severely affected with breast cancer (i.e. families including at least four relatives with breast cancer at any age at diagnosis) (18), we have encountered thus far 25 such missense alleles, some previously reported and some observed for the first time in our series (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of CHEK2 variants by multiple in silico analysis tools and by the present in vivo assay of response to DNA damage

| Chr | Position (hg19) | NT | cDNAa | Proteina | Domain | rad53b | Align GVGDe | Poly Phen2c | PolyPhen2 prediction | SIFT | SIFT prediction | In silico consensusf | Present resultsg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 29,130,703 | G>A | c.7C>T | R3W | – | – | C25 | 0.97 | Probably damaging | – | nc | 0.69 | |

| 22 | 29,130,636 | A>G | c.74T>C | V25A | SQ/TQ | – | C0 | 0.00 | Benign | – | Benign | 0.74 | |

| 22 | 29,130,546 | G>A | c.158C>T | S53F | SQ/TQ | – | C65 | 0.30 | Benign | – | nc | 0.74 | |

| 22 | 29,130,534 | G>T | c.176C>A | T59K | SQ/TQ | – | C65 | 0.30 | Benign | – | nc | 0.51 | |

| 22 | 29,130,520 | C>T | c.190G>A | E64K | SQ/TQ | – | C15 | 0.17 | Benign | 0.54 | Tolerated | Benign | 0.02 |

| 22 | 29,130,456 | G>A | c.254C>T | P85L | – | – | C0 | 0.44 | Possibly damaging | 0.32 | Tolerated | Benign | 1.30 |

| 22 | 29,121,326 | C>T | c.349A>G | R117G | FHA | Yes | C65 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.00 | Damaging | Damaging | −0.08 |

| 22 | 29,121,265 | C>T | c.410G>A | R137Q | FHA | No | C0 | 0.01 | Benign | 0.55 | Tolerated | Benign | 1.02 |

| 22 | 29,121,247 | T>C | c.428A>G | H143R | FHA | Yes | C25 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.00 | Damaging | Damaging | −0.08 |

| 22 | 29,121,242 | G>A | c.433C>T | R145W | FHA | No | C65 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.04 | Damaging | Damaging | −0.08 |

| 22 | 29,121,087 | A>G | c.470T>C | I157T | FHA | No | C25 | 0.39 | Benign | 0.13 | Tolerated | Intermediate | 0.07 |

| 22 | 29,121,077 | T>C | c.480A>G | I160M | FHA | No | C0 | 0.83 | Possibly damaging | 0.03 | Damaging | nc | 0.52 |

| 22 | 29,121,058 | C>T | c.499G>A | G167R | FHA | Yes | C65 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.00 | Damaging | Damaging | −0.06 |

| 22 | 29,121,019 | G>A | c.538C>T | R180C | FHA | No | C25 | 0.81 | Possibly damaging | 0.00 | Damaging | nc | 0.64 |

| 22 | 29,121,016 | G>A | c.541C>T | R181C | FHA | No | C0 | 0.01 | Benign | 0.20 | Tolerated | Benign | 0.52 |

| 22 | 29,120,992 | T>C | c.565A>G | I189V | FHA | Yes | C25 | 0.82 | Possibly damaging | 0.15 | Tolerated | Intermediate | 0.04 |

| 22 | 29,107,974 | C>T | c.715G>A | E239K | Kinase | Yes | C15 | 0.14 | Benign | 0.16 | Tolerated | Intermediate | 0.58 |

| 22 | 29,095,917 | C>G | c.917G>C | G306A | Kinase | Yes | C55 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.11 | Tolerated | Damaging | −0.06 |

| 22 | 29,095,881 | C>T | c.953G>A | R318H | Kinase | No | C0 | 0.10 | Benign | 0.18 | Tolerated | Benign | 0.47 |

| 22 | 29,095,867 | T>G | c.967A>C | T323P | Kinase | No | C0 | 0.97 | Probably damaging | 0.28 | Tolerated | nc | 0.89 |

| 22 | 29,092,944 | T>G | c.1040A>C | D347Ad | Kinase | 0.00 | |||||||

| 22 | 29,092,914 | G>A | c.1070C>T | S357F | Kinase | No | C65 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.01 | Damaging | Damaging | −0.08 |

| 22 | 29,091,220 | A>G | c.1270T>C | Y424H | Kinase | No | C65 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.04 | Damaging | Damaging | −0.01 |

| 22 | 29,091,207 | G>A | c.1283C>T | S428F | Kinase | Yes | C15 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.00 | Damaging | Damaging | 0.10 |

| 22 | 29,090,054 | G>T | c.1427C>A | T476K | Kinase | Yes | C15 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.03 | Damaging | Damaging | 0.25 |

| 22 | 29,090,054 | G>A | c.1427C>T | T476M | Kinase | Yes | C15 | 1.00 | Probably damaging | 0.00 | Damaging | Damaging | −0.05 |

nc, no consensus.

aNM_007194.3 (mRNA), NP_009125.1 (protein); amino acid substitutions deduced from DNA sequences.

bYes indicates conservation of wild-type human residue and S. cerevisciae residue at this site.

cHumDiv from May 8, 2011 update of Polyphen2; default parameters.

dSynthetic mutation with the loss of kinase activity used as negative control [Matsuoka et al. (2)].

eOn align GVGD, C65 represents highest and C0 lowest genetic risk [Tavtigian et al. 2008 (32)]. Predictions were derived from the human CHEK2 alignment available on the website at the zebrafish depth.

fAn in silico consensus value was derived by comparing the predictions from each of the evaluated analysis tools. An in silico consensus value of ‘benign’ or ‘damaging’ required a majority prediction, otherwise ‘no consensus’ was reached. Exceptions, categorized as ‘intermediate’, were made when variants yielded moderate values close to the prediction cutoff guidelines that would otherwise yield a consensus.

gResults of the in vivo assay of response to DNA damage, normalized to scores of 1.00 for the wild-type human CHEK2 sequence and 0.00 for the D347A negative control.

Functional consequences of missense variants in the CHEK2 kinase domain have heretofore been evaluated by kinase assays involving transfection of epitope-tagged CHEK2 variants into cells containing endogenous wild-type CHEK2. A limitation of such assays is that upon activation, CHEK2 forms dimers, many of which contain endogenous wild-type CHEK2. Precipitation of CHEK2 mutants from these cells also yields wild-type CHEK2, obscuring assay results. A second limitation of this approach is that most kinase assays test phosphorylation of only a single substrate, usually Cdc25C, although CHEK2 is capable of recognizing and phosphorylating substrates with highly divergent recognition motifs (13,14,19). Given that a missense variant may disrupt activity against one substrate but not another, even a technically perfect kinase assay may not accurately predict the capacity of a mutant CHEK2 protein to mediate response to DNA damage.

The difficulties of interpretation of CHEK2 p.I157T illustrate these complexities. Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that CHEK2 p.I157T is damaging. Genetic and epidemiological data support an increased risk of breast cancer associated with this variant (20). In Chek2-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts transfected with human CHEK2 p.157T, the CHEK2 mutant protein is unable to dimerize, resulting in a complete lack of autophosphorylation (7). Subsequent solution of the crystal structure of CHEK2 and assessment of CHEK2 p.I157T in this context confirmed failure of the mutant protein to dimerize (6). In contrast, previous reports, based on transfection of CHEK2 p.I157T into cells expressing endogenous wild-type CHEK2, had indicated normal kinase activity for this variant (2,9–11). The most likely explanation for these discrepant results is that in cells harboring endogenous wild-type CHEK2, heterodimers of wild-type and transfected mutant CHEK2 proteins had essentially wild-type activity. These experiments, over more than a decade, reflect a great deal of work for a single mutation. Given that many missense variants appear in CHEK2, we undertook to develop an assay that could be easily carried out in yeast for any missense allele and would reflect loss or maintenance of a critical function of the wild-type CHEK2 protein.

RESULTS

DNA damage assay

In order to evaluate mutations in all parts of the CHEK2 gene with a single biological test, we developed an assay to evaluate CHEK2-mediated response to DNA damage. The assay is based on complementation of S. cerevisiae rad53 by human CHEK2. Yeast is absolutely dependent on rad53, both for survival and for recovery from stress (2). Wild-type human CHEK2 partially complements the loss of rad53 activity in these strains (2). In order to work with yeast strains lacking rad53, we used a strain that also includes disruption of the yeast gene sml, which encodes an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (21). When sml is disrupted, increased pools of dNTPs become available for DNA synthesis. For this assay, each CHEK2 missense variant was introduced into a yeast expression plasmid and subsequently introduced into yeast lacking rad53/sml. Protein expression was induced for 72 h and optical density (OD) readings were taken to ensure that all cultures were in late-log phase of growth. Cells were then diluted to an equal density and transferred to 96-well microplates. Six replicates were plated for each variant. DNA damage was generated by adding methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (22), resulting in cell cycle arrest within 48 h. In ∼72 h, yeast harboring wild-type CHEK2 re-entered the cell cycle, having repaired the MMS-induced damage. Growth of each variant was monitored from 72 to 96 h, with the endpoint for the experiment corresponding to mid-log phase for the yeast harboring wild-type CHEK2. The negative control for the assay was the kinase-dead missense mutation CHEK2 p.D347A, which was developed as a negative control for the original CHEK2 kinase assay (2).

Based on growth of the strain after DNA damage, each variant was scored as ‘benign’, ‘intermediate’ or ‘damaging’ (Fig. 1). Two to four independent experiments, each with six replicates, were carried out for each mutation (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Using Mann–Whitney U-tests, growth rates of strains carrying each mutant allele were compared with growth rates for wild-type CHEK2 and for the negative control. All comparisons were based on data obtained in simultaneous experiments. A variant was defined as ‘benign’ if its growth did not differ significantly from growth of wild-type CHEK2 and was significantly greater than growth of the negative control. A variant was defined as ‘damaging’ if its growth was significantly poorer than that of wild-type CHEK2 and did not differ significantly from growth of the negative control. A variant was defined as ‘intermediate’ if its growth was significantly poorer than wild-type CHEK2 and significantly greater than the negative control. In principle, a variant would have been defined as ‘indeterminate’ if its growth did not differ significantly from either wild-type CHEK2 or the negative control. However, all variants could be characterized as benign, intermediate or damaging; none was indeterminate. For each variant, relative growth was also scored quantitatively as the proportion of the difference in the growth rate of wild-type human CHEK2 and the growth rate of the negative control (Table 1, Fig. 1). In S. cerevisiae, the sensitivity of rad53 mutants to DNA damage can be suppressed by deletion of the EXO1 gene. To test that EXO1 was expressed in all cultures, we evaluated EXO1 expression by RT–polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Wild-type EXO1 message was expressed in all cultures, confirming that EXO1 was not deleted.

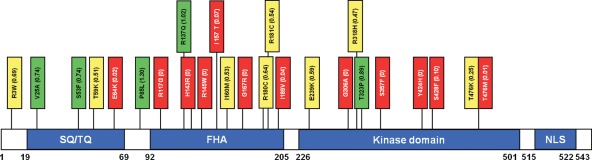

Figure 1.

CHEK2 missense variants by DNA damage response and protein domain. Missense variants are arranged by position on the CHEK2 protein and colored by CHEK2-mediated DNA damage response: similar to wild-type (green), loss of response (red) and intermediate response (yellow). A quantitative estimate of DNA damage response, normalized to wild-type CHEK2 and the negative control, is indicated in parentheses for each mutation.

Of the 25 rare missense alleles encountered in familial breast cancer patients in our series, 12 were damaging, 8 were intermediate and 5 were benign. The twelve variants with loss of function by the DNA damage response assay occurred in all domains of the CHEK2 protein. We speculate that some damaging variants destabilize the protein, others disrupt interactions with downstream effector proteins and others involve loss of kinase activity.

Pedigree analysis

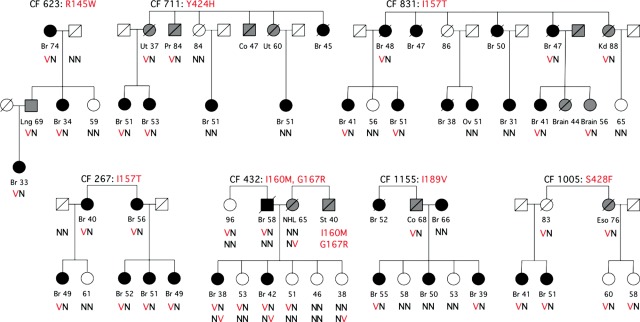

Co-segregation in families of seven CHEK2 missense alleles with breast and other cancers is shown in Figure 2. CHEK2 alleles p.R145W, p.I157T, p.I189V, p.Y424H and p.S428F were defined as damaging by the assay. Co-segregation of these alleles with breast cancer in families is consistent with expectation for damaging alleles of moderate penetrance. A particularly interesting case is family CF432, which harbors two CHEK2 missense alleles, p.I160M and p.G167R. Results of the DNA damage response assay indicate that p.G167R has no response to DNA damage and that p.I160M has a partial response. Two female relatives in this family with breast cancer diagnoses at ages 38 and 42 years are compound heterozygotes for both alleles; three as-yet-unaffected sisters are heterozygous for only one or the other of the two alleles. CHEK2 p.I160M was inherited from the father who had a diagnosis of breast cancer, but this allele was also present his elderly unaffected sister. CHEK2 p.G167R was inherited from the mother who died of non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Based on pedigree considerations alone, it was not possible to determine which allele(s) were damaging. A reasonable interpretation of these results is that both alleles may have played a role in the predisposition of the affected sisters, and that the youngest unaffected sister, who is heterozygous for p.G167R, should be considered at higher-than-normal risk.

Figure 2.

Co-inheritance of CHEK2 missense alleles with cancer in families. Informative relatives of extended families with loss-of-function alleles of CHEK2 are shown in the figure. Black symbols represent individuals with breast cancer. Grey symbols represent individuals with other cancers, including brain (Brain), colon (Co), esophagus (Eso), kidney (Kd), lung (Lng), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), ovary (Ov), pancreas (Pa), prostate (Pr), stomach (St) and uterus (Ut).

DISCUSSION

Concordance between results in the CHEK2-mediated DNA damage response assay and epidemiologic assessment of breast cancer risk is high for those CHEK2 missense variants for which case–control studies have been undertaken. In particular, risks of breast cancer associated with CHEK2 p.I157T and CHEK2 p.S428F are ∼2-fold (20,23), consistent with these alleles being defined as damaging by this assay. Conversely, CHEK2 p.P85L is known to be benign and polymorphic, consistent with the wild-type level of DNA damage response associated with this variant.

For several of the most well-characterized damaging variants in CHEK2, results of other functional assays suggest possible mechanisms for failure to repair damaged DNA. CHEK2 p.R117G is incompletely phosphorylated and hence has impaired activation (4). CHEK2 p.I157T and p.R145W fail to bind to and induce degradation of Cdc25A, abrogating the S-phase checkpoint (24). CHEK2 p.I157T fails to oligomerize or autophosphorylate (7). CHEK2 p.R145W is an unstable protein (10). CHEK2 p.S428F was previously shown not to complement loss of rad53 in S. cerevisceae (23).

Results of the functional assay and predictions based on in silico tools can be used to cross-validate each other (25). Furthermore, for clinical application, it is useful to know the conditions under which predictions of in silico tools are concordant with results of the functional assay. We compared results of the functional assay with predictions of Align-GVGD (26), PolyPhen-2 (27) and SIFT (28), and with alignment to conserved portions of the yeast rad53 protein sequence (2). In applying SIFT, we indicated a prediction only for sites at which at least 60% of sequences could be aligned (28). Since combining information from multiple in silico methods can improve predictive value (29), we assigned a consensus prediction to sites at which in silico approaches were in close agreement with each other. Of the 25 variants evaluated, there were 16 sites for which in silico approaches were in agreement (Table 1). Consensus in silico predictions were concordant with results of the functional assay at 12 of these 16 sites. The most striking discrepancies between a consensus prediction from in silico approaches and results of the functional assay were mutations p.E64K in the SQ/TQ domain and p.I157T in the FHA domain, which were predicted to be benign by in silico approaches but exhibit no response to DNA damage (Table 1). In addition to the functional assay, epidemiologic evidence for p.I157T also indicates that this mutation is damaging. We speculate that fewer alignable sequences in these domains, compared with the kinase domain, limit the predictive value of the in silico approaches for these sites. In contrast, for variants in the kinase domain for which in silico approaches were in agreement, results of the functional assay were also concordant. This pattern suggests that this functional assay may be most useful for missense mutations, anywhere in the CHEK2 protein, for which predictions by in silico tools either cannot be made with confidence or are not in agreement.

A potentially important issue raised by the results of the DNA damage response assay is the clinical consequence of partial loss of activity. Eight missense mutations had an intermediate response to DNA damage; that is, growth of these strains following DNA damage was significantly better than growth of the negative control, but significantly poorer than growth of strains carrying wild-type human CHEK2. It could be informative to evaluate co-segregation with breast cancer of these intermediate-activity mutations as a group, perhaps combining results across multiple families. It is also possible that breast cancer cases with these mutations may harbor a second predisposing allele as well, as in family CF432 (Fig. 2).

The discovery of rare missense substitutions in genes of potential medical importance will increase very rapidly as genomic sequencing becomes widespread in clinical practice. Among genes important to inherited predisposition to cancer, current indications for CHEK2 genetic testing are a strong family history of breast cancer in the absence of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (16). For the most thoroughly investigated CHEK2 loss-of-function alleles, women are at ∼25% lifetime risk of breast cancer (15). At this level of risk, the American Cancer Society recommends screening by MRI as an adjunct to mammography (30). A further complexity for genetic counseling of carriers of damaging variants is that CHEK2 is also associated with cancers other than breast (31).

In order to apply surveillance guidelines effectively, it is essential to be able to determine the consequences of novel variants. The development and application of straightforward functional assays, such as this one, can contribute to implementation of screening programs tailored to an individual's risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids

The yeast expression vectors: pBAD101, pMH267 (pBAD101, 2μ LEU2 GAL-CHEK2) and pMH269 [pBAD101, 2μ LEU2 GAL-CHEK2 (D347A)] were gifts from Elledge and co-authors (2). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange Lightning Kit (Agilent Technologies) to introduce mutations and all plasmids were fully sequenced to confirm the presence of the variant and the absence of PCR-induced mutations. The S. cerevisiae strain W2105-17b: MATa sml1::URA3 rad53::HIS3 was a gift from Rothstein and co-authors (21). Competent cells were created and transformed using the Frozen EZ Yeast Transformation Kit (Zymo Research).

DNA damage assay

Single colonies picked from His-Ura-Leu (HUL) plates were inoculated into HUL liquid media containing 2% galactose/raffinose (G/R) for ∼72 h or until they reached late-log phase. Cultures were diluted to an OD of 0.5 to adjust for differences in growth rate due to the selective growth advantage imparted by wild-type CHEK2 expression, and transferred to 96 well plates (∼2 × 105 cells/ well) in media containing HUL (G/R) with MMS (methyl methanesulfonate, Sigma) at a final concentration of 0.014%. Cultures were allowed to equilibrate at 30° for 48 h so that all cells have exited the cell cycle and OD measurements were recorded. Cultures were incubated at 30° for approximately another 48 h until wells containing wild-type CHEK2 reach an OD of 0.25, mid-log, for a total of 96 h. This value was selected to obtain maximal assay sensitivity while maintaining exponential growth rates. Experimental values were derived from subtracting the endpoint read from the values of the arrested cells at 48 h. Strains including wild-type CHEK2 plasmids and negative control plasmids were included in each experiment.

RNA isolation and sequencing

One milliliter of late-log phase culture was reserved from the cells used to seed the DNA damage experiment. RNA was prepared using the yeast enzymatic lysis protocol from the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was DNase-treated (Ambion) and cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III (Invitrogen). CHEK2 expression was assessed using primers against the full-length gene, utilized the yeast lsc2 gene as a control. CHEK2 mutations were confirmed by sequencing the PCR products.

Evaluation of possible splicing alterations

For each variant discovered in our lab, cDNA generated from RNA isolated from patient blood was Sanger sequenced to test for alterations of splicing. In addition, for all variants, we used in silico tools, as previously described (18), to evaluate the possibility of splice alterations, either by generation of new splice sites or by loss or addition of enhancers.

WEB RESOURCES

URLs for data and methods presented herein are as follows:

Align-GVGD, http://agvgd.iarc.fr/, (last accessed date on 20 March 2012).

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/, (last accessed date on 20 March 2012).

SIFT, http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/, (last accessed date on 20 March 2012).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and by NIH grants R01CA157744 and T32ES007032.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participating families for their decades-long commitment to this project. We also thank Elizabeth Swisher, Sean Tavtigian, Silvia Casadei and Tom Walsh for helpful comments.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walsh T., Lee M.K., Casadei S., Thornton A.M., Stray S.M., Pennil C., Nord A.S., Mandell J.B., Swisher E.M., King M.C. Detection of inherited mutations for breast and ovarian cancer using genomic capture and massively parallel sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:12629–12633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007983107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuoka S., Huang M., Elledge S.J. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282:1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirao A., Kong Y.Y., Matsuoka S., Wakeham A., Ruland J., Yoshida H., Liu D., Elledge S.J., Mak T.W. DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science. 2000;287:1824–1827. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sodha N., Mantoni T.S., Tavtigian S.V., Eeles R., Garrett M.D. Rare germ line CHEK2 variants identified in breast cancer families encode proteins that show impaired activation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8966–8970. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver A.W., Paul A., Boxall K.J., Barrie S.E., Aherne G.W., Garrett M.D., Mittnacht S., Pearl L.H. Trans-activation of the DNA-damage signalling protein kinase Chk2 by T-loop exchange. EMBO J. 2006;25:3179–3190. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai Z., Chehab N.H., Pavletich N.P. Structure and activation mechanism of the CHK2 DNA damage checkpoint kinase. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarz J.K., Lovly C.M., Piwnica-Worms H. Regulation of the Chk2 protein kinase by oligomerization-mediated cis- and trans-phosphorylation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2003;1:598–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chrisanthar R., Knappskog S., Lokkevik E., Anker G., Ostenstad B., Lundgren S., Berge E.O., Risberg T., Mjaaland I., Maehle L., et al. CHEK2 mutations affecting kinase activity together with mutations in TP53 indicate a functional pathway associated with resistance to epirubicin in primary breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X., Webster S.R., Chen J. Characterization of tumor-associated Chk2 mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2971–2974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S.B., Kim S.H., Bell D.W., Wahrer D.C., Schiripo T.A., Jorczak M.M., Sgroi D.C., Garber J.E., Li F.P., Nichols K.E., et al. Destabilization of CHK2 by a missense mutation associated with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8062–8067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell D.W., Varley J.M., Szydlo T.E., Kang D.H., Wahrer D.C., Shannon K.E., Lubratovich M., Verselis S.J., Isselbacher K.J., Fraumeni J.F., et al. Heterozygous germ line hCHK2 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Science. 1999;286:2528–2531. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollestelle A., Wasielewski M., Martens J.W., Schutte M. Discovering moderate-risk breast cancer susceptibility genes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010;20:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingvarsson S., Sigbjornsdottir B.I., Huiping C., Hafsteinsdottir S.H., Ragnarsson G., Barkardottir R.B., Arason A., Egilsson V., Bergthorsson J.T. Mutation analysis of the CHK2 gene in breast carcinoma and other cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4:R4. doi: 10.1186/bcr435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong X., Wang L., Taniguchi K., Wang X., Cunningham J.M., McDonnell S.K., Qian C., Marks A.F., Slager S.L., Peterson B.J., et al. Mutations in CHEK2 associated with prostate cancer risk. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:270–280. doi: 10.1086/346094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CHEK2 Breast Cancer Case-Control Consortium. CHEK2*1100delC and susceptibility to breast cancer: a collaborative analysis involving 10,860 breast cancer cases and 9,065 controls from 10 studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:1175–1182. doi: 10.1086/421251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narod S.A. Testing for CHEK2 in the cancer genetics clinic: ready for prime time? Clin. Genet. 2010;78:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Calvez-Kelm F., Lesueur F., Damiola F., Vallee M., Voegele C., Babikyan D., Durand G., Forey N., McKay-Chopin S., Robinot N., et al. Rare, evolutionarily unlikely missense substitutions in CHEK2 contribute to breast cancer susceptibility: results from a breast cancer family registry case-control mutation-screening study. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R6. doi: 10.1186/bcr2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casadei S., Norquist B.M., Walsh T., Stray S., Mandell J.B., Lee M.K., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A., King M.C. Contribution of inherited mutations in the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2 to familial breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2222–2229. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X., Dong X., Liu W., Chen J. Characterization of CHEK2 mutations in prostate cancer. Hum. Mutat. 2006;27:742–747. doi: 10.1002/humu.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nevanlinna H., Bartek J. The CHEK2 gene and inherited breast cancer susceptibility. Oncogene. 2006;25:5912–5919. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X., Georgieva B., Chabes A., Domkin V., Ippel J.H., Schleucher J., Wijmenga S., Thelander L., Rothstein R. Mutational and structural analyses of the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1 define its Rnr1 interaction domain whose inactivation allows suppression of mec1 and rad53 lethality. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:9076–9083. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9076-9083.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundin C., North M., Erixon K., Walters K., Jenssen D., Goldman A.S., Helleday T. Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) produces heat-labile DNA damage but no detectable in vivo DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3799–3811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaag A., Walsh T., Renbaum P., Kirchhoff T., Nafa K., Shiovitz S., Mandell J.B., Welcsh P., Lee M.K., Ellis N., et al. Functional and genomic approaches reveal an ancient CHEK2 allele associated with breast cancer in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:555–563. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falck J., Mailand N., Syljuasen R.G., Bartek J., Lukas J. The ATM-Chk2-Cdc25A checkpoint pathway guards against radioresistant DNA synthesis. Nature. 2001;410:842–847. doi: 10.1038/35071124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavtigian S.V., Greenblatt M.S., Lesueur F., Byrnes G.B. In silico analysis of missense substitutions using sequence-alignment based methods. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:1327–1336. doi: 10.1002/humu.20892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathe E., Olivier M., Kato S., Ishioka C., Hainaut P., Tavtigian S.V. Computational approaches for predicting the biological effect of p53 missense mutations: a comparison of three sequence analysis based methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1317–1325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adzhubei I.A., Schmidt S., Peshkin L., Ramensky V.E., Gerasimova A., Bork P., Kondrashov A.S., Sunyaev S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng P.C., Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan P.A., Duraisamy S., Miller P.J., Newell J.A., McBride C., Bond J.P., Raevaara T., Ollila S., Nystrom M., Grimm A.J., et al. Interpreting missense variants: comparing computational methods in human disease genes CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH2, MECP2, and tyrosinase (TYR) Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:683–693. doi: 10.1002/humu.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saslow D., Boetes C., Burke W., Harms S., Leach M.O., Lehman C.D., Morris E., Pisano E., Schnall M., Sener S., et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2007;57:75–89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoni L., Sodha N., Collins I., Garrett M.D. CHK2 kinase: cancer susceptibility and cancer therapy—two sides of the same coin? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:925–936. doi: 10.1038/nrc2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavtigian S.V., Byrnes G.B., Goldgar D.E., Thomas A. Classification of rare missense substitutions, using risk surfaces, with genetic- and molecular-epidemiology applications. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:1342–1354. doi: 10.1002/humu.20896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.